Effect of Community Nutrition Rehabilitation Using a Multi-Ingredient Flour on the Weight Growth of Moderately Acute Malnourished Children in Benin

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Framework and Design

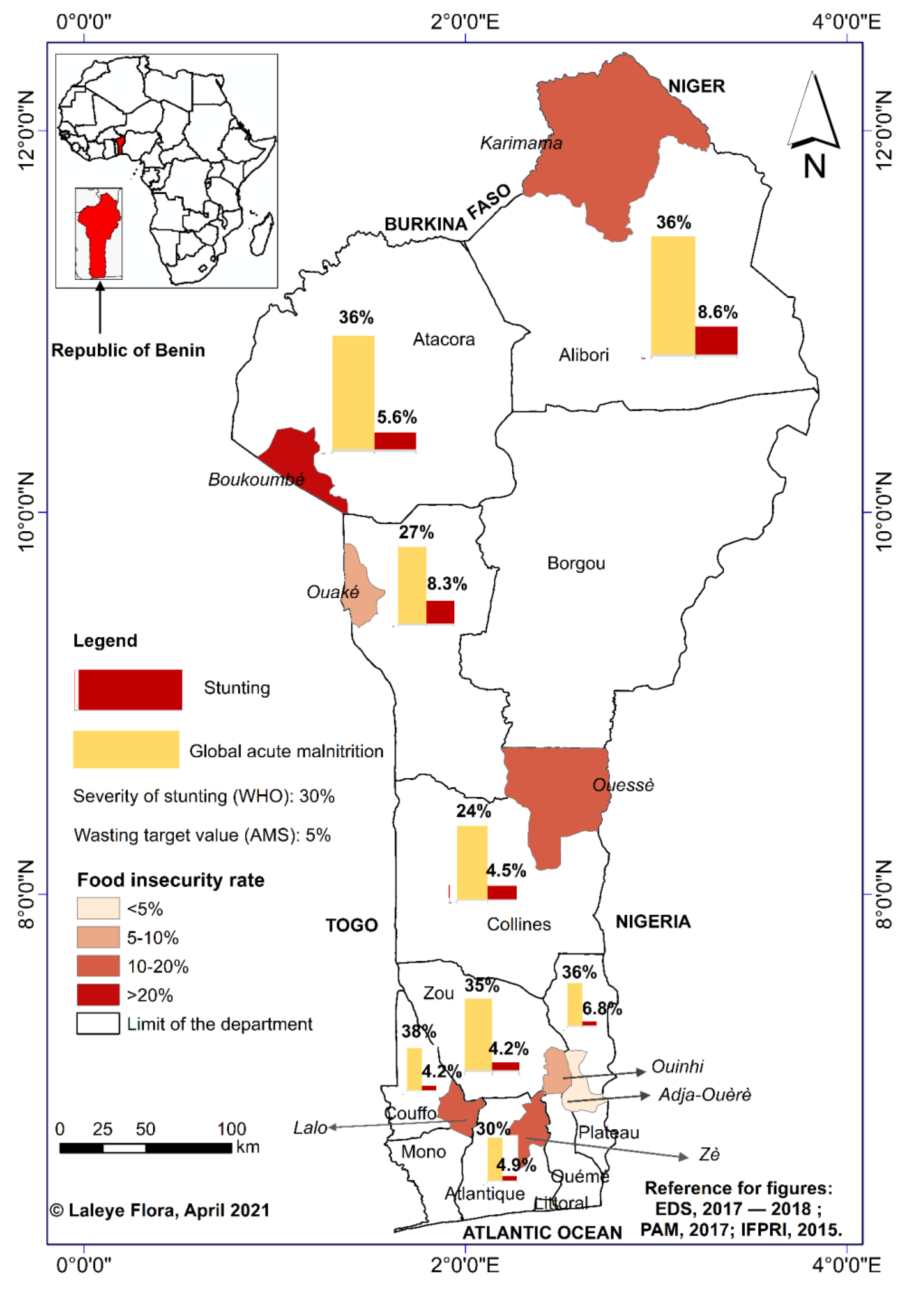

2.2. Study Area

2.3. Participants and Sampling

2.4. LNR Learning Sessions

2.5. Experimental Foods

2.6. FARIFORTI Flour Porridge

2.7. Other Complementary Foods

2.8. Sensory Test

2.9. Anthropometric Measurement and Food Consumption Data

2.10. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Children’s Characteristics

3.2. Acceptability of the FARIFORTI Flour

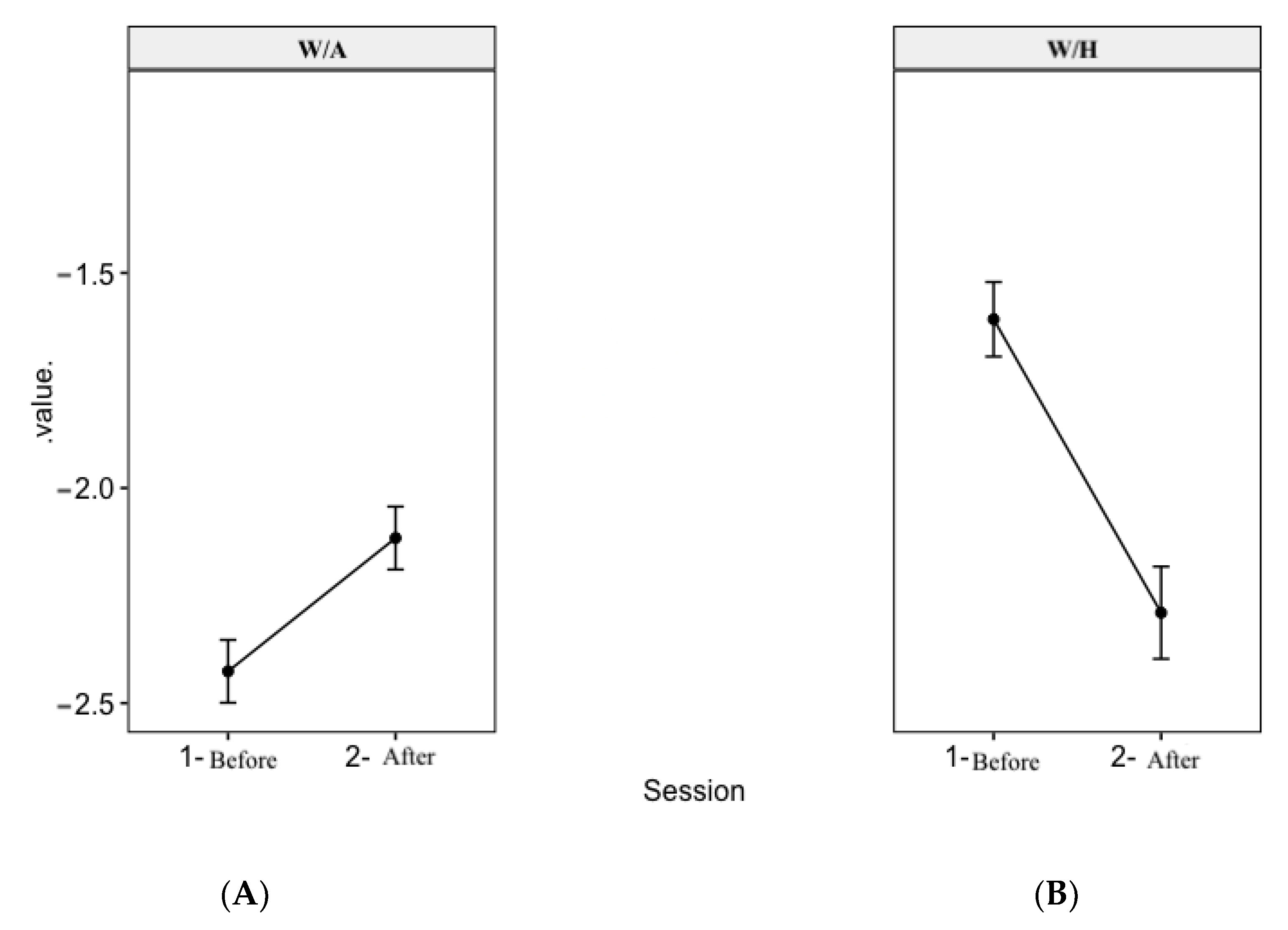

3.3. Anthropometric Indices before and after the LNR Sessions

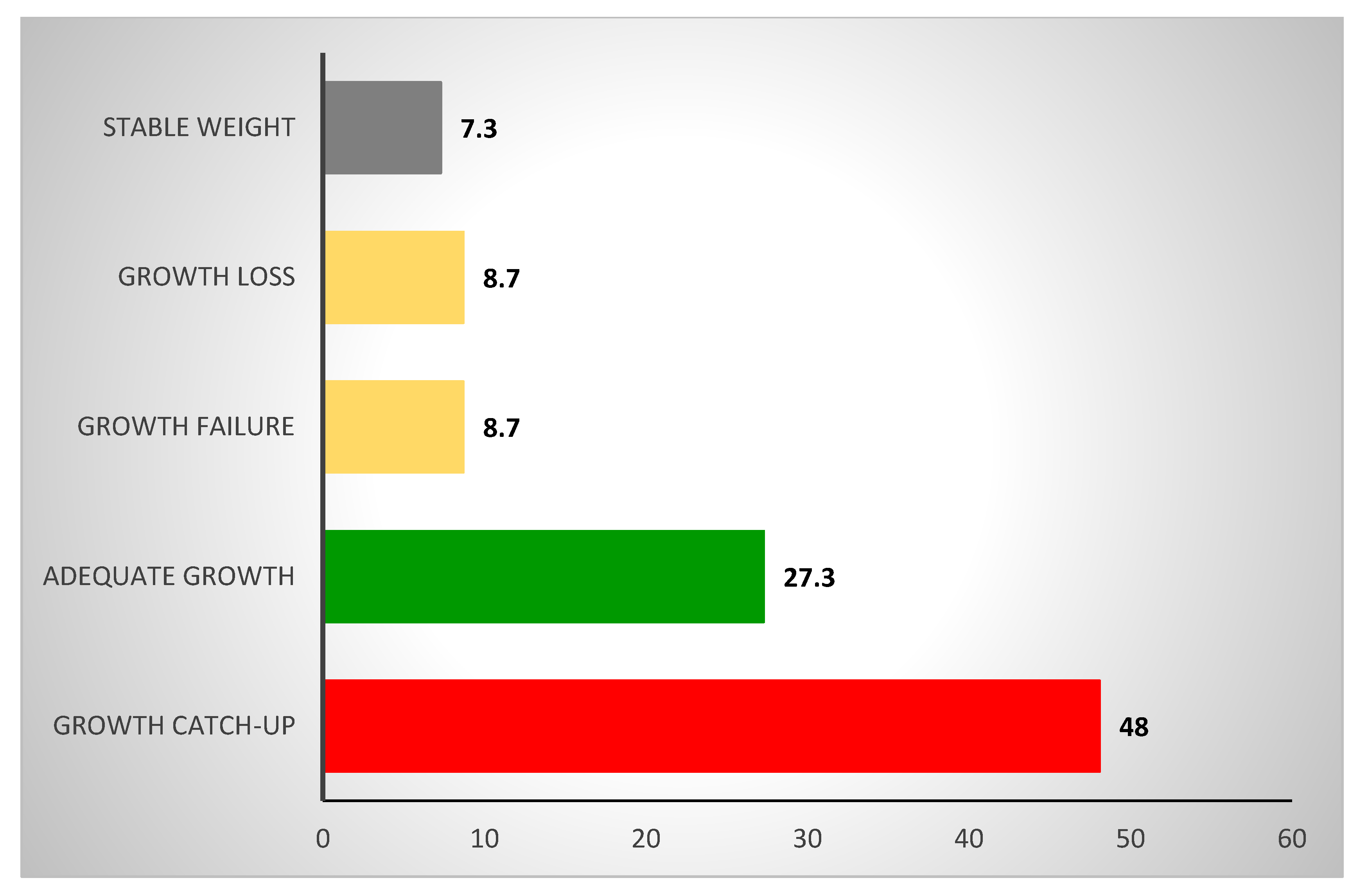

3.4. Weight Growth of Children after the LNR Experimental Sessions

3.5. Energy and Nutrient Intake from Foods Consumed during the LNR Sessions

4. Discussion

5. Limits

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- INSAE. Multi-indicators clusters surveys. In Final Report [Enquête par Grappes à Indicateurs Multiples. Rapport Final]; INSAF: Cotonou, Benin, 2014; p. 2014247. [Google Scholar]

- INSAE. Demographic and Health Survey 2017–2018 [Enquête Démographique et de Santé au Bénin 2017–2018: Indicateurs Clés]; INSAF: Cotonou, Benin, 2019; pp. 255–284. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Technical Note: Supplementary Foods for the Management of Moderate Acute Malnutrition in Infants and Children 6–59 Months of Age. 2012. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/75836 (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Teshome, G.B.; Whiting, S.J.; Green, T.J.; Mulualem, D.; Henry, C.J. Scaled-up nutrition education on pulse cereal complementary food practice in Ethiopia: A cluster-randomized trial. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Makame, J.; De Kock, H.; Emmambux, N.M. Nutrient density of common African indigenous/local complementary porridge samples. LWT Food Sci. Technol. 2020, 133, 109978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchini, M.; Rosi, A.; Giopp, F.; Lolli, V.; Scazzina, F.; Carini, E. The “Pappa di Parma” integrated approach against moderate acute malnutrition. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Technol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adetola, O.Y.; Onabanjo, O.O.; Stark, A.H. The search for sustainable solutions: Producing a sweet potato based complementary food rich in vitamin A, zinc and iron for infants in developing countries. Sci. Afr. 2020, 8, e00363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leng, M.S.; Tobit, P.; Demasse, A.M.; Wolf, K.; Gouado, I.; Ndjouenkeu, R.; Rawel, H.M.; Schweigert, F.J. Nutritional and anti-oxidant properties of yam (Dioscorea schimperiana) based complementary food formulation. Sci. Afr. 2019, 5, e00132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bodjrenou, F.S.; Amoussa Hounkpatin, W.; Houndji, S.; Lokonon, J.; Kodjo, M.A.; Dossa, L.A. Une étude pilote en milieu rural au sud-bénin pour la réduction de la malnutrition chronique par une approche alimentaire. Ann. Sci. Agron. 2018, 22, 115–132. [Google Scholar]

- Fanou-Fogny, N.; Chadare, F.J.; Madode, Y.E.; Kanhounon, S.M.; Houndélo, G.; Yétongnon, K.; Kayode, A.P.P.; Hounhouigan, D.J. Technical Note No1. Free-Listing Method: Applications for Inflant Flours in Benin. Technical Note Series on Food Ethnography [Fiche Technique N°1. La Méthode Free-listing: Applications Pour les Farines Infantiles au Bénin. Fiches Techniques sur l’ethnographie Alimentaire]; Benin National Library Publications: Cotonou, Benin, 2017; 54p. [Google Scholar]

- Nago, M.; Yemoa, A.; Mizehoun-Adissoda, C.; Bigot, A.; Hounhouigan, J. Evaluation de la qualité nutritionnelle des farines infantiles fabriquées et vendues au Benin. J. So. B. Cl. Bénin 2018, 29, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. Complementary Feeding of Young Children in Developing Countries: A Review of Current Scientific Knowledge; WHO/NUT /98.1; World Health Organization: Geneva, Swizterland, 1998.

- Nagahori, C.; Kinjo, Y.; Vodounon, A.J.; Alao, M.J.; Batossi, G.P.; Hounkpatin, B.; Houenassi, E.A.; Yamauchi, T. Possible effect of maternal safe food preparation behavior on child malnutrition in Benin, Africa. Pediatr. Int. 2018, 60, 875–881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojuri, O.T.; Ezekiel, C.N.; Sulyok, M.; Ezeokolic, O.T.; Oyedele, O.A.; Ayeni, K.I.; Eskola, M.K.; Šarkanj, B.; Hajšlová, J.; Adeleke, R.A.; et al. Assessing the mycotoxicological risk from consumption of complementary foods by infants and young children in Nigeria. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2018, 121, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- F&BKP. ARF Projects Are Funded by the NWO-WOTRO Science for Global Development Funding Instrument Food & Business Research (FBR) Factsheet Final Research Findings ARF-1Factsheet Final Findings Applied Research Fund Call 1 Agro Ecological Food Resources for Healthy Infant Nutrition in Benin (INFLOR). Actsheet Final Findings Applied Research Fund Call 1. Available online: https://knowledge4food.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/arf1-3g_benin-inflor_final-factsheet_nw.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2021).

- Kêdoté, N.M.; Fassinou, E.; Sopoh, G.; Capo-chichi, J.; Darboux, A. Evaluation de la prise en charge des enfants dénutris au niveau communautaire dans la commune de Lalo, Bénin. JAPGM 2018, 5, 28–32. [Google Scholar]

- CORE-Group. Déviance Positive/Foyer: Manuel Ressource pour une Réhabilitation Durable des Enfants Malnutris. Available online: https://www.fsnnetwork.org/resource/deviance-positive-manuel-ressource-pour-une-rehabilitation-durable-des-enfants-malnutrits (accessed on 10 September 2017).

- Salissou, M.M.; Maazou, B.A.; Seini, S.H. Essai d’une farine de sevrage dans la rehabilitation nutritionnelle de la malnutrition aigüe en milieu communautaire, au Niger. J. Appl. Biosci. 2020, 151, 15573–15583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millimono, T.M.; Toure, F.; Diallo, A.S.; Bamba, I.F. Evaluation de la prise en charge des enfants malnutris aigus modérés de 6 à 59 mois dans les Foyers d’Apprentissage et de Réhabilitation Nutritionnelle de la préfecture de Kouroussa. Nutr. Santé 2019, 8, 42–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wellek, S.; Blettner, M. Establishing Equivalence or Non-Inferiority in Clinical Trials: Part 20 of a Series on Evaluation of Scientific Publications. Dtsch. Arztebl. Int. 2012, 109, 674–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- PAM. Examen Stratégique National « Faim Zéro » au Benin à l’horizon 2030. Rapport final. 2018. 181p. Available online: https://reliefweb.int/report/benin/examen-strat-gique-national-faim-z-ro-au-benin (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- IFPRI. Global Hunger Index: Getting to Zero Hunger. USA/Washington, DC/Dublin/Bonn. 2016. Available online: https://www.ifpri.org/publication/2016-global-hunger-index-getting-zero-hunger (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Buchner, A.; Lang, A.G. Statistical power analyses using G*Power 3.1: Tests for correlation and regression analyses. Behav. Res. Methods 2009, 41, 1149–1160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fanou-Fogny, N.; Fadonougbo, F.; Gbodja, R.; Dohou, G.; Nonfon, I.; Mongbo, R.L. Technical note: Guidance for community management of moderately acute malnourished children. In Fiche Technique: Guide Pour la Prise en Charge Communautaire des Enfants Malnutris Aigus Modérés au Bénin; Benin National Library Publications: Cotonou, Benin, 2017; 40p, ISBN 978-99919-82-65-6. Available online: https://can-benin.bj/Rapport_Etude_Evaluation/EvalFarn-guide%20FARN%20051216.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2021).

- Chadare, F.J.; Madode, Y.E.; Fanou-Fogny, N.; Kindossi, J.M.; Ayosso, J.O.; Honfo, S.H.; Hounhouigan, D.J. Indigenous food ingredients for complementary food formulations to combat infant malnutrition in Benin: A review. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2018, 98, 439–455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madrelle, J.; Lange, C.; Boutrolle, I.; Valade, O.; Weenen, H.; Monnery-Patris, S.; Nicklaus, S. Development of a new in-home testing method to assess infant food liking. Appetite 2017, 113, 274–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popper, R.; Kroll, J.J. Conducting sensory research with children. J. Sens. Stud. 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OMS. Normes de Croissance de l’enfant: World Health Organization/Nutrition for Health and Development (NHD)/Sustainable Development and Healthy Environments; Organisation Mondiale de la Santé: Washington, DC, USA, 2006; p. 6.

- Vincent, A.; Grande, F.; Compaoré, E.; Amponsah Annor, G.; Addy, P.A.; Aburime, L.C.; Ahmed, D.; Bih Loh, A.M.; Dahdouh Cabia, S.; Deflache, N.; et al. FAO/INFOODS Food Composition Table for Western Africa (2019) User Guide & Condensed Food Composition Table/Table de Composition des Aliments FAO/INFOODS Pour l’Afrique de l’Ouest (2019) Guide d’utilisation & Table de Composition des Aliments Condensée; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Borg, B.; Sok, D.; Mihrshahi, S.; Griffin, M.; Chamnan, C.; Berger, J.; Laillou, A.; Roos, N.; Wieringa, F.T. Effectiveness of a locally produced ready-to-use supplementary food in preventing growth faltering for children under 2 years in Cambodia: A cluster randomised controlled trial. Matern. Child Nutr. 2020, 16, e12896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, F.; Esmaillzadeh, A.; Alipoor, E.; Moslemi, M.; Yaseri, M.; Hosseinzadeh-Attar, M.J. Effect of a newly developed ready-to-use supplementary food on growth indicators in children with mild to moderate malnutrition. Public Health 2020, 185, 290e297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, M.J.; Ryan, N.K.; Tandon, R.; Mathur, M.; Girma, T.; Steiner-Asiedu, M.; Saalia, F.; Zaidi, S.; Soofi, S.; Okos, M.; et al. Acceptability of locally produced ready-to-use therapeutic foods in Ethiopia, Ghana, Pakistan and India. Matern. Child Nutr. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsido, S.F.; Hordofa, A.A.; Ayelign, A.; Belachew, T.; Hensel, O. Effects of fermentation and malt addition on the physicochemical properties of cereal based complementary foods in Ethiopia. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Regions | Commune | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | ||

| South | Adja-Ouèrè | 31 | 10.7 |

| Lalo | 32 | 11.1 | |

| Zè | 30 | 10.4 | |

| Total Southern Benin | 93 | 32.2 | |

| Center | Ouèssè | 24 | 8.3 |

| Ouinhi | 30 | 10.4 | |

| Total Central Benin | 54 | 18.7 | |

| North | Boukoumbé | 41 | 14.2 |

| Karimama | 53 | 18.3 | |

| Ouaké | 48 | 16.6 | |

| Total Northern Benin | 142 | 49.1 | |

| Total | 289 | 100 | |

| Characteristics | Total (n = 289) | Girls (n = 167) | Boys (n = 122) | p-Value * |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex (%) | 57.8 | 42.2 | 0.974 a | |

| age (months) | 0.774 b | |||

| Average (SE) | 24.63 (0.80) | 25.11 (1.11) | 23.97 (1.14) | |

| 95% CI | (23.05, 26.20) | (22.92, 27.30) | (21.71, 26.22) | |

| age class (%) | 0.944 a | |||

| (6–24) | 166 (57.4%) | 95 (56.9%) | 71 (58.2%) | |

| (24–36) | 61 (21.1%) | 35 (21.0%) | 26 (21.3%) | |

| (36–60) | 62 (21.5%) | 37 (22.2%) | 25 (20.5%) | |

| weight (kg) | 0.379 b | |||

| Mean (SE) | 8.78 (0.13) | 8.70 (0.18) | 8.89 (0.18) | |

| 95% CI | (8.53, 9.03) | (8.35, 9.06) | (8.53, 9.24) | |

| height (cm) | 0.958 b | |||

| Mean (SE) | 78.22 (0.54) | 78.35 (0.75) | 78.04 (0.77) | |

| 95% CI | (77.16, 79.28) | (76.87, 79.83) | (76.52, 79.56) | |

| MUAC (cm) | 0.893 b | |||

| Average (SE) | 29.11 (2.33) | 29.70 (3.13) | 28.31 (3.49) | |

| 95% CI | (24.53, 33.69) | (23.52, 35.88) | (21.41, 35.21) | |

| weight-for-height | 0.031 b | |||

| Average (SE) | −1.61 (0.09) | −1.53 (0.13) | −1.71 (0.11) | |

| 95% CI | (−1.78, −1.44) | (−1.78, −1.28) | (−1.93, −1.50) | |

| height-for-age | 0.009 b | |||

| Average (SE) | −2.32 (0.11) | −2.11 (0.14) | −2.61 (0.17) | |

| 95% CI | (−2.53, −2.11) | (−2.38, -1.84) | (−2.94, −2.28) | |

| weight-for-age | 0.001 b | |||

| Average (SE) | −2.43 (0.07) | −2.29 (0.10) | −2.61 (0.10) | |

| 95% CI | (−2.57, −2.28) | (−2.50, −2.09) | (−2.80, −2.41) |

| Foods Without FARIFORTI | Foods With FARIFORTI | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy (kJ) | <0.001 | ||

| Mean (SE) | 11,004.33 (414.20) | 20,105.26 (599.28) | |

| 95% CI | (10,189.13–11,819.53) | (18,925.74–21,284.78) | |

| Protein (g) | <0.001 | ||

| Mean (SE) | 134.80 (48.44) | 193.15 (49.10) | |

| 95% CI | (39.47–230.14) | (96.50–289.80) | |

| Fat (g) | <0.001 | ||

| Mean (SE) | 134.82 (45.77) | 175.14 (46.43) | |

| 95% CI | (44.73–224.91) | (83.77–266.52) | |

| Carbohydrates (g) | <0.001 | ||

| Mean (SE) | 375.05 (47.46) | 507.31 (48.29) | |

| 95% CI | (281.65–468.45) | (412.25–602.36) | |

| Iron (mg) | <0.001 | ||

| Mean (SE) | 197.61 (56.67) | 225.24 (57.33) | |

| 95% CI | (86.07–309.14) | (112.40–338.08) | |

| Vitamin A (µg) | 0.958 | ||

| Mean (SE) | 1378.90 (91.12) | 1378.93 (92.38) | |

| 95% CI | (1199.60–1558.26) | (1197.07–1560.74) | |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 0.409 | ||

| Mean (SE) | 125.93 (12.16) | 135.63 (13.45) | |

| 95% CI | (102.00–149.87) | (109.16–162.09) |

| No. of Children without Weight Gain (n = 46) | No. of Children Weight Gain (n = 243) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| FARIFORTI Porridge | |||

| Energy (kJ) | 0.823 | ||

| Mean (SE) | 10,231.46 (1470.56) | 8816.43 (442.02) | |

| 95% CI | (7269.59, 13,193.32) | (7945.73, 9687.12) | |

| Carbohydrates (g) | 0.017 | ||

| Mean (SE) | 124.03 (5.46) | 131.56 (2.05) | |

| 95% CI | (113.04, 135.03) | (127.53, 135.60) | |

| Iron (mg) | 0.042 | ||

| Mean (SE) | 19.09 (2.99) | 26.25 (1.37) | |

| 95% CI | (13.07, 25.11) | (23.55, 28.95) | |

| Other foods | |||

| Energy (kJ) | 0.855 | ||

| Mean (SE) | 10,940.88 (944.38) | 11,086.83 (465.48) | |

| 95% CI | (9038.81, 12,842.96) | (10,169.93, 12,003.74) | |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 0.030 | ||

| Mean (SE) | 71.96 (16.66) | 136.82 (14.23) | |

| 95% CI | (38.41, 105.51) | (108.79, 164.85) | |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Lalèyè, F.T.F.; Fanou-Fogny, N.; Chadare, F.J.; Madodé, Y.E.; Kayodé, P.A.P.; Hounhouigan, D.J. Effect of Community Nutrition Rehabilitation Using a Multi-Ingredient Flour on the Weight Growth of Moderately Acute Malnourished Children in Benin. Foods 2023, 12, 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12020263

Lalèyè FTF, Fanou-Fogny N, Chadare FJ, Madodé YE, Kayodé PAP, Hounhouigan DJ. Effect of Community Nutrition Rehabilitation Using a Multi-Ingredient Flour on the Weight Growth of Moderately Acute Malnourished Children in Benin. Foods. 2023; 12(2):263. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12020263

Chicago/Turabian StyleLalèyè, Flora T. F., Nadia Fanou-Fogny, Flora J. Chadare, Yann E. Madodé, Polycarpe A. P. Kayodé, and Djidjoho J. Hounhouigan. 2023. "Effect of Community Nutrition Rehabilitation Using a Multi-Ingredient Flour on the Weight Growth of Moderately Acute Malnourished Children in Benin" Foods 12, no. 2: 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12020263

APA StyleLalèyè, F. T. F., Fanou-Fogny, N., Chadare, F. J., Madodé, Y. E., Kayodé, P. A. P., & Hounhouigan, D. J. (2023). Effect of Community Nutrition Rehabilitation Using a Multi-Ingredient Flour on the Weight Growth of Moderately Acute Malnourished Children in Benin. Foods, 12(2), 263. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12020263