Trichoderma and Mycosynthesis of Metal Nanoparticles: Role of Their Secondary Metabolites

Abstract

:1. Introduction

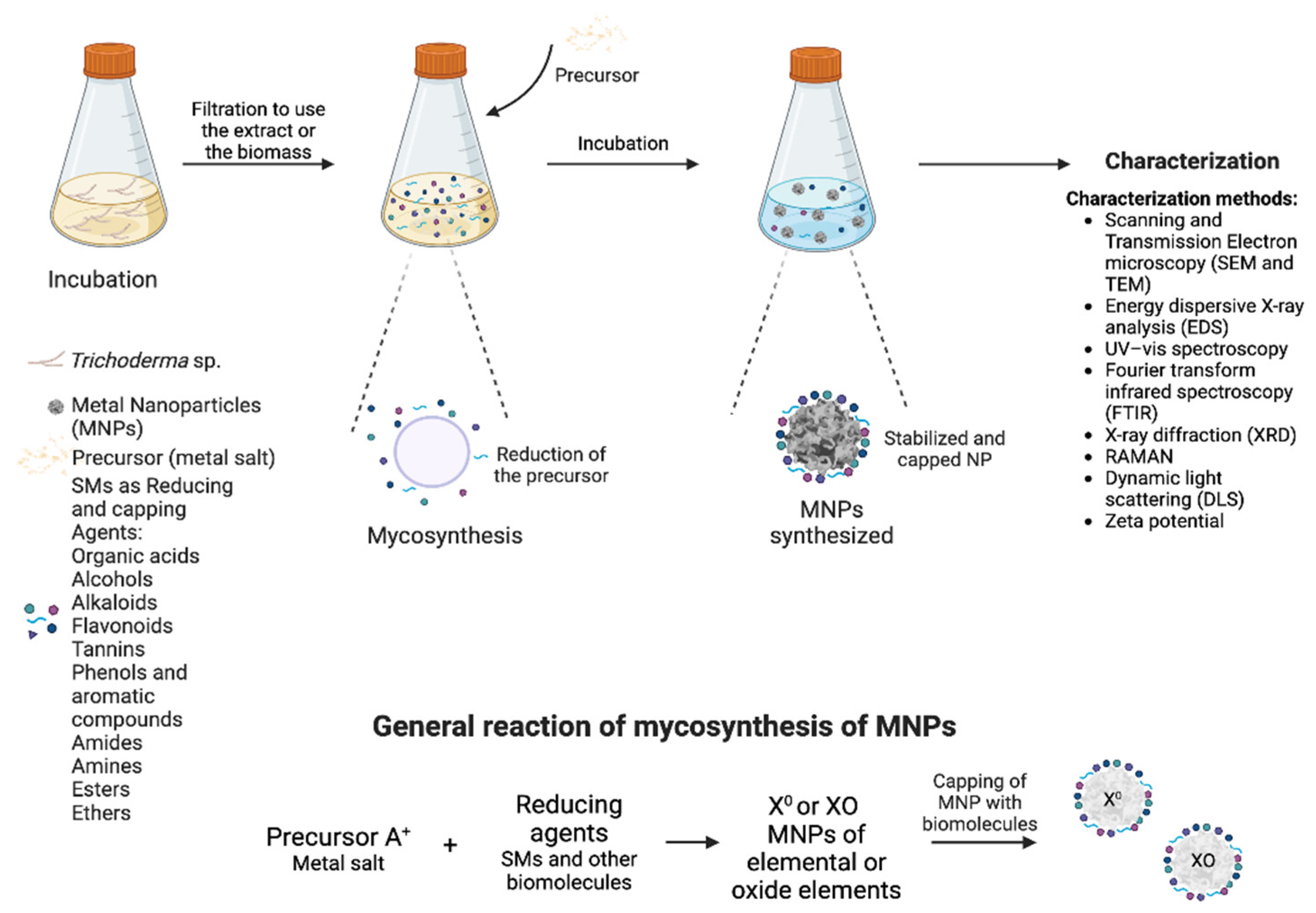

2. Mechanism of Green Synthesis of MNPs by Fungi

3. Main Secondary Metabolites from Trichoderma Involved in the Synthesis of Nanoparticles

| MNPs | SMs Involved or Suggested to Be Involved in the Biosynthesis | Type of NP/Size of the NP (nm) | Methods of Characterization | Trichoderma Species | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag | 55 exometabolites: alkane, dicarboxylic acid, aromatic ketone, amino acid, heteroacyclic compound, ketose sugar, sugars alcohol, aliphatic amine, polyol compound, steroidal pheromone, carbocyclic sugars groups | Spherical/ 59.66 | SEM, EDAX, Zeta potential, PSA, UV–vis and FTIR | Trichoderma fusant Fu21 | [30] |

| Ag | Compounds with –OH group of phenols, alkyne groups, N-H of amine groups, –CH3 of aromatic and aliphatic compounds and –C–O stretch of alcohols, carboxylic acids, and esters | Spherical or polyhedral/ 5–50 | Electron microscopy, EDS, UV–vis, FTIR and XRD | T. longibranchiatum | [45] |

| Amide I and amide II-like compounds and primary amines | Spherical/10 | UV–vis, TEM, FTIR, DLS and Zeta potential | T. longibranchiatum | [46] | |

| Kojic, acetic and citric acid | Spherical/20 | UV–vis and TEM | T. harzianum | [47] | |

| 1-benzoyl-3-[(S)-((2DS, 4R, 8R)-8-ethylquinuclidin-2-yl] (6-methoxyquinolin-4-yl)methyl)thiourea, puerarin, genistein, isotalatizidine and ginsenoside | Not determined/21.49 | UV–vis, FTIR, EDS, DLS, XRD and SEM | T. harzianum | [48] | |

| Alkaloids, flavonoids, tannins, and phenols | Roughly spherical/ 12.7 | XRD, TEM, SEM, EDX and FTIR | T. harzianum | [49] | |

| Biomolecules with hydroxyl, alkane, amide, and carboxylate groups | Spherical, triangular and cuboid/5 to 11 | DLS, XRD, FTIR, FESEM and HRTEM | T. longibrachiatum | [50] | |

| Compounds with primary and secondary amines | Triangular and spherical/ 50–75 | UV–vis, XRD, FTIR, SEM and EDAX | T. atroviride | [51] | |

| Biochemicals with carbonyl, CH3 and alcohol groups | Spherical/ 15–20 | UV–vis, FTIR and SEM | T. viride and T. longibraciatum | [53] | |

| Biomolecules with amine, amide, carbonyl, phenols, methylene, and alcohol groups | Roughly spherical/5–35 | UV–vis, XRD, TEM and FTIR | Trichoderma strains | [54] | |

| Alkaline, amine and aromatic peptides | Anisotropic structural/ 15–25 | FTIR, TEM, EDX | T. atroviride | [55] | |

| Secondary metabolites with aromatic, amide I and carbonyl groups | Spherical/ 50–100 | UV–vis, FTIR, SEM, EDX, XRD and Zeta potential | T. citrinoviride | [56] | |

| Au | Molecules with methyl, amide, and amine groups | Spherical, hexagonal, and octagonal/ 20–50 | XRD, FTIR, SEM-EDS, DLS and Zeta potential | T. harzianum | [42] |

| Compounds with primary and secondary amines | Triangular nanoplates and spherical/ 50–75 | UV–vis, XRD, FTIR, SEM and EDAX | T. atroviride | [51] | |

| Cu/CuO | Secondary metabolites with amide and aromatic groups | Spherical/110 | FTIR, XRD, SEM, TEM and XPS | T. asperellum | [57] |

| Primary amines, secondary amines, aliphatic amines, and amide groups | Spherical/ 8–100 | UV-vis, FTIR and SEM | T. virens | [58] | |

| ZnO | Secondary metabolites with carboxylic acid, amide, esters, ethers, and phenolic groups | Spherical or polyhedral/15–30.32 | UV-vis, FTIR, EDX, XRD, SEM and TEM | T. longibranchiatum | [52] |

4. Secondary Metabolites from Trichoderma Acting as Capping Agents in MNPs

| MNPs | SMs Involved or Suggested to Act as Capping | Type of NP/Size of the NP (nm) | Trichoderma Species | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ag | Exometabolites: alkanes, aromatic alcohol, ketones, phenolic compounds, saturated fatty acids, furans, heterocyclen, steroid, sugar acids, acyclic alkanes, fatty alcohol, aromatic hydrocarbons, esters, and sulfur-containing compounds | Spherical/59.66 | Trichoderma fusant Fu21 | [30] |

| Aromatic secondary metabolites | Not determined/21.49 | T. harzianum | [48] | |

| Biomolecules with hydroxyl, alkane, amide, and carboxylate groups | Spherical, triangular and cuboid/5–11 | T. longibrachiatum | [50] | |

| Compounds with primary and secondary amines | Triangular nanoplates and spherical/50–75 | T. atroviride | [51] | |

| Biochemicals with carbonyl, CH3 and alcohol groups | Spherical/15–20 | T. viride and T. longibraciatum | [53] | |

| Biomolecules with amine, amide, carbonyl, phenols, methylene, and alcohol groups | Roughly spherical/5–35 | Trichoderma strains | [54] | |

| Secondary metabolites with aromatic, amide I and carbonyl groups | Spherical/50–100 | T. citrinoviride | [56] | |

| Compounds with alkane, phosphine, amide and aromatic ketones, aliphatic bending, silica, cycloalkane, aromatic mono-substitution and alkynes functional groups | Spherical/43.68 | T. harzianum | [62] | |

| Carbohydrate, and heterocyclic compound molecules, especially, gliotoxin molecule | Spherical and oval/5–50 | T. virens | [75] | |

| Au | Biomolecules containing amide I and amide II groups | Spherical and pseudo-spherical/9.8 | Trichoderma sp. | [40] |

| Molecules with methyl, amide, and amine groups | Spherical, hexagonal, and octagonal/20–50 | T. harzianum | [42] | |

| Compounds with primary and secondary amines | Triangular nanoplates and spherical/50–75 | T. atroviride | [51] | |

| Cu/CuO | Secondary metabolites with amide and aromatic groups | Spherical/110 | T. asperellum | [57] |

| Primary amines, secondary amines, aliphatic amines, and amide groups | Spherical/8–100 | T. virens | [58] | |

| MnO | Phenols, alkaloids, carbohydrates, and amino acids | Rod/35 | T. virens | [70] |

| Fe/FeO3 | Compounds with alkene, carboxyl, and phenol groups | Not determined | Trichoderma strains | [41] |

| Molecules with amide, alcohol, esters, ethers, and aromatic groups | Spherical/185 | T. harzianum | [72] | |

| Compounds with amide I and amide II groups | Spherical/25 | T. asperellum | [76] | |

| SiO2 | Molecules with different functional groups of biomolecules | Oval, rod and cubical/89 | T. harzianum | [74] |

| TiO2 | Molecules with carbonyl groups | Triangular, pentagonal, spherical and rod/10–400 | T. citrinoviride | [64] |

| Molecules with different functional groups: alkane, methylene, alkene, amine, and carboxylic acid | Roughly spherical/74.4 | T. viride | [66] | |

| ZnO | Mycochemicals with phenolic, amino acids, aldehydes, and ketone functional groups | Hexagonal, spherical and rod/8–25 | Trichoderma sp. | [68] |

5. Research Gaps and Future Directions in the Mycosynthesis of Nanoparticles Mediated by Trichoderma and Their SMs

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Home|National Nanotechnology Initiative. Available online: https://www.nano.gov/ (accessed on 8 March 2024).

- Hussain, I.; Singh, N.B.; Singh, A.; Singh, H.; Singh, S.C. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles and Its Potential Application. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 545–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Xu, H.; Chen, Z.-S.; Chen, G. Biosynthesis of Nanoparticles by Microorganisms and Their Applications. J. Nanomater. 2011, 2011, e270974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, B.; Santra, K.; Pattnaik, G.; Ghosh, S. Preparation, Characterization and in-Vitro Evaluation of Sustained Release Protein-Loaded Nanoparticles Based on Biodegradable Polymers. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2008, 3, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chhipa, H. Chapter 5—Mycosynthesis of Nanoparticles for Smart Agricultural Practice: A Green and Eco-Friendly Approach. In Green Synthesis, Characterization and Applications of Nanoparticles; Shukla, A.K., Iravani, S., Eds.; Micro and Nano Technologies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 87–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Owaid, M.N.; Ibraheem, I.J. Mycosynthesis of Nanoparticles Using Edible and Medicinal Mushrooms. Eur. J. Nanomed. 2017, 9, 5–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madakka, M.; Jayaraju, N.; Rajesh, N. Mycosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Characterization. MethodsX 2018, 5, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azmath, P.; Baker, S.; Rakshith, D.; Satish, S. Mycosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Bearing Antibacterial Activity. Saudi Pharm. J. 2016, 24, 140–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elsakhawy, T.; Omara, A.E.-D.; Abowaly, M.; El-Ramady, H.; Badgar, K.; Llanaj, X.; Törős, G.; Hajdú, P.; Prokisch, J. Green Synthesis of Nanoparticles by Mushrooms: A Crucial Dimension for Sustainable Soil Management. Sustainability 2022, 14, 4328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilger-Casagrande, M.; Germano-Costa, T.; Pasquoto-Stigliani, T.; Fraceto, L.F.; de Lima, R. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Employing Trichoderma harzianum with Enzymatic Stimulation for the Control of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 14351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roy, L.; Bera, D.; Adak, S. Mycosynthesized Nanoparticles: Role in Food Processing Industries; Prasad, R., Kumar, V., Kumar, M., Wang, S., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, F.V.; Musumeci, M.A. Trichoderma as Biological Control Agent: Scope and Prospects to Improve Efficacy. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2021, 37, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, G.E.; Howell, C.R.; Viterbo, A.; Chet, I.; Lorito, M. Trichoderma Species—Opportunistic, Avirulent Plant Symbionts. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2004, 2, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brotman, Y.; Briff, E.; Viterbo, A.; Chet, I. Role of Swollenin, an Expansin-Like Protein from Trichoderma, in Plant Root Colonization. Plant Physiol. 2008, 147, 779–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, F.; Chen, W.; Wei, Z.; Pang, G.; Li, R.; Ran, W.; Shen, Q. Colonization of Trichoderma harzianum Strain SQR-T037 on Tomato Roots and Its Relationship to Plant Growth, Nutrient Availability and Soil Microflora. Plant Soil 2015, 388, 337–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweiger, R.; Padilla-Arizmendi, F.; Nogueira-López, G.; Rostás, M.; Lawry, R.; Brown, C.; Hampton, J.; Steyaert, J.M.; Müller, C.; Mendoza-Mendoza, A. Insights into Metabolic Changes Caused by the Trichoderma virens-Maize Root Interaction. Mol. Plant-Microbe Interact. 2021, 34, 524–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cai, F.; Druzhinina, I.S. In Honor of John Bissett: Authoritative Guidelines on Molecular Identification of Trichoderma. Fungal Divers. 2021, 107, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalamun, M.; Schmoll, M. Trichoderma—Genomes and Genomics as Treasure Troves for Research towards Biology, Biotechnology and Agriculture. Front. Fungal Biol. 2022, 3, 1002161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomah, A.A.; Zhang, Z.; Alamer, I.S.A.; Khattak, A.A.; Ahmed, T.; Hu, M.; Wang, D.; Xu, L.; Li, B.; Wang, Y. The Potential of Trichoderma-Mediated Nanotechnology Application in Sustainable Development Scopes. Nanomaterials 2023, 13, 2475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olmedo-Monfil, V.; Mendoza-Mendoza, A.; Gómez, I.; Cortés, C.; Herrera-Estrella, A. Multiple Environmental Signals Determine the Transcriptional Activation of the Mycoparasitism Related Gene prb1 in Trichoderma atroviride. Mol. Genet. Genomics 2002, 267, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Valdespino, C.A.; Casas-Flores, S.; Olmedo-Monfil, V. Trichoderma as a Model to Study Effector-Like Molecules. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 1030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, E.M.; Howlett, B.J. Secondary Metabolism: Regulation and Role in Fungal Biology. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2008, 11, 481–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmeister, D.; Keller, N.P. Natural Products of Filamentous Fungi: Enzymes, Genes, and Their Regulation. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2007, 24, 393–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermosa, R.; Cardoza, R.E.; Rubio, M.B.; Gutiérrez, S.; Monte, E. Secondary Metabolism and Antimicrobial Metabolites of Trichoderma. In Biotechnology and Biology of Trichoderma; Gupta, V.K., Schmoll, M., Herrera-Estrella, A., Upadhyay, R.S., Druzhinina, I., Tuohy, M.G., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 125–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukherjee, P.K.; Horwitz, B.A.; Kenerley, C.M. Secondary Metabolism in Trichoderma—A Genomic Perspective. Microbiol. Read. Engl. 2012, 158, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeilinger, S.; Gruber, S.; Bansal, R.; Mukherjee, P.K. Secondary Metabolism in Trichoderma—Chemistry Meets Genomics. Fungal Biol. Rev. 2016, 30, 74–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mishra, A.; Kumari, M.; Pandey, S.; Chaudhry, V.; Gupta, K.C.; Nautiyal, C.S. Biocatalytic and Antimicrobial Activities of Gold Nanoparticles Synthesized by Trichoderma Sp. Bioresour. Technol. 2014, 166, 235–242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gemishev, O.; Panayotova, M.; Gicheva, G.; Mintcheva, N. Green Synthesis of Stable Spherical Monodisperse Silver Nanoparticles Using a Cell-Free Extract of Trichoderma reesei. Materials 2022, 15, 481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, P.; Ahmad, A.; Mandal, D.; Senapati, S.; Sainkar, S.R.; Khan, M.I.; Parishcha, R.; Ajaykumar, P.V.; Alam, M.; Kumar, R.; et al. Fungus-Mediated Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Immobilization in the Mycelial Matrix: A Novel Biological Approach to Nanoparticle Synthesis. Nano Lett. 2001, 1, 515–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirpara, D.; Gajera, H.P. Green Synthesis and Antifungal Mechanism of Silver Nanoparticles Derived from Chitin-Induced Exometabolites of Trichoderma Interfusant. Appl. Organomet. Chem. 2019, 34, e5407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guleria, V.; Saxena, J. Bioinspired Trichogenic Silver Nanoparticles and Their Antifungal Activity Against Plant Pathogenic Fungi Sclerotinia sclerotiorum MTCC 8785. Nat. Environ. Pollut. Technol. 2023, 22, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elegbede, J.A.; Lateef, A.; Azeez, M.A.; Asafa, T.B.; Yekeen, T.A.; Oladipo, I.C.; Adebayo, E.A.; Beukes, L.S.; Gueguim-Kana, E.B. Fungal Xylanases-Mediated Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles for Catalytic and Biomedical Applications. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2018, 12, 857–863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elegbede, J.A.; Lateef, A.; Azeez, M.A.; Asafa, T.B.; Yekeen, T.A.; Oladipo, I.C.; Aina, D.A.; Beukes, L.S.; Gueguim-Kana, E.B. Biofabrication of Gold Nanoparticles Using Xylanases Through Valorization of Corncob by Aspergillus niger and Trichoderma longibrachiatum: Antimicrobial, Antioxidant, Anticoagulant and Thrombolytic Activities. Waste Biomass Valorization 2020, 11, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gemishev, O.T.; Panayotova, M.I.; Mintcheva, N.N.; Djerahov, L.P.; Tyuliev, G.T.; Gicheva, G.D. A Green Approach for Silver Nanoparticles Preparation by Cell-Free Extract from Trichoderma reesei Fungi and Their Characterization. Mater. Res. Express 2019, 6, 095040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingle, A.; Gade, A.; Pierrat, S.; Sonnichsen, C.; Rai, M. Mycosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using the Fungus Fusarium acuminatum and Its Activity Against Some Human Pathogenic Bacteria. Curr. Nanosci. 2008, 4, 141–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fayaz, M.; Tiwary, C.S.; Kalaichelvan, P.T.; Venkatesan, R. Blue Orange Light Emission from Biogenic Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles Using Trichoderma viride. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2010, 75, 175–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, D.; Yu, S.; Yu, D.; Liu, N.; Tang, Y.; Fan, Y.; Wang, C.; Wu, A. Biogenic Trichoderma harzianum-Derived Selenium Nanoparticles with Control Functionalities Originating from Diverse Recognition Metabolites against Phytopathogens and Mycotoxins. Food Control 2019, 106, 106748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Hadi, A.; Iqbal, D.; Alharbi, R.; Jahan, S.; Darwish, O.; Alshehri, B.; Banawas, S.; Palanisamy, M.; Ismail, A.; Aldosari, S.; et al. Myco-Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles and Their Bioactive Role against Pathogenic Microbes. Biology 2023, 12, 661. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ramos, M.M.; Dos S Morais, E.; da S Sena, I.; Lima, A.L.; de Oliveira, F.R.; de Freitas, C.M.; Fernandes, C.P.; de Carvalho, J.C.T.; Ferreira, I.M. Silver Nanoparticle from Whole Cells of the Fungi Trichoderma Spp. Isolated from Brazilian Amazon. Biotechnol. Lett. 2020, 42, 833–843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qu, Y.; Shen, W.; Pei, X.; Ma, F.; You, S.; Li, S.; Wang, J.; Zhou, J. Biosynthesis of Gold Nanoparticles by Trichoderma Sp. WL-Go for Azo Dyes Decolorization. J. Environ. Sci. 2017, 56, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kareem, S.; Adeleye, T.; Ojo, R. Effects of pH, Temperature and Agitation on the Biosynthesis of Iron Nanoparticles Produced by Trichoderma Species. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 805, 012036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- do Nascimento, J.M.; Cruz, N.D.; de Oliveira, G.R.; Sá, W.S.; de Oliveira, J.D.; Ribeiro, P.R.S.; Leite, S.G.F. Evaluation of the Kinetics of Gold Biosorption Processes and Consequent Biogenic Synthesis of AuNPs Mediated by the Fungus Trichoderma harzianum. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2021, 21, 101238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nandini, B.; Hariprasad, P.; Prakash, H.S.; Shetty, H.S.; Geetha, N. Trichogenic-Selenium Nanoparticles Enhance Disease Suppressive Ability of Trichoderma against Downy Mildew Disease Caused by Sclerospora graminicola in Pearl Millet. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 2612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.-Y.; Lo, C.-T.; Chen, C.; Liu, M.-Y.; Chen, J.-H.; Peng, K.-C. Efficient Isolation of Anthraquinone-Derivatives from Trichoderma harzianum ETS 323. J. Biochem. Biophys. Methods 2007, 70, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, X.; Zhong, Z.; Xia, R.; Liu, X.; Qin, L. Biosynthesis Optimization of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) Using Trichoderma longibranchiatum and Biosafety Assessment with Silkworm (Bombyx mori). Arab. J. Chem. 2022, 15, 104142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elamawi, R.M.; Al-Harbi, R.E.; Hendi, A.A. Biosynthesis and Characterization of Silver Nanoparticles Using Trichoderma longibrachiatum and Their Effect on Phytopathogenic Fungi. Egypt. J. Biol. Pest Control 2018, 28, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, B.; Mathur, A.; Koul, A.; Shrivastava, V. Study on the Extraction and Purification of Metabolites Obtained from Trichoderma harzianum. Asian J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2019, 5, 547–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konappa, N.; Udayashankar, A.C.; Dhamodaran, N.; Krishnamurthy, S.; Jagannath, S.; Uzma, F.; Pradeep, C.K.; De Britto, S.; Chowdappa, S.; Jogaiah, S. Ameliorated Antibacterial and Antioxidant Properties by Trichoderma harzianum Mediated Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EL-Moslamy, S.H.; Elkady, M.F.; Rezk, A.H.; Abdel-Fattah, Y.R. Applying Taguchi Design and Large-Scale Strategy for Mycosynthesis of Nano-Silver from Endophytic Trichoderma harzianum SYA.F4 and Its Application against Phytopathogens. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 45297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omran, B.A.; Nassar, H.N.; Younis, S.A.; Fatthallah, N.A.; Hamdy, A.; El-Shatoury, E.H.; El-Gendy, N.S. Physiochemical Properties of Trichoderma longibrachiatum DSMZ 16517-Synthesized Silver Nanoparticles for the Mitigation of Halotolerant Sulphate-Reducing Bacteria. J. Appl. Microbiol. 2019, 126, 138–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ponmurugan, P. Biosynthesis of Silver and Gold Nanoparticles Using Trichoderma atroviride for the Biological Control of Phomopsis Canker Disease in Tea Plants. IET Nanobiotechnol. 2017, 11, 261–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghareeb, R.Y.; Belal, E.B.; El-Khateeb, N.M.M.; Shreef, B.A. Utilizing Bio-Synthesis of Nanomaterials as Biological Agents for Controlling Soil-Borne Diseases in Pepper Plants: Root-Knot Nematodes and Root Rot Fungus. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, D.S.; Hiruni Tharaka, W.G.; Wickramarachchi, S.R.; Amarasinghe, D.; De Silva, C.R.; Gunawardana, T.N. Mycosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles (Trichoderma viride, Trichoderma longibrachiatum) and Their Mosquito Larvicidal Efficacy on Dengue Vectors and Acute Toxicity on Moina macrocopa. Asian J. Chem. 2023, 35, 1995–2000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qu, M.; Yao, W.; Cui, X.; Xia, R.; Qin, L.; Liu, X. Biosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles (AgNPs) Employing Trichoderma Strains to Control Empty-Gut Disease of Oak Silkworm (Antheraea pernyi). Mater. Today Commun. 2021, 28, 102619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanakumar, K.; Wang, M.-H. Trichoderma Based Synthesis of Anti-Pathogenic Silver Nanoparticles and Their Characterization, Antioxidant and Cytotoxicity Properties. Microb. Pathog. 2018, 114, 269–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sonawane, H.; Arya, S.; Math, S.; Shelke, D. Myco-Synthesized Silver and Titanium Oxide Nanoparticles as Seed Priming Agents to Promote Seed Germination and Seedling Growth of Solanum lycopersicum: A Comparative Study. Int. Nano Lett. 2021, 11, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanakumar, K.; Shanmugam, S.; Varukattu, N.B.; MubarakAli, D.; Kathiresan, K.; Wang, M.-H. Biosynthesis and Characterization of Copper Oxide Nanoparticles from Indigenous Fungi and Its Effect of Photothermolysis on Human Lung Carcinoma. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2019, 190, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dorjee, L.; Kamil, D.; Kumar, R.; Khokhar, M.; Aggarwal, R.; Gogoi, R. Synthesis of Promising Copper Nanoparticles Utilizing Biocontrol Agents, Trichoderma virens and Chaetomium globosum. Indian J. Agric. Sci. 2024, 94, 061–067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulati, S.; Sachdeva, M.; Bhasin, K.K. Capping Agents in Nanoparticle Synthesis: Surfactant and Solvent System. AIP Conf. Proc. 2018, 1953, 030214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husseiny, S.M.; Salah, T.A.; Anter, H.A. Biosynthesis of Size Controlled Silver Nanoparticles by Fusarium oxysporum, Their Antibacterial and Antitumor Activities. Beni-Suef Univ. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2015, 4, 225–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahluwalia, V.; Kumar, J.; Sisodia, R.; Shakil, N.A.; Walia, S. Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles by Trichoderma harzianum and Their Bio-Efficacy Evaluation against Staphylococcus aureus and Klebsiella pneumonia. Ind. Crops Prod. 2014, 55, 202–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Narware, J.; Singh, S.P.; Manzar, N.; Kashyap, A.S. Biogenic Synthesis, Characterization, and Evaluation of Synthesized Nanoparticles against the Pathogenic Fungus Alternaria solani. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1159251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sundaravadivelan, C.; Padmanabhan, M.N. Effect of Mycosynthesized Silver Nanoparticles from Filtrate of Trichoderma harzianum against Larvae and Pupa of Dengue Vector Aedes aegypti L. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. Int. 2014, 21, 4624–4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arya, S.; Sonawane, H.; Math, S.; Tambade, P.; Chaskar, M.; Shinde, D. Biogenic Titanium Nanoparticles (TiO2NPs) from Tricoderma citrinoviride Extract: Synthesis, Characterization and Antibacterial Activity against Extremely Drug-Resistant Pseudomonas Aeruginosa. Int. Nano Lett. 2021, 11, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, M.K.Y.; Salem, S.S.; Abu-Elghait, M.; Azab, M.S. Biosynthesis of Silver and Gold Nanoparticles and Their Efficacy Towards Antibacterial, Antibiofilm, Cytotoxicity, and Antioxidant Activities. Appl. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2023, 195, 1158–1183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chinnaperumal, K.; Govindasamy, B.; Paramasivam, D.; Dilipkumar, A.; Dhayalan, A.; Vadivel, A.; Sengodan, K.; Pachiappan, P. Bio-Pesticidal Effects of Trichoderma viride Formulated Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticle and Their Physiological and Biochemical Changes on Helicoverpa armigera (Hub.). Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2018, 149, 26–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guilger, M.; Pasquoto-Stigliani, T.; Bilesky-Jose, N.; Grillo, R.; Abhilash, P.C.; Fraceto, L.F.; de Lima, R. Biogenic Silver Nanoparticles Based on Trichoderma harzianum: Synthesis, Characterization, Toxicity Evaluation and Biological Activity. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 44421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaki, S.A.; Ouf, S.A.; Albarakaty, F.M.; Habeb, M.M.; Aly, A.A.; Abd-Elsalam, K.A. Trichoderma harzianum-Mediated ZnO Nanoparticles: A Green Tool for Controlling Soil-Borne Pathogens in Cotton. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaki, S.A.; Ouf, S.A.; Abd-Elsalam, K.A.; Asran, A.A.; Hassan, M.M.; Kalia, A.; Albarakaty, F.M. Trichogenic Silver-Based Nanoparticles for Suppression of Fungi Involved in Damping-Off of Cotton Seedlings. Microorganisms 2022, 10, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- EL-Moslamy, S.H.; Yahia, I.S.; Zahran, H.Y.; Kamoun, E.A. Novel Biosynthesis of MnO NPs Using Mycoendophyte: Industrial Bioprocessing Strategies and Scaling-up Production with Its Evaluation as Anti-Phytopathogenic Agents. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 2052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saravanakumar, K.; Sathiyaseelan, A.; Mariadoss, A.V.A.; Hu, X.; Venkatachalam, K.; Wang, M.-H. Nucleolin Targeted Delivery of Aptamer Tagged Trichoderma Derived Crude Protein Coated Gold Nanoparticles for Improved Cytotoxicity in Cancer Cells. Process Biochem. 2021, 102, 325–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilesky-José, N.; Maruyama, C.; Germano-Costa, T.; Campos, E.; Carvalho, L.; Grillo, R.; Fraceto, L.F.; De Lima, R. Biogenic α-Fe2O3 Nanoparticles Enhance the Biological Activity of Trichoderma against the Plant Pathogen Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. ACS Sustain. Chem. Eng. 2021, 9, 1669–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pasquoto-Stigliani, T.; Guilger-Casagrande, M.; Campos, E.V.R.; Germano-Costa, T.; Bilesky-José, N.; Migliorini, B.B.; Feitosa, L.O.; Sousa, B.T.; de Oliveira, H.C.; Fraceto, L.F.; et al. Titanium Biogenic Nanoparticles to Help the Growth of Trichoderma harzianum to Be Used in Biological Control. J. Nanobiotechnol. 2023, 21, 166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Gazzar, N.; Almanaa, T.N.; Reda, R.M.; El Gaafary, M.N.; Rashwan, A.A.; Mahsoub, F. Assessment the Using of Silica Nanoparticles (SiO2NPs) Biosynthesized from Rice Husks by Trichoderma harzianum MF780864 as Water Lead Adsorbent for Immune Status of Nile Tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus). Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 5119–5130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomah, A.A.; Alamer, I.S.A.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.-Z. Mycosynthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Screened Trichoderma Isolates and Their Antifungal Activity against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1955. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahanty, S.; Bakshi, M.; Ghosh, S.; Chatterjee, S.; Bhattacharyya, S.; Das, P.; Das, S.; Chaudhuri, P. Green Synthesis of Iron Oxide Nanoparticles Mediated by Filamentous Fungi Isolated from Sundarban Mangrove Ecosystem, India. BioNanoScience 2019, 9, 637–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bulgari, D.; Fiorini, L.; Gianoncelli, A.; Bertuzzi, M.; Gobbi, E. Enlightening Gliotoxin Biological System in Agriculturally Relevant Trichoderma Spp. Front. Microbiol. 2020, 11, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-P.; Ji, N.-Y. Chemistry and Biology of Marine-Derived Trichoderma Metabolites. Nat. Prod. Bioprospect. 2024, 14, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Herrera Pérez, G.M.; Castellano, L.E.; Ramírez Valdespino, C.A. Trichoderma and Mycosynthesis of Metal Nanoparticles: Role of Their Secondary Metabolites. J. Fungi 2024, 10, 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof10070443

Herrera Pérez GM, Castellano LE, Ramírez Valdespino CA. Trichoderma and Mycosynthesis of Metal Nanoparticles: Role of Their Secondary Metabolites. Journal of Fungi. 2024; 10(7):443. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof10070443

Chicago/Turabian StyleHerrera Pérez, Guillermo M., Laura E. Castellano, and Claudia A. Ramírez Valdespino. 2024. "Trichoderma and Mycosynthesis of Metal Nanoparticles: Role of Their Secondary Metabolites" Journal of Fungi 10, no. 7: 443. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof10070443