Awareness and Perceptions of “Age-Friendly”: Analyzing Survey Results from Voices in the United States

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Population

2.2. Survey Design, Administration, and Analysis

2.3. Ethical Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Respondent Demographics

3.2. Survey Findings

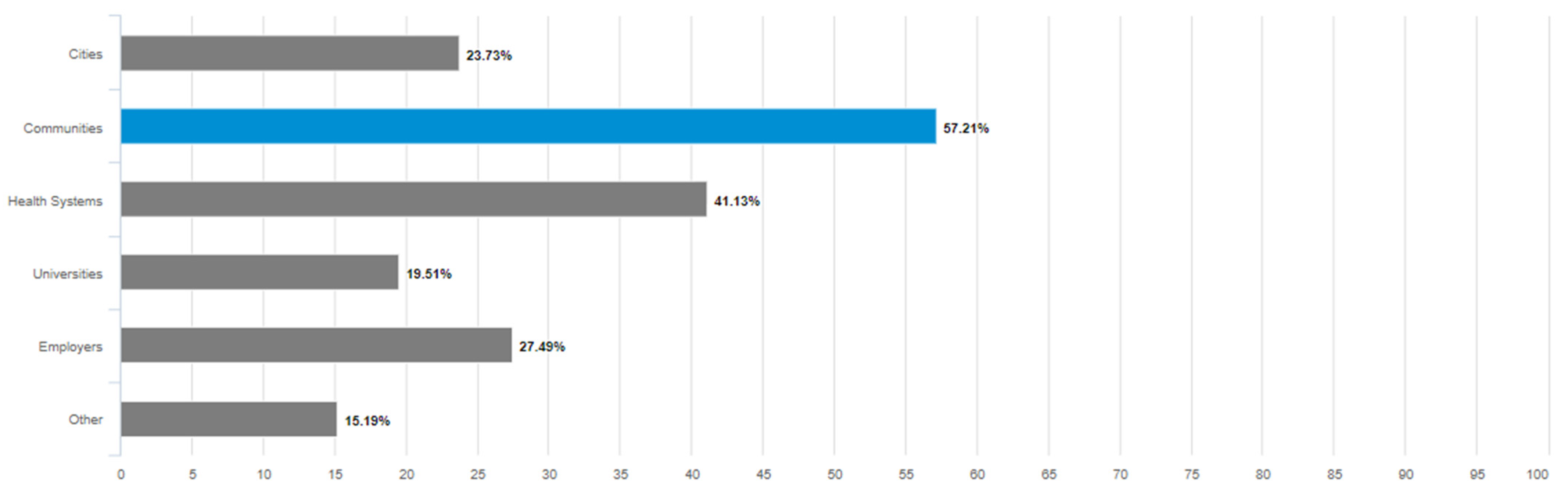

3.2.1. The Level of General Awareness of the Term “Age-Friendly” and in What Context(s)

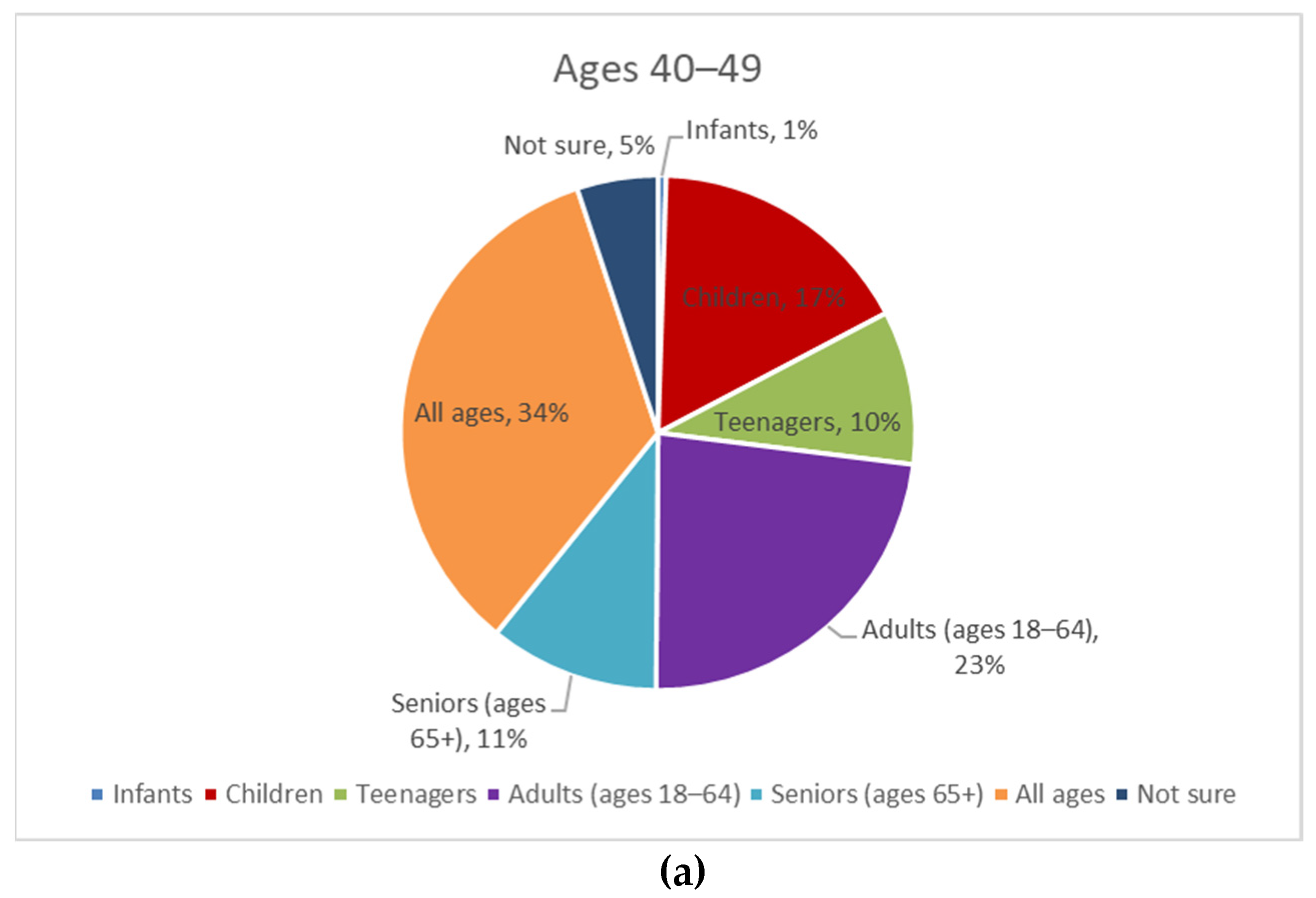

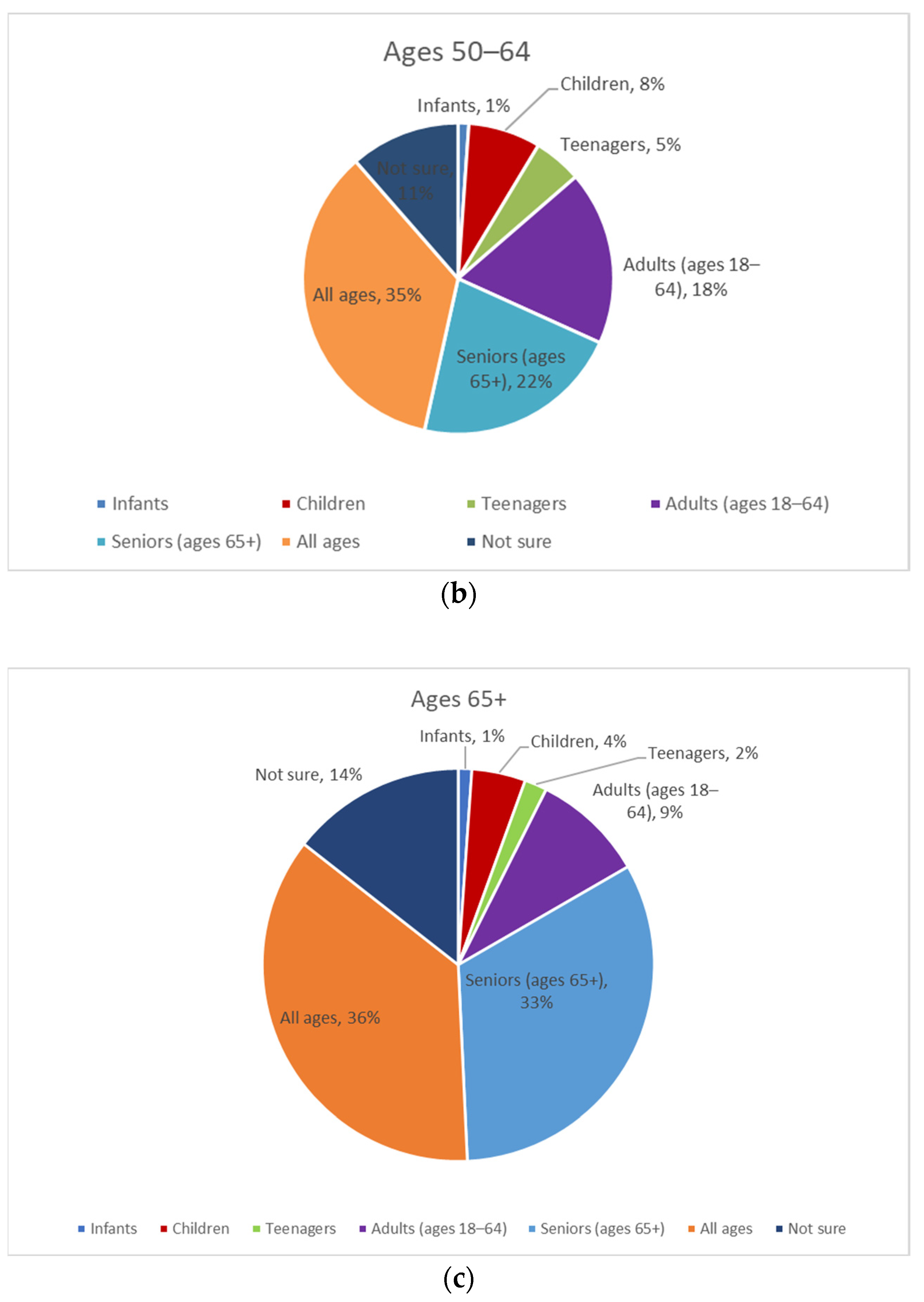

3.2.2. The Perceived Understanding of the Age Range to Which the Term “Age-Friendly” Applies

3.2.3. The General Context for “____-Friendly Designations” in Respondents’ Minds and Whether Other Aging-Related Phrases in the Field Are Mentioned Unaided

3.2.4. The Influence That “Age-Friendly” May Have on Consumer Preferences and Decision Making

3.2.5. The Degree to Which Individuals Have Taken Action Regarding Their Advance Care Planning

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- How would you rate your awareness of the term “age-friendly”?

- Extremely aware

- Moderately aware

- Somewhat aware

- Slightly aware

- Not at all aware

- How would you rate the general public’s awareness of the term “age-friendly”?

- Extremely aware

- Moderately aware

- Somewhat aware

- Slightly aware

- Not at all aware

- What age range do you think the term “age-friendly” applies?

- Infants

- Children

- Teenagers

- Adults (18–64)

- Seniors (ages 65+)

- All ages

- Not sure

- When you hear the term “Age-Friendly,” what is at least one word or short phrase that comes to mind that describes the term?

- In what context have you heard the term “age-friendly” used to describe something (check all that apply)?

- Cities

- Communities

- Health Systems

- Universities

- Employers

- Other (please describe): ________

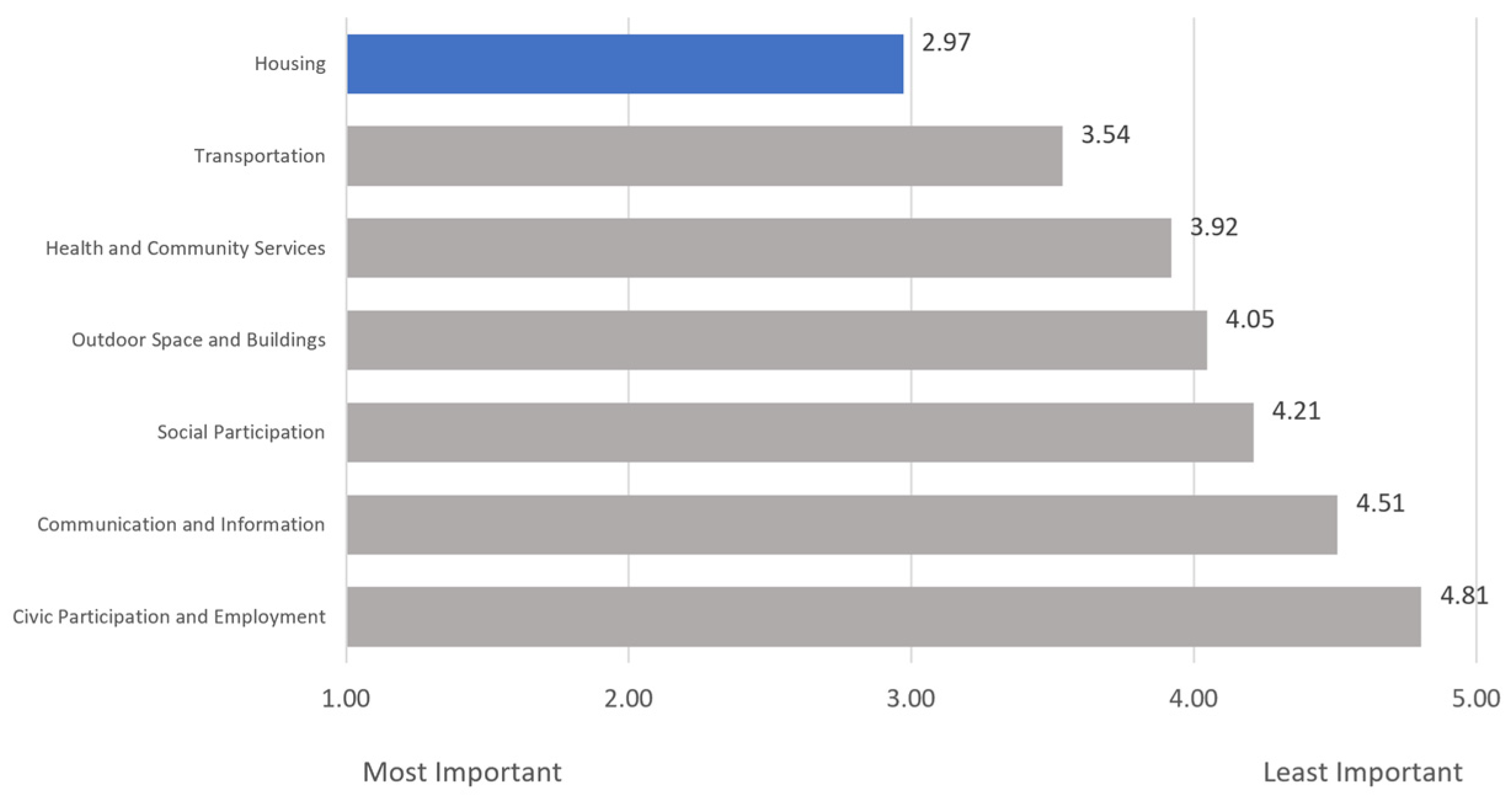

- An age-friendly community is a place that adapts its services and physical structures to be more inclusive and receptive to the needs of its population to improve their quality of life as they age. Rank, in order of importance to you, factors that age-friendly communities should have.

- Transportation: safe, reliable, and affordable. Easy-to-use public transportation, walking and biking paths, and rideshare options.

- Housing: various options and a network of home-based care and service options to allow older adults to remain in their homes.

- Outdoor space and buildings: accessible parks and green spaces, safe streets and sidewalks, and buildings that all can enjoy, including residents with mobility challenges.

- Social participation: opportunities for older adults to engage in life-long learning, social, and cultural activities.

- Civic participation and employment: support services for older adults to find paid jobs and volunteer opportunities.

- Communication and information: systems designed to provide older adults with access to information that can help them and their care partners as they age.

- Health and community services: affordable care that aligns with older adults’ health outcome goals and preferences whether care is delivered in medical or community settings or at home

- If you were to see or hear the term “age-friendly community,” how much would it influence your decision to live in that community?

- Extremely influential

- Very influential

- Somewhat influential

- Slightly influential

- Not at all influential

- Which items or activities below have you thought about or taken action on in the last five years?

| Item or Activity | Taken Action | Thought About but Not Taken Action | Have Not Thought About Taking Action |

| Having a care plan in the event of a serious illness or action | |||

| Documentation of your health care preferences in the event you may no longer be able to make decisions for yourself | |||

| Appointed someone to be your care “proxy” or the person who will make care decisions for you in case you may no longer be able to do so for yourself | |||

| Ensuring you have copies or access to your health records |

- 9.

- Have you heard the phrase ___-friendly in other contexts?

- Yes

- No

- Not sure

- 10.

- If yes, please name the context.

- What is your gender?

- ○

- Female

- ○

- Male

- ○

- Other (please specify)

- What is your age?

- ○

- 40–49

- ○

- 50–64

- ○

- 65–74

- ○

- 75–84

- ○

- 85+

- What is your race or ethnicity?

- ○

- Asian

- ○

- Black or African American

- ○

- Hispanic or Latino

- ○

- Middle Eastern or North African

- ○

- Multiracial or Multiethnic

- ○

- Native American or Alaska Native

- ○

- White

- ○

- Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander

- ○

- Self-describe ____

- Please select your geographical area.

- ○

- Urban–By definition, an urban area is the region surrounding a city. Urban areas are very developed, meaning there is a density of human structures such as houses, commercial buildings, roads, bridges, and railways. Urban area can refer to towns, cities, and suburbs.

- ○

- Suburban–By definition, a suburban area is a cluster of properties, primarily residential, that are not densely compacted, yet located very near an urban area. Also referred to as the “suburbs,” these areas are often located just outside of larger metro areas but can span even further.

- ○

- Rural–By definition, a rural area, often called “the country,” has a low population density and large amounts of undeveloped land.

- What is your highest level of education?

- ○

- Some high school

- ○

- High school

- ○

- Some college

- ○

- Trade/vocational/technical

- ○

- Associate’s

- ○

- Bachelor’s

- ○

- Master’s

- ○

- Professional

- Doctorate

- Accounting

- ○

- Agriculture

- ○

- Apparel

- ○

- Biotech

- ○

- Communications

- ○

- Consulting

- ○

- Education

- ○

- Energy

- ○

- Engineering

- ○

- Entertainment

- ○

- Environmental

- ○

- Finance

- ○

- Food and Beverage

- ○

- Government

- ○

- Healthcare

- ○

- Hospitality

- ○

- Insurance

- ○

- Law

- ○

- Manufacturing

- ○

- Media

- ○

- Nonprofit

- ○

- Other

- ○

- Pharmaceutical

- ○

- Real Estate

- ○

- Retail/Shipping

- ○

- Technology

- ○

- Telecommunications

- ○

- Transportation

- ○

- Utilities

- If healthcare is selected, please specify your sub-industry identification:

- ○

- Administration

- ○

- Research

- ○

- Biomedical

- ○

- Government

- ○

- Media

- ○

- Patient Advocacy

- ○

- Insurance

- ○

- Health System

- ○

- Health Plan

- ○

- Provider

- ○

- Philanthropy

References

- Ortman, J.M.; Velkoff, V.A.; Hogan, H. An Aging Nation: The Older Population in the United States; United States Census Bureau: Washington, DC, USA, 2014. Available online: https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2014/demo/p25-1140.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Beard, J. The Age-Friendly Communities Movement: History, Update, and the Future. Innov. Aging 2017, 1 (Suppl. 1), 757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization (WHO). Global Age-Friendly Cities: A Guide; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2007; Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/43755 (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- AARP Network of Age-Friendly States and Communities: The Member List. Available online: https://www.aarp.org/livable-communities/network-age-friendly-communities/info-2014/member-list.html (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- AARP. AARP Network of Age-Friendly States and Communities: An Age-Friendly Community Is Livable for People of All Ages; AARP: Washington, DC, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.aarp.org/content/dam/aarp/livable-communities/age-friendly-network/2023/NAFSC%20Intro%20Handout-singles-2023-3-17.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Kim, K.; Buckley, T.D.; Burnette, D.; Kim, S.; Cho, S. Measurement Indicators of Age-Friendly Communities: Findings from the AARP Age-Friendly Community Survey. Gerontologist 2022, 62, e17–e27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, K.; Buckley, T.D.; Burnette, D.; Huang, J.; Kim, S. Age-Friendly Communities and Older Adults’ Health in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 9292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, Y.J. Age-Friendly Features in Home and Community and the Self-Reported Health and Functional Limitation of Older Adults: The Role of Supportive Environments. J. Urban Health 2020, 97, 471–485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tiraphat, S.; Peltzer, K.; Thamma-Aphiphol, K.; Suthisukon, K. The Role of Age-Friendly Environments on Quality of Life among Thai Older Adults. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2017, 14, 282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehning, A.J.; Smith, R.J.; Dunkle, R.E. Age-Friendly Environments and Self-Rated Health: An Exploration of Detroit Elders. Res. Aging 2014, 36, 72–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cramm, J.M.; van Dijk, H.M.; Nieboer, A.P. The Importance of Neighborhood Social Cohesion and Social Capital for the Well Being of Older Adults in the Community. Gerontologist 2013, 53, 142–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Age-Friendly Primary Health Care Centres Toolkit; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008; Available online: https://extranet.who.int/agefriendlyworld/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/WHO-Age-friendly-Primary-Health-Care-toolkit.pdf (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Tavares, J.; Santinha, G.; Rocha, N.P. Age-Friendly Health Care: A Systematic Review. Healthcare 2021, 9, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Biasi, A.; Wolfe, M.; Carmody, J.; Fulmer, T.; Auerbach, J. Creating an Age-Friendly Public Health System. Innov. Aging 2020, 4, igz044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- What Is an Age-Friendly Health System? Available online: https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Pages/default.aspx (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Age-Friendly Health Systems Initiative. Available online: https://www.johnahartford.org/grants-strategy/current-strategies/age-friendly/age-friendly-health-systems-initiative (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Age-Friendly Health Systems Initiative Marks Milestone. Available online: https://www.aha.org/news/headline/2023-03-16-age-friendly-health-systems-initiative-marks-milestone (accessed on 11 April 2023).

- Fulmer, T.; Reuben, D.B.; Auerbach, J.; Fick, D.M.; Galambos, C.; Johnson, K.S. Actualizing Better Health and Health Care for Older Adults. Health Aff. 2021, 40, 219–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Torku, A.; Chan, A.; Yung, E. Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: A Review and Future Directions. Ageing Soc. 2021, 41, 2242–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forsyth, A.; Lyu, Y. Making Communities Age-Friendly: Lessons from Implemented Programs. J. Plan. Lit. 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Greenfield, E.A. Using Ecological Frameworks to Advance a Field of Research, Practice, and Policy on Aging-in-Place Initiatives. Gerontologist 2012, 52, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, A.; Welch-Stockton, J.; Kim, J.Y.; Canham, S.L.; Greer, V.; Sorweid, M. Age-Friendly Community Interventions for Health and Social Outcomes: A Scoping Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2023, 20, 2554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The Prevention Research Centers Healthy Aging Research Network. Prev. Chronic Dis. 2006, 3, A17. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1500966/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Kochtitzky, C.S.; Freeland, A.L.; Yen, I.H. Ensuring mobility-supporting environments for an aging population: Critical actors and collaborations. J. Aging Res. 2011, 2011, 138931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rémillard-Boilard, S.; Buffel, T.; Phillipson, C. Developing Age-Friendly Cities and Communities: Eleven Case Studies from Around the World. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2021, 18, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- The John, A. Hartford Foundation (JAHF). Driving toward Age-Friendly Care for the Future; JAHF: New York, NY, USA, 2019; Available online: https://img.webmd.com/vim/live/webmd/consumer_assets/site_images/sponsored_programs/toc-aging-well/infographic.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Lesser, S.; Zakharkin, S.; Louie, C.; Escobedo, M.R.; Whyte, J.; Fulmer, T. Clinician Knowledge and Behaviors Related to the 4Ms Framework of Age-Friendly Health Systems. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2022, 70, 789–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mehegan, L.; Rainville, C. 2021 AARP Survey on the Perceptions Related to a Dementia Diagnosis: Adults Age 40+; AARP Research: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long-Term Care in America: Increasing Access to Care. The Long-Term Care Poll. Available online: https://www.longtermcarepoll.org/project/long-term-care-in-america-increasing-access-to-care/ (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI). Age-Friendly Health Systems: Guide to Using the 4Ms in the Care of Older Adults; IHI: Boston, MA, USA, 2020; Available online: https://www.ihi.org/Engage/Initiatives/Age-Friendly-Health-Systems/Documents/IHIAgeFriendlyHealthSystems_GuidetoUsing4MsCare.pdf (accessed on 15 April 2023).

- What Is Dementia Friendly America? Available online: https://www.dfamerica.org/what-is-dfa (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Age-Friendly Cities and Communities. Available online: https://www3.paho.org/hq/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=13765:age-friendly-cities&Itemid=0&lang=en#gsc.tab=0 (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- AARP Network of Age-Friendly States and Communities: Welcome to the AARP Network of Age-Friendly States and Communities. Available online: https://www.aarp.org/livable-communities/network-age-friendly-communities/ (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Fulmer, T.; Mate, K.S.; Berman, A. The Age-Friendly Health System Imperative. J. Am. Geriatr. Soc. 2018, 66, 22–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yadav, K.N.; Gabler, N.B.; Cooney, E.; Kent, S.; Kim, J.; Herbst, N.; Mante, A.; Halpern, S.D.; Courtright, K.R. Approximately One in Three US Adults Completes Any Type of Advance Directive For End-of-Life Care. Health Aff. 2017, 36, 1244–1251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- National Population by Characteristics: 2020–2022. US Census Bureau. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-national-detail.html (accessed on 15 April 2023).

| Characteristic | Number of Responses (%) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| 40–49 | 393 (38.45%) |

| 50–64 | 359 (35.13%) |

| 65–74 | 196 (19.18%) |

| 75–84 | 65 (6.36%) |

| 85+ | 9 (0.88%) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 616 (60.27%) |

| Male | 406 (39.73%) |

| Other | 0 (0%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | |

| Asian | 27 (2.64%) |

| Black or African American | 103 (10.08%) |

| Hispanic or Latino | 46 (4.5%) |

| Middle Eastern or North African | 1 (0.1%) |

| Multiracial or Multiethnic | 5 (0.49%) |

| Native American or Alaska Native | 19 (1.86%) |

| White | 811 (79.35%) |

| Self-Describe | 9 (0.88%) |

| Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander | 1 (0.1%) |

| Geographical Area | |

| Urban | 310 (30.33%) |

| Suburban | 471 (46.09%) |

| Rural | 241 (23.58%) |

| Prompt | Perceived Awareness (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely Aware | Moderately Aware | Somewhat Aware | Slightly Aware | Not at All Aware | |

| How would you rate your awareness of the term “age-friendly”? | |||||

| Overall | 28% | 31% | 22% | 8% | 12% |

| 40–49 | 42% | 31% | 17% | 4% | 6% |

| 50–64 | 19% | 30% | 25% | 9% | 16% |

| 65–74 | 17% | 34% | 23% | 11% | 14% |

| 75–84 | 18% | 26% | 28% | 15% | 12% |

| 85+ | 11% | 11% | 56% | 11% | 11% |

| How would you rate the general public’s awareness of the term “age-friendly”? | |||||

| Overall | 14% | 25% | 32% | 16% | 12% |

| 40–49 | 24% | 34% | 24% | 10% | 8% |

| 50–64 | 9% | 21% | 36% | 18% | 16% |

| 65–74 | 9% | 20% | 37% | 20% | 13% |

| 75–84 | 3% | 12% | 37% | 31% | 17% |

| 85+ | 22% | 0% | 67% | 0% | 11% |

| Prompt | Level of Influence (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extremely Influential | Very Influential | Somewhat Influential | Slightly Influential | Not at All Influential | |

| If you were to see or hear the term “age-friendly community,” how much would it influence your decision to live in that community? | |||||

| Overall | 22% | 25% | 33% | 9% | 12% |

| 40–49 | 31% | 25% | 27% | 6% | 10% |

| 50–64 | 16% | 25% | 36% | 10% | 13% |

| 65–74 | 15% | 26% | 40% | 10% | 10% |

| 75–84 | 17% | 22% | 32% | 11% | 18% |

| 85+ | 22% | 11% | 11% | 33% | 22% |

| Prompt | Taken Action (%) | Thought About but Not Taken Action (%) | Have Not Thought About Taking Action (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Male | Female | Male | Female | Male | Female | |

| Having a care plan in the event of a serious illness or action | 39% | 27% | 40% | 48% | 21% | 25% |

| Documentation of your health care preferences in the event you may no longer be able to make decisions for yourself | 39% | 28% | 39% | 47% | 22% | 25% |

| Appointed someone to be your care “proxy” or the person who will make care decisions for you in case you may no longer be able to do so for yourself | 40% | 33% | 33% | 39% | 26% | 28% |

| Ensuring you have copies or access to your health records | 46% | 41% | 33% | 37% | 21% | 22% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Dunning, L.; Ty, D.; Shah, P.; McDermott, M. Awareness and Perceptions of “Age-Friendly”: Analyzing Survey Results from Voices in the United States. Geriatrics 2023, 8, 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics8030058

Dunning L, Ty D, Shah P, McDermott M. Awareness and Perceptions of “Age-Friendly”: Analyzing Survey Results from Voices in the United States. Geriatrics. 2023; 8(3):58. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics8030058

Chicago/Turabian StyleDunning, Lauren, Diane Ty, Priyanka Shah, and Mac McDermott. 2023. "Awareness and Perceptions of “Age-Friendly”: Analyzing Survey Results from Voices in the United States" Geriatrics 8, no. 3: 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics8030058

APA StyleDunning, L., Ty, D., Shah, P., & McDermott, M. (2023). Awareness and Perceptions of “Age-Friendly”: Analyzing Survey Results from Voices in the United States. Geriatrics, 8(3), 58. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics8030058