High-Performance Detection of Mycobacterium bovis in Milk Using Recombinase-Aided Amplification–Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat–Cas13a–Lateral Flow Detection

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Bacteria Culture and DNA Extraction

2.2. Recombinase-Aided Amplification (RPA) Primer Sequences and crisprRNA (crRNA) Preparation

2.3. Preparation of Recombinant pUC57-MPB70 Plasmid

2.4. RPA Reactions

2.5. RPA–CRISPR–Cas13a–LFD

2.6. RPA–CRISPR–Cas13a–Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qPCR)

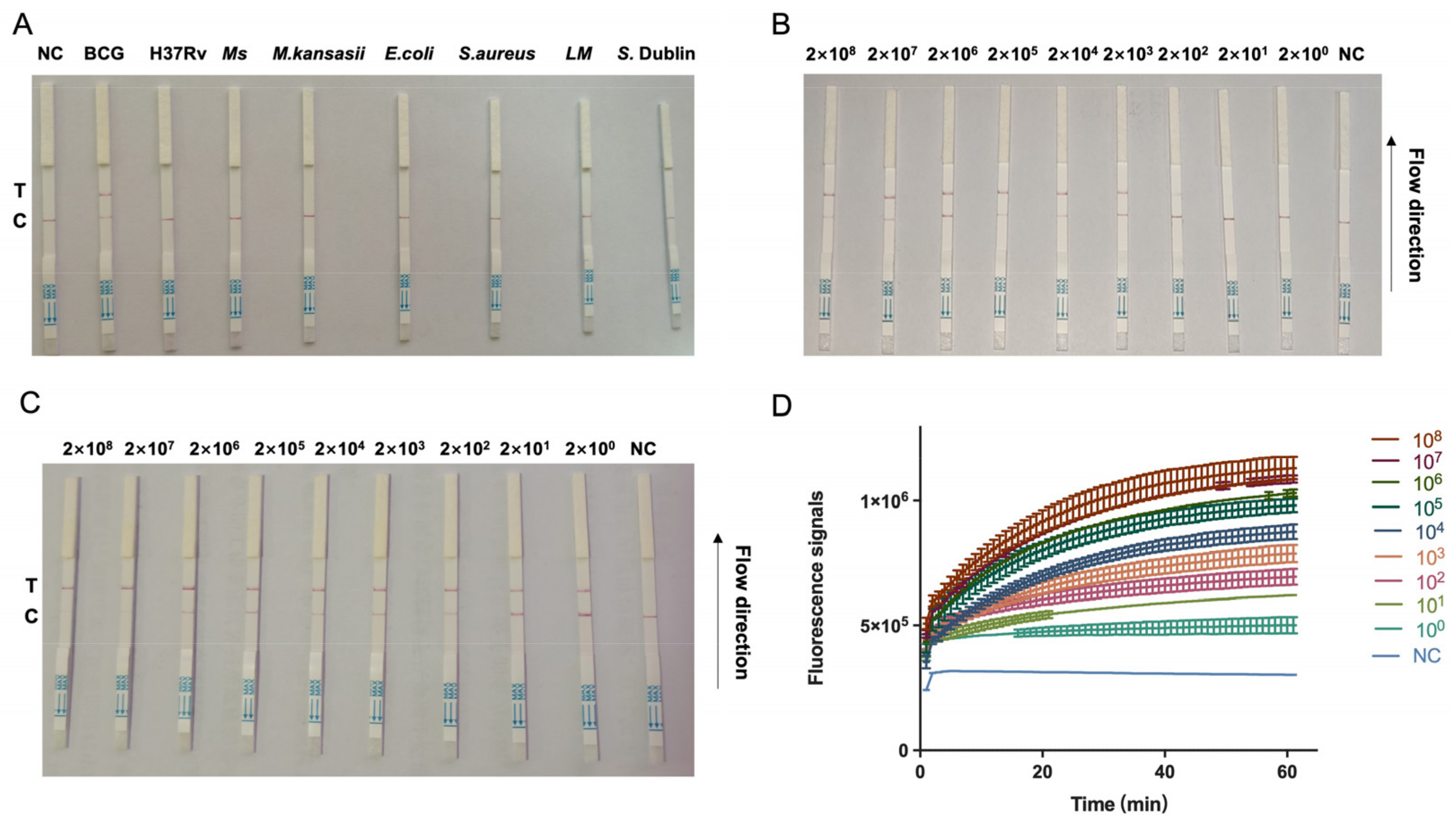

2.7. Analytical Sensitivity and Specificity of RPA–CRISPR–Cas13a–LFD

2.8. Preparation of Milk Samples and DNA Extraction

2.9. Milk ELISA

2.10. Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Optimizing the Primers for CRISPR–Cas13a-Based bTB Detection Platform

3.2. Identification of High-Activity crRNAs for bTB Detection

3.3. Establishment of CRISPR–Cas13a Combined with RPA Amplification for Detection of bTB

3.4. Detection of bTB in Clinical Milk Samples by RPA–CRISPR–Cas13a–LFD

4. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roug, A.; Perez, A.; Mazet, J.A.; Clifford, D.L.; VanWormer, E.; Paul, G.; Kazwala, R.R.; Smith, W.A. Comparison of intervention methods for reducing human exposure to Mycobacterium bovis through milk in pastoralist households of Tanzania. Prev. Vet. Med. 2014, 115, 157–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ereqat, S.; Nasereddin, A.; Levine, H.; Azmi, K.; Al-Jawabreh, A.; Greenblatt, C.L.; Abdeen, Z.; Bar-Gal, G.K. First-time detection of Mycobacterium bovis in livestock tissues and milk in the West Bank, Palestinian Territories. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2013, 7, e2417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolanos, C.A.D.; Paula, C.L.; Guerra, S.T.; Franco, M.M.J.; Ribeiro, M.G. Diagnosis of mycobacteria in bovine milk: An overview. Rev. Inst. Med. Trop. Sao Paulo 2017, 59, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgrave, R.; Donaghy, J.A.; Fisher, A.; Rowe, M.T. Optimization of modified Middlebrook 7H11 agar for isolation of Mycobacterium bovis from raw milk cheese. Lett. Appl. Microbiol. 2014, 59, 384–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cadmus, S.I.; Yakubu, M.K.; Magaji, A.A.; Jenkins, A.O.; van Soolingen, D. Mycobacterium bovis, but also M. africanum present in raw milk of pastoral cattle in north-central Nigeria. Trop. Anim. Health Prod. 2010, 42, 1047–1048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarden, C.F.; Marassi, C.D.; Figueiredo, E.E.; Lilenbaum, W. Mycobacterium bovis detection from milk of negative skin test cows. Vet. Rec. 2013, 172, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rennie, B.; Filion, L.G.; Smart, N. Antibody response to a sterile filtered PPD tuberculin in M. bovis infected and M. bovis sensitized cattle. BMC Vet. Res. 2010, 6, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsohaby, I.; Mahmmod, Y.S.; Mweu, M.M.; Ahmed, H.A.; El-Diasty, M.M.; Elgedawy, A.A.; Mahrous, E.; El Hofy, F.I. Accuracy of PCR, mycobacterial culture and interferon-gamma assays for detection of Mycobacterium bovis in blood and milk samples from Egyptian dairy cows using Bayesian modelling. Prev. Vet. Med. 2020, 181, 105054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquetoux, N.; Vignes, M.; Burroughs, A.; Sumner, E.; Sawford, K.; Jones, G. Evaluation of the accuracy of the IDvet serological test for Mycoplasma bovis infection in cattle using latent class analysis of paired serum ELISA and quantitative real-time PCR on tonsillar swabs sampled at slaughter. PLoS ONE 2023, 18, e0285598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Yan, L.; Li, J.; Chen, Y.; Hu, C.; Robertson, I.D.; Guo, A.; Aleri, J. Evaluation of an ELISA for the diagnosis of bovine tuberculosis using milk samples from dairy cows in China. Prev. Vet. Med. 2022, 208, 105752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.Y.; Zhu, X.; Kim, S.M.; Lim, J.A.; Woo, M.A.; Lim, M.C.; Luo, K. A review of nucleic acid-based detection methods for foodborne viruses: Sample pretreatment and detection techniques. Food Res. Int. 2023, 174, 113502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mascarenhas, D.R.; Schwarz, D.G.G.; Fonseca Junior, A.A.; Oliveira, T.F.P.; Moreira, M.A.S. Validation of real-time PCR technique for detection of Mycobacterium bovis and Brucella abortus in bovine raw milk. Braz. J. Microbiol. 2020, 51, 2095–2100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Qiu, M.; Li, X.; Yang, J.; Li, J. CRISPR-Cas13a system: A novel tool for molecular diagnostics. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 1060947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gootenberg, J.S.; Abudayyeh, O.O.; Lee, J.W.; Essletzbichler, P.; Dy, A.J.; Joung, J.; Verdine, V.; Donghia, N.; Daringer, N.M.; Freije, C.A.; et al. Nucleic acid detection with CRISPR-Cas13a/C2c2. Science 2017, 356, 438–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Man, S.; Ye, S.; Liu, G.; Ma, L. CRISPR-Cas based virus detection: Recent advances and perspectives. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 193, 113541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fozouni, P.; Son, S.; Diaz de Leon Derby, M.; Knott, G.J.; Gray, C.N.; D’Ambrosio, M.V.; Zhao, C.; Switz, N.A.; Kumar, G.R.; Stephens, S.I.; et al. Amplification-free detection of SARS-CoV-2 with CRISPR-Cas13a and mobile phone microscopy. Cell 2021, 184, 323–333.e329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yin, L.; Dong, Y.; Peng, L.; Liu, G.; Man, S.; Ma, L. CRISPR-Cas13a based bacterial detection platform: Sensing pathogen Staphylococcus aureus in food samples. Anal. Chim. Acta 2020, 1127, 225–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, T.; Zhou, W.; Lin, X.; Khan, M.R.; Deng, S.; Zhou, M.; He, G.; Wu, C.; Deng, R.; He, Q. Light-up RNA aptamer signaling-CRISPR-Cas13a-based mix-and-read assays for profiling viable pathogenic bacteria. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2021, 176, 112906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Tian, Y.; Xu, L.; Fan, Z.; Cao, Y.; Ma, Y.; Li, H.; Ren, F. CRISPR/Cas13-assisted hepatitis B virus covalently closed circular DNA detection. Hepatol. Int. 2022, 16, 306–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, L.; Wang, Z.; Wang, Y.; Luan, J.; Morrissey, J.J.; Naik, R.R.; Singamaneni, S. Plasmonically Enhanced CRISPR/Cas13a-Based Bioassay for Amplification-Free Detection of Cancer-Associated RNA. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2021, 10, e2100956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhu, X.; Yin, D.; Cai, C.; Liu, H.; Yang, Y.; Guo, Z.; Yin, L.; Shen, X.; Dai, Y.; et al. Rapid and Easy-Read Porcine Circovirus Type 4 Detection with CRISPR-Cas13a-Based Lateral Flow Strip. Microorganisms 2023, 11, 354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, Q.; Wang, R.; Wang, L.; Wang, X.; Luo, J.; Xing, G.; Zheng, G.; Wan, B.; Guo, J.; et al. Differentiation of Classical Swine Fever Virus Virulent and Vaccine Strains by CRISPR/Cas13a. Microbiol. Spectr. 2022, 10, e0089122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ren, W.; Zhou, Y.; Li, H.; Shang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Yuan, J.; Li, S.; Li, C.; Pang, Y. Development and clinical evaluation of a CRISPR/Cas13a-based diagnostic test to detect Mycobacterium tuberculosis in clinical specimens. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1117085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, G.; Peng, Y.; Liu, G.Q.; Jiang, H.; Feng, Y.; Zhu, L.Q.; Ding, J.B. Use of multiplex PCR assay for the identification of Mycobacterium avium sub-species. Chin. J. Vet. Drug 2017, 51, 11–17. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Watson, P.F.; Petrie, A. Method agreement analysis: A review of correct methodology. Theriogenology 2010, 73, 1167–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ben Kahla, I.; Boschiroli, M.L.; Souissi, F.; Cherif, N.; Benzarti, M.; Boukadida, J.; Hammami, S. Isolation and molecular characterisation of Mycobacterium bovis from raw milk in Tunisia. Afr. Health Sci. 2011, 11 (Suppl. 1), S2–S5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zumarraga, M.J.; Soutullo, A.; Garcia, M.I.; Marini, R.; Abdala, A.; Tarabla, H.; Echaide, S.; Lopez, M.; Zervini, E.; Canal, A.; et al. Detection of Mycobacterium bovis-infected dairy herds using PCR in bulk tank milk samples. Foodborne Pathog. Dis. 2012, 9, 132–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra, A.V.; Dos Reis, E.M.; Rodrigues, R.O.; Cenci, A.; Cerva, C.; Mayer, F.Q. Detection of Mycobacterium tuberculosis and Mycobacterium avium Complexes by Real-Time PCR in Bovine Milk from Brazilian Dairy Farms. J. Food Prot. 2015, 78, 1037–1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tao, Y.; Yun, J.; Wang, J.; Xu, P.; Li, C.; Liu, H.; Lan, Y.; Pan, J.; Du, W. High-performance detection of Mycobacterium bovis in milk using digital LAMP. Food Chem. 2020, 327, 126945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, A.B.; Floyd, S.; Gordon, S.V.; More, S.J. Prevalence of Mycobacterium bovis in milk on dairy cattle farms: An international systematic literature review and meta-analysis. Tuberc. Edinb. 2022, 132, 102166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollock, J.M.; Welsh, M.D.; McNair, J. Immune responses in bovine. tuberculosis: Towards new strategies for the diagnosis and control of disease. Vet. Immunol. Immunopathol. 2005, 108, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Name | Sequence (5′-3′) |

|---|---|

| MPB70-RPA-F1 MPB70-RPA-R1 | TGTCGGGCCAGCTCAATCCGCAAGTAAA GGATGCTGGTCAGCAGTGACGAATTGGTCTT |

| MPB70-RPA-F2 MPB70-RPA-R2 | CTGCTGACCAGCATCCTGACCTACCACGTA CGCCGGAGGCATTAGCACGCTGTCAATCA |

| MPB70-RPA-F3 MPB70-RPA-R3 | ACGGCTGCACTGTCGGGCCAGCTCAATC GGTGCCGACGACGTTGGCCGGGCTGGTTT |

| MPB70-RPA-F4 MPB70-RPA-R4 | CAGGACCCGGTCGCGGTGGCGGCCTCGAACAAT GGTCAGGATGCTGGTCAGCAGTGACGAATT |

| MPB70-RPA-F5 MPB70-RPA-R5 | AGCTCAATCCGCAAGTAAACCTGGTGGACA CCACTACGTGGTAGGTCAGGATGCTGGTCA |

| MPB70-RPA-F6 MPB70-RPA-R6 | AGCTCAAGACCAATTCGTCACTGCTGACCAG ATTAGCACGCTGTCAATCATGTACACCGTCG |

| crRNA1345 | AACACCGTGTACTGACCGCTGTTGAGGG |

| crRNA26 | GGCGTTACCGACCTTGAGGCTGTTACCC |

| Primer Name | Peak Fragment Size (bp) | Theoretical Fragment Size (bp) | Product Concentration (ng/µL) |

|---|---|---|---|

| MPB70 Primer1 | 159 | 154 | 2.82 |

| MPB70 Primer2 | 223 | 213 | 3.91 |

| MPB70 Primer3 | 224 | 217 | 1.99 |

| MPB70 Primer4 | 239 | 219 | 2.3 |

| MPB70 Primer5 | 171 | 162 | 1.08 |

| MPB70 Primer6 | 238 | 223 | 1.42 |

| RPA–CRISPR–Cas13a–LFD | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +ve | −ve | |||

| ELISA | +ve | 59 | 8 | 67 |

| −ve | 21 | 26 | 47 | |

| Total | 80 | 34 | 114 | |

| Kappa (95%CI) | 0.452 (95%CI: 0.287–0.617) | |||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Wang, J.; Wang, N.; Xu, L.; Zeng, X.; Cheng, J.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Yin, D.; Gou, J.; Pan, X.; et al. High-Performance Detection of Mycobacterium bovis in Milk Using Recombinase-Aided Amplification–Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat–Cas13a–Lateral Flow Detection. Foods 2024, 13, 1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13111601

Wang J, Wang N, Xu L, Zeng X, Cheng J, Zhang X, Zhang Y, Yin D, Gou J, Pan X, et al. High-Performance Detection of Mycobacterium bovis in Milk Using Recombinase-Aided Amplification–Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat–Cas13a–Lateral Flow Detection. Foods. 2024; 13(11):1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13111601

Chicago/Turabian StyleWang, Jieru, Nan Wang, Lei Xu, Xiaoyu Zeng, Junsheng Cheng, Xiaoqian Zhang, Yinghui Zhang, Dongdong Yin, Jiaojiao Gou, Xiaocheng Pan, and et al. 2024. "High-Performance Detection of Mycobacterium bovis in Milk Using Recombinase-Aided Amplification–Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeat–Cas13a–Lateral Flow Detection" Foods 13, no. 11: 1601. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13111601