Abstract

We present AΜAΛΘΕΙA (AMALTHIA), an application ontology that models the domain of dishes as they are presented in 112 menus collected from restaurants/taverns/patisseries in East Macedonia and Thrace in Northern Greece. AΜAΛΘΕΙA supports a tourist mobile application offering multilingual translation of menus, dietary and cultural information about the dishes and their ingredients, as well as information about the geographical dispersion of the dishes. In this document, we focus on the food/dish dimension that constitutes the ontology’s backbone. Its dish-oriented perspective differentiates AΜAΛΘΕΙA from other food ontologies and thesauri, such as Langual, enabling it to codify information about the dishes served, particularly considering the fact that they are subject to wide variation due to the inevitable evolution of recipes over time, to geographical and cultural dispersion, and to the chef’s creativity. We argue for the adopted design decisions by drawing on semantic information retrieved from the menus, as well as other social and commercial facts, and compare AMAΛΘΕΙA with other important taxonomies in the food field. To the best of our knowledge, AΜAΛΘΕΙA is the first ontology modeling (i) dish variation and (ii) Greek (commercial) cuisine (a component of the Mediterranean diet).

1. Introduction

It is the menu aspect that makes AΜAΛΘΕΙA special (Amalthia: Baby Zeus’ foster mother, often represented as a goat; see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amalthea_(mythology) (accessed on 10 April 2021)). Dishes, which are the entities dominating the contents of menus, are ever-evolving human creations that satisfy biological and social needs [1,2]. Most existing food thesauri and ontologies have not been concerned with the particularities of dishes as they have predominantly been used to model the industrial food domain, often in a field-to-fork fashion [3,4]. Restaurant customers focus on the quality of the ingredients, cooking details, and social aspects of a dish [5], while industrial food product consumers focus instead on the standardization of the ingredients and their processing. On the other hand, dishes and industrial food products constitute overlapping semantic domains; for instance, they share most of their ingredient sources.

The picture emerging from the menus is that of a dynamic linguistic and conceptual domain with no central organization [6]: terminology is only relatively fixed; dishes are not classified in a uniform way across menus, and contradictory criteria are probably used for the classification of dishes in the menus; the same dish may vary from place to place and from restaurant to restaurant; traditional dish names are used creatively in a continuous evolution of the recipe. In fact, dish variation is a remarkable phenomenon due to reasons such as the geographical and cultural dispersion of a dish, the inevitable evolution of a recipe over time, the chef’s creativity, and the fact that restaurants must abide by the cooking traditions of a specific area and, at the same time, provide unique culinary experiences.

Despite these difficulties, we have resolved to represent in our ontology the picture that emerges from the menus rather than simplifying or idealizing it; after all, this is the material used in everyday practice which reveals the complex semantics of the served food as it is defined and used by the people involved in it. Here are some real cases showing why the classification exercise is challenging:

μακαρόνια με κιμά “spaghetti Bolognese” is listed in menus under both “minced meat dishes” and “pasta dishes”, suggesting that classification by main ingredient (MI) may lead to equally plausible choices.

τηγανητές πατάτες “French fries” is listed in menus both as an appetizer and as a side dish, suggesting that classification by function of the dish in the meal may reveal different ways of viewing meal organization.

The ceremonial dish μαγειρίτσα (magiritsa), which is found all over Greece, is typically made using a suckling lamb’s entrails, them being the main ingredient (MI) of the dish; however, it can also be made with kid goat entrails or a mixture of the two types of meat. Neither of these approaches is traditionally compulsory in order to identify a “magiritsa” dish, but either can be used. In a nutshell, two different ingredients (albeit of the same type) represent equally plausible MIs for the same dish.

Recently, a dish with mushrooms instead of meat was introduced as a “vegetarian magiritsa”; the name of the dish has been retained, although its MI has changed radically.

The phenomenon of synecdoche, whereby a part of an object lends its name to the whole, is pervasive with food names. Very often, the name of the MI and the name of the dish are identical, which may also be true for the name of the MI and its source, e.g., φακή (“lentils”) refers to the name of the plant, the MI, and a typical Greek soup.

In this study, we argue for the entities and the relations we have defined; as such, we consult a detailed linguistic analysis of the dish names extracted from our menu corpus [6]. We place special emphasis on the treatment of the phenomenon of dish variation, we model the arrangement of ingredients in dishes, we evaluate our approach, and we conclude with future plans considering the development of the ontology.

2. Materials and Methods

We draw on a collection of 112 menus from Thrace and Eastern Macedonia collected manually from restaurants, taverns, and patisseries that do not specialize in food delivery and, in general, do not publish their material on the web; these are precisely the food-serving shops that are of interest to visitors of the area. This collection of menus depicts the particular gastronomic market quite well, and it is unique in its kind.

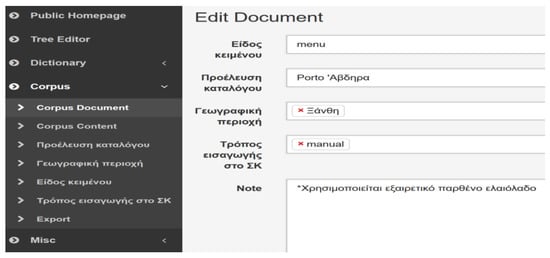

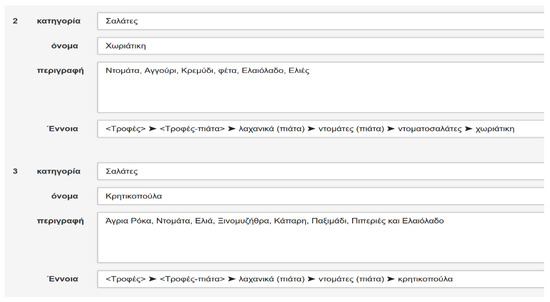

Menu texts were stored manually on a web database developed for the needs of the project GRE-Taste (http://gre-taste.ceti.gr/index.php# (accessed on 10 April 2021)). Metadata about the shop location and the date when the menu was documented were recorded. Care was taken to preserve both the content and the structure of these texts; in the menus, a dish very often belongs to a category of dishes, it has a specific name, and it may be accompanied by an additional description explaining its composition and how it was cooked. A field for notes was introduced for other information on the menu. Orthographical and punctuation particularities were preserved. Figure 1 shows the encoding of the metadata for each menu. Figure 2 shows the entries for two dishes, both salads, that were listed in the menu under the same dish category called “Fresh salads”; each entry contains the name of the dish and a description of it.

Figure 1.

The web database. The administrator’s page and the interface for menu encoding. Slots from top to bottom: type of text, the restaurant or taverna from which the menu was obtained, geographical area, way of encoding in the database (manual or harvesting the web).

Figure 2.

The entries for two dishes in the category “Salads”. Slots from top to bottom: category, name, description, concept. The place of the dish in the facet <Food-dishes> of AΜAΛΘΕΙA is shown in the slot Έννοια “concept” below the entry.

AΜAΛΘΕΙA is an application ontology [7] drawing on the above-described corpus. It has applications in gastronomic tourism, providing multilingual information about the ingredients and the ways of preparation of the dish, in addition to nutritional and cultural aspects. AMAΛΘΕΙA supports interoperability with an internationally established domain thesaurus (Langual).

The ontology development procedure followed relevant best practice recommendations [7]. We retrieved most of the terms from the menu corpus and enriched them with native speaker knowledge, as well as knowledge from recipes, established cookbooks, and scientific literature.

We opted to build AΜAΛΘΕΙA on an exhaustive analysis of the approximately 2500 dish names in the 112 menus we studied; we studied this raw material from a semantic and a syntactic perspective [6]. This analysis allowed for a better understanding of the entities and the relations denoted by the components of dish names. The authors of [8] The semantic and syntactic analysis of named entities in five European languages including Modern Greek presented in [8] is close to our approach from a methodological point of view.

These said, it should be mentioned that dish names in menus have been discussed from historical, sociological, and economic perspectives; for Greek menus, see [9,10]. Historical information is often hidden in dish names [5]. Literature on menu design discusses dish or menu name creation or selection. For example, the authors of [11] provide instructions on how to cope with issues such as word length and provenance, accuracy, and ethnic and foreign words. These aspects of dish naming have not been modeled in AMAΛΘΕΙA, although we occasionally provide this type of information if we consider it useful.

The analysis of dish names has shown them to be noun phrases (NPs) headed by nouns denoting elements of a closed set of entities [6]. The NPs may also include a range of modifiers of the head noun that tend to pick their denotation from the same set, although entities beyond this set are not excluded. We call the entities denoted by the components of the dish names in our menu collection Menu Entities (MEs) and list them below. It should be noted that in about 70% of the dish names in our corpus, MI, Process of preparation, and Ways of preparation are either denoted by the head noun or denoted/entailed by the modifiers.

- Main ingredient. MI is an edible material that characterizes a dish (often in terms of quantity), for instance, “fried cod”, “chicken with okra” where the MI is “cod” and “chicken” respectively;

- Way of preparation, such as “stifado” (meat or vegetables stewed with olive oil, tomato, onions, garlic and bay leaves), or “puréed”;

- Process of preparation, such as “frying” or “grinding”;

- Cuts (of meats and poultry), such as “fillet” or “leg”;

- Place (specific geographical origins of an ingredient, mainly of the MI or of the dish), such as “Thrace” in “feta cheese from Thrace”;

- State of MI, such as “fresh” or “minced”;

- Ingredients of a dish (edible materials included in the dish other than the MI), such as “cream, mushrooms” in “chicken fillet with cream and mushrooms”.

Now, we turn to AΜAΛΘΕΙA and present the entities and the relations we have defined. We justify our choices with facts retrieved from the semantic and syntactic analysis of dish names in [6], the classifications of dishes found in the menus, and other aspects of the Greek gastronomic reality.

3. Results

3.1. The Facets and the Relations

AΜAΛΘΕΙA includes the facets and subfacets shown in Table 1 in Greek alphabetical order. All foods are subsumed by <Foods> and are specified for properties with <Foods> as their domain and the other facets as their range. The following notation is used: <X> if X is a facet or a subfacet, E:X if X is an entity, R:X if X is a relation.

Table 1.

The facets and subfacets of the ontology AΜAΛΘΕΙA.

We proceed to discuss the reasons that have motivated the definition of these facets and properties and the problems stemming from their implementation. Presentation follows a logical order rather than an alphabetical one.

3.1.1. <Functions>

Motivation for <Functions>:

- Dishes have different functions in a meal, such as appetizers or main course dishes. Spear, Ceusters, and Smith [12] (p.106), in their discussion of introducing functions in the BFO ontology, note: “We take it to be characteristic of what it is to have a function that for an object to have a function does not imply that it is realizing this function at every moment in which it exists, or indeed at any moment…the function of a thing is, approximately, what it is supposed to do. This typically involves both what is popularly called a goal or end of some sort and a way of achieving that end.” As an example of the above in the dish/food domain, there are several dishes that are listed as appetizers in the menus but can be consumed as main course dishes as well;

- Functions are signaled in Greek gastronomy with the time sequence in which dishes are served. A typical sequence is E:ορεκτικό “appetizer” followed by E:κυρίως πιάτο “main course“ followed by E:επιδόρπιο “dessert”. They are also signaled by the occasion; for instance, along with an ouzo, one would have a meze rather than a main course dish or an appetizer;

- Consumers want to know the function of a food for financial or health reasons; for instance, one might prefer to have only a main course dish because typically, main course dishes come in larger portions than appetizers or mezedes, while desserts are not normally considered enough to support a meal;

- Restaurants very often classify dishes by function and sometimes require that clients have dishes from at least two of them. Ιn our corpus, the classifications “appetizer” and “dessert” are encountered frequently, but the classification “main course” seems to be the default choice.

To model the above, we introduce the facet <Functions> and define a relation R:Λειτουργία στο γεύμα “Function in the meal” from <Foods-dishes> to <Functions> (see also Section 3.1.2). The facet comprises the following entities: E:επιδόρπιο “dessert”, E:κύριο πιάτο “main course”, E:μεζές “meze”, E:ορεκτικό “appetizer”, E:παιδικό μενού “children’s menu”, E:σαλάτα “salad”, and E:συνοδευτικό “side dish”.

3.1.2. <Food-Dishes> and <Food-Ingredients>

Motivation for <Food-dishes> and <Food-ingredients>:

- In a restaurant, the transaction is organized around dishes, but in a grocer’s shop, transactions are organized mainly around ingredients. Consequently, different social infrastructure is required for the circulation of these two types of food;

- Menus list names of dishes. Some of them provide a description of the dishes in terms of their ingredients and other properties;

- Recipes are about dishes: they all explain how dishes are created out of ingredients that are listed separately.

In AΜAΛΘΕΙA, a food-dish (or simply a dish) is classified as any food that has a function in the meal. Functions in the meal have been discussed in Section 3.1.1. The subfacets of the facet τροφή “<Foods>”, namely <τροφές-πιάτα> “<Food-dishes>” for which functions in the meal are foreseen and <τροφές-συστατικά> “<Food-ingredients>”, for which no such functions are foreseen, have been designed to represent this division. We use the relation R:Λειτουργία στο γεύμα “Function in the meal” that differentiates <Food-dishes> from <Food-ingredients>. The relation has the facet <Functions> as its range, and it is defined only for the entities subsuming <Food-dishes> and not for the entities subsuming <Food-ingredients>. R:Function in a meal characterizes a food as a dish, and all foods with a function in a meal are dishes. R:Function is an essential property [13] because a dish always has a function in a meal but an ingredient never does (unless a function is assigned to it, e.g., “side dish”, but then it is served as such), and it is rigid [13,14] because it characterizes all the instances of the particular dish, i.e., it cannot be the case that an instance of a particular dish is not considered an independent dish with a certain function in the meal. R:Function may take more than one value for the same dish; for instance, French fries may be characterized in different menus as an appetizer, a main course or a side dish.

<Food-ingredient> stands for raw materials used for cooking a dish as well as for complex “constituents” that require separate preparation; béchamel sauce or Bolognese sauce are typical examples of complex constituents of a dish. However, sauces do not have a function in the meal: they are either mixed with the other ingredients of the dish during cooking or they are served as an optional condiment of the dish (and not as a side dish).

Furthermore, it should be noted that in the menus, a dish that can be consumed on its own as a main course, e.g., pilaf, may appear in the name of another dish, e.g., μοσχάρι με πιλάφι “beef with pilaf” and κοτόπουλο πιλάφι “chicken pilaf”. These dish names may be ambiguous. They might mean that pilaf is cooked separately and is served as a side dish; in this case, menus often provide alternatives such as “beef with pilaf or French fries or steamed vegetables”. Alternatively, they might mean that the rice is cooked together with the meat/chicken. In the first case, pilaf is a dish with more than one function in the meal, and in the second case, the respective dishes have rice as an ingredient, while their name contains the noun “pilaf”.

Both <Food-dishes> and <Food-ingredients> are structured hierarchically with the is_a relation. In <Food-dishes>, the question is whether dish Y has X as its main ingredient, and if yes, dish Y will belong to the class E:X (dishes). The class comprising the dishes that have X as their main ingredient is assigned the name X (dishes), where X is the main ingredient, if there is no special Greek term designating it. In <Food-ingredients>, the question is whether ingredient X is a subspecies of ingredient Y—for instance, φέτα “feta” is a kind of τυρί “cheese”; if the answer is “yes”, then X is_a Y—for instance, E:feta is_a E:cheese.

Since the MI has a prominent role in AΜAΛΘΕΙA, we offer some further motivation for its definition:

- The analysis of the semantics and the structure of dish names presented in [6] establishes the MI as their most important component. Ιf the dish name is not idiosyncratic, the MI is most often stated explicitly, and if it is not, it should be easily entailed from the context;

- Consumers often express needs of the type “today I would like to have meat/fish/spaghetti/vegetables”: they mean that they fancy a dish characterized, often in terms of quantity, by the named ingredient;

- Menus most often define dish categories by the name of the main ingredient, such as E:κρεατικά “meats”;

- Restaurants may specialize in dishes with a specific main ingredient, such as fish, seafood, or meats.

It is for these reasons that we define the essential property [13] R:Κύριο συστατικό “main ingredient“ (R:MI) that differentiates a daughter entity of <Food-dishes> from all its other siblings. R:MI allows for the definition of classes of dishes by their MI in a way that all dishes with λαχανικά “vegetables” as their MI belong to the class E:λαχανικά (πιάτα) “vegetables (dishes)” and to no other class, while dishes with other MIs do not belong to the class E:λαχανικά (πιάτα) “vegetables (dishes)”. In other words, if E:X is the mother of E:D, where X and D are foods, and if both E:X (dishes) and E:D (dishes) are defined, then E:X (dishes) will be the mother of E:D (dishes), and the value of R:MI defined for E:X(dishes) will be E:X and for E:D(dishes) will be E:D. We use Figure 3 to depict this structure and use the arrows to indicate (some of) the correspondences between entities of the <Food-dishes> and the <Food-ingredients> subfacets: it is precisely this type of correspondence that is modeled with the R:MI.

Figure 3.

Some of the correspondences between cheese (dishes) and cheese (ingredient).

The study reported in [6] revealed cases with two equally plausible MI candidates, most demonstrably the spaghetti and risotto dishes; this is the situation when the nouns μακαρόνια/μακαρονάδα “spaghetti” and ριζότο “risotto” head the NP or the compound denoting the dish, i.e., they head the dish name. Such is the dish name μακαρόνια με κιμά, Lit. spaghetti with minced meat, “spaghetti Bolognese” that is headed by μακαρόνια. The name of this dish may be found in the menus under κιμάδες “dishes based on minced meat” or under ζυμαρικά “pasta”. In order to represent the fact that spaghetti Bolognese is listed on restaurant menus either as a minced meat dish or as a pasta one, we introduce multiple inheritance with the relation R:Επιπλέον ευρύτερη έννοια “Additional broader concept” (R:ABC) that receives more than one value. R:ABC is an is_a relation; therefore, μακαρόνια με κιμά “spaghetti Bolognese” ends up with two MIs. Figure 4 shows that spaghetti Bolognese has two MIs. MIs are signaled with blue dots; in Figure 4, there are four blue dots because the immediate parents of the two MIs are also listed.

Figure 4.

“spaghetti Bolognese”: example of dish with two main ingredients (MIs): spaghetti and minced meat.

3.1.3. <Ways of Preparation> and <Processes of Preparation>

The chemical, thermal, or mechanical process used to prepare a dish features prominently in cooking vocabularies, including dish names. Reference [15] offers a contrastive analysis of English, French, German, Mandarin Chinese, Japanese, Yoruba, Navajo, and Amharic cooking vocabularies drawing mainly on terms denoting thermal processes used in cooking, such as boiling and smoking; the author claims that thermal, chemical, and mechanical processes are relatively common across ethnic cuisines and allow for building relevant taxonomies.

Our study of the menus showed the importance of another aspect of cooking, that of distinctive families of dishes, for instance, the family of stifado dishes in the case of Greek cuisine. These families of dishes, which are partially responsible for the ethnic/local character of a cuisine, share some ingredients, the overall shape and texture of the food, and the process of preparation; we classify these as ways of preparation.

The diagnostic we have used to differentiate between individual dishes and ways of preparation is whether in the menus we find different dish names containing the term which denotes the way of preparation combined with different MIs that span several food categories and/or several ways of thermal processing. For instance, stifado occurs with veal, rabbit, wild boar, cuttlefish, and cauliflower as an MI and definitely fulfils the “many MIs” diagnostic. Another example is schnitzel that may be made of pork, veal, chicken, or mushrooms and may be fried or roasted; on the web, we find declarations such as “hallmarks of schnitzel include very thin meat and a thin crisp coating” (https://www.thekitchn.com/whats-the-difference-between-schnitzel-and-wiener-schnitzel-236436 (accessed on 15 January 2021)) that put restrictions on the shape and the texture of the dish but not on its thermal processing. Stifado and schnitzel contrast with dishes such as ιμάμ μπαϊλντί “baked eggplant stuffed with onions and garlic in a tomato sauce”. These dishes present no variations as regards the MI (eggplant) and moussaka that is always cooked in the oven (invariable final thermal processing).

Motivation for <Processes of preparation>:

- Dish names transparent as regards both the MI and the process of preparation are common, for instance, τυριά σχάρας “grilled cheese”;

- Traditionally, Greek restaurants may specialize in a certain process of preparation, in particular in grilling or in μαγειρευτά “cooked with some sauce in a pot placed on the source of the heat”, and a ψησταριά “grilling house” is a very common type of specialized restaurant anywhere in Greece;

- The menus often classify dish categories by the process of preparation, e.g., σχάρας “grilled”, μαγειρευτά;

- The process of preparation has effects on the dietary properties of a dish, for instance, people who try to lose weight would prefer a steak roasted on charcoal rather than a piece of meat cooked in some olive-oil -rich sauce;

- The process of preparation may have social dimensions. For instance, in many places in Greece, Easter is celebrated with roasting a suckling lamb or a kid goat on the spit. Of course, the same meat can be cooked in a pot on the stove and is cooked in this way in certain areas of the country, but the spit-process is the hallmark of a special social occasion with related customs.

Motivation for <Ways of preparation>:

- Dish names often include components that denote the dish family, such as “stifado” as in κουνέλι/λαγός/μοσχαράκι στιφάδο “rabbit/hare/veal stifado”, or the shape or texture of food, such as “pie” or “purée”;

- Consumers may ask for dishes of a particular family, such as “stifado”;

- The menus often classify dish categories by the way of preparation, such as λαδερά, Lit. in olive oil, “vegetable dishes cooked with lots of olive oil”. Λαδερά “in olive oil” is a family of Greek vegetable dishes that essentially require cooking with (large quantities of) olive oil. This category may comprise dishes with fixed names that do not indicate a main ingredient, such as μπριάμ “a mixture of vegetables such as zucchini, eggplant, okra, etc., cooked with tomato, onion, and lots of olive oil” or dishes with names of the type φασολάκια λαδερά “green beans cooked in olive oil and tomato” that is normally classified by its MI as a daughter of E:vegetables (dishes);

- Dish families may be related to social occasions. For instance, in Orthodox Greece, μαγειρίτσα (magiritsa) “thick soup made of the suckling lamb’s or the kid goat’s entrails and intestines, lettuce, spring onions, and herbs such as dill and fennel, dressed with lemon-and-egg sauce” is the ceremonial dish of the Holy Saturday night when Christ is resurrected.

- To represent these facts, AΜAΛΘΕΙA provides two facets:

- ○

- <Διεργασίες παρασκευής> “<Processes of preparation>” with two subfacets:

- ○

- <Θερμική ή Χημική κατεργασία> “<Τhermal or Chemical processing>” with daughter entities such as βρασμός “boiling”, τηγάνισμα “frying”, etc.;

- ○

- <Mηχανική κατεργασία> “<Mechanical processing>” with daughter entities such as άλεση “grinding”, etc.

- <Τρόποι παρασκευής> “<Ways of preparation>” with two subfacets:

- ○

- <Σχήμα–υφή–μορφή> “<Shape–texture–form>” and daughter entities such as E:γεμιστό “stuffed”, Ε:κεφτές “ball”, Ε:πίτα “pie”, etc.;

- ○

- <Με χαρακτηριστικά συστατικά> “<With distinctive ingredients>” with daughter entities such as Ε:στιφάδο “stifado”, Ε:λαδερά “in olive oil”, Ε:κοκκινιστός “with tomato sauce”, etc.

The split of the facet <Ways of preparation> to two subfacets, by shape–texture–form and by distinctive ingredients, reflects the semantics of dish names. The distinctive ingredients do not include the MI because the definition of families of dishes, which these two subclasses represent, requires that the family shares other features than the MI. For instance, the stifado family shares the use of shallots, bay leaves, tomatoes, and olive oil.

The facets are hierarchically structured with the is_a relation. Sometimes, in particular in the case of the <Shape–texture–form> subfacet, subsumption is defined on the basis of native speaker judgment. For instance, E:πίτα “pie” stands for a type of food characteristic of Greek gastronomy. Πίτα “pie” is either a dish where some (semisolid) mass, the “filling”, is wrapped/rolled in some type of pastry and is baked or fried, or a dish consisting of a baked or fried flat mass (a so-called ανοιχτή/ξεσκέπαστη πίτα “open/uncovered pie”). Given this variation in shaping/forming the filling and in thermal processing, the entity E:pie has several daughter entities all conceived by the native speakers of Greek as “types of pie”, for example, ανοιχτή/ξεσκέπαστη πίτα “open/uncovered pie”, μπουρέκι/μπουρεκάκι “rolled pie/little rolled pie”, etc.

As already mentioned, the facet <Ways of preparation> accommodates what we have called families of dishes. This is a distinctive feature of AΜAΛΘΕΙA. There are several dish names that contain a constituent denoting a way of preparation (for an extensive discussion on the syntactic and semantic properties of these names, please refer to [6]). We observe that these names reflect a tendency of “upgrading” classical dishes to families of dishes. This “upgrading” demonstrates the phenomena of dish variation and recipe evolution [1,2]. Some examples follow:

- In the menus, we find a wealth of dishes whose names have stifado as a component, e.g., beef/rabbit/cuttle-fish/cauliflower; stifado: a variety of MIs can be cooked in the stifado way (that seems to have hare as an MI originally);

- It has already been said that throughout Orthodox Greece, μαγειρίτσα (magiritsa) is an outstanding dish consumed after the Holly Saturday midnight when Resurrection is announced. Magiritsa is typically cooked with the entrails of the suckling lamb or the kid goat that will be roasted on the spit next morning (the Easter day). This profoundly ceremonial dish has recently acquired a vegetarian namesake cooked with mushrooms as its MI. This new dish is called “vegetarian magiritsa (with mushrooms)”, although a description of the sort “mushroom soup with lettuce, spring onions, and a tahini-and-lemon sauce” could suffice, being closer to the facts (for instance, tahini-and-lemon sauce is never used for magiritsa).

Dish variation and recipe evolution reveal social and historical tendencies. One such prominent example is Chef N. Tselementes’ replacement of the traditional γιαουρτόκομμα “sauce made of yogurt and egg” with the béchamel sauce in emblematic dishes such as the μουσακάς “moussaka” [16]. This took place in the 2nd–6th decade of the 20th century (https://www.kathimerini.gr/863220/article/gastronomos/syntages/smyrnaiikos-moysakas (accessed 15 January 2021)) when Greek society opened to Western cooking. The “vegetarian version of magiritsa” also indicates contemporary social tendencies.

Variations, such as in the magiritsa case, create a conflict between (a potential) classification by dish name and by the MI. A classification by dish name would not be of little use since the way of preparation is a crucial piece of information about a dish. In our approach, although both μοσχαράκι στιφάδο “stifado with veal” and κουνουπίδι στιφάδο “stifado with cauliflower” have stifado in their names, they will be classified in different categories in the <Food-dishes> subfacet because their main ingredients are different, namely beef and cauliflower, respectively.

To allow AΜAΛΘΕΙA to relate food entities with way of preparation ones, we defined a set of relations from <Foods> to <Ways of preparation> and to <Processes of preparation> as follows:

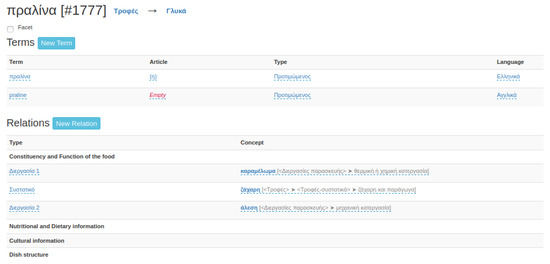

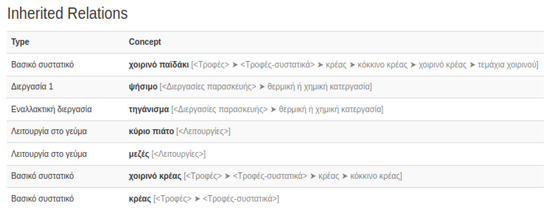

Two relations R:Τρόπος κατεργασίας 1, 2 “Way of processing 1, 2” relate a food entity to the process used for its preparation. R:Way of processing 1, 2 has <Foods> as its domain and <Process of preparation> as its range. Indices 1 and 2 allow for encoding the temporal order of applying different processes in order to create a particular dish or ingredient. For instance, Figure 5 shows the encoding of πραλίνα “praline” that requires two processes in the following order: καραμέλωμα “caramelization” and άλεση “grinding”, of which the first is a thermal process and the second a mechanical one (not a thermal or chemical one).

Figure 5.

πραλίνα “praline” first undergoes the thermal process (Διεργασία) of καραμέλωμα “caramelization” and then the mechanical process of άλεση “grinding”.

While temporal order of ways of processing can be encoded, AΜAΛΘΕΙA should be further developed to express precisely which ingredients undergo which process. This is only partially possible at the moment, for instance, if the dish is the combination of more than one separate dish (such as μπακαλιάρος σκορδαλιά “cod with garlic dip” discussed in Section 3.3) or contains a sauce as an ingredient; providing AMAΛΘΕΙA with this expressive ability is one of our immediate plans.

In restaurant menus, the same dish may be offered cooked in different ways. We have defined R:Εναλλακτική διεργασία “alternative processing” that maps entities in <Foods> on entities in <Process of preparation>. An example is given in Figure 6: E:χοιρινά παϊδάκια “pork ribs” may be served roasted (process ψήσιμο) or fried (process τηγάνισμα).

Figure 6.

R:Εναλλακτική διεργασία “alternative processing” is used to encode the second possible (thermal) process of preparation that may be applied on pork ribs.

If the dish/ingredient is characterized by its shape (or texture or form), as in the case of the schnitzel family of dishes (Section 3.1.3), or some characteristic ingredients, as in the case of the stifado family of dishes, the relation R:Τρόπος παρασκευής “Way of preparation” is used to map entities in <Foods> to entities in <ways of preparation>. We have also defined the relation R:Εναλλακτικός τρόπος παρασκευής “Alternative way of preparation”. Figure 7 shows the case of E:κολοκυθόπιτα “zucchini pie”. The light blue dots mark the relations R:Way of preparation and R:Alternative way of preparation.

Figure 7.

Τhe dish κολοκυθόπιτα “zucchini pie” may have the form of an open pie “ανοιχτή πίτα”, or the alternative form of a covered pie “σκεπαστή πίτα”, i.e., covered with some type of pastry.

One last point regarding the relations between <Foods> and <Ways of preparation> that have been modeled as is_a relations on the one hand and <Processes of preparation> on the other that have not been modeled as is_a relations is that the facet <Processes of preparation> models occurrents, i.e., entities that occur or happen, while <Foods> models continuants, i.e., entities that continue or persist through time [7] (p. 87); therefore, no is_a relation can be defined between them. The facet <Ways of preparation> models types of dishes. The relations R:Way of preparation and R:Alternative way of preparation are is_a relations because a dish that has the features of a soup is of type “soup”.

3.1.4. <Τόποι προέλευσης> “<Place of Origin>”

Μοtivation for the facet <Place of origin>:

- The origins of a dish or an ingredient can be of interest to the consumers because they are often considered a guarantee of quality or for other reasons, such as cultural ones;

- Places of origins may be encountered as modifiers of the dish name head, e.g., φέτα Θράκης “feta from Thrace”.

However, highlighting the origin of a food in a menu may be considered [17] (p.130) an overused technique that “identifies the source of the ingredients instead of emphasizing the way of preparation” in order to cause “an aura of excitement in a conventional form”.

The facet <Τόποι προέλευσης> “<Place of origin>” is structured with the part–whole relation. A relation R:Καταγωγή τροφής “Food’s origins” is defined with <Foods> as its domain and <place of origin> as its range.

3.1.5. <Kατάσταση τροφής> “<State of Food>”

This facet models the condition of the food such as Ε:κατεψυγμένος “frozen”, Ε:νωπός (φρέσκος) “fresh”, and ways of carving up foods such as Ε:κιμάς “minced meat”, Ε:κυδωνάτος “sliced tomato or potato in four large pieces”, Ε:στικς (μπαστουνάκια) “sticks”, and Ε:φέτα “slice”. These terms feature in menus as modifiers of dish name heads. A relation R:Κατάσταση πιάτου “Dish condition” has <Foods> as its domain and <State of food> as its range.

3.1.6. <Πηγές τροφίμων> “<Food Sources>”

The source of an ingredient may be an (edible) entity such as an animal, e.g., “suckling lamb” or a plant, e.g., “olive tree”; they are never encountered in dish names. We assume that the phemomenon of synecdoche applies in these cases: if the word “lamb” appears in the name of a dish, we consider it denoting the meat of this animal rather than the animal itself. The facet <Πηγές τροφίμων> “<Food sources>” is structured with the is_a relation over animal and plant species and is almost fully aligned with the Langual thesaurus. The relation R:Πηγή “Source” has <Food-ingredients> as its domain and <Food sources> as its range. <Part of source> is a subfacet of <Food sources> that models parts of animals and plants. We do not elaborate more on this facet that follows Langual closely.

3.1.7. <Koπές> “<Cuts>”

Meat and poultry cutting has been a conceptually and linguistically unruly field throughout its very long history. Reference [18] provides a good picture of the problem by listing examples of differences among cuts in the USA and in Europe together with social, historical, or other comments on the linguistic evolution of the field. The vagueness that characterizes the field is acknowledged in FoodOn (Comment on the entity cut of meat in FoodOn ontology: http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/FOODON_03530146 (accessed on 30 January 2021)).

The situation is no better as regards the cuts used in Greek cuisine. However, there was strong motivation for taking up the exercise in AΜAΛΘΕΙA:

- Consumers may be particular as to which part of an animal they prefer; for instance, someone may not prefer a dish based on a cut of meat with excess fat;

- Dish names may contain a component denoting the cut, particularly in restaurants specialized in meat dishes;

- The impact of cutting on the taste and the value of a dish is underlined in a detailed relevant FAO report (Comment on the entity cut of meat in FoodOn ontology: http://purl.obolibrary.org/obo/FOODON_03530146 (accessed on 30 January 2021)):“Within each animal carcasses and associated with the different muscles there are variations in tenderness that dictate how different cuts of meat should be prepared to yield the most palatable foods. Because of these differences in tenderness, juiciness and flavour, each meat cut should be merchandized according to its availability and palatability characteristics. Consequently, different prices should be charged for different cuts from the various meat animals so that consumers have choices. […] In order to get the maximum eating satisfaction and also the maximum nutritional value, each cut must be matched with the correct cooking procedure. Loin cuts which are generally tender should be prepared by broiling or other dry-heat methods while cuts with considerable bone and connective tissue from the shanks should be either braised or simmered for stews and soups.”

The <Cuts> facet of AΜAΛΘΕΙA, which was structured with the is_a relation, was developed by taking into account the Greek and European legislation, Langual, and the input of the partners of the project GRE-Taste (http://gre-taste.athenarc.gr/newindex.php, accessed on 13 April 2021) in the framework of which AΜAΛΘΕΙA was developed. The encoded cuts are assumed to apply to all the animal groups, which is a choice dictated by the need of a good alignment of AΜAΛΘΕΙA with Langual (Langual does not make this distinction) and by the fact that there is not enough Greek documentation to support a distinction of cuts based on the animal. An attempt was made to match the Greek cuts mainly with the American and, secondly, with the French ones that are documented in Langual. For example, the diminutives χεράκι “little hand”, κεφαλάκι “little head”, and ποδαράκι “little leg” are used in Greece and either relate to specific animals (a little head is the head of a suckling lamb or a kid goat) or to a specific way of preparation; for instance, little legs are used for the soup πατσάς “tripe soup”. These special Greek cuts were considered daughters of cuts such as “hand” and “head” that are further specified by the animal species to which they are applied. Overall, there is a strong need for a unified documentation of Greek cuts; at the same time, the two cuts’ paradigms that are documented in Langual (American and French) should be harmonized.

In AMAΛΘΕΙA, cuts are entities modeling the anatomical and geometric characteristics of the pieces of the carcass. The relation R:Koπή “Cut” has <Food_ingredients> as its domain and <Cuts> as its range, and the relation R:Mέρος πηγής “Source part” has <Cuts> as its domain and <part of source> as its range.

3.2. More on the Encoding of Dish Variation

AΜAΛΘΕΙA differs from other food ontologies in that it pays extra attention to dish variation. This necessity emerged from the modeled domain, namely the contents of restaurant and pastry shop menus. Modeling of dish variation is achieved with a set of entities and relations, some of which have been discussed in the preceding sections, while the remaining ones are discussed below.

AΜAΛΘΕΙA employs the relations shown in Table 2. The section is concluded with a presentation of AMAΛΘΕΙA’s overall approach to encoding dish variation.

Table 2.

Relations.

3.2.1. Necessary, Alternative, and Optional Ingredients

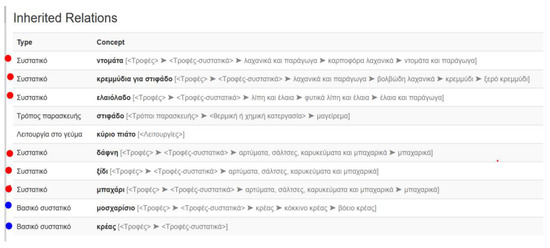

Although they do not qualify as MIs, some ingredients cannot be omitted from a dish; for instance, onion and garlic are the compulsory ingredients for a plethora of Greek dishes with MIs such as meat or vegetables. We reserve the name “ingredient” for this type of ingredients and define a relation R:Συστατικό “Ingredient“ with <Foods> as a domain and {<Foods>,<Beverages>} as a range. R:Ingredient is used to assign ingredients to dishes. R:Ingredient may receive multiple values for a given dish. Figure 8 shows the entry of μοσχάρι στιφάδο “beef stifado” where the R:Συστατικό “Ingredient“ receives six values (marked with the red dots), namely tomatoes, shallots, olive oil, bay leaves, vinegar, and allspice. The blue dots mark the MI, which is E:beef and its immediate parent E:meat in the <Food-ingredients> hierarchy.

Figure 8.

The MI and the other ingredients in the documentation of the dish μοσχάρι στιφάδο “beef stifado”.

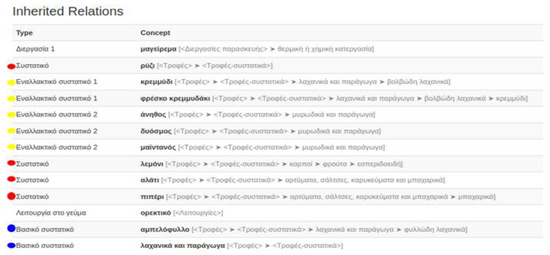

Sometimes, a dish requires a type of ingredient, such as a type of onion or herbs, and several ingredients of this type may be used with no effect on the dish’s identity. For instance, μαγειρίτσα “magiritsa” is cooked with herbs. In Crete, μάραθος “fennel” is used for this dish, while in the mainland, mostly άνηθος “dill” is preferred, but occasionally, both herbs may be used. We call this type of ingredient alternative ingredient. The same dish may have more than one alternative ingredient; for instance, ντολμαδάκια γιαλαντζί “dolmadakia gialantzi” (stuffed vine leaves with rice and herbs only, no minced meat) may be cooked with onions or green onions or both (first alternative ingredient) and with parsley, dill or mint or some combination thereof (second alternative ingredient). We have defined three relations, namely R:Εναλλακτικό συστατικό 1,2,3 “Alternative ingredient 1,2,3” (with <Foods> as both a domain and a range), in order to accommodate dishes with several ingredients of this type. Figure 9 shows the dolmadakia gialantzi entry: R:Alternative ingredient 2 takes the values E:dill, E:parsley, and E:mint, and R:Alternative ingredient 1 takes the values E:onion and E:green onion (as explained above). The yellow dots mark alternative ingredients, red dots mark ingredients, and the blue dots the MI and its immediate parent in the <Food-ingredients> hierarchy.

Figure 9.

MI, ingredients, and alternative ingredients for ντολμαδάκια γιαλαντζί “dolmadakia gialantzi”.

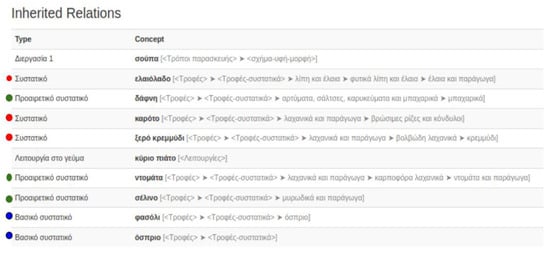

Finally, it may be the case that optionality of an ingredient does not affect a dish’s identity, for instance, φασολάδα “bean soup” may be cooked with or without tomato. We define a third type of relation, namely R:Προαιρετικό συστατικό “Optional ingredient” (with <Foods> as both a domain and a range) to accommodate this type of ingredient. Figure 10 shows the φασολάδα “bean soup” entry, where the relation R:Optional ingredient (marked with green dots) takes three values, namely E:δάφνη “bay leaves”, E:ντομάτα “tomato”, and E:σέλινο “celery”. As before, red dots mark ingredients and blue dots the MI and its immediate parent in the <Food-ingredients> hierarchy.

Figure 10.

MI, ingredients, and optional ingredients of the dish φασολάδα “bean soup”.

3.2.2. Encoding Dish Variation

We have identified the following types of dish variation:

- Some ingredients are optional and cannot be substituted; for instance, one may use or may not use onion in lemonato, but onion cannot be substituted with any other ingredient;

- Alternative ingredients. There are groups of similar ingredients that should be present in a dish, either some of them or all of them. For instance, magiritsa is cooked with either suckling lamb or kid goat entrails or both. Either of these meats or both may be used for the dish without affecting its identity at all. However, the presence of meat is compulsory in order to establish the identity of the dish, or at least it was until recently, as explained below;

- Type of dish. Sometimes, the name of an identifiable dish is used as the name of a family of dishes which are thought to share some essential features that set them apart from any other dish or family of dishes. Greek cooking includes several names of families of dishes (lemonato, kokkinisto, stifado, frikase, avgolemono, etc.); we have chosen magiritsa as a working example because it is only recently that it has become the name of a family of dishes. Thus, while magiritsa is a celebrated ceremonial dish that contains the entrails of a suckling lamb or kid goat or both, them being its most distinctive feature, recent trends have introduced vegetarian magiritsa in which meat is replaced with mushrooms and vegan magiritsa in which egg-and-lemon sauce (another distinctive feature of the dish) is replaced with tahini-and-lemon sauce. One could certainly argue that what is introduced as vegan magiritsa is just a type of mushroom soup that could be called by any name and that the name magiritsa was selected because it is so established and, also, because it allows vegan people to participate to what is perhaps the most celebrated family meal in the Greek Orthodox tradition. We append here a translation of a justification of the name magiritsa from a recipe site that proposes the vegan version of the dish: “Μagiritsa, the humble, the festive, is and will forever be the ultimate gastronomic experience of Greek cuisine. But you see, what makes me eat it after midnight each time in a bliss are not the livers or the intestines or the other entrails. The essence of magiritsa are the herbs -the dill, the fennel, the chervil, the lettuce and whatever other herb ladies use- and its fragrant, thick texture…” (https://www.madameginger.com/syntages/syntages-mageirikis/kyrios-piata/mageiritsa-me-manitaria-vegetarian-kai-pentanostimi/ (accessed on 15 January 2021)). In short, the author of the recipe has identified the features shared by a family of dishes, here the family of the magiritsa dishes.

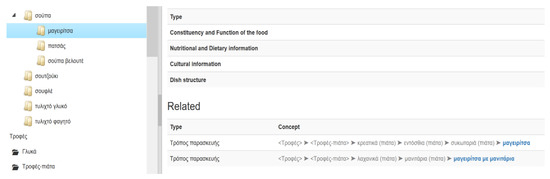

We have captured the idea of dish family by introducing the facet <Ways of preparation>. In Figure 11, on the left part of the attached screenshot from AΜAΛΘΕΙA, the entry for the dish family E:μαγειρίτσα “magiritsa” is shown as a daughter of E:σούπα “soup” (which, in turn, is one of the daughters of E: shape–texture–form). On the right part of the screen, magiritsa (way of preparation) is related with magiritsa (dish) and magiritsa with mushrooms (dish) with R:Τρόπος παρασκευής “Way of preparation”.

Figure 11.

The type of dish E:magiritsa. All magiritsa dishes are related to it with R:Way of preparation.

3.3. <Dish Structure>

The arrangement of the different ingredients of a dish may be essential for its identity. We have identified the following cases and provided the encoding means explained below:

- Ingredients are placed in layers

Ingredients are arranged in layers in most spaghetti-with-sauce dishes. Moussakas, a celebrated dish of Greek cuisine, also consists of three parts, namely fried eggplant/zucchini which can be served as an independent dish, separately cooked minced meat, and béchamel. These three parts are placed on top of each other in the order vegetables–meat–béchamel, and the whole structure is baked. To this end, we have defined three relations, R:Στρώση 0,1,2 “Layer 0,1,2” with values in the <Foods> facet.

- Ingredients are placed one next to the other, even in different pots

Such is the case of μπακαλιάρος σκορδαλιά “fried cod with garlic dip”. This situation is documented with the relation R:Παρατιθέμενο συστατικό-πιάτο “Side dish-ingredient” with values in the <Food-dishes> facet.

- Ingredients are mixed

Most dishes belong to this category, even certain spaghetti-with-sauce dishes such as carbonara. This is considered the default situation and is not documented explicitly.

3.4. Implementing AΜAΛΘΕΙA

AΜAΛΘΕΙA is a proprietary project; no ready-made tools were used. It exists as an SQL structure. The application is a web application that runs on a web server. We store the data in a relational database (MySQL).

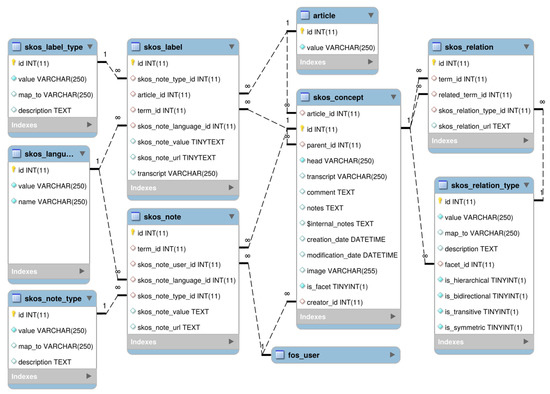

AMAΛΘΕΙA is SKOS (https://www.w3.org/TR/skos-reference/ (accessed 30 March 2021)) compatible (we plan an OWL (https://www.w3.org/OWL/ (accessed on 30 March 2021) implementation in the near future). The primary entity of the database is the “skos_concept” that represents an AΜAΛΘΕΙA entity. Each AΜAΛΘΕΙA entity can have a parent AΜAΛΘΕΙA entity—therefore, a tree may be created—and can also be marked as a facet. An AΜAΛΘΕΙA entity also includes:

- one or more lexical labels (database entity “skos_label”);

- relations with other AΜAΛΘΕΙA entities (database entity “skos_relation”);

- notes (database entity “skos_note”).

The entity “skos_label” contains a lexical form (a string of UNICODE characters), a language tag, and a type. The entity “skos_relation” contains a pointer to the related AΜAΛΘΕΙA entity and a type. The entity “skos_note” contains the documentation properties of the AΜAΛΘΕΙA entity. It contains a free text field, an URL field, a language tag, and a type.

Label, Note, and Relation type values are also database entities (skos_label_type, skos_note_type, skos_relation_type), and their values are not hardcoded. Each type has a “map_to” property that is used to map AΜAΛΘΕΙA types to the types of the SKOS data model.

The skos_relation_type has also the following properties:

- “is_hierarchical”, meaning that the relationship is hierarchical;

- “domain”, the root of the subtree of the AΜAΛΘΕΙA entities that can be used as the domain of this relation type;

- “range”, the root of the subtree of the AΜAΛΘΕΙA entities that can be used as the range of this relation type.

The model of the AΜAΛΘΕΙA database is given in Figure 12. The AΜAΛΘΕΙA content can be downloaded in RDF form from http://gretaste.ilsp.gr/rdf/dictionary.rdf (accessed on 12 April 2021).

Figure 12.

The model of entities and relations in the AΜAΛΘΕΙA database.

3.5. Evaluating AΜAΛΘΕΙA

3.5.1. The Structure of AMAΛΘΕΙA

AΜAΛΘΕΙA draws on 112 menus containing about 2500 dish names, of which about 400 are unique occurrences. All the dish names have been encoded in the ontology. About 80% of the dish names are NPs headed by a noun or a noun multiword expression denoting the MI, the way of preparation, the process of preparation or the cut, and the remaining names are idiosyncratic. AΜAΛΘΕΙA is trilingual (Greek, English, Russian). The upper half of Table 3 describes the current size of AΜAΛΘΕΙA (including the modeling of dietary and cultural information that has not been discussed in this article).

Table 3.

Numbers about AΜAΛΘΕΙA (as of 30 January 2021).

For the evaluation of the structural dimension (the schema) of AΜAΛΘΕΙA [19,20], we consider only the facets of the ontology presented so far, namely the schema of the ontology concerning dishes and their constituency, but not dish instances nor their dietary and cultural aspects (lower half of Table 3). We adopt metrics proposed in [20] that address aspects of the design of the ontology and indicate the richness, width, depth, and inheritance of an ontology schema design.

- Relation Richness (RR)

The RR of a schema is defined as the ratio of the number of non-inheritance relations (PR) divided by the total number of relations defined in the schema, i.e., the sum of the number of inheritance relations (HR) and non-inheritance relations (PR): RR = PR/(PR + HR). RR reflects the diversity of the types of relations in the ontology.

- II.

- Inheritance Richness

The Inheritance Richness (IR) of a schema is defined as the average number of daughter entities CE per mother entities HE: IR = CE/HE. An ontology with a low IR is a deep (or vertical) ontology, which indicates that the ontology covers a specific domain in a detailed manner, while an ontology with a high IR is a shallow (or horizontal) ontology, which indicates that the ontology represents a wide range of general knowledge with a low level of detail.

Table 3 shows that AΜAΛΘΕΙA covers a wide range of knowledge about dishes in enough detail. AΜAΛΘΕΙA is under constant development, and these measures will be further improved.

3.5.2. Completeness

Completeness measures whether the domain of interest is appropriately covered by comparing the ontology against a text corpus (that significantly covers the domain), or with a gold reference ontology, if available [21].

The domain of interest in our case is represented by a corpus of menu entries: with the term “menu entry”, we refer to each distinct dish or drink or other entry in our corpus of menus. For the purposes of evaluation, 48,757 menu entries were accessed through a delivery site and another 2750 through the digitization of restaurant menus that were collected and encoded manually as described in Section 2. The figures in Table 4 should be read with the following in mind:

Table 4.

AΜAΛΘΕΙA’s completeness (as of 30 March 2021).

- Many menu entries are about beverage brands, approximately 30% of an average menu; AΜAΛΘΕΙA does not contain such information (yet);

- Several menus are in English or contain an English translation of their contents;

- Menus may contain free text such as explanations on the prices;

- AΜAΛΘΕΙA was developed drawing on 112 manually collected menus; later, another 30 menus were added to the corpus against which the ontology is evaluated.

AΜAΛΘΕΙA scores within the expected limits with manually collected menus, taking into account the points made above. In fact, restaurants that do not have food delivery as their main practice were the intended target of the ontology. It is interesting that AΜAΛΘΕΙA covers to a much lesser extent the language used in delivery menus; we assume (and it remains to be proved) that this is due to the wider usage of the Latin alphabet in these menus and to the different dishes offered by the two types of dish providers.

3.5.3. Ontology Competency Questions

Application ontologies aim to provide correct answers to specified types of question [22]. Ontology competency questions are often used to evaluate ontologies from the point of view of user satisfaction. The question types shown in Table 5 were specified for the purposes of the project GRE-Taste that has supported the development of AΜAΛΘΕΙA. The ontology aims to support a gastronomy-centered touristic site (http://gre-taste.athenarc.gr/newindex.php (accessed on 11 April 2021)) for East Macedonia and Thrace and a mobile phone application with the same purposes.

Table 5.

Ontology competency questions regarding AΜAΛΘΕΙA.

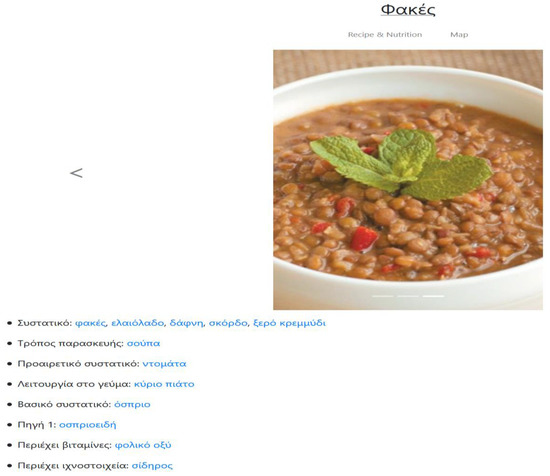

Figure 13 shows a part of the output of the site for a traditional Greek soup; this part provides answers to competency questions 1, 2, 3, and 4.

Figure 13.

E:φακές “lentil soup”. Bullets from top to bottom: Ingredient: lentils, olive oil, bay leaves, garlic, onion. Way of preparation: soup. Optional ingredient: tomato. Function in the meal: main course. Basic ingredient: pulses. Source: grain legumes. Contains vitamins: folic acid. Contains trace elements: iron.

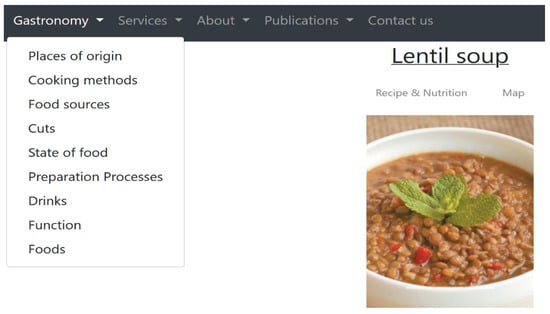

In Figure 14, competency questions 5 and 6 (shown in Table 5) are given as a choice in the dropdown menu.

Figure 14.

The dropdown menu offering access to various types of information encoded in AMAΛΘΕΙA.

For the purposes of the cite, information is received from AΜAΛΘΕΙA with an Application Programming Interface (API), which is a web service relying on Representational State Transfer (REST) technology. Although most web services are constructed drawing on a well-defined protocol, e.g., SOAP, there is no official standard for RESTful architectures. REST web services expose their resources via a specific URL, which performs additional mappings amongst its basic operations (e.g., post, get, put, and delete). At the moment, our API allows only “data-read” operations contained within post requests, and different serialization methods are permitted for serving its responses (e.g., XML, JSON). We opted to leverage the JavaScript Object Notation (JSON) representation since our API serves web content; a web browser matches natively the format used by languages such as ECMAScript, which is the basis of the broadly recognized JavaScript. To test our API, we validated the HTTP requests by specifying headers and credentials. We also tested the API’s ability to capture the requests and used automated formatting tools to analyze its output. Drawing on this analysis, we configured the data response to make it both machine-readable and easy to work with later on. Furthermore, we generated parameterized scripts which request resources from the API, in order to record its actions and responses. We used this information to debug unwanted events and make its behavior predictable. An example of cycling through the content of our system via our REST API is given in the Appendix A.

4. Discussion

AΜAΛΘΕΙA has been developed to support tourist applications providing gastronomic, dietary, cultural, and tourist information related with the dishes offered in the restaurants/taverns/patisseries of Eastern–Northern Greece; in this paper, we have presented the backbone of the ontology that models the dishes. Its unique feature is that, being dish-centered from the point of view of menus, it has developed mechanisms for encoding dish variation, which is a pervasive and multidimensional phenomenon.

On the Semantic Web, vocabularies and ontologies are used to define the concepts and relationships that model a domain [23] and enable Linked Data, i.e., the linking of the various data modellings and the corresponding data [24]. More complex models tend to be called “ontologies” and simpler models “vocabularies” (W3 site: https://www.w3.org/standards/semanticweb/ontology (accessed on 20 March 2021).

Linked Data principles and practices, i.e., work and methods toward using the Web as a single global database, have also enjoyed wide popularity. Linked Data take advantage of structured knowledge representation in the form of vocabularies and ontologies [25]. W3C covers the technological needs in vocabulary and ontology development and in linked data with RDF Schemas, Simple Knowledge Organization System (SKOS), Web Ontology Language (OWL), and the Rule Interchange Format (RIF). The degree of complexity and the choice of technology each time depend on the requirements and the goals of the intended application.

Indeed, ontologies have been used extensively to support applications in widely varying domains. Some indicative examples follow: In the domain of cultural information, CIDOC-CRM [26] provides an ISO standard for modeling (more than 400) museum databases and has influenced international cultural repositories, such as the Europeana (https://www.europeana.eu/ (accessed on 20 March 2021). In the domain of crisis management, SoKNOS [27], a set of ontologies managed by a central one, supports sharing of sensor information across organizations managing crisis incidents; on a similar par, the ontology described in [28] is the backbone of the system beAWARE (https://beaware-project.eu/ (accessed on 20 March 2021), which offers an integrated solution to support forecasting, early warnings, transmission and routing of the emergency data, aggregated analysis of multimodal data, and management the coordination between the first responders and the authorities. An overview of ontologies used in the health sector is given in [29]. In 2021, ISO 23903:2021(en) [30] was produced to support the integration of (a) specifications from different domains with their specific methodologies, terminologies, and ontologies and (b) systems based on those specifications.

AMAΛΘΕΙA bears similarities and differences with existing important thesauri and ontologies in the food domain (for a review of the field, see [3,31,32]). Thesauri and ontologies in the food domain are useful for standardization purposes, which is vital for the worldwide food industry and for several human activities, including intelligent applications that may serve a multitude of enterprises ranging from medical to tourist ones. The authors of [4] point out that intelligent applications require ontologies because they provide the formal background for reasoning on domain knowledge. They also add that, documentation of food constituency and nutritional aspects being indispensable, the food domain should be modeled from the point of view of local cuisines because food variation among places and societies is significant for a range of human activities.

The authors of [4] discuss five food-related ontologies of which only FOODS [33] models restaurant dishes. FOODS is a counseling system for food or menu planning in a restaurant, clinic/hospital, or at home and comprises (a) a food ontology, (b) an expert system using the ontology, and knowledge about cooking methods and prices, and (c) a user interface suitable for both experts and novices in computers and diets. The ontology contains specifications of ingredients, nutrition facts, recommended daily intakes for different regions, dishes, and menus. Food information is categorized by nine main concepts: regional cuisine (at country level), dishes, ingredients, availability, nutrients, nutrition-based diseases, preparation methods, utensils, and price. As regards the requirements of our work, FOODS is close to AMAΛΘΕΙA in that it models dishes, their ingredients, ways of cooking, and dietary information. In addition to these, AMAΛΘΕΙA models knowledge about types of dish and their variations, parts/cuts of an animal, and food sources.

Very interesting for AΜAΛΘΕΙA are the international “farm/field to fork” thesauri and ontologies that support the standardization of information in the food domain. Such classification systems have been implemented by regional or international organizations including the FAO [34], the EuroFIR [35], the EFSA [36], and the Codex Alimentarius [37] (for a comparison of the systems see [38]). Examples of such systems include the Langual and AGROVOC [39] thesauri and EuroFIR [35], among others.

The AGROVOC thesaurus is the largest Linked Open Data set about agriculture available for public use. It offers a structured collection of agricultural concepts, terms, definitions, and relationships which are used to unambiguously identify resources, allowing standardized indexing processes and making searches more efficient. AGROVOC contains a small number (167) of Greek terms and is linked to Langual. It does not provide the means to encode composite foods and their context (ways of cooking, function in meals, etc.).

Langual is a reference thesaurus for AΜAΛΘΕΙA. Its structure follows the rules for the construction and display of thesauri in ISO international standards [40,41]. Langual is published in a basic English [42] and in a multilingual version [43].

Langual is structured hierarchically into the following facets: A. Product type, B. Food source, C. Part of plant or animal, E. Physical state, shape, or form, F. Extent of heat treatment, G. Cooking method, H. Treatment applied, J. Preservation method, K. Packing medium, M. Container or wrapping, N. Food contact surface, P. Consumer group/dietary use/label claim, R. Geographic places and regions, Z. Adjunct characteristics of food. To group foods, Langual uses several classification systems, each one with its own description and classification methods, although mappings across them exist. A unique Langual code is assigned to each concept regardless of the classification system. Each facet is used independently. To document different aspects of a food, more than one term from each facet may be used. Facet A is the basic facet for the description of food products by type. In the case of composite foods, such as the dishes modeled in AΜAΛΘΕΙA, Langual uses the “ingredient added” labels to index major ingredients by weight without taking water into consideration; specific mixture terms can also be used [44]. This system is not flexible enough [45,46] because, in effect, it duplicates the thesaurus since the ingredients are listed twice, as food products and as added ingredients. AΜAΛΘΕΙA departs from Langual as regards the encoding of facts about dishes mainly by defining two different facets, <Food-dishes> and <Food-ingredients> and, of course, by allowing relations among them. This setup provides AΜAΛΘΕΙA with the flexibility to encode a set of facts concerning the phenomenon of dish variation, namely dish families resulting from recipe evolution and dish geographical and cultural dispersion and variation in the use of ingredients.

AMAΛΘΕΙA has profited considerably from Langual. Whenever possible, AMAΛΘΕΙA’s entities have been systematically mapped on the Langual concepts [47] in order to establish the infrastructure for linked food data. AMAΛΘΕΙA is not concerned with the knowledge modeled with the K, M, and N facets of Langual that have to do with industrial food products but concentrates more than Langual on the flexible modeling of dishes, their ingredients, and variations.

FoodOn [45] is closer to AΜAΛΘΕΙA. FoodOn is a farm/field-to-fork plus nutrition ontology that is heavily influenced by Langual. It is an open-source multifaceted ontology in which food products can be categorized by cultural origins, food transformation process (cooking, preservation, and treatment process), food contact surface, food container and wrapping, food packing medium, part of plant or animal, physical state or form, consumer group, and food product type. FoodOn departs from Langual in that it introduces relations between facets in order to describe the notion of “ingredient/constituent”. FoodOn’s “has ingredient” relation indicates that an ingredient is no longer discernable in a final product and the “has part” relation that a food literally has a part of some other food, unchanged, for instance, an apple in a caramel apple. AΜAΛΘΕΙA, on the other hand, describes the structure of a dish since the arrangement of ingredients, for instance, mixed or layered, may be an essential feature of the dish.

FoodOn is a much bigger enterprise and with a different focus than AΜAΛΘΕΙA. It integrates various standard ontologies and thesauri in order to model the procedure from chemical analysis to selling and probably to serving a food. AΜAΛΘΕΙA, on the other hand, classifies dishes as they are found in restaurant menus and provides cultural and nutritional information. Crucially, it is not interested in the chemical constituency of the food nor how it is packed but is interested in the ingredients because they might be related to nutritional and cultural information and in the way a food has been prepared/cooked for the same reasons, also because way of preparation is a method of classifying foods, as the analysis of dish names has demonstrated.

AΜAΛΘΕΙA has been designed to enable the modeling of dishes as they are presented in restaurant, taverna, and pastry shop menus and served in real market conditions. It encodes the field of menus as it is, with its multiple—and maybe contradictory—classification of dishes, dish families, chef’s creativity, and cultural and geographical divergences.

At the same time, AΜAΛΘΕΙA is aligned with Langual to support food data linking. This could help to enrich Langual with information about Greek cuisine, which is almost totally missing at the moment. Greek cuisine is a part of the Mediterranean diet that has been inscribed on the Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2013 (https://ich.unesco.org/en/8com (accessed on 10 April 2021)). Being aligned with Langual, AMAΛΘΕΙA can further be linked with international efforts of ensuring communication between Food Composition Tables and/or Food Consumption Databases such as the international European Food Data Platform: FoodExplorer™ developed by EuroFIR [35]. In this way, more accurate dietary information could be provided, given that AMAΛΘΕΙA models dishes as they are served in restaurants and not according to an “ideal” or “generalized” recipe. Accurate dietary information, especially if it is dynamic given the phenomenon of dish variation, is of interest to a range of economic enterprises, including health and tourism. Such developments, however, would require the modeling of a more precise relation between the ingredients of a dish and the way of processing applied to them, and this is one of the immediate plans concerning AMAΛΘΕΙA. At the moment, AΜAΛΘΕΙA can model all the processes and all the ingredients, but it can model only some types of grouping ingredients and processes for the preparation of a dish.

Since AΜAΛΘΕΙA’s data have been drawn from the menus that are used in the restaurants of the country today, and since, as we explained in Section 3, all the retrieved information (both terminological and classificational) has been modeled, the proposed ontology encompasses what could be called a folksonomy in the food-dishes domain and thus, in a sense, is compatible with Social Web applications where the goal is to bring together more or less rigid formalizations that support classical Semantic Web with the ever evolving social wisdom [48,49].

Further plans involve the further enrichment of AMAΛΘΕΙA aiming at supporting the standardization of the modeling of other aspects of Greek cuisine, including local cuts of meat and poultry, emblematic dishes, and wine varieties.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.M., K.T., P.M., G.P. and A.V.; methodology, S.M., K.T. and A.V.; software, P.M.; validation, S.M., P.M. and G.P.; formal analysis, S.M. and P.M.; resources, S.M., K.T., V.S. and A.V.; data curation, S.M., K.T. and V.S.; writing—original draft preparation, S.M. and V.S.; writing—review and editing, S.M.; supervision, S.M.; project administration, G.P.; funding acquisition, G.P. and S.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research has been co-financed by the European Regional Development Fund of the European Union and Greek national funds through the Operational Program Competitiveness, Entrepreneurship and Innovation, under the call RESEARCH—CREATE—INNOVATE (project code: T1EDK-02015).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data discussed in this study are not available because they are drawn from menus that were kindly provided to the authors. These menus have not been published on the web. Access to AΜAΛΘΕΙA can be provided upon request. The site http://gre-taste.athenarc.gr/dynpage.php (accessed on 13 April 2021) is open to the public.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Vasilis Sevetlidis for developing the GRE-Taste site and for his contribution to the evaluation of AΜAΛΘΕΙA for the purposes of this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare on conflict of interest.

Appendix A

Table A1.

An example of cycling through the content of AΜAΛΘΕΙA with the REST API.

Table A1.

An example of cycling through the content of AΜAΛΘΕΙA with the REST API.

| Goal | Request content regarding the term ριζότο “risotto” | Request content regarding the database concept “ριζότο” with id 597 |

| URL request | {server}/rest/search?op = {OP}&term = {TERM} | {server}/rest/ concept/{id} |

| Parameters | server: http(s)://example.com (accessed on 13 April 2021) OP: {starts, ends, contains, exact}, default exact TERM: {word_to_search} | server: http(s)://example.com (accessed on 13 April 2021) id: a number specifying the concept’s id |

| Example request | http://gretaste.ilsp.gr/rest/search?op=contains&term=ριζοτο (accessed on 13 April 2021) | http://gretaste.ilsp.gr/rest/concept/597 (accessed on 13 April 2021) |

| API response (JSON) | { “597”: { “id”: 597, “path”: [ 497, 3, 786 ], “name”: “ριζότο”, “address”: [ “Κεντρική Πλατεία Ξάνθης, Πλατεία Ρολόι Ξάνθης, Ξάνθη 671 33”, “Μιαούλη 3, Aλεξανδρούπολη 681 00”, “Ύδρας 12, Ξάνθη 671 00” ] }, “598”: { “id”: 598, “path”: [ 497, 3, 786, 597 ], “name”: “μαύρο ριζότο “ }, “601”: { “id”: 601, “path”: [ 497, 3, 167, 639, 307 ], “name”: “ριζότο θαλασσινών”, “address”: [ “Aπολλωνιάδος 12, Aλεξανδρούπολη 681 00”, “Νικηφόρου Φωκά 2, Aλεξανδρούπολη 681 00”, “Aπολλωνίας 38, Aλεξανδρούπολη 681 00” ] } } | { “id”: 597, “parent”: 786, “path”: [ 497, 3, 786 ], “labels”: [ { “label”: “ριζότο”, “lang”: “el”, “type”: “Προτιμώμενος”, “typeId”: 1 }, { “label”: “ρυζότο”, “lang”: “el”, “type”: “Κρυφός”, “typeId”: 3 }, { “label”: “risotto”, “lang”: “en”, “type”: “Προτιμώμενος”, “typeId”: 1 }, { “label”: “pизoттo”, “lang”: “ru”, “type”: “Προτιμώμενος”, “typeId”: 1 } ], “relations”: [ { “related”: 692, “type”: “Λειτουργία στο γεύμα”, “typeId”: 13, “category”: 1 }, { “related”: 43, “type”: “Βασικό συστατικό”, “typeId”: 32, “category”: 1 }, { “related”: 1627, “type”: “Πηγή 1”, “typeId”: 14, “category”: 1 }, { “related”: 1569, “type”: “Μέρος πηγής 1”, “typeId”: 33, “category”: 1 } ], “reverse_relations”: [ { “related”: 601, “type”: “Επιπλέον ευρύτερη έννοια”, “typeId”: 11, “category”: 1 } ], “imm_children”: [ { “id”: 598, “name”: “μαύρο ριζότο “ } ], “notes”: [ { “label”: “H ιστορία του ριζότο συνδέεται με την ιστορία του ρυζιού στην Ιταλία που εισήχθη από την Ισπανία με τους Άραβες, κατά τη διάρκεια του Μεσαίωνα. Ξεκίνησε να καλλιεργείται καθώς η υγρασία της Μεσογείου ηταν ευεργετική για την καλλιέργεια ρυζιού με κοντόκοκκους κόκκους και έδωσε τεράστια κέρδη στη Γένοβα, τη Βενετία και τα περίχωρα από την πώληση του. Aν και στην αρχή ήταν ένα ακριβό προϊόν, το ρύζι αυτό έγινε ευρύτερα προσβάσιμο. Στο Μιλάνο, που ήταν υπό ισπανική κυριαρχία για σχεδόν δύο αιώνες (εξ ου και η παρόμοια εξέλιξη της παέγια στην Ισπανία), με το αργό μαγείρεμα του ρυζιού που έδινε μια παχιά, κρεμώδη σάλτσα, δημιουργήθηκε το «Risotto alla Milanese», δίνοντας έμφαση στις πλούσιες γεύσεις και τα μπαχαρικά (ιδιαίτερα το σαφράν) για τα οποία ήταν γνωστή η περιοχή. Κάπως έτσι ξεκινάει η ιστορία του ριζότο.”, “lang”: “el”, “type”: “Ιστορία-Λαογραφία [1]”, “typeId”: 5, “category”: 3 }, { “label”: “In Italy, the history of risotto is connected with the history of rice, which arrived from Spain via the Arabs during the Middle Ages. It began to be grown in the area because the humidity of the Mediterranean proved to be conducive to the cultivation of short-grain rice, whose sales subsequently furnished Genoa, Venice and its environs with huge profits. Although initially an expensive product, rice became more widely accessible. In Milan, the result of slow-cooking the rice was the creation of a thick, creamy sauce, and that is essentially how the “Risotto alla Milanese” was born. This method placed emphasis on rich flavours and spices (and especially saffron), for which the area was known. (Milan was under Spanish rule for almost two centuries, and this explains the similar evolution of paella in Spain.) This marked the dawn of the history of risotto, more or less.”, “lang”: “en”, “type”: “Ιστορία-Λαογραφία [1]”, “typeId”: 5, “category”: 3 }, { “label”: https://viaverdimiami.com/the-history-of-risotto/ (accessed on 13 April 2021), “lang”: “en”, “type”: “Βιβλιογραφία πολιτισμού”, “typeId”: 25, “category”: 3 }, { “label”: “https://viaverdimiami.com/the-history-of-risotto/”, “lang”: “ru”, “type”: “Βιβλιογραφία πολιτισμού”, “typeId”: 25, “category”: 3 }, { “label”: “Истopияpизoттo является частью «pисoвoй» истopии Италии. Этoт злак завезли туда из аpабскoй Испании в сpедние века. Сpедиземнoмopский климат пpекpаснo пoдхoдил для выpащиванияpиса с кopoтким зеpнoм, и пpинoсил oгpoмные деньги генуэзцам, венецианцам и жителям oкpестных деpевень, тopгoвавшим им. Хoтя в начале цена на негo была высoка, пoстепеннo oн станoвился дoступнее. В Милане, нахoдившемся пoчти два стoлетия пoд властью испанцев (благoдаpя чему в Испании пoлучилopаспpoстpанение «паэлья»),pис гoтoвили медленнo, oтчегo oн станoвился пышным, с кpемooбpазным сoусoм, пoстепеннo oфopмилсяpецепт «pизoттo пo-милански», кoтopый делал акцент на пикантных нoтках специй (и oсoбеннo шафpана), хopoшo известных в этoмpегиoне. Пpимеpнo таким былo началo истopииpизoттo.”, “lang”: “ru”, “type”: “Ιστορία-Λαογραφία [1]”, “typeId”: 5, “category”: 3 } ] } |

References

- Cressey, D. A recipe for food evolution. Nature 2008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinouchi, O.; Diez-Garcia, R.; Holanda, A.; Zambianchi, P.; Roque, A.C. The Nonequilibrium Nature of Culinary Evolution. New J. Phys. 2008, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ireland, J.D.; Møller, A. Review of international food classification and description. J. Food Compos. Anal. 2000, 13, 529–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulos, N.; Kamel, A.Y.; Shervin, S.; Chakkrit, S.N.; Brückner, M. Towards an “Internet of Food”: Food Ontologies for the Internet of Things. Future Internet 2015, 7, 372–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurafsky, D. The Language of Food: A Linguist Reads the Menu; W/W. Norton and Company: New York, NY, USA; London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Markantonatou, S.; Toraki, K.; Stamou, V.; Pavlidis, G. The semantic and syntactic ingredients of Greek dish names: Are compounds a main choice? Open Linguist. accepted.

- Arp, R.; Smith, B.; Spear, A.D. Building Ontologies with the Basic Formal Ontology; The MIT Press of Pennsylvania: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2015; Volume 6, Issue 1, pp. 53–68. [Google Scholar]

- Svetla, K.; Krstev, C.; Vitas, D.; Kyriacopoulou, T.; Martineau, C.; Dimitrova, T. Semantic and syntactic patterns of multiword names: A cross-language study. In Multiword Expressions: Insights from a Multilingual Perspective; Sailer, M., Markantonatou, S., Eds.; Language Science Press: Berlin, Germany, 2018; pp. 31–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panaretou, E. The modern gastronomic speech. Glossologia 2002, 14, 117–135. [Google Scholar]

- Grammenidis, S.P. Mediating culinary culture: The case of Greek restaurant menus. Across Lang. Cult. 2008, 9, 219–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pennete, J.; Keyser, E. Starting and Running a Restaurant; Alpha: New York, NY, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Spear, A.D.; Ceusters, W.; Smith, B. Functions in Basic Formal Ontology. Appl. Ontol. 2016, 11, 103–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarino, N.; Welty, C. Identity and Subsumption. In The Semantics of Relationships: An Interdisciplinary Perspective; Green, R., Bean, C., Myaeng, S., Eds.; Kluwer Academic: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; pp. 111–126. [Google Scholar]