Applicable Strains, Processing Techniques and Health Benefits of Fermented Oat Beverages: A Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Strains

2.1. Lactic Acid Bacteria

2.2. Yeasts

2.3. Mixed Strains

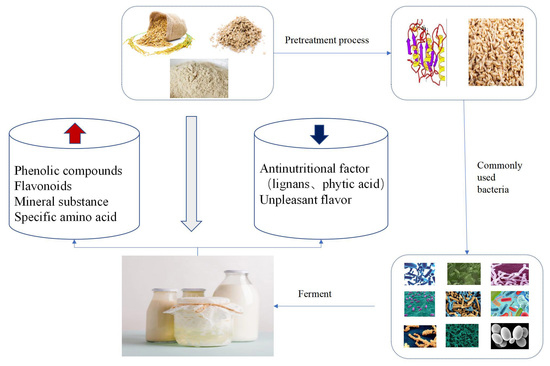

3. Processing Techniques

3.1. Pre-Treatments

| Pre-Treatments | Changes in the Bioactive Components in Oat | References |

|---|---|---|

| Enzymatic hydrolysis | Increase soluble and insoluble phenolics. Fermentation following enzymatic hydrolysis upgraded the antioxidant activity and α-glucosidase, α-amylase inhibition activities of oat. | [63] |

| Sprouting | Obtain a novel gluten-free and healthy ingredient, excellent levels of protein, micronutrients and β-glucan. Present balanced amino acid and fatty acid compositions. Increased free phenolics, GABA and antioxidant activity in oat powder. Present high protease/α-amylase and low lipase activities. | [64] |

| Malting | Increase the concentration in phenolic compounds. Increase number of compounds present in the malt. Increase the antioxidative potential of grains. | [62] |

| De-branning | Increase the digestibility rates and decrease phytic acid content significantly. The mineral digestibility raised for all grain samples. Lead to an increase in the protein content of oat flour after separated the bran. | [65] |

| Drying | Induce starch gelatinization, protein modification. Increase nutrient availability and provide inactivation of heat-labile toxic compounds and other enzyme inhibitors. Lead to a unique sensory and nutritional profile to the oat. | [66] |

| Milling | Decrease the level of phytic acid. | [67] |

| Increase protein digestibility in all flour samples. | [68] | |

| The oat-milling process is different compared to the milling of other cereal grains as it includes a heat treatment step, namely kilning, which is performed to inactivate the endogenous lipid-degrading enzymes. | [69] | |

| Grinding | Improve the dispersibility, solubility, water retention, antioxidant property, and other important physical and chemical properties | [70] |

3.2. Fermentation Conditions

4. Health Benefits

4.1. Bioactive Compounds

4.2. Functionality

5. Conclusions and Prospects

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Montemurro, M.; Pontonio, E.; Coda, R.; Rizzello, C.G. Plant-Based Alternatives to Yogurt: State-of-the-Art and Perspectives of New Biotechnological Challenges. Foods 2021, 10, 316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelov, A.; Yaneva-Marinova, T.; Gotcheva, V. Oats as a matrix of choice for developing fermented functional beverages. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2018, 55, 2351–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristek, A.; Wiese, M.; Heuer, P.; Kosik, O.; Schär, M.Y.; Soycan, G.; Alsharif, S.; Kuhnle, G.G.; Walton, G.; Spencer, J.P. Oat bran, but not its isolated bioactive β-glucans or polyphenols, have a bifidogenic effect in an in vitro fermentation model of the gut microbiota. Br. J. Nutr. 2019, 121, 549–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babolanimogadam, N.; Gandomi, H.; Basti, A.A.; Taherzadeh, M.J. Nutritional, functional, and sensorial properties of oat milk produced by single and combined acid, alkaline, α-amylase, and sprouting treatments. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 11, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayachandran, M.; Chen, J.; Chung, S.S.M.; Xu, B. A critical review on the impacts of β-glucans on gut microbiota and human health. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2018, 61, 101–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, E.J.; Rezoagli, E.; Major, I.; Rowan, N.J.; Laffey, J.G. β-Glucan Metabolic and Immunomodulatory Properties and Potential for Clinical Application. J. Fungi 2020, 6, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maheshwari, G.; Sowrirajan, S.; Joseph, B. β-Glucan, a dietary fiber in effective prevention of lifestyle diseases—An insight. Bioact. Carbohydr. Diet. Fibre 2019, 19, 100187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majtan, J.; Jesenak, M. β-Glucans: Multi-Functional Modulator of Wound Healing. Molecules 2018, 23, 806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, M. Cereal beta-glucans: An underutilized health endorsing food ingredient. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 62, 3281–3300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Zhu, Y.; Li, Y.; Qi, X.; Yang, J.; Qi, H.; Li, Q.; Ma, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, X.; et al. A Bifunctional Zwitterion-Modified Porphyrin for Photodynamic Nondestructive Tooth Whitening and Biofilm Eradication. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31, 2104799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wronkowska, M.; Rostek, D.; Lenkiewicz, M.; Kurantowicz, E.; Yaneva, T.G.; Starowicz, M. Oat flour fermented by Lactobacillus strains—Kinetics of volatile compound formation and antioxidant capacity. J. Cereal Sci. 2021, 103, 103392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marco, M.L.; Heeney, D.; Binda, S.; Cifelli, C.J.; Cotter, P.D.; Foligné, B.; Gänzle, M.; Kort, R.; Pasin, G.; Pihlanto, A.; et al. Health benefits of fermented foods: Microbiota and beyond. Curr. Opin. Biotechnol. 2017, 44, 94–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menezes, A.G.T.; Ramos, C.L.; Dias, D.R.; Schwan, R.F. Combination of probiotic yeast and lactic acid bacteria as starter culture to produce maize-based beverages. Food Res. Int. 2018, 111, 187–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mituniewicz–Małek, A.; Zielińska, D.; Ziarno, M. Probiotic monocultures in fermented goat milk beverages—Sensory quality of final product. Int. J. Dairy Technol. 2019, 72, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Liu, W.; Wei, Z.; Yin, B.; Man, C.; Jiang, Y. Enhancement of functional characteristics of blueberry juice fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum. LWT 2021, 139, 110590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, M.; Bajaj, B.K. Development of fermented oat flour beverage as a potential probiotic vehicle. Food Biosci. 2017, 20, 104–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, M.; Kokkiligadda, A.; Dasriya, V.; Naithani, H. Functional relevance and health benefits of soymilk fermented by lactic acid bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2022, 133, 104–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Achi, O.K.; Asamudo, N.U. Cereal-Based Fermented Foods of Africa as Functional Foods. In Bioactive Molecules in Food; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2019; pp. 1527–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şanlıbaba, P. Fermented nondairy functional foods based on probiotics. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2023, 35, 91–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klajn, V.M.; Ames, C.W.; da Cunha, K.F.; Lorini, A.; Hackbart, H.C.d.S.; Cruxen, C.E.d.S.; Fiorentini, Â.M. Technology. Probiotic fermented oat dairy beverage: Viability of Lactobacillus casei, fatty acid profile, phenolic compound content and acceptability. J. Food Sci. Fiorentini Technol. 2021, 58, 3444–3452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herrera-Ponce, A.; Nevárez-Morillón, G.; Ortega-Rívas, E.; Pérez-Vega, S.; Salmerón, I. Fermentation adaptability of three probiotic L actobacillus strains to oat, germinated oat and malted oat substrates. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 59, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Rui, X.; Li, W.; Xiao, Y.; Zhou, J.; Dong, M. Whole-grain oats (Avena sativa L.) as a carrier of lactic acid bacteria and a supplement rich in angiotensin I-converting enzyme inhibitory peptides through solid-state fermentation. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 2270–2281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bai, J.; Li, Y.; Zhang, W.; Fan, M.; Qian, H.; Zhang, H.; Qi, X.; Wang, L. Source of gut microbiota determines oat β-glucan degradation and short chain fatty acid-producing pathway. Food Biosci. 2021, 41, 101010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goncerzewicz, A.; Misiewicz, A.; Owczarek, L.; Jasińska, U.; Skąpska, S. The Effect of a Newly Developed Oat-Banana Fermented Beverage with a Beta-glucan Additive on ldhL Gene Expression in Streptococcus thermophilus TKM3 KKP 2030p. Curr. Microbiol. 2016, 73, 773–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kocková, M.; Valík, Ľ. Development of new cereal-, pseudocereal-, and cereal-leguminous-based probiotic foods. Czech J. Food Sci. 2014, 32, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Masiá, C.; Geppel, A.; Jensen, P.E.; Buldo, P. Effect of Lactobacillus rhamnosus on Physicochemical Properties of Fermented Plant-Based Raw Materials. Foods 2021, 10, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Angelov, A.; Gotcheva, V.; Hristozova, T.; Gargova, S. Application of pure and mixed probiotic lactic acid bacteria and yeast cultures for oat fermentation. J. Sci. Food Agric. 2005, 85, 2134–2141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gokavi, S.; Zhang, L.; Huang, M.K.; Zhao, X.; Guo, M. Oat-based Symbiotic Beverage Fermented by Lactobacillus plantarum, Lactobacillus paracasei ssp. casei, and Lactobacillus acidophilus. J. Food Sci. 2005, 70, M216–M223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kedia, G.; Vázquez, J.A.; Pandiella, S.S. Enzymatic digestion and in vitro fermentation of oat fractions by human lactobacillus strains. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2008, 43, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczepaniak, G.; Wojtatowicz, M. Dobór szczepów Yarrowia lipolytica i Debaryomyces hansenii do szczepionki wspomagającej proces dojrzewania sera. Żywność Nauka Technol. Jakość 2011, 18, 192–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Călinoiu, L.F.; Cătoi, A.-F.; Vodnar, D.C. Solid-State Yeast Fermented Wheat and Oat Bran as A Route for Delivery of Antioxidants. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyer, L.C.; Zannini, E.; Jacob, F.; Arendt, E.K. Growth Study, Metabolite Development, and Organoleptic Profile of a Malt-Based Substrate Fermented by Lactic Acid Bacteria. J. Am. Soc. Brew. Chem. 2015, 73, 303–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asadzadeh, A.; Jalali, H.; Azizi, M.H.; Nafchi, A.M. Production of oat bran functional probiotic beverage using Bifidobacterium lactis. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2020, 15, 1301–1309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, P.; Enespa; Singh, R.; Arora, P.K. Microbial lipases and their industrial applications: A comprehensive review. Microb. Cell Fact. 2020, 19, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.; Wu, D.; Schlundt, J.; Conway, P.L. Development of a Dairy-Free Fermented Oat-Based Beverage with Enhanced Probiotic and Bioactive Properties. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 609734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Zhang, H.; Wang, T.; Wang, R.; Luo, X. Effects of Five Different Lactic Acid Bacteria on Bioactive Components and Volatile Compounds of Oat. Foods 2022, 11, 3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-Y.; Jo, Y.-J.; Choi, M.-J.; Lee, B.-Y.; Han, J.-K.; Lim, J.K.; Oh, J.-W. Effect of Coating Method on the Survival Rate of L. plantarum for Chicken Feed. Korean J. Food Sci. Anim. Resour. 2014, 34, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Capurso, L. Thirty years of Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG: A review. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2019, 53, S1–S41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coman, M.M.; Verdenelli, M.C.; Cecchini, C.; Silvi, S.; Vasile, A.; Bahrim, G.E.; Orpianesi, C.; Cresci, A. Effect of buckwheat flour and oat bran on growth and cell viability of the probiotic strains Lactobacillus rhamnosus IMC 501®, Lactobacillus paracasei IMC 502® and their combination SYNBIO®, in synbiotic fermented milk. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2013, 167, 261–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luana, N.; Rossana, C.; Curiel, J.A.; Kaisa, P.; Marco, G.; Rizzello, C.G. Manufacture and characterization of a yogurt-like beverage made with oat flakes fermented by selected lactic acid bacteria. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2014, 185, 17–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aparicio-García, N.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Frias, J.; Peñas, E. Production and Characterization of a Novel Gluten-Free Fermented Beverage Based on Sprouted Oat Flour. Foods 2021, 10, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Chan, S.H.J.; Chen, J.; Solem, C.; Jensen, P.R. Systems Biology—A Guide for Understanding and Developing Improved Strains of Lactic Acid Bacteria. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petrova, P.; Petrov, K. Lactic Acid Fermentation of Cereals and Pseudocereals: Ancient Nutritional Biotechnologies with Modern Applications. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, A.O.; Goldman, E.A.; Brooks, J.T.; Golomb, B.L.; Yim, I.S.; Gotcheva, V.; Angelov, A.; Kim, E.B.; Marco, M.L. Strain diversity of plant-associated Lactiplantibacillus plantarum. Microb. Biotechnol. 2021, 14, 1990–2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aparicio-García, N.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Frias, J.; Peñas, E. Sprouted oat as a potential gluten-free ingredient with enhanced nutritional and bioactive properties. Food Chem. 2020, 338, 127972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunderam, V.; Mohammed, S.S.S.; Madhavan, Y.; Dhinakaran, M.; Sampath, S.; Patteswaran, N.; Thangavelu, L.; Lawrence, A.V. Free radical scavenging activity and cytotoxicity study of fermented oats (Avena sativa). Int. J. Res. Pharm. Sci. 2020, 11, 1259–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajam, R.; Karthik, P.; Parthasarathi, S.; Joseph, G.; Anandharamakrishnan, C. Effect of whey protein—Alginate wall systems on survival of microencapsulated Lactobacillus plantarum in simulated gastrointestinal conditions. J. Funct. Foods 2012, 4, 891–898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roux, E.; Nicolas, A.; Valence, F.; Siekaniec, G.; Chuat, V.; Nicolas, J.; Le Loir, Y.; Guédon, E. The genomic basis of the Streptococcus thermophilus health-promoting properties. BMC Genom. 2022, 23, 210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, M.R.; Azizi, N.F.; Yeap, S.K.; Abdullah, J.O.; Khalid, M.; Omar, A.R.; Osman, M.A.; Leow, A.T.C.; Mortadza, S.A.S.; Alitheen, N.B. Clinical and Preclinical Studies of Fermented Foods and Their Effects on Alzheimer’s Disease. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dąbrowski, G.; Paulauskienė, A.; Baltušnikienė, A.; Kłębukowska, L.; Czaplicki, S.; Konopka, I. Changes in Selected Quality Indices in Microbially Fermented Commercial Almond and Oat Drinks. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 9983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyanzi, R.; Jooste, P. Cereal-Based Functional Foods. Probiotics 2012, 8, 161–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barajas-Álvarez, P.; González-Ávila, M.; Espinosa-Andrews, H. Microencapsulation of Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 by spray drying and its evaluation under gastrointestinal and storage conditions. LWT 2022, 153, 112485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermudez-Brito, M.; Borghuis, T.; Daniel, C.; Pot, B.; de Haan, B.J.; Faas, M.M.; de Vos, P. L. plantarum WCFS1 enhances Treg frequencies by activating DCs even in absence of sampling of bacteria in the Peyer Patches. Sci. Rep. 2018, 8, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schär, M.Y.; Corona, G.; Soycan, G.; Dine, C.; Kristek, A.; Alsharif, S.N.S.; Behrends, V.; Lovegrove, A.; Shewry, P.R.; Spencer, J.P.E. Excretion of Avenanthramides, Phenolic Acids and their Major Metabolites Following Intake of Oat Bran. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2017, 62, 1700499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bei, Q.; Chen, G.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, Z. Improving phenolic compositions and bioactivity of oats by enzymatic hydrolysis and microbial fermentation. J. Funct. Foods 2018, 47, 512–520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hefni, M.E.; Amann, L.S.; Witthöft, C.M. A HPLC-UV Method for the Quantification of Phenolic Acids in Cereals. Food Anal. Methods 2019, 12, 2802–2812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valero-Cases, E.; Cerdá-Bernad, D.; Pastor, J.-J.; Frutos, M.-J. Non-Dairy Fermented Beverages as Potential Carriers to Ensure Probiotics, Prebiotics, and Bioactive Compounds Arrival to the Gut and Their Health Benefits. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rico, D.; Peñas, E.; García, M.d.C.; Martínez-Villaluenga, C.; Rai, D.K.; Birsan, R.I.; Frias, J.; Martín-Diana, A.B. Sprouted Barley Flour as a Nutritious and Functional Ingredient. Foods 2020, 9, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomé-Sánchez, I.; Martín-Diana, A.B.; Peñas, E.; Bautista-Expósito, S.; Frias, J.; Rico, D.; González-Maillo, L.; Martinez-Villaluenga, C. Soluble Phenolic Composition Tailored by Germination Conditions Accompany Antioxidant and Anti-Inflammatory Properties of Wheat. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboulfazli, F.; Shori, A.B.; Baba, A.S. Effects of the replacement of cow milk with vegetable milk on probiotics and nutritional profile of fermented ice cream. LWT 2016, 70, 261–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Angelov, A.; Gotcheva, V.; Kuncheva, R.; Hristozova, T. Development of a new oat-based probiotic drink. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 112, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasiński, A.; Kawa-Rygielska, J.; Błażewicz, J.; Leszczyńska, D. Malting procedure and its impact on the composition of volatiles and antioxidative potential of naked and covered oat varieties. J. Cereal Sci. 2022, 107, 103537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haard, N.; Odunfa, S.; Lee, C.; Quintero-Ramírez, R.; Lorence-Quinones, A.; Wacher-Rodarte, C. Cereals: Rationale for fermentation. J. Fermented Cereals Glob. Perspect. 1999, 1, 1–27. [Google Scholar]

- Sangwan, S.; Singh, R.; Tomar, S.K. Nutritional and functional properties of oats: An update. J. Innov. Biol. 2014, 1, 3–14. [Google Scholar]

- Kedia, G.; Vázquez, J.A.; Pandiella, S.S. Evaluation of the fermentability of oat fractions obtained by debranning using lactic acid bacteria. J Appl Microbiol. 2008, 105, 1227–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Şanlier, N.; Gökcen, B.B.; Sezgin, A.C. Health benefits of fermented foods. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 59, 506–527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Xiao, X.; Dong, Y.; Shi, L.; Xu, T.; Wu, F. The anti-obesity effect of fermented barley extracts with Lactobacillus plantarum dy-1 and Saccharomyces cerevisiae in diet-induced obese rats. Food Funct. 2017, 8, 1132–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeghate, E.; Ponery, A. GABA in the endocrine pancreas: Cellular localization and function in normal and diabetic rats. Tissue Cell 2002, 34, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jokinen, I.; Silventoinen-Veijalainen, P.; Lille, M.; Nordlund, E.; Holopainen-Mantila, U. Variability of carbohydrate composition and pasting properties of oat flakes and oat flours produced by industrial oat milling process—Comparison to non-heat-treated oat flours. Food Chem. 2023, 405, 134902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Cox, S.; Abu-Ghannam, N. Process optimization for the development of a functional beverage based on lactic acid fermentation of oats. Biochem. Eng. J. 2010, 52, 199–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmed, A.; Batool, K.; Bibi, A.J.J.o.A.; Microbiology, E. Microbial β-glucosidase: Sources, production and applications. J. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 5, 31–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soycan, G.; Schär, M.Y.; Kristek, A.; Boberska, J.; Alsharif, S.N.; Corona, G.; Shewry, P.R.; Spencer, J.P. Composition and content of phenolic acids and avenanthramides in commercial oat products: Are oats an important polyphenol source for consumers? Food Chem. X 2019, 3, 100047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tang, Y.; Li, S.; Yan, J.; Peng, Y.; Weng, W.; Yao, X.; Gao, A.; Cheng, J.; Ruan, J.; Xu, B. Bioactive Components and Health Functions of Oat. Food Rev. Int. 2022, 133, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mäkinen, O.E.; Wanhalinna, V.; Zannini, E.; Arendt, E.K. Foods for Special Dietary Needs: Non-dairy Plant-based Milk Substitutes and Fermented Dairy-type Products. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2016, 56, 339–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, E.Q.; Chacko, S.A.; Chou, E.L.; Kugizaki, M.; Liu, S. Greater Whole-Grain Intake Is Associated with Lower Risk of Type 2 Diabetes, Cardiovascular Disease, and Weight Gain. J. Nutr. 2012, 142, 1304–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adebo, O.A.; Gabriela Medina-Meza, I.J.M. Impact of fermentation on the phenolic compounds and antioxidant activity of whole cereal grains: A mini review. Molecules 2020, 25, 927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.; Koecher, K.; Hansen, L.; Ferruzzi, M.G. Phenolics from Whole Grain Oat Products as Modifiers of Starch Digestion and Intestinal Glucose Transport. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2017, 65, 6831–6839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verni, M.; Verardo, V.; Rizzello, C. How Fermentation Affects the Antioxidant Properties of Cereals and Legumes. Foods 2019, 8, 362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhen, Y.; Chong, X.; Yulong, B.; Fengyuan, L.; Haiyan, W.; Yaqin, W. Oat: Current state and challenges in plant-based food applications. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2023, 134, 56–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coda, R.; Rizzello, C.G.; Trani, A.; Gobbetti, M. Manufacture and characterization of functional emmer beverages fermented by selected lactic acid bacteria. Food Microbiol. 2011, 28, 526–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Liu, P.; Qin, J.; Song, L.; Yang, W.; Feng, M.; Zhang, M.; Wang, C.; Song, X. Effects of Applying Different Doses of Selenite to Soil and Foliar at Different Growth Stage on Selenium Content and Yield of Different Oat Varieties. Plants 2022, 11, 1810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grundy, M.M.L.; Fardet, A.; Tosh, S.M.; Rich, G.T.; Wilde, P.J. Processing of oat: The impact on oat’s cholesterol lowering effect. Food Funct. 2018, 9, 1328–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Algonaiman, R.; Alharbi, H.F.; Barakat, H. Antidiabetic and Hypolipidemic Efficiency of Lactobacillus plantarum Fermented Oat (Avena sativa) Extract in Streptozotocin-Induced Diabetes in Rats. Fermentation 2022, 8, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, M.; Guo, X.; Bai, X.; Zhang, J.; Huo, R.; Zhang, Y. Improving the adsorption characteristics and antioxidant activity of oat bran by superfine grinding. Food Sci. Nutr. 2022, 11, 216–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whitehead, A.; Beck, E.J.; Tosh, S.; Wolever, T.M. Cholesterol-lowering effects of oat β-glucan: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2014, 100, 1413–1421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mårtensson, O.; Biörklund, M.; Lambo, A.M.; Dueñas-Chasco, M.; Irastorza, A.; Holst, O.; Norin, E.; Welling, G.; Öste, R.; Önning, G. Fermented, ropy, oat-based products reduce cholesterol levels and stimulate the bifidobacteria flora in humans. Nutr. Res. 2005, 25, 429–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jadhav, K.B.; Gupta, N. Clinicopathological prognostic implicators of oral squamous cell carcinoma: Need to understand and revise. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 5, 671–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eghbali, S.; Askari, S.F.; Avan, R.; Sahebkar, A. Therapeutic Effects of Punica granatum (Pomegranate): An Updated Review of Clinical Trials. J. Nutr. Metab. 2021, 2021, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Strains | Fermentation Substrates | Descriptions | Functions | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG | Boil oats mixed with water | Highest growth rate in the oat product. It is able to survive in fermented products during storage at refrigerating temperature, with its metabolic activity continuing. | Anti-inflammatory | [25,26] |

| Streptococcus thermophilus TKM3 KKP 2030p | An oat–banana matrix with Prom Oat additive | Acceptable sensory characteristics and large amounts of lactic acid bacteria were obtained during 4 weeks of cold storage. | Accelerated substrate fermentation | [24] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum B28 | Oat mash | Most intensive acid formation was registered for strain Lactobacillus plantarum B28, with the pH of the oat medium reaching values below 4.5 after 6 h. | Cholesterol lowering | [27,28] |

| L. casei spp. paracasei B29 | A good balance between acid formation and cell counts was observed for strains L. plantarum B28 and L. casei spp paracasei B29. | Cholesterol lowering | ||

| Candida rugosa Y28 | At the end of the fermentation, the highest cell counts were obtained for strains L. plantarum B28 and C. rugosa Y28 as 2.81 and 2.71 log orders, respectively. | —— | [27] | |

| C. lambica Y30 | Strain Y30 completed fermentation for 10 h. | —— | ||

| Lactobacillus reuteri (NCIMB 11951) | Oat bran and whole flour | Grow well in the 1–3% pearling fraction, whole flour and bran. | Immunomodulation | [29,30] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum (NCIMB 8826) | Immunomodulation Anti-inflammatory | [29,31,32] | ||

| Lactobacillus acidophilus (NCIMB 8821) | The growth limitations of this strain in cereal media. | —— | [29] | |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus LGG | Oat concentrate | Acetoin levels increased and acetaldehyde content decreased. No significant effect on rheological behavior was observed when L. rhamnosus was present in fermented samples. L. rhamnosus significantly enhanced fermented flavor notes, such as sourness, lemon, and fruity taste. Reduce fermentation time. | Improved texture and flavor | [26] |

| Bifidobacterium lactis | Oat bran extract | The viability of probiotic was 109 CFU/mL at pH = 4.2, while by decreasing the pH to 4.0, the viability decreased to 107 CFU/mL. | Anti-diabetes | [33,34] |

| Lactobacillus fermentum PC1 | Oats with added honey | Good survival. An increase of more than 50% of gallic acid, catechin, vanillic acid, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, and ferulic acid was observed in the methanol extracts. No significant decrease in the β-glucan content was noted during fermentation and storage. | Anti-inflammatory | [35,36] |

| Lactobacillus casei (431) | Germinated and malted oat substrates | In the germinated oat media, Lactobacillus casei presented the highest maximal growth in this medium. Lactobacillus casei showed high adaptability during fermentation. Lactobacillus casei 431 can produce more typical flavor compounds, such as 2-butanedione, 2-heptanone, acetylurea and 2-nonone. | Improved texture and flavor | [21,37] |

| Lactobacillus acidophilus (LA-5) | The oat substrates can support the growth of Lact. acidophilus, Lact. casei and Lact. rhamnosus at probiotic levels comparable to the conventional dairy-based substrates. | —— | [21] | |

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus HN001 | Regulation of intestinal flora | [21,38] | ||

| Lactobacillus rhamnosus IMC 501® | Oat bran | Our study has demonstrated the prebiotic potential of oat bran for lactobacillus. | Accelerated substrate fermentation | [39] |

| Lactobacillus paracasei IMC 502® | ||||

| Lactobacillus plantarum LP09 | Oat flakes | The beverage started with L. plantarum LP09; it had optimal values for all sensory attributes and the most balanced profile. | Improved texture and flavor | [40] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum M-13 | Oat flour | It showed excellent survival rate under simulated gastrointestinal tract (GIT) conditions and had a variety of desirable functional properties, such as adhesion, auto aggregation and coaggregation potential, extracellular enzyme production, antibacterial activity and antibiotic sensitivity. | Antibacterial activity and antibiotic sensitivity | [16] |

| Lactobacillus plantarum WCFS1 | Sprouted oat flour | The results showed that sprouted oat flour is a suitable substrate that supports the fast growth and high viability of L. plantarum WCFS1 strain. | Anti-inflammatory | [35,41] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yu, Q.; Qian, J.; Guo, Y.; Qian, H.; Yao, W.; Cheng, Y. Applicable Strains, Processing Techniques and Health Benefits of Fermented Oat Beverages: A Review. Foods 2023, 12, 1708. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12081708

Yu Q, Qian J, Guo Y, Qian H, Yao W, Cheng Y. Applicable Strains, Processing Techniques and Health Benefits of Fermented Oat Beverages: A Review. Foods. 2023; 12(8):1708. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12081708

Chicago/Turabian StyleYu, Qian, Jiaqin Qian, Yahui Guo, He Qian, Weirong Yao, and Yuliang Cheng. 2023. "Applicable Strains, Processing Techniques and Health Benefits of Fermented Oat Beverages: A Review" Foods 12, no. 8: 1708. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12081708

APA StyleYu, Q., Qian, J., Guo, Y., Qian, H., Yao, W., & Cheng, Y. (2023). Applicable Strains, Processing Techniques and Health Benefits of Fermented Oat Beverages: A Review. Foods, 12(8), 1708. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods12081708