Group Reminiscence Therapy for Dementia to Improve Well-Being and Reduce Behavioral Symptoms

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Contents of Group Reminiscence Therapy

2.3. Measurements of Assessment Items and Participants

2.3.1. Study Participants

2.3.2. PGC Morale Scale to Assess Subjective Well-Being

2.3.3. HDS-R for Assessment of Cognitive Function

2.3.4. NPI-NH for Assessed BPSD

2.4. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. General Results

3.2. Change in HDS-R Score for Repeated Measures

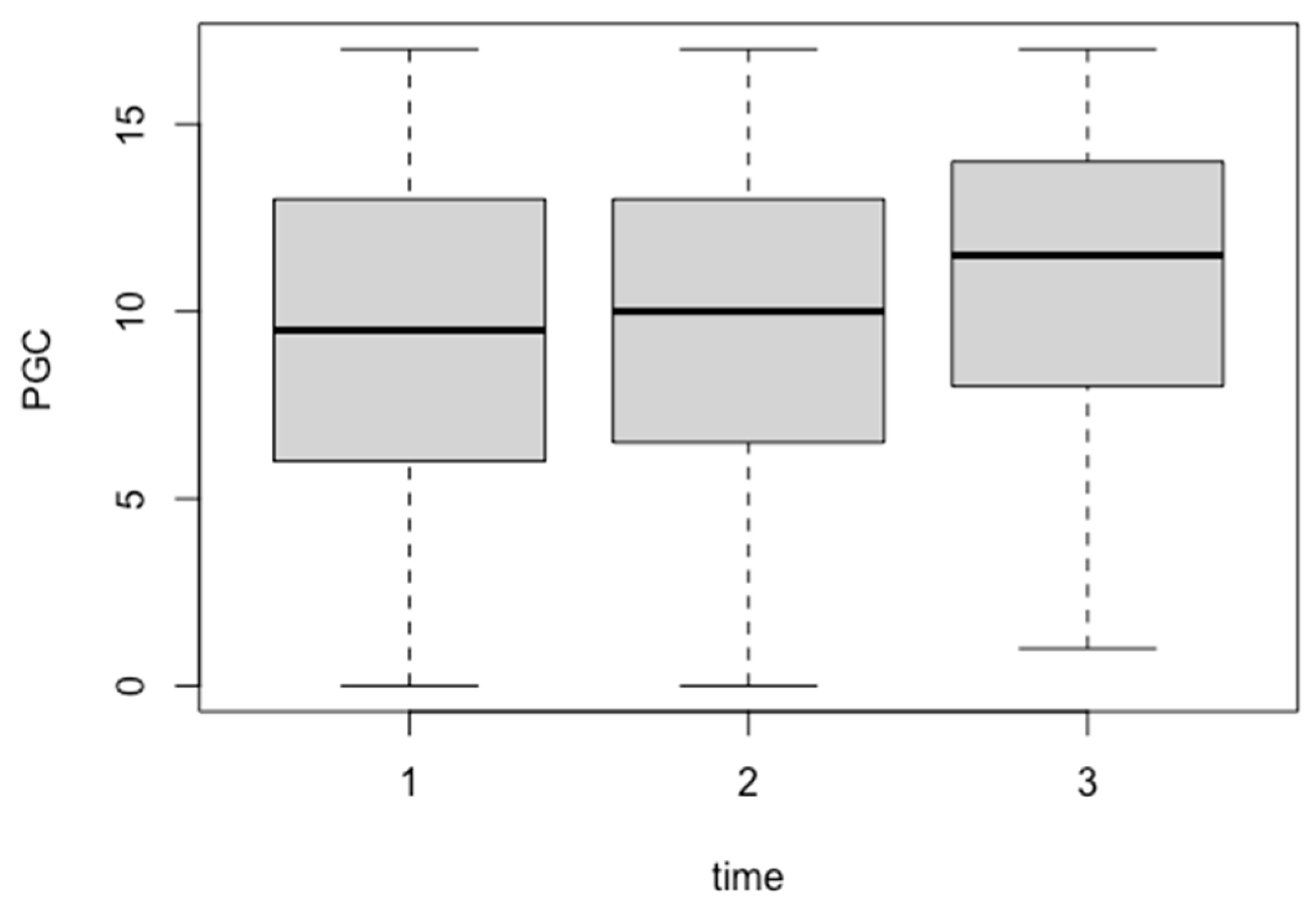

3.3. Change in PGC Morale Scale Score for Repeated Measures

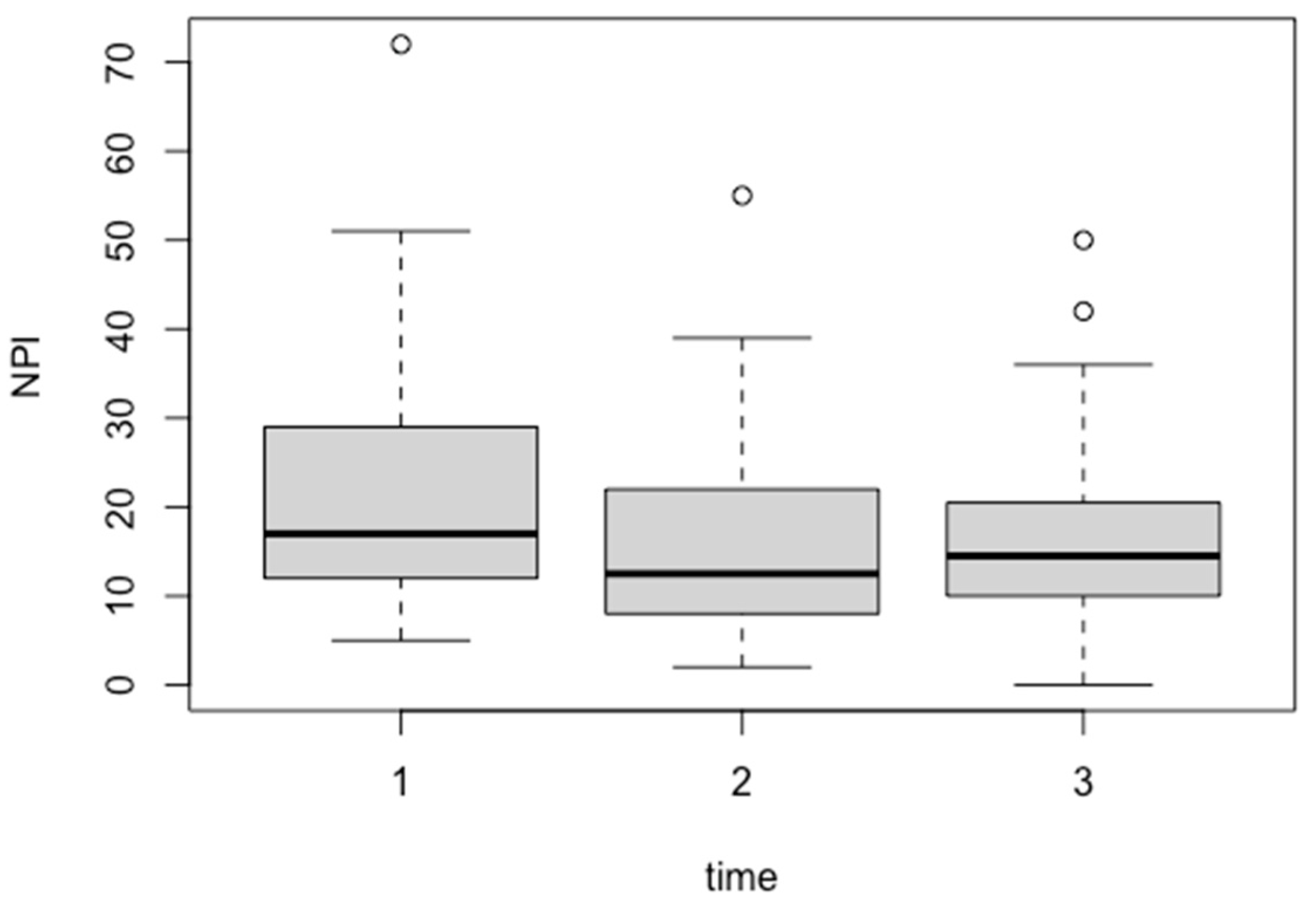

3.4. Change in NPI-NH Score for Repeated Measures

4. Discussion

4.1. Effect on Cognitive Function

4.2. Effect on Subjective Well-Being

4.3. Effect on Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms

4.4. Generalization of Findings

4.5. Study Limitations and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- World Health Organization (WHO). Dementia. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan Comprehensive Promotion of Dementia Policies. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/content/12300000/000519620.pdf (accessed on 3 July 2024).

- Montgomery, W.; Jorgensen, M.; Stathis, S.; Cheng, Y.; Nakamura, T. Epidemiology, Associated Burden, and Current Clinical Practice for the Diagnosis and Management of Alzheimer’s Disease in Japan. Clinicoecon. Outcomes Res. 2017, 10, 13–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borumandnia, N.; Majd, H.A.; Khadembashi, N.; Olazadeh, K.; Alaii, H. Worldwide Patterns in Alzheimer’s Disease and Other Dementias Prevalence from 1990 to 2017: A Growth Mixture Models Approach. Res. Sq. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, R.G. Working Memory in Alzheimer-Type Dementia. Neuropsychology 1994, 8, 544–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwertner, E.; Pereira, J.B.; Xu, H.; Secnik, J.; Winblad, B.; Eriksdotter, M.; Nagga, K.; Religa, D. Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia in Different Dementia Disorders: A Large-Scale Study of 10 000 Individuals. bioRxiv 2021, bioRxiv:2021.06.24.21259454. [Google Scholar]

- Kwon, C.-Y.; Lee, B. Prevalence of Behavioral and Psychological Symptoms of Dementia in Community-Dwelling Dementia Patients: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 741059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butler, R.N. The Life Review: An Interpretation of Reminiscence in the Aged. Psychiatry 1963, 26, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, B.; Spector, A.; Jones, C.; Orrell, M.; Davies, S. Reminiscence Therapy for Dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2005, 2005, CD001120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, K.-J.; Chu, H.; Chang, H.-J.; Chung, M.-H.; Chen, C.-H.; Chiou, H.-Y.; Chou, K.-R. The Effects of Reminiscence Therapy on Psychological Well-Being, Depression, and Loneliness among the Institutionalized Aged. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2010, 25, 380–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meléndez Moral, J.C.; Fortuna Terrero, F.B.; Sales Galán, A.; Mayordomo Rodríguez, T. Effect of Integrative Reminiscence Therapy on Depression, Well-Being, Integrity, Self-Esteem, and Life Satisfaction in Older Adults. J. Posit. Psychol. 2015, 10, 240–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yanagida, N.; Yamaguchi, T.; Matsunari, Y. Evaluating the Impact of Reminiscence Therapy on Cognitive and Emotional Outcomes in Dementia Patients. J. Pers. Med. 2024, 14, 629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, K.; Lee, S.; Yang, J.; Song, T.; Hong, G.-R.S. A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis on the Effect of Reminiscence Therapy for People with Dementia. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2019, 31, 1581–1597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ministry of Health, Labour, Welfare 7. Rating of Dementia. Available online: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hss/dl/siel-2010-04.pdf (accessed on 8 May 2024).

- Lawton, M.P. Environment and Other Determinants of Well-Being in Older People. Gerontologist 1983, 23, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Imai, Y.; Hasegawa, K. The Revised Hasegawa’s Dementia Scale (HDS-R)-Evaluation of Its Usefulness as a Screening Test for Dementia. Hong Kong J. Psychiatry 1994, 4, 20–24. [Google Scholar]

- Honjo, Y.; Kawasaki, I.; Nagai, K.; Harada, S.; Ogawa, N. Characteristics of Patients with Alzheimer’s Disease Who Score Higher on the Revised Hasegawa’s Dementia Scale than on the Mini-Mental State Examination: Implications for Screening. Psychogeriatrics 2023, 23, 742–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shigenobu, K.; Hirono, N.; Tabushi, K.; Ikeda, M. Validity and reliability of the Japanese version of the neuropsychiatric Inventory-Nursing Home Version (NPI-NH). Brain Nerve 2008, 60, 1463–1469. [Google Scholar]

- Lange, R.T.; Hopp, G.A.; Kang, N. Psychometric Properties and Factor Structure of the Neuropsychiatric Inventory Nursing Home Version in an Elderly Neuropsychiatric Population. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2004, 19, 440–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cummings, J.L.; Mega, M.; Gray, K.; Rosenberg-Thompson, S.; Carusi, D.A.; Gornbein, J. The Neuropsychiatric Inventory: Comprehensive Assessment of Psychopathology in Dementia. Neurology 1994, 44, 2308–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An Analysis of Variance Test for Normality (Complete Samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591–611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolker, B.M.; Brooks, M.E.; Clark, C.J.; Geange, S.W.; Poulsen, J.R.; Stevens, M.H.H.; White, J.-S.S. Generalized Linear Mixed Models: A Practical Guide for Ecology and Evolution. Trends Ecol. Evol. 2009, 24, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, X.A.; Donaldson, L.; Correa-Cano, M.E.; Evans, J.; Fisher, D.N.; Goodwin, C.E.D.; Robinson, B.S.; Hodgson, D.J.; Inger, R. A Brief Introduction to Mixed Effects Modelling and Multi-Model Inference in Ecology. PeerJ 2018, 6, e4794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woods, B.; Rai, H.K.; Elliott, E.; Aguirre, E.; Orrell, M.; Spector, A. Cognitive Stimulation to Improve Cognitive Functioning in People with Dementia. Cochrane Libr. 2023, 2023, CD005562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahar-Fuchs, A.; Clare, L.; Woods, B. Cognitive Training and Cognitive Rehabilitation for Mild to Moderate Alzheimer’s Disease and Vascular Dementia. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2013, 2013, CD003260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spector, A.; Thorgrimsen, L.; Woods, B.; Royan, L.; Davies, S.; Butterworth, M.; Orrell, M. Efficacy of an Evidence-Based Cognitive Stimulation Therapy Programme for People with Dementia: Randomised Controlled Trial. Br. J. Psychiatry 2003, 183, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.-J. Group Reminiscence Therapy for Cognitive and Affective Function of Demented Elderly in Taiwan. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2007, 22, 1235–1240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.-C.; Dai, Y.-T.; Hwang, S.-L. The Effect of Reminiscence on the Elderly Population: A Systematic Review. Public Health Nurs. 2003, 20, 297–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawachi, I.; Berkman, L.F. Social Ties and Mental Health. J. Urban Health 2001, 78, 458–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, K.; Wakefield, J.R.H.; Sani, F. Identification with Social Groups Is Associated with Mental Health in Adolescents: Evidence from a Scottish Community Sample. Psychiatry Res. 2015, 228, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyketsos, C.G.; Carrillo, M.C.; Ryan, J.M.; Khachaturian, A.S.; Trzepacz, P.; Amatniek, J.; Cedarbaum, J.; Brashear, R.; Miller, D.S. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimers. Dement. 2011, 7, 532–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, D.W.; Ames, D.; Gardner, B.; King, M. Psychosocial Treatments of Behavior Symptoms in Dementia: A Systematic Review of Reports Meeting Quality Standards. Int. Psychogeriatr. 2009, 21, 225–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subramaniam, P.; Woods, B. The Impact of Individual Reminiscence Therapy for People with Dementia: Systematic Review. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2012, 12, 545–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, F. The Past in the Present: Using Reminiscence in Health and Social Care; Health Professions Press: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2004; ISBN 9781878812872. [Google Scholar]

- Thorgrimsen, L.; Schweitzer, P.; Orrell, M. Evaluating Reminiscence for People with Dementia: A Pilot Study. Arts Psychother. 2002, 29, 93–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.-C.; Chang, S.-M.; Lee, W.-L.; Lee, M.-S. The Effects of Group Music with Movement Intervention on Agitated Behaviours of Institutionalized Elders with Dementia in Taiwan. Complement. Ther. Med. 2006, 14, 113–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livingston, G.; Kelly, L.; Lewis-Holmes, E.; Baio, G.; Morris, S.; Patel, N.; Omar, R.Z.; Katona, C.; Cooper, C. Non-Pharmacological Interventions for Agitation in Dementia: Systematic Review of Randomised Controlled Trials. Br. J. Psychiatry 2014, 205, 436–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cammisuli, D.M.; Cipriani, G.; Giusti, E.M.; Castelnuovo, G. Effects of Reminiscence Therapy on Cognition, Depression and Quality of Life in Elderly People with Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Randomized Controlled Trials. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 5752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosenberg, P.B.; Mielke, M.M.; Appleby, B.; Oh, E.; Leoutsakos, J.-M.; Lyketsos, C.G. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in MCI Subtypes: The Importance of Executive Dysfunction. Int. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2011, 26, 364–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olazarán, J.; Reisberg, B.; Clare, L.; Cruz, I.; Peña-Casanova, J.; Del Ser, T.; Woods, B.; Beck, C.; Auer, S.; Lai, C.; et al. Nonpharmacological Therapies in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review of Efficacy. Dement. Geriatr. Cogn. Disord. 2010, 30, 161–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statistics | HDS-R | PGC Morale Scale | NPI-NH | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Follow-up 1 | Follow-up 2 | Baseline | Follow-up 1 | Follow-up 2 | Baseline | Follow-up 1 | Follow-up 2 | |

| n | 49 | 46 | 47 | 48 | 47 | 44 | 49 | 46 | 44 |

| Mean | 9.59 | 10.35 | 9.79 | 9.29 | 9.94 | 10.41 | 22.08 | 15.8 | 16.5 |

| SD | 5.42 | 5.86 | 6.62 | 4.55 | 4.33 | 4.28 | 14.39 | 10.59 | 10.25 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 32.9108 | 41.5993 | 0.791 | 0.43 |

| Age | −0.2073 | 0.4744 | −0.437 | 0.663 |

| Evaluation time points | 0.2102 | 2.745 | 0.077 | 0.939 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 4.86173 | 10.36497 | 0.469 | 0.6412 |

| Age | 0.04603 | 0.119 | 0.387 | 0.7007 |

| Evaluation time points | 0.54813 | 0.26531 | 2.066 | 0.0417 |

| Estimate | Std. Error | t-Value | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Intercept) | 22.48368 | 27.43798 | 0.819 | 0.41675 |

| Age | 0.01429 | 0.31482 | 0.045 | 0.96401 |

| Evaluation time points | −2.66017 | 0.84646 | −3.143 | 0.00226 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Yanagida, N.; Yamaguchi, T.; Matsunari, Y. Group Reminiscence Therapy for Dementia to Improve Well-Being and Reduce Behavioral Symptoms. Geriatrics 2024, 9, 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9050109

Yanagida N, Yamaguchi T, Matsunari Y. Group Reminiscence Therapy for Dementia to Improve Well-Being and Reduce Behavioral Symptoms. Geriatrics. 2024; 9(5):109. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9050109

Chicago/Turabian StyleYanagida, Nobuhiko, Takumi Yamaguchi, and Yuko Matsunari. 2024. "Group Reminiscence Therapy for Dementia to Improve Well-Being and Reduce Behavioral Symptoms" Geriatrics 9, no. 5: 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9050109

APA StyleYanagida, N., Yamaguchi, T., & Matsunari, Y. (2024). Group Reminiscence Therapy for Dementia to Improve Well-Being and Reduce Behavioral Symptoms. Geriatrics, 9(5), 109. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics9050109