Sensing the Snacking Experience: Bodily Sensations Linked to the Consumption of Healthy and Unhealthy Snack Foods—A Comparison between Body Mass Index Levels

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Respondents and Recruitment

2.3. Questionnaire

2.4. Statistical Analyses

3. Results

3.1. Sociodemographic and Lifestyle Characteristics of the Three BMI Groups

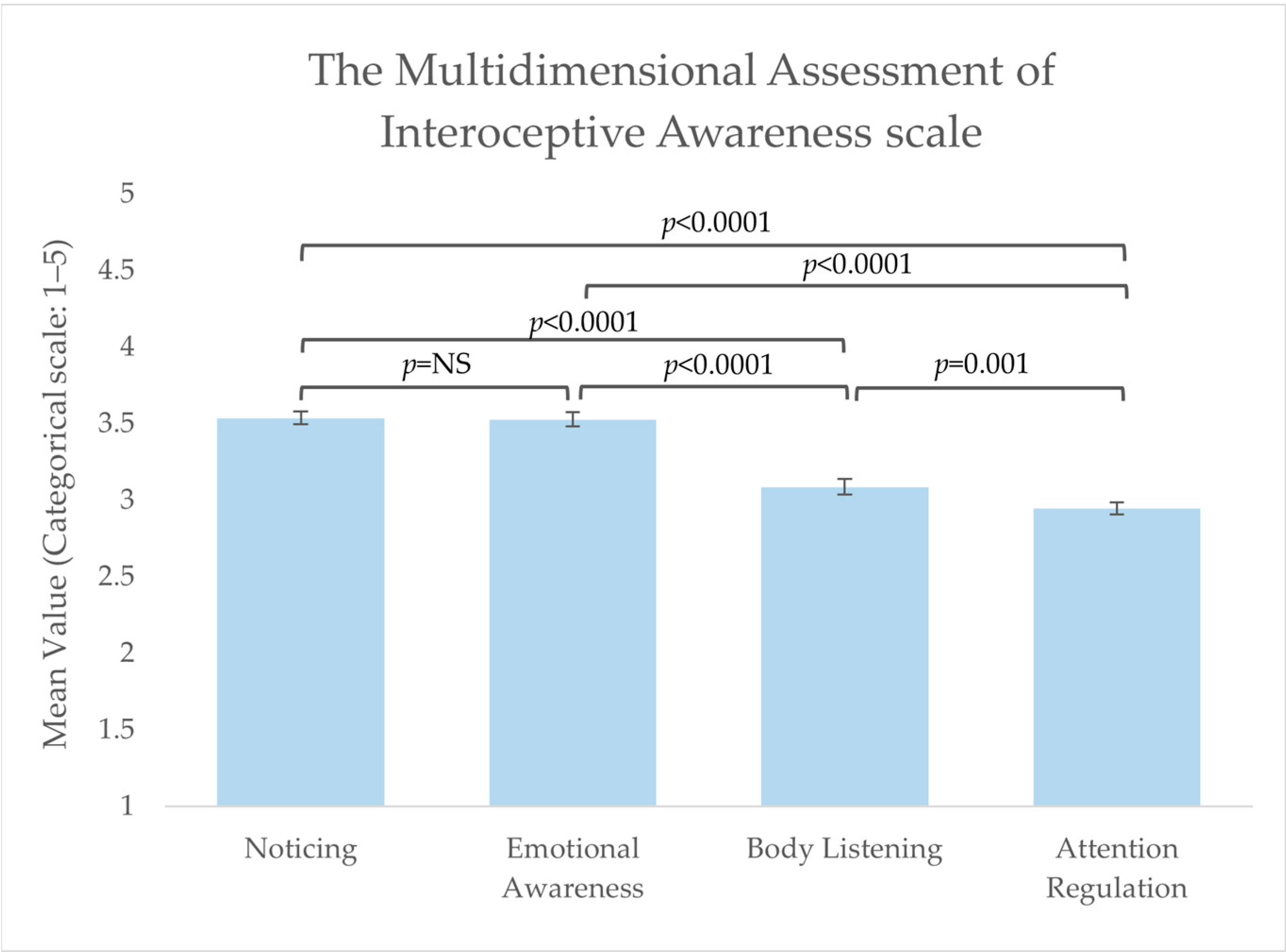

3.2. Interoceptive Capabilities including Pleasure Sensations

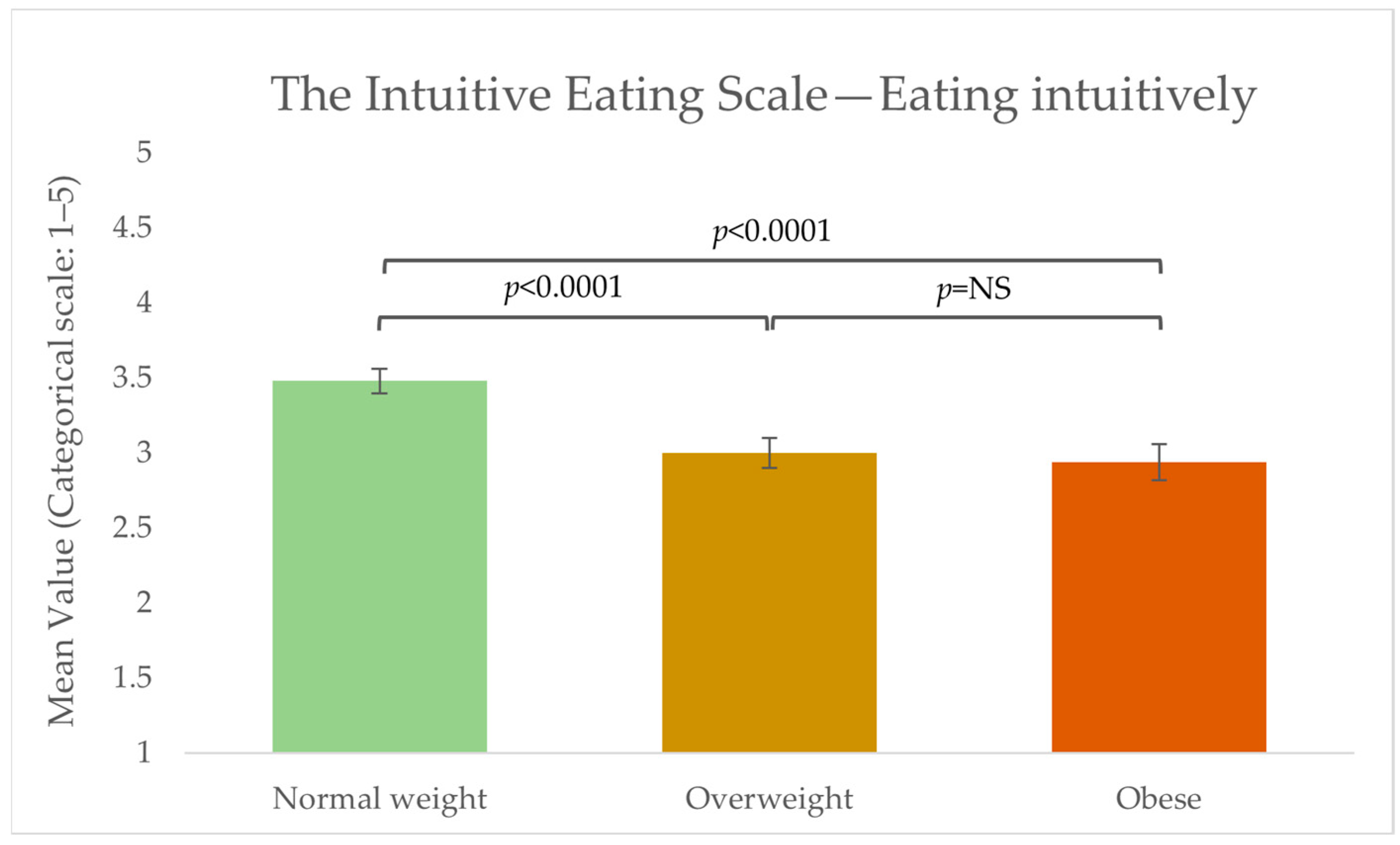

3.3. Intuitive Eating

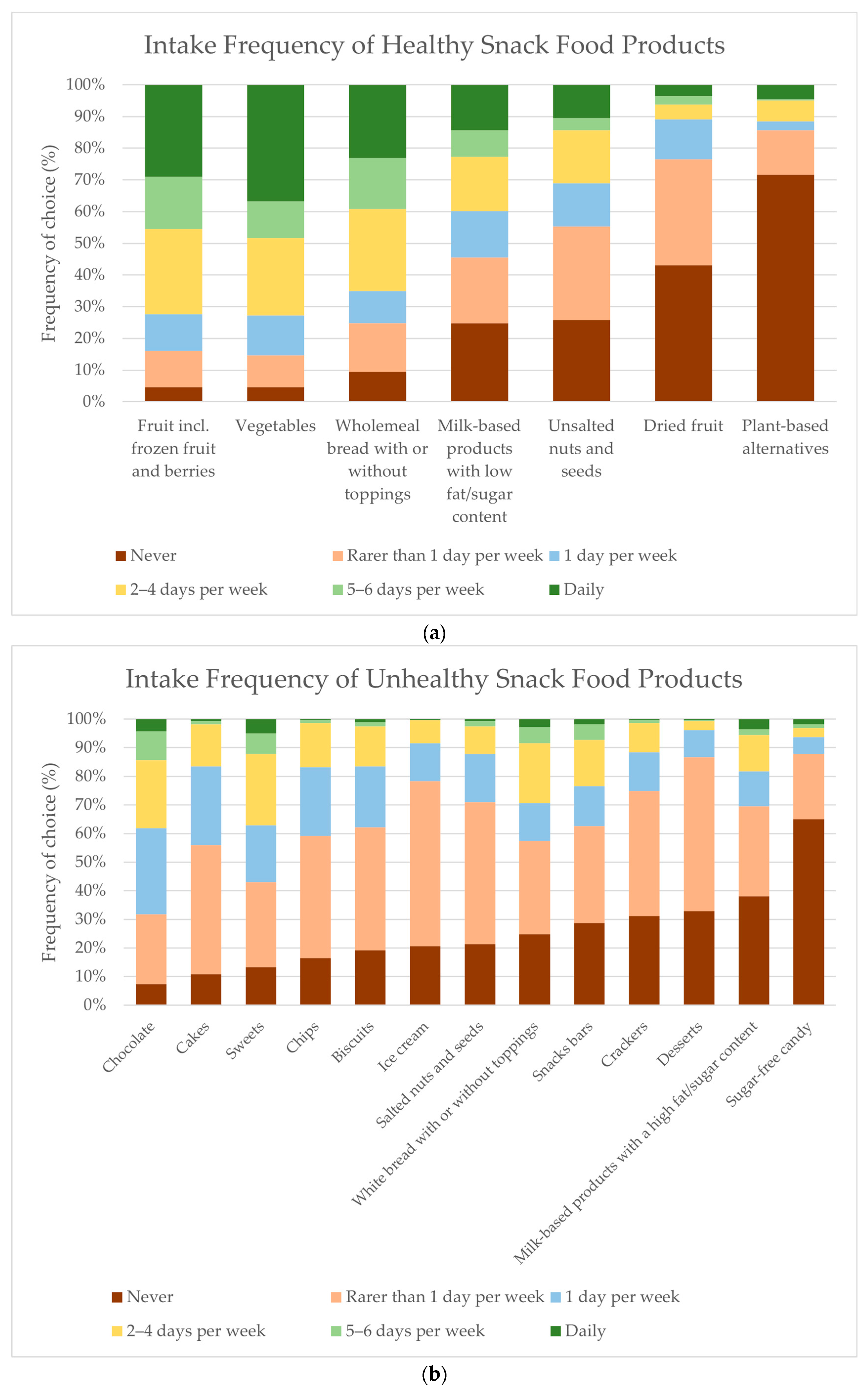

3.4. Frequency of Snack Food Consumption

3.5. Drivers of Snack Food Consumption

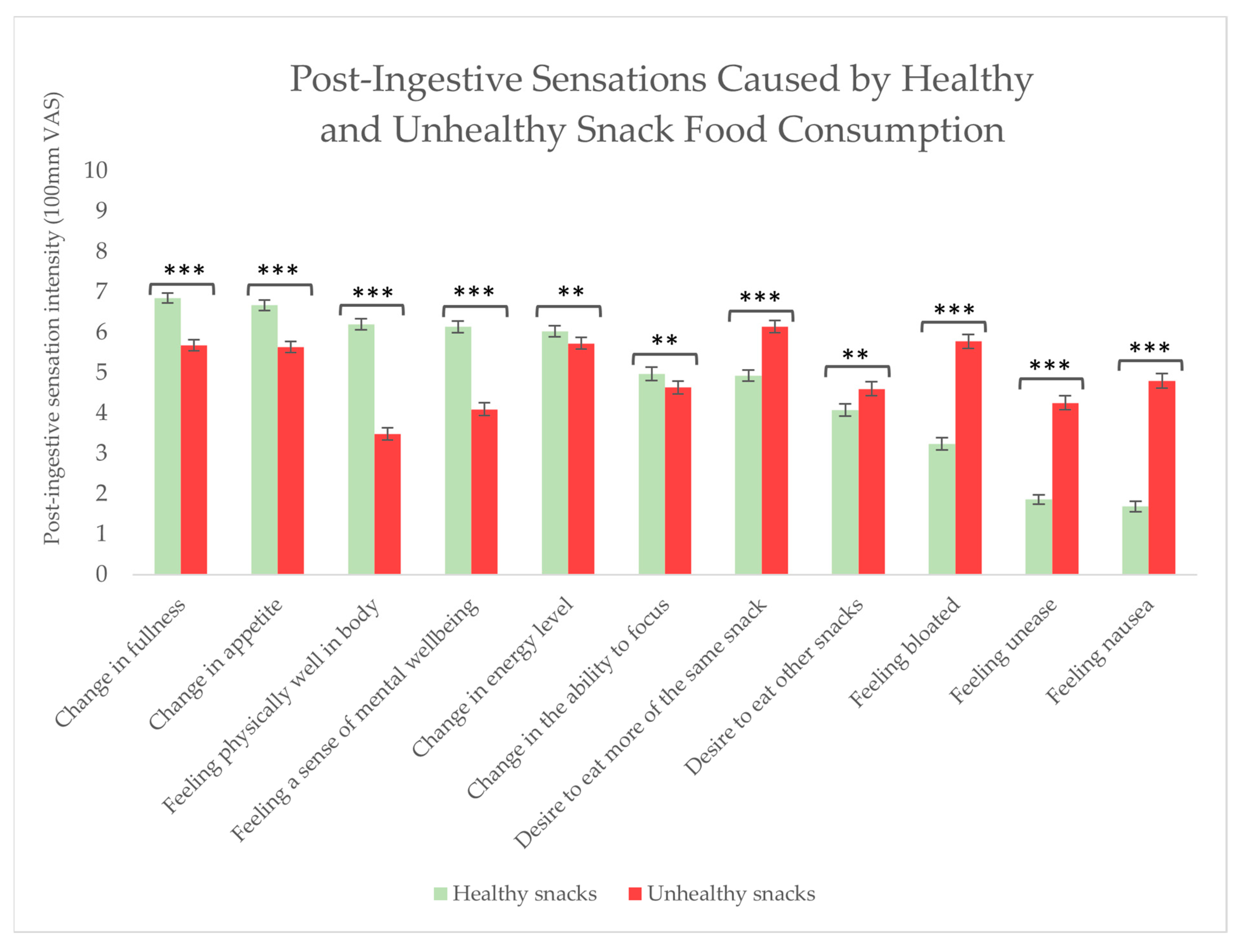

3.6. Post-Ingestive Sensations Caused by Snack Food Consumption

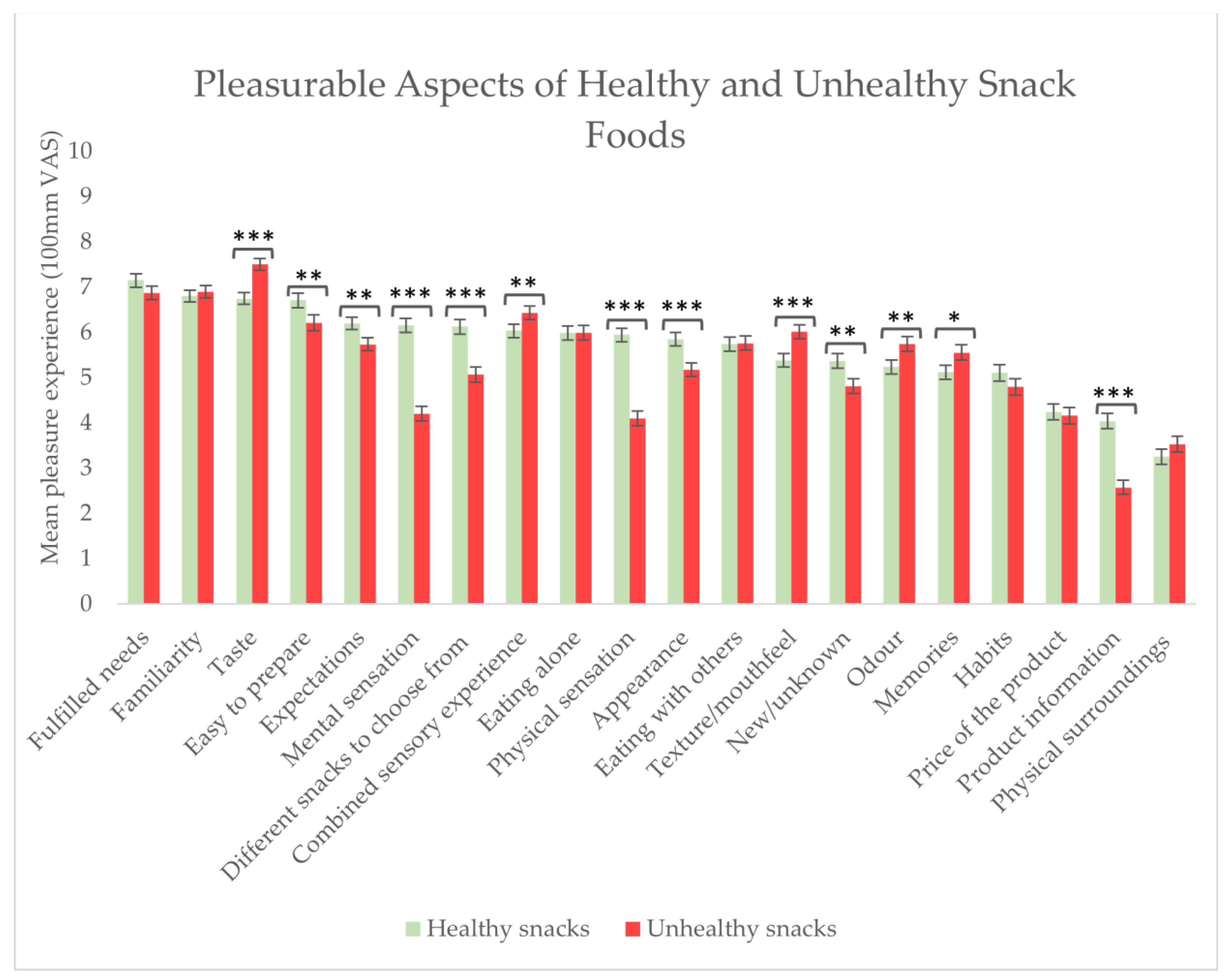

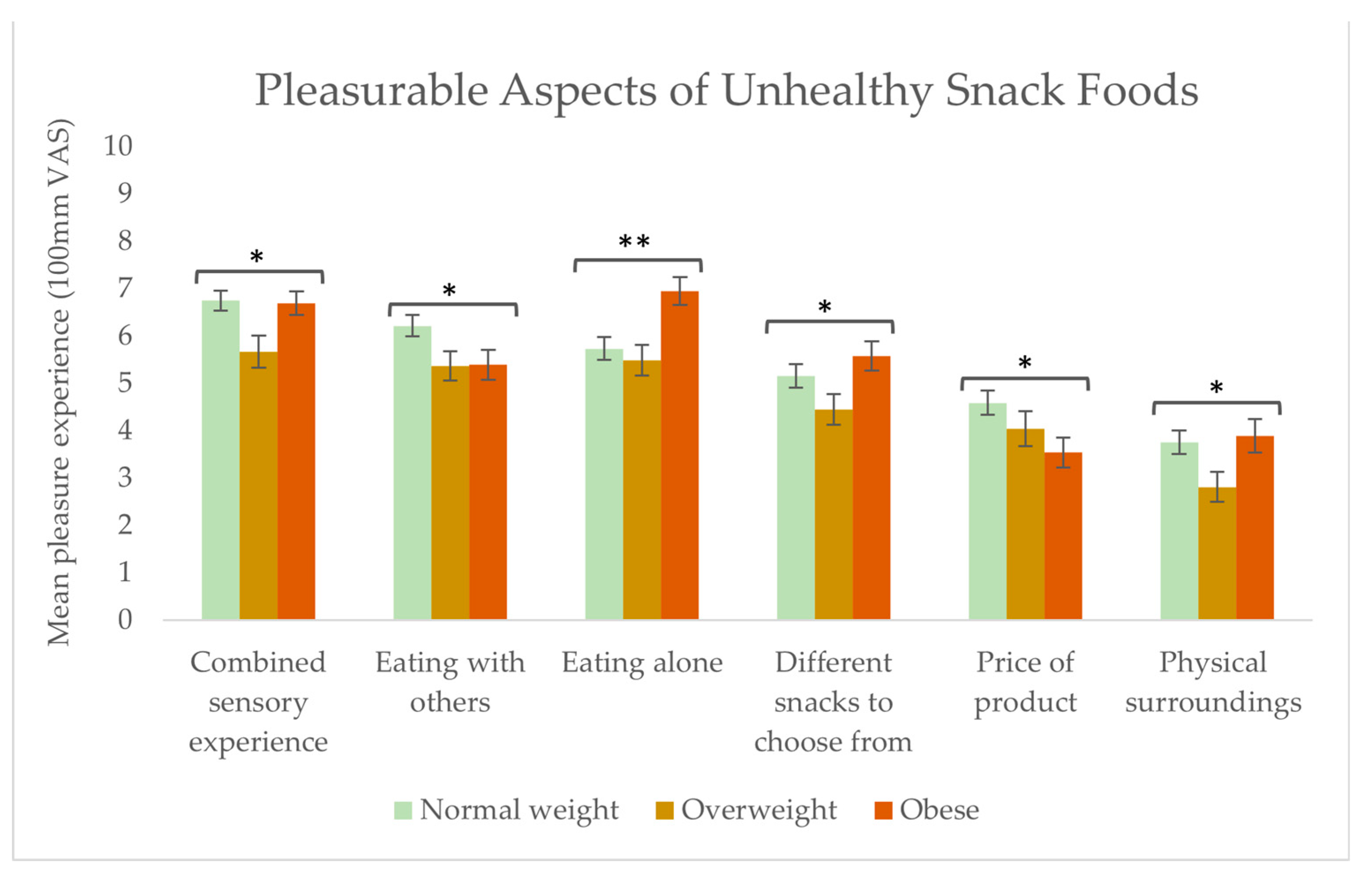

3.7. Pleasurable Aspects of Healthy and Unhealthy Snack Foods

4. Discussion

4.1. Interoceptive Capabilities and Intuitive Eating

4.2. Snack Food Consumption and Drivers of Snack Intake

4.3. Post-Ingestive Sensations after Snack Food Consumption

4.4. Pleasurable Aspects of Healthy and Unhealthy Snack Foods

4.5. Strengths and Limitations of the Current Study

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Controlling the Global Obesity Epidemic. Available online: https://www.who.int/activities/controlling-the-global-obesity-epidemic (accessed on 6 July 2023).

- Mann, T.; Tomiyama, A.J.; Westling, E.; Lew, A.-M.; Samuels, B.; Chatman, J. Medicare’s Search for Effective Obesity Treatments: Diets Are Not the Answer. Am. Psychol. 2007, 62, 220–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weltens, N.; Zhao, D.; Van Oudenhove, L. Where Is the Comfort in Comfort Foods? Mechanisms Linking Fat Signaling, Reward, and Emotion. Neurogastroenterol. Motil. 2014, 26, 303–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palazzo, C.C.; Leghi, B.E.; Diez-Garcia, R.W. Food Consciousness Intervention Improves Interoceptive Sensitivity and Expression of Exteroception in Women. Nutrients 2022, 14, 450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clifford, D.; Ozier, A.; Bundros, J.; Moore, J.; Kreiser, A.; Morris, M.N. Impact of Non-Diet Approaches on Attitudes, Behaviors, and Health Outcomes: A Systematic Review. J. Nutr. Educ. Behav. 2015, 47, 143–155.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruyter, J.C.; Olthof, M.R.; Seidell, J.C.; Katan, M.B. A Trial of Sugar-Free or Sugar-Sweetened Beverages and Body Weight in Children. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012, 367, 1397–1406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Ruyter, J.C.; Katan, M.B.; Kuijper, L.D.J.; Liem, D.G.; Olthof, M.R. The Effect of Sugar-Free Versus Sugar-Sweetened Beverages on Satiety, Liking and Wanting: An 18 Month Randomized Double-Blind Trial in Children. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duerlund, M.; Andersen, B.V.; Grønbeck, M.S.; Byrne, D.V. Consumer Reflections on Post-Ingestive Sensations. A Qualitative Approach by Means of Focus Group Interviews. Appetite 2019, 142, 104350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duerlund, M.; Vad Andersen, B.; Victor Byrne, D. Dynamic Changes in Post-Ingestive Sensations after Consumption of a Breakfast Meal High in Protein or Carbohydrate. Foods 2019, 8, 413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simmons, W.K.; DeVille, D.C. Interoceptive Contributions to Healthy Eating and Obesity. Curr. Opin. Psychol. 2017, 17, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andersen, B.V.; Chan, R.C.K.; Byrne, D.V. A Conceptual Framework for Multi-Dimensional Measurements of Food Related Pleasure—The Food Pleasure Scale. Foods 2021, 10, 2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brondel, L.; Quilliot, D.; Mouillot, T.; Khan, N.A.; Bastable, P.; Boggio, V.; Leloup, C.; Pénicaud, L. Taste of Fat and Obesity: Different Hypotheses and Our Point of View. Nutrients 2022, 14, 555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Graaf, C. Sensory Responses, Food Intake and Obesity. In Food, Diet and Obesity; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2005; pp. 137–159. ISBN 978-1-85573-958-1. [Google Scholar]

- Stevenson, R.J.; Mahmut, M.; Rooney, K. Individual Differences in the Interoceptive States of Hunger, Fullness and Thirst. Appetite 2015, 95, 44–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, B.M.; Pollatos, O. The Relevance of Interoception for Eating Behavior and Eating Disorders; Oxford University Press: Oxford UK, 2018; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson, P.M.; Taylor, L.; Laws, K.R. Self-Reported Interoceptive Deficits in Eating Disorders: A Meta-Analysis of Studies Using the Eating Disorder Inventory. J. Psychosom. Res. 2018, 110, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.; Foote, G.; Smith, J.; Higgs, S.; Jones, A. Interoception and Obesity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of the Relationship between Interoception and BMI. Int. J. Obes. 2021, 45, 2515–2526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sobik, L.; Hutchison, K.; Craighead, L. Cue-Elicited Craving for Food: A Fresh Approach to the Study of Binge Eating. Appetite 2005, 44, 253–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herbert, B.M.; Blechert, J.; Hautzinger, M.; Matthias, E.; Herbert, C. Intuitive Eating Is Associated with Interoceptive Sensitivity. Effects on Body Mass Index. Appetite 2013, 70, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finlayson, G.; King, N.; Blundell, J.E. Liking vs. Wanting Food: Importance for Human Appetite Control and Weight Regulation. Neurosci. Biobehav. Rev. 2007, 31, 987–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Havermans, R.C.; Janssen, T.; Giesen, J.C.A.H.; Roefs, A.; Jansen, A. Food Liking, Food Wanting, and Sensory-Specific Satiety. Appetite 2009, 52, 222–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mela, D.J. Eating for Pleasure or Just Wanting to Eat? Reconsidering Sensory Hedonic Responses as a Driver of Obesity. Appetite 2006, 47, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljefree, N.M.; Shatwan, I.M.; Almoraie, N.M. Impact of the Intake of Snacks and Lifestyle Behaviors on Obesity among University Students Living in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Healthcare 2022, 10, 400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattes, R.D. Snacking: A Cause for Concern. Physiol. Behav. 2018, 193, 279–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Njike, V.Y.; Smith, T.M.; Shuval, O.; Shuval, K.; Edshteyn, I.; Kalantari, V.; Yaroch, A.L. Snack Food, Satiety, and Weight. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 866–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cleobury, L.; Tapper, K. Reasons for Eating ‘Unhealthy’ Snacks in Overweight and Obese Males and Females. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 27, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verhoeven, A.A.C.; Adriaanse, M.A.; de Vet, E.; Fennis, B.M.; de Ridder, D.T.D. It’s My Party and I Eat If I Want to. Reasons for Unhealthy Snacking. Appetite 2015, 84, 20–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Compusense—Consumer and Sensory Testing Made Simple. Available online: https://compusense.com/ (accessed on 29 June 2023).

- Indenrigs-og Sundhedsministeriet. Bekendtgørelse Af Lov Om Videnskabsetisk Behandling Af Sundhedsvidenskabelige Forskningsprojekter; Indenrigs-og Sundhedsministeriet: Copenhagen, Danmark, 2017; Vol. LBK nr 1338 af 01/09/2020. [Google Scholar]

- Mehling, W.E.; Acree, M.; Stewart, A.; Silas, J.; Jones, A. The Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness, Version 2 (MAIA-2). PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0208034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Multidimensional Assessment of Interoceptive Awareness. Available online: https://osher.ucsf.edu/research/maia (accessed on 17 April 2023).

- Snaith, R.P.; Hamilton, M.; Morley, S.; Humayan, A.; Hargreaves, D.; Trigwell, P. A Scale for the Assessment of Hedonic Tone the Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale. Br. J. Psychiatry 1995, 167, 99–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franken, I.H.A.; Rassin, E.; Muris, P. The Assessment of Anhedonia in Clinical and Non-Clinical Populations: Further Validation of the Snaith–Hamilton Pleasure Scale (SHAPS). J. Affect. Disord. 2007, 99, 83–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rizvi, S.J.; Quilty, L.C.; Sproule, B.A.; Cyriac, A.; Michael Bagby, R.; Kennedy, S.H. Development and Validation of the Dimensional Anhedonia Rating Scale (DARS) in a Community Sample and Individuals with Major Depression. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 229, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tylka, T.L. Development and Psychometric Evaluation of a Measure of Intuitive Eating. J. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 53, 226–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camilleri, G.M.; Méjean, C.; Bellisle, F.; Andreeva, V.A.; Sautron, V.; Hercberg, S.; Péneau, S. Cross-Cultural Validity of the Intuitive Eating Scale-2. Psychometric Evaluation in a Sample of the General French Population. Appetite 2015, 84, 34–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biltoft-Jensen, A.; Biltoft-Jensen, K.; Christensen, T.; Matthiessen, J. Råderummet Til Tomme Kalorier Og En Ernæringsprofileringsmodel Til at Klassificere Næringsfattige Og Energitætte Fødevarer; Ministeriet for Fødevarer, Landbrug og Fiskeri, Fødevarestyrelsen: DTU, Fødevareinstituttet: Kemitorvet, Danmark, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- De Cock, N.; Van Camp, J.; Kolsteren, P.; Lachat, C.; Huybregts, L.; Maes, L.; Deforche, B.; Verstraeten, R.; Vangeel, J.; Beullens, K.; et al. Development and Validation of a Quantitative Snack and Beverage Food Frequency Questionnaire for Adolescents. J. Hum. Nutr. Diet. 2017, 30, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Biltoft-Jensen, A.; Matthiessen, J.; Hess Ygil, K.; Christensen, T. Defining Energy-Dense, Nutrient-Poor Food and Drinks and Estimating the Amount of Discretionary Energy. Nutrients 2022, 14, 1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hess, J.M.; Jonnalagadda, S.S.; Slavin, J.L. What Is a Snack, Why Do We Snack, and How Can We Choose Better Snacks? A Review of the Definitions of Snacking, Motivations to Snack, Contributions to Dietary Intake, and Recommendations for Improvement. Adv. Nutr. 2016, 7, 466–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, E.; Marty, L.; Higgs, S.; Jones, A. Interoception, Eating Behaviour and Body Weight. Physiol. Behav. 2021, 237, 113434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, J.; Brewer, R.; Plans, D.; Khalsa, S.S.; Catmur, C.; Bird, G. Testing the Independence of Self-Reported Interoceptive Accuracy and Attention. Q. J. Exp. Psychol. 2020, 73, 115–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Herbert, B.M. Interoception and Its Role for Eating, Obesity, and Eating Disorders: Empirical Findings and Conceptual Conclusions. Eur. J. Health Psychol. 2020, 27, 188–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaefer, J.T.; Magnuson, A.B. A Review of Interventions That Promote Eating by Internal Cues. J. Acad. Nutr. Diet. 2014, 114, 734–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mata, F.; Verdejo-Roman, J.; Soriano-Mas, C.; Verdejo-Garcia, A. Insula Tuning towards External Eating versus Interoceptive Input in Adolescents with Overweight and Obesity. Appetite 2015, 93, 24–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, H.A.; Williams, C.; Pink, A.E.; Freegard, G.; Owens, A.; Benton, D. Getting to the Heart of the Matter: Does Aberrant Interoceptive Processing Contribute towards Emotional Eating? PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0186312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fadnes, L. Taube How to Identify Information Bias Due to Self-Reporting in Epidemiological Research. Internet J. Epidemiol. 2009, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsakiris, M.; Critchley, H. Interoception beyond Homeostasis: Affect, Cognition and Mental Health. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2016, 371, 20160002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Strien, T.; Frijters, J.E.R.; Bergers, G.P.A.; Defares, P.B. The Dutch Eating Behavior Questionnaire (DEBQ) for Assessment of Restrained, Emotional, and External Eating Behavior. Int. J. Eat. Disord. 1986, 5, 295–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazarevich, I.; Irigoyen Camacho, M.E.; Velázquez-Alva, M.D.C.; Zepeda Zepeda, M. Relationship among Obesity, Depression, and Emotional Eating in Young Adults. Appetite 2016, 107, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bullock, A.J.; Goldbacher, E.M. Interoceptive Awareness and Emotional Eating in College Women: The Role of Appetite and Emotional Awareness. J. Am. Coll. Health 2021, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, C. Comfort Food: A Review. Int. J. Gastron. Food Sci. 2017, 9, 105–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Attuquayefio, T.; Stevenson, R.J.; Boakes, R.A.; Oaten, M.J.; Yeomans, M.R.; Mahmut, M.; Francis, H.M. A High-Fat High-Sugar Diet Predicts Poorer Hippocampal-Related Memory and a Reduced Ability to Suppress Wanting under Satiety. J. Exp. Psychol. Anim. Learn. Cogn. 2016, 42, 415–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitropoulos, A.; Tkach, J.; Ho, A.; Kennedy, J. Greater Corticolimbic Activation to High-Calorie Food Cues after Eating in Obese vs. Normal-Weight Adults. Appetite 2012, 58, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davis, C.; Strachan, S.; Berkson, M. Sensitivity to Reward: Implications for Overeating and Overweight. Appetite 2004, 42, 131–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raghunathan, R.; Naylor, R.W.; Hoyer, W.D. The Unhealthy = Tasty Intuition and Its Effects on Taste Inferences, Enjoyment, and Choice of Food Products. J. Mark. 2006, 70, 170–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ueland, V. Stigmatisering og skam—En kvalitativ studie om å leve med fedme. Sykepl. Forsk. 2019, 14, e-77012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrory, M.A.; Fuss, P.J.; McCallum, J.E.; Yao, M.; Vinken, A.G.; Hays, N.P.; Roberts, S.B. Dietary Variety within Food Groups: Association with Energy Intake and Body Fatness in Men and Women. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 1999, 69, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raynor, H.A.; Epstein, L.H. Dietary Variety, Energy Regulation, and Obesity. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 127, 325–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brewer, R.; Cook, R.; Bird, G. Alexithymia: A General Deficit of Interoception. R. Soc. Open Sci. 2016, 3, 150664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Sample Characteristics | Total | Normal Weight | Overweight | Obese | p-Values |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Number of respondents | 286 (100%) | 130 (45.5%) | 80 (28%) | 76 (26.5%) | α ≤ 0.05 |

| Gender | p = 0.001 | ||||

| Female | 240 (84.2%) | 117 (90%) | 56 (70.9%) | 67 (88.2%) | |

| Male | 45 (15.8%) | 13 (10%) | 23 (29.9%) | 9 (11.8%) | |

| Age * | 37.94 (±14.54) | 34.23 (± 13.23) | 40.82 (±15.62) | 41.26 (±13.86) | p < 0.0001 |

| BMI 1,* | 27.24 (±6.40) | 22.14 (±1.89) | 27.26 (±1.35) | 35.95 (±5.08) | p < 0.0001 |

| Highest completed educational level | p = 0.001 | ||||

| Primary school/elementary school education | 16 (5.6%) | 6 (4.6%) | 3 (3.9%) | 7 (9.2%) | |

| Secondary/high school education | 34 (11.9%) | 22 (16.9%) | 10 (12.7%) | 2 (2.6%) | |

| Vocational education | 32 (11.2%) | 5 (3.8%) | 13 (16.5%) | 14 (18.4%) | |

| Short higher education (2 years) | 19 (6.7%) | 4 (3.1%) | 6 (7.6%) | 9 (11.8%) | |

| Medium-length higher education (3–4 years) | 101 (35.4%) | 50 (38.5%) | 26 (32.9%) | 25 (32.9%) | |

| Long higher education (5+ years) | 83 (29.1%) | 43 (33.1%) | 21 (26.6%) | 19 (25%) | |

| Smoking status | NS | ||||

| Frequent smoker | 27 (9.5%) | 9 (6.9%) | 8 (10.1%) | 10 (13.2%) | |

| Occasional smoker | 225 (78.9) | 107 (82.3%) | 57 (72.2%) | 61 (80.3%) | |

| Non-smoker | 33 (11.6%) | 14 (10.8%) | 14 (17.7%) | 5 (6.6%) | |

| Weight gain (5+ kg within the last six months) | NS | ||||

| Weight not stable | 78 (27.3%) | 27 (20.8%) | 26 (32.5%) | 25 (32.9%) | |

| Weight stable | 208 (72.7%) | 103 (79.2%) | 54 (67.5%) | 51 (67.1%) | |

| Weight loss (5+ kg within the last six months) | p = 0.004 | ||||

| Weight not stable | 90 (31.5%) | 28 (21.5%) | 32 (40%) | 30 (39.5%) | |

| Weight stable | 196 (68.5%) | 102 (78.5%) | 48 (60%) | 46 (60.5%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Frederiksen, C.; Byrne, D.V.; Andersen, B.V. Sensing the Snacking Experience: Bodily Sensations Linked to the Consumption of Healthy and Unhealthy Snack Foods—A Comparison between Body Mass Index Levels. Foods 2024, 13, 438. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13030438

Frederiksen C, Byrne DV, Andersen BV. Sensing the Snacking Experience: Bodily Sensations Linked to the Consumption of Healthy and Unhealthy Snack Foods—A Comparison between Body Mass Index Levels. Foods. 2024; 13(3):438. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13030438

Chicago/Turabian StyleFrederiksen, Chanette, Derek Victor Byrne, and Barbara Vad Andersen. 2024. "Sensing the Snacking Experience: Bodily Sensations Linked to the Consumption of Healthy and Unhealthy Snack Foods—A Comparison between Body Mass Index Levels" Foods 13, no. 3: 438. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13030438

APA StyleFrederiksen, C., Byrne, D. V., & Andersen, B. V. (2024). Sensing the Snacking Experience: Bodily Sensations Linked to the Consumption of Healthy and Unhealthy Snack Foods—A Comparison between Body Mass Index Levels. Foods, 13(3), 438. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods13030438