Strategies to Reduce Mortality in Adult and Neonatal Candidemia in Developing Countries

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Differences in Epidemiology of Candidemia between Developed and Developing Countries

Neonatal Candidemia

3. Challenges in Diagnosis of Candidemia in Developing Countries

4. Challenges in Management of Candidemia in Developing Countries

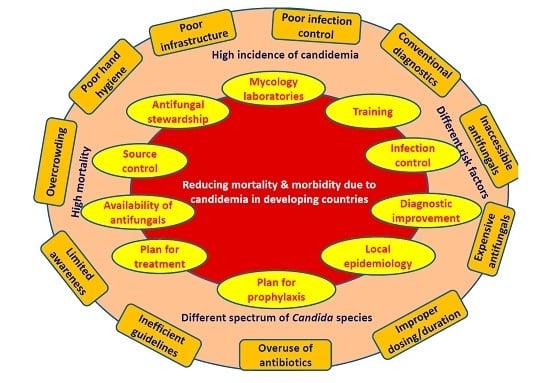

5. Strategies to Reduce Mortality and Morbidity Due to Candidemia in Developing Countries

- Development of reference laboratory and improvement of mycology laboratories: Small countries require at least one reference laboratory and multiple in large countries. Establishment of more numbers of laboratories is essential to cater to large populations in developing countries. The government is required to spend more money to meet those essential needs.

- Improvement in diagnosis: Although the resources in developing countries are limited, reasonable alternatives may be implemented. Firstly, maintaining a high level of suspicion particularly in high risk patients may expedite the investigation process. Secondly, better sample collection will improve diagnosis. Thirdly, the identification of positive cultures may be accelerated by collaboration among multiple centers of a region pooling fund for purchase of a MALDI-TOF whose running cost after initial installation is very low and affordable for developing countries. Fourthly, although specific fungal serological markers are expensive, cheaper alternatives like PCT and CRP, which have shown a high negative predictive value may be standardized and validated for excluding candidemia. Fifthly, standardization of Candida PCR may prove cost effective in the long run for early diagnosis. Sixthly, a good communication between mycology laboratory and clinicians and critical call alert would help in early antifungal therapy. Emergency laboratories should function around the clock and should be equipped with automated blood culture systems. The results should be communicated to the clinician in a real-time fashion.

- Education: The importance of diagnosis of candidemia must be included in the curriculum of residents and health care workers. Simple educational programs including lectures, posters, hands on training and self-study modules for physicians and nursing staff will lead to a significant decrease in catheter line-associated blood stream infection (CLABSI) rates. Educational programs along with periodic reassessment of health care worker knowledge regarding infection-prevention practices are necessary for compliance to evidence-based practices.

- Improvement of infection control: Training in infection control is of paramount importance. Hands of health care workers are the frequent source and transmitters of Candida from patient to patient and environment to patient [105]. Adequate maintenance of hand hygiene reduces rates of nosocomial infections and cross-transmission as shown in many studies over the last few decades [106]. Improving hand hygiene and optimal catheter placement help to reduce sepsis episodes. A significant reduction (16.9% to 9.9%) in nosocomial infections was noticed after a hand hygiene promotion program over a period of four years in a developed country [107]. Hand hygiene also reduced CLABSI rate by 72% in patients receiving parenteral nutrition [108]. The use of World Health Organization (WHO)-advocated alcohol-based hand rubs is a practical solution to overcome the problems of hand hygiene in developing countries. Audits are required to estimate the compliance and reason of non-compliance of infection control practices.

- Source control: Source control is implemented to control a focus of infection and reduce the favorable conditions that promote microorganism growth or that maintain the impairment of host defenses [109]. The removal of any pre-existing central vein catheters or abscesses or other fluid collections will help to reduce mortality due to candidemia [88]. It is recommended to remove the central venous catheters (CVCs) as early as possible in candidemia in non-neutropenic patients when the source is presumed to be the CVC [80]. In the neutropenic patient, the decision of removing CVC is individualized, as the source of Candida in this group is generally other than a CVC (e.g., gastrointestinal tract) [80]. Many studies have shown the effect of both timing of therapy and/or source control on mortality. Early initiation of appropriate antifungal therapy and removal of CVC or drainage of infected material are associated with better overall outcomes [57,88,110,111,112,113]. Moreover, mortality in candidemia patients with septic shock reaches 100% if an antifungal is not begun within 24 h and the source is not controlled [80]. Giuliano et al. demonstrated the use of topical prophylaxis with nystatin and adequate CVC management in neurosurgical ICU to prevent IC [114]. Lagunes et al. (Spain) conducted a retrospective, multi-center, cohort study in surgical wards and ICUs and reported adequate source control in 60% of patients with intra-abdominal candidiasis (IAC) within 48 h of diagnosis [109]. They identified inadequate source control as the only common risk factor for 30-day mortality in both ICU and non-ICU groups. Better survival was observed in patients receiving both proper source control and antifungal therapy.

- Local epidemiology: A wide range of variation is observed in Candida species distribution between developing countries, even within the countries [95,115,116]. While the culture/susceptibility data are yet to be released by laboratories, the treatment decisions are based on the knowledge of local epidemiology (frequency of isolation and antifungal susceptibility of each Candida species) [80]. Moreover, real time data generation on antifungal susceptibility is a challenge in most of the centers of developing countries. The information maintained by the microbiology laboratory may be circulated regularly to clinicians and antifungal stewardship teams for therapeutic decisions. It will also help in planning local candidemia management strategies. Many regions in United States, Europe and few developing countries conduct both sentinel and population based surveys over many years and keep records. The 2011 WHO rapid advice guidelines for appropriate antifungal regimens may be incorporated into country-specific or region-specific treatment guidelines [117].

- Prophylaxis: Antifungal prophylaxis in high-risk adults and premature low birth weight neonates is an important strategy aiming at reduction of mortality due to candidemia. Although few studies have shown effectiveness of echinocandin prophylaxis in transplant patients, fluconazole, which is a cheaper alternative, is also beneficial and affordable in developing countries. Weekly fluconazole prophylaxis instead of daily dosing may be cost-effective for haematological or neutropenic patients to decrease morbidity and mortality due to candidemia [118]. However, prophylaxis in adult ICUs (overall rate of IC <5%) is recommended only in selected patient groups [80,119]. A meta-analysis by Cruciani et al. demonstrated a decrease in rate of candidemia (relative risk 0.3), attributable mortality rate (RR 0.25) and an overall mortality rate (RR 0.6) by fluconazole prophylaxis, thereby strengthening the use of fluconazole as a cheap alternative for developing countries [120]. However, the risk benefit ratio is required to be optimized while giving fluconazole prophylaxis especially after emergence of C. auris in many developing countries and the rise of fluconazole-resistant Candida species infection rate.

- 8.

- Treatment: Appropriate early management of IC is required to reduce hospital or ICU stay, thereby decreasing the eventual cost of hospitalization and management, and finally reducing mortality due to candidemia. It is generally believed that the early institution of antifungal therapy (fluconazole/echinocandins) within 12–72 h of positive culture prevents mortality (1.5–2 times patients survive) in adults in ICU [110,111,126]. On the contrary, few studies did not find any role of early antifungal therapy in decreasing mortality [127]. It had been shown that high mortality still occurs even when the antifungal is initiated in a timely manner [112]. Lopez-Corter et al. observed no higher mortality in a multi-center study when empiric or target therapy included fluconazole in place of echinocandins, supporting the use of fluconazole safely in developing countries [128]. They even denied the preference of echinocandins in severely ill patients. The antifungal susceptibility data of the developing countries can guide the use of fluconazole as effective antifungals in susceptible isolates. Additionally, amphotericin B deoxycholate can be used as a cost-effective alternative especially in neonates.

- 9.

- Availability of antifungal drugs: A big barrier is faced by low-income and middle-income countries to access antifungal agents, and the drug cost [117]. In many developing countries, medicine regulatory authorities are compromised by insufficient resources and human capacity. Drug companies should consider low pricing for developing countries, which may be ensured by providing incentives to pharmaceutical manufacturers for producing generic versions of the drugs. Currently, amphotericin B is not available in 42 developing countries and lacks license in 22 countries. In the process, around 6.6% of the global population do not have access to amphotericin B [129].

- 10.

- Antifungal stewardship: The rational use of antifungal agents in health care institutions must be followed for monitoring and guiding the appropriate antifungal use including dosing, duration of therapy, and route of administration [130]. The aim of this program is to achieve the best outcome without unnecessary adverse reactions and emergence of drug resistance [54]. Apisarnthanarak et al. from Thailand have shown the success of a program comprising of education, antifungal hepatic and/or renal dose adjustment chart, specific prescription forms for antifungal drugs and prescription-control approach [130,131]. They noticed a 59% reduction in antifungal prescriptions, a significant decrease in inappropriate antifungal use (71% to 24%), continuous overall reduction in antifungal use and significantly lower fluconazole use. For the success of the program, an efficient teamwork and adequate hygiene and standard precautions are necessary which must be monitored regularly by infection control nurses. However, the programs in developing countries generally depend on individual efforts of infectious disease physicians rather than teamwork [132].

6. Strategies Specific for Neonates

- Antifungal prophylaxis: Antifungal prophylaxis as discussed previously is most beneficial for preterm infants <1000 grams and/or ≤28 weeks’ gestation from birth until they no longer require central/peripheral access.

- Maternal vaginal candidiasis screening and decolonization: Preterm infants are colonized by Candida from maternal flora [133]. Studies from developing countries have reported a prevalence of vaginal candidiasis ranging from 14.6% to 42.9% in pregnant females [134,135]. Screening and management of maternal vaginal colonization and candidiasis may help prevent neonatal colonization at an early stage. Even empiric therapy for antepartum women has been suggested [34].

- Neonatal medication restriction: The use of broad-spectrum antibiotics, especially third and fourth generation cephalosporins and carbapenems, acid inhibitors and steroids in preterm babies is linked to an increased risk of Candida infection [133]. The usage of an aminoglycoside instead of cephalosporin or carbapenem as an empiric therapy may reduce the risk of IC. Moderate evidence exists for restricting the use of H2 blockers and PPI in gastritis. Similarly, the use of dexamethasone in intubated infants is associated with increased risks of IC and candidemia (10%), respectively [133].

- Early breastfeeding and enteral feeding: Necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC) is reported to be associated with high rates of fungal infections (16.5%) [133]. The early establishment of breastfeeding within 3 days of life has shown decreased rates of fungal infections in infants of <1000 g due to development of a favorable microflora in the neonate. Early enteral feeding also promotes the development of healthy gut microflora [34]. The studies regarding the effect of risk factor reduction need to be evaluated in neonates in developing countries.

- Lactoferrin and probiotic administration: Bovine lactoferrin alone or in combination with probiotics given to <1500 g of neonates in an RCT showed a decreased incidence of late onset sepsis although the sample size of the trial was small [34]. Clinical trials conducted in preterm neonates demonstrated a favorable effect of Saccharomyces boulardii containing probiotics without any evidence of fungemia or sepsis [136]. However, few studies reported occasional cases of fungemia subsequent to the use of probiotics, questioning the safety of these products [136,137,138,139,140]. It is therefore recommended to use probiotics cautiously in pre-term neonates and immunocompromised patients [139].

- Heightened infection control: Chen et al. reported implementation of aggressive hand hygiene practices in addition to fluconazole prophylaxis to be more successful in preventing candidemia in preterm infants of <33 weeks in NICU than prophylaxis alone [13]. Chitnis et al. further demonstrated a significant reduction (75%) in the overall incidence of candidemia in NICUs due to improved central line insertion and maintenance practices over a period of 10 years [141]. These data suggest the successful contribution of heightened infection control in NICUs.

7. Future Perspectives

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pappas, P.G. Invasive Candidiasis. Infect. Dis. Clin. N. Am. 2006, 20, 485–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gudlaugsson, O.; Gillespie, S.; Lee, K.; Berg, J.V.; Hu, J.; Messer, S.; Herwaldt, L.; Pfaller, M.; Diekema, D. Attributable Mortality of Nosocomial Candidemia, Revisited. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2003, 37, 1172–1177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barchiesi, F.; Orsetti, E.; Gesuita, R.; Skrami, E.; Manso, E. Epidemiology, clinical characteristics, and outcome of candidemia in a tertiary referral center in Italy from 2010 to 2014. Infection 2016, 44, 205–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Raka, L. Lowbury Lecture 2008: Infection control and limited resources—Searching for the best solutions. J. Hosp. Infect. 2009, 72, 292–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittet, D.; Donaldson, L. Challenging the world: Patient safety and health care-associated infection. Int. J. Qual. Heal. Care 2006, 18, 4–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittet, D.; Allegranzi, B.; Storr, J.; Nejad, S.B.; Dziekan, G.; Leotsakos, A.; Donaldson, L. Infection control as a major World Health Organization priority for developing countries. J. Hosp. Infect. 2008, 68, 285–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathur, P. Hand hygiene: Back to the basics of infection control. Indian J. Med. Res. 2011, 134, 611–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Diekema, D.J. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis: A persistent public health problem. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2007, 20, 133–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yapar, N. Epidemiology and risk factors for invasive candidiasis. Ther. Clin. Risk Manag. 2014, 10, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campion, E.W.; Kullberg, B.J.; Arendrup, M.C. Invasive Candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2015, 373, 1445–1456. [Google Scholar] [Green Version]

- Zaoutis, T. Candidemia in children. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2010, 26, 1761–1768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaoutis, T.E.; Prasad, P.A.; Localio, A.R.; Coffin, S.E.; Bell, L.M.; Walsh, T.J.; Gross, R. Risk Factors and Predictors for Candidemia in Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Patients: Implications for Prevention. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2010, 51, e38–e45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chapman, B.; Slavin, M.; Marriott, D.; Halliday, C.; Kidd, S.; Arthur, I.; Bak, N.; Heath, C.H.; Kennedy, K.; Morrissey, C.O.; et al. Changing epidemiology of candidaemia in Australia. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 1103–1108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, J.-L.; Rello, J.; Marshall, J.; Silva, E.; Anzueto, A.; Martin, C.D.; Moreno, R.; Lipman, J.; Gomersall, C.; Sakr, Y.; et al. International study of the prevalence and outcomes of infection in intensive care units. JAMA 2009, 302, 2323–2329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Asmundsdottir, L.R.; Erlendsdottir, H.; Gottfredsson, M. Nationwide study of candidemia, antifungal use, and antifungal drug resistance in Iceland, 2000 to 2011. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 841–848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, A. Fungal Infections in Asia: The Eastern Frontier of Mycology, 1st ed.; Elsevier: Gurgaon, India, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tan, B.H.; Chakrabarti, A.; Li, R.Y.; Patel, A.K.; Watcharananan, S.P.; Liu, Z.; Chindamporn, A.; Tan, A.L.; Sun, P.L.; Wu, U.I.; et al. Incidence and species distribution of candidaemia in Asia: A laboratory-based surveillance study. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 946–953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Z.-T.; Wu, L.; Liu, X.-Y.; Zhou, M.; Li, J.; Wu, J.-Y.; Cai, Y.; Mao, E.-Q.; Chen, E.-Z.; Lortholary, O. Epidemiology, species distribution and outcome of nosocomial Candida spp. bloodstream infection in Shanghai. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.; Liu, N.; Yin, M.; Han, H.; Yue, J.; Zhang, F.; Shan, T.; Guo, H.; Wu, D. The epidemiology, antifungal use and risk factors of death in elderly patients with candidemia: A multicentre retrospective study. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trouvé, C.; Blot, S.; Hayette, M.P.; Jonckheere, S.; Patteet, S.; Rodriguez-Villalobos, H.; Symoens, F.; Van Wijngaerden, E.; Lagrou, K. Epidemiology and reporting of candidaemia in Belgium: A multi-centre study. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 649–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ulu Kilic, A.; Alp, E.; Cevahir, F.; Ture, Z.; Yozgat, N. Epidemiology and cost implications of candidemia, a 6-year analysis from a developing country. Mycoses 2017, 60, 198–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tadec, L.; Talarmin, J.P.; Gastinne, T.; Bretonnière, C.; Miegeville, M.; Le Pape, P.; Morio, F. Epidemiology, risk factor, species distribution, antifungal resistance and outcome of Candidemia at a single French hospital: A 7-year study. Mycoses 2016, 59, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kreusch, A.; Karstaedt, A.S. Candidemia among adults in Soweto, South Africa, 1990–2007. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 17, e621–e623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez, L.; Bustamante, B.; Huaroto, L.; Agurto, C.; Illescas, R.; Ramirez, R.; Diaz, A.; Hidalgo, J. A multi-centric Study of Candida bloodstream infection in Lima-Callao, Peru: Species distribution, antifungal resistance and clinical outcomes. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ellis, M.; Hedstrom, U.; Jumaa, P.; Bener, A. Epidemiology, presentation, management and outcome of candidemia in a tertiary care teaching hospital in the United Arab Emirates, 1995–2001. Med. Mycol. 2003, 41, 521–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chakrabarti, A. Incidence, characteristics and outcome of ICU-acquired candidemia in India. Intensive Care Med. 2015, 41, 285–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yapar, N.; Pullukcu, H.; Avkan-Oguz, V.; Sayin-Kutlu, S.; Ertugrul, B.; Sacar, S.; Cetin, B.; Kaya, O. Evaluation of species distribution and risk factors of candidemia: A multicenter case-control study. Med. Mycol. 2011, 49, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yingfang, Y.; Lizhong, D.; Tianming, Y.; Jiyan, Z.; An, C.; Lihua, C.; Liping, S. Risk Factors and Clinical Analysis for Invasive Fungal Infection in Neonatal Intensive Care Unit Patients. Am. J. Perinatol. 2013, 30, 589–593. [Google Scholar]

- Ding, X.; Yan, D.; Sun, W.; Zeng, Z.; Su, R.; Su, J. Epidemiology and risk factors for nosocomial Non-Candida albicans candidemia in adult patients at a tertiary care hospital in North China. Med. Mycol. 2015, 53, 684–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, M.; Huang, S.; Guo, L.; Li, H.; Wang, F.; Zhang, Q.; Song, G. Clinical features and risk factors for blood stream infections of Candida in neonates. Exp. Ther. Med. 2015, 10, 1139–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wenzel, R.P.; Gennings, C. Bloodstream infections due to Candida species in the intensive care unit: Identifying especially high-risk patients to determine prevention strategies. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2005, 41, S389–S393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gibbs, K.A.; Kleinman, L.C.; Jenkins, S.G.; Herold, B.C.; Holzman, I.R. The vulnerable very low birth weight infant: Late onset bloodstream infections. Pediatrics 2010, 3, 117–125. [Google Scholar]

- Benjamin, D.K.; DeLong, E.; Cotten, C.M.; Garges, H.P.; Steinbach, W.J.; Clark, R.H. Mortality following blood culture in premature infants: Increased with Gram-negative bacteremia and candidemia, but not Gram-positive bacteremia. J. Perinatol. 2004, 24, 175–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shane, A.; Stoll, B. Recent Developments and Current Issues in the Epidemiology, Diagnosis, and Management of Bacterial and Fungal Neonatal Sepsis. Am. J. Perinatol. 2013, 30, 131–142. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Hirano, R.; Sakamoto, Y.; Kudo, K.; Ohnishi, M. Retrospective analysis of mortality and Candida isolates of 75 patients with candidemia: A single hospital experience. Infect. Drug Resist. 2015, 8, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Puig-Asensio, M.; Pemán, J.; Zaragoza, R.; Garnacho-Montero, J.; Martín-Mazuelos, E.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Almirante, B. Impact of Therapeutic Strategies on the Prognosis of Candidemia in the ICU*. Crit. Care Med. 2014, 42, 1423–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Juyal, D.; Sharma, M.; Pal, S.; Rathaur, V.K.; Sharma, N. Emergence of non-albicans Candida species in neonatal candidemia. N. Am. J. Med. Sci. 2013, 5, 541–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agarwal, J.; Bansal, S.; Malik, G.K.; Jain, A. Trends in neonatal septicemia: Emergence of non-albicans Candida. Indian Pediatr. 2004, 41, 712–715. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Goel, N.; Ranjan, P.; Aggarwal, R.; Chaudhary, U.; Sanjeev, N. Emergence of Nonalbicans Candida in neonatal septicemia and antifungal susceptibility: Experience from a tertiary care center. J. Lab. Physicians 2009, 1, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrivastava, G.; Bajpai, T.; Bhatambare, G.; Chitnis, V.; Deshmukh, A. Neonatal candidemia: Clinical importance of species identification. Int. Med. J. Sifa Univ. 2015, 2, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ariff, S.; Saleem, A.F.; Soofi, S.B.; Sajjad, R. Clinical spectrum and outcomes of neonatal candidiasis in a tertiary care hospital in Karachi, Pakistan. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2011, 5, 216–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammoud, M.S.; Al-Taiar, A.; Fouad, M.; Raina, A.; Khan, Z. Persistent candidemia in neonatal care units: Risk factors and clinical significance. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2013, 17, e624–e628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Hal, S.J.; Marriott, D.J.E.; Chen, S.C.A.; Nguyen, Q.; Sorrell, T.C.; Ellis, D.H.; Slavin, M.A. Candidemia following solid organ transplantation in the era of antifungal prophylaxis: The Australian experience. Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2009, 11, 122–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doi, A.M.; Pignatari, A.C.C.; Edmond, M.B.; Marra, A.R.; Camargo, L.F.A.; Siqueira, R.A.; da Mota, V.P.; Colombo, A.L. Epidemiology and Microbiologic Characterization of Nosocomial Candidemia from a Brazilian National Surveillance Program. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0146909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andes, D.R.; Safdar, N.; Baddley, J.W.; Alexander, B.; Brumble, L.; Freifeld, A.; Hadley, S.; Herwaldt, L.; Kauffman, C.; Lyon, G.M.; et al. The epidemiology and outcomes of invasive Candida infections among organ transplant recipients in the United States: Results of the Transplant-Associated Infection Surveillance Network (TRANSNET). Transpl. Infect. Dis. 2016, 18, 921–931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Richardson, M.; Lass-Flörl, C. Changing epidemiology of systemic fungal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2008, 14, 5–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Moet, G.J.; Messer, S.A.; Jones, R.N.; Castanheira, M. Geographic variations in species distribution and echinocandin and azole antifungal resistance rates among Candida bloodstream infection isolates: Report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2008 to 2009). J. Clin. Microbiol. 2011, 49, 396–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinbach, W.J.; Roilides, E.; Berman, D.; Hoffman, J.A.; Groll, A.H.; Bin-Hussain, I.; Palazzi, D.L.; Castagnola, E.; Halasa, N.; Velegraki, A.; et al. Results From a Prospective, International, Epidemiologic Study of Invasive Candidiasis in Children and Neonates. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. J. 2012, 31, 1252–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Messer, S.A.; Jones, R.N.; Fritsche, T.R. International surveillance of Candida spp. and Aspergillus spp.: Report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2003). J. Clin. Microbiol. 2006, 44, 1782–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nucci, M.; Thompson-Moya, L.; Guzman-Blanco, M.; Tiraboschi, I.N.; Cortes, J.A.; Echevarría, J.; Sifuentes, J.; Zurita, J.; Santolaya, M.E.; Alvarado Matute, T.; et al. Recommendations for the management of candidemia in adults in Latin America. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2013, 30, 179–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rudramurthy, S.M.; Chakrabarti, A.; Paul, R.A.; Sood, P.; Kaur, H.; Capoor, M.R.; Kindo, A.J.; Marak, R.S.K.; Arora, A.; Sardana, R.; et al. Candida auris candidaemia in Indian ICUs: Analysis of risk factors. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2017, 72, 1794–1801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bassetti, M.; Trecarichi, E.M.; Righi, E.; Sanguinetti, M.; Bisio, F.; Posteraro, B.; Soro, O.; Cauda, R.; Viscoli, C.; Tumbarello, M. Incidence, risk factors, and predictors of outcome of candidemia. Survey in 2 Italian university hospitals. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2007, 58, 325–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arendrup, M.C. Epidemiology of invasive candidiasis. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2010, 16, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Castanheira, M. Nosocomial candidiasis: Antifungal stewardship and the importance of rapid diagnosis. Med. Mycol. 2016, 54, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouza, E.; Muñoz, P. Epidemiology of candidemia in intensive care units. Int. J. Antimicrob. Agents 2008, 32, S87–S91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, J.K.; Golan, Y.; Ruthazer, R.; Karchmer, A.W.; Carmeli, Y.; Lichtenberg, D.; Chawla, V.; Young, J.; Hadley, S. Factors associated with candidemia caused by non-albicans Candida species versus Candida albicans in the intensive care unit. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2008, 46, 1206–1213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Kullberg, B.J.; Bow, E.J.; Hadley, S.; León, C.; Nucci, M.; Patterson, T.F.; Perfect, J.R. Early treatment of candidemia in adults: A review. Med. Mycol. 2011, 49, 113–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimopoulos, G.; Ntziora, F.; Rachiotis, G.; Armaganidis, A.; Falagas, M.E. Candida albicans versus non-albicans intensive care unit-acquired bloodstream infections: Differences in risk factors and outcome. Anesth. Analg. 2008, 106, 523–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burwell, L.A.; Kaufman, D.; Blakely, J.; Stoll, B.J.; Fridkin, S.K. Antifungal prophylaxis to prevent neonatal candidiasis: A survey of perinatal physician practices. Pediatrics 2006, 118, e1019–e1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gopichand, W.R.; Madhusudan, B.V. Study of clinical spectrum and risk factors of neonatal candidemia. Indian J. Pathol. Microbiol. 2015, 58, 472–474. [Google Scholar]

- Shane, A.L.; Stoll, B.J. Neonatal sepsis: Progress towards improved outcomes. J. Infect. 2014, 68, S24–S32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, K.; Chakrabarti, A.; Narang, A.; Gopalan, S. Yeast colonisation and fungaemia in preterm neonates in a tertiary care centre. Indian J. Med. Res. 1999, 110, 169–173. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, D.A. Challenging issues in neonatal candidiasis. Curr. Med. Res. Opin. 2010, 26, 1769–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lovero, G.; De Giglio, O.; Montagna, O.; Diella, G.; Divenuto, F.; Lopuzzo, M.; Rutigliano, S.; Laforgia, N.; Caggiano, G.; Montagna, M.T. Epidemiology of candidemia in neonatal intensive care units: A persistent public health problem. Ann. Ig 2016, 28, 282–287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Fu, J.; Wang, X.; Wei, B.; Jiang, Y.; Chen, J. Risk factors and clinical analysis of candidemia in very-low-birth-weight neonates. Am. J. Infect. Control 2016, 44, 1321–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sherlock, R. Neonatal sepsis and septic shock: Current trends in epidemiology and management. J. Pediatr. Infect. Dis. 2009, 4, 153–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benjamin, D.K.; Stoll, B.J.; Gantz, M.G.; Walsh, M.C.; Sánchez, P.J.; Das, A.; Shankaran, S.; Higgins, R.D.; Auten, K.J.; Miller, N.A.; et al. Neonatal candidiasis: Epidemiology, risk factors, and clinical judgment. Pediatrics 2010, 126, e865–e873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cetinkaya, M.; Ercan, T.; Saglam, O.; Buyukkale, G.; Kavuncuoglu, S.; Mete, F. Efficacy of Prophylactic Fluconazole Therapy in Decreasing the Incidence of Candida Infections in Extremely Low Birth Weight Preterm Infants. Am. J. Perinatol. 2014, 31, 1043–1048. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Parikh, T.B.; Patankar, C.V.N.; Rao, S.; Bisure, K.; Udani, R.H.; Mehta, P. Fluconazole prophylaxis against fungal colonization and invasive fungal infection in very low birth weight infants. Indian Pediatr. 2007, 44, 830–837. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Wolk, D.M.; Lowery, T.J. T2MR and T2Candida: Novel technology for the rapid diagnosis of candidemia and invasive candidiasis. Future Microbiol. 2016, 11, 103–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitale, R.G.; Nucci, M. Diagnosis of Candidemia. Curr. Fungal Infect. Rep. 2014, 8, 90–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arvanitis, M.; Anagnostou, T.; Fuchs, B.B.; Caliendo, A.M.; Mylonakis, E. Molecular and nonmolecular diagnostic methods for invasive fungal infections. Clin. Microbiol. Rev. 2014, 27, 490–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clancy, C.J.; Nguyen, M.H. Finding the missing 50% of invasive candidiasis: How nonculture diagnostics will improve understanding of disease spectrum and transform patient care. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013, 56, 1284–1292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beyda, N.D.; Alam, M.J.; Garey, K.W. Comparison of the T2Dx instrument with T2Candida assay and automated blood culture in the detection of Candida species using seeded blood samples. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2013, 77, 324–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mylonakis, E.; Clancy, C.J.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Garey, K.W.; Alangaden, G.J.; Vazquez, J.A.; Groeger, J.S.; Judson, M.A.; Vinagre, Y.M.; Heard, S.O.; et al. T2 magnetic resonance assay for the rapid diagnosis of candidemia in whole blood: A clinical trial. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, 892–899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghosh, A.K.; Paul, S.; Sood, P.; Rudramurthy, S.M.; Rajbanshi, A.; Jillwin, T.J.; Chakrabarti, A. Matrix-assisted laser desorption ionization time-of-flight mass spectrometry for the rapid identification of yeasts causing bloodstream infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2015, 21, 372–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zoll, J.; Snelders, E.; Verweij, P.E.; Melchers, W.J.G. Next-Generation Sequencing in the Mycology Lab. Curr. Fungal Infect. Rep. 2016, 10, 37–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berzaghi, R.; Colombo, A.L.; de Oliveira Machado, A.M.; de Camargo, Z.P. New approach for diagnosis of candidemia based on detection of a 65-kilodalton antigen. Clin. Vaccine Immunol. 2009, 16, 1538–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Theel, E.S.; Doern, C.D. β-D-Glucan testing is important for diagnosis of invasive fungal infections. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2013, 51, 3478–3483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.R.; Clancy, C.J.; Marr, K.A.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Reboli, A.C.; Schuster, M.G.; Vazquez, J.A.; Walsh, T.J.; et al. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 62, e1–e50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pappas, P.G.; Kauffman, C.A.; Andes, D.; Benjamin, D.K., Jr.; Calandra, T.F.; Edwards, J.E., Jr.; Filler, S.G.; Fisher, J.F.; Kullberg, B.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Management of Candidiasis: 2009 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 503–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaijakul, S.; Vazquez, J.A.; Swanson, R.N.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L. (1,3)-β-D-glucan as a prognostic marker of treatment response in invasive candidiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 55, 521–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- León, C.; Ostrosky-Zeichner, L.; Schuster, M. What’s new in the clinical and diagnostic management of invasive candidiasis in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2014, 40, 808–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Pascale, G.; Tumbarello, M. Fungal infections in the ICU- advances in treatment and diagnosis. Curr. Opin. Crit. Care 2015, 21, 421–429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martini, A.; Gottin, L.; Menestrina, N.; Schweiger, V.; Simion, D.; Vincent, J.L. Procalcitonin levels in surgical patients at risk of candidemia. J. Infect. 2010, 60, 425–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Charles, P.E.; Kus, E.; AHO, S.; Prin, S.; Doise, J.-M.; Olsson, N.-O.; Blettery, B.; Quenot, J.-P. Serum procalcitonin for the early recognition of nosocomial infection in the critically ill patients: A preliminary report. BMC Infect. Dis. 2009, 9, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; Chen, J.; Cai, B.; Zhang, J.; Li, L.; Liu, C.; Kang, Y.; Wang, L. The use of PCT, CRP, IL-6 and SAA in critically ill patients for an early distinction between candidemia and Gram positive/negative bacteremia. J. Infect. 2012, 64, 438–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kollef, M.; Micek, S.; Hampton, N.; Doherty, J.A.; Kumar, A. Septic shock attributed to Candida infection: Importance of empiric therapy and source control. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 1739–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kratzer, C.; Graninger, W.; Lassnigg, A.; Presterl, E. Design and use of Candida scores at the intensive care unit. Mycoses 2011, 54, 467–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Betts, R.F.; Nucci, M.; Talwar, D.; Gareca, M.; Queiroz-Telles, F.; Bedimo, R.J.; Herbrecht, R.; Ruiz-Palacios, G.; Young, J.H.; Baddley, J.W.; et al. A Multicenter, Double-Blind Trial of a High-Dose Caspofungin Treatment Regimen versus a Standard Caspofungin Treatment Regimen for Adult Patients with Invasive Candidiasis. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 48, 1676–1684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reboli, A.C.; Shorr, A.F.; Rotstein, C.; Pappas, P.G.; Kett, D.H.; Schlamm, H.T.; Reisman, A.L.; Biswas, P.; Walsh, T.J. Anidulafungin compared with fluconazole for treatment of candidemia and other forms of invasive candidiasis caused by Candida albicans: A multivariate analysis of factors associated with improved outcome. BMC Infect. Dis. 2011, 11, 261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reboli, A.C.; Rotstein, C.; Pappas, P.G.; Chapman, S.W.; Kett, D.H.; Kumar, D.; Betts, R.; Wible, M.; Goldstein, B.P.; Schranz, J.; et al. Anidulafungin versus Fluconazole for Invasive Candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 2472–2482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuse, E.R.; Chetchotisakd, P.; da Cunha, C.A.; Ruhnke, M.; Barrios, C.; Raghunadharao, D.; Sekhon, J.S.; Freire, A.; Ramasubramanian, V.; Demeyer, I.; et al. Micafungin versus liposomal amphotericin B for candidaemia and invasive candidosis: A phase III randomised double-blind trial. Lancet 2007, 369, 1519–1527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Duarte, J.; Betts, R.; Rotstein, C.; Colombo, A.L.; Thompson-Moya, L.; Smietana, J.; Lupinacci, R.; Sable, C.; et al. Comparision of Caspofungin and amphotericin B for Invasive Candidiasis. N. Engl. J. Med. 2002, 347, 2020–2029. [Google Scholar]

- Pfaller, M.A.; Castanheira, M.; Messer, S.A.; Moet, G.J.; Jones, R.N. Variation in Candida spp. distribution and antifungal resistance rates among bloodstream infection isolates by patient age: Report from the SENTRY Antimicrobial Surveillance Program (2008–2009). Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2010, 68, 278–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hong, Y.; Shaw, P.J.; Nath, C.E.; Yadav, S.P.; Stephen, K.R.; Earl, J.W.; McLachlan, A.J. Population Pharmacokinetics of Liposomal Amphotericin B in Pediatric Patients with Malignant Diseases. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2006, 50, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baley, J.E.; Meyers, C.; Kliegman, R.M.; Jacobs, M.R.; Blumer, J.L. Pharmacokinetics, outcome of treatment, and toxic effects of amphotericin B and 5-fluorocytosine in neonates. J. Pediatr. 1990, 116, 791–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wade, K.C.; Wu, D.; Kaufman, D.A.; Ward, R.M.; Benjamin, D.K.; Sullivan, J.E.; Ramey, N.; Jayaraman, B.; Hoppu, K.; Adamson, P.C.; et al. Population pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in young infants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2008, 52, 4043–4049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saxen, H.; Hoppu, K.; Pohjavuori, M. Pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in very low birth weight infants during the first two weeks of life. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1993, 54, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, J.W.; Seibel, N.L.; Amantea, M.; Whitcomb, P.; Pizzo, P.A.; Walsh, T.J. Safety and pharmacokinetics of fluconazole in children with neoplastic diseases. J. Pediatr. 1992, 120, 987–993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hope, W.W.; Smith, P.B.; Arrieta, A.; Buell, D.N.; Roy, M.; Kaibara, A.; Walsh, T.J.; Cohen-Wolkowiez, M.; Benjamin, D.K. Population pharmacokinetics of micafungin in neonates and young infants. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2010, 54, 2633–2637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santolaya, M.E.; Alvarado Matute, T.; de Queiroz Telles, F.; Colombo, A.L.; Zurita, J.; Tiraboschi, I.N.; Cortes, J.A.; Thompson-Moya, L.; Guzman-Blanco, M.; Sifuentes, J.; et al. Recommendations for the management of candidemia in neonates in Latin America. Latin America Invasive Mycosis Network. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2013, 30, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, L.; Wang, H.; Xiao, M.; Kudinha, T.; Mao, L.L.; Zhao, H.R.; Kong, F.; Xu, Y.C. The widely used ATB FUNGUS 3 automated readings in China and its misleading high MICs of Candida spp. to azoles: Challenges for developing countries’ clinical microbiology labs. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santolaya, M.E.; de Queiroz Telles, F.; Alvarado Matute, T.; Colombo, A.L.; Zurita, J.; Tiraboschi, I.N.; Cortes, J.A.; Thompson-Moya, L.; Guzman-Blanco, M.; Sifuentes, J.; et al. Recommendations for the management of candidemia in children in Latin America. Rev. Iberoam. Micol. 2013, 30, 171–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittet, D.; Allegranzi, B.; Sax, H.; Dharan, S.; Pessoa-Silva, C.L.; Donaldson, L.; Boyce, J.M. Evidence-based model for hand transmission during patient care and the role of improved practices. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2006, 6, 641–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allegranzi, B.; Pittet, D. Role of hand hygiene in healthcare-associated infection prevention. J. Hosp. Infect. 2009, 73, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pittet, D.; Hugonnet, S.; Harbarth, S.; Mourouga, P.; Sauvan, V.; Touveneau, S.; Perneger, T. V Effectiveness of a hospital-wide programme to improve compliance with hand hygiene. Lancet 2000, 356, 1307–1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yilmaz, G.; Koksal, I.; Aydin, K.; Caylan, R.; Sucu, N.; Aksoy, F. Risk Factors of Catheter-Related Bloodstream Infections in Parenteral Nutrition Catheterization. J. Parenter. Enter. Nutr. 2007, 31, 284–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- .Lagunes, L.; Rey-Pérez, A.; Martín-Gómez, M.T.; Vena, A.; de Egea, V.; Muñoz, P.; Bouza, E.; Díaz-Martín, A.; Palacios-García, I.; Garnacho-Montero, J.; et al. Association between source control and mortality in 258 patients with intra-abdominal candidiasis: A retrospective multi-centric analysis comparing intensive care versus surgical wards in Spain. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2017, 36, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Garey, K.W.; Rege, M.; Pai, M.P.; Mingo, D.E.; Suda, K.J.; Turpin, R.S.; Bearden, D.T. Time to Initiation of Fluconazole Therapy Impacts Mortality in Patients with Candidemia: A Multi-Institutional Study. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2006, 43, 25–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrell, M.; Fraser, V.J.; Kollef, M.H. Delaying the empiric treatment of Candida bloodstream infection until positive blood culture results are obtained: A potential risk factor for hospital mortality. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005, 49, 3640–3645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grim, S.A.; Berger, K.; Teng, C.; Gupta, S.; Layden, J.E.; Janda, W.M.; Clark, N.M. Timing of susceptibility-based antifungal drug administration in patients with Candida bloodstream infection: Correlation with outcomes. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2012, 67, 707–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andes, D.R.; Safdar, N.; Baddley, J.W.; Playford, G.; Reboli, A.C.; Rex, J.H.; Sobel, J.D.; Pappas, P.G.; Kullberg, B.J. Impact of treatment strategy on outcomes in patients with candidemia and other forms of invasive candidiasis: A patient-level quantitative review of randomized trials. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012, 54, 1110–1122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Giuliano, S.; Ceccarelli, G.; Renzini, V.; Magni, G.; Baisi, F.; Santini, M.; Venditti, M. Candidemia in Neurosurgical Intensive Care Unit: Preliminary analysis of the effect of topical Nystatin prophylaxis and adequate source control on patients with early tracheostomy intubation. Ann. Ig 2013, 25, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Pfaller, M.; Neofytos, D.; Diekema, D.; Azie, N.; Meier-Kriesche, H.U.; Quan, S.P.; Horn, D. Epidemiology and outcomes of candidemia in 3648 patients: Data from the Prospective Antifungal Therapy (PATH Alliance®) registry, 2004–2008. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 74, 323–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Diekema, D.; Arbefeville, S.; Boyken, L.; Kroeger, J.; Pfaller, M. The changing epidemiology of healthcare-associated candidemia over three decades. Diagn. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012, 73, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loyse, A.; Thangaraj, H.; Easterbrook, P.; Ford, N.; Roy, M.; Chiller, T.; Govender, N.; Harrison, T.S.; Bicanic, T. Cryptococcal meningitis: Improving access to essential antifungal medicines in resource-poor countries. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2013, 13, 629–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuichard, D.; Weisser, M.; Orasch, C.; Frei, R.; Heim, D.; Passweg, J.R.; Widmer, A.F. Weekly use of fluconazole as prophylaxis in haematological patients at risk for invasive candidiasis. BMC Infect. Dis. 2014, 14, 573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eggimann, P.; Que, Y.A.; Revelly, J.P.; Pagani, J.L. Preventing invasive candida infections. Where could we do better? J. Hosp. Infect. 2015, 89, 302–308. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cruciani, M.; de Lalla, F.; Mengoli, C. Prophylaxis of Candida infections in adult trauma and surgical intensive care patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Intensive Care Med. 2005, 31, 1479–1487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manzoni, P.; Stolfi, I.; Pugni, L.; Decembrino, L.; Magnani, C.; Vetrano, G.; Tridapalli, E.; Corona, G.; Giovannozzi, C.; Farina, D.; et al. A Multicenter, Randomized Trial of Prophylactic Fluconazole in Preterm Neonates. N. Engl. J. Med. 2007, 356, 2483–2495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, D.A. “Getting to Zero”: Preventing invasive Candida infections and eliminating infection-related mortality and morbidity in extremely preterm infants. Early Hum. Dev. 2012, 88, S45–S49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, C.M.; Baker, C.J.; Zaccaria, E.; Campbell, J.R. Impact of fluconazole prophylaxis on incidence and outcome of invasive candidiasis in a neonatal intensive care unit. J. Pediatr. 2005, 147, 166–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Healy, C.M. Fungal prophylaxis in the neonatal intensive care unit. NeoReviews 2008, 9, e562–e570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Healy, C.M.; Campbell, J.R.; Zaccaria, E.; Baker, C.J. Fluconazole Prophylaxis in Extremely Low Birth Weight Neonates Reduces Invasive Candidiasis Mortality Rates without Emergence of Fluconazole-Resistant Candida Species. Pediatrics 2008, 121, 703–710. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Le, J.; Tran, T.T.; Bui, I.; Wang, M.K.; Vo, A.; Adler-Shohet, F.C. Time to initiation of antifungal therapy for neonatal candidiasis. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2013, 57, 2550–2555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kludze-Forson, M.; Eschenauer, G.A.; Kubin, C.J.; Della-Latta, P.; Lam, S.W. The impact of delaying the initiation of appropriate antifungal treatment for Candida bloodstream infection. Med. Mycol. 2010, 48, 436–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Cortés, L.E.; Almirante, B.; Cuenca-Estrella, M.; Garnacho-Montero, J.; Padilla, B.; Puig-Asensio, M.; Ruiz-Camps, I.; Rodríguez-Baño, J.; Padilla, B.; Muñoz, P.; et al. Empirical and targeted therapy of candidemia with fluconazole versus echinocandins: A propensity score–derived analysis of a population-based, multicentre prospective cohort. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2016, 22, 733.e1–733.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kneale, M.; Bartholomew, J.S.; Davies, E.; Denning, D.W. Global access to antifungal therapy and its variable cost. J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 2016, 71, 3599–3606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruhnke, M. Antifungal stewardship in invasive Candida infections. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. 2014, 20, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Apisarnthanarak, A.; Yatrasert, A.; Mundy, L.M. Impact of Education and an Antifungal Stewardship Program for Candidiasis at a Thai Tertiary Care Center. Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010, 31, 722–727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopardo, G.; Titanti, P.; Berdiñas, V.; Barcelona, L.; Curcio, D. Antimicrobial stewardship program in a developing country: The epidemiological barrier. Rev. Panam. Salud Pública 2011, 30, 667–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kaufman, D.A. Aiming for Zero: Preventing Invasive Candida Infections in Extremely Preterm Infants. NeoReviews 2011, 12, e381–e392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olowe, O.; Makanjuola, O.; Olowe, R.; Adekanle, D. Prevalence of vulvovaginal candidiasis, trichomoniasis and bacterial vaginosis among pregnant women receiving antenatal care in Southwestern Nigeria. Eur. J. Microbiol. Immunol. 2014, 4, 193–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sopian, I.L.; Shahabudin, S.; Ahmed, M.A.; Lung, L.T.T.; Sandai, D. Yeast infection and diabetes mellitus among pregnant mother in Malaysia. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2016, 23, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Roy, U.; Jessani, L.G.; Rudramurthy, S.M.; Gopalakrishnan, R.; Dutta, S.; Chakravarty, C.; Jillwin, J.; Chakrabarti, A. Seven cases of Saccharomyces fungaemia related to use of probiotics. Mycoses 2017, 60, 375–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doron, S.; Snydman, D.R. Risk and safety of probiotics. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2015, 60, S129–S134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Riquelme, A.J.; Calvo, M.A.; Guzmán, A.M.; Depix, M.S.; García, P.; Pérez, C.; Arrese, M.; Labarca, J.A. Saccharomyces cerevisiae fungemia after Saccharomyces boulardii treatment in immunocompromised patients. J. Clin. Gastroenterol. 2003, 36, 41–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Atici, S.; Soysal, A.; Karadeniz Cerit, K.; Yilmaz, S.; Aksu, B.; Kiyan, G.; Bakir, M. Catheter-related Saccharomyces cerevisiae Fungemia Following Saccharomyces boulardii Probiotic Treatment: In a child in intensive care unit and review of the literature. Med. Mycol. Case Rep. 2017, 15, 33–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cassone, M.; Serra, P.; Mondello, F.; Girolamo, A.; Scafetti, S.; Pistella, E.; Venditti, M. Outbreak of Saccharomyces cerevisiae Subtype boulardii Fungemia in Patients Neighboring Those Treated with a Probiotic Preparation of the Organism. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2003, 41, 5340–5343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chitnis, A.S.; Magill, S.S.; Edwards, J.R.; Chiller, T.M.; Fridkin, S.K.; Lessa, F.C. Trends in Candida central line-associated bloodstream infections among NICUs, 1999–2009. Pediatrics 2012, 130, e46–e52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriyama, B.; Gordon, L.A.; Mccarthy, M.; Henning, S.A.; Walsh, T.J.; Penzak, S.R. Emerging drugs and vaccines for Candidemia. Mycoses 2014, 57, 718–733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Population based (n/100,000 population) (Developed countries) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | Incidence | Reference | Country | Incidence | Reference |

| North America | 13.3 to 26.2 (9.4–75 neonates; 5.2–26 elderly) | [9] | Norway | 24 | [9] |

| USA | 3.65–26.2 | [9,11,12] | Sweden | 4.2 | [9] |

| Australia | 1.81–2.41 | [9,13] | Spain | 4.3–8.1 | [9] |

| Europe | 9.4 | [9,14] | Iceland | 5.7 | [15] |

| Denmark | 8.6–9.4 | [9] | Canada | 2.8 | [9] |

| Finland | 1.9–2.86 | [9] | England and Wales | 1.52 (infants 11) | [9] |

| Hospital based data (a, per 1000 admissions; d, per 1000 discharges; pd, per 1000 patient days; py, per 1000 patient years) | |||||

| Developing Country | Incidence | Reference | Developed Country | Incidence | Reference |

| Overall Asia | a 0.39–14.2 pd 0.026–4.2 | [16,17] | USA | d 1.9–2.4 a 0.30 pd 0.46 | [11,12] |

| Korea | py 29 | [16] | Canada | a 0.45 | [9] |

| China | pd 0.026–0.05 a 0.32–0.55 | [16,17,18,19] | UK | bd 0.109 pd 0.03 a 1.87 | [9] |

| Hong Kong | pd 0.07 d 0.25 | [16,17] | Australia | a 0.21 | [13] |

| Taiwan | d 1.2–2.93 pd 0.14–2.8 | [16,17] | Switzerland | 0.049 | [9] |

| India | a 1–12 d 1.94 pd 1.24 | [8,16,17] | Sweden | a 0.32 pd 0.44 | [9] |

| Thailand | a 1.32 d 1.31 pd 0.12–0.15 | [16,17] | Belgium | a 0.44 pd 0.065 | [20] |

| Turkey | a 0.56–5.1 pd 0.058–0.30 d 0.42 | [9,16,21] | France | a 0.2–3.8 | [22] |

| Singapore | pd 0.12–0.33 | [16,17] | Spain | pd 0.073–0.136 | [9] |

| Japan | pd 0.0004–0.0008 | [9] | Italy | a 0.38–1.19 pd 0.12–0.31 | [9] |

| South Africa | a 0.28–0.36 | [23] | |||

| Latin America | a 1.01–2.63 pd 0.23 | [9,24] | |||

| Argentina | a 1.95 pd 0.24 | [9] | |||

| Venezuela | a 1.72 | [9] | |||

| Brazil | a 1.38–2.49 pd 0.26–0.37 | [9] | |||

| Honduras | a 0.90 pd 2.5 | [9] | |||

| Ecuador | a 0.90 pd 0.16 | [9] | |||

| Chile | a 0.33 pd 0.09 | [9] | |||

| Columbia | a 1.96 pd 0.16 | [9] | |||

| UAE | d 0.77 | [25] | |||

| Special groups (a, per 1000 admissions; d, per 1000 discharges; pd, per 1000 patient days; py, per 1000 patient years) | |||||

| Developing Country | Incidence | Reference | Developed Country | Incidence | Reference |

| Overall Asia; ICU | a 2.2–41 pd 2.2 a 42.7 NICU/PICU) | [17,26] | Europe; ICU | a 2.6–16.5 pd 0.07–0.33 | [9] |

| China; ICU | a 3.2 | [9] | EPIC II study; ICU | a 6.87 | [14] |

| India; ICU | a 6.51 | [26] | Germany; ICU | a 0.24 pd 0.07 | [9] |

| Turkey; ICU | a 12.3–42.7 pd 2.31 | [9,26] | France; ICU | a 6.7 | [9] |

| Korea; ICU | d 9.1 | [16] | Italy; ICU | a 0.26–1.65 pd 0.33 | [9] |

| Hong Kong; ICU | pd 2.2 | [16,17] | US; Haematological malignancy | pd 0.19 | [9] |

| Developing Countries | Crude Mortality Rate | References | Developed Countries | Crude Mortality Rate | References |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| China | 28.1–36.9% n 15.7% n 8.9% (ICU) | [18,28,29,30] | USA | 19.6–40% p 13% elbw 37% n 12–19% | [31,32,33,34] |

| Japan | 26% | [35] | Switzerland | 44–46% | [31,36] |

| India | n 34.9–40% | [37,38,39,40] | Spain | 44–47% | [31,36] |

| Pakistan | i 24–75% | [41] | Canada | 30–52% | [31,36] |

| Taiwan | 36.7–59% | [17] | Italy | 35% | [31,36] |

| Kuwait | 15–60% | [42] | Australia | 21% (SOT) | [43] |

| Brazil | 50–72.2% | [44] | USA | 26.5% (SOT) | [45] |

| South Africa | 60% | [23] | |||

| Country | C. albicans (%) | C. tropicalis (%) | C. parapsilosis (%) | C. glabrata (%) | C. krusei (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Developing Countries | |||||

| Latin America | 43.6–51.8 | 13.2–17 | 10.3–25.6 | 5.2–7.4 | 1.4 |

| Argentina | 38.4–42.5 | 15.4–16.8 | 23.9–26 | 4.3–6.2 | 0.4–1.8 |

| Brazil | 40.5 | 13.2 | 25.8 | 10 | 4.7 |

| Chile | 42.1 | 10.5 | 28.9 | 7.9 | 7.9 |

| Columbia | 36.7 | 17.4 | 38.5 | 4.6 | - |

| Ecuador | 52.2 | 10.9 | 30.4 | 4.3 | - |

| Honduras | 27.4 | 26.7 | 14.1 | 3.7 | 3 |

| Asia Pacific | 56.9–64.4 | 11.7 | 7.4–13.7 | 12.6–13.7 | 1.2–2 |

| China | 35.9–41.8 | 17.6–21.8 | 7.7–23.8 | 12.3–12.9 | - |

| India | 20.9 | 41.6 | 10.9 | - | - |

| Thailand | 35.6 | 27.1 | 15.7 | 16.3 | - |

| Turkey | 45.8 | 24.1 | 14.5 | 4.8 | - |

| Africa and Middle East | 67.1 | 6.6 | 6 | 8.8 | 1.6 |

| South Africa | 45.9 | 3.3 | 25 | 19.8 | 3.3 |

| Developed Countries | |||||

| USA | 38–48.9 | 7.3–10.5 | 13.6–17.1 | 21.1–29 | 1.9–3.4 |

| Canada | 64 | 11 | 11 | 11 | - |

| Europe | 55.2–67.9 | 4.9–7.3 | 4.2–13.3 | 11.3–15.7 | 1.9–3.4 |

| Belgium | 55 | 2.8 | 13 | 22 | 2.3 |

| Finland | 67–70 | 2–3 | 5 | 9–19 | 3–8 |

| Germany | 58.5–66 | 7.5 | 8 | 19.1 | 1.4 |

| Italy | 40.2–50.4 | 8.2–9.8 | 14.8–36.9 | 9.8–20.3 | - |

| Norway | 69.8 | 6.7 | 5.8 | 13.2 | 1.6 |

| Spain | 36.5–49 | 5.9–10.7 | 20.7–46.8 | 3.9–13.6 | 1–2.1 |

| Sweden | 60.8 | 2 | 8.9 | 20.1 | 1.2 |

| Switzerland | 68 | 9 | 1 | 15 | 2 |

| UK and Wales | 53.7–64.7 | 3.2–4.4 | 7.4–10.7 | 16.2–25.8 | 1–2.9 |

| Australia | 44.8 | 4.8 | 16.5 | 26.7 | 2.6 |

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kaur, H.; Chakrabarti, A. Strategies to Reduce Mortality in Adult and Neonatal Candidemia in Developing Countries. J. Fungi 2017, 3, 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3030041

Kaur H, Chakrabarti A. Strategies to Reduce Mortality in Adult and Neonatal Candidemia in Developing Countries. Journal of Fungi. 2017; 3(3):41. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3030041

Chicago/Turabian StyleKaur, Harsimran, and Arunaloke Chakrabarti. 2017. "Strategies to Reduce Mortality in Adult and Neonatal Candidemia in Developing Countries" Journal of Fungi 3, no. 3: 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3030041

APA StyleKaur, H., & Chakrabarti, A. (2017). Strategies to Reduce Mortality in Adult and Neonatal Candidemia in Developing Countries. Journal of Fungi, 3(3), 41. https://doi.org/10.3390/jof3030041