Innovation Strategies of the Spanish Agri-Food Sector in Response to the Black Swan COVID-19 Pandemic

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Panic Buying

1.2. The Food Attributes and Situational Factors That Influence Panic Buying

1.3. The Consumer and Panic Buying

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Database

2.2. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Amount Purchased of Different Food Items

3.2. Food Buying and Places of Purchase

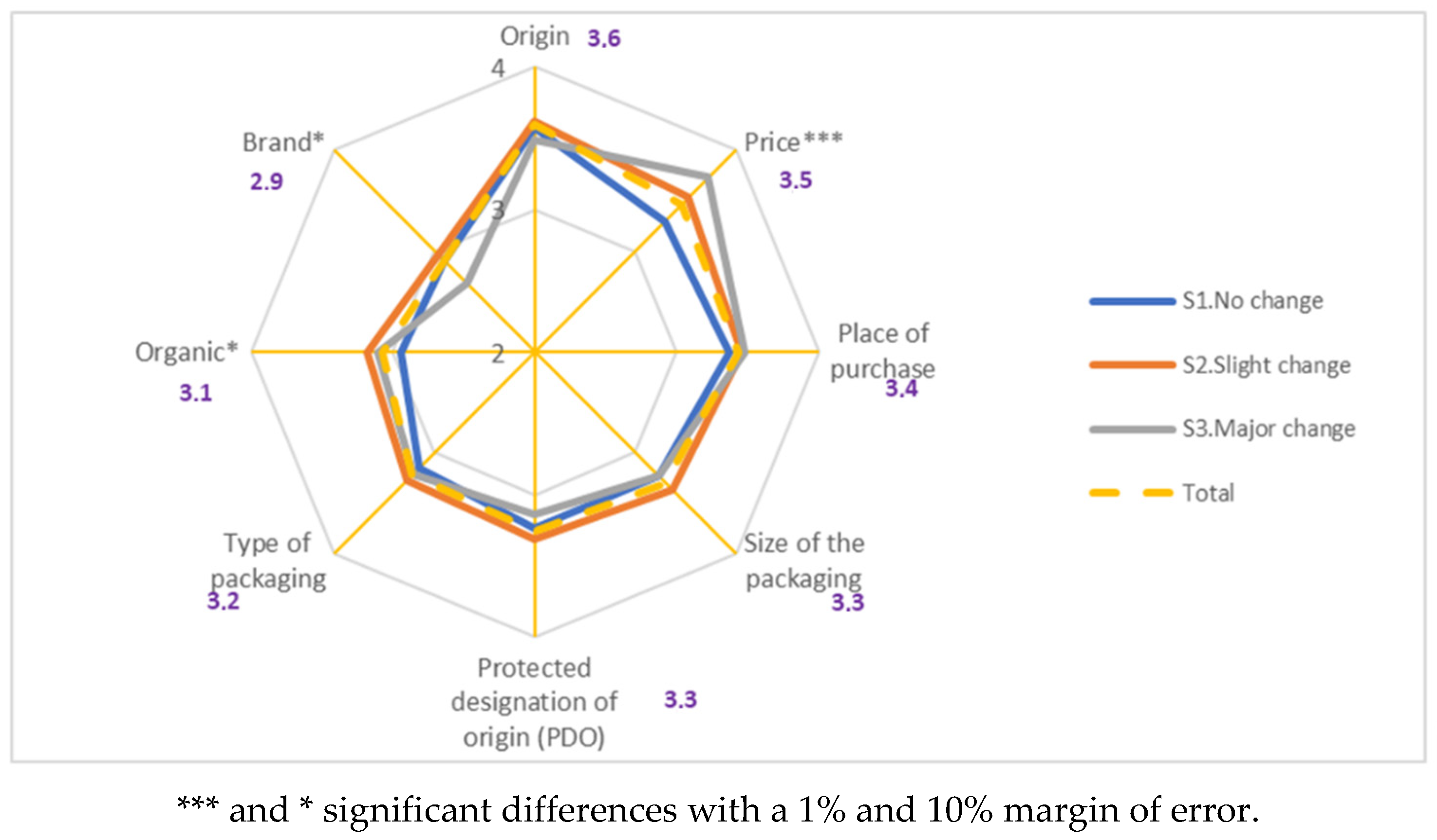

3.3. Purchase Attributes

3.4. Level of Concern for COVID, Impact, and the Search for Information

3.5. Socio-Economic Characteristics of People Polled by Segments

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Taleb, N.N. The Black Swan: The Impact of the Highly Improbable; Random House Publishing Group: New York, NY, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mohan, V.; Berg, C.; Poblet, M. Panic, Information and Quantity Assurance in a Pandemic. Available online: https://ssrncom/abstract=3575232 (accessed on 14 April 2020).

- Nicola, M.; Alsafi, Z.; Sohrabi, C.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, M.; Agha, R. The socio-economic implications of the coronavirus pandemic (COVID-19): A review. Int. Surg. J. 2020, 78, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morse, S.S.; Mazet, J.A.; Woolhouse, M.; Parrish, C.R.; Carroll, D.; Karesh, W.B.; Zambrana-Torrelio, C.; Lipkin, W.I.; Daszak, P. Prediction and prevention of the next pandemic zoonosis. Lancet 2012, 380, 1956–1965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woolhouse, M.; Scott, F.; Hudson, Z.; Howey, R.; Chase-Topping, M. Human viruses: Discovery and emergence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B 2012, 367, 2864–2871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Inayatullah, S. Neither A Black Swan Nor A Zombie Apocalypse: The Futures of a world with the Covid-19 coronavirus. J. Future Stud. 2020, 18. Available online: https://jfsdigital.org/2020/03/18/neither-a-black-swan-nor-a-zombie-apocalypse-the-futures-of-a-world-with-the-covid-19-coronavirus/ (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Raoult, D.; Mouffok, N.; Bitam, I.; Piarroux, R.; Drancourt, M. Plague: History and contemporary analysis. J. Infect. 2013, 66, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horrox, R. The Black Death; Manchester University Press: Manchester, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Geddes, A.M. The history of smallpox. Clin. Dermatol. 2006, 24, 152–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taubenberger, J.K.; Reid, A.H.; Fanning, T.G. The 1918 influenza virus: A killer comes into view. Virol. J. 2000, 274, 241–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- WHO. Global Health Observatory Data. 2019. Available online: https://wwwwhoint/data/gho/data/indicators/indicator-details/GHO/estimated-number-of-people-(all-ages)-living-with-hiv (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Wai Man Fung, O.; Yuen Loke, A. Disaster preparedness of families with young children in Hong Kong. Scand. J. Public Health 2010, 38, 880–888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sohrabi, C.; Alsafi, Z.; O’Neill, N.; Khan, M.; Kerwan, A.; Al-Jabir, A.; Iosifidis, C.; Agha, R. World Health Organization declares global emergency: A review of the 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19). Int. Surg. J. 2020, 76, 71–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, R.M.; Heesterbeek, H.; Klinkenberg, D.; Hollingsworth, T.D. How will country-based mitigation measures influence the course of the COVID-19 epidemic? Lancet 2020, 395, 931–934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunstrom, L.; Newbold, S.; Finnoff, D.; Ashworth, M.; Shogren, J.F. The benefits and costs of flattening the curve for COVID-19 Forthcoming. J. Benefit-Cost Anal. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraemer, M.U.G.; Yang, C.-H.; Gutierrez, B.; Wu, C.-H.; Klein, B.; Pigott, D.M.; du Plessis, L.; Faria, N.R.; Li, R.; Hanage, W.P. The effect of human mobility and control measures on the COVID-19 epidemic in China. Science 2020, 368, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lippi, G.; Henry, B.M.; Bovo, C.; Sanchis-Gomar, F. Health risks and potential remedies during prolonged lockdowns for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Diagnosis 2020, 7, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coetzee, B.J.S.; Kagee, A. Structural barriers to adhering to health behaviors in the context of the COVID-19 crisis: Considerations for low-and middle-income countries. Glob. Public Health 2020, 15, 1093–1102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bracale, R.; Vaccaro, C.M. Changes in food choice following restrictive measures due to Covid-19. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2020, 30, 1423–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, M.C.; Prayag, G.; Fieger, P.; Dyason, D. Beyond panic buying: Consumption displacement and COVID-19. J. Serv. Manag. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jribi, S.; Ben Ismail, H.; Doggui, D.; Debbabi, H. COVID-19 virus outbreak lockdown: What impacts on household food wastage? Environ. Dev. Sustain. 2020, 22, 3939–3955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Carrasco, L.; Brugarolas, M.; del Campo, F.J.; Martínez-Poveda, Á. Influence of purchase place and consumption frequency over quality wine preferences. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 315–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajzen, I.; Fishbein, M. Theory of Reasoned Action-Theory of Planned Behavior; University of South Florida: Tampa, FL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ajzen, I. From Intentions to Actions Attitudes, Personality and Behavior; Dorsey Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Wierenga, B. Model and measurement methodology for the analysis of consumer choice of food products. J. Food Qual. 1983, 6, 119–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yuen, K.F.; Wang, X.; Ma, F.; Li, K.X. The Psychological Causes of Panic Buying Following a Health Crisis. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulam, R.; Furuta, K.; Kanno, T. Development of an agent-based model for the analysis of the effect of consumer panic buying on supply chain disruption due to a disaster. Adv. Model. Simul. Eng. Sci. 2020, 7, 102–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sim, K.; Chua, H.C.; Vieta, E.; Fernandez, G. The anatomy of panic buying related to the current COVID-19 pandemic. Psychiatry Res. 2020, 288, 113015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin-Neuninger, R.; Ruby, M.B. What Does Food Retail Research Tell Us About the Implications of Coronavirus (COVID-19) for Grocery Purchasing Habits? Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurihara, S.; Maruyama, A.; Luloff, A. Analysis of Consumer Behavior in the Tokyo Metropolitan Area after the Great East Japan Earthquake. J. Food Syst. Res. 2012, 18, 415–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez, O.A. The Emergence of Food Panic: Evidence from the Great East Japan Earthquake. J. Disaster Res. 2013, 8, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forbes, S.L. Post-disaster consumption: Analysis from the 2011 Christchurch earthquake. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. Consum. Res. 2017, 27, 28–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G. What’s in a steak? A cross-cultural study on the quality perception of beef? Food Qual. Prefer. 1997, 8, 157–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Olson, J.; Jacoby, J. Cue utilization in the quality perception process. In Proceedings of the Third Annual Conference of the Association for Consumer Research, Chicago, IL, USA, 3–5 November 1972; Venkatesan, M., Ed.; Association for Consumer Research: Chicago, IL, USA, 1972; pp. 167–179. [Google Scholar]

- Vancic, A.; Pärson, G.F.A. Changed Buying Behavior in the COVID-19 Pandemic: The Influence of Price Sensitivity and Perceived Quality. 2020. Available online: https://wwwdiva-portalorg/smash/get/diva2:1453326/FULLTEXT01pdf (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Yangui, W.; Hajtaïeb El Aoud, N. Consumer behavior and the anticipation of a total stockout for a food product: Proposing and validating a theoretical model. Int. Rev. Retail Distrib. 2015, 25, 181–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, R.; Shou, B.; Yang, J. Supply disruption management under consumer panic buying and social learning effects. Omega 2020, in press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsao, Y.C.; Raj, P.V.R.P.; Yu, V. Product substitution in different weights and brands considering customer segmentation and panic buying behavior. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2019, 77, 209–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suri, R.; Monroe, K.B. The effects of time constraints on consumers’ judgments of prices and products. J. Consum. Res. 2003, 30, 92–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, E.S. Unplanned purchasing: Knowledge of shopping environment and time pressure. J. Retail. 1989, 65, 40. [Google Scholar]

- Park, C.W.; Iyer, E.S.; Smith, D.C. The effects of situational factors on in-store grocery shopping behavior: The role of store environment and time available for shopping. J. Consum. Res. 1989, 15, 422–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bialkova, S.; Grunert, K.G.; van Trijp, H. From desktop to supermarket shelf: Eye-tracking exploration on consumer attention and choice. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 81, 103839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laguna, L.; Fiszman, S.; Puerta, P.; Chaya, C.; Tárrega, A. The impact of COVID-19 lockdown on food priorities Results from a preliminary study using social media and an online survey with Spanish consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2020, 86, 104028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hobbs, J.E. Food supply chains during the COVID-19 pandemic. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yoon, J.; Narasimhan, R.; Kim, M.K. Retailer’s sourcing strategy under consumer stockpiling in anticipation of supply disruptions. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2018, 56, 3615–3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frank, B.; Schvaneveldt, S.J. Understanding consumer reactions to product contamination risks after national disasters: The roles of knowledge, experience, and information sources. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2016, 28, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Asmundson, G.J.; Taylor, S. How health anxiety influences responses to viral outbreaks like COVID-19: What all decision-makers, health authorities, and health care professionals need to know. J. Anxiety Disord. 2020, 71, 102211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sneath, J.Z.; Lacey, R.; Kennett-Hensel, P.A. Coping with a natural disaster: Losses, emotions, and impulsive and compulsive buying. Mark. Lett. 2009, 20, 45–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennett-Hensel, P.A.; Sneath, J.Z.; Lacey, R. Liminality and consumption in the aftermath of a natural disaster. J. Consum. Mark. 2012, 29, 52–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- FAO. 2020. Available online: http://wwwfaoorg/2019-ncov/q-and-a/impact-on-food-and-agriculture/en/ (accessed on 10 July 2020).

- Bernués, A.; Ripoll, G.; Panea, B. Consumer segmentation based on convenience orientation and attitudes towards quality attributes of lamb meat. Food Qual. Prefer. 2012, 26, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realini, C.E.; Kallas, Z.; Pérez-Juan, M.; Gómez, I.; Olleta, J.L.; Beriain, M.J.; Albertí, P.; Sañudo, C. Relative importance of cues underlying Spanish consumers’ beef choice and segmentation, and consumer liking of beef enriched with n-3 and CLA fatty acids. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 33, 74–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verain, M.C.; Sijtsema, S.J.; Antonides, G. Consumer segmentation based on food-category attribute importance: The relation with healthiness and sustainability perceptions. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 48, 99–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeithaml, V.A. Consumer perceptions of price, quality and value: A means-end model and synthesis of evidence. J. Mark. 1988, 52, 2–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brunsø, K.; Fjord, T.A.; Grunert, K.G. Consumers’ Food Choice and Quality Perception; The Aarhus School of Business Publ.: Aarhus, Denmark, 2002; pp. 1–60. [Google Scholar]

- Lea, E.; Worsley, T. Australians’ organic food beliefs, demographics and values. Br. Food J. 2005, 107, 855–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Veale, R.; Quester, P. Consumer sensory evaluations of wine quality: The respective influence of price and country of origin. J. Wine Econ. 2008, 3, 10–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Realini, C.E.; i Furnols, M.F.; Sañudo, C.; Montossi, F.; Oliver, M.A.; Guerrero, L. Spanish, French and British consumers’ acceptability of Uruguayan beef, and consumers’ beef choice associated with country of origin, finishing diet and meat price. Meat Sci. 2013, 95, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utami, H.N.; Sadeli, A.H.; Perdana, T. Customer value creation of fresh tomatoes through branding and packaging as customer perceived quality. J. ISSAAS 2016, 22, 123–136. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, L.; Baldin, A. The country of origin effect: A hedonic price analysis of the Chinese wine market. Br. Food J. 2018, 120, 1264–1279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adasme-Berríos, C.; Sánchez, M.; Mora, M.; Díaz, J.; Schnettler, B.; Lobos, G. The gender role on moderator effect of food safety label between perceived quality and risk on fresh vegetables. Rev. Fac. Cienc. Agrar. Univ. Cuyo 2019, 51, 93–109. [Google Scholar]

- Verbeke, W.; Ward, R.W. Consumer interest in information cues denoting quality, traceability and origin: An application of ordered probit models to beef labels. Food Qual. Prefer. 2006, 17, 453–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Roosen, J. Market differentiation potential of country-of-origin, quality and traceability labeling. Estey Cent. J. Int. Law Trade Policy 2009, 10, 20–35. [Google Scholar]

- Bernabéu, R.; Díaz, M.; Olmeda, M. Origin vs organic in Manchego cheese: Which is more important? Br. Food J. 2010, 112, 887–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hersleth, M.; Næs, T.; Rødbotten, M.; Lind, V.; Monteleone, E. Lamb meat-Importance of origin and grazing system for Italian and Norwegian consumers. Meat Sci. 2012, 90, 899–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, K.H.; Hu, W.; Maynard, L.J.; Goddard, E. US consumers’ preference and willingness to pay for country-of-origin-labeled beef steak and food safety enhancements. Can. J. Agric. Econ. 2013, 61, 93–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzmán, A.C.; Schnettler, B.; Mora, M.; Aguilera, M. Perceived quality of and satisfaction from sweet cherries (Prunus avium L.) in China: Confirming relationships through structural equations. J. Agric. Nat. Resour. 2018, 45, 210–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salazar-Ordóñez, M.; Cordón-Pedregosa, R.; Rodríguez-Entrena, M.A. Consumer behavior approach to analyse handmade and locally made agrifood products in Western Honduras. Econ. Agrar. Recur. Nat. 2018, 18, 5–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glitsch, K. Consumer perceptions of fresh meat quality: Cross-national comparison. Br. Food J. 2000, 102, 177–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weatherell, C.; Tregear, A.; Allinson, J. In search of the concerned consumer: UK public perceptions of food, farming and buying local. J. Rural Stud. 2003, 19, 233–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bredahl, L. Cue utilisation and quality perception with regard to branded beef. Food Qual. Prefer. 2004, 15, 65–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verbeke, W.; Vackier, I. Profile and effects of consumer involvement in fresh meat. Meat Sci. 2004, 67, 159–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röhr, A.; Lüddecke, K.; Drusch, S.; Müller, M.J.; Alvensleben, R.V. Food quality and safety—Consumer perception and public health concern. Food Control 2005, 16, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, W.; Maza, M.T.; Mantecón, A.R. Factors that affect and motivate the purchase of quality-labelled beef in Spain. Meat Sci. 2008, 80, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Martínez-Carrasco, L.; Brugarolas, M.; Martínez-Poveda, A.; Ruiz, J.J. Modelling Perceived Quality of Tomato by Structural Equation Analysis. Br. Food J. 2012, 114, 1414–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papanagiotou, P.; Tzimitra-Kalogianni, I.; Melfou, K. Consumers’ expected quality and intention to purchase high quality pork meat. Meat Sci. 2013, 93, 449–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDaniel, C.; Baker, R.C. Convenience food packaging and the perception of product quality. J. Mark. 1977, 41, 57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters-Texeira, A.; Badrie, N. Consumers’ perception of food packaging in Trinidad, West Indies and its related impact on food choices. Int. J. Consum. Stud. 2005, 29, 508–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ampuero, O.; Vila, N. Consumer perceptions of product packaging. J. Consum. Mark. 2006, 23, 100–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussain, S.; Ali, S.; Ibrahim, M.; Noreen, A.; Ahmad, S.F. Impact of product packaging on consumer perception and purchase intention. J. Mark. Consum. Res. 2011, 10, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Magnier, L.; Schoormans, J.; Mugge, R. Judging a product by its cover: Packaging sustainability and perceptions of quality in food products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 53, 132–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lo, S.C.; Tung, J.; Huang, K.P. Customer perception and preference on product packaging International. J. Organ. Innov. 2017, 9, 3–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.S.T. Different effects of utilitarian and hedonic benefits of retail food packaging on perceived product quality and purchase intention. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2017, 23, 239–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benachenhou, S.; Guerrich, B.; Moussaoui, Z. The effect of packaging elements on purchase intention: Case study of Algerian customers. Manag. Sci. Lett. 2018, 8, 217–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahsan Ansari, M.U.; Siddiqui, D.A. Packaging features and consumer buying behavior towards packaged food items. Glob. Sci. J. 2019, 7, 1050–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Becker, T. Consumer perception of fresh meat quality: A framework for analysis. Br. Food J. 2000, 102, 158–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jover, A.J.V.; Montes, F.J.L.; Fuentes, M.D.M.F. Measuring perceptions of quality in food products: The case of red wine. Food Qual. Prefer. 2004, 15, 453–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grunert, K.G. Food quality and safety: Consumer perception and demand. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2005, 32, 369–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaafar, S.N.; Lalp, P.E.; Naba, M.M. Consumers’ perceptions, attitudes and purchase intention towards private label food products in Malaysia. Asian J. Bus. Manag. Sci. 2012, 2, 73–90. [Google Scholar]

- Rubio, N.; Oubina, J.; Villasenor, N. Brand awareness–Brand quality inference and consumer’s risk perception in store brands of food products. Food Qual. Prefer. 2014, 32, 289–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, S.; Rahman, S.U.; Umar, R.M. Measuring customer based beverage brand equity: Investigating the relationship between perceived quality, brand awareness, brand image, and brand loyalty. Int. J. Mark. Stud. 2015, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Toni, D.; Eberle, L.; Larentis, F.; Milan, G.S. Antecedents of perceived value and repurchase intention of organic food. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 24, 456–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susilowati, E.; Sari, A.N. The influence of brand awareness, brand association, and perceived quality toward consumers’purchase intention: A case of richeese factory, Jakarta. Indep. J. Manag. 2020, 11, 39–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larceneux, F.; Benoit-Moreau, F.; Renaudin, V. Why might organic labels fail to influence consumer choices? Marginal labelling and brand equity effects. J. Consum. Policy 2012, 35, 85–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, H.J.; Hwang, J. The driving role of consumers’ perceived credence attributes in organic food purchase decisions: A comparison of two groups of consumers. Food Qual. Prefer. 2016, 54, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konuk, F.A. The role of store image, perceived quality, trust and perceived value in predicting consumers’ purchase intentions towards organic private label food. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 304–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Curvelo, I.C.G.; de Morais Watanabe, E.A.; Alfinito, S. Purchase intention of organic food under the influence of attributes, consumer trust and perceived value. Rev. Gestão 2019, 26, 198–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- John, S.F.; Kumari, R.S.A. Study on Perceived knowledge towards Organic Products. Int. J. Manag. IT Eng. 2019, 7, 158–163. [Google Scholar]

- Bonnet, C.; Simioni, M. Assessing consumer response to Protected Designation of Origin labelling: A mixed multinomial logit approach. Eur. Rev. Agric. Econ. 2001, 28, 433–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sepúlveda, W.S.; Maza, M.T.; Mantecón, Á.R. Factors associated with the purchase of designation of origin lamb meat. Meat Sci. 2010, 85, 167–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- i Furnols, M.F.; Realini, C.; Montossi, F.; Sañudo, C.; Campo, M.M.; Oliver, M.A.; Nute, G.R.; Guerrero, L. Consumer’s purchasing intention for lamb meat affected by country of origin, feeding system and meat price: A conjoint study in Spain, France and United Kingdom. Food Qual. Prefer. 2011, 22, 443–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agnoli, L.; Capitello, R.; Begalli, D. Geographical brand and country-of-origin effects in the Chinese wine import market. J. Brand Manag. 2014, 21, 541–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dias, C.; Mendes, L. Protected designation of origin (PDO), protected geographical indication (PGI) and traditional speciality guaranteed (TSG): A bibliometric analysis. Food Res. Int. 2018, 103, 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, K.E.; Grebitus, C.; Colson, G.; Hu, W. German and British consumer willingness to pay for beef labeled with food safety attributes. J. Agric. Econ. 2017, 68, 451–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lopes, C.; Leitão, J.; Rengifo-Gallego, J. Place branding: Revealing the neglected role of agro food products. Int. Rev. Public Nonprofit Mark. 2018, 15, 497–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, S.E.; López, E.A.C. Los “mundos de producción” de las denominaciones de origen protegidas del vino en España: Disparidad de convenciones tecnológicas y comerciales. Econ. Agrar. Recur. Nat. 2017, 17, 101–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villanueva, J.L.J.; Lázaro, C.E.C.; Ávalos, V.C. Disponibilidad a pagar por atributos culturales en chocolates caseros artesanales de la región de la Chontalpa, Tabasco, México. Econ. Agrar. Recur. Nat. 2018, 18, 53–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kee, H.T.; Wan, D. Intended Usage of Online Supermarkets: The Singapore Case, in ICEB 2004, 1308–1312. Available online: https://pdfssemanticscholarorg/6543/d5abae8db32b9d2975dc020e8bfbe4c1d9ce.pdf (accessed on 15 September 2020).

- Forster, P.W.; Ya, T. The role of online shopping and fulfilment in the Hong Kong SARS crisis. In Proceedings of the 38th Annual Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences, Big Island, HI, USA, 6 January 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AECOC. Consumo y Compra Dentro y Fuera del Hogar Durante y Después del Covid-19. 2020. Available online: https://wwwaecoces/estudio/1er-informe-consumo-y-compra-dentro-y-fuera-del-hogar-durante-y-despues-del-covid-19/ (accessed on 15 July 2020).

- Xie, X.; Huang, L.; Li, J.J.; Zhu, H. Generational Differences in Perceptions of Food Health/Risk and Attitudes toward Organic Food and Game Meat: The Case of the COVID-19 Crisis in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 3148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variables | % |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 32.0 |

| Female | 68.0 |

| Age (in Years) | |

| 18–24 | 5.1 |

| 25–34 | 20.6 |

| 35–49 | 44.5 |

| 50–64 | 26.5 |

| >65 | 3.3 |

| Education Level | |

| Elementary | 2.1 |

| Secondary | 13.6 |

| University | 84.3 |

| Income | |

| <€1000 | 6.4 |

| €1000–€1999 | 30.9 |

| €2000–€2999 | 28.0 |

| €3000–€3999 | 20.3 |

| >€4000 | 14.4 |

| Area of Residence | |

| Rural (<30,000 inhab.) | 19.8 |

| Urban (30,000–100,000 inhab.) | 16.2 |

| High urban population concentration (100,001–500,000 inhab.) | 53.4 |

| Metropolitan area (>500,000 inhab.) | 10.6 |

| Attribute | References |

|---|---|

| Price | [54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61] |

| Origin | [57,58,62,63,64,65,66,67,68] |

| Place of purchase | [69,70,71,72,73,74,75,76] |

| Type and size of packaging | [77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85] |

| Commercial brand | [55,59,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93] |

| Organic certification | [54,55,64,86,92,94,95,96,97,98] |

| Designation of origin (guarantee label) | [63,76,87,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106,107] |

| Food | Seg. 1 No Change (38.6%) 1 | Seg. 2 Slight Change (47.5%) 1 | Seg. 3 Major Change (13.9%) 1 | Total | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rice, pasta, legumes *** | 3.30 | *** | ↓ | 3.52 | ** | ↓ | 3.56 | *** | ↓ | 3.44 | *** | ↓ |

| Dairy products ** | 3.18 | 3.36 | ** | ↑ | 3.37 | 3.29 | ** | ↑ | ||||

| Meat ** | 3.14 | * | ↑ | 3.28 | 3.38 | 3.24 | * | ↑ | ||||

| Fresh fruit and vegetables *** | 3.10 | 3.27 | *** | ↑ | 3.36 | 3.22 | *** | ↑ | ||||

| Baked goods * | 3.12 | 3.21 | *** | ↑ | 3.29 | 3.18 | *** | ↑ | ||||

| Frozen foods | 3.08 | 3.11 | * | ↓ | 3.04 | 3.09 | *** | ↓ | ||||

| Coffee and infusions | 2.98 | 3.06 | 3.04 | ** | ↓ | 3.03 | *** | ↓ | ||||

| Olive oil | 3.00 | * | ↓ | 3.02 | 2.96 | * | ↓ | 3.00 | *** | ↓ | ||

| Fish | 2.99 | ** | ↓ | 2.94 | 2.90 | 2.95 | ** | ↓ | ||||

| Canned food | 2.93 | ** | ↓ | 2.98 | *** | ↓ | 2.93 | ** | ↓ | 2.95 | *** | ↓ |

| Beer, wine, and spirits *** | 2.94 | * | ↑ | 2.93 | 2.59 | 2.89 | ** | ↑ | ||||

| Bottled water | 2.92 | 2.86 | 2.84 | 2.88 | ||||||||

| Snacks * | 2.90 | * | ↑ | 2.92 | * | ↑ | 2.64 | 2.88 | ** | ↑ | ||

| Spices, condiments, and sauces * | 2.77 | 2.76 | 2.55 | ** | ↓ | 2.74 | ** | ↓ | ||||

| Soft drinks and juices *** | 2.71 | 2.76 | 2.33 | 2.68 | ||||||||

| Food Shopping for Home | Seg. 1 (38.6%) 1 | Seg. 2 (47.5%) 1 | Seg. 3 (13.9%) 1 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Buying Food *** | ||||

| Yes, I leave home to shop | 89.2% a | 87.3% a | 72.6% b | 86.0% |

| No, I make a list and a friend/relative brings it to me | 7.8% a | 7.6% a | 9.6% a | 8.0% |

| No, I do it over the Internet | 2.5% a | 3.2% a | 12.3% b | 4.2% |

| No, I do it over the telephone | 0.5% a | 2.0% a,b | 5.5% b | 1.9% |

| Online Food Purchasing (Before the State of Alarm) | ||||

| Never | 63.7% a | 61.0% a | 72.6% a | 63.6% |

| Rarely | 18.6% a | 19.1% a | 8.2% b | 17.4% |

| Sometimes | 15.2% a | 17.5% a | 17.8% a | 16.7% |

| Most of the time | 2.0% a | 1.6% a | 0.0% | 1.5% |

| Always | 0.5% a | 0.8% a | 1.4% a | 0.8% |

| Online Food Purchasing (After the State of Alarm) | 30.40% a | 35.10% a | 47.90% b | 35.00% |

| Consumers that Will Continue Buying Online | ||||

| Definitely not | 33.9% | 27.3% | 45.7% | 33.0% |

| I don’t know | 37.1% | 45.5% | 40.0% | 41.6% |

| Definitely will | 29.0% | 27.3% | 14.3% | 25.4% |

| Place of Purchase | Seg. 1 (38.6%) 1 | Seg. 2 (47.5%) 1 | Seg. 3 (13.9%) 1 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Supermarket/Hypermarket | ||||

| Pre-state of alarm | 4.06 * | 4.05 | 4.21 | 4.08 |

| Post-state of alarm | 4.24 * | 4.06 | 4.03 | 4.12 |

| In Traditional Shops | ||||

| Pre-state of alarm | 2.94 * | 3.13 * | 3.14 * | 3.06 |

| Post-state of alarm | 2.61 * | 2.79 * | 2.71 * | 2.71 |

| In Indoor Markets/Markets | ||||

| Pre-state of alarm *** | 2.15 * | 2.36 * | 2.10 * | 2.24 |

| Post-state of alarm | 1.50 * | 1.73 * | 1.62 * | 1.63 |

| Directly from the Producer | ||||

| Pre-state of alarm | 1.39 * | 1.38 * | 1.34 | 1.38 |

| Post-state of alarm | 1.16 * | 1.21 * | 1.27 | 1.20 |

| Level of Concern and Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic | Seg. 1 (38.6%) 1 | Seg. 2 (47.5%) 1 | Seg. 3 (13.9%) 1 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Level of Concern | ||||

| Not at all concerned | 1.0% | 0.0% | 1.4% | 0.6% |

| Slightly concerned | 2.5% | 0.8% | 1.4% | 1.5% |

| Somewhat concerned | 14.2% | 9.6% | 8.2% | 11.2% |

| Moderately concerned | 32.4% | 36.7% | 28.8% | 33.9% |

| Extremely concerned | 50.0% | 53.0% | 60.3% | 52.8% |

| Impact on the Family Economy *** | ||||

| Very negative | 13.7% a | 24.3% b | 35.6% b | 21.8% |

| Somewhat negative | 55.4% a | 47.0% b | 37.0% b | 48.9% |

| Neutral | 27.9% a | 23.1% a | 20.5% a | 24.6% |

| Somewhat positive | 2.5% a | 4.8% a | 4.1% a | 3.8% |

| Very positive | 0.5% a | 0.8% a | 2.7% a | 0.9% |

| Time and Sources of Information | Seg. 1 (38.6%) 1 | Seg. 2 (47.5%) 1 | Seg. 3 (13.9%) 1 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time Spent Seeking Information (hrs/day) | ||||

| I’m not interested in being informed | 2.5% a | 1.2% a | 0.0% | 1.5% |

| Less than 1 h | 37.3% a | 35.9% a | 35.6%a | 36.4% |

| Between 1 and 2 h | 44.6% a | 40.6% a | 34.2% a | 41.3% |

| Between 2 and 4 h | 9.8% a | 15.5% a,b | 21.9% b | 14.2% |

| More than 4 h | 5.9% a | 6.8% a | 8.2% a | 6.6% |

| Sources of Information | ||||

| TV news *** | 3.49 | 3.70 | 3.36 | 3.57 |

| Newspapers (in paper or online) | 3.29 | 3.49 | 3.45 | 3.41 |

| Relatives and/or friends | 3.11 | 3.22 | 2.99 | 3.15 |

| Official sources *** | 2.95 | 3.18 | 3.29 | 3.10 |

| Social networks | 2.97 | 3.14 | 2.93 | 3.05 |

| Age and Family Size | Seg. 1 (38.6%) 1 | Seg. 2 (47.5%) 1 | Seg. 3 (13.9%) 1 | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in Years) ** | ||||

| 18–24 | 5.4% a,b | 3.6% b | 9.6% a | 5.1% |

| 25–34 | 19.6% a | 17.9% a | 32.9% b | 20.6% |

| 35–49 | 44.6% a | 48.6% a | 30.1% b | 44.5% |

| 50–64 | 25.5% a | 27.9% a | 24.7% a | 26.5% |

| >65 | 4.9% a | 2.0% a | 2.7% a | 3.2% |

| Family Size (members) * | 2.84 | 3.12 | 3.01 | 2.99 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brugarolas, M.; Martínez-Carrasco, L.; Rabadán, A.; Bernabéu, R. Innovation Strategies of the Spanish Agri-Food Sector in Response to the Black Swan COVID-19 Pandemic. Foods 2020, 9, 1821. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9121821

Brugarolas M, Martínez-Carrasco L, Rabadán A, Bernabéu R. Innovation Strategies of the Spanish Agri-Food Sector in Response to the Black Swan COVID-19 Pandemic. Foods. 2020; 9(12):1821. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9121821

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrugarolas, Margarita, Laura Martínez-Carrasco, Adrián Rabadán, and Rodolfo Bernabéu. 2020. "Innovation Strategies of the Spanish Agri-Food Sector in Response to the Black Swan COVID-19 Pandemic" Foods 9, no. 12: 1821. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9121821

APA StyleBrugarolas, M., Martínez-Carrasco, L., Rabadán, A., & Bernabéu, R. (2020). Innovation Strategies of the Spanish Agri-Food Sector in Response to the Black Swan COVID-19 Pandemic. Foods, 9(12), 1821. https://doi.org/10.3390/foods9121821