Consumer Nutritional Awareness, Sustainability Knowledge, and Purchase Intention of Environmentally Friendly Cookies in Croatia, France, and North Macedonia

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Study Population

2.2. Nutritional Awareness Index and Sustainability Knowledge Score

2.3. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

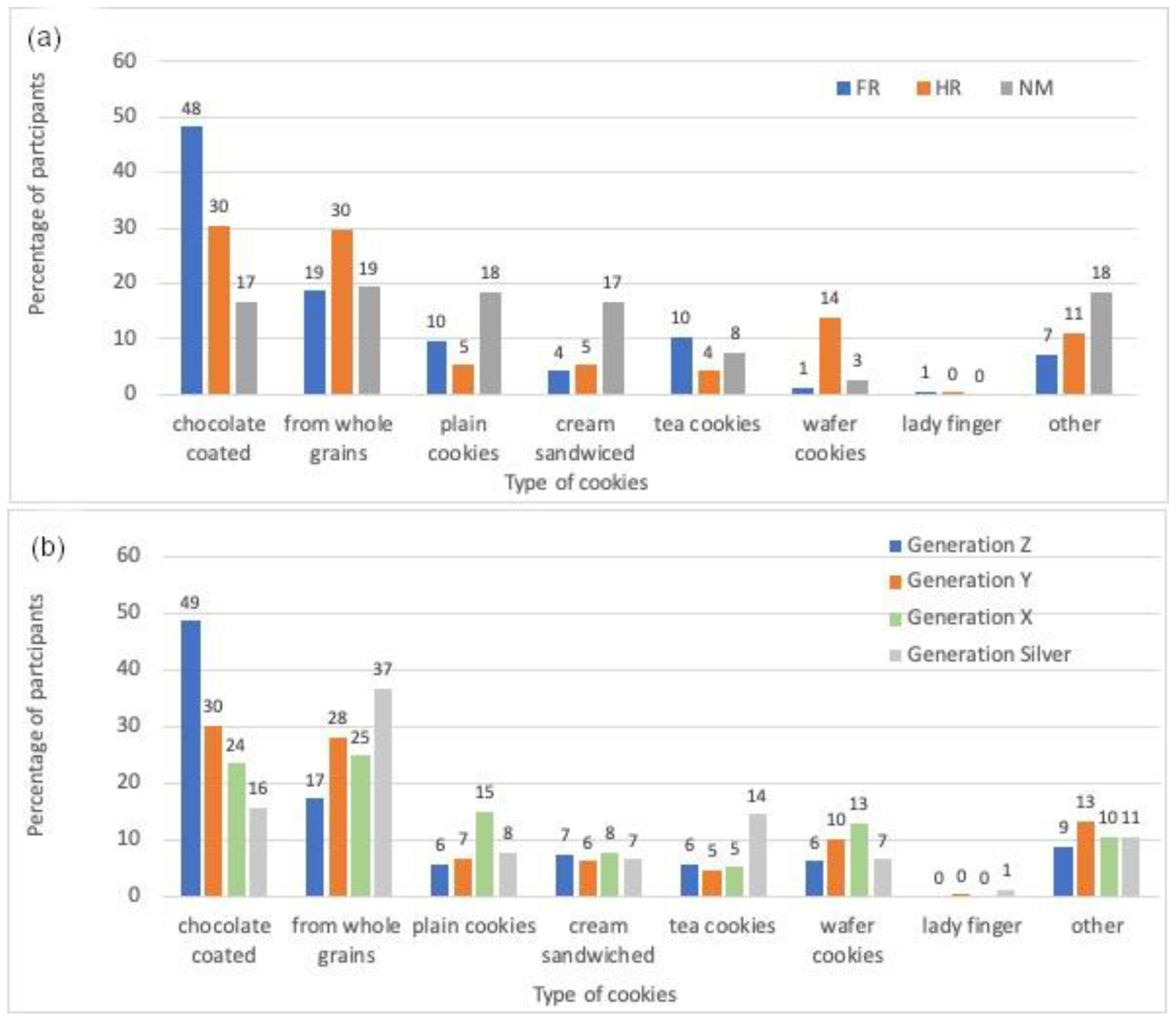

3.1. Cookie Consumption and Preference Choice

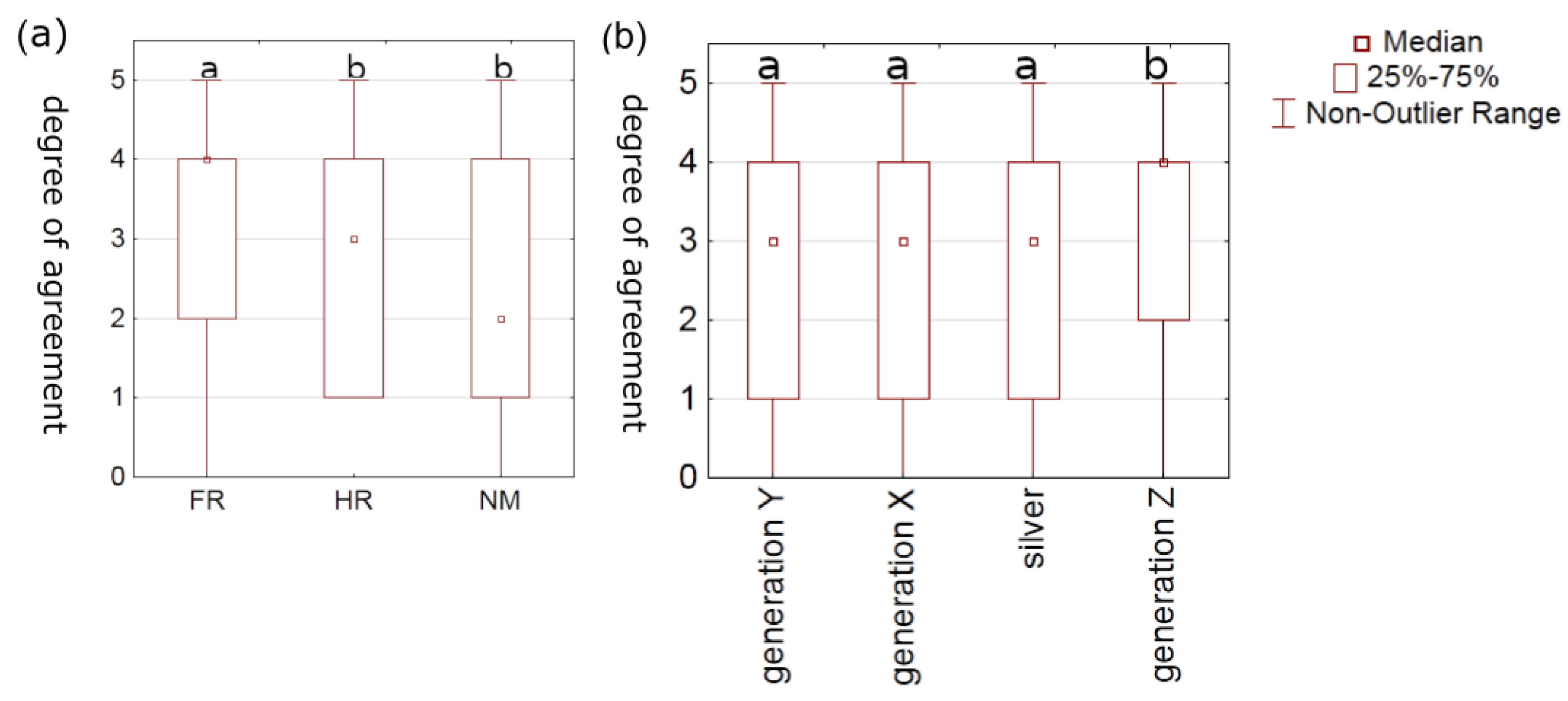

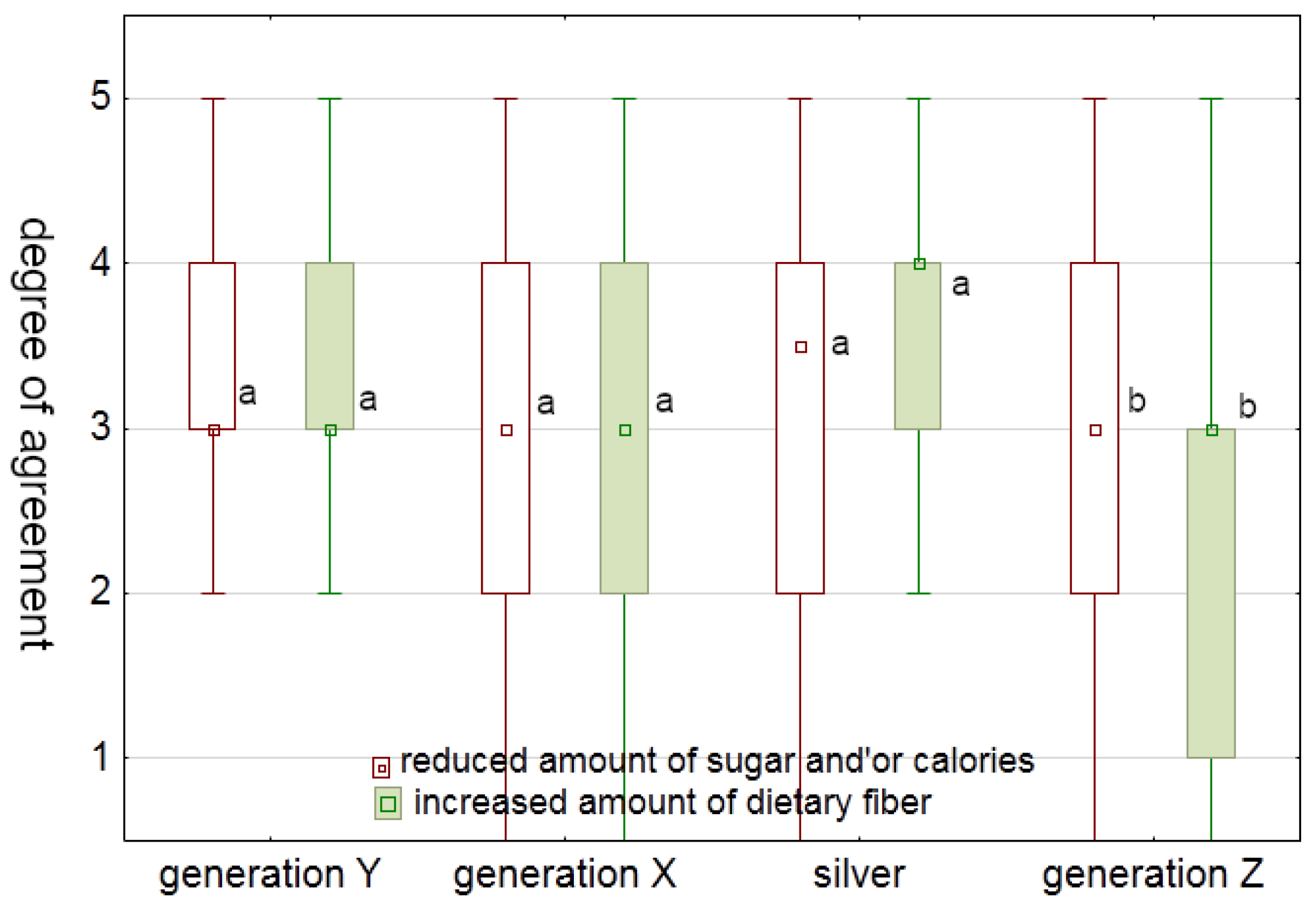

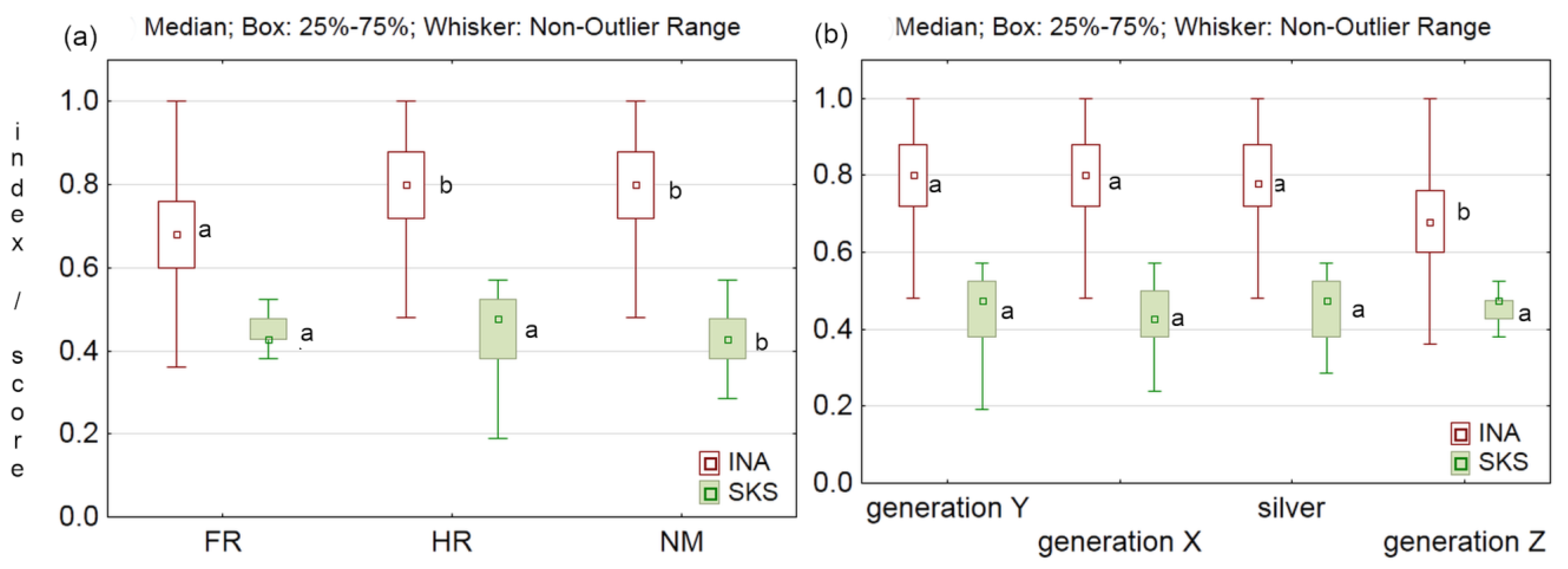

3.2. Nutritional Awareness and Interest in Health and Nutritional Value of Cookies

3.3. Sustainability Knowledge Score (SKS)

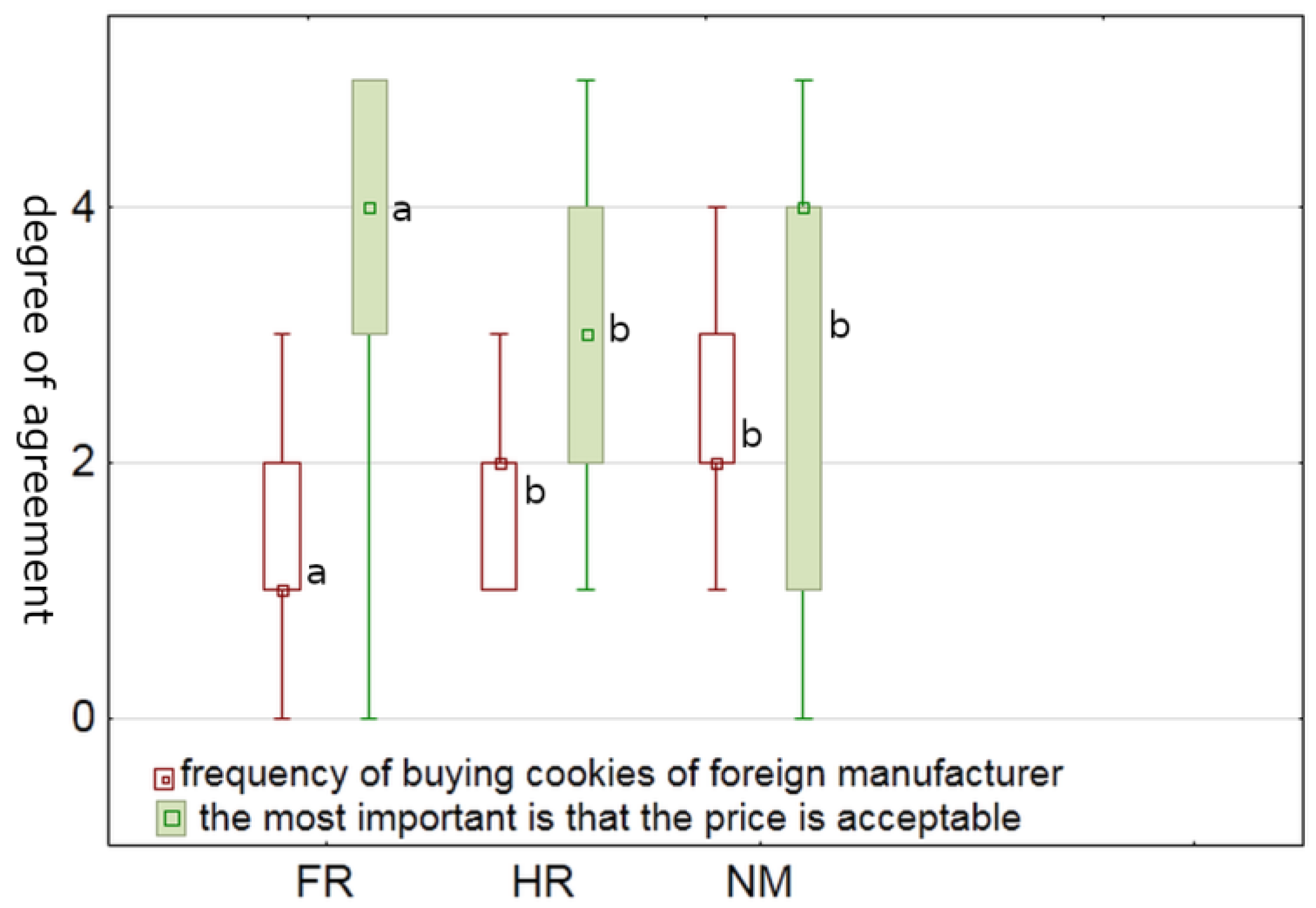

3.4. Purchase Intention

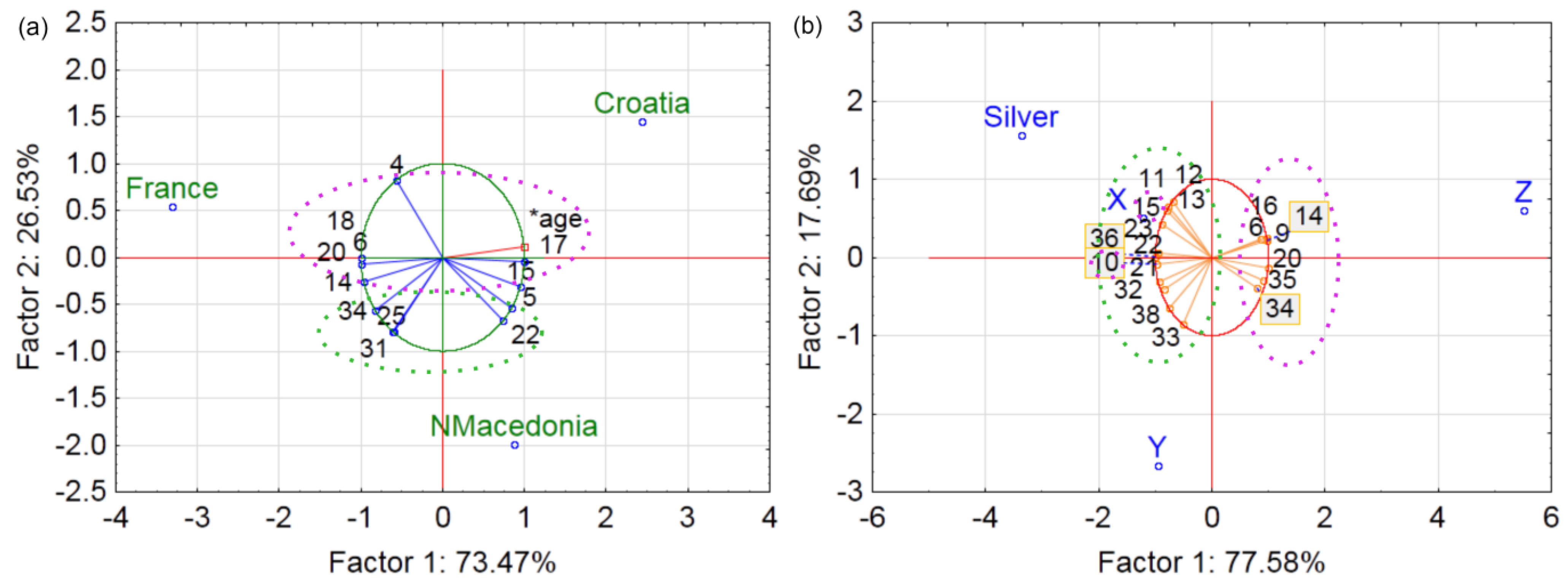

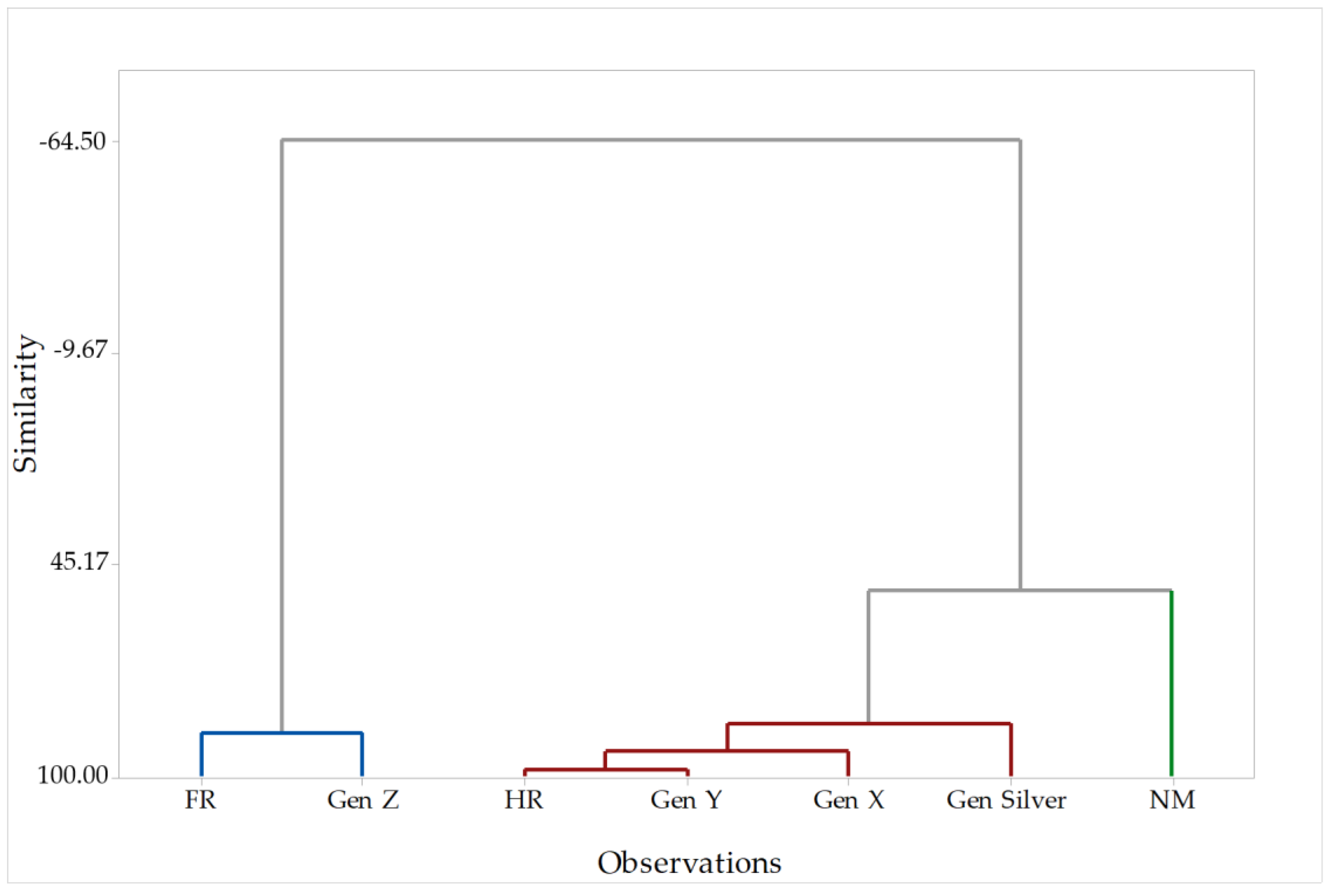

3.5. Principal Components and Clusters

3.6. Limitations of Study

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sajdakowska, M.; Jankowski, P.; Gutkowska, K.; Guzek, D.; Żakowska-Biemans, S.; Ozimek, I. Consumer acceptance of innovations in food: A survey among Polish consumers. J. Consum. Behav. 2018, 17, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrescu, D.C.; Vermeir, I.; Petrescu-Mag, R.M. Consumer understanding of food quality, healthiness, and environmental impact: A cross-national perspective. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagchi, D. Nutraceutical and Functional Food Regulations in the United States and around the World, 3rd ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Galanakis, C.M. The food systems in the era of the coronavirus (COVID-19) pandemic crisis. Foods 2020, 9, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil, A.; Ortega, R.M.; Maldonado, J. Wholegrain cereals and bread: A duet of the Mediterranean diet for the prevention of chronic diseases. Public Health Nutr. 2011, 14, 2316–2322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kantike, I.; Eglite, A. Consumer behaviour in the market of wholegrain products. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference, Jelgava, Latvia, 26–27 April 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Florence, S.P.; Asna, U.; Asha, M.R.; Jyotona, R. Sensory, physical and nutritional qualities of cookies prepared from pearl millet (Opennisetum typhoideum). Food Process. Technol. 2014, 5, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadam, S.U.; Prabhasankar, P. Marine foods as functional ingredients in bakery and pasta products. Food Res. Int. 2010, 43, 1975–1980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atlantic Area Healthy Food Eco-System (AHFES). Available online: https://www.ahfesproject.com/services/consumer-and-market-trends-reports/ (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Canalis, M.S.B.; Leon, A.E.; Ribotta, P.D. Effect of inulin on dough and biscuit quality produced from different flours. Int. J. Food Stud. 2017, 6, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, A.; Kumar, P. Gluten free approach in fat and sugar amended biscuits: A healthy concern for obese and diabetic individuals. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2017, 42, e13546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, D.; Gabaj, N.N.; Vujić, L.; Ščetar, M.; Krisch, J.; Miler, M.; Štefanović, M.; Novotni, D. Application of fruit by-products and edible film to cookies: Antioxidant activity and concentration of oxidized LDL receptor in women—A first approach. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kekalih, A.; Sagung, I.O.A.A.; Fahmida, U.; Ermayani, E.; Mansyur, M. A multicentre randomized controlled trial of food supplement intervention for wasting children in Indonesia-study protocol. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buffière, C.; Hiolle, M.; Peyron, M.A.; Richard, R.; Meunier, N.; Batisse, C.; Rémond, D.; Dupont, D.; Nau, F.; Pereira, B.; et al. Food matrix structure (from biscuit to custard) has an impact on folate bioavailability in healthy volunteers. Eur. J. Nutr. 2020, 60, 411–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puerta, P.; Laguna, L.; Tárrega, A.; Carrillo, E. Relevant elements on biscuits purchasing decision for coeliac children and their parents in a supermarket context. Food Qual. Prefer. 2022, 98, 104496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sörqvist, P.; Haga, A.; Holmgren, M.; Hansla, A. An eco-label effect in the built environment: Performance And comfort effects of labeling a light source environmentally friendly. J. Environ. Psychol. 2015, 42, 123–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbasi, R.; Martinez, P.; Ahmad, R. An ontology model to represent aquaponics 4, 0 system’s knowledge. Inf. Process. Agric. 2021, 9, 514–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hemathilake, D.M.K.S.; Gunathilake, D.M.C.C. High-productive agricultural technologies to fulfill future food demands: Hydroponics, aquaponics, and precision/smart agriculture. In Future Foods: Global Trends, Opportunities, and Sustainability Challenges; Bhat, R., Ed.; Academic Press: London, UK, 2022; pp. 555–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grasso, S.; Asioli, D. Consumer preferences for upcycled ingredients: A case study with biscuits. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 84, 103951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, E.; Kahveci, D. Consumers’ purchase intention for upcycled foods: Insights from Turkey. Future Foods 2022, 6, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, T.C.G.; Caleja, C.; Oliveira, M.B.P.P.; Pereira, E.; Barros, L. Reuse of fruits and vegetables biowaste for sustainable development of natural ingredients. Food Biosci. 2023, 53, 102711. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, D.; Novotni, D.; Krisch, J.; Bosiljkov, T.; Ščetar, M. The optimisation of cookie formulation with grape and aronia pomace powders as cocoa substitutes. Croat. J. Food Technol. Biotechnol. Nutr. 2020, 15, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurendić, T.; Ščetar, M. Aronia melanocarpa products and byproducts for health and nutrition: A review. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molnar, D.; Novotni, D.; Kurek, M.; Galić, K.; Iveković, D.; Bionda, H.; Ščetar, M. Characteristics of edible films enriched with fruit by-products and their application on cookies. Food Hydrocoll. 2023, 135, 108191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukboonyasatit, D. Prediction of Peoples’ Intentions and Actual Consumption of Functional Foods in Palmerston North. Ph.D. Thesis, Massey University Palmerston North, Auckland, New Zealand, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Nystrand, B.T.; Olsen, S.O. Consumers’ attitudes and intentions toward consuming functional foods in Norway. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 80, 103827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sielicka-Różyńska, M.; Jerzyk, E.; GluzaInt, N. Consumer perception of packaging: An eye-tracking study of gluten-free cookies. J. Consum. Stud. 2021, 45, 14–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dean, M.; Shepherd, R.; Arvola, A.; Vassallo, M.; Winkelmann, M.; Claupein, E.; Lähteenmäki, L.; Raats, M.M.; Saba, A. Consumer perceptions of healthy cereal products and production methods. J. Cereal Sci. 2007, 46, 188–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, A. Development of functional food with the participation of the consumer. Motivators for consumption of functional products. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2015, 39, 2–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miklavec, K.; Pravst, I.; Grunert, K.G.; Klopcic, M.; Pohar, J. The influence of health claims and nutritional composition on consumers’ yoghurt preferences. Food Qual. Prefer. 2015, 43, 26–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puerta, P.; Carrillo, E.; Badia-Olmos, C.; Laguna, L.; Rosell, C.M.; Tárrega, A. Coeliac consumers’ expectations and eye fixations on commercial gluten-free bread packages. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2022, 163, 113622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Šedík, P.; Hudecová, M.; Predanócyová, K. Exploring consumers’ preferences and attitudes to honey: Generation approach in Slovakia. Foods. 2023, 12, 1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Čukelj, N.; Putnik, P.; Novotni, D.; Ajredini, S.; Voučko, B.; Ćurić, D. Market potential of lignans and omega-3 functional cookies. Brit. Food J. 2016, 118, 2420–2433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savelli, E.; Murmura, F. The intention to consume healthy food among older Gen-Z: Examining antecedents and mediators. Food Qual. Prefer. 2023, 105, 104788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narchi, I.; Walrand, S.; Boirie, Y.; Rousset, S. Emotions generated by food in elderly French people. J. Nutr. Health Aging. 2008, 12, 626–633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavolacci, M.P.; Déchelotte, P.; Ladner, J. Eating disorders among college students in France: Characteristics, help-and care-seeking. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 5914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Priporas, C.V.; Vellore-Nagarajan, D.; Kamenidou, I. Stressful eating indulgence by generation Z: A cognitive conceptual framework of new age consumers’ obesity. Eur. J. Mark. 2022, 56, 2978–3006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaylor, S.K.; Allen, I.; Crim, A.D.; Callihan, M.L. Calories and control: Eating habits, behaviors, and motivations of Generation Z females. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 25, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Durukan, A.; Gül, A. Mindful eating: Differences of generations and relationship of mindful eating with BMI. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2019, 18, 100172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitoayu, L.; Purwara Dewanti, L.; Melani, V.; Azahra Sumitra, P.; Rulina Marpaung, M. Differences in eating habits, stress, and weight changes among indonesian generations Y and Z students during the COVID-19 pandemic. J. Res. Health 2023, 13, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lairon, D.; Bertrais, S.; Vincent, S.; Arnault, N.; Galan, P.; Boutron, M.C.; Hercberg, S. Dietary fibre intake and clinical indices in the French Supplementation en Vitamines et Minéraux AntioXydants (SU.VI.MAX) adult cohort. Proc. Nutr. Soc. 2003, 62, 11–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Everything Guide to Generation Z. Available online: https://The%20everything%20guide%20to%20gen%20z/the-everything-guide-to-gen-z.pdf (accessed on 18 August 2023).

- Su, C.H.; Tsai, C.H.; Chen, M.H.; Lv, W.Q. US sustainable food market generation Z consumer segments. Sustainability 2019, 11, 3607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso, A.; O’Neill, M.A. Consumption of muscadine grape by-products: An exploration among Southern US consumers. Br. Food J. 2012, 114, 400–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cattaneo, C.; Lavelli, V.; Proserpio, C.; Laureati, M.; Pagliarini, E. Consumers’ attitude towards food by-products: The influence of food technology neophobia, education and information. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 54, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, S.; Ardoin, R.; Prinyawiwatkul, W. Factors Influencing Consumers’ Willingness-to-Try Seafood Byproducts. Foods 2023, 12, 1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrett, E.M.; Foster, S.I.; Beck, E.J. Whole grain and high-fibre grain foods: How do knowledge, perceptions and attitudes affect food choice? Appetite 2020, 149, 104630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Consumer Expectations for Brands in France for 2021. Available online: https://www.statista.com/statistics/1194944/consumer-expectations-brands-france/ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- FocusEconomics—France Archives. Available online: https://www.focus-economics.com/countries/france/ (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Cette, G.; Corde, S.; Lecat, R. Stagnation of productivity in France: A legacy of the crisis or a structural slowdown? Econ. Stat. 2017, 494–496, 11–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Bank Open Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 1 August 2023).

- Kusumawardhany, P.A. Frugal lifestyle trend among generation Z. In Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium on Management (INSYMA 2022), Bali, Indonesia, 19–20 May 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Liew, J.Y.; Ng, K.H.; Aziz, N.S.B.A. Antecedents of junk food purchase intention among generation Z: A case study of Kota Bharu, Kelantan. AIP Conf. Proc. 2023, 2500, 020042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coderoni, S.; Perito, M.A. Sustainable Consumption in the Circular Economy. An Analysis of Consumers’ Purchase Intentions for Waste-to-Value. Food. J. Clean. Prod. 2020, 252, 119870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- République Française. Available online: https://www.strategie.gouv.fr/english-articles?page=1 (accessed on 21 October 2023).

- IPSOS—Global Market Research and Public Opinion Specialist. Available online: https://www.ipsos.com/en-hr (accessed on 21 October 2023).

| Sociodemographic Characteristic | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall (n = 757) | Croatia (n = 472) | France (n = 166) | North Macedonia (n = 119) | |

| Gender 1, n (%) | ||||

| Female | 621 (82) | 389 (82) | 133 (80) | 99 (83) |

| Male | 135 (18) | 83 (18) | 32 (19.3) | 20 (17) |

| Age cohorts, n (%) | ||||

| Generation Z | 191 (25) | 58 (12) | 116 (70) | 17 (14) |

| Generation Y | 337 (45) | 278 (59) | 17 (10) | 42 (35) |

| Generation X | 153 (20) | 88 (19) | 20 (12) | 45 (38) |

| Generation Silver | 76 (10) | 48 (10) | 13 (8) | 15 (13) |

| Highest education qualification, n (%) | ||||

| Primary school | 4 (0.5) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.6) | / |

| Secondary school | 87 (11.5) | 74 (16) | 6 (3.6) | 7 (6) |

| Bachelor’s or master’s | 497 (66) | 276 (58.4) | 109 (65.8) | 112 (94) |

| PhD | 169 (22) | 119 (25) | 50 (30) | / |

| Employment status, n (%) | ||||

| Employed, full- or parttime | 503 (66.4) | 381 (81) | 20 (12) | 102 (86) |

| Student | 154 (20.3) | 30 (6.4) | 114 (69) | 10 (8) |

| Entrepreneur | 30 (4) | 30 (6.4) | / | / |

| Retired | 10 (1.3) | 5 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 2 (2) |

| Other | 60 (8) | 24 (5.1) | 31 (18.4) | 5 (4) |

| Index of Nutrition Awareness | Component |

|---|---|

| Do you introduce biologically active compounds into your body daily? | 0.608 |

| How often do you consume food rich in dietary fiber? | 0.713 |

| To what extent do you agree with the following statement: “I watch what I eat to maintain my health”? | 0.765 |

| How much do you agree with the following statement: “I watch what I eat to maintain a good appearance and prevent weight gain”? | 0.644 |

| Are you reading food labels; particularly nutritional values and ingredient list on food products? | 0.615 |

| Explanation of variance | 45% |

| Eigenvalue | 2.257 |

| Sustainability knowledge score | |

| Are you familiar with the term Sustainable Development? | 0.533 |

| How much do you agree with the following statement: “Edible films are active packaging systems that extend product shelf life, improve product quality, and contribute to the nutritional quality of the final product”? | −0.798 |

| To what extent do you agree with the following statement: “Grape and/or aronia pomace is a byproduct of the food industry rich in dietary fiber and polyphenols”? | −0.806 |

| Explanation of variance | 52% |

| Eigenvalue | 1.57 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Molnar, D.; Velickova, E.; Prost, C.; Temkov, M.; Ščetar, M.; Novotni, D. Consumer Nutritional Awareness, Sustainability Knowledge, and Purchase Intention of Environmentally Friendly Cookies in Croatia, France, and North Macedonia. Foods 2023, 12, 3932. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12213932

Molnar D, Velickova E, Prost C, Temkov M, Ščetar M, Novotni D. Consumer Nutritional Awareness, Sustainability Knowledge, and Purchase Intention of Environmentally Friendly Cookies in Croatia, France, and North Macedonia. Foods. 2023; 12(21):3932. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12213932

Chicago/Turabian StyleMolnar, Dunja, Elena Velickova, Carole Prost, Mishela Temkov, Mario Ščetar, and Dubravka Novotni. 2023. "Consumer Nutritional Awareness, Sustainability Knowledge, and Purchase Intention of Environmentally Friendly Cookies in Croatia, France, and North Macedonia" Foods 12, no. 21: 3932. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12213932

APA StyleMolnar, D., Velickova, E., Prost, C., Temkov, M., Ščetar, M., & Novotni, D. (2023). Consumer Nutritional Awareness, Sustainability Knowledge, and Purchase Intention of Environmentally Friendly Cookies in Croatia, France, and North Macedonia. Foods, 12(21), 3932. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12213932