Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapy in Lung Transplantation

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells

2.1. MSC Surface Receptors and Immunomodulatory Effects

2.2. MSC Secretome and Paracrine Effects

2.3. MSC-Derived Extracellular Vesicles

2.4. MSCs in Lung Injury

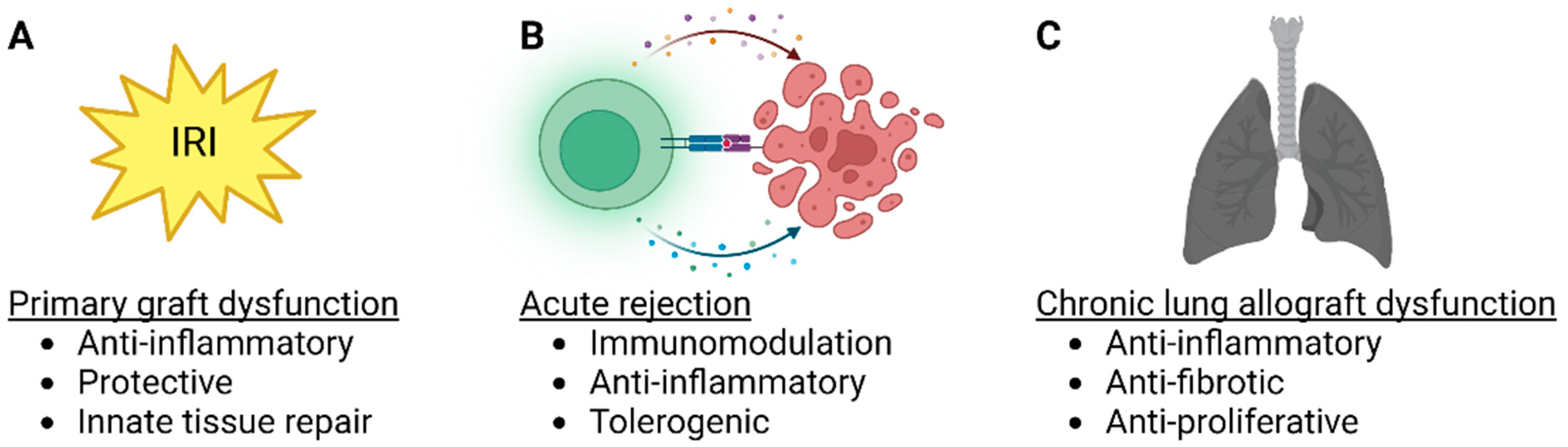

3. Lung Transplant MSC Therapy

3.1. MSC Therapy in Lung Transplant IRI and PGD

3.2. MSC Therapy in Acute Rejection

3.3. MSC Therapy in CLAD

4. Strategies to Improve MSC Delivery and Therapeutic Potential

4.1. MSC Delivery into the Donor Lung during EVLP

4.2. Genetically Engineered MSCs

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chambers, D.C.; Perch, M.; Zuckermann, A.; Cherikh, W.S.; Harhay, M.O.; HayesJr, D.; Hsich, E.; Khush, K.K.; Potena, L.; Sadavarte, A.; et al. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-eighth adult lung transplantation report—2021; Focus on recipient characteristics. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2021, 40, 1060–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chacon-Alberty, L.; Fernandez, R.; Jindra, P.; King, M.; Rosas, I.; Hochman-Mendez, C.; Loor, G. Primary Graft Dysfunction in Lung Transplantation: A Review of Mechanisms and Future Applications. Transplantation 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parulekar, A.D.; Kao, C.C. Detection, classification, and management of rejection after lung transplantation. J. Thorac. Dis. 2019, 11, S1732–S1739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohm, B.; Jungraithmayr, W. B Cell Immunity in Lung Transplant Rejection—Effector Mechanisms and Therapeutic Implications. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 845867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venado, A.; Kukreja, J.; Greenland, J.R. Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction. Thorac. Surg. Clin. 2022, 32, 231–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pittenger, M.F.; Discher, D.E.; Péault, B.M.; Phinney, D.G.; Hare, J.M.; Caplan, A.I. Mesenchymal stem cell perspective: Cell biology to clinical progress. npj Regen. Med. 2019, 4, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Galderisi, U.; Peluso, G.; Di Bernardo, G. Clinical Trials Based on Mesenchymal Stromal Cells are Exponentially Increasing: Where are We in Recent Years? Stem Cell Rev. Rep. 2022, 18, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mansourabadi, A.H.; Mohamed Khosroshahi, L.; Noorbakhsh, F.; Amirzargar, A. Cell therapy in transplantation: A comprehensive review of the current applications of cell therapy in transplant patients with the focus on Tregs, CAR Tregs, and Mesenchymal stem cells. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2021, 97, 107669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandermeulen, M.; Erpicum, P.; Weekers, L.; Briquet, A.; Lechanteur, C.; Detry, O.; Beguin, Y.; Jouret, F. Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in Solid Organ Transplantation. Transplantation 2020, 104, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, V.; Bertani, A. Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells and Their Products as a Therapeutic Tool to Advance Lung Transplantation. Cells 2022, 11, 826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erasmus, D.B.; Durand, N.; Alvarez, F.A.; Narula, T.; Hodge, D.O.; Zubair, A.C. Feasibility and Safety of Low-Dose Mesenchymal Stem Cell Infusion in Lung Transplant Recipients. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2022, 11, 891–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, C.A.; Gonwa, T.A.; Hodge, D.O.; Hei, D.J.; Centanni, J.M.; Zubair, A.C. Feasibility, Safety, and Tolerance of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Obstructive Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 161–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Chambers, D.C.; Enever, D.; Lawrence, S.; Sturm, M.J.; Herrmann, R.; Yerkovich, S.; Musk, M.; Hopkins, P.M. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapy for Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction: Results of a First-in-Man Study. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2017, 6, 1152–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, C.L.; Jane, M.O.; Allan, J.S.; Madsen, J.C. Novel approaches for long-term lung transplant survival. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 931251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niroomand, A.; Hirdman, G.; Olm, F.; Lindstedt, S. Current Status and Future Perspectives on Machine Perfusion: A Treatment Platform to Restore and Regenerate Injured Lungs Using Cell and Cytokine Adsorption Therapy. Cells 2022, 11, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Damasceno, P.K.F.; de Santana, T.A.; Santos, G.C.; Orge, I.D.; Silva, D.N.; Albuquerque, J.F.; Golinelli, G.; Grisendi, G.; Pinelli, M.; Ribeiro dos Santos, R.; et al. Genetic Engineering as a Strategy to Improve the Therapeutic Efficacy of Mesenchymal Stem/Stromal Cells in Regenerative Medicine. Front. Cell Dev. Biol. 2020, 8, 737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Almeida-Porada, G.; Atala, A.J.; Porada, C.D. Therapeutic Mesenchymal Stromal Cells for Immunotherapy and for Gene and Drug Delivery. Mol. Methods Clin. Dev. 2020, 16, 204–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Doherty, D.F.; Roets, L.; Krasnodembskaya, A.D. The Role of Lung Resident Mesenchymal Stromal Cells in the Pathogenesis and Repair of Chronic Lung Disease. Stem Cells 2023, 41, 431–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dominici, M.; Le Blanc, K.; Mueller, I.; Slaper-Cortenbach, I.; Marini, F.; Krause, D.; Deans, R.; Keating, A.; Prockop, D.; Horwitz, E. Minimal criteria for defining multipotent mesenchymal stromal cells. The International Society for Cellular Therapy position statement. Cytotherapy 2006, 8, 315–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, R.S.; Newsome, P.N. A Comparison of Phenotypic and Functional Properties of Mesenchymal Stromal Cells and Multipotent Adult Progenitor Cells. Front. Immunol. 2019, 10, 1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Y.; Yang, J.; Fang, J.; Zhou, Y.; Candi, E.; Wang, J.; Hua, D.; Shao, C.; Shi, Y. The secretion profile of mesenchymal stem cells and potential applications in treating human diseases. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, F.; Li, Y.; Wang, B.; Li, J.; Peng, Z. The safety and efficacy of mesenchymal stromal cells in ARDS: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Crit. Care 2023, 27, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, A.; Zhang, X.; He, H.; Zhou, L.; Naito, Y.; Sugita, S.; Lee, J.W. Therapeutic potential of mesenchymal stem/stromal cell-derived secretome and vesicles for lung injury and disease. Expert Opin. Biol. Ther. 2020, 20, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarvinen, L.; Badri, L.; Wettlaufer, S.; Ohtsuka, T.; Standiford, T.J.; Toews, G.B.; Pinsky, D.J.; Peters-Golden, M.; Lama, V.N. Lung Resident Mesenchymal Stem Cells Isolated from Human Lung Allografts Inhibit T Cell Proliferation via a Soluble Mediator1. J. Immunol. 2008, 181, 4389–4396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Rolandsson, S.; Andersson Sjöland, A.; Brune, J.C.; Li, H.; Kassem, M.; Mertens, F.; Westergren, A.; Eriksson, L.; Hansson, L.; Skog, I.; et al. Primary mesenchymal stem cells in human transplanted lungs are CD90/CD105 perivascularly located tissue-resident cells. BMJ Open Respir. Res. 2014, 1, e000027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jerkic, M.; Szaszi, K.; Laffey, J.G.; Rotstein, O.; Zhang, H. Key Role of Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Interaction with Macrophages in Promoting Repair of Lung Injury. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 3376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, W.; Jiang, J.; Arp, J.; Liu, W.; Garcia, B.; Wang, H. Regulatory T-cell generation and kidney allograft tolerance induced by mesenchymal stem cells associated with indoleamine 2,3-dioxygenase expression. Transplantation 2010, 90, 1312–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasef, A.; Chapel, A.; Mazurier, C.; Bouchet, S.; Lopez, M.; Mathieu, N.; Sensebé, L.; Zhang, Y.; Gorin, N.C.; Thierry, D.; et al. Identification of IL-10 and TGF-beta transcripts involved in the inhibition of T-lymphocyte proliferation during cell contact with human mesenchymal stem cells. Gene Expr. 2007, 13, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gennai, S.; Monsel, A.; Hao, Q.; Park, J.; Matthay, M.A.; Lee, J.W. Microvesicles Derived From Human Mesenchymal Stem Cells Restore Alveolar Fluid Clearance in Human Lungs Rejected for Transplantation. Am. J. Transpl. 2015, 15, 2404–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lonati, C.; Bassani, G.A.; Brambilla, D.; Leonardi, P.; Carlin, A.; Maggioni, M.; Zanella, A.; Dondossola, D.; Fonsato, V.; Grange, C.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell-derived extracellular vesicles improve the molecular phenotype of isolated rat lungs during ischemia/reperfusion injury. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2019, 38, 1306–1316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Worthington, E.N.; Hagood, J.S. Therapeutic Use of Extracellular Vesicles for Acute and Chronic Lung Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 2318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Schmelzer, E.; Miceli, V.; Chinnici, C.M.; Bertani, A.; Gerlach, J.C. Effects of Mesenchymal Stem Cell Coculture on Human Lung Small Airway Epithelial Cells. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 9847579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miceli, V.; Bertani, A.; Chinnici, C.M.; Bulati, M.; Pampalone, M.; Amico, G.; Carcione, C.; Schmelzer, E.; Gerlach, J.C.; Conaldi, P.G. Conditioned Medium from Human Amnion-Derived Mesenchymal Stromal/Stem Cells Attenuating the Effects of Cold Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in an In Vitro Model Using Human Alveolar Epithelial Cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kruk, D.M.L.W.; Wisman, M.; Noordhoek, J.A.; Nizamoglu, M.; Jonker, M.R.; de Bruin, H.G.; Arevalo Gomez, K.; ten Hacken, N.H.T.; Pouwels, S.D.; Heijink, I.H. Paracrine Regulation of Alveolar Epithelial Damage and Repair Responses by Human Lung-Resident Mesenchymal Stromal Cells. Cells 2021, 10, 2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Zheng, R.; Chen, Q.; Shao, J.; Yu, J.; Hu, S. Mesenchymal stem cells microvesicles stabilize endothelial barrier function partly mediated by hepatocyte growth factor (HGF). Stem Cell Res. Ther. 2017, 8, 211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Yan, F. Potential of Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapies for Pulmonary Fibrosis. DNA Cell Biol. 2022, 41, 951–965. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Lu, W.; Ouyang, H.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, C.; Luo, X.; Li, M.; Shu, J.; Zheng, Q.; Chen, H.; et al. Transplantation of Mesenchymal Stem Cells Attenuates Pulmonary Hypertension by Normalizing the Endothelial-to-Mesenchymal Transition. Am. J. Respir. Cell Mol. Biol. 2020, 62, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Park, J.; Liu, A.; Lee, J.; Zhang, X.; Hao, Q.; Lee, J.W. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Microvesicles Restore Protein Permeability Across Primary Cultures of Injured Human Lung Microvascular Endothelial Cells. Stem Cells Transl. Med. 2018, 7, 615–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weiss, D.J.; Rolandsson Enes, S. MSCs interaction with the host lung microenvironment: An overlooked aspect? Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 1072257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nykänen, A.I.; Mariscal, A.; Duong, A.; Estrada, C.; Ali, A.; Hough, O.; Sage, A.; Chao, B.T.; Chen, M.; Gokhale, H.; et al. Engineered mesenchymal stromal cell therapy during human lung ex vivo lung perfusion is compromised by acidic lung microenvironment. Mol. Methods Clin. Dev. 2021, 23, 184–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Francos, S.; Eiro, N.; González-Galiano, N.; Vizoso, F.J. Mesenchymal Stem Cell-Based Therapy as an Alternative to the Treatment of Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome: Current Evidence and Future Perspectives. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 7850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawashima, M.; Juvet, S.C. The role of innate immunity in the long-term outcome of lung transplantation. Ann. Transl. Med. 2020, 8, 412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, E.; Pham, S.; Li, S.; Vazquez-Padron, R.I.; Mathew, J.; Ruiz, P.; Salgar, S.K. Interleukin-10 delivery via mesenchymal stem cells: A novel gene therapy approach to prevent lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. Hum. Gene 2010, 21, 713–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wittwer, T.; Rahmanian, P.; Choi, Y.H.; Zeriouh, M.; Karavidic, S.; Neef, K.; Christmann, A.; Piatkowski, T.; Schnapper, A.; Ochs, M.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell pretreatment of non-heart-beating-donors in experimental lung transplantation. J. Cardiothorac. Surg. 2014, 9, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- La Francesca, S.; Ting, A.E.; Sakamoto, J.; Rhudy, J.; Bonenfant, N.R.; Borg, Z.D.; Cruz, F.F.; Goodwin, M.; Lehman, N.A.; Taggart, J.M.; et al. Multipotent adult progenitor cells decrease cold ischemic injury in ex vivo perfused human lungs: An initial pilot and feasibility study. Transpl. Res. 2014, 3, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- McAuley, D.F.; Curley, G.F.; Hamid, U.I.; Laffey, J.G.; Abbott, J.; McKenna, D.H.; Fang, X.; Matthay, M.A.; Lee, J.W. Clinical grade allogeneic human mesenchymal stem cells restore alveolar fluid clearance in human lungs rejected for transplantation. Am. J. Physiol. Lung Cell Mol. Physiol. 2014, 306, L809–L815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Tian, W.; Liu, Y.; Zhang, B.; Dai, X.; Li, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, Z.; Du, C.; Wang, H. Infusion of mesenchymal stem cells protects lung transplants from cold ischemia-reperfusion injury in mice. Lung 2015, 193, 85–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mordant, P.; Nakajima, D.; Kalaf, R.; Iskender, I.; Maahs, L.; Behrens, P.; Coutinho, R.; Iyer, R.K.; Davies, J.E.; Cypel, M.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cell treatment is associated with decreased perfusate concentration of interleukin-8 during ex vivo perfusion of donor lungs after 18-hour preservation. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2016, 35, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watanabe, T.; Hoshikawa, Y.; Ishibashi, N.; Suzuki, H.; Notsuda, H.; Watanabe, Y.; Noda, M.; Kanehira, M.; Ohkouchi, S.; Kondo, T.; et al. Mesenchymal stem cells attenuate ischemia-reperfusion injury after prolonged cold ischemia in a mouse model of lung transplantation: A preliminary study. Surg. Today 2017, 47, 425–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnapper, A.; Christmann, A.; Knudsen, L.; Rahmanian, P.; Choi, Y.H.; Zeriouh, M.; Karavidic, S.; Neef, K.; Sterner-Kock, A.; Guschlbauer, M.; et al. Stereological assessment of the blood-air barrier and the surfactant system after mesenchymal stem cell pretreatment in a porcine non-heart-beating donor model for lung transplantation. J. Anat. 2018, 232, 283–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, M.L.; Zhao, Y.; Robert Smith, J.; Weiss, M.L.; Kron, I.L.; Laubach, V.E.; Sharma, A.K. Mesenchymal stromal cell-derived extracellular vesicles attenuate lung ischemia-reperfusion injury and enhance reconditioning of donor lungs after circulatory death. Respir. Res. 2017, 18, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martens, A.; Ordies, S.; Vanaudenaerde, B.M.; Verleden, S.E.; Vos, R.; Van Raemdonck, D.E.; Verleden, G.M.; Roobrouck, V.D.; Claes, S.; Schols, D.; et al. Immunoregulatory effects of multipotent adult progenitor cells in a porcine ex vivo lung perfusion model. Stem Cell Res. 2017, 8, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Piatkowski, T.; Brandenberger, C.; Rahmanian, P.; Choi, Y.H.; Zeriouh, M.; Sabashnikov, A.; Wittwer, T.; Wahlers, T.C.W.; Ochs, M.; Mühlfeld, C. Localization of Exogenous Mesenchymal Stem Cells in a Pig Model of Lung Transplantation. Thorac. Cardiovasc. Surg. 2018, 66, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, L.; Han, Z.J.; Xu, L.; Li, J.W. Effect of mesenchymal stem cells on expression of high mobility group box 1 protein in rats with ischemia reperfusion injury after lung transplantation. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2018, 98, 2019–2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakajima, D.; Watanabe, Y.; Ohsumi, A.; Pipkin, M.; Chen, M.; Mordant, P.; Kanou, T.; Saito, T.; Lam, R.; Coutinho, R.; et al. Mesenchymal stromal cell therapy during ex vivo lung perfusion ameliorates ischemia-reperfusion injury in lung transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2019, 38, 1214–1223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacienza, N.; Santa-Cruz, D.; Malvicini, R.; Robledo, O.; Lemus-Larralde, G.; Bertolotti, A.; Marcos, M.; Yannarelli, G. Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy Facilitates Donor Lung Preservation by Reducing Oxidative Damage during Ischemia. Stem Cells Int. 2019, 2019, 8089215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shimoyama, K.; Tsuchiya, T.; Watanabe, H.; Ergalad, A.; Iwatake, M.; Miyazaki, T.; Hashimoto, Y.; Hsu, Y.I.; Hatachi, G.; Matsumoto, K.; et al. Donor and Recipient Adipose-Derived Mesenchymal Stem Cell Therapy for Rat Lung Transplantation. Transpl. Proc. 2022, 54, 1998–2007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.W.; Fang, X.; Gupta, N.; Serikov, V.; Matthay, M.A. Allogeneic human mesenchymal stem cells for treatment of E. coli endotoxin-induced acute lung injury in the ex vivo perfused human lung. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2009, 106, 16357–16362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Lee, J.W.; Krasnodembskaya, A.; McKenna, D.H.; Song, Y.; Abbott, J.; Matthay, M.A. Therapeutic effects of human mesenchymal stem cells in ex vivo human lungs injured with live bacteria. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 187, 751–760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ishibashi, N.; Watanabe, T.; Kanehira, M.; Watanabe, Y.; Hoshikawa, Y.; Notsuda, H.; Noda, M.; Sakurada, A.; Ohkouchi, S.; Kondo, T.; et al. Bone marrow mesenchymal stromal cells protect allograft lung transplants from acute rejection via the PD-L1/IL-17A axis. Surg. Today 2018, 48, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, M.A.; Alanazi, F.; Ahmed, H.A.; Shamma, T.; Kelly, K.; Hammad, M.A.; Alawad, A.O.; Assiri, A.M.; Broering, D.C. iPSC-derived MSC therapy induces immune tolerance and supports long-term graft survival in mouse orthotopic tracheal transplants. Stem Cell Res. 2019, 10, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Grove, D.A.; Xu, J.; Joodi, R.; Torres-Gonzales, E.; Neujahr, D.; Mora, A.L.; Rojas, M. Attenuation of early airway obstruction by mesenchymal stem cells in a murine model of heterotopic tracheal transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2011, 30, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Guo, Z.; Zhou, X.; Li, J.; Meng, Q.; Cao, H.; Kang, L.; Ni, Y.; Fan, H.; Liu, Z. Mesenchymal stem cells reprogram host macrophages to attenuate obliterative bronchiolitis in murine orthotopic tracheal transplantation. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2013, 15, 726–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Casey, A.; Dirks, F.; Liang, O.D.; Harrach, H.; Schuette-Nuetgen, K.; Leeman, K.; Kim, C.F.; Gerard, C.; Subramaniam, M. Bone marrow-derived multipotent stromal cells attenuate inflammation in obliterative airway disease in mouse tracheal allografts. Stem Cells Int. 2014, 2014, 468927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Diamond, J.M.; Arcasoy, S.; Kennedy, C.C.; Eberlein, M.; Singer, J.P.; Patterson, G.M.; Edelman, J.D.; Dhillon, G.; Pena, T.; Kawut, S.M.; et al. Report of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation Working Group on Primary Lung Graft Dysfunction, part II: Epidemiology, risk factors, and outcomes-A 2016 Consensus Group statement of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2017, 36, 1104–1113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Raemdonck, D.; Hartwig, M.G.; Hertz, M.I.; Davis, R.D.; Cypel, M.; Hayes, D., Jr.; Ivulich, S.; Kukreja, J.; Lease, E.D.; Loor, G.; et al. Report of the ISHLT Working Group on primary lung graft dysfunction Part IV: Prevention and treatment: A 2016 Consensus Group statement of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2017, 36, 1121–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenheck, J.; Pietras, C.; Cantu, E. Early Graft Dysfunction after Lung Transplantation. Curr. Pulmonol. Rep. 2018, 7, 176–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diamond, J.M.; Lee, J.C.; Kawut, S.M.; Shah, R.J.; Localio, A.R.; Bellamy, S.L.; Lederer, D.J.; Cantu, E.; Kohl, B.A.; Lama, V.N.; et al. Clinical risk factors for primary graft dysfunction after lung transplantation. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013, 187, 527–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Daud, S.A.; Yusen, R.D.; Meyers, B.F.; Chakinala, M.M.; Walter, M.J.; Aloush, A.A.; Patterson, G.A.; Trulock, E.P.; Hachem, R.R. Impact of immediate primary lung allograft dysfunction on bronchiolitis obliterans syndrome. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2007, 175, 507–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keller, M.; Bush, E.; Diamond, J.M.; Shah, P.; Matthew, J.; Brown, A.W.; Sun, J.; Timofte, I.; Kong, H.; Tunc, I.; et al. Use of donor-derived-cell-free DNA as a marker of early allograft injury in primary graft dysfunction (PGD) to predict the risk of chronic lung allograft dysfunction (CLAD). J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2021, 40, 488–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forgie, K.A.; Fialka, N.; Freed, D.H.; Nagendran, J. Lung Transplantation, Pulmonary Endothelial Inflammation, and Ex-Situ Lung Perfusion: A Review. Cells 2021, 10, 1417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talaie, T.; DiChiacchio, L.; Prasad, N.K.; Pasrija, C.; Julliard, W.; Kaczorowski, D.J.; Zhao, Y.; Lau, C.L. Ischemia-reperfusion Injury in the Transplanted Lung: A Literature Review. Transplant. Direct 2021, 7, e652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Todd, J.L.; Palmer, S.M. Danger signals in regulating the immune response to solid organ transplantation. J. Clin. Investig. 2017, 127, 2464–2472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Iske, J.; Hinze, C.A.; Salman, J.; Haverich, A.; Tullius, S.G.; Ius, F. The potential of ex vivo lung perfusion on improving organ quality and ameliorating ischemia reperfusion injury. Am. J. Transpl. 2021, 21, 3831–3839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen-Yoshikawa, T.F. Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury in Lung Transplantation. Cells 2021, 10, 1333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shepherd, H.M.; Gauthier, J.M.; Terada, Y.; Li, W.; Krupnick, A.S.; Gelman, A.E.; Kreisel, D. Updated Views on Neutrophil Responses in Ischemia-Reperfusion Injury. Transplantation 2022, 106, 2314–2324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calabrese, D.R.; Aminian, E.; Mallavia, B.; Liu, F.; Cleary, S.J.; Aguilar, O.A.; Wang, P.; Singer, J.P.; Hays, S.R.; Golden, J.A.; et al. Natural killer cells activated through NKG2D mediate lung ischemia-reperfusion injury. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e137047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thompson, E.R.; Connelly, C.; Ali, S.; Sheerin, N.S.; Wilson, C.H. Cell therapy during machine perfusion. Transpl. Int. 2021, 34, 49–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chambers, D.C.; Cherikh, W.S.; Harhay, M.O.; Hayes, D., Jr.; Hsich, E.; Khush, K.K.; Meiser, B.; Potena, L.; Rossano, J.W.; Toll, A.E.; et al. The International Thoracic Organ Transplant Registry of the International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation: Thirty-sixth adult lung and heart-lung transplantation Report-2019; Focus theme: Donor and recipient size match. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2019, 38, 1042–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinu, T.; Pavlisko, E.N.; Chen, D.F.; Palmer, S.M. Acute allograft rejection: Cellular and humoral processes. Clin. Chest Med. 2011, 32, 295–310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotecha, S.; Ivulich, S.; Snell, G. Review: Immunosuppression for the lung transplant patient. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021, 13, 6628–6644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauthier, J.M.; Li, W.; Hsiao, H.M.; Takahashi, T.; Arefanian, S.; Krupnick, A.S.; Gelman, A.E.; Kreisel, D. Mechanisms of Graft Rejection and Immune Regulation after Lung Transplant. Ann. Am. Thorac. Soc. 2017, 14, S216–S219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gelman, A.E.; Li, W.; Richardson, S.B.; Zinselmeyer, B.H.; Lai, J.; Okazaki, M.; Kornfeld, C.G.; Kreisel, F.H.; Sugimoto, S.; Tietjens, J.R.; et al. Cutting edge: Acute lung allograft rejection is independent of secondary lymphoid organs. J. Immunol. 2009, 182, 3969–3973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shi, T.; Roskin, K.; Baker, B.M.; Woodle, E.S.; Hildeman, D. Advanced Genomics-Based Approaches for Defining Allograft Rejection With Single Cell Resolution. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 750754. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verleden, S.E.; Vos, R.; Verleden, G.M. Chronic lung allograft dysfunction: Light at the end of the tunnel? Curr. Opin. Organ Transplant. 2019, 24, 318–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verleden, G.M.; Vos, R.; Vanaudenaerde, B.; Dupont, L.; Yserbyt, J.; Van Raemdonck, D.; Verleden, S. Current views on chronic rejection after lung transplantation. Transpl. Int. 2015, 28, 1131–1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sato, M.; Waddell, T.K.; Wagnetz, U.; Roberts, H.C.; Hwang, D.M.; Haroon, A.; Wagnetz, D.; Chaparro, C.; Singer, L.G.; Hutcheon, M.A.; et al. Restrictive allograft syndrome (RAS): A novel form of chronic lung allograft dysfunction. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2011, 30, 735–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Verleden, G.M.; Glanville, A.R.; Lease, E.D.; Fisher, A.J.; Calabrese, F.; Corris, P.A.; Ensor, C.R.; Gottlieb, J.; Hachem, R.R.; Lama, V.; et al. Chronic lung allograft dysfunction: Definition, diagnostic criteria, and approaches to treatment-A consensus report from the Pulmonary Council of the ISHLT. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2019, 38, 493–503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Glanville, A.R.; Verleden, G.M.; Todd, J.L.; Benden, C.; Calabrese, F.; Gottlieb, J.; Hachem, R.R.; Levine, D.; Meloni, F.; Palmer, S.M.; et al. Chronic lung allograft dysfunction: Definition and update of restrictive allograft syndrome-A consensus report from the Pulmonary Council of the ISHLT. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2019, 38, 483–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bedair, B.; Hachem, R.R. Management of chronic rejection after lung transplantation. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021, 13, 6645–6653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bos, S.; Filby, A.J.; Vos, R.; Fisher, A.J. Effector immune cells in chronic lung allograft dysfunction: A systematic review. Immunology 2022, 166, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royer, P.J.; Olivera-Botello, G.; Koutsokera, A.; Aubert, J.D.; Bernasconi, E.; Tissot, A.; Pison, C.; Nicod, L.; Boissel, J.P.; Magnan, A. Chronic Lung Allograft Dysfunction: A Systematic Review of Mechanisms. Transplantation 2016, 100, 1803–1814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Watanabe, T.; Cypel, M.; Keshavjee, S. Ex vivo lung perfusion. J. Thorac. Dis. 2021, 13, 6602–6617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cypel, M.; Yeung, J.C.; Liu, M.; Anraku, M.; Chen, F.; Karolak, W.; Sato, M.; Laratta, J.; Azad, S.; Madonik, M.; et al. Normothermic ex vivo lung perfusion in clinical lung transplantation. N. Engl. J. Med. 2011, 364, 1431–1440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tikkanen, J.M.; Cypel, M.; Machuca, T.N.; Azad, S.; Binnie, M.; Chow, C.W.; Chaparro, C.; Hutcheon, M.; Yasufuku, K.; de Perrot, M.; et al. Functional outcomes and quality of life after normothermic ex vivo lung perfusion lung transplantation. J. Heart Lung Transpl. 2015, 34, 547–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Divithotawela, C.; Cypel, M.; Martinu, T.; Singer, L.G.; Binnie, M.; Chow, C.W.; Chaparro, C.; Waddell, T.K.; de Perrot, M.; Pierre, A.; et al. Long-term Outcomes of Lung Transplant With Ex Vivo Lung Perfusion. JAMA Surg. 2019, 154, 1143–1150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Islam, D.; Huang, Y.; Fanelli, V.; Delsedime, L.; Wu, S.; Khang, J.; Han, B.; Grassi, A.; Li, M.; Xu, Y.; et al. Identification and Modulation of Microenvironment is Crucial for Effective MSC Therapy in Acute Lung Injury. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2019, 199, 1214–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Lv, D.; Zhang, X.; Ni, Z.A.; Sun, X.; Zhu, C. Interleukin-10-Overexpressing Mesenchymal Stromal Cells Induce a Series of Regulatory Effects in the Inflammatory System and Promote the Survival of Endotoxin-Induced Acute Lung Injury in Mice Model. DNA Cell Biol. 2018, 37, 53–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Target | Species | Model | MSC | Administration | Effect | Ref |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IRI | Rat | Lung hilar clamping | Engineered BM-MSC (MSC-vIL-10) | Intravenous | Improved oxygenation, inflammation and permeability | [43] |

| IRI | Pig | SLTx | BM-MSC | Pulmonary artery vs. endobronchial | Endobronchial MSC delivery improved lung compliance | [44] |

| IRI | Human | EVLP | MAPC | Airways | Decreased edema and inflammation | [45] |

| IRI | Human | EVLP | BM-MSC | Intravascular | Restored alveolar fluid clearance | [46] |

| IRI | Mouse | SLTx | BM-MSC | Recipient intravenous | Decreased IRI, MSC homing preferentially into the lung transplant | [47] |

| IRI | Pig | EVLP | UC-MSC | Airway vs. intravascular, 3 different doses | Intravascular delivery improved MSC lung retention, optimal dose 150 × 106 MSC decreased IL-8 and increased VEGF | [48] |

| IRI | Mouse | SLTx | BM-MSC | Ex vivo pulmonary artery | Decreased IRI | [49] |

| IRI | Pig | SLTx | BM-MSC | Pulmonary artery vs. endobronchial | No short-term differences detected | [50] |

| IRI | Mouse | Lung hilar clamping and EVLP | Human UC-MSC vs. MSC-EVs | Intravascular | MSCs and MSC-EVs attenuate IRI | [51] |

| IRI | Human | EVLP | MAPC | Airways | Decreased BAL neutrophilia, TNF-α, IL-1β and IFN-γ | [52] |

| IRI | Pig | SLTx | BM-MSC | Intravenous or intrabronchial | Heterogenous localization, in alveoli after endobronchial and in blood vessels after intravascular administration | [53] |

| IRI | Rat | SLTx | BM-MSC | Intravenous | Protection against IRI | [54] |

| IRI | Pig | EVLP and SLTx | UC-MSC | Intravascular | Decreased IRI during EVLP and after TX | [55] |

| IRI | Rat | EVLP | UC-MSC | Intravascular | Improved inflammation and IRI | [56] |

| IRI | Rat | EVLP | BM-MSC-EVs | Intravascular | Multiple influences on pulmonary energetics, tissue integrity and gene expression | [30] |

| IRI | Human | EVLP | Engineered UC-MSC (MSCIL−10) | Intravascular | Safe and feasible, results in rapid IL-10 elevation | [40] |

| IRI | Rat | SLTx | Donor vs. recipient adipose tissue MSC | Intravenous | MSCs, regardless of their origin, exert similar immunosuppressive effects | [57] |

| IRI/ ARDS | Human | EVLP/endotoxin | BM-MSC | Airways | Restored alveolar fluid clearance | [58] |

| IRI/ ARDS | Human | EVLP/e.coli pneumonia | BM-MSC | Airways | Restored alveolar fluid clearance, reduced inflammation and increased antimicrobial activity | [59] |

| Acute rejection | Rat | SLTx | BM-MSC | 1 vs. 2 recipient intravenous doses | Protection from acute rejection, best result with 2 recipient doses | [60] |

| Acute rejection/ CLAD | Mouse | Ortotopic tracheal Tx | iPSC-MSC | Intravascular | Induces immune tolerance and supports long-term graft survival | [61] |

| CLAD | Mouse | Heterotopic tracheal Tx | MSC (various sources) | Intravenous | Prevents airway occlusion | [62] |

| CLAD | Mouse | Ortotopic tracheal Tx | BM-MSC | Intravenous | Prevents airway occlusion through macrophage cytokines | [63] |

| CLAD | Mouse | Heterotopic tracheal Tx | BM-MSC | Local vs. systemic vs. combination | Prevents airway occlusion through modulation of immune response, best effect with combination treatment | [64] |

| CLAD | Human | Clinical Tx | BM-MSC | Intravenous twice weekly for 2 weeks | Safe and feasible in patients with advanced CLAD | [13] |

| CLAD | Human | Clinical Tx | BM-MSC | Intravenous | Safe and feasible in patients with moderate CLAD | [12] |

| CLAD | Human | Clinical Tx | BM-MSC | Intravenous | Well tolerated in moderate-to-severe CLAD, low-dose may slow progression of CLAD in some patients | [11] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nykänen, A.I.; Liu, M.; Keshavjee, S. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapy in Lung Transplantation. Bioengineering 2023, 10, 728. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering10060728

Nykänen AI, Liu M, Keshavjee S. Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapy in Lung Transplantation. Bioengineering. 2023; 10(6):728. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering10060728

Chicago/Turabian StyleNykänen, Antti I., Mingyao Liu, and Shaf Keshavjee. 2023. "Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapy in Lung Transplantation" Bioengineering 10, no. 6: 728. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering10060728

APA StyleNykänen, A. I., Liu, M., & Keshavjee, S. (2023). Mesenchymal Stromal Cell Therapy in Lung Transplantation. Bioengineering, 10(6), 728. https://doi.org/10.3390/bioengineering10060728