Comparison of the Potential of “Green” Classical and Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents in the Production of Natural Food Colorant Extracts from the Roots of Alkanna tinctoria (L.)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Materials

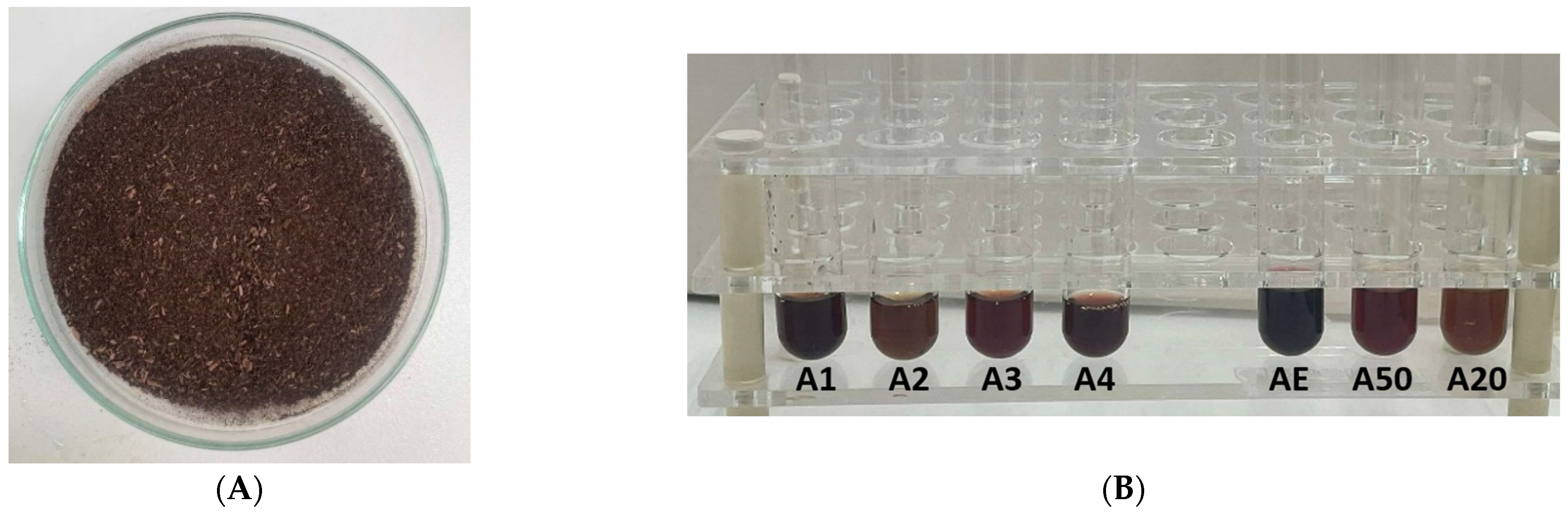

2.1.1. Biological Materials

2.1.2. Chemicals

2.2. Sampling and Extract Preparation

2.2.1. Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction Using Classical Solvents

2.2.2. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent (NADES) Extraction

2.3. Spectrophotometric Determination of the Radical Scavenging Activity

2.3.1. 2,2-Diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) Method

2.3.2. 2,2′-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic Acid (ABTS) Assay

2.3.3. Ferric-Reducing Antioxidant Power (FRAP) Assay

2.4. Determination of Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

2.5. Determination of Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

2.6. Determination of Total Condensed Tannin Content (TCT)

2.7. Determination of Total Anthocyanin Content (TAntC)

2.8. Determination of Total Alkaloid Content (TAlkC)

2.9. ATR-FTIR Spectroscopic Analyses

2.10. UV/Vis Spectrophotometry

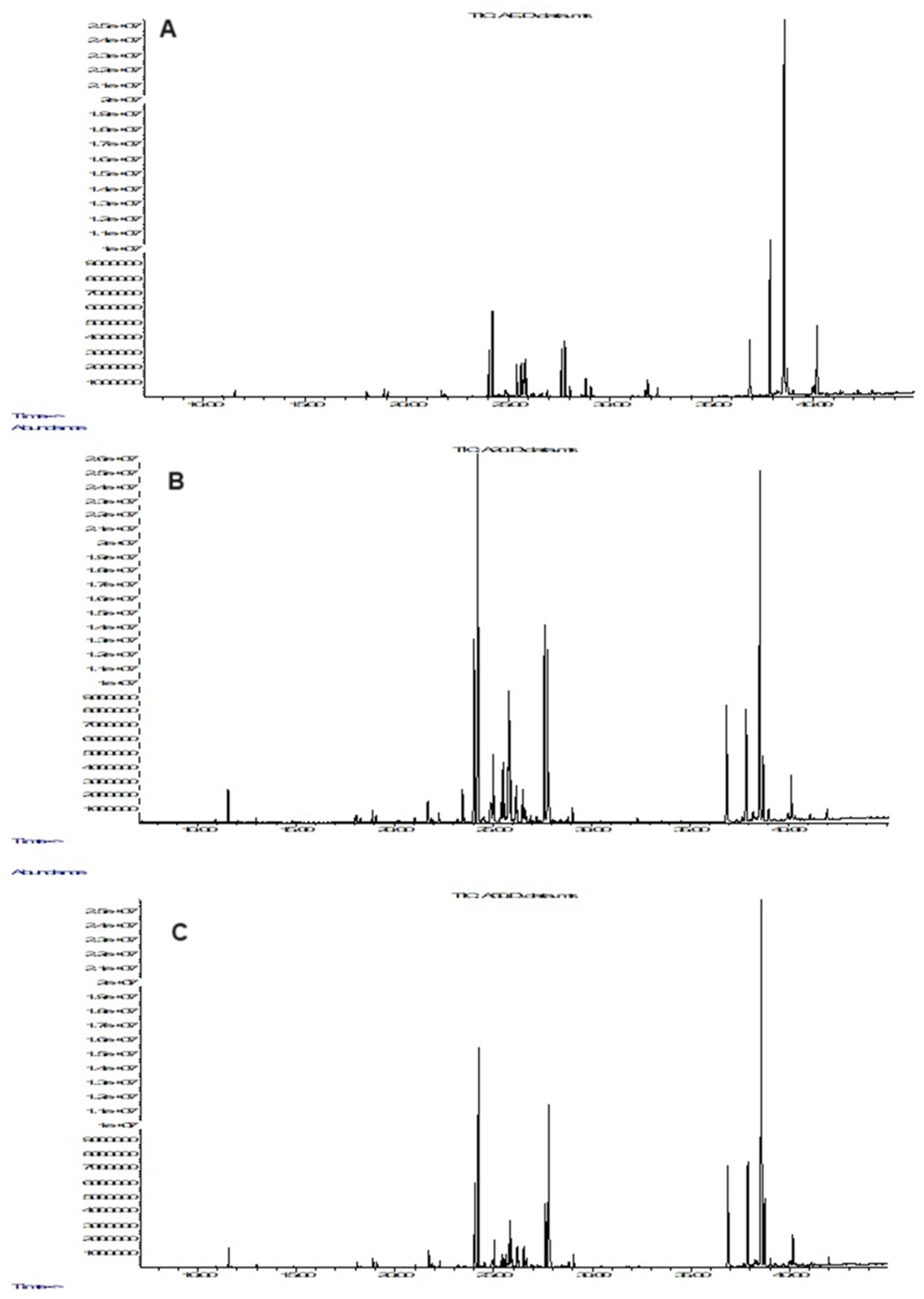

2.11. Identification of Bioactive Compounds via GC-MS Analysis

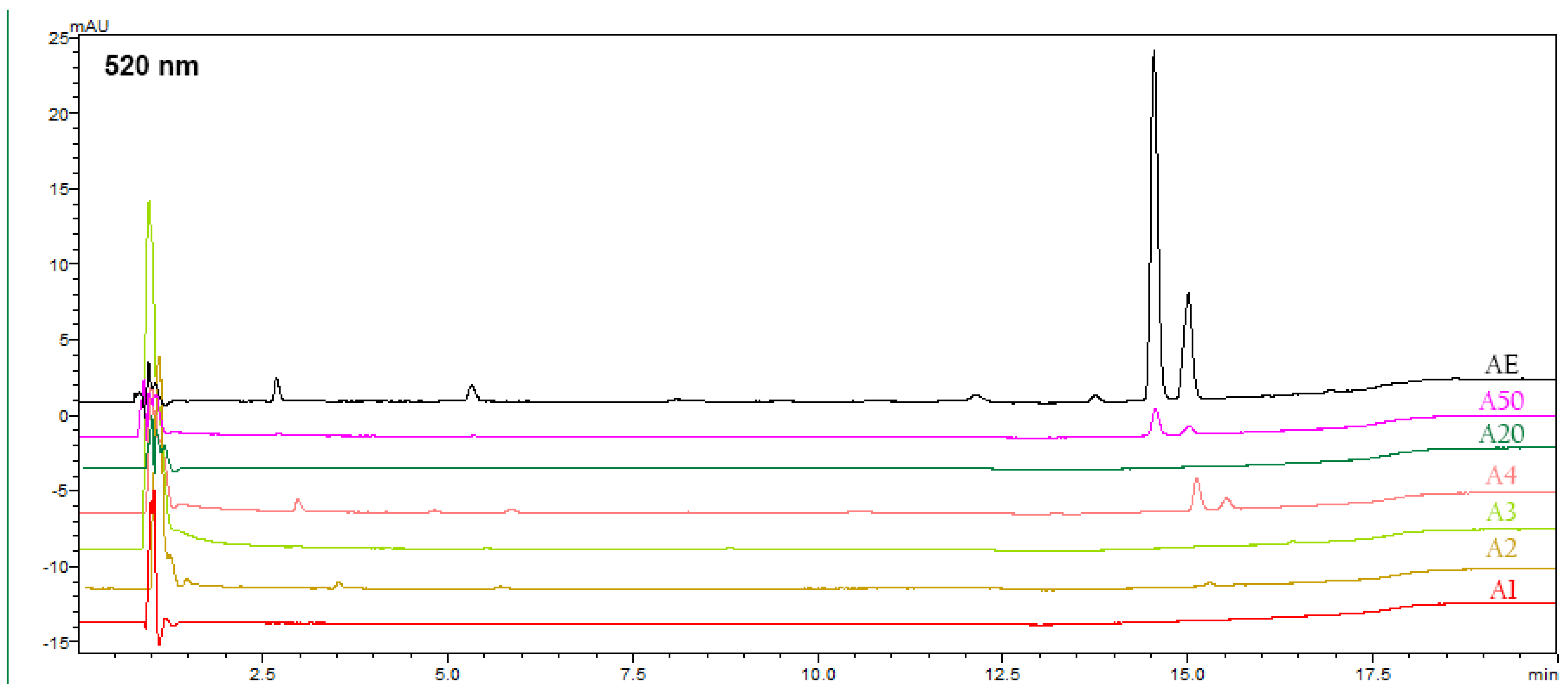

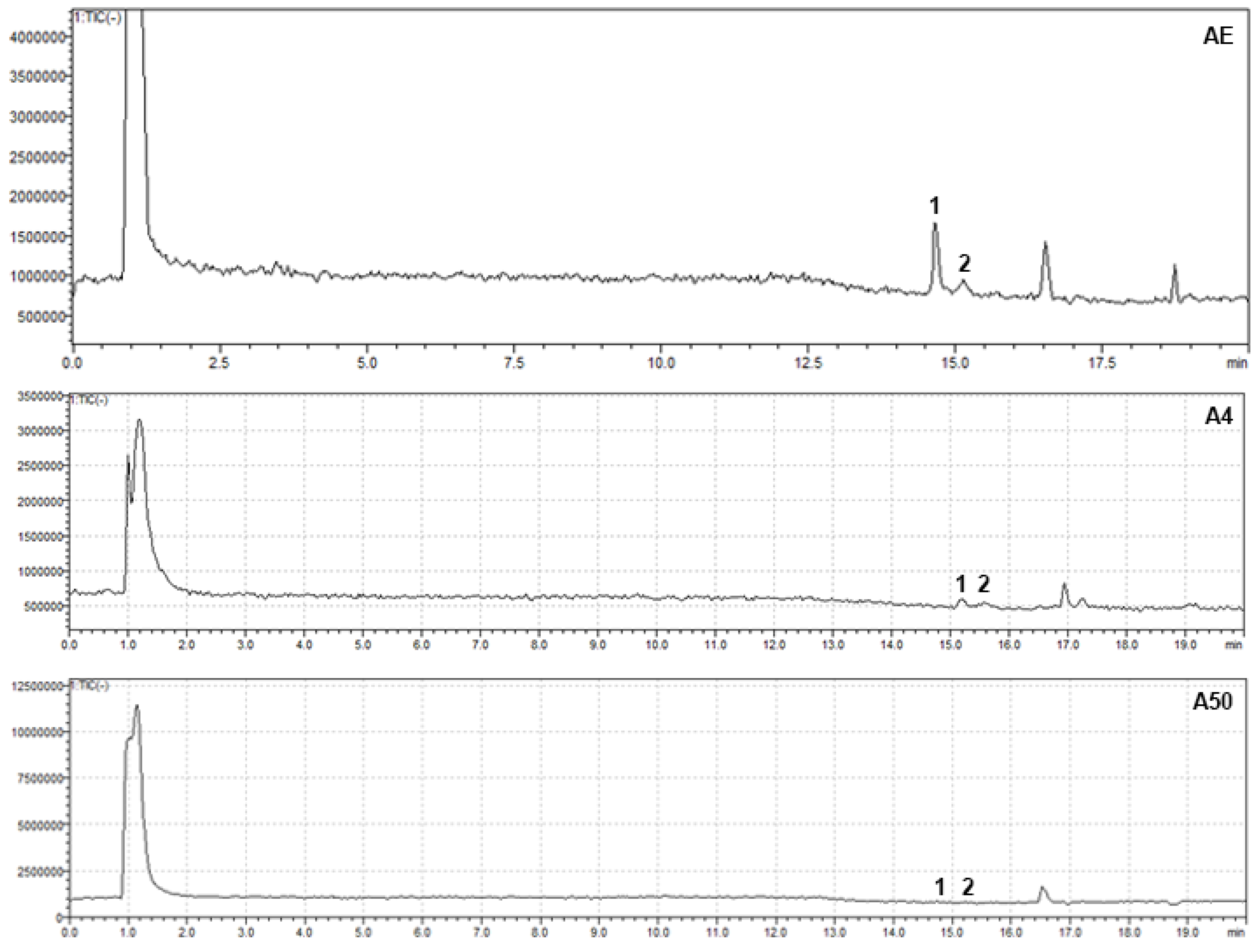

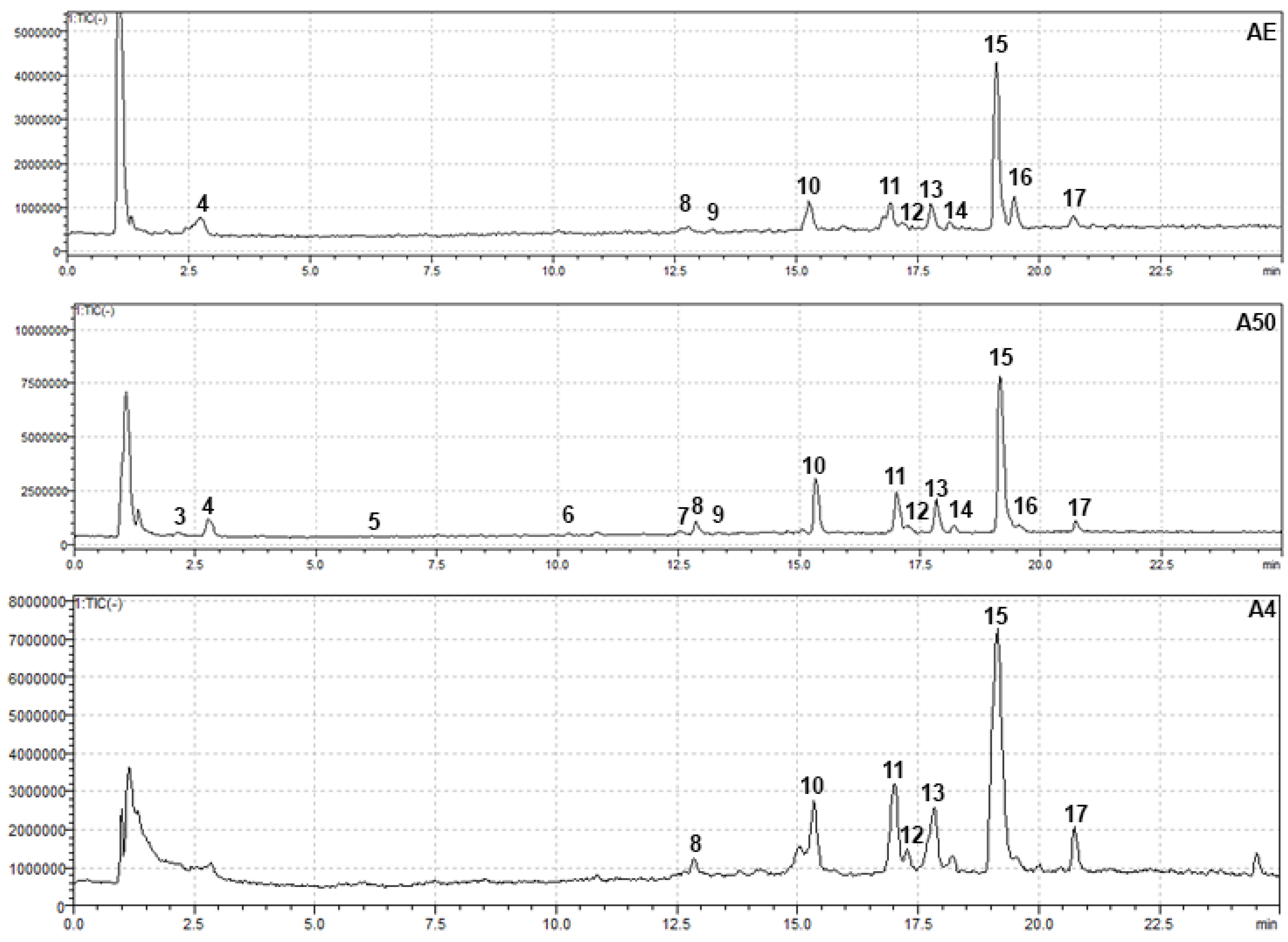

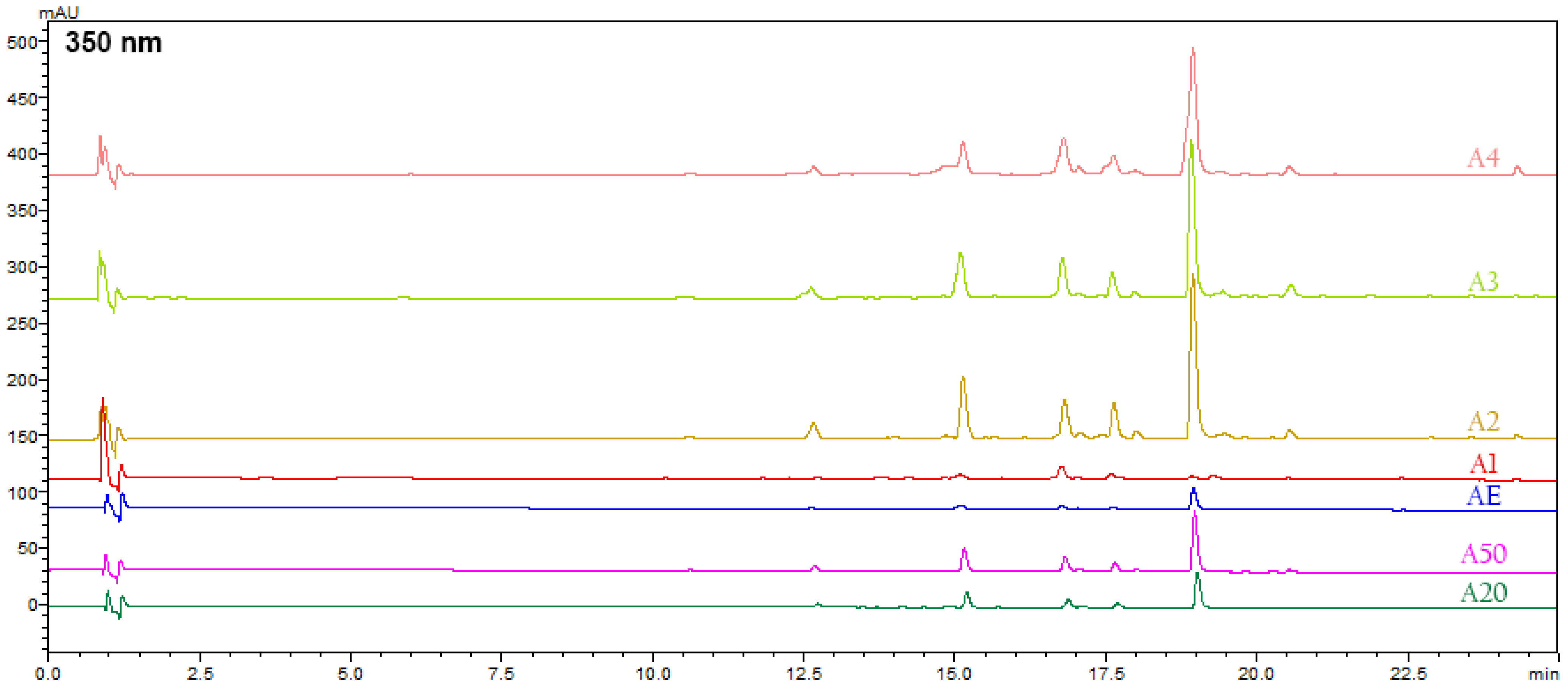

2.12. HPLC-PDA-MS Analysis

2.12.1. Identification of the Pigment Compounds—Alkannines (Method 1, M1)

2.12.2. Identification of Phenolic Compounds and Flavonoids (Method 2, M2)

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Contents of Biologically Active Compounds

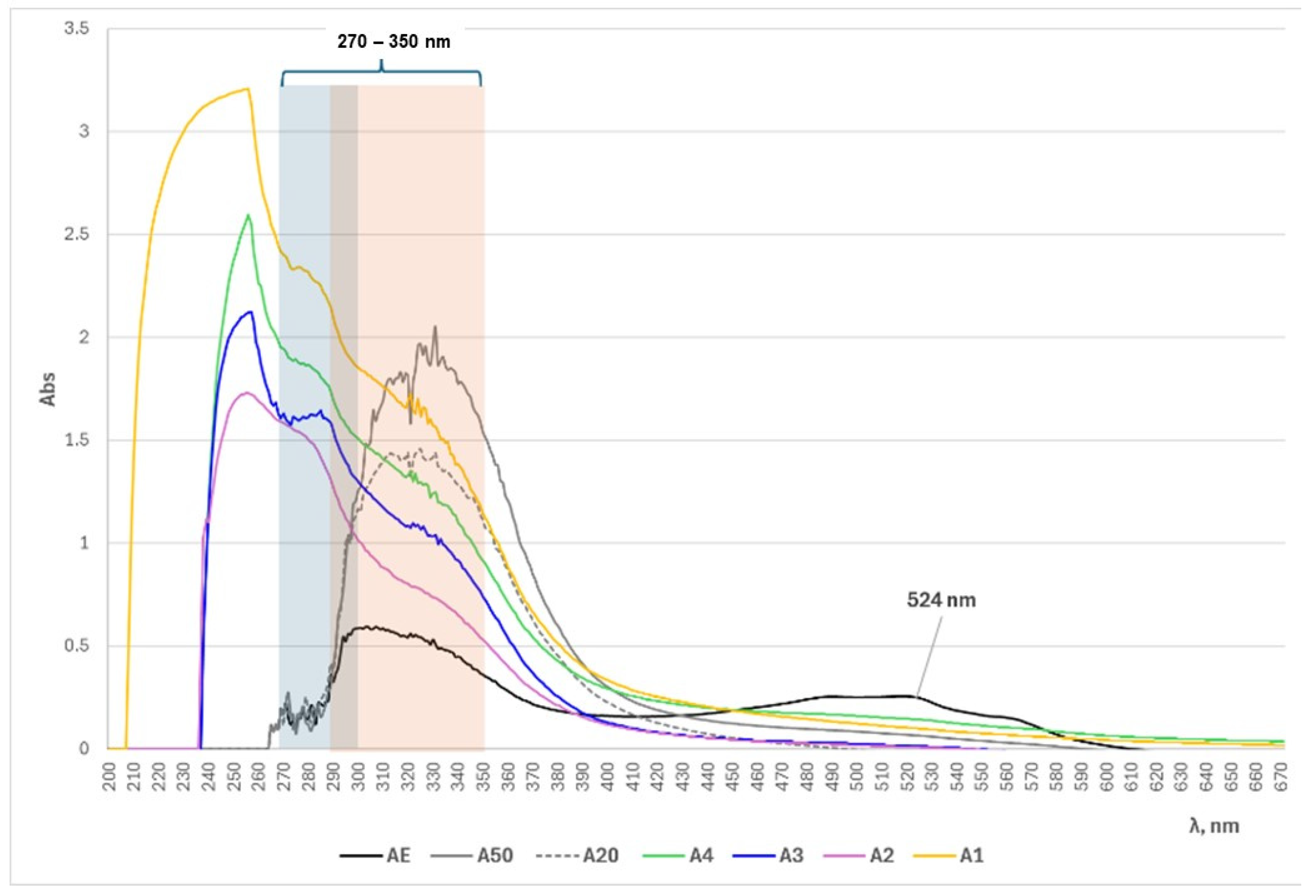

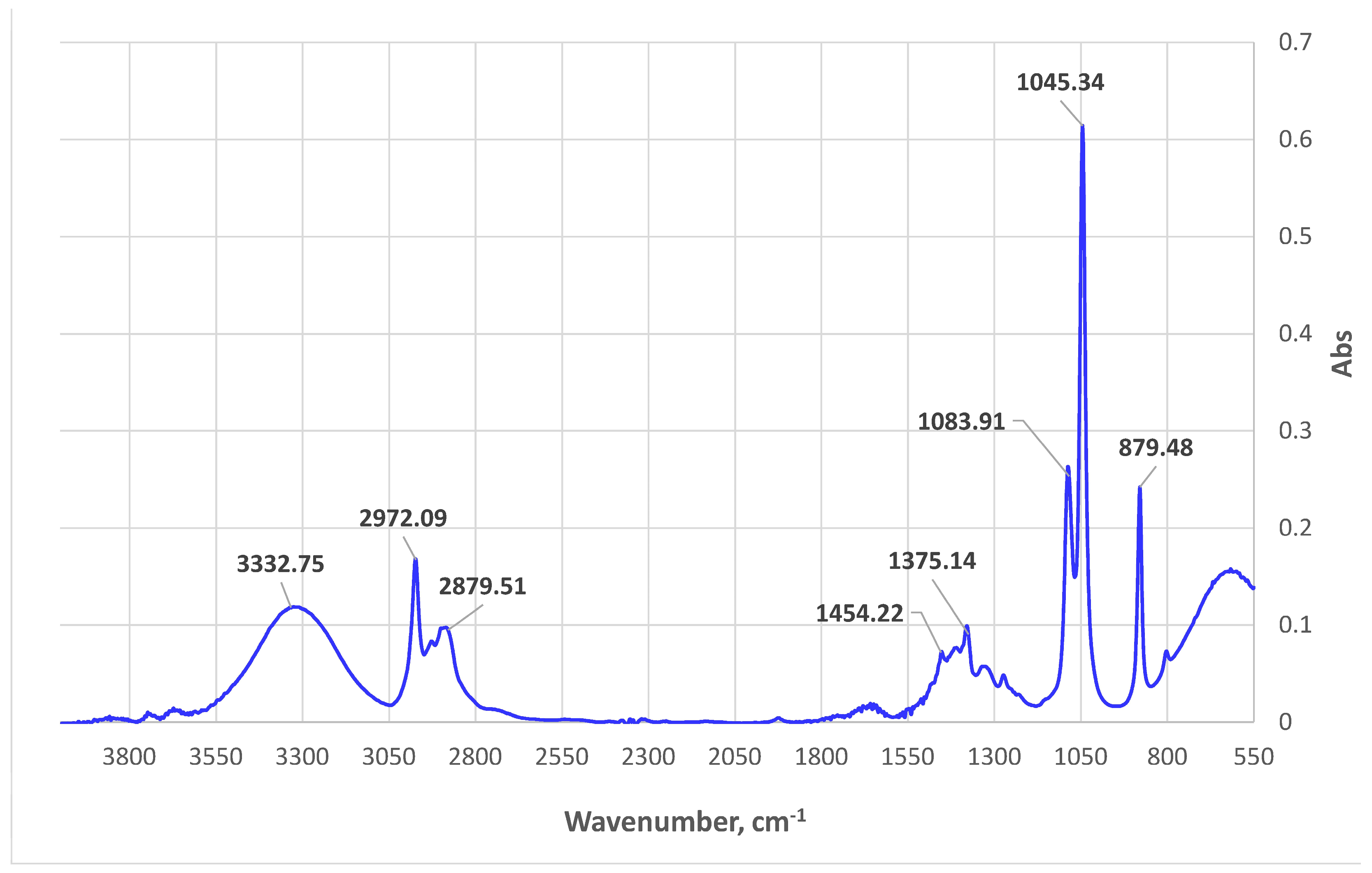

3.2. UV/Vis Spectrophotometric and ATR-FTIR Analyses of Alkanna tinctoria (L.) Extracts

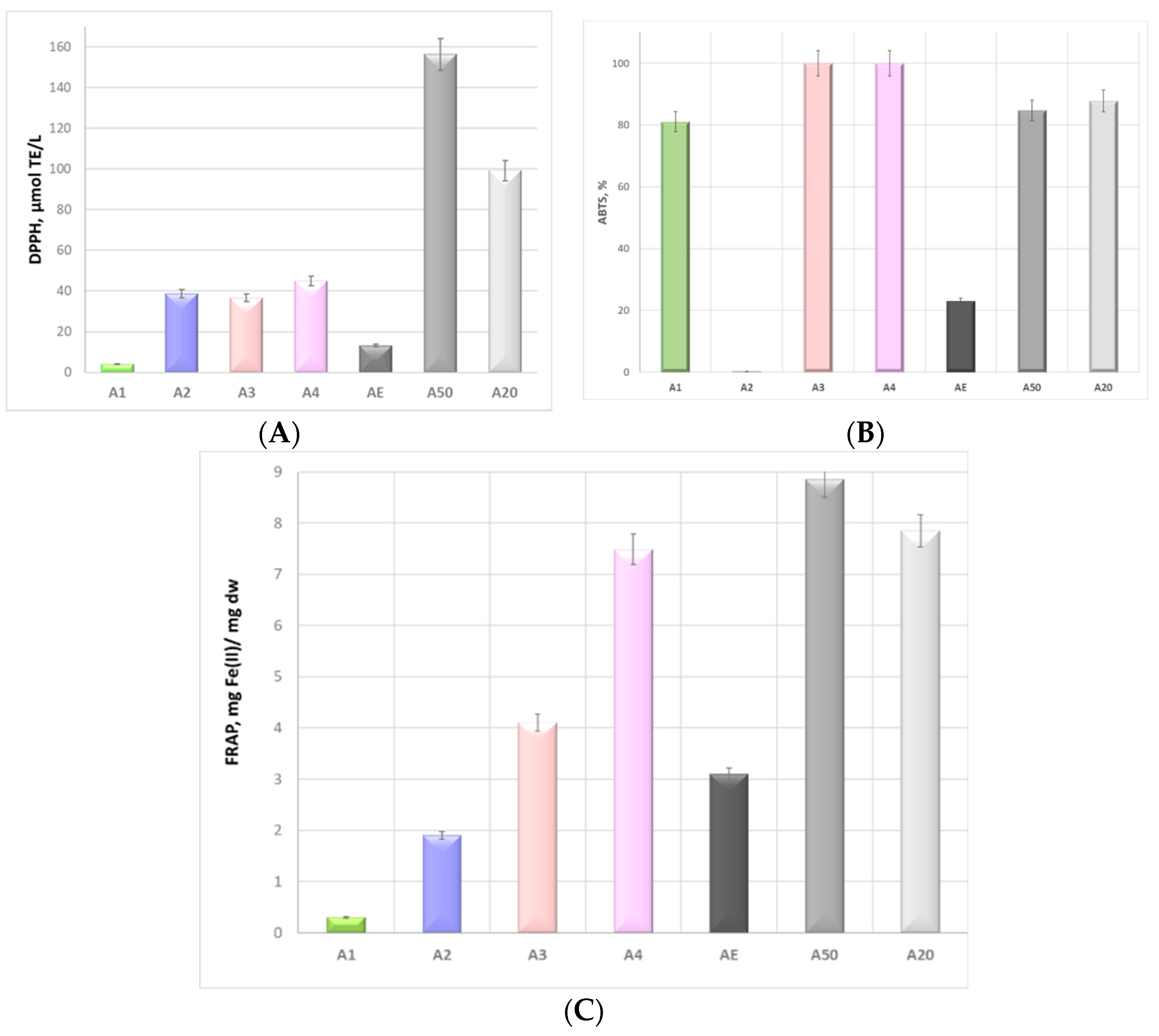

3.3. Radical Scavenging Potential of Alkanet Extracts

3.4. GC-MS Analysis of the Alcohol Extracts

3.5. HPLC-PDA-MS Analysis of Alkanna tinctoria (L.) Extracts

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Nikolova, M.; Aneva, I.; Zhelev, P.; Semerdjieva, I.; Zheljazkov, V.D.; Vladimirov, V.; Stoyanov, S.; Berkov, S.; Yankova-Tsvetkova, E. Metabolic Profiles, Genetic Diversity, and Genome Size of Bulgarian Population of Alkanna tinctoria. Plants 2023, 12, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evstatieva, L. Alkanna tinctoria L. In Red Data Book of Republic of Bulgaria, Plants and Fungi, 2nd ed.; Golemansky, V., Peev, D., Chipev, N., Beron, P., Biserkov, V., Eds.; BAS & MOEW: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2015; Volume 1, p. 380. ISBN 978-954-9746-21-1. [Google Scholar]

- Biodiversity Act in Bulgaria Ministry of Environment and Water in Bulgaria. Available online: https://www.moew.government.bg/en/nature/legislations/national-legislation/laws/ (accessed on 2 February 2025).

- Jaradat, N.A.; Zaid, A.N.; Hussen, F.M.; Issa, L.; Altamimi, M.; Fuqaha, B.; Nawahda, A.; Assadi, M. Phytoconstituents, antioxidant, sun protection and skin anti-wrinkle effects using four solvents fractions of the root bark of the traditional plant Alkanna tinctoria (L.). Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2018, 21, 88–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papageorgiou, V.P.; Assimopoulou, A.N.; Couladouros, E.A.; Hepworth, D.; Nicolaou, K.C. The chemistry and biology of alkannin, shikonin, and related naphthazarin natural products. Angew. Chem. Int. 1999, 38, 270–300. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Gelil, O.E.A.; Atwa, N.A.; Moustafa, A.R.A.; Mansour, S.R. Alkanna Species: A Promising Herbal Medicine and its Uses. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 2, 309–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tung, N.H.; Du, G.J.; Yuan, C.-S.; Shoyama, Y.; Wang, C.Z. Isolation and chemopreventive evaluation of novel naphthoquinone compounds from Alkanna tinctoria. Anti-Cancer Drugs 2013, 24, 1058–1068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganos, C.; Zengin, G.; Chinou, I.; Aligiannis, N.; Graikou, K. Phytochemical Profiling and Biological Assessment of the Aerial Parts from Three Mediterranean Alkanna Species (A. orientalis, A. tinctoria, A. kotschyana) in the Boraginaceae Family. Plants 2024, 13, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Assimopoulou, A.N.; Boskou, D.; Papageorgiou, V.P. Antioxidant activity of alkannin, shikonin and Alkanna tinctoria root extracts in oil substrates. Food Chem. 2004, 87, 433–438. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takci, H.A.M.; Turkmen, F.U.; Anlas, F.C.; Alkan, F.U.; Bakirhan, P.; Demir, C.; Sekeroglu, N. Antimicrobial activity and cytotoxicity of Alkanna tinctoria (L.) Tausch root extracts. Karadeniz Fen Bilim. Derg. 2019, 9, 176–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilavtepe, M.; Erkucuk, A.; Akgun, I.H.; Yesil-Celiktas, O. Supercritical CO2 extraction of Alkanna species and investigating functional characteristics of alkannin-enriched yoghurt during storage. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2012, 234, 807–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, S.; Brudzynska, P.; Khan, M.R.; Sytar, O.; Makhzoum, A.; Sionkowska, A. Natural Plant-Derived Compounds in Food and Cosmetics: A Paradigm of Shikonin and Its Derivatives. Materials 2023, 16, 4377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roeder, E.; Wiedenfeld, H.; Schraut, R. Pyrrolizidine alkaloids from Alkanna tinctoria. Phytochemistry 1984, 23, 2125–2126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulder, P.P.J.; Sánchez, P.L.; These, A.; Preiss-Weigert, A.; Castellari, M. Occurrence of Pyrrolizidine Alkaloids in food. EFSA Support. Publ. 2015, 12, 859E. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, A.; Biswas, S.; Satyaprakash, K.; Bhattacharya, D.; Nanda, P.K.; Patra, G.; Moirangthem, S.; Nath, S.; Dhar, P.; Verma, A.K.; et al. Ratanjot (Alkanna tinctoria L.) Root Extract, Rich in Antioxidants, Exhibits Strong Antimicrobial Activity against Foodborne Pathogens and Is a Potential Food Preservative. Foods 2024, 13, 2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzanova, M.T.; Yaneva, Z.; Ivanova, D.; Toneva, M.; Grozeva, N.; Memdueva, N. Green Solvents for Extraction of Natural Food Colorants from Plants: Selectivity and Stability Issues. Foods 2024, 13, 605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negi, T.; Kumar, A.; Sharma, S.K.; Rawat, N.; Saini, D.; Sirohi, R.; Prakash, O.; Dubey, A.; Dutta, A.; Shahi, N.C. Deep eutectic solvents: Preparation, properties, and food applications. Heliyon 2024, 10, e28784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; Witkamp, G.J.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Tailoring properties of natural deep eutectic solvents with water to facilitate their applications. Food Chem. 2015, 187, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zannou, O.; Koca, I. Optimization and stabilization of the antioxidant properties from Alkanet (Alkanna tinctoria) with natural deep eutectic solvents. Arab. J. Chem. 2020, 13, 6437–6450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aroso, I.M.; Paiva, A.; Reis, R.L.; Duarte, A.R.C. Natural deep eutectic solvents from choline chloride and betaine—Physicochemical properties. J. Mol. Liq. 2017, 241, 654–661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, Y.; van Spronsen, J.; Witkamp, G.J.; Verpoorte, R.; Choi, Y.H. Natural deep eutectic solvents as new potential media for green technology. Anal. Chim. Acta 2013, 766, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bossard, E.; Tsafantakis, N.; Aligiannis, N.; Fokialakis, N. Natural deep eutectic solvents: An eco-friendly alternative for the extraction of naphthoquinones from Alkanna tinctoria roots. Planta Med. 2019, 85, 1494–1495. [Google Scholar]

- Bossard, E.; Tsafantakis, N.; Aligiannis, N.; Fokialakis, N. A Development Strategy of Tailor-made Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Enhanced Extraction of Hydroxynaphthoquinones from Alkanna tinctoria Roots. Planta Med. 2022, 88, 826–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tzanova, M.; Atanasov, V.; Yaneva, Z.; Ivanova, D.; Dinev, T. Selectivity of Current Extraction Techniques for Flavonoids from Plant Materials. Processes 2020, 8, 1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaneva, Z.; Simeonov, E.; Ivanova, D. In vitro Ultraviolet-B radiation mediated antioxidant response of Bulgarian Goldenrod (Solidago virgaurea L.) extract. Bulg. Chem. Commun. 2020, 52, 33–40. [Google Scholar]

- Re, R.; Pellegrini, N.; Proteggente, A.; Pannala, A.; Yang, M.; Rice-Evans, C. Antioxidant activity applying an improved ABTS radical cation decolorization assay. Free Rad. Biol. Med. 1999, 26, 1231–1237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Karamalakova, Y.; Sharma, J.; Nikolova, G.; Stanev, S.; Arora, R.; Gadjeva, V.; Zheleva, A. Studies on antioxidant properties before and after UV-And Γ-Irradiation of Bulgarian lavender essential oil isolated from Lavandula Angostifolia mill. Biotechnol. Biotechnol. Equipm. 2013, 27, 3861–3865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaneva, Z.; Ivanova, D.; Toneva, M. Green Synthesis, Characterization, Encapsulation, and Measurement of the Release Potential of Novel Alkali Lignin Micro-/Submicron Particles. J. Vis. Exp. 2024, 205, e66216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinev, T.; Tzanova, M.; Velichkova, K.; Dermendzhieva, D.; Beev, G. Antifungal and Antioxidant Potential of Methanolic Extracts from Acorus calamus L., Chlorella vulgaris Beijerinck, Lemna minuta Kunth and Scenedesmus dimorphus (Turpin) Kützing. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 4745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rebaya, A.; Belghith, S.I.; Baghdikian, B.; Leddet, V.M.; Mabrouki, F.; Olivier, E.; Cherif, J.; Ayadi, M.T. Total Phenolic, Total Flavonoid, Tannin Content, and Antioxidant Capacity of Halimium halimifolium (Cistaceae). J. App. Pharm. Sci. 2015, 5, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, J.; Durst, R.W.; Wrolstad, R.E. Determination of total monomeric anthocyanin pigment content of fruit juices, beverages, natural colorants, and wines by the pH differential method: Collaborative study. J. AOAC Int. 2005, 88, 1269–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- John, B.; Sulaiman, C.T.; Satheesh, G.; Reddy, V.R.K. Spectrophotometric estimation of total alkaloids in selected Justicia species. Int. J. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2014, 6, 647–648. [Google Scholar]

- Rana, S.; Chauhan, P. Spices That Heal: Review on Untapped Potential of Lesser-Known Spices as Immunity Booster during COVID-19 Pandemic. Ann. Phytomed. Int. J. 2022, 11, 7–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeel, S.; Kiran, S.; Alam, M.; Farooq, T.; Amin, N.; Gulzar, T. Alkanna tinctoria-Based Sustainable Alkanin Natural Colorant for Eco-Dyeing of Wool. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 27073–27080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assimopoulou, A.N.; Papageorgiou, V.P. Radical Scavenging Activity of Alkanna tinctoria Root Extracts and their Main Constituents, Hydroxynaphthoquinones. Phytother Res. 2005, 19, 141–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alwahibi, M.S.; Perveen, K. Chemical analysis by GC-MS and in vitro antibacterial activity of Alkanna tinctoria extracts against skin infection causing bacteria. Biomed. Res. 2017, 28, 7946–7949. [Google Scholar]

- Assimopoulou, A.N.; Karapanagiotis, I.; Vasiliou, A.; Kokkini, S.; Papageorgiou, V.P. Analysis of alkannin derivatives from Alkanna species by high-performance liquid chromatography/photodiode array/mass spectrometry. Biomed. Chromatogr. 2006, 20, 1359–1374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siamandoura, P.; Tzia, C. Comparative Study of Novel Methods for Olive Leaf Phenolic Compound Extraction Using NADES as Solvents. Molecules 2023, 28, 353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huang, Y.; Feng, F.; Jiang, J.; Qiao, Y.; Wu, T.; Voglmeir, J.; Chen, Z.G. Green and efficient extraction of rutin from tartary buckwheat hull by using natural deep eutectic solvents. Food Chem. 2017, 221, 1400–1405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohilla, S.; Mahanta, C.L. Optimization of extraction conditions for ultrasound-assisted extraction of phenolic compounds from tamarillo fruit (Solanum betaceum) using response surface methodology. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 1763–1773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, K.; Srivastav, S.; Sharanagat, V.S. Ultrasound assisted extraction (UAE) of bioactive compounds from fruit and vegetable processing by-products: A review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 70, 105325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vannuchi, N.; Ramos, S.P.; Mazzo, T.M.; Longo, E.; Bonsanto, F.P.; Braga, A.R.C.; de Rosso, V.V. Natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES)-Extracted Anthocyanins: Bioaccessibility in electrospun PEO microfibers. Food Res. Internat. 2024, 177, 113898. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, J.; Xie, L.; Peng, Y.; Li, M.; Li, J.; Ni, Y.; Wen, X. Deep Eutectic Solvents as New Extraction Media for Flavonoids in Mung Bean. Foods 2024, 13, 777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benvenutti, L.; Zielinski, A.A.F.; Ferreira, S.R.S. Pressurized aqueous solutions of deep eutectic solvent (DES): A green emergent extraction of anthocyanins from a Brazilian berry processing by-product. Food Chem. X 2022, 13, 100236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Friesen, J.B.; McAlpine, J.B.; Lankin, D.C.; Chen, S.-N.; Pauli, G.F. Natural deep eutectic solvents: Properties, applications, and perspectives. J. Nat. Prod. 2018, 81, 679–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shishov, A.; Dubrovsky, I.; Kirichenko, S.; Bulatov, A. Behavior of quaternary ammonium salts and terpenoids-based deep eutectic solvents in aqueous phase. J. Mol. Liq. 2021, 40, 117987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikmawanti, N.P.E.; Saputri, F.C.; Yanuar, A.; Jantan, I.; Ningrum, R.A.; Juanssilfero, A.B.; Munim, A. Choline chloride-urea-based natural deep eutectic solvent for highly efficient extraction of polyphenolic antioxidants from Pluchea indica (L.) Less leaves. Arab. J. Chem. 2024, 17, 105537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Urios, C.; Puchades-Colera, P.; Frigola, A.; Esteve, M.J.; Blesa, J.; Lopez-Malo, D. Natural deep eutectic solvents: A paradigm of stability and permeability in the design of new ingredients. J. Mol. Liq. 2024, 412, 125864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saha, S.K.; Dey, S.; Chakraborty, R. Effect of choline chloride-oxalic acid based deep eutectic solvent on the ultrasonic assisted extraction of polyphenols from Aegle marmelos. J. Mol. Liq. 2019, 287, 110956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akinboye, A.J.; Kim, K.; Choi, S.; Yang, I.; Lee, J.G. Alkaloids in food: A review of toxicity, analytical methods, occurrence and risk assessments. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2023, 32, 1133–1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sisa, M.; Bonnet, S.L.; Ferreira, D.; Van der Westhuizen, J.H. Photochemistry of Flavonoids. Molecules 2010, 15, 5196–5245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldhar, R.; Prasad, D.; Saxena, A.; Kaur, A. Corrosion resistance of mild steel in 0.5 M H2SO4 solution by plant extract of Alkana tinctoria: Experimental and theoretical studies. Eur. Phys. J. Plus. 2018, 133, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brangule, A.; Šukele, R.; Bandere, D. Herbal medicine characterization perspectives using advanced FTIR sample techniques-Diffuse Reflectance (DRIFT) and Photoacoustic Spectroscopy (PAS). Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pharmawati, M.; Wrasiati, L.P. Phytochemical screening and FTIR spectroscopy on crude extract from Enhalus acoroides leaves. Malays. J. Anal. Sci. 2020, 24, 70–77. [Google Scholar]

- Lakka, A.; Grigorakis, S.; Karageorgou, I.; Batra, G.; Kaltsa, O.; Bozinou, E.; Lalas, S.; Makris, D.P. Saffron processing wastes as a bioresource of high-value added compounds: Development of a green extraction process for polyphenol recovery using a natural deep eutectic solvent. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, P.; Wang, X.; Liu, P.; Huang, J.; Wang, C.; Pan, M.; Kuang, Z. Enhanced phenolic compounds extraction from Morus alba L. leaves by deep eutectic solvents combined with ultrasonic assisted extraction. Ind. Crops Prod. 2018, 120, 147–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakirtzi, C.; Triantafyllidou, K.; Makris, D.P. Novel lactic acid based natural deep eutectic solvents: Efficiency in the ultrasound assisted extraction of antioxidant polyphenols from common native Greek medicinal plants. J. Appl. Res. Med. Aroma 2016, 3, 120–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švestková, P.; Balík, J.; Soural, I. Synergistic effect of selected carboxylic acids and phenolic compounds detected by the FRAP method. Food Chem. X 2024, 23, 101573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gawron-Skarbek, A.; Guligowska, A.; Prymont-Przymińska, A.; Nowak, D.; Kostka, T. The Anti-Inflammatory and Antioxidant Impact of Dietary Fatty Acids in Cardiovascular Protection in Older Adults May Be Related to Vitamin C Intake. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruk, J.; Aboul-Enein, B.H.; Duchnik, E.; Marchlewicz, M. Antioxidative properties of phenolic compounds and their effect on oxidative stress induced by severe physical exercise. J. Physiol. Sci. 2022, 72, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peinado, J.; López de Lerma, N.; Peinado, R.A. Synergistic antioxidant interaction between sugars and phenolics from a sweet wine. Eur. Food Res. Technol. 2010, 231, 363–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopjar, M.; Lončarić, A.; Mikulinjak, M.; Šrajbek, Ž.; Šrajbek, M.; Pichler, A. Evaluation of Antioxidant Interactions of Combined Model Systems of Phenolics in the Presence of Sugars. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2016, 11, 1445–1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, H.H.; Kuo, C.H. Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry-based analytical strategies for fatty acid analysis in biological samples. J. Food Drug Anal. 2020, 28, 60–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Lou, Z.; Zhang, H.; Tan, G.; Liu, Z.; Li, W.; Zhu, Z.; Chai, Y. Identification of multiple components in Guanxinning injection using hydrophilic interaction liquid chromatography/time-of-flight mass spectrometry and reversed-phase liquid chromatography/time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Rapid Commun. Mass Spectrom. 2011, 25, 1661–1674. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Extract ID | Solvent | |||||||

| Classical solvents | pH Adjusted by conc. CH3COOH | |||||||

| AE | Ethanol | |||||||

| A50 | 50% Ethanol at | pH = 2 | ||||||

| A20 | 20% Ethanol | pH = 3 | ||||||

| Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES) | ||||||||

| NADES ID | HBA | HBD | H2O | Molar ratio | Temperature, T °C | Time, t, min | pH | |

| A1 | NADES 1 | choline chloride | urea | 0% | 1:2 | 80 °C | 60 | pH = 5.55 |

| A2 | NADES 2 | choline chloride | citric acid | 30% | 1:2 | 80 °C | 60 | pH = −0.84 |

| A3 | NADES 3 | choline chloride | lactic acid | 0% | 1:2 | 60 °C | 20 | pH = 0.66 |

| A4 | NADES 4 | Na-acetate | formic acid | 0% | 1:2 | 75 °C | 30 | pH = 3.03 |

| Sample ID | TPC | TFC | TCT | TAntC | TAlkC |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mgGAE/L | mgCE/L | mgCE/L | mgCGE/L | µgAE/L | |

| AE | 286 ± 19 | 203 ± 13 | 43 ± 3 | 18 ± 1 | 24 ± 1 |

| A50 | 1318 ± 63 | 708 ± 32 | 20 ± 1 | 3.0 ± 0.2 | 256 ± 15 |

| A20 | 1009 ± 41 | 402 ± 27 | 6.3 ± 0.4 | 4.1 ± 0.3 | 241 ± 13 |

| A1 | 44 ± 3 | 279 ± 17 | 78 ± 6 | 25 ± 1 | 5.1 ± 0.4 |

| A2 | 108 ± 7 | 31 ± 2 | 27 ± 2 | 4.2 ± 0.3 | 189 ± 11 |

| A3 | 46 ± 4 | 38 ± 3 | 24 ± 1 | 12.2 ± 0.7 | 372 ± 22 |

| A4 | 355 ± 21 | 104 ± 6 | 163 ± 10 | 26 ± 1 | 7.0 ± 0.5 |

| DPPH | ABTS | FRAP | TPC | TFC | TCT | TAntC | TAlkC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH | 1 | 0.9006 * | 0.5198 | 0.9937 * | 0.9724 * | −0.7099 | −0.9411 | 0.9394 * |

| ABTS | 1 | 0.8394 | 0.9437 * | 0.7743 | −0.9454 | −0.9945 | 0.9950 * | |

| FRAP | 1 | 0.6123 | 0.3061 | −0.9707 | −0.7781 | 0.7812 | ||

| TPC | 1 | 0.9400 * | −0.7844 | −0.9731 | 0.9719 * | |||

| TFC | 1 | −0.5259 | −0.8362 | 0.8334 | ||||

| TCT | 1 | 0.9062 * | −0.9083 | |||||

| TAntC | 1 | −0.9999 | ||||||

| TAlkC | 1 |

| DPPH | ABTS | FRAP | TPC | TFC | TCT | TAntC | TAlkC | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| DPPH | 1 | −0.0938 | −0.1466 | 0.5940 | −0.8894 | 0.1376 | −0.3878 | 0.3593 |

| ABTS | 1 | 0.9866 * | 0.2263 | 0.3058 | 0.4851 | 0.7302 | −0.0782 | |

| FRAP | 1 | 0.0739 | 0.2873 | 0.3371 | 0.6452 | 0.0470 | ||

| TPC | 1 | −0.1647 | 0.8671 * | −0.9731 | −0.5010 | |||

| TFC | 1 | 0.3304 | 0.7412 | −0.7014 | ||||

| TCT | 1 | 0.8109 | −0.7698 | |||||

| TAntC | 1 | −0.7327 | ||||||

| TAlkC | 1 |

| RI | Compound | AE | A50 | A20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alcohols | ||||

| 1287 | Glycerol | 0.40 ± 0.18 | 0.76 ± 0.22 | 0.86 ± 0.27 |

| 1873 | 6-O-Methyl-myo-inositol | 1678.44 ± 21.90 | 1782.09 ± 25.18 | 2033.15 ± 32.24 |

| 1921 | Mannitol | 0.89 ± 0.29 | 1.20 ± 0.50 | 1.45 ± 0.70 |

| 1962 | 4-O-Methyl-myo-inositol | 2002.26 ± 30.01 | 2567.16 ± 40.14 | 3132.26 ± 46.90 |

| 2429 | myo-Inositol-1-phosphate | 13.80 ± 3.22 | 16.23 ± 3.90 | 15.31 ± 4.76 |

| 2433 | myo-Inositol-2-phosphate | 28.83 ± 6.04 | 17.39 ± 4.08 | 14.34 ± 3.31 |

| 2779 | 1-Monooctadecanoylglycerol | 33.70 ± 7.15 | 9.06 ± 3.15 | 12.28 ± 5.05 |

| Organic acids | ||||

| 1341 | Glyceric acid | nd | 5.89 ± 1.45 | 4.13 ± 1.93 |

| 1490 | Malic acid | 4.77 ± 1.76 | 3.84 ± 0.93 | 9.52 ± 2.50 |

| 1989 | Gluconic acid | 0.49 ± 0.19 | nd | 0.79 ± 0.38 |

| Phenolic acids | ||||

| 1628 | 4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | 9.02 ± 2.37 | 16.15 ± 4.09 | 14.10 ± 3.78 |

| 1779 | 4-Hydroxy-3-methoxybenzoic acid | 0.36 ± 0.14 | 0.97 ± 0.40 | 0.77 ± 0.24 |

| 1843 | 4-Methoxycinnamic acid | 0.30 ± 0.10 | 0.42 ± 0.18 | 0.90 ± 0.32 |

| 1938 | trans-p-Coumaric acid | nd | 1.06 ± 0.71 | 0.69 ± 0.19 |

| 2100 | trans-Ferulic acid | 0.73 ± 0.25 | 0.60 ± 0.19 | 0.43 ± 0.15 |

| 2144 | trans-Caffeic acid | 24.19 ± 4.28 | 28.17 ± 4.07 | 38.92 ± 5.17 |

| Mono- and disaccharides | ||||

| 1673 | Arabinose | 22.01 ± 3.12 | 51.28 ± 5.04 | 30.45 ± 4.54 |

| 1866 | Fructose isomer 1 | 203.39 ± 21.24 | 284.14 ± 30.16 | 366.25 ± 33.12 |

| 1888 | Fructose isomer 2 | 51.56 ± 6.71 | 33.18 ± 2.73 | 70.28 ± 7.17 |

| 1892 | Manose | 8.78 ± 1.72 | 4.11 ± 1.25 | 11.18 ± 2.52 |

| 1899 | Glucose isomer 1 | 240.01 ± 15.15 | 200.07 ± 15.19 | 187.90 ± 12.41 |

| 1913 | Glucose isomer 2 | 70.14 ± 6.93 | 81.28 ± 5.90 | 93.33 ± 7.79 |

| 1977 | Glucopyranose | 27.55 ± 5.86 | 60.31 ± 6.00 | 45.22 ± 3.96 |

| 2647 | Sucrose isomer 1 | 1279.37 ± 17.04 | 935.41 ± 30.45 | 789.51 ± 20.72 |

| 2660 | Sucrose isomer 2 | 13.59 ± 2.60 | 34.56 ± 2.93 | 20.50 ± 2.11 |

| Fatty acids | ||||

| 2040 | Palmitic Acid | 111.06 ± 10.05 | 19.62 ± 2.56 | 63.02 ± 8.01 |

| 2238 | Stearic acid | 15.41 ± 1.88 | nd | nd |

| № | Compound | Rt (min) a | UV–Vis (nm) | Molecular Formula | Ion Type | m/z | Extract ID | Method | Method of Identif. b | Ref. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AE | A50 | A20 | A1 | A2 | A3 | A4 | ||||||||||

| 1 | β,β-Dimethylacrylalkannin | 14.59 | 517, 274 | C21H22O6 | [M − H]− | 369 | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | M1 | MS | [37] |

| 2 | Isovalerylalkannin + α-Methyl-n-butylalkannin | 15.10 | 517, 274 | C21H24O6/ C22H26O5 | [M − H]− | 371 | + | + | - | - | - | - | + | M1 | MS | [37] |

| 3 | Syringic acid | 2.07 | 276 | C9H10O5 | [M − H]− | 197 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | M2 | MS, RS | - |

| 4 | Unknown | 2.76 | 259 | 358 | + | + | + | + | - | - | - | M2 | MS | - | ||

| 5 | Caffeic acid | 6.10 | 288, 235 | C9H8O4 | [M − H]− | 179 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | M2 | MS, RS | [8] |

| 6 | Unknown | 10.45 | 278 | 645 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | M2 | MS | - | ||

| 7 | Unknown | 12.44 | 266 | 571 | - | + | + | - | - | - | - | M2 | MS | - | ||

| 8 | Lithospermic acid | 12.80 | 330, 254 | C27H22O12 | [M − H]− | 537 | + | + | + | - | + | - | + | M2 | MS | [8] |

| 9 | Rutin | 13.28 | 355, 256 | C27H30O16 | [M − H]− | 609 | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | M2 | MS, RS | - |

| 10 | Rabdosiin | 15.27 | 347, 283 | C36H30O16 | [M − H]− | 717 | + | + | + | + | + | - | + | M2 | MS | [8] |

| 11 | Rosmarinic acid | 16.93 | 330, 248 | C18H16O8 | [M − H]− | 359 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | M2 | MS, RS | [8] |

| 12 | Unknown | 17.15 | 310, 255 | 983 | + | + | + | - | - | - | + | M2 | MS | - | ||

| 13 | Salvianolic acid A isomer | 17.80 | 309, 254 | C26H22O10 | [M − H]− | 493 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | M2 | MS | [64] |

| 14 | Lithospermic acid isomer I | 18.10 | 353, 254, 201 | C36H30O16 | [M − H]− | 717 | + | + | + | - | - | - | - | M2 | MS | [8] |

| 15 | Salvianolic acid B | 19.10 | 310, 286, 253 | C36H30O16 | [M − H]− | 717 | + | + | + | + | + | + | + | M2 | MS, RS | [8] |

| 16 | Salvianolic acid isomer I or Lithospermic acid isomer II | 19.39 | 308, 284, 250 | C36H30O16 | [M − H]− | 717 | + | + | + | + | + | - | - | M2 | MS | [64] |

| 17 | Salvianolic acid isomer II or Lithospermic acid isomer III | 20.60 | 312, 283, 258 | C36H30O16 | [M − H]− | 717 | + | + | + | - | + | + | + | M2 | MS | [64] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yaneva, Z.; Grozeva, N.; Todorova, M.; Kamenova-Nacheva, M.; Staleva, P.; Memdueva, N.; Tzanova, M.T. Comparison of the Potential of “Green” Classical and Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents in the Production of Natural Food Colorant Extracts from the Roots of Alkanna tinctoria (L.). Foods 2025, 14, 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14040584

Yaneva Z, Grozeva N, Todorova M, Kamenova-Nacheva M, Staleva P, Memdueva N, Tzanova MT. Comparison of the Potential of “Green” Classical and Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents in the Production of Natural Food Colorant Extracts from the Roots of Alkanna tinctoria (L.). Foods. 2025; 14(4):584. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14040584

Chicago/Turabian StyleYaneva, Zvezdelina, Neli Grozeva, Mima Todorova, Mariana Kamenova-Nacheva, Plamena Staleva, Neli Memdueva, and Milena Tankova Tzanova. 2025. "Comparison of the Potential of “Green” Classical and Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents in the Production of Natural Food Colorant Extracts from the Roots of Alkanna tinctoria (L.)" Foods 14, no. 4: 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14040584

APA StyleYaneva, Z., Grozeva, N., Todorova, M., Kamenova-Nacheva, M., Staleva, P., Memdueva, N., & Tzanova, M. T. (2025). Comparison of the Potential of “Green” Classical and Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents in the Production of Natural Food Colorant Extracts from the Roots of Alkanna tinctoria (L.). Foods, 14(4), 584. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14040584