Exploring the Sensory Odor Profile of Sourdough Starter from Ancient Whole-Wheat Flours in the Development of Cookies with Enhanced Quality

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Sourdough Preparation

2.3. Sourdough Starter Sensory Analysis

2.3.1. Dynamic Odor Perception via Temporal Dominance of Sensations (TDS)

2.3.2. Quantitative Descriptive Analysis (QDA)

2.4. Consumer Study of Sourdough: Overall Liking Study and Check-All-That-Apply (CATA)

2.5. Cookies Preparation

2.6. Cookies Analysis

2.6.1. Cookie Proximate Composition

2.6.2. Colour Determination of Cookies

2.6.3. Textural Properties of Cookies

2.6.4. Sensory Analysis of Cookies

2.7. Data Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Sourdough Starter Sensory Analysis

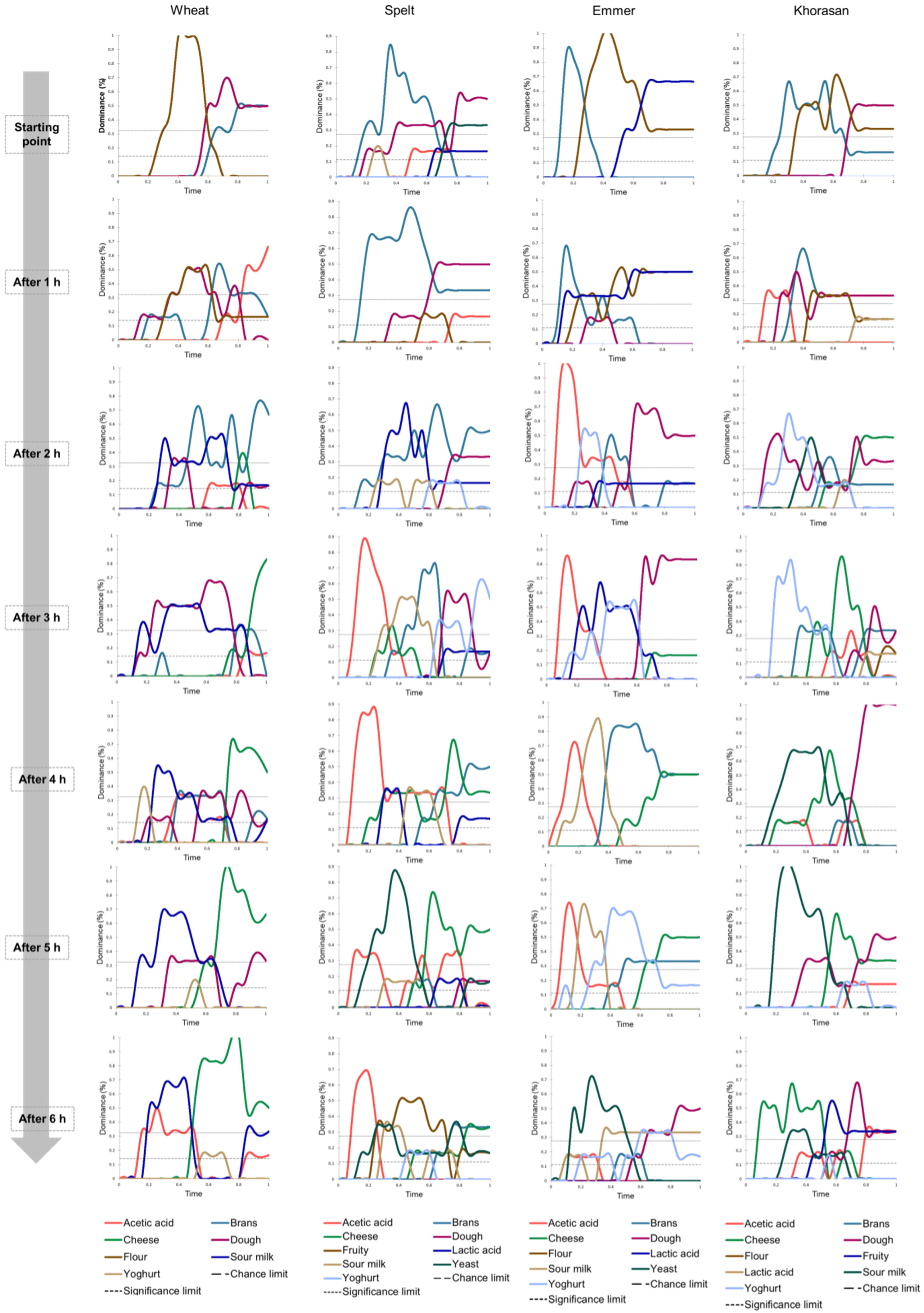

3.1.1. Dynamic Odor Perception via TDS

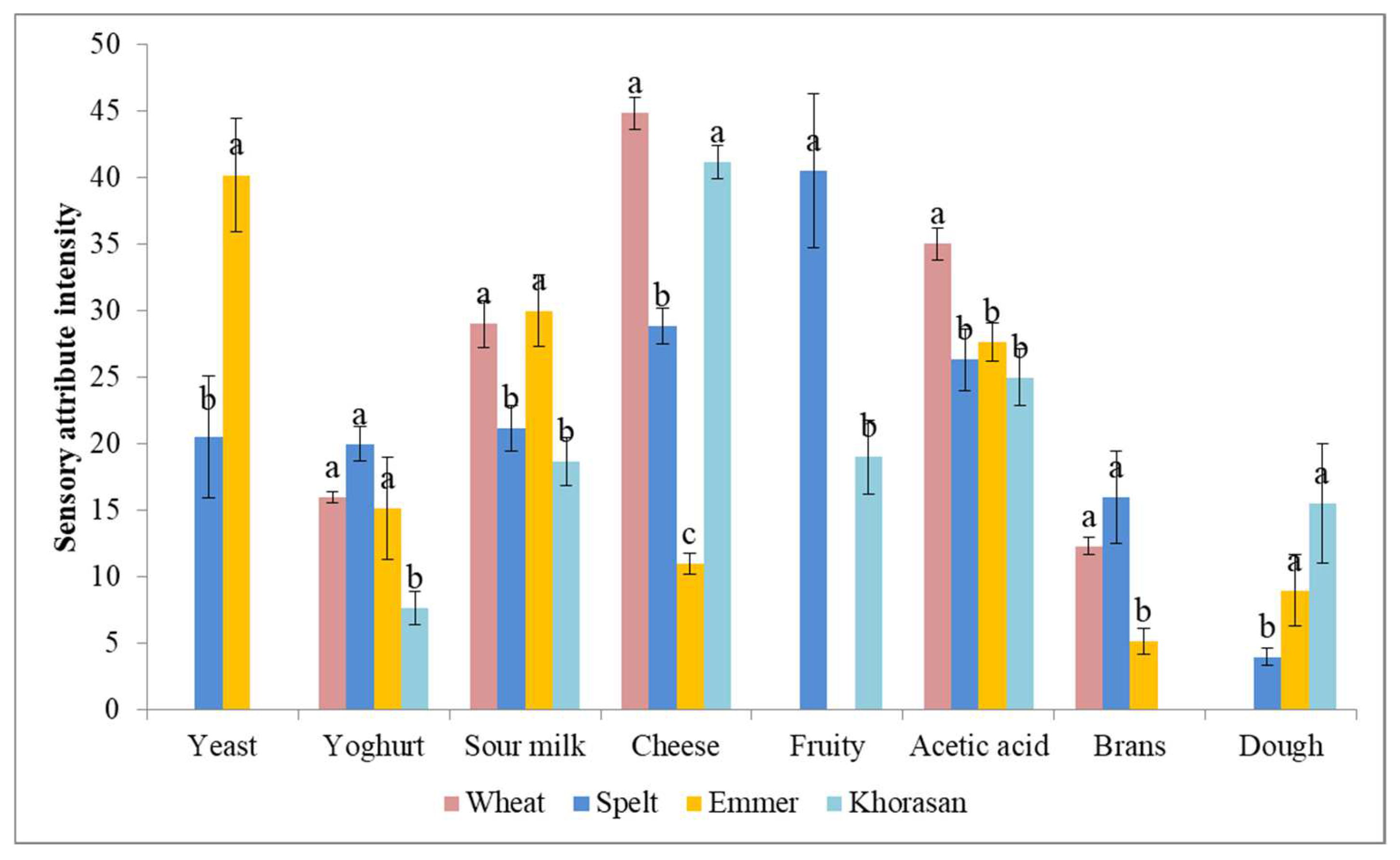

3.1.2. Static Descriptive Analysis of Sourdough Odor via QDA

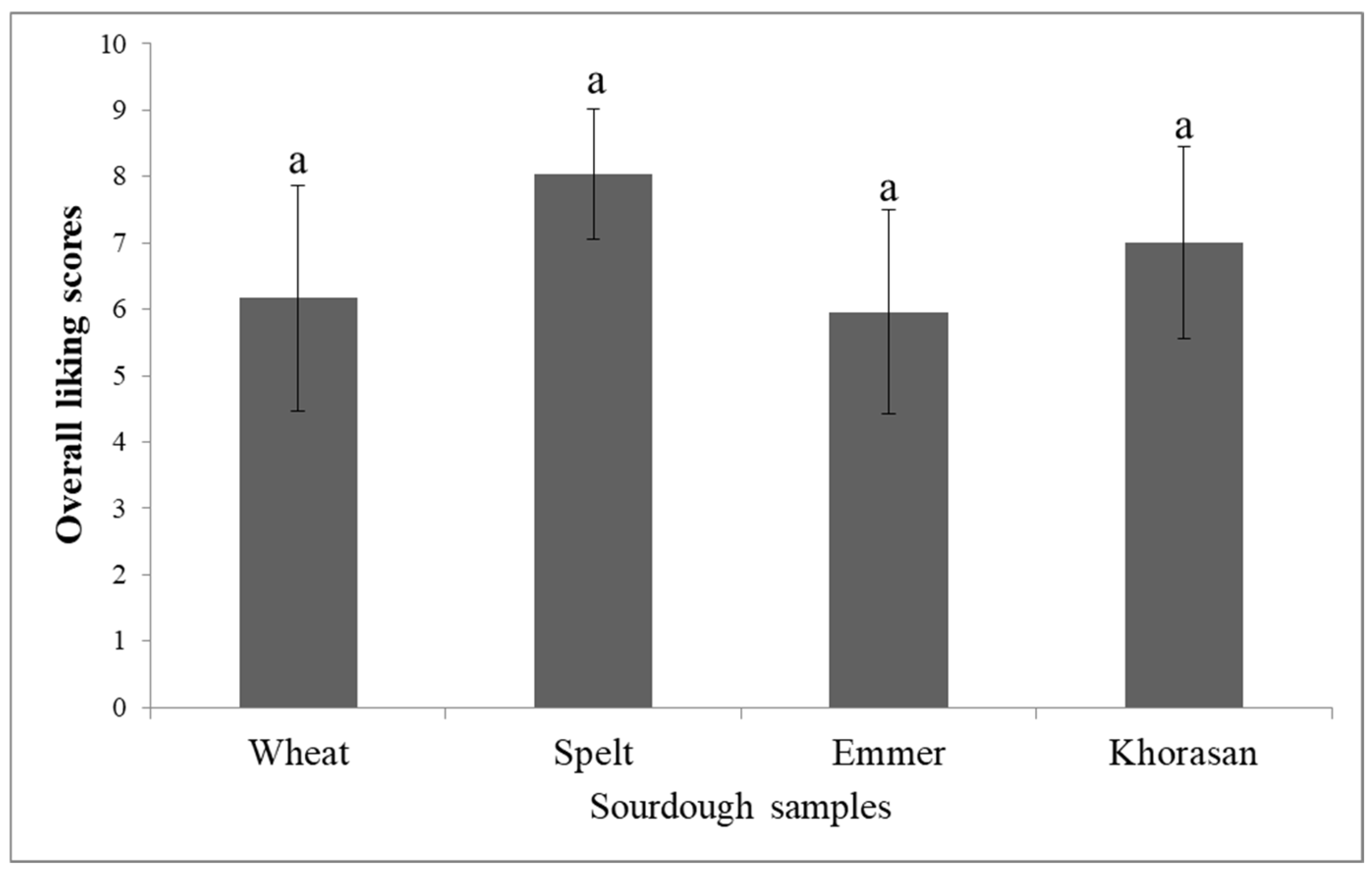

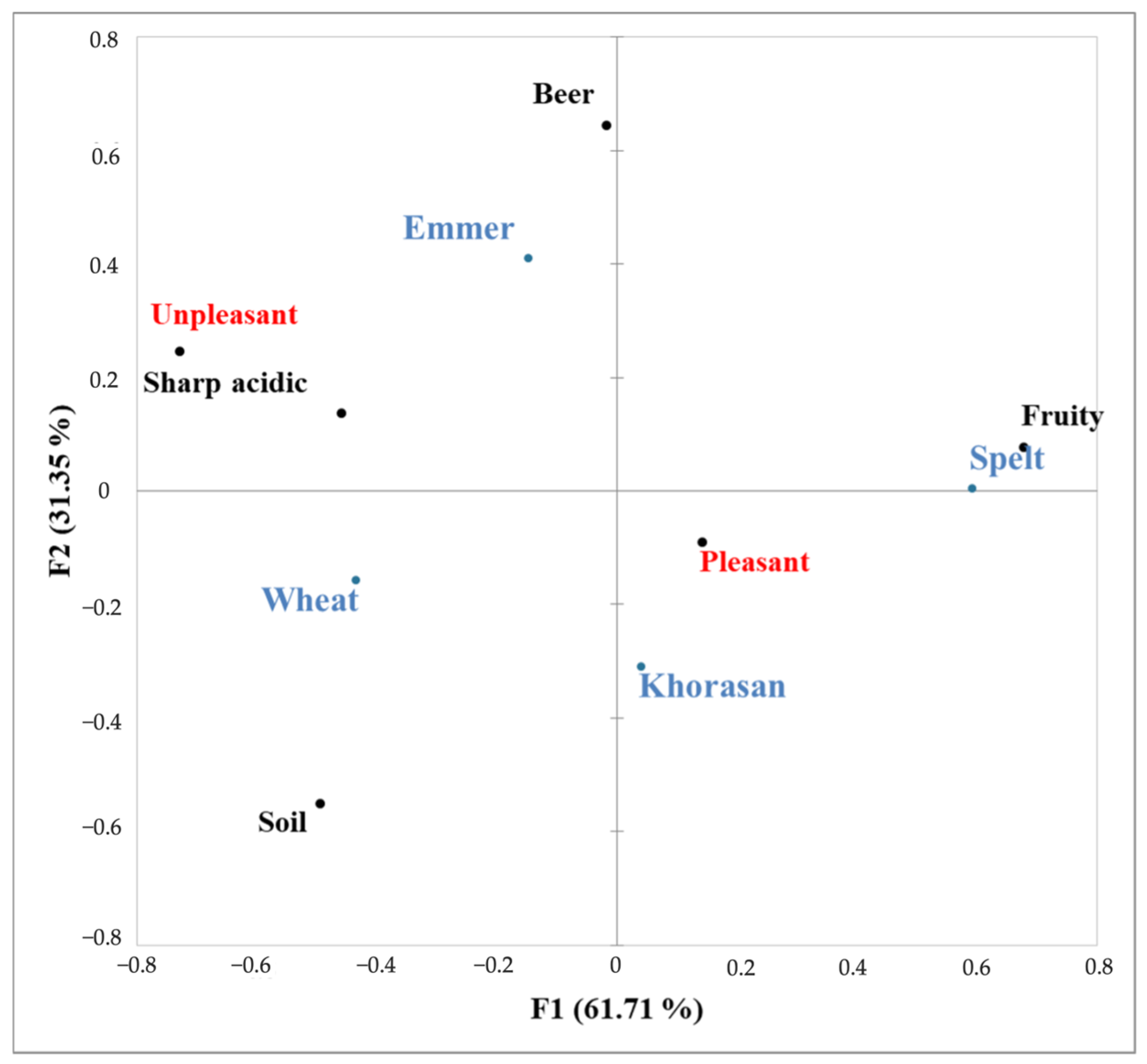

3.2. Overall Liking and CATA Questions

3.3. Cookie Analysis

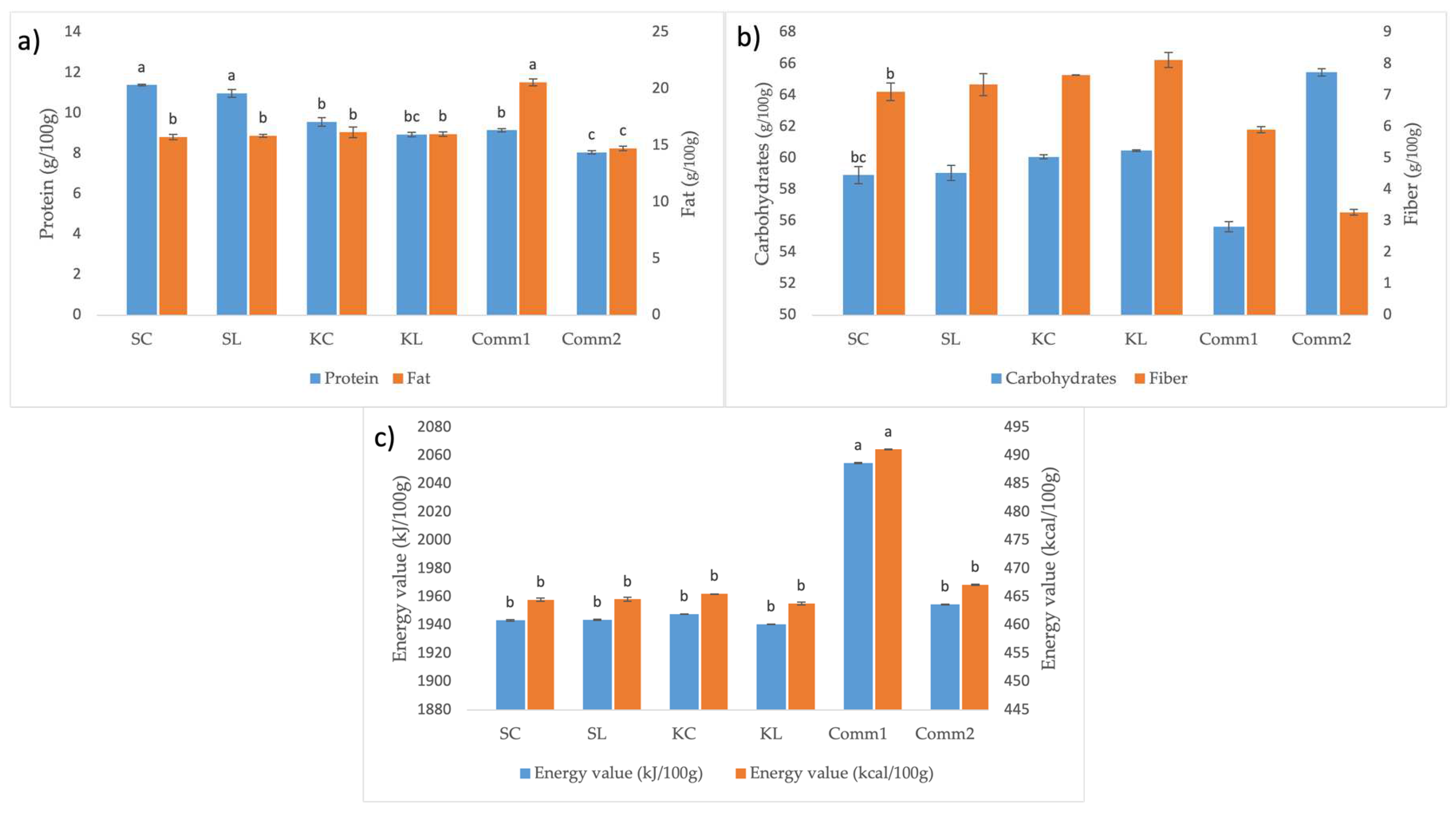

3.3.1. Proximate Composition of Cookies

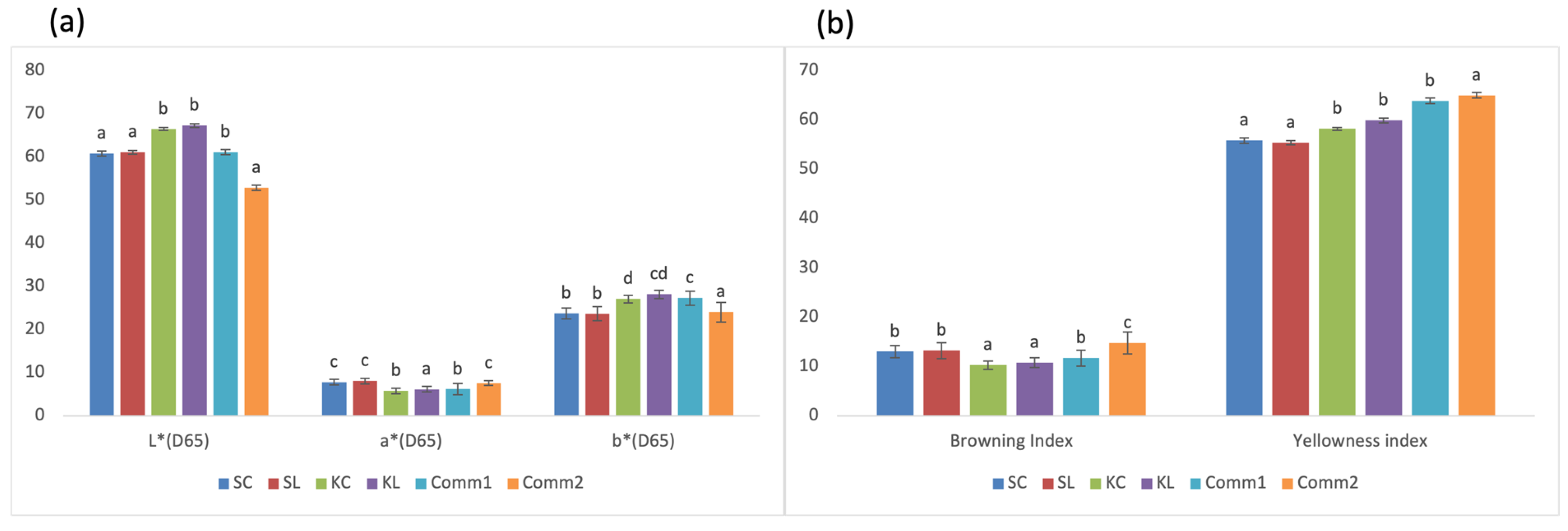

3.3.2. Color Measurement

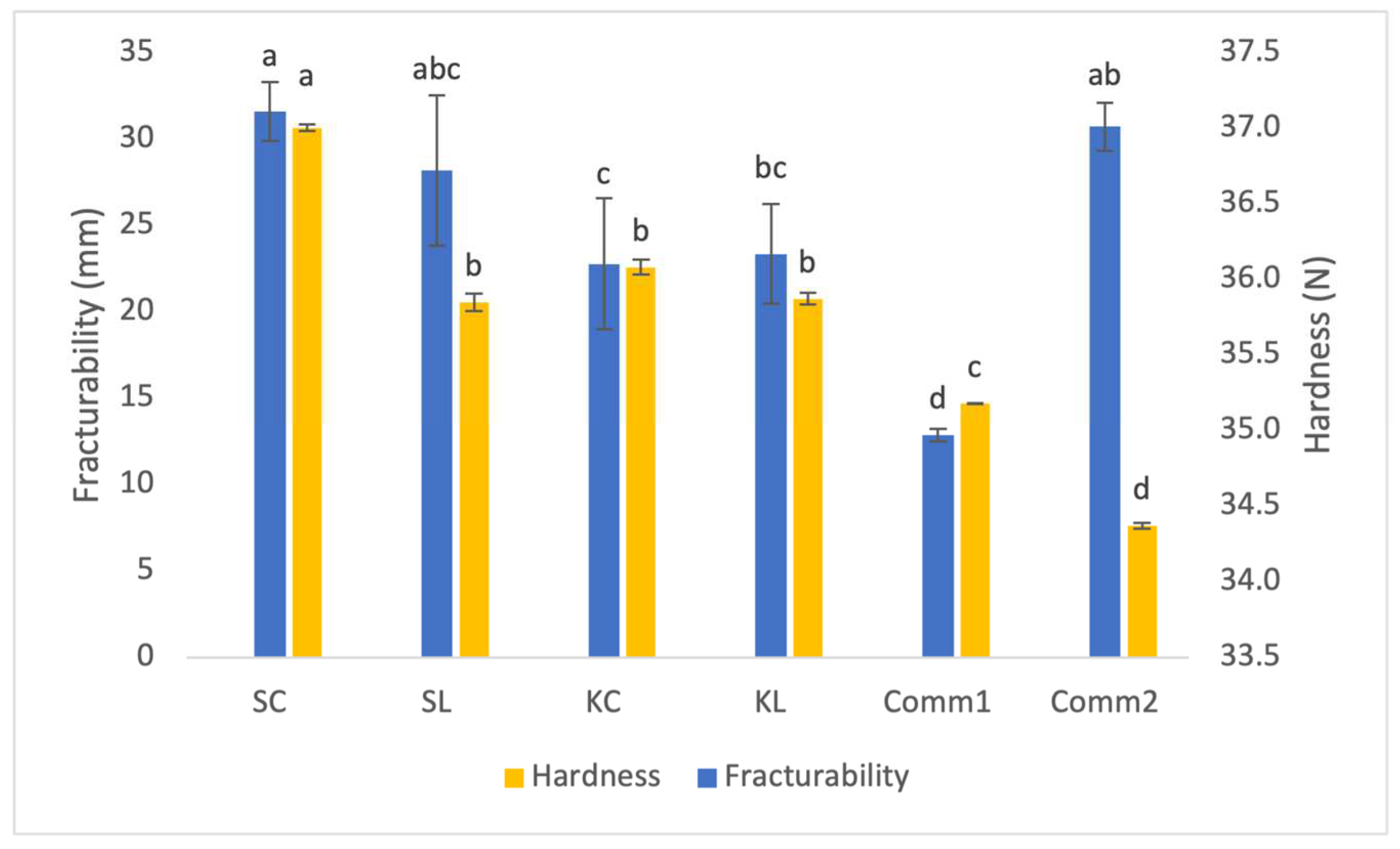

3.3.3. Textural Properties of Cookies

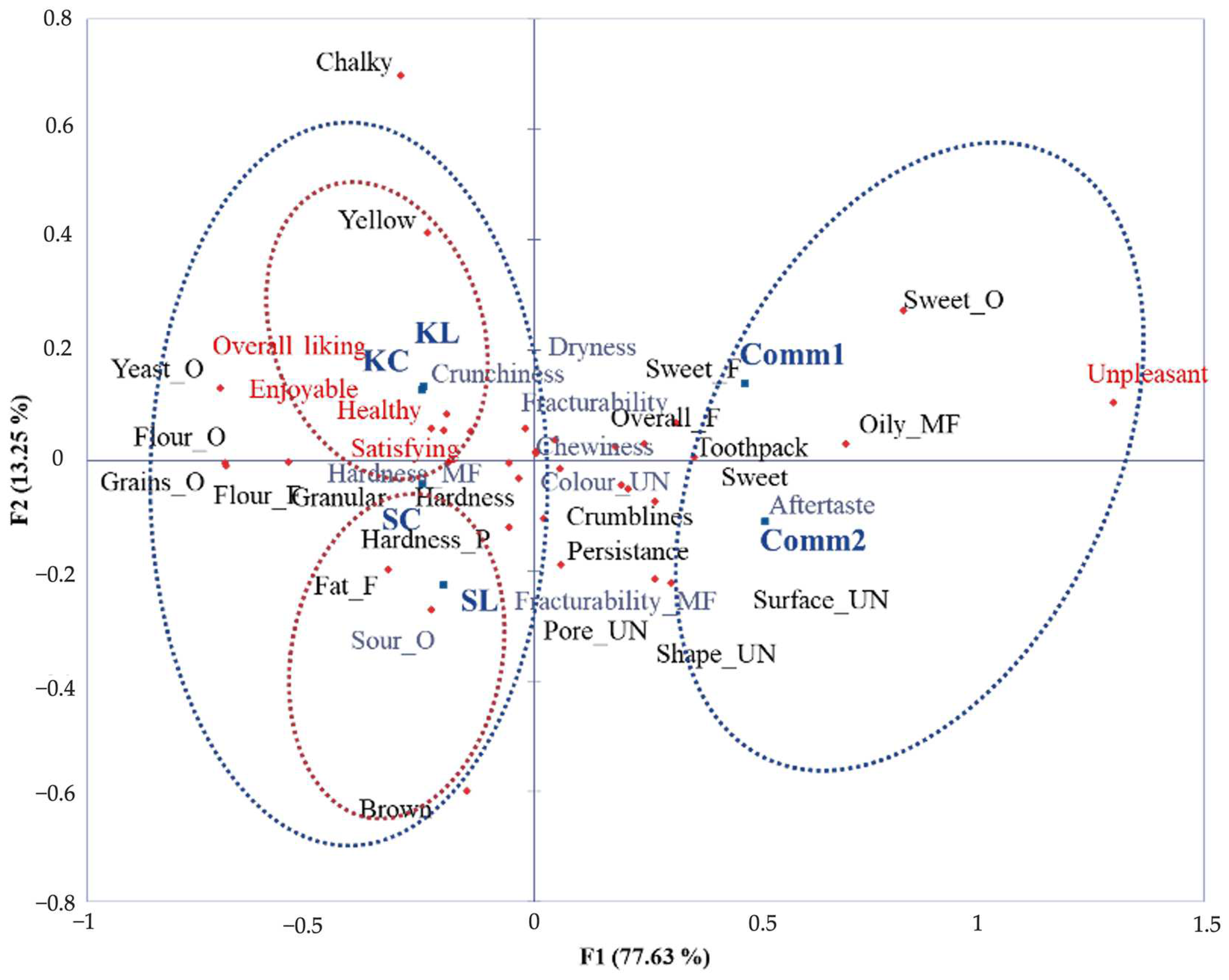

3.3.4. Sensory Analysis of Cookies

4. Conclusions

- Advanced sensory analysis techniques, including Temporal Dominance of Sensations (TDS), Check-All-That-Apply (CATA), and Quantitative Descriptive Analysis (QDA), proved to be effective tools in identifying the most appealing sourdough starters.

- According to these techniques, spelt and Khorasan sourdoughs were selected as the most promising candidates for cookie formulation.

- Sourdough-enriched cookies exhibited comparable nutritional, color, and textural properties to commercial cookies, with a notable increase in fiber content and enhanced sensory appeal.

- Khorasan cookies with lyophilized sourdough starter were considered the most enjoyable, satisfying, and health-promoting option.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Alsubhi, M.; Blake, M.; Nguyen, T.; Majmudar, I.; Moodie, M.; Ananthapavan, J. Consumer Willingness to Pay for Healthier Food Products: A Systematic Review. Obes. Rev. 2023, 24, e13525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoek, A.C.; Pearson, D.; James, S.W.; Lawrence, M.A.; Friel, S. Healthy and Environmentally Sustainable Food Choices: Consumer Responses to Point-of-Purchase Actions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2017, 58, 94–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jovanov, P.; Sakač, M.; Jurdana, M.; Pražnikar, Z.J.; Kenig, S.; Hadnađev, M.; Jakus, T.; Petelin, A.; Škrobot, D.; Marić, A. High-Protein Bar as a Meal Replacement in Elite Sports Nutrition: A Pilot Study. Foods 2021, 10, 2628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boukid, F.; Folloni, S.; Sforza, S.; Vittadini, E.; Prandi, B. Current Trends in Ancient Grains-Based Foodstuffs: Insights into Nutritional Aspects and Technological Applications. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2018, 17, 123–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cappelli, A.; Cini, E.; Guerrini, L.; Masella, P.; Angeloni, G.; Parenti, A. Predictive Models of the Rheological Properties and Optimal Water Content in Doughs: An Application to Ancient Grain Flours with Different Degrees of Refining. J. Cereal Sci. 2018, 83, 229–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katina, K.; Arendt, E.; Liukkonen, K.-H.; Autio, K.; Flander, L.; Poutanen, K. Potential of Sourdough for Healthier Cereal Products. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 16, 104–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Wang, Z.; Guo, X.; Wang, F.; Huang, J.; Sun, B.; Wang, X. Sourdough Improves the Quality of Whole-Wheat Flour Products: Mechanisms and Challenges—A Review. Food Chem. 2021, 360, 130038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salim-ur-Rehman; Paterson, A.; Piggott, J.R. Flavour in Sourdough Breads: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 17, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, A.; Schieberle, P. Generation of Aroma Compounds during Sourdough Fermentation: Applied and Fundamental Aspects. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 16, 85–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pétel, C.; Onno, B.; Prost, C. Sourdough Volatile Compounds and Their Contribution to Bread: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2017, 59, 105–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chavan, R.S.; Chavan, S.R. Sourdough Technology-A Traditional Way for Wholesome Foods: A Review. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2011, 10, 169–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nissar, J.; Ahad, T.; Naik, H.; Hussain, S. A Review Phytic Acid: As Antinutrient or Nutraceutical. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2017, 6, 1554–1560. [Google Scholar]

- Gobbetti, M.; Minervini, F.; Pontonio, E.; Di Cagno, R.; De Angelis, M. Drivers for the Establishment and Composition of the Sourdough Lactic Acid Bacteria Biota. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 239, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvert, M.D.; Madden, A.A.; Nichols, L.M.; Haddad, N.M.; Lahne, J.; Dunn, R.R.; McKenney, E.A. A Review of Sourdough Starters: Ecology, Practices, and Sensory Quality with Applications for Baking and Recommendations for Future Research. PeerJ 2021, 9, e11389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gobbetti, M.; Lavermicocca, P.; Minervini, F.; De Angelis, M.; Corsetti, A. Arabinose Fermentation by Lactobacillus Plantarum in Sourdough with Added Pentosans and Alphaalpha-L-Arabinofuranosidase: A Tool to Increase the Production of Acetic Acid. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2000, 88, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Vuyst, L.; Harth, H.; Van Kerrebroeck, S.; Leroy, F. Yeast Diversity of Sourdoughs and Associated Metabolic Properties and Functionalities. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2016, 239, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Katina, K.; Heiniö, R.-L.; Autio, K.; Poutanen, K. Optimization of Sourdough Process for Improved Sensory Profile and Texture of Wheat Bread. LWT-Food Sci. Technol. 2006, 39, 1189–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hellemann, U.; Powers, J.J.; Salovaara, H.; Shinholser, K.; Ellilä, M. Relation of Sensory Sourness to Chemically Analyzed Acidity in Wholemeal Sour Rye Bread. J. Sens. Stud. 1988, 3, 95–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, J.; Dapčević-Hadnađev, T.; Škrobot, D.; Maravić, N.; Popović, N.; Stevanović, D.; Hadnađev, M. Spontaneously Fermented Ancient Wheat Sourdoughs in Breadmaking: Impact of Flour Quality on Sourdough and Bread Physico-Chemical Properties. LWT 2023, 175, 114482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maravić, N.; Pajin, B.; Hadnađev, M.; Dapčević-Hadnađev, T.; Pestorić, M.; Škrobot, D.; Tomić, J. Assessment of Whole Grain Ancient Wheat Sourdough in Lyophilised and Native Forms for Cookie Formulation. Foods 2024, 13, 3363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pineau, N.; De Bouillé, A.G.; Lepage, M.; Lenfant, F.; Schlich, P.; Martin, N.; Rytz, A. Temporal Dominance of Sensations: What Is a Good Attribute List? Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 26, 159–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Association of Official Analytical Chemists (AOAC). Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International; AOAC: Rockville, MD, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Regulation (EU) No. 1169/2011 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 25 October 2011 on the Provision of Food Information to Consumers, Amending Regulations (EC) No. 1924/2006 and (EC) No. 1925/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council, and Repealing Commission Directive 87/250/EEC, Council Directive 90/496/EEC, Commission Directive 1999/10/EC, Directive 2000/13/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council, Commission Directives 2002/67/EC and 2008/5/EC and Commission Regulation (EC) No. 608/2004. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02011R1169-20180101 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Dharshini, S.S.; Meera, M. Effect of Popping and Milling on Physical, Chemical, Structural, Thermal Properties and Angle of Repose of Amaranth Seed (Amaranthus cruentus L.) and Finger Millet (Eleusine coracana L. Gaertn) from Udhagamandalam. Appl. Food Res. 2023, 3, 100306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramashia, S.E.; Mamadisa, F.M.; Mashau, M.E. Effect of Parinari curatellifolia Peel Flour on the Nutritional, Physical and Antioxidant Properties of Biscuits. Processes 2021, 9, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlich, P. Temporal Dominance of Sensations (TDS): A New Deal for Temporal Sensory Analysis. Curr. Opin. Food Sci. 2017, 15, 38–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salovaara, H.; Valjakka, T. The Effect of Fermentation Temperature, Flour Type, and Starter on the Properties of Sour Wheat Bread. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 1987, 22, 591–597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kati, K.; Kaisa, P.; Karin, A. Influence and Interactions of Processing Conditions and Starter Culture on Formation of Acids, Volatile Compounds, and Amino Acids in Wheat Sourdoughs. Cereal Chem. 2004, 81, 598–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadnađev, M.; Tomić, J.; Škrobot, D.; Dapčević-Hadnađev, T. Rheological Behavior of Emmer, Spelt and Khorasan Flours. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2022, 46, e15873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation (EC) No. 1924/2006 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 20 December 2006 on Nutrition and Health Claims Made on Foods. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/legal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX%3A02006R1924-20141213 (accessed on 10 December 2024).

- Pathare, P.B.; Opara, U.L.; Al-Said, F.A.-J. Colour Measurement and Analysis in Fresh and Processed Foods: A Review. Food Bioprocess Technol. 2013, 6, 36–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jan, K.N.; Panesar, P.S.; Singh, S. Optimization of Antioxidant Activity, Textural and Sensory Characteristics of Gluten-Free Cookies Made from Whole Indian Quinoa Flour. LWT 2018, 93, 573–582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomić, J.; Škrobot, D.; Dapčević-Hadnađev, T.; Maravić, N.; Rakita, S.; Hadnađev, M. Chia Seed Hydrogel as a Solid Fat Replacer and Structure Forming Agent in Gluten-Free Cookies. Gels 2022, 8, 774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manley, D. Biscuit, Cracker and Cookie Recipes for the Food Industry, 1st ed.; Woodhead Publishing Limited: Abington Hall, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Pareyt, B.; Talhaoui, F.; Kerckhofs, G.; Brijs, K.; Goesaert, H.; Wevers, M.; Delcour, J.A. The Role of Sugar and Fat in Sugar-Snap Cookies: Structural and Textural Properties. J. Food Eng. 2009, 90, 400–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevallier, S.; Colonna, P.; Della Valle, G.; Lourdin, D. Contribution of Major Ingredients during Baking of Biscuit Dough Systems. J. Cereal Sci. 2000, 31, 241–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ares, G.; Bruzzone, F.; Vidal, L.; Cadena, R.S.; Giménez, A.; Pineau, B.; Hunter, D.C.; Paisley, A.G.; Jaeger, S.R. Evaluation of a Rating-Based Variant of Check-All-That-Apply Questions: Rate-All-That-Apply (RATA). Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 36, 87–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Ingredients (g/100 g) | Spelt_C | Spelt_L | Khorasan_C | Khorasan_L |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Flour (g) | 100 | 75 | 100 | 75 |

| Sourdough lyophilized (g) | - | 25 | - | 25 |

| Vegetable fat | 20 | 20 | 20 | 20 |

| Sugar | 15 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| NaCl | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 | 0.5 |

| NaHCO3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 | 0.3 |

| NH4HCO3 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| Water | 29.1 | 31.3 | 28.2 | 30.7 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Škrobot, D.; Maravić, N.; Hadnađev, M.; Dapčević-Hadnađev, T.; Pestorić, M.; Tomić, J. Exploring the Sensory Odor Profile of Sourdough Starter from Ancient Whole-Wheat Flours in the Development of Cookies with Enhanced Quality. Foods 2025, 14, 613. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14040613

Škrobot D, Maravić N, Hadnađev M, Dapčević-Hadnađev T, Pestorić M, Tomić J. Exploring the Sensory Odor Profile of Sourdough Starter from Ancient Whole-Wheat Flours in the Development of Cookies with Enhanced Quality. Foods. 2025; 14(4):613. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14040613

Chicago/Turabian StyleŠkrobot, Dubravka, Nikola Maravić, Miroslav Hadnađev, Tamara Dapčević-Hadnađev, Mladenka Pestorić, and Jelena Tomić. 2025. "Exploring the Sensory Odor Profile of Sourdough Starter from Ancient Whole-Wheat Flours in the Development of Cookies with Enhanced Quality" Foods 14, no. 4: 613. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14040613

APA StyleŠkrobot, D., Maravić, N., Hadnađev, M., Dapčević-Hadnađev, T., Pestorić, M., & Tomić, J. (2025). Exploring the Sensory Odor Profile of Sourdough Starter from Ancient Whole-Wheat Flours in the Development of Cookies with Enhanced Quality. Foods, 14(4), 613. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods14040613