Recent Advances of Cellulase Immobilization onto Magnetic Nanoparticles: An Update Review

Abstract

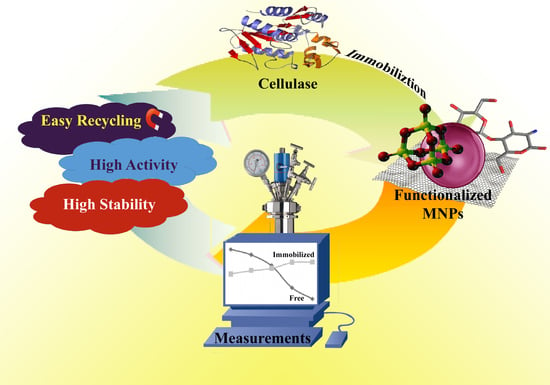

:1. Introduction

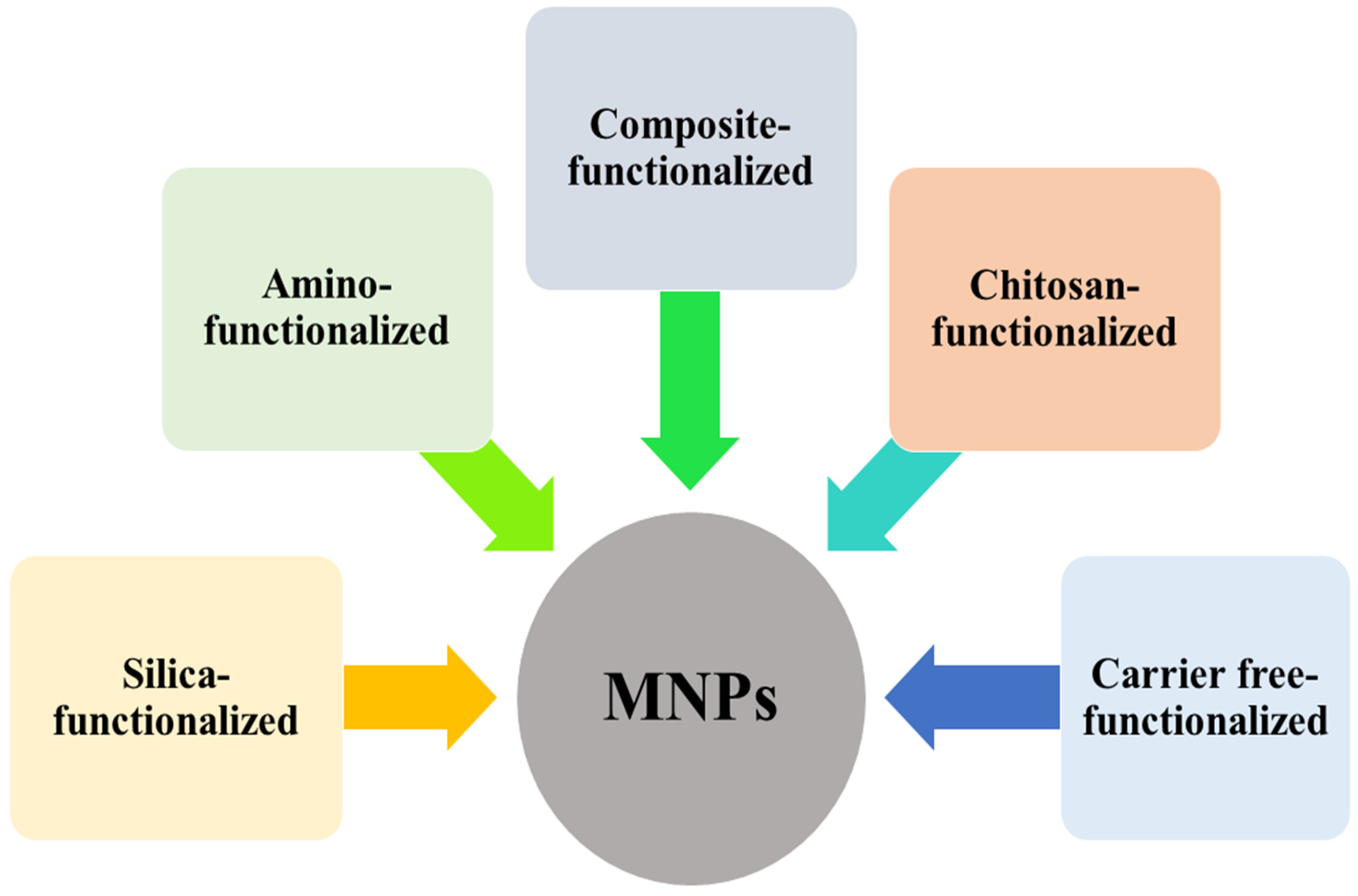

2. Cellulase Immobilization on Silica-Functionalized MNPs

3. Carrier Free Cellulase Immobilization Strategy

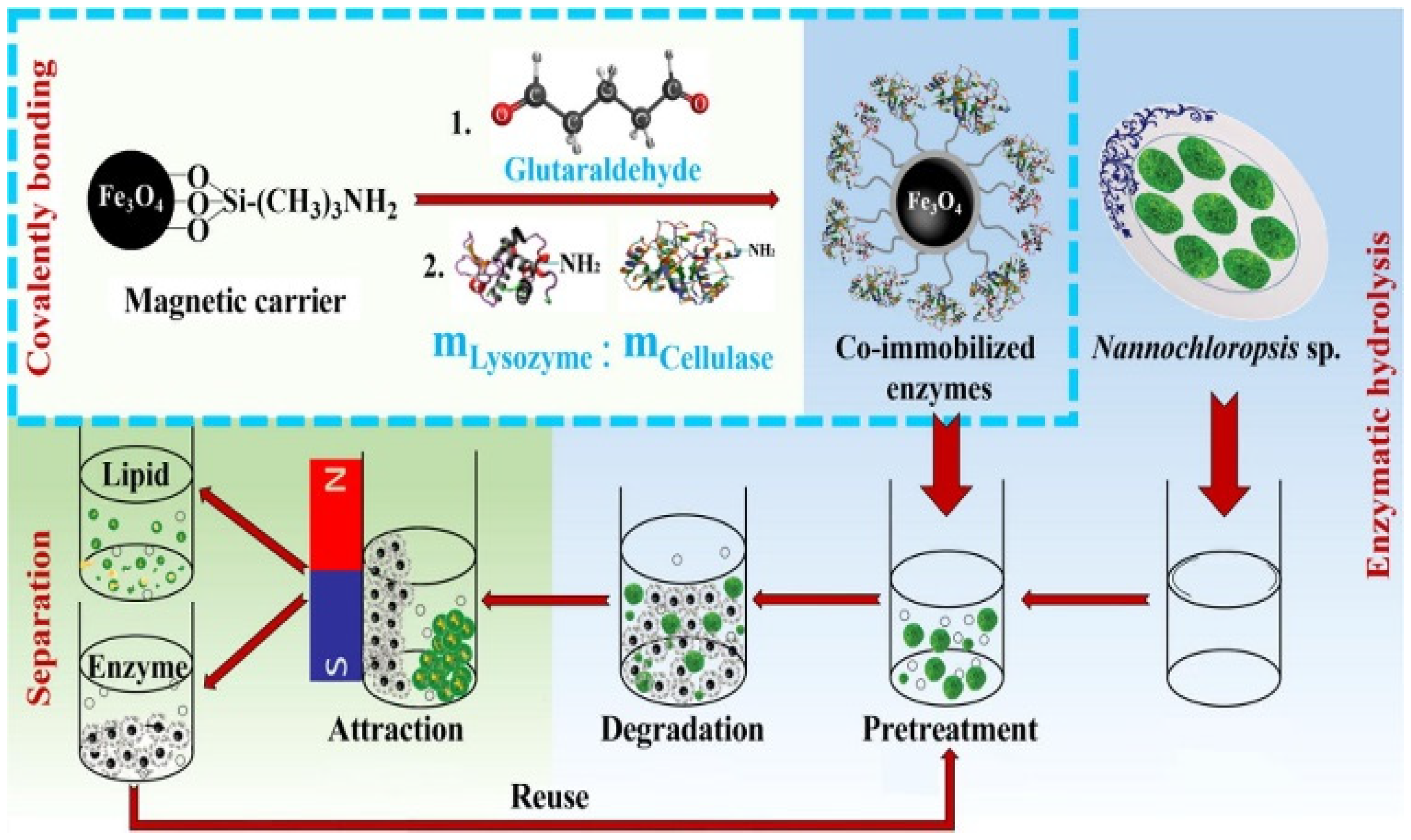

4. Cellulase Immobilization on Amino-Functionalized MNPs

5. Cellulase Immobilization on Composite-Functionalized MNPs

6. Cellulase Immobilization on Chitosan-Functionalized MNPs

7. An Overview of Principal Factors Affecting Cellulase Immobilization onto MNPs

8. Summary and Outlook

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Khoshnevisan, K.; Vakhshiteh, F.; Barkhi, M.; Baharifar, H.; Poor-Akbar, E.; Zari, N.; Stamatis, H.; Bordbar, A.-K. Immobilization of cellulase enzyme onto magnetic nanoparticles: Applications and recent advances. Mol. Catal. 2017, 442, 66–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coseri, S. Cellulose: To depolymerize… or not to? Biotechnol. Adv. 2017, 35, 251–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phitsuwan, P.; Laohakunjit, N.; Kerdchoechuen, O.; Kyu, K.L.; Ratanakhanokchai, K. Present and potential applications of cellulases in agriculture, biotechnology, and bioenergy. Folia Microbiol. 2013, 58, 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kuhad, R.C.; Gupta, R.; Singh, A. Microbial Cellulases and Their Industrial Applications. Enzym. Res. 2011, 2011, 280696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aftab, M.N.; Zafar, A.; Awan, A.R. Expression of thermostable β-xylosidase in Escherichia coli for use in saccharification of plant biomass. Bioengineered 2017, 8, 665–669. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meenu, K.; Singh, G.; Vishwakarma, R.A. Chapter 22—Molecular Mechanism of Cellulase Production Systems in Trichoderma; Gupta, V.K., Schmoll, M., Herrera-Estrella, A., Upadhyay, R.S., Druzhinina, I., Tuohy, M., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 319–324. ISBN 978-0-444-59576-8. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, X.; Arato, C.; Gilkes, N.; Gregg, D.; Mabee, W.; Pye, K.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, X.; Saddler, J. Biorefining of softwoods using ethanol organosolv pulping: Preliminary evaluation of process streams for manufacture of fuel-grade ethanol and co-products. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2005, 90, 473–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein-Marcuschamer, D.; Simmons, B.A.; Blanch, H.W. Techno-economic analysis of a lignocellulosic ethanol biorefinery with ionic liquid pre-treatment. Biofuels Bioprod. Biorefin. 2011, 5, 562–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-H.P.; Ding, S.-Y.; Mielenz, J.R.; Cui, J.-B.; Elander, R.T.; Laser, M.; Himmel, M.E.; McMillan, J.R.; Lynd, L.R. Fractionating recalcitrant lignocellulose at modest reaction conditions. Biotechnol. Bioeng. 2007, 97, 214–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, V.K.; Kubicek, C.P.; Berrin, J.-G.; Wilson, D.W.; Couturier, M.; Berlin, A.; Filho, E.X.F.; Ezeji, T. Fungal Enzymes for Bio-Products from Sustainable and Waste Biomass. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2016, 41, 633–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kossatz, H.L.; Rose, S.H.; Viljoen-Bloom, M.; van Zyl, W.H. Production of ethanol from steam exploded triticale straw in a simultaneous saccharification and fermentation process. Process Biochem. 2017, 53, 10–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binod, P.; Gnansounou, E.; Sindhu, R.; Pandey, A. Enzymes for second generation biofuels: Recent developments and future perspectives. Bioresour. Technol. Rep. 2019, 5, 317–325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poudel, S.; Giannone, R.J.; Rodriguez, M.; Raman, B.; Martin, M.Z.; Engle, N.L.; Mielenz, J.R.; Nookaew, I.; Brown, S.D.; Tschaplinski, T.J.; et al. Integrated omics analyses reveal the details of metabolic adaptation of Clostridium thermocellum to lignocellulose-derived growth inhibitors released during the deconstruction of switchgrass. Biotechnol. Biofuels 2017, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Avanthi, A.; Kumar, S.; Sherpa, K.C.; Banerjee, R. Bioconversion of hemicelluloses of lignocellulosic biomass to ethanol: An attempt to utilize pentose sugars. Biofuels 2017, 8, 431–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheldon, R.A.; Brady, D. The limits to biocatalysis: Pushing the envelope. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 6088–6104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ye, L.; Yang, C.; Yu, H. From molecular engineering to process engineering: Development of high-throughput screening methods in enzyme directed evolution. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 559–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naeem, M.; Rehman, A.U.; Shen, B.; Ye, L.; Yu, H. Semi-rational engineering of carbonyl reductase YueD for efficient biosynthesis of halogenated alcohols with in situ cofactor regeneration. Biochem. Eng. J. 2018, 137, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perwez, M.; Ahmad, R.; Sardar, M. A reusable multipurpose magnetic nanobiocatalyst for industrial applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 103, 16–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muley, A.B.; Thorat, A.S.; Singhal, R.S.; Harinath Babu, K. A tri-enzyme co-immobilized magnetic complex: Process details, kinetics, thermodynamics and applications. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 118, 1781–1795. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waifalkar, P.P.; Parit, S.B.; Chougale, A.D.; Sahoo, S.C.; Patil, P.S.; Patil, P.B. Immobilization of invertase on chitosan coated γ-Fe2O3 magnetic nanoparticles to facilitate magnetic separation. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 482, 159–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dosadina, E.E.; Savelyeva, E.E.; Belov, A.A. The effect of immobilization, drying and storage on the activity of proteinases immobilized on modified cellulose and chitosan. Process Biochem. 2018, 64, 213–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Rasheed, T.; Zhao, Y.; Iqbal, H.M.N.; Cui, J. “Smart” chemistry and its application in peroxidase immobilization using different support materials. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 119, 278–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, D.-M.; Chen, J.; Shi, Y.-P. Advances on methods and easy separated support materials for enzymes immobilization. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2018, 102, 332–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lonappan, L.; Liu, Y.; Rouissi, T.; Pourcel, F.; Brar, S.K.; Verma, M.; Surampalli, R.Y. Covalent immobilization of laccase on citric acid functionalized micro-biochars derived from different feedstock and removal of diclofenac. Chem. Eng. J. 2018, 351, 985–994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaak, H.; Sassi, M.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R. A new heterofunctional amino-vinyl sulfone support to immobilize enzymes: Application to the stabilization of β-galactosidase from Aspergillus oryzae. Process Biochem. 2018, 64, 200–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaghari, H.; Jafarizadeh-Malmiri, H.; Mohammadlou, M.; Berenjian, A.; Anarjan, N.; Jafari, N.; Nasiri, S. Application of magnetic nanoparticles in smart enzyme immobilization. Biotechnol. Lett. 2016, 38, 223–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Royvaran, M.; Taheri-Kafrani, A.; Landarani Isfahani, A.; Mohammadi, S. Functionalized superparamagnetic graphene oxide nanosheet in enzyme engineering: A highly dispersive, stable and robust biocatalyst. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 288, 414–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baharifar, H.; Honarvarfard, E.; Haji Malek-kheili, M.; Maleki, H.; Barkhi, M.; Ghasemzadeh, A.; Khoshnevisan, K. The Potentials and Applications of Cellulose Acetate in biosensor technology. Nanomed. Res. J. 2017, 2, 216–223. [Google Scholar]

- Khoshnevisan, K.; Maleki, H.; Honarvarfard, E.; Baharifar, H.; Gholami, M.; Faridbod, F.; Larijani, B.; Faridi Majidi, R.; Khorramizadeh, M.R. Nanomaterial based electrochemical sensing of the biomarker serotonin: A comprehensive review. Microchim. Acta 2019, 186, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zeng, G.; Xu, P.; Lai, C.; Tang, L. How Do Enzymes ‘Meet’ Nanoparticles and Nanomaterials? Trends Biochem. Sci. 2017, 42, 914–930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasir, M.; Nawaz, M.H.; Latif, U.; Yaqub, M.; Hayat, A.; Rahim, A. An overview on enzyme-mimicking nanomaterials for use in electrochemical and optical assays. Microchim. Acta 2017, 184, 323–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, Q.; Lou, Z.; Li, S.; Zhu, Y.; Qin, L.; Wei, H. Nanomaterials with enzyme-like characteristics (nanozymes): Next-generation artificial enzymes (II). Chem. Soc. Rev. 2019, 48, 1004–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hemmati, M.; Barkhi, M.; Baharifar, H.; Khoshnevisan, K. Removal of Malachite Green by Using Immobilized Glucose Oxidase Onto Silica Nanostructure-Coated Silver Metal-Foam. J. Nanoanal. 2017, 4, 196–204. [Google Scholar]

- Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Chemical, physical, and biological coordination: An interplay between materials and enzymes as potential platforms for immobilization. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2019, 388, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pandiyaraj, K.N.; Ramkumar, M.C.; Arun Kumar, A.; Padmanabhan, P.V.A.; Pichumani, M.; Bendavid, A.; Cools, P.; De Geyter, N.; Morent, R.; Kumar, V.; et al. Evaluation of surface properties of low density polyethylene (LDPE) films tailored by atmospheric pressure non-thermal plasma (APNTP) assisted co-polymerization and immobilization of chitosan for improvement of antifouling properties. Mater. Sci. Eng. C 2019, 94, 150–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tedersoo, L.; Sánchez-Ramírez, S.; Kõljalg, U.; Bahram, M.; Döring, M.; Schigel, D.; May, T.; Ryberg, M.; Abarenkov, K. High-level classification of the Fungi and a tool for evolutionary ecological analyses. Fungal Divers. 2018, 90, 135–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez-Ramírez, J.; Martínez-Hernández, J.L.; Segura-Ceniceros, P.; López, G.; Saade, H.; Medina-Morales, M.A.; Ramos-González, R.; Aguilar, C.N.; Ilyina, A. Cellulases immobilization on chitosan-coated magnetic nanoparticles: Application for Agave Atrovirens lignocellulosic biomass hydrolysis. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 40, 9–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, J.; Xiong, P.; He, B. Advances in improving the performance of cellulase in ionic liquids for lignocellulose biorefinery. Bioresour. Technol. 2016, 200, 961–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cipolatti, E.P.; Valério, A.; Henriques, R.O.; Moritz, D.E.; Ninow, J.L.; Freire, D.M.G.; Manoel, E.A.; Fernandez-Lafuente, R.; de Oliveira, D. Nanomaterials for biocatalyst immobilization—State of the art and future trends. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 104675–104692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malgas, S.; Thoresen, M.; van Dyk, J.S.; Pletschke, B.I. Time dependence of enzyme synergism during the degradation of model and natural lignocellulosic substrates. Enzym. Microb. Technol. 2017, 103, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina, G.; de Lima, E.A.; Borin, G.P.; de Barcelos, M.C.S.; Pastore, G.M. Chapter 7—Beta-Glucosidase From Penicillium; Gupta, V.K., Rodriguez-Couto, S.B.T.-N., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2018; pp. 137–151. ISBN 978-0-444-63501-3. [Google Scholar]

- Khoshnevisan, K.; Bordbar, A.-K.; Zare, D.; Davoodi, D.; Noruzi, M.; Barkhi, M.; Tabatabaei, M. Immobilization of cellulase enzyme on superparamagnetic nanoparticles and determination of its activity and stability. Chem. Eng. J. 2011, 171, 669–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnevisan, K.; Barkhi, M.; Zare, D.; Davoodi, D.; Tabatabaei, M. Preparation and Characterization of CTAB-Coated Fe3O4 Nanoparticles. Synth. React. Inorg. Met. Org. Nano-Met. Chem. 2012, 42, 644–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoshnevisan, K.; Barkhi, M.; Ghasemzadeh, A.; Tahami, H.V.; Pourmand, S. Fabrication of Coated/Uncoated Magnetic Nanoparticles to Determine Their Surface Properties. Mater. Manuf. Process. 2016, 31, 1206–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Wang, L.; Wang, Y.; Dong, J.; Tang, X.; Ni, L.; Wang, L. Preparation and characterization of Fe3O4-NH2@4-arm-PEG-NH2, a novel magnetic four-arm polymer-nanoparticle composite for cellulase immobilization. Biochem. Eng. J. 2018, 130, 90–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Y.; Liu, X.; Xing, Z.; Geng, Y.; Wilson, J.; Wu, D.; Kong, H. Preparation and characterization of magnetic Fe3O4–chitosan nanoparticles for cellulase immobilization. Cellulose 2017, 24, 5541–5550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.; Mo, H.; Zang, L.; Chen, J.; Wang, Z.; Qiu, J. Surface functionalized natural inorganic nanorod for highly efficient cellulase immobilization. RSC Adv. 2016, 6, 76855–76860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zang, L.; Qiao, X.; Hu, L.; Yang, C.; Liu, Q.; Wei, C.; Qiu, J.; Mo, H.; Song, G.; Yang, J.; et al. Preparation and Evaluation of Coal Fly Ash/Chitosan Composites as Magnetic Supports for Highly Efficient Cellulase Immobilization and Cellulose Bioconversion. Polymers 2018, 10, 523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carli, S.; de Campos Carneiro, L.A.B.; Ward, R.J.; Meleiro, L.P. Immobilization of a β-glucosidase and an endoglucanase in ferromagnetic nanoparticles: A study of synergistic effects. Protein Expr. Purif. 2019, 160, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacicedo, M.L.; Manzo, R.M.; Municoy, S.; Bonazza, H.L.; Islan, G.A.; Desimone, M.; Bellino, M.; Mammarella, E.J.; Castro, G.R. Chapter 7—Immobilized Enzymes and Their Applications. In Biomass, Biofuels, Biochemicals; Singh, R.S., Singhania, R.R., Pandey, A., Larroche, C.B.T.-A., Eds.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; pp. 169–200. ISBN 978-0-444-64114-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Jin, P.; Liu, M.; Pan, J.; Yan, Y.; Chen, Y.; Xiong, Q. A novel route for green conversion of cellulose to HMF by cascading enzymatic and chemical reactions. AIChE J. 2017, 63, 4920–4932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, J.; Ahmad, R.; Khare, S.K. Development of cellulase-nanoconjugates with enhanced ionic liquid and thermal stability for in situ lignocellulose saccharification. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 242, 236–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, S.; Tiwari, R.; Goel, R.; Nain, L. Immobilization of indigenous holocellulase on iron oxide (Fe2O3) nanoparticles enhanced hydrolysis of alkali pretreated paddy straw. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 96, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Zhang, W.; Yang, Z.; Yang, X.; Wang, N.; Yu, X. Novel Magnetic Cross-Linked Cellulase Aggregates with a Potential Application in Lignocellulosic Biomass Bioconversion. Molecules 2017, 22, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaikwad, S.; Ingle, A.P.; da Silva, S.S.; Rai, M. Immobilized Nanoparticles-Mediated Enzymatic Hydrolysis of Cellulose for Clean Sugar Production: A Novel Approach. Curr. Nanosci. 2019, 15, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.D.; Jia, S.R. Optimization protocols and improved strategies of cross-linked enzyme aggregates technology: Current development and future challenges. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2015, 35, 15–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, M.-Q.; Wang, S.-S.; Li, L.-N.; Gao, J.; Zhang, Y.-W. Combined Cross-Linked Enzyme Aggregates as Biocatalysts. Catalysts 2018, 8, 460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilal, M.; Asgher, M.; Parra-Saldivar, R.; Hu, H.; Wang, W.; Zhang, X.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Immobilized ligninolytic enzymes: An innovative and environmental responsive technology to tackle dye-based industrial pollutants—A review. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 576, 646–659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jafari Khorshidi, K.; Lenjannezhadian, H.; Jamalan, M.; Zeinali, M. Preparation and characterization of nanomagnetic cross-linked cellulase aggregates for cellulose bioconversion. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2016, 91, 539–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, A.; Kaila, P.; Tiwari, P.; Singh, V.; Kaul, S.; Singhal, N.; Guptasarma, P. Multiple thermostable enzyme hydrolases on magnetic nanoparticles: An immobilized enzyme-mediated approach to saccharification through simultaneous xylanase, cellulase and amylolytic glucanotransferase action. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 120, 1650–1658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwaminger, S.P.; Fraga-García, P.; Selbach, F.; Hein, F.G.; Fuß, E.C.; Surya, R.; Roth, H.-C.; Blank-Shim, S.A.; Wagner, F.E.; Heissler, S.; et al. Bio-nano interactions: Cellulase on iron oxide nanoparticle surfaces. Adsorption 2017, 23, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingle, A.P.; Rathod, J.; Pandit, R.; da Silva, S.S.; Rai, M. Comparative evaluation of free and immobilized cellulase for enzymatic hydrolysis of lignocellulosic biomass for sustainable bioethanol production. Cellulose 2017, 24, 5529–5540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadar, S.S.; Rathod, V.K. A co-immobilization of pectinase and cellulase onto magnetic nanoparticles for antioxidant extraction from waste fruit peels. Biocatal. Agric. Biotechnol. 2019, 17, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladole, M.R.; Nair, R.R.; Bhutada, Y.D.; Amritkar, V.D.; Pandit, A.B. Synergistic effect of ultrasonication and co-immobilized enzymes on tomato peels for lycopene extraction. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2018, 48, 453–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ladole, M.R.; Mevada, J.S.; Pandit, A.B. Ultrasonic hyperactivation of cellulase immobilized on magnetic nanoparticles. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 239, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Q.; Liu, D.; Wu, C.; Yao, K.; Li, Z.; Shi, N.; Wen, F.; Gates, I.D. Co-immobilization of cellulase and lysozyme on amino-functionalized magnetic nanoparticles: An activity-tunable biocatalyst for extraction of lipids from microalgae. Bioresour. Technol. 2018, 263, 317–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abbaszadeh, M.; Hejazi, P. Metal affinity immobilization of cellulase on Fe3O4 nanoparticles with copper as ligand for biocatalytic applications. Food Chem. 2019, 290, 47–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pei, J.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Yuan, H.; Liu, X.; Ni, C. A Novel Layered Anchoring Structure Immobilized Cellulase via Covalent Binding of Cellulase on MNPs Anchored by LDHs. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym. Mater. 2018, 28, 1624–1635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velmurugan, R.; Incharoensakdi, A. MgO-Fe3O4 linked cellulase enzyme complex improves the hydrolysis of cellulose from Chlorella sp. CYB2. Biochem. Eng. J. 2017, 122, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lima, J.S.; Araújo, P.H.H.; Sayer, C.; Souza, A.A.U.; Viegas, A.C.; de Oliveira, D. Cellulase immobilization on magnetic nanoparticles encapsulated in polymer nanospheres. Bioprocess Biosyst. Eng. 2017, 40, 511–518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J.; Luo, P.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Zhang, W.; Dong, J.; Ni, L. The development of nanobiocatalysis via the immobilization of cellulase on composite magnetic nanomaterial for enhanced loading capacity and catalytic activity. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 119, 692–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

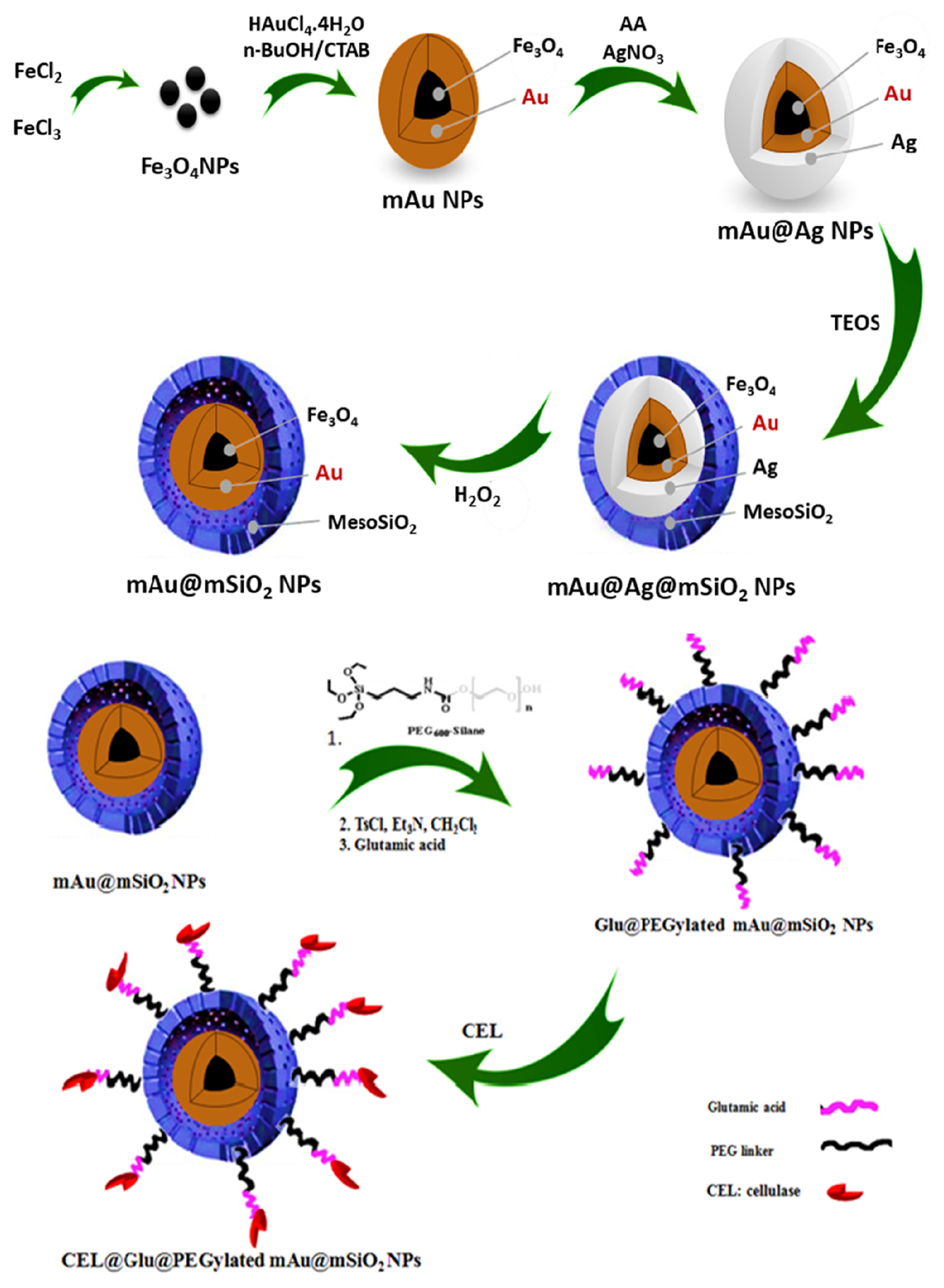

- Poorakbar, E.; Shafiee, A.; Saboury, A.A.; Rad, B.L.; Khoshnevisan, K.; Ma’mani, L.; Derakhshankhah, H.; Ganjali, M.R.; Hosseini, M. Synthesis of magnetic gold mesoporous silica nanoparticles core shell for cellulase enzyme immobilization: Improvement of enzymatic activity and thermal stability. Process Biochem. 2018, 71, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Díaz-Hernández, A.; Gracida, J.; García-Almendárez, B.E.; Regalado, C.; Núñez, R.; Amaro-Reyes, A. Characterization of Magnetic Nanoparticles Coated with Chitosan: A Potential Approach for Enzyme Immobilization. J. Nanomater. 2018, 2018, 9468574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sánchez-Ramírez, J.; Martínez-Hernández, J.L.; López-Campos, R.G.; Segura-Ceniceros, E.P.; Saade, H.; Ramos-González, R.; Neira-Velázquez, M.G.; Medina-Morales, M.A.; Aguilar, C.N.; Ilyina, A. Laccase Validation as Pretreatment of Agave Waste Prior to Saccharification: Free and Immobilized in Superparamagnetic Nanoparticles Enzyme Preparations. Waste Biomass Valorization 2018, 9, 223–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Ju, X.; Li, L.; Yan, L.; Xu, X.; Chen, J. Immobilization of cellulase in the non-natural ionic liquid environments to enhance cellulase activity and functional stability. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2019, 103, 2483–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saha, K.; Verma, P.; Sikder, J.; Chakraborty, S.; Curcio, S. Synthesis of chitosan-cellulase nanohybrid and immobilization on alginate beads for hydrolysis of ionic liquid pretreated sugarcane bagasse. Renew. Energy 2019, 133, 66–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohara, R.A.; Thorat, N.D.; Pawar, S.H. Immobilization of cellulase on functionalized cobalt ferrite nanoparticles. Korean J. Chem. Eng. 2016, 33, 216–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Enzyme | Substrate | Support | Coupling Agent | Amount * | pH | Temperature | Reusability | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle | Efficiency | ||||||||

| Pectinase Xylanase Cellulase | Polygalacturonic acid Xylan CMC | (Fe3O4) on APTES | Glutaraldehyde | 12, 5, 31 mg/mL | 4.8 | 70 °C | 5 | 87%, 69%, and 58% | [18] |

| Cellulase | Cellulose | Fe3O4 encapsulated with SBA-15 | PEG-1000 | 1.6 mg | 4.8 | 25–85 °C | 5 | 87.5% | [51] |

| Cellulase | Wheat straw and sugarcane | [EMIM][Ac] functionalized-MNPs and SNP | Glutaraldehyde | 10 and, 7.5 mg/mL | 3.5–9.5 | 20–80 °C | 10 | 85% and 76% | [52] |

| Holocellulase | FP, CMC, and xylan | APTES-Fe3O4 | Glutaraldehyde | 2 mg/mL | 3–7 | 40–80 °C | 2 | 60–80% | [53] |

| Cellulase | CMC | APTES-Fe3O4 | Glutaraldehyde | 176 mg/g | 3–8 | 30–80 °C | 6 | 88% | [54] |

| Enzyme | Substrate | Support | Coupling Agent | Amount | pH | Temperature | Reusability | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle | Efficiency | ||||||||

| Cellulase, pectinase, and xylanase | CMC, pectin, and xylan | Fe3O4 | Glutaraldehyde | 5.06 ± 0.46 mg/mL 3.39 ± 0.12 mg/mL 2.95 ± 0.14 mg/mL | 5.5 | 55–75 °C | 4 | 80.25 ± 1.03% 84.76 ± 1.71% 75.62 ± 0.76% | [19] |

| Xylanase, cellulase, amylase | Xylan, CMC, starch | MNPs | Glutaraldehyde | 3 mg/mL | 2–12 | Thermostable up to 70 °C | 13 | 69, 48, and 50% | [60] |

| Cellulase | N/A * | magnetite, maghemite, and hematite MNPs | N/A | 0.6 g∙g−1 | N/A | NA | N/A | N/A | [61] |

| Cellulase | Microcrystalline | Fe3O4 | Glutaraldehyde | 250 mg | N/A | 27 °C, 40 °C, 50 °C and 60 °C | 3 | 52% | [62] |

| Enzyme | Substrate | Support | Coupling Agent | Amount | pH | Temperature | Reusability | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle | Efficiency | ||||||||

| Pectinase, cellulase | Carboxymethyl cellulose (CMC) | AMNPs | Glutaraldehyde | 9 and 3 mg/mL | 6.5 | 50–70 °C | 8 | 87% and 82% | [63] |

| Pectinase, cellulase | pectin, cellulose | AMNPs | Glutaraldehyde | 50 mg | 5 | 25–35 °C | 8 | 85% and 80% | [64] |

| Cellulase | cellulose | AMNPs | Glutaraldehyde | N/A | 3–8 | 30–80 °C | 7 | 58% | [65] |

| Cellulase, lysozyme | cell walls | AMNPs | Glutaraldehyde | 0.5 mg | 3–7 | 60–80 °C | 6 | 78.1% and 69.6% | [66] |

| Cellulase | CMC | Cu/AMNPs | APTES | N/A | 2–7 | 20–80 °C | 5 | 73% | [67] |

| Enzyme | Substrate | Support | Coupling Agent | Amount | pH | Temperature | Reusability | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle | Efficiency | ||||||||

| Cellulase | CMC | (Fe3O4) layered double hydroxides (LDHs) | Glutaraldehyde | 1.2 g/L | 5.5 | 50 °C | 6 | 31.8% | [68] |

| Cellulase | cellulose | MgO–Fe3O4 | Xylan aldehyde | 150 mg/g | 4.5–6.5 | 50–70 °C | 7 | 84.5% | [69] |

| Cellulase | CMC | Poly(methyl methacrylate) MNPs | N/A | 5% (w/v) | 3–8 | 35–75 °C | 8 | 69% | [70] |

| Cellulase | Microcrystalline cellulose or filter paper | Fe3O4-NH2@4-arm-PEG-NH2 | Glutaraldehyde | 132 mg/g | 3–7 | 30–80 °C | 6 | 76%. | [45] |

| Cellulase | Microcrystalline cellulose or filter paper | GO@Fe3O4@4arm PEG NH2 | Glutaraldehyde | 2–8 mg | 3.5–5.5 | 30–80 °C | 7 | 65% and 70% | [71] |

| Cellulase | Microcrystalline or filter paper | Glu@PEGylated mAu@PSN | Glutamic acid | 25 mg | 3–8 | 35–75 °C | 5 | 76% | [72] |

| Enzyme | Substrate | Support | Coupling Agent | Amount | pH | Temperature | Reusability | Ref. | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cycle | Efficiency | ||||||||

| Cellulase | CMC | Chitosan-coated MNPs (Ch-MNPs) | Glutaraldehyde | 26.06 mg | 2.5–8.5 | 20–70 °C | 15 | 80% | [37] |

| Cellulase | CMC | Magnetic Fe3O4−chitosan | Glutaraldehyde | 32.29 mg | 3–7 | 30–70 °C | 5 | 80% | [46] |

| Xylanase and cellulase 1:0.5 | N/A | Chitosan-coated magnetite particles | Glutaraldehyde | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | [73] |

| Laccase | Lignin | Chitosan (C)-MNP | Glutaraldehyde | 25 mg | 2–7 | 25–75 °C | 5 | 50% | [74] |

| Different Functionalized MNPs Applied in Cellulase Immobilization Approaches | ||

|---|---|---|

| Immobilization Approach | Attributes | Ref. |

| Silica-based surface functionalization | Enhanced chemical stability while avoiding the aggregation of nanoparticles | [51,52,53,54] |

| Composite-based surface functionalization | Providing unique physical and electronic properties and also providing a large surface area for biomolecules to anchor | [69,70,71,72] |

| Amino-based surface functionalization | Novel strategies to enhance the enzyme’s thermal and chemical stability | [63,64,65,66,67] |

| Chitosan-based surface functionalization | Providing an appropriate surface for biomolecules to anchor | [46,74] |

| Carrier-free immobilization | Novel strategies to improve enzyme activity | [60,61,62] |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Khoshnevisan, K.; Poorakbar, E.; Baharifar, H.; Barkhi, M. Recent Advances of Cellulase Immobilization onto Magnetic Nanoparticles: An Update Review. Magnetochemistry 2019, 5, 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry5020036

Khoshnevisan K, Poorakbar E, Baharifar H, Barkhi M. Recent Advances of Cellulase Immobilization onto Magnetic Nanoparticles: An Update Review. Magnetochemistry. 2019; 5(2):36. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry5020036

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhoshnevisan, Kamyar, Elahe Poorakbar, Hadi Baharifar, and Mohammad Barkhi. 2019. "Recent Advances of Cellulase Immobilization onto Magnetic Nanoparticles: An Update Review" Magnetochemistry 5, no. 2: 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry5020036

APA StyleKhoshnevisan, K., Poorakbar, E., Baharifar, H., & Barkhi, M. (2019). Recent Advances of Cellulase Immobilization onto Magnetic Nanoparticles: An Update Review. Magnetochemistry, 5(2), 36. https://doi.org/10.3390/magnetochemistry5020036