Genotype and Organ-Specific Variability in Antioxidant Capacities as Well as Polyamine and Osmolyte Levels in Eleven Lisianthus (Eustoma grandiflorum Raf.) Cultivars with Different Flowering Periods

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- i.

- To achieve that, we have quantified the concentrations of osmolytes (proline (PRO) and glycine betaine (GB)), PAs, phenols, and flavonoids in eleven different lisianthus cultivars with varying flowering periods, at leaf and petal levels.

- ii.

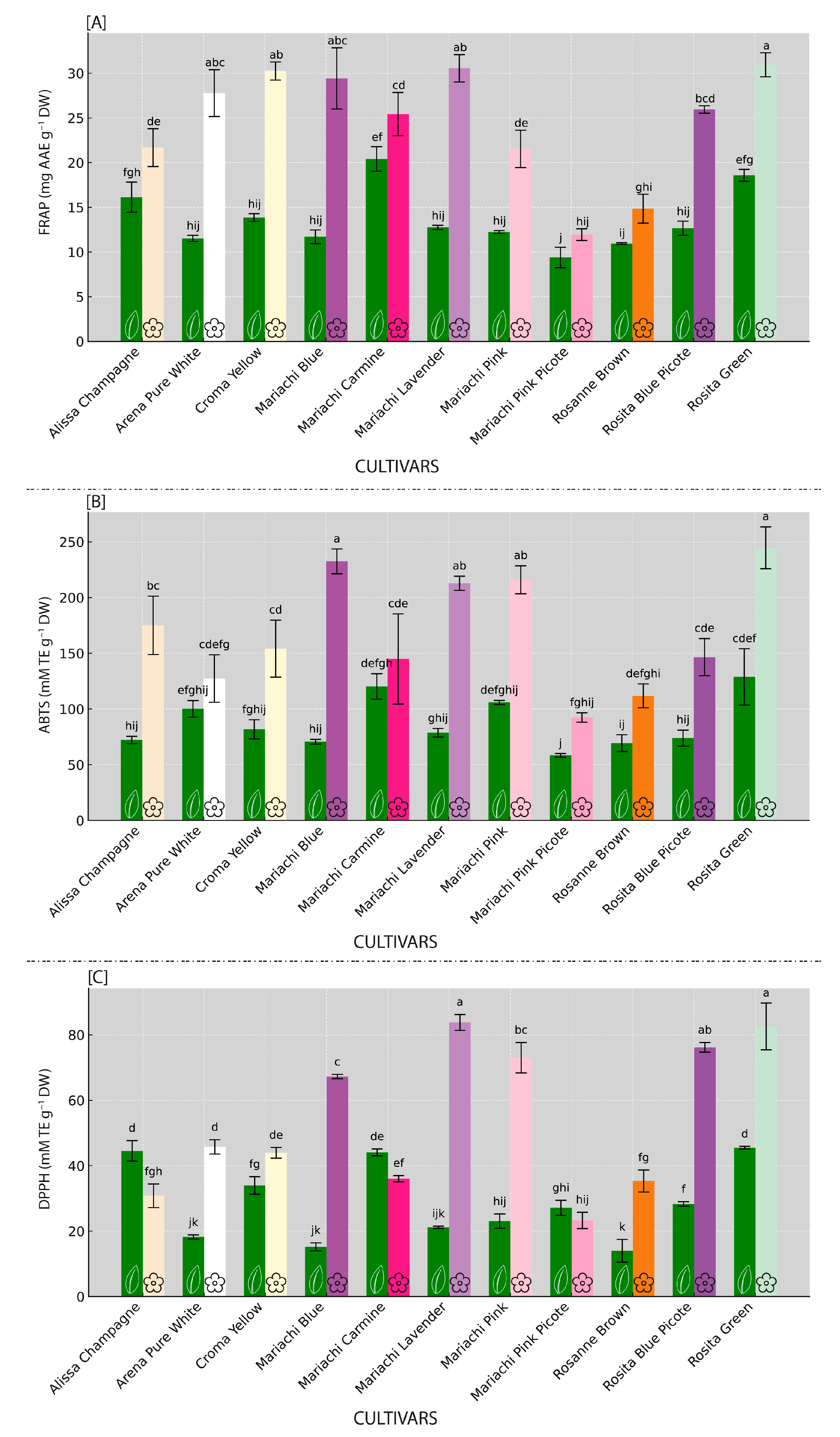

- We also assessed the antioxidant capacities of lisianthus cultivar extracts by using FRAP (ferric reducing antioxidant power), DPPH (2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl), and ABTS (2,2′-azino-bis-(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic) acid) assays to establish the correlation between specific metabolites and total antioxidant capacities.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Plant Material and Sample Preparation

2.2. Quantification of Polyamines (PAs) by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography

2.3. Spectrophotometric Quantification of Proline (PRO) and Glycine Betaine (GB)

- (a)

- Proline Content Determination: In 25 mg of freeze-dried plant material (particularly the petals and leaves), 2 mL of sulfosalicylic acid (3% w/v) was added. After centrifugation at 4000 rpm for 20 min, 0.7 mL of the supernatant was added to 0.7 mL of acid ninhydrin solution (2.5% ninhydrin in glacial acetic acid-distilled water and 85% orthophosphoric acid in a 6:3:1 ratio) and 0.7 mL of glacial acetic acid, then heated at 95 °C for 1 h. After heating, the tubes were placed in an ice bath to stop the reaction. The pinkish-colored compound resulting from the reaction of PRO and ninhydrin was extracted with 1 mL of toluene by vigorous vortexing. When the layers separated and the solution reached room temperature, the PRO concentration was determined spectrophotometrically at 520 nm using the MultiScan GO (ThermoScientific, Bremen, Germany) according to the method previously described by Bates et al. [23] The concentration of free PRO was determined using a standard calibration curve and expressed as micromoles per gram of dry weight (μmol g−1 DW).

- (b)

- Determination of Glycine Betaine Content: In 25 mg of freeze-dried plant material, 1 mL of 1M H2SO4 was added with vigorous vortexing. The extraction continued in an ultrasonic bath for 10 min. After extraction, the samples were centrifuged at 13,200 rpm at 4 °C for 30 min. Following centrifugation, 500 μL of the supernatant was combined with 200 μL of KI/I2, and the solution was left for 16 h at 4 °C. After a second centrifugation under the same conditions, QAC–periodide crystals in the sediment were dissolved in 2 mL of 1,2-dichloroethane using an ultrasonic bath. The absorbance of the mixture was measured at a wavelength of 365 nm using a MultiScan GO spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific, Bremen, Germany). GB concentration was determined from a standard calibration curve, and the GB content was expressed as µmol g−1 DW [24].

2.4. Evaluation of Lisianthus Petal and Leaf Antioxidant Capacities

2.5. Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Content Qunatification

2.6. Statistical Data Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Variability in Total Phenolic and Flavonoid Contents Among Lisianthus Cultivars

3.2. Antioxidant Capacities Variability (FRAP, ABTS, DPPH) Across Lisianthus Cultivars

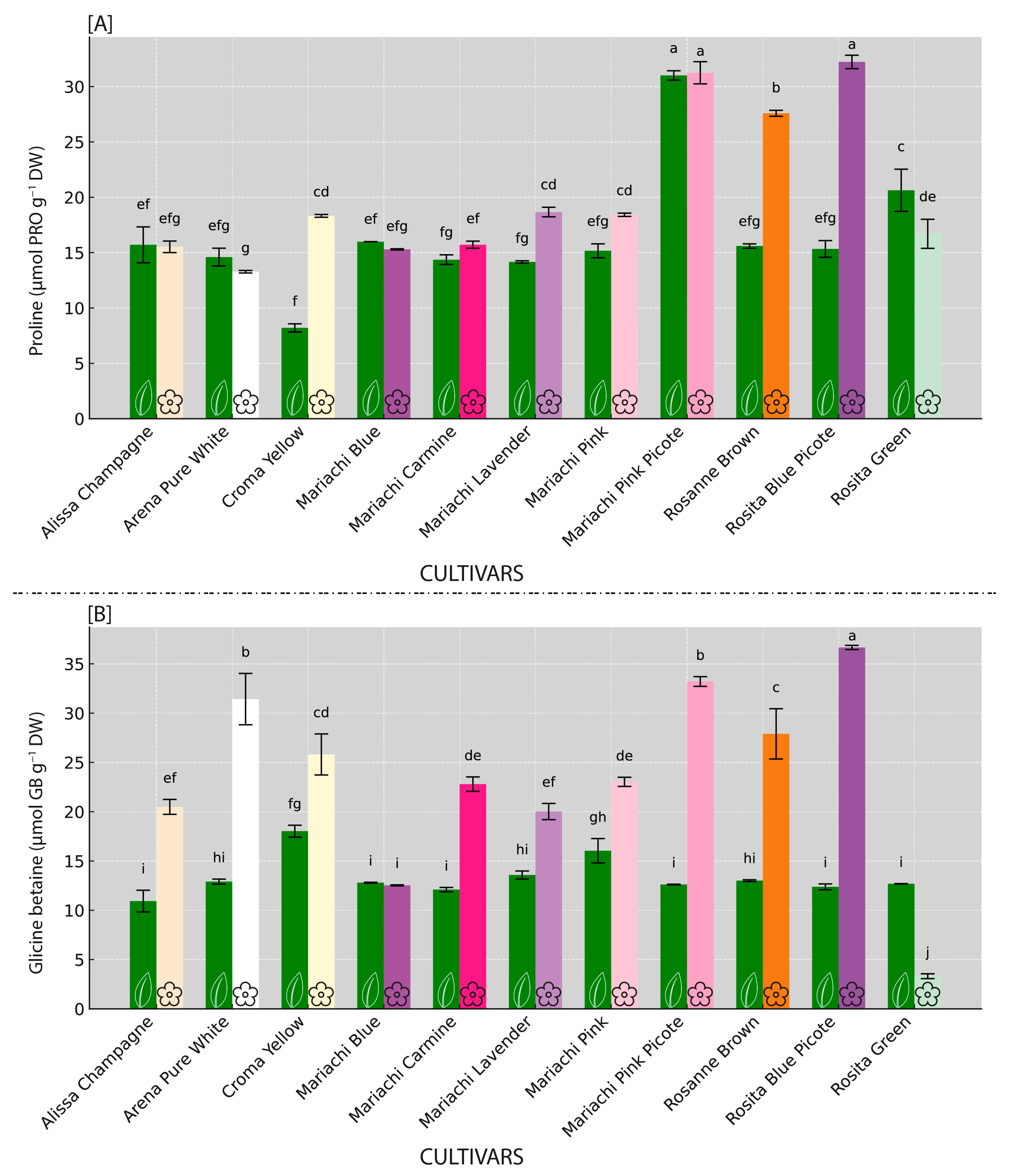

3.3. Osmolyte Variability Among Inspected Lisianthus Cultivars

3.4. Polyamine Profiling Within Inspected Lisianthus Cultivars

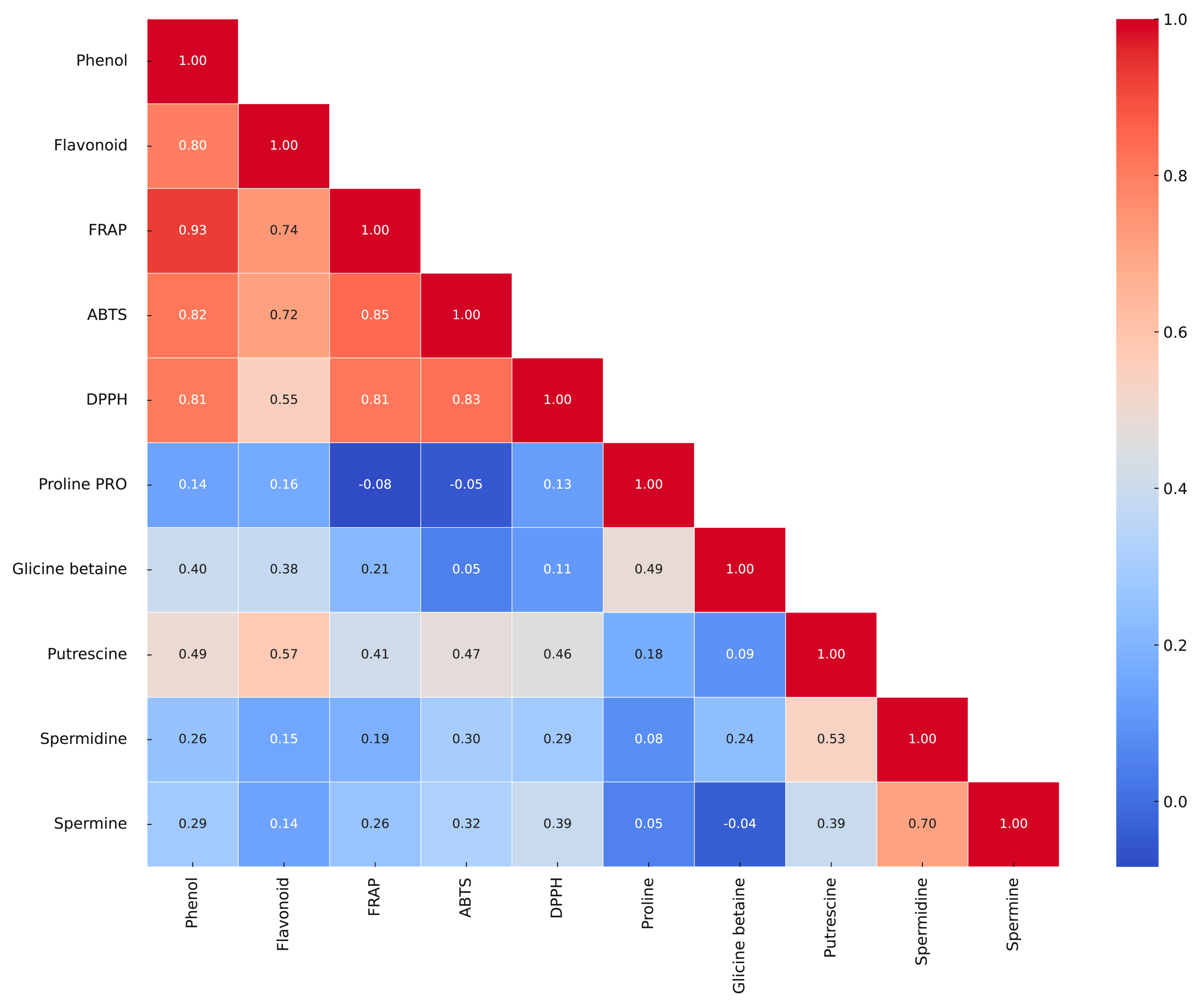

3.5. Correlation Matrix

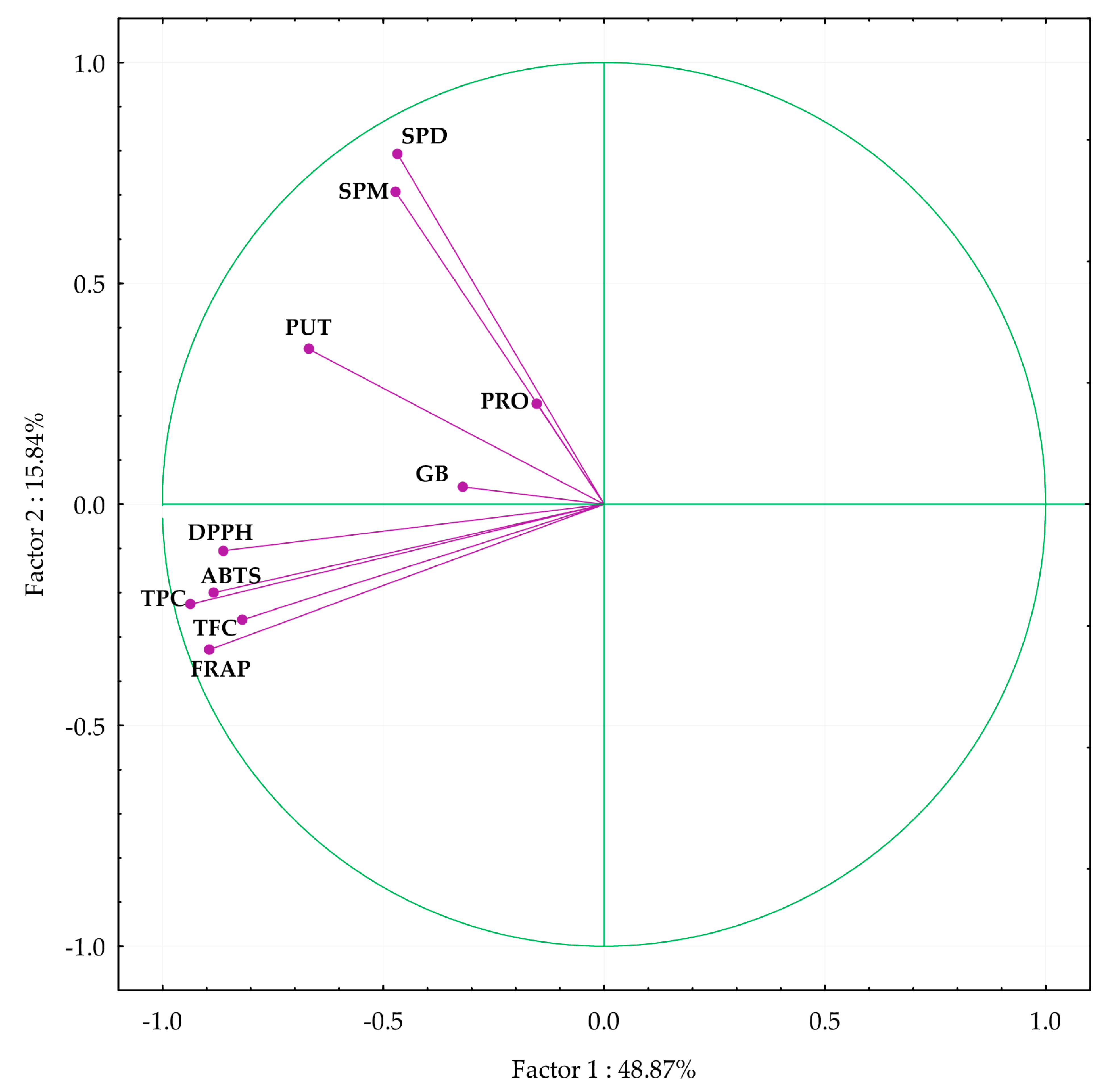

3.6. Principal Component Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhang, P.; Sun, Y.; Zhou, J.; Li, J.; Yu, R.; Ruan, J.; Yang, C.; Jin, C.; Li, F.; Wang, J. Specific responses in soil metabolite alteration and fungal community decline to the long-term monocropping of Lisianthus. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 337, 113578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitawati, S.; Nurlaelih, E.; Daraini, M. Improved quality of lisianthus (Eustoma grandiflorum raf. Shinn.) with plant spacing and pinching frequency. J. Innov. Sci. Inform. Serv. 2018, 15, 280–286. [Google Scholar]

- Harbaugh, B.K. Lisianthus. In Flower Breeding and Genetics Issues, Challenges and Opportunities for the 21st Century, 1st ed.; Anderson, N.O., Ed.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2007; pp. 644–663. [Google Scholar]

- Uddin, A.J.; Islam, M.S.; Mehraj, H.; Roni, M.Z.K.; Shahrin, S. An evaluation of some Japanese lisianthus (Eustoma grandiflorum) varieties grown in Bangladesh. Agriculturists 2013, 11, 56–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumaresan, M.; Rajaselvam, M.; Devi, K.N.; Vasanthkumar, S.S. A newly emerging potential cut flower of Lisianthus (Eustoma grandiflorum) in Tamil Nadu: A review. Ecol. Environ. Conserv. 2024, 30, 790–795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuksanović, V.; Kovačević, B.; Kebert, M.; Pavlović, L.; Kesić, L.; Čukanović, J.; Orlović, S. In vitro selection of drought-tolerant white poplar clones based on antioxidant activities and osmoprotectant content. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1280794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kebert, M.; Rašeta, M.; Kostić, S.; Vuksanović, V.; Božanić Tanjga, B.; Ilić, O.; Orlović, S. Metabolically tailored selection of ornamental Rose cultivars through polyamine profiling, osmolyte quantification and evaluation of antioxidant activities. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L. The effect of polyamineon flower bud differentiation and bud germination of chrysanthemum. Shandong Agric. Univ. 2015, 2, 31–36. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; Shao, Q.; Yin, L.; Younis, A.; Zheng, B. Polyamine function in plants: Metabolism, regulation on development, and roles in abiotic stress responses. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 9, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahrami, S.N.; Zakizadeh, H.; Hamidoghli, Y.; Ghasemnezhad, M. Salicylic acid retards petal senescence in cut Lisianthus (Eustoma grandiflorum “Miarichi Grand White”) flowers. Hortic. Environ. Biotechnol. 2013, 54, 519–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piri, M.; Jabbarzadeh, Z. Plant growth regulators’ role in senescence and quality of lisianthus (Eustoma grandiflorum ‘Mariachi Blue’) cut flowers: Comparison salicylic acid (SA), sodium nitroprusside (SNP) and spermidine (Sp). 2023; preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sagor, G.H.M.; Kusano, T.; Berberich, T. A polyamine oxidase from Selaginella lepidophylla (SelPAO5) can replace AtPAO5 in arabidopsis through converting thermospermine to norspermidine instead to spermidine. Plants 2019, 8, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cavaiuolo, M.; Cocetta, G.; Ferrante, A. The antioxidants changes in ornamental flowers during development and senescence. Antioxidants 2013, 2, 132–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattoo, A.K.; Sobieszczuk-Nowicka, E. Polyamine as signaling molecules and leaf senescence. In Senescence Signalling and Control in Plants, 1st ed.; Sarwat, M., Tuteja, N., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; Volume 8, pp. 125–138. [Google Scholar]

- Rivero, R.M.; Kojima, M.; Gepstein, A.; Sakakibara, H.; Mittler, R.; Gepstein, S.; Blumwald, E. Delayed leaf senescence induces extreme drought tolerance in a flowering plant. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 19631–19636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wojciechowska, N.; Sobieszczuk-Nowicka, E.; Bagniewska-Zadworna, A. Plant organ senescence—regulation by manifold pathways. Plant Biol. 2018, 20, 167–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohammadi, M.; Aelaei, M.; Saidi, M. Pre-harvest and pulse treatments of spermine, γ- and β-aminobutyric acid increased antioxidant activities and extended the vase life of gerbera cut flowers “Stanza”. Ornam. Hortic. 2020, 26, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabnawaz, A.; Ahmad, R.; Anjum, M.A. Effect of seed priming on growth, flowering and cut flower quality of carnation. Indian J. Hortic. 2020, 77, 527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuksanović, V.; Kovačević, B.; Stojnić, S.; Kebert, M.; Kesić, L.; Galović, V.; Orlović, S. Variability of tolerance of wild cherry clones to PEG-Induced osmotic stress in vitro. iForest 2022, 15, 265–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzma, J.; Talla, S.; Madam, E.; Mamidala, P. Salinity-driven oxidative stress in Gerbera jamesonii cv. Bolus. J. Appl. Hortic. 2022, 24, 240–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scaramagli, S.; Franceschetti, M.; Michael, A.J.; Torrigiani, P.; Bagni, N. Polyamines and Flowering: Spermidine biosynthesis in the different whorls of developing flowers of Nicotiana tabacum L. Plant Biosyst. 1999, 133, 229–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biondi, S.; Antognoni, F.; Marincich, L.; Lianza, M.; Tejos, R.; Ruiz, K.B. The polyamine “multiverse” and stress mitigation in crops: A case study with seed priming in quinoa. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 304, 111292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bates, L.S.; Waldren, R.P.; Teare, I.D. Rapid determination of free proline for water-stress studies. Plant Soil 1973, 39, 205–207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashraf, M.; Foolad, M.R. Roles of glycine betaine and proline in improving plant abiotic stress resistance. Environ. Exp. Bot. 2007, 59, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benzie, I.F.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miller, N.J.; Rice-Evans, C.A. Factors influencing the antioxidant activity determined by the ABTS radical cation assay. Free Rad. Res. 1997, 26, 195–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, D.O.; Jeong, S.W.; Lee, C.Y. Antioxidant capacity of phenolic phytochemicals from various cultivars of plums. Food Chem. 2003, 81, 321–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, C.-C.; Yang, M.-H.; Wen, H.-M.; Chern, J.-C. Estimation of total flavonoid content in propolis by two complementary colorimetric methods. J. Food Drug Anal. 2002, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TIBCO Software Inc. Data Science Workbench. 2020. Available online: http://www.tibco.com/products/data-science (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Wickham, H. ggplot2: Elegant Graphics for Data Analysis; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Available online: https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/ggplot2/index.html (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Wei, T.; Simko, V. R package ‘corrplot’: Visualization of a Correlation Matrix. 2021. Available online: https://github.com/taiyun/corrplot (accessed on 1 September 2024).

- Davies, K.M.; Marie Bradley, J.; Schwinn, K.E.; Markham, K.R.; Podivinsky, E. Flavonoid biosynthesis in flower petals of five lines of Lisianthus (Eustoma grandiflorum Grise.). Plant Sci. 1993, 95, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmitzer, V.; Veberic, R.; Osterc, G.; Stampar, F. Color and phenolic content changes during flower development in groundcover rose. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 2010, 135, 195–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asen, S.; Griesbach, R.J.; Norris, K.H.; Leonhardt, B.A. Flavonoids from Eustoma grandiflorum flower petals. Phytochemistry 1986, 25, 2509–2513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaghoobi Kiaseh, D.; Hashemabadi, D.; Kaviani, B. Proline and arginine improves the vase life of cut alstroemeria ‘mars’ flowers by regulating some postharvest physiochemical parameters. J. Ornam. Plants 2021, 11, 165–183. [Google Scholar]

- Kumar, N.; Pal, M.; Singh, A.; Kumar SaiRam, R.; Chand Srivastava, G. Exogenous proline alleviates oxidative stress and increase vase life in rose (Rosa hybrida L. “Grand Gala”). Sci. Hortic. 2010, 127, 79–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Pal, M.; Srivastava, G.C. Proline metabolism in senescing rose petals (Rosa hybrida L. “First Red”). J. Hortic. Sci. Biotech. 2009, 84, 536–540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soroori, S.; Danaee, E.; Hemmati, K.; Moghadam, A.L. Effect of foliar application of proline on morphological and physiological traits of Calendula officinalis L. under drought stress. J. Ornam. Plants 2021, 11, 13–30. [Google Scholar]

- Murmu, K.; Murmu, S.; Kumar Kundu, C.; Sekhar Bera, P. Exogenous proline and glycine betaine in plants under stress tolerance. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. Appl. Sci. 2017, 6, 901–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorwong, A.; Sakhonwasee, S. Foliar application of glycine betaine mitigates the effect of heat stress in three marigold (Tagetes erecta) cultivars. Hort. J. 2015, 84, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Zhi, H.; Dong, Y. Influence of preharvest and postharvest applications of glycine betaine on fruit quality attributes and storage disorders of “lapins” and “regina” cherries. HortScience 2019, 54, 1540–1545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahi, M.; Khalighi, A.; Kholdbarin, B.; Mashhadi, M.; Eshghi, S. Morphological responses and vase life of Rosa hybrida cv. dolcvita to polyamines spray in hydroponic system. World Appl. Sci. J. 2013, 21, 1681–1686. [Google Scholar]

- Bagni, N.; Tassoni, A. The role of polyamines in relation to flower senescence. Floric. Ornam. Plant Biotechnol. 2006, 1, 88–95. [Google Scholar]

- Hojatipour, M.; Hassanpour Asil, M. Effect of gibberellic acid and putrescine on growth, flowering and vase life of lily cut flower (‘Lesotho’). J. Hortic. Sci. 2022, 36, 163–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piri, M.; Jabbarzadeh, Z. The effect of foliar application of salicylic acid, spermidine and sodium nitroprusside on some growth and flowering characteristics, photosynthetic pigments and vase life of Lisianthus “mariachi blue”. J. Hortic. Sci. 2023, 36, 917–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tun, N.N.; Santa-Catarina, C.; Begum, T.; Silveira, V.; Handro, W.; Floh, E.I.S.; Scherer, G.F. Polyamines induce rapid biosynthesis of nitric oxide (NO) in Arabidopsis thaliana seedlings. Plant Cell Physiol. 2006, 47, 346–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, N.; Gautam, A.; Dubey, A.K. Polyamines metabolism and NO signaling in plants. In Nitric Oxide in Plant Biology; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2022; pp. 345–372. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, D.; Ou, B.; Prior, R.L. The chemistry behind antioxidant capacity assays. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2005, 53, 1841–1856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Cultivar Name | Harvest Period | Other Characteristics | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mariachi Blue | Summer (July, August) |

|

| Mariachi Pink | Summer (July, August) |

|

| Mariachi Carmine | Summer (July, August) |

|

| Mariachi Pink Picote | Summer (July, August) |

|

| Mariachi Lavender | Summer (July, August) |

|

| Alissa Champagne | Summer (July, August) |

|

| Croma Yellow | Fall (September) |

|

| Rosita Green | Summer (July, August) |

|

| Arena Pure White | Spring to early summer (May, June) |

|

| Rosanne Brown | Fall (September) |

|

| Rosita Blue Picote | Spring to early summer (May, June) |

|

| Trait | Cultivar (A) | Organ (B) | Interaction (AXB) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total phenolic content | 87.6 ** | 3639.5 ** | 40.9 ** |

| Total flavonid content | 106.7 ** | 3445.7 ** | 72.18 ** |

| Ferric reducing antioxidant power | 47.5 ** | 871.6 ** | 22.9 ** |

| ABTS radical scavenging activity | 24.3 ** | 435.7 ** | 12.9 ** |

| DPPH radical scavenging activity | 117.3 ** | 1470.0 ** | 143.6 ** |

| Proline content | 302.5 ** | 437.0 ** | 113.1 ** |

| Glycine betaine | 144.9 ** | 1548.1 ** | 129.2 ** |

| Putrescine | 21.0 ** | 93.7 ** | 19.5 ** |

| Spermidine | 19.1 ** | 22.0 * | 3.4 ** |

| Spermine | 17.1 ** | 6.0 ** | 8.4 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vuksanović, V.; Kebert, M.; Pavlović, L.; Kesić, L.; Rašeta, M.; Kovačević, B.; Orlović, S. Genotype and Organ-Specific Variability in Antioxidant Capacities as Well as Polyamine and Osmolyte Levels in Eleven Lisianthus (Eustoma grandiflorum Raf.) Cultivars with Different Flowering Periods. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae10111193

Vuksanović V, Kebert M, Pavlović L, Kesić L, Rašeta M, Kovačević B, Orlović S. Genotype and Organ-Specific Variability in Antioxidant Capacities as Well as Polyamine and Osmolyte Levels in Eleven Lisianthus (Eustoma grandiflorum Raf.) Cultivars with Different Flowering Periods. Horticulturae. 2024; 10(11):1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae10111193

Chicago/Turabian StyleVuksanović, Vanja, Marko Kebert, Lazar Pavlović, Lazar Kesić, Milena Rašeta, Branislav Kovačević, and Saša Orlović. 2024. "Genotype and Organ-Specific Variability in Antioxidant Capacities as Well as Polyamine and Osmolyte Levels in Eleven Lisianthus (Eustoma grandiflorum Raf.) Cultivars with Different Flowering Periods" Horticulturae 10, no. 11: 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae10111193

APA StyleVuksanović, V., Kebert, M., Pavlović, L., Kesić, L., Rašeta, M., Kovačević, B., & Orlović, S. (2024). Genotype and Organ-Specific Variability in Antioxidant Capacities as Well as Polyamine and Osmolyte Levels in Eleven Lisianthus (Eustoma grandiflorum Raf.) Cultivars with Different Flowering Periods. Horticulturae, 10(11), 1193. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae10111193