Exploring Wild and Local Fruits as Sources of Promising Biocontrol Agents against Alternaria spp. in Apples

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Pathogens

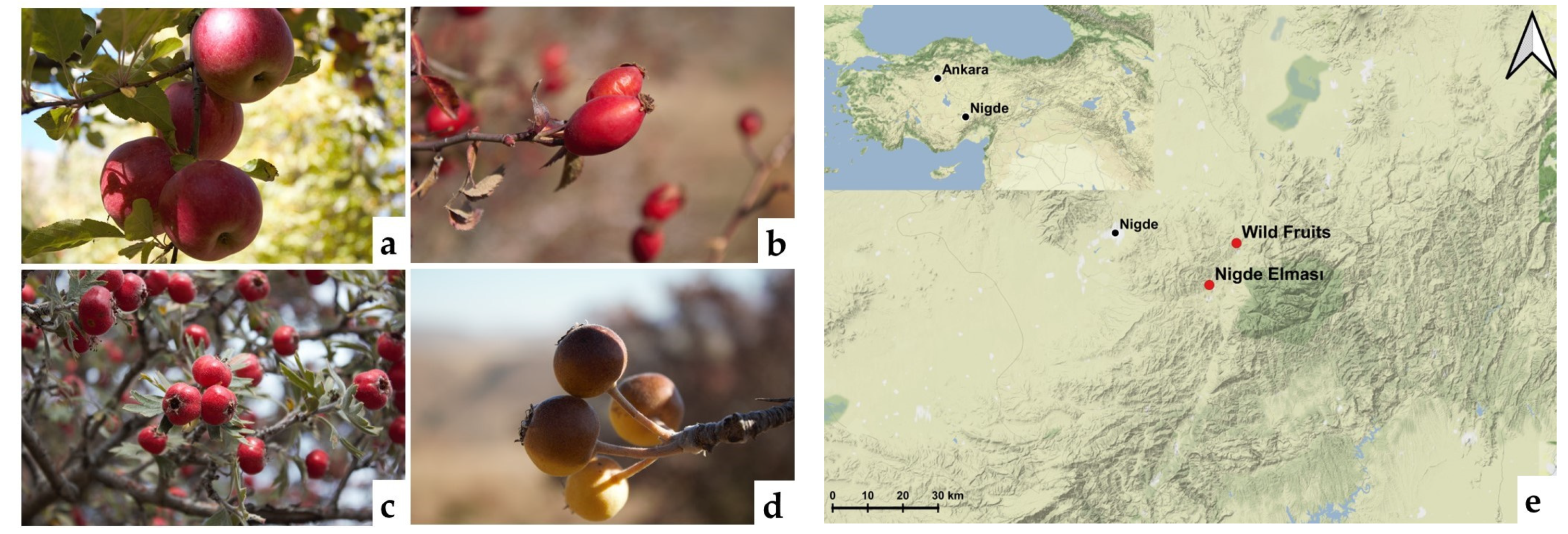

2.2. Fruits

2.3. Sampling and Yeast Isolation

2.4. Primary Screening for Antagonistic Yeast

2.5. Two-Step In Vivo Biocontrol Screening

2.6. Volatile and Non-Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs and nVOCs)

2.7. Molecular Identification

2.8. Data Analysis

3. Results

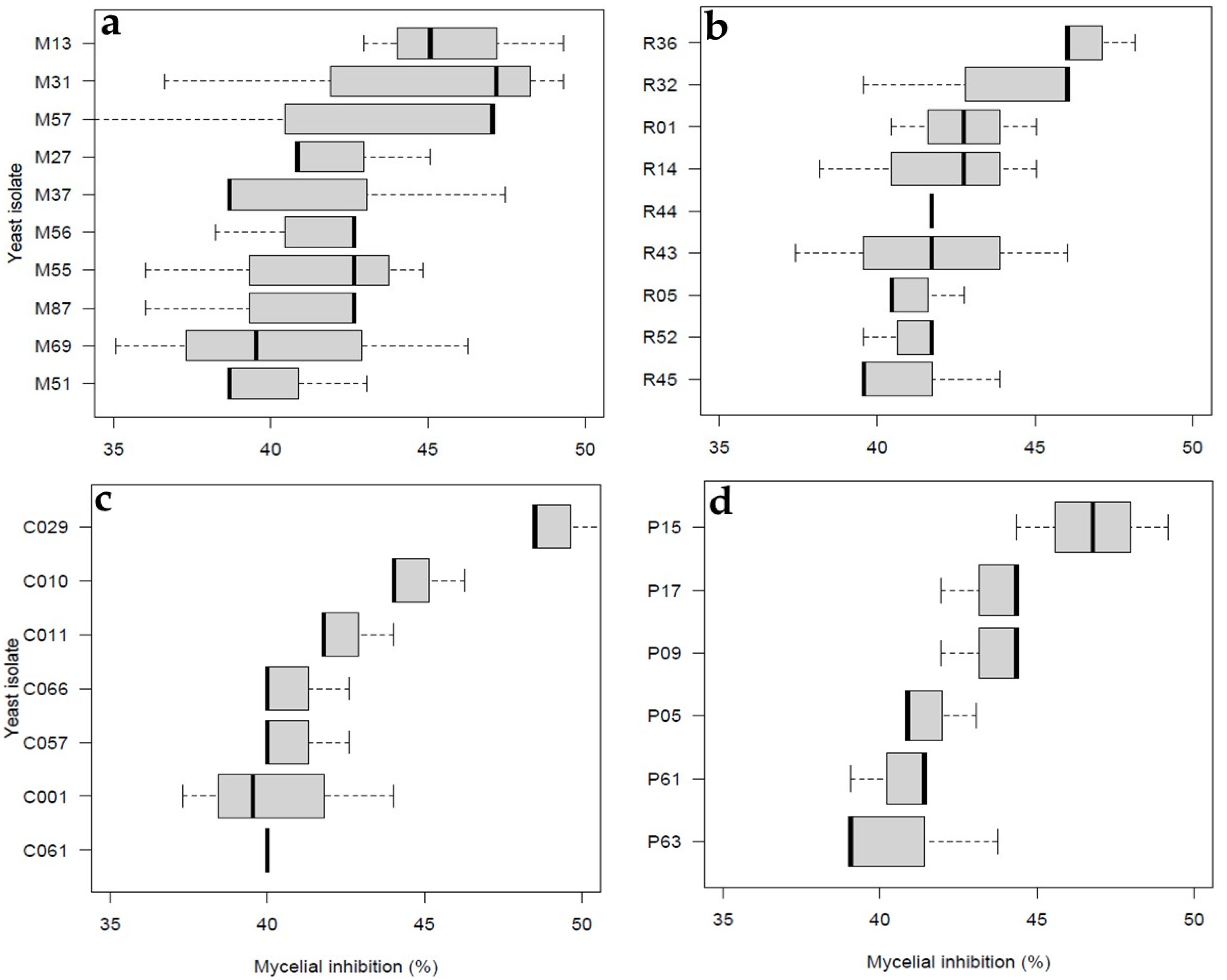

3.1. Primary Screening for Antagonistic Yeast

3.2. Molecular Identification of Candidate Yeast Isolates

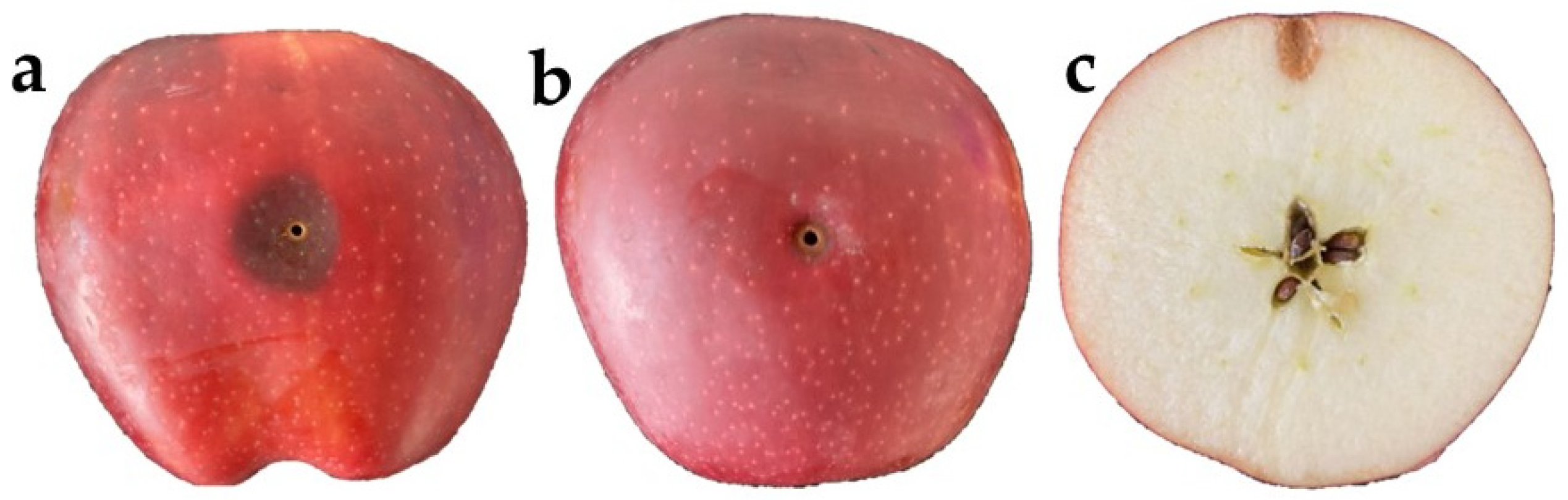

3.3. Biocontrol Screening

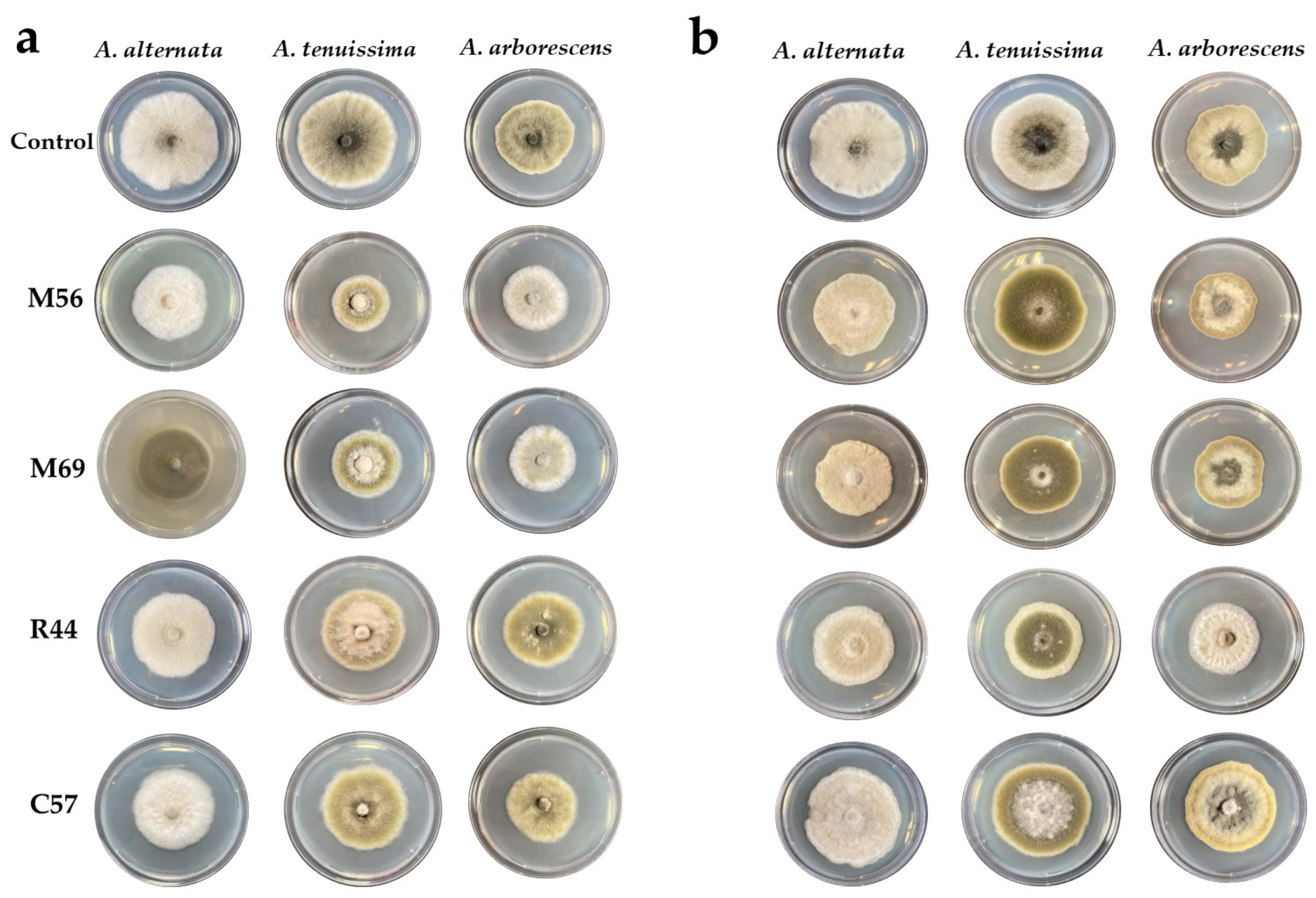

3.4. Volatile and Non-Volatile Organic Compounds (VOCs and nVOCs)

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hernandez-Montiel, L.G.; Droby, S.; Preciado-Rangel, P.; Rivas-García, T.; González-Estrada, R.R.; Gutiérrez-Martínez, P.; Ávila-Quezada, G.D. A sustainable alternative for postharvest disease management and phytopathogens biocontrol in fruit: Antagonistic Yeasts. Plants 2021, 10, 2641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food and Agriculture Organization, FAOSTAT. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/?#data/QCL (accessed on 1 September 2023).

- Naets, M.; Bossuyt, L.; De Coninck, B.; Keulemans, W.; Geeraerd, A. Exploratory study on postharvest pathogens of ‘Nicoter’ apple in Flanders (Belgium). Sci. Hortic. 2020, 260, 108872. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurick, W.M.; Kou, L.P.; Gaskins, V.L.; Luo, Y.G. First report of Alternaria alternata causing postharvest decay on apple fruit during cold storage in Pennsylvania. Plant Dis. 2014, 98, 690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavicich, M.A.; Cárdenas, P.; Pose, G.N.; Fernández Pinto, V.; Patriarca, A. From field to process: How storage selects toxigenic Alternaria spp. causing moldy core in Red Delicious apples. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 322, 108575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeShields, J.B.; Kc, A.N. Morphological and molecular characterization of Alternaria spp. ısolated from European pears. Plant Dis. 2021, 105, 2531–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elfar, K.; Zoffoli, J.P.; Latorre, B.A. Identification and characterization of Alternaria species associated with moldy core of apple in Chile. Plant Dis. 2018, 102, 2158–2169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, A.; Mao, X.; Sun, Q.; Wei, Z.; Li, J.; You, Y.; Zhao, J.; Jiang, G.; Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; et al. Alternaria mycotoxins: An overview of toxicity, metabolism, and analysis in food. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2021, 69, 7817–7830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisniewski, M.; Droby, S. The postharvest microbiome: The other half of sustainability. Biol. Control 2019, 137, 104025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teixidó, N.; Usall, J.; Torres, R. Insight into a successful development of biocontrol agents: Production, formulation, packaging, and shelf life as key aspects. Horticulturae 2022, 8, 305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencer, O.; Serçe, S. Determination of morphological, pomological and molecular variations among apples in Niğde, Turkey using iPBS primers. Tarım Bilim. Derg. 2021, 28, 296–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janisiewicz, W.J.; Kurtzman, C.P.; Buyer, J.S. Yeasts associated with nectarines and their potential for biological control of brown rot. Yeast 2010, 27, 389–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janisiewicz, W.J.; Jurick, W.M.; Peter, K.A.; Kurtzman, C.P.; Buyer, J.S. Yeasts associated with plums and their potential for controlling brown rot after harvest: Plum yeasts. Yeast 2014, 31, 207–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Francesco, A.; Ugolini, L.; Lazzeri, L.; Mari, M. Production of volatile organic compounds by Aureobasidium pullulans as a potential mechanism of action against postharvest fruit pathogens. Biol. Control 2015, 81, 8–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meena, M.; Swapnil, P.; Zehra, A.; Dubey, M.K.; Upadhyay, R.S. Antagonistic assessment of Trichoderma spp. by producing volatile and non-volatile compounds against different fungal pathogens. Arch. Phytopathol. Plant Prot. 2017, 50, 629–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, M.; Rohani, M.; Fani, S.R.; Mosavian, M.T.H.; Probst, C.; Khodaygan, P. Biocontrol potential of native yeast strains against Aspergillus flavus and aflatoxin production in pistachio. Food Addit. Contam. Part A 2020, 37, 1963–1973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lodhi, M.A.; Ye, G.-N.; Weeden, N.F.; Reisch, B.I. A simple and efficient method for DNA extraction from grapevine cultivars and Vitis species. Plant Mol. Biol. Report. 1994, 12, 6–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- White, T.J.; Bruns, T.; Lee, S.; Taylor, J. Amplification and direct sequencing of fungal ribosomal RNA genes for phylogenetics. In PCR Protocols: A Guide to Methods and Applications; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 315–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbone, I.; Kohn, L.M. A method for designing primer sets for speciation studies in filamentous Ascomycetes. Mycologia 1999, 91, 553–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zalar, P.; Gostinčar, C.; De Hoog, G.S.; Uršič, V.; Sudhadham, M.; Gunde-Cimerman, N. Redefinition of Aureobasidium pullulans and its varieties. Stud. Mycol. 2008, 61, 21–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okonechnikov, K.; Golosova, O.; Fursov, M. Unipro UGENE: A unified bioinformatics toolkit. Bioinformatics 2012, 28, 1166–1167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gouy, M.; Tannier, E.; Comte, N.; Parsons, D.P. Seaview Version 5: A multiplatform software for multiple sequence alignment, molecular phylogenetic analyses, and tree reconciliation. In Multiple Sequence Alignment: Methods and Protocols; Katoh, K., Ed.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2021; Volume 2231, pp. 241–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Głos, H.; Bryk, H.; Michalecka, M.; Puławska, J. The recent occurrence of biotic postharvest diseases of apples in Poland. Agronomy 2022, 12, 399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretscher, J.; Fischkal, T.; Branscheidt, S.; Jäger, L.; Kahl, S.; Schlander, M.; Thines, E.; Claus, H. Yeasts from different habitats and their potential as biocontrol agents. Fermentation 2018, 4, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Canito, A.; Mateo-Vargas, M.A.; Mazzieri, M.; Cantoral, J.; Foschino, R.; Cordero-Bueso, G.; Vigentini, I. The role of yeasts as biocontrol agents for pathogenic fungi on postharvest grapes: A review. Foods 2021, 10, 1650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, D.; Spadaro, D.; Garibaldi, A.; Gullino, M.L. Selection and evaluation of new antagonists for their efficacy against postharvest brown rot of peaches. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2010, 55, 174–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gunde-Cimerman, N.; Zalar, P.; Hoog, S.; Plemenitaš, A. Hypersaline waters in salterns—Natural ecological niches for halophilic black yeasts. FEMS Microbiol. Ecol. 2000, 32, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Francesco, A.; Zajc, J.; Stenberg, J.A. Aureobasidium spp.: Diversity, versatility, and agricultural utility. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gostinčar, C.; Ohm, R.A.; Kogej, T.; Sonjak, S.; Turk, M.; Zajc, J.; Zalar, P.; Grube, M.; Sun, H.; Han, J.; et al. Genome sequencing of four Aureobasidium pullulans varieties: Biotechnological potential, stress tolerance, and description of new species. BMC Genom. 2014, 15, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Öztekin, S.; Karbancioglu-Guler, F. Biological control of green mould on mandarin fruit through the combined use of antagonistic yeasts. Biol. Control 2023, 180, 105186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parafati, L.; Vitale, A.; Restuccia, C.; Cirvilleri, G. Biocontrol ability and action mechanism of food-isolated yeast strains against Botrytis cinerea causing post-harvest bunch rot of table grape. Food Microbiol. 2015, 47, 85–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cignola, R.; Boato, A.; Sadallah, A.; Firrao, G.; Di Francesco, A. Molecular characterization of Aureobasidium spp. strains isolated during the cold season. A preliminary efficacy evaluation as novel potential biocontrol agents against postharvest pathogens. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2023, 167, 221–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Francesco, A.; Di Foggia, M.; Baraldi, E. Aureobasidium pullulans volatile organic compounds as alternative postharvest method to control brown rot of stone fruits. Food Microbiol. 2020, 87, 103395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agirman, B.; Erten, H. Biocontrol ability and action mechanisms of Aureobasidium pullulans GE17 and Meyerozyma guilliermondii KL3 against Penicillium digitatum DSM2750 and Penicillium expansum DSM62841 causing postharvest diseases. Yeast 2020, 37, 437–448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vero, S.; Mondino, P.; Burgueño, J.; Soubes, M.; Wisniewski, M. Characterization of biocontrol activity of two yeast strains from Uruguay against blue mold of apple. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2002, 26, 91–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yalage Don, S.M.; Schmidtke, L.M.; Gambetta, J.M.; Steel, C.C. Aureobasidium pullulans volatilome identified by a novel, quantitative approach employing SPME-GC-MS, suppressed Botrytis cinerea and Alternaria alternata in vitro. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 4498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosqueiro, A.S.; Bizarria, R., Jr.; Rosa-Magri, M.M. Biocontrol of post-harvest tomato rot caused by Alternaria arborescens using Torulaspora indica. Biocontrol Sci. Technol. 2023, 33, 115–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maluleke, E.; Jolly, N.P.; Patterton, H.G.; Setati, M.E. Antifungal activity of non-conventional yeasts against Botrytis cinerea and non-Botrytis grape bunch rot fungi. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 986229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmy, N.M.; Parang, K. Cyclic peptides with antifungal properties derived from bacteria, fungi, plants, and synthetic sources. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Species | Isolates | GenBank Accession Number * | |

|---|---|---|---|

| ITS | EF1 | ||

| Aureobasidium pullulans | CBS 100524 | FJ150905 | FJ157900 |

| A. pullulans | CBS 584.75 | FJ150906 | FJ57895 |

| A. pullulans | CBS 100,280 | FJ150910 | FJ157906 |

| A. melanogenum | CBS 110,373 | FJ150887 | FJ039810 |

| A. melanogenum | CBS 105.22 | FJ150886 | FJ157887 |

| A. subglaciale | EXF-2481 | FJ150895 | FJ157911 |

| A. subglaciale | EXF-2479 | FJ150893 | FJ157910 |

| A. namibiae | CBS 147.97 | FJ150875 | na |

| A. microstictum | CBS 114.64 | FJ150873 | FJ157914 |

| Isolate ID | Species Identification | Origin | Accession Number | Identity (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| M13 | Aureobasidium pullulans | Apple, fruit | JX462671 | 99.28 |

| M27 | A. pullulans | Apple, fruit | KT722604 | 99.45 |

| M31 | A. pullulans | Apple, fruit | MK460995 | 99.81 |

| M37 | A. pullulans | Apple, fruit | MK460995 | 100.00 |

| M51 | A. pullulans | Apple, fruit | MK460995 | 99.27 |

| M55 | A. pullulans | Apple, fruit | MK460996 | 100.00 |

| M56 | A. pullulans | Apple, fruit | HQ267772 | 99.63 |

| M57 | A. pullulans | Apple, fruit | KT722604 | 99.26 |

| M69 | A. pullulans | Apple, fruit | MK460995 | 99.27 |

| M87 | A. pullulans | Apple, fruit | MK460996 | 99.63 |

| R01 | A. pullulans | Rosehip, fruit | DQ640765 | 99.09 |

| R05 | A. pullulans | Rosehip, fruit | OR069592 | 99.08 |

| R14 | A. pullulans | Rosehip, fruit | DQ640765 | 99.08 |

| R32 | A. pullulans | Rosehip, fruit | KX444670 | 99.45 |

| R36 | A. pullulans | Rosehip, fruit | MK937951 | 99.63 |

| R43 | A. pullulans | Rosehip, fruit | MK460995 | 99.81 |

| R44 | A. pullulans | Rosehip, fruit | MK460996 | 98.92 |

| R45 | A. pullulans | Rosehip, fruit | MK460995 | 100.00 |

| R52 | A. pullulans | Rosehip, fruit | MN371866 | 99.45 |

| C01 | A. pullulans | Hawthorn, fruit | MK460995 | 99.81 |

| C10 | A. pullulans | Hawthorn, fruit | KT722604 | 99.82 |

| C11 | A. pullulans | Hawthorn, fruit | MT573468 | 99.25 |

| C29 | A. pullulans | Hawthorn, fruit | MT107050 | 99.81 |

| C57 | A. pullulans | Hawthorn, fruit | DQ640765 | 98.37 |

| C61 | A. pullulans | Hawthorn, fruit | MK460995 | 99.81 |

| C66 | A. pullulans | Hawthorn, fruit | OM237133 | 99.62 |

| P05 | A. pullulans | Wild pear, fruit | MT573468 | 99.44 |

| P09 | A. pullulans | Wild pear, fruit | HQ267772 | 99.81 |

| P15 | A. pullulans | Wild pear, fruit | MK937951 | 99.82 |

| P17 | A. pullulans | Wild pear, fruit | MT107050 | 99.81 |

| P61 | A. pullulans | Wild pear, fruit | MK460995 | 99.81 |

| P63 | A. pullulans | Wild pear, fruit | KT722604 | 99.45 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Tulukoğlu-Kunt, K.S.; Özden, M.; Di Francesco, A. Exploring Wild and Local Fruits as Sources of Promising Biocontrol Agents against Alternaria spp. in Apples. Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9101156

Tulukoğlu-Kunt KS, Özden M, Di Francesco A. Exploring Wild and Local Fruits as Sources of Promising Biocontrol Agents against Alternaria spp. in Apples. Horticulturae. 2023; 9(10):1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9101156

Chicago/Turabian StyleTulukoğlu-Kunt, Keziban Sinem, Mustafa Özden, and Alessandra Di Francesco. 2023. "Exploring Wild and Local Fruits as Sources of Promising Biocontrol Agents against Alternaria spp. in Apples" Horticulturae 9, no. 10: 1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9101156

APA StyleTulukoğlu-Kunt, K. S., Özden, M., & Di Francesco, A. (2023). Exploring Wild and Local Fruits as Sources of Promising Biocontrol Agents against Alternaria spp. in Apples. Horticulturae, 9(10), 1156. https://doi.org/10.3390/horticulturae9101156