Power in the Context of SCM and Supply Chain Digitalization: An Overview from a Literature Review

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review: Methodology and Descriptive Analysis

2.1. Methodology

- How is the term of power defined in state-of-the-art research on power within the supply chain?

- How does the existing research capture the impact of power on supply chain management?

- How does the existing research capture the impact of power on the digitalization of the supply chain?

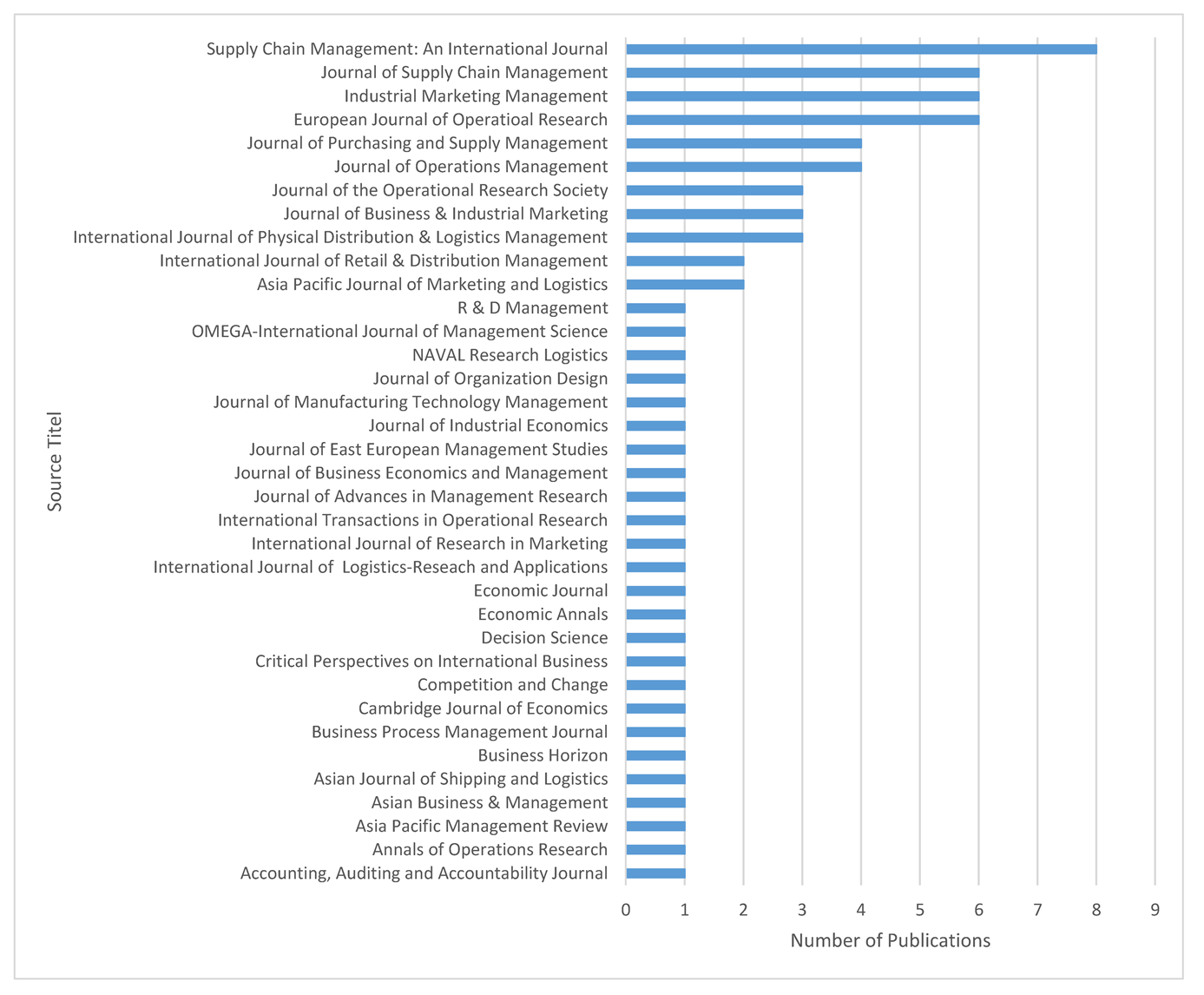

2.2. Descriptive Analysis: Characterising the Research Results and the Literature Surrounding Power in SCM

3. Power within the Supply Chain: An Overview

3.1. Development of a Power Definition Approach in SCM

3.2. Power as a Research Subject in SCM

3.3. Power and Supply Chain Digitalization

4. Concluding Discussion

4.1. Theoretical Implications

4.2. Managerial and Political Implications

4.3. Limitations of the Research

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Review 1 | ||

| Web of Science | Scopus | |

| First research results | 8574 | 22,661 |

| Limitation based on categorizations | 1481 | 953 |

| Limitation based on title and abstract | 68 | 46 |

| Limitation based on accesses and duplicates | 67 | |

| Review 2 | ||

| Web of Science | Scopus | |

| First research results | 2004 | 5872 |

| Limitation based on categorizations | 361 | 240 |

| Limitation based on title and abstract | 3 | 2 |

| Limitation based on accesses and duplicates | 4 | |

| Author | Resource Dependency Theory | Further Influence Strategies |

|---|---|---|

| [76] | X | Transaction Costs Theory |

| [45] | X | |

| [22] | Transaction Cost Theory/Number of Alternatives | |

| [23] | Transaction Costs Theory | |

| [58] | X | Transaction Costs Theory |

| [25] | X | |

| [88] | X | |

| [26] | X | |

| [86] | X | Transaction Costs Theory |

| [65] | X | |

| [81] | ||

| [32] | X | |

| [91] | X | |

| [89] | X | |

| [33] | X | |

| [66] | X | |

| [35] | X | Transaction Costs Theory |

| [36] | X | |

| [24] | X | Transaction Cost Theory/Number of Alternatives |

| [47] | ||

| [74] | X | |

| [63] | X | |

| [82] | X | |

| [38] | X | |

| [64] | X | Transaction Costs Theory |

| [46] | X | |

| [83] | X | |

| [70] | X |

References

- Michalski, M.; Yurov, K.M.; Botella, J.L.M. Trust and IT innovation in asymmetric environments of the supply chain management process. J. Comput. Inf. Syst. 2014, 54, 10–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stank, T.; Esper, T.; Goldsby, T.J.; Zinn, W.; Autry, C. Toward a Digitally Dominant Paradigm for twenty-first century supply chain scholarship. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2019, 49, 956–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofmann, E.; Sternberg, H.; Chen, H.; Pflaum, A.; Prockl, G. Supply chain management and Industry 4.0: Conducting research in the digital age. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2019, 49, 945–955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- International Monetary Fund. World Economic Outlook: Growth Slowdown, Precarious Recovery; International Monetary Fund Cover: Washington, DC, USA, 2019; ISBN 1557757402. [Google Scholar]

- Belaya, V.; Gagalyuk, T.; Hanf, J. Measuring asymmetrical power distribution in supply chain networks: What is the appropriate method? J. Relatsh. Mark. 2009, 8, 165–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnsen, R.E.; Ford, D. Exploring the concept of asymmetry: A typology for analysing customer-supplier relationships. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2008, 37, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Price Waterhouse Coopers Global Top 100 Companies by Market Capitalisation. Available online: https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/audit-services/publications/assets/pwc-global-top-100-companies-2021.pdf (accessed on 20 July 2021).

- Porter, M.E.; Heppelmann, J.E. How smart, connected products are transforming companies. Harv. Bus. Rev. 2015, 114, 96–112. [Google Scholar]

- Reinartz, W.; Wiegand, N.; Imschloss, M. The impact of digital transformation on the retailing value chain. Int. J. Res. Mark. 2019, 36, 350–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vendrell-Herrero, F.; Bustinza, O.F.; Parry, G.; Georgantzis, N. Servitization, digitization and supply chain interdependency. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2017, 60, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grewal, D.S. Network Power: The Social Dynamics of Globalization; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, L.; Yue, X.; Jin, A.; Yen, D.C. Smart supply chain management: A review and implications for future research. Int. J. Logist. Manag. 2016, 27, 395–417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A. Power, value and supply chain management. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 1999, 4, 167–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fink, A. Conducting Research Literature Reviews: From the Internet to Paper, 4th ed.; SAGE Publications: Los Angeles, CA, USA, 2014; ISBN 9781412971898. [Google Scholar]

- Denyer, D.; Tranfield, D. Producing a Systematic Review. In The Sage Handbook of Organizational Research Methods; Buchanan, D., Bryman, A., Eds.; Sage Publications Ltd: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2009; pp. 671–689. ISBN 978-1-4129-3118-2. [Google Scholar]

- French, J.; Raven, B. The bases of social power. In Studies in Social Power; Research Center for Group Dynamics, Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1959; pp. 151–164. [Google Scholar]

- Olsen, M.E.; Marger, M.N. Power in Modern Societies, 1st ed.; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 1993; ISBN 9781000236033. [Google Scholar]

- Popitz, H. Phenomena of Power: Authority, Domination, and Violence; Columbia University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017; ISBN 9780231175944. [Google Scholar]

- Sofsky, W.; Paris, R. Figurationen Sozialer Macht; Leske und Budrich: Opladen, Germany, 1991; ISBN 9780333227794. [Google Scholar]

- El-Ansary, A.I.; Stern, L.W. Power Measurement in the Distribution Channel. J. Mark. Res. 1972, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emerson, R.M. Power-Dependence Relations. Am. Sociol. Assoc. Stable 1962, 27, 31–41. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/208 (accessed on 20 July 2021). [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Benton, W.C.; Maloni, M. The influence of power driven buyer/seller relationships on supply chain satisfaction. J. Oper. Manag. 2005, 23, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingley, M.K. Power imbalanced relationships: Cases from UK fresh food supply. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2005, 33, 551–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takashima, K.; Kim, C. The effectiveness of power-dependence management in retailing. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2016, 44, 71–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crook, T.R.; Combs, J.G. Sources and consequences of bargaining power in supply chains. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 546–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Fedorowicz, J. The role of trust in supply chain governance. Bus. Process Manag. J. 2008, 14, 453–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sucky, E. A bargaining model with asymmetric information for a single supplier-single buyer problem. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2006, 171, 516–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, J.; Wright, G.H. Power priorities: A buyer-seller comparison of areas of influence. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2011, 17, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edirisinghe, N.C.P.; Bichescu, B.; Shi, X. Equilibrium analysis of supply chain structures under power imbalance. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2011, 214, 568–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handley, S.M.; Benton, W.C. Mediated power and outsourcing relationships. J. Oper. Manag. 2012, 30, 253–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mysen, T.; Svensson, G.; Högevold, N. Relationship Quality-Relationship Value and Power Balance in Business Relationships: Descriptives and Propositions. J. Bus. Bus. Mark. 2012, 19, 248–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheu, J.B.; Gao, X.Q. Alliance or no alliance—Bargaining power in competing reverse supply chains. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 233, 313–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazirandeh, A.; Norrman, A. An interrelation model of power and purchasing strategies: A study of vaccine purchase for developing countries. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2014, 20, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maglaras, G.; Bourlakis, M.; Fotopoulos, C. Power-imbalanced relationships in the dyadic food chain: An empirical investigation of retailers’ commercial practices with suppliers. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2015, 48, 187–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorton, M.; Angell, R.; Dries, L.; Urutyan, V.; Jackson, E.; White, J. Power, buyer trustworthiness and supplier performance: Evidence from the Armenian dairy sector. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2015, 50, 69–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sutton-Brady, C.; Kamvounias, P.; Taylor, T. A model of supplier–retailer power asymmetry in the Australian retail industry. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2015, 51, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flynn, B.B.; Zhao, X.; Huo, B.; Yeung, J.H.Y. We’ve got the power! How customer power affects supply chain relationships. Bus. Horiz. 2008, 51, 169–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reimann, F.; Ketchen, D.J. Power in Supply Chain Management. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2017, 53, 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer, J.; Salancik, G.R. The External Control of Organizations: A Resource Dependence Approach; Harper & Row Publisher: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2003; p. 300. [Google Scholar]

- Ireland, P. Satisficing dependent customers: On the power of suppliers in IT systems integration supply chains. Supply Chain Manag. 1999, 4, 184–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A. The art of the possible: Relationship management in power regimes and supply chains. Supply Chain Manag. Int. J. 2004, 9, 346–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matheus, T.; Saunders, M.N.K.; Chakraborty, S. Multiple dimensions of power influencing knowledge integration in supply chains. R D Manag. 2017, 47, 673–688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Mileski, J.P.; Zeng, Q. Alignments between strategic content and process structure: The case of container terminal service process automation. Marit. Econ. Logist. 2019, 21, 543–558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabbri, D.; Klapper, L.F. Bargaining power and trade credit. J. Corp. Financ. 2016, 41, 66–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ireland, P. Managing appropriately in construction power regimes: Understanding the impact of regularity in the project environment. Supply Chain Manag. 2004, 9, 372–382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chicksand, D.; Rehme, J. Total value in business relationships: Exploring the link between power and value appropriation. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2018, 33, 174–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zha, Y.; Yue, X.; Hua, Z. Dominance, bargaining power and service platform performance. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2016, 67, 312–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaudin, G. Vertical Bargaining and Retail Competition: What Drives Countervailing Power? Econ. J. 2018, 128, 2380–2413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Prasad, S.; Shankar, R.; Roy, S. Impact of bargaining power on supply chain profit allocation: A game-theoretic study. J. Adv. Manag. Res. 2019, 16, 398–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Sanderson, J.; Watson, G. Supply chains and power regimes: Toward an analytic framework for managing extended networks of buyer and supplier relationships. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2001, 37, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wang, S.; Chen, L. The role of control power allocation in service supply chains: Model analysis and empirical examination. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2017, 23, 176–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deitz, G.; Hansen, J.; Glenn Richey, R. Coerced integration: The effects of retailer supply chain technology mandates on supplier stock returns. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2009, 39, 814–825. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.C.; Wang, Y.Y.; Lai, F. Impact of power structure on supply chain performance and consumer surplus. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2019, 26, 1752–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, G.; Li, L.; Liu, M.; Sethi, S.P. Impact of power structures in a subcontracting assembly system. Ann. Oper. Res. 2020, 291, 475–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X. Free or bundled: Channel selection decisions under different power structures. Omega 2015, 53, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, W.; Caliskan Demirag, O.; Niu, B. Supply chain performance and consumer surplus under alternative structures of channel dominance. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2014, 239, 130–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, X.; Jiang, X. The impact of power structure on the retail service supply chain with an O2O mixed channel. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2016, 67, 294–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hingley, M.K. Power to all our friends? Living with imbalance in supplier-retailer relationships. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2005, 34, 848–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hubert, F.; Ikonnikova, S. Investment Options and Bargaining Power: The Eurasian Supply Chain for Natural Gas. J. Ind. Econ. 2011, 59, 85–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Reimann, F.; Shen, P.; Kaufmann, L. Effectiveness of power use in buyer-supplier negotiations: The moderating role of negotiator agreeableness. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2016, 46, 932–952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A. Business relationship alignment: On the commensurability of value capture and mutuality in buyer and supplier exchange. Supply Chain Manag. 2004, 9, 410–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hensher, D.A.; Puckett, S.M. Power, concession and agreement in freight distribution chains: Subject to distance-based user charges. Int. J. Logist. Res. Appl. 2008, 11, 81–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huo, B.; Flynn, B.B.; Zhao, X. Supply Chain Power Configurations and Their Relationship with Performance. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2017, 53, 88–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kim, K.T.; Lee, J.S.; Lee, S.Y. The effects of supply chain fairness and the buyer’s power sources on the innovation performance of the supplier: A mediating role of social capital accumulation. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2017, 32, 987–997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sysoiev, V. Optimization models of the supply of power organizational’ structures units with centralized procurement. Econ. Ann. 2013, 58, 137–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Touboulic, A.; Chicksand, D.; Walker, H. Managing Imbalanced Supply Chain Relationships for Sustainability: A Power Perspective. Decis. Sci. 2014, 45, 577–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, S.H.; Seo, Y.W. Effect of supply chain structure and power dynamics on R&D and market performances. J. Bus. Econ. Manag. 2017, 18, 487–504. [Google Scholar]

- Bayne, L.; Purchase, S.; Tarca, A. Power and environmental reporting-practice in business networks. Account. Audit. Account. J. 2019, 32, 632–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaya, V.; Hanf, J.H. Power and conflict in processor-supplier relationships: Empirical evidence from Russian agri-food business. Supply Chain Forum 2014, 15, 60–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bjørgum, Ø.; Aaboen, L.; Fredriksson, A. Low power, high ambitions: New ventures developing their first supply chains. J. Purch. Supply Manag. 2021, 27, 100670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, B.; Cui, Q.; Zhang, J. Impact of channel power and fairness concern on supplier’s market entry decision. J. Oper. Res. Soc. 2017, 68, 1570–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, D.Z.; Cheong, T.; Sun, D. Impact of supply chain power and drop-shipping on a manufacturer’s optimal distribution channel strategy. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 259, 554–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, M.; Ma, S.; Guan, X.; Chen, Y. Channel configuration in a complementary market under different power structures. Nav. Res. Logist. 2021, 68, 157–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandara, S.; Leckie, C.; Lobo, A.; Hewege, C. Power and relationship quality in supply chains: The case of the Australian organic fruit and vegetable industry. Asia Pac. J. Mark. Logist. 2017, 29, 501–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chen, I.J. Mediated power and sustainable supplier management (SSM): Linking power use, justice, and supplier performance. Int. J. Phys. Distrib. Logist. Manag. 2019, 49, 861–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox, A.; Watson, G.; Lonsdale, C.; Sanderson, J. Managing appropriately in power regimes: Relationship and performance management in 12 supply chain cases. Supply Chain Manag. 2004, 9, 357–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.; Gereffi, G. Global value Chains, rising power firms and economic and social upgrading. Crit. Perspect. Int. Bus. 2015, 11, 319–339. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.Y.; Woo, S.H. The Impact of Power on the Relationships and Customer Satisfaction in a Logistics Triad: A Meta-Analysis. Asian J. Shipp. Logist. 2019, 35, 194–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavida, P. From servant to master: Power repositioning of emerging-market companies in global value chains. Asian Bus. Manag. 2015, 15, 292–316. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrobelli, C.; Saliola, F. Power relationships along the value chain: Multinational firms, global buyers and performance of local suppliers. Camb. J. Econ. 2008, 32, 947–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Radaev, V. Market power and relational conflicts in Russian retailing. J. Bus. Ind. Mark. 2013, 28, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brito, R.P.; Miguel, P.L.S. Power, Governance, and Value in Collaboration: Differences between Buyer and Supplier Perspectives. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2017, 53, 61–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Essabbar, D.; Zolghadri, M.; Zrikem, M. A framework to model power imbalance in supply chains: Situational analysis. Asia Pac. Manag. Rev. 2020, 25, 156–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kähkönen, A.K. The influence of power position on the depth of collaboration. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 19, 17–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kähkönen, A.K.; Lintukangas, K.; Hallikas, J. Buyer’s dependence in value creating supplier relationships. Supply Chain Manag. 2015, 20, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nyaga, G.N.; Lynch, D.F.; Marshall, D.; Ambrose, E. Power asymmetry, adaptation and collaboration in dyadic relationships involving a powerful partner. J. Supply Chain Manag. 2013, 49, 42–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Yenipazarli, A. To collaborate or not to collaborate: Prompting upstream eco-efficient innovation in a supply chain. Eur. J. Oper. Res. 2017, 260, 571–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, R.D.; Webb, J.W. A multi-theoretic perspective on trust and power in strategic supply chains. J. Oper. Manag. 2007, 25, 482–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Byrne, R.; Power, D. Exploring agency, knowledge and power in an Australian bulk cereal supply chain: A case study. Supply Chain Manag. 2014, 19, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, M. Digital ecosystems and their implications for competitive strategy. J. Organ. Des. 2020, 9, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belaya, V.; Hanf, J.H. Power and influence in Russian agri-food supply chains: Results of a survey of local subsidiaries of multinational enterprises. J. East Eur. Manag. Stud. 2014, 19, 160–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Power | Supply Chain | Digitalization |

|---|---|---|

| bargaining power | Supply Chain Management | Digitalization |

| customer power | SCM | Innovation |

| buyer power | Supply Chain Relationship | Technology |

| legitimacy | Value Chain | Information |

| reward | Logistics | Automation |

| coercion | ||

| referent | ||

| informational |

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Document type | Journals, conference proceedings | Any other publications, such as reports or reviews |

| Publications stage | Final | Article in process |

| Language | English | Any other language |

| Categories | Keywords | Author |

|---|---|---|

| Bargaining Power in the Supply Chain | Bargaining power; Dominance; Channel coordination; Negotiation; Buyer–supplier negotiation; | [25,27,32,47,48,49,59,60] |

| Power Structures along the Chain | Power Structure; Power dominance; Power Asymmetry; Chain Structure; Business networks; Influence Strategies; Resource Dependence Theory; Control power; Principal–Agent Paradigm | [29,42,45,50,51,52,53,54,61,62,63,64,65,66,67,68,69] |

| Influences of Supply Chain Design on Power Structures | Channel Dominance; Competition; Global sourcing strategy; Relationship initiation; Supplier attractiveness; Supplier selection; Channel selection | [55,56,57,70,71,72,73] |

| Strategies of Power and Supply Chain Relationship Management | Relationship; Relationship marketing; Supplier satisfaction; Power use; Sustainable supplier management; Customer value; Supplier value; Buyer–seller relationships; Channel relationships; Power; Power-imbalanced relationships; Market power; Power-dependence management | [22,24,28,30,33,34,36,37,38,46,58,61,74,75,76,77,78,79,80,81] |

| Collaboration and Power | Collaboration; Contractual Governance; Relational Governance; Supplier relationship; Dependence; Supplier orientation; Logistics triad | [78,82,83,84,85,86,87] |

| Research Focus | Research Gap |

|---|---|

| Generalizable SCM Power Definition | Empirical validation |

| Influence Strategies | Empirical validation of Power bases in SCM |

| Influences of Power on SCM Strategy | Theoretical contributions and empirical validation |

| Similarities of Collaboration/Opportunism and Power research | Theoretical contributions |

| Power and SC digitalization | Theoretical contributions and empirical validation |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Brinker, J.; Haasis, H.-D. Power in the Context of SCM and Supply Chain Digitalization: An Overview from a Literature Review. Logistics 2022, 6, 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics6020025

Brinker J, Haasis H-D. Power in the Context of SCM and Supply Chain Digitalization: An Overview from a Literature Review. Logistics. 2022; 6(2):25. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics6020025

Chicago/Turabian StyleBrinker, Janosch, and Hans-Dietrich Haasis. 2022. "Power in the Context of SCM and Supply Chain Digitalization: An Overview from a Literature Review" Logistics 6, no. 2: 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics6020025

APA StyleBrinker, J., & Haasis, H.-D. (2022). Power in the Context of SCM and Supply Chain Digitalization: An Overview from a Literature Review. Logistics, 6(2), 25. https://doi.org/10.3390/logistics6020025