3.1. Role of APTES in the Synthesis of SiO2@Si Shells

SEM images of TEOS- and APTES/TEOS-derived SiO

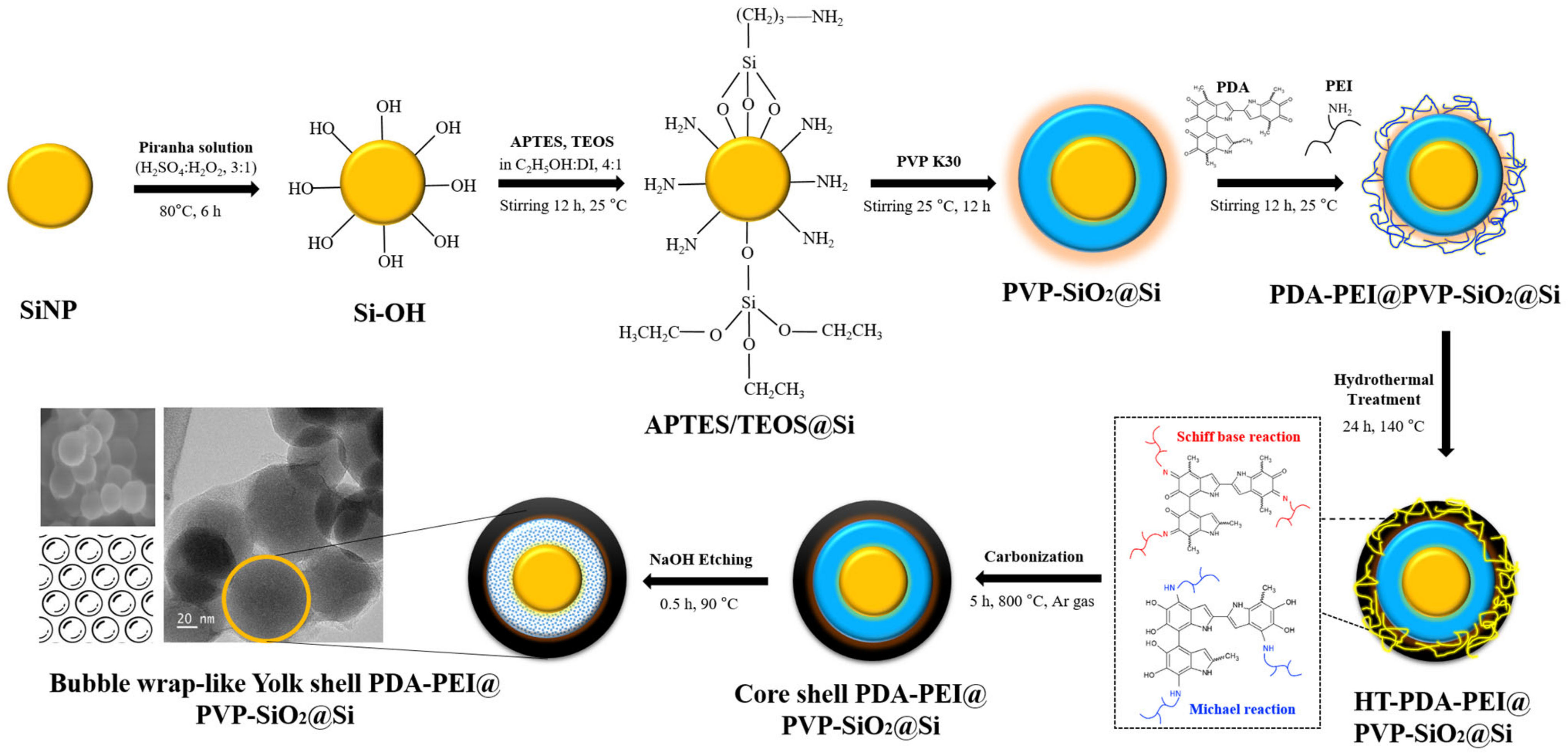

2 shells precursors are shown in

Figure 2.

The FE-SEM image and FT-IR spectra of Si following piranha pre-treatment are illustrated in

Figure S1 (Supplementary Materials).

Figure 2a displays a non-uniform, thick coating of TEOS-derived SiO

2 shell on Si, while

Figure 2b exhibits a more uniform SiO

2 coating with reduced Si–OH nanoparticle agglomeration in the APTES/TEOS-derived SiO

2. Notably, a conformal spherical morphology with an average particle diameter of ~60 nm was observed, attributed to APTES’s self-catalytic activity in sol-gel SiO

2 particle formation, fostering siloxane bond formation with abundant silanol groups on Si–OH, even without the presence of an alkali catalyst [

55].

Supporting evidence for APTES’s self-catalyzing role in promoting SiO

2 growth and effective coating on Si–OH is furnished by TEM results, as depicted in

Figure 3.

Figure 3a exhibits notable particle agglomeration of TEOS–SiO

2@Si without discernible structural organization. In

Figure 3b, an isolated TEOS–SiO

2@Si particle features a ~50 nm Si nanoparticle enveloped by a thick SiO

2 coating, displaying evident aggregation with dark patches in the background. The in-plane lattice fringe, highlighted in

Figure 3c, reveals a 0.3096 nm ordered lattice spacing attributed to the (111) plane of Si [

37]. The inset in

Figure 3d displays a corresponding fast Fourier transform (FFT) pattern, confirming sustained Si crystallinity following the SiO

2 sol-gel coating process using TEOS.

Figure 3e highlights APTES’s role as a structure-directing agent, depicting APTES/TEOS-derived SiO

2@Si with an absence of visible particle aggregation and a uniform spherical morphology.

Figure 3f illustrates an isolated APTES/TEOS–SiO

2@Si nanoparticle with a thin, conformal SiO

2 coating (~8 nm). Two distinct crystal lattice spacings, observed in

Figure 3g (0.3112 nm and 0.1993 nm), align well with the (111) and (220) planes of Si, respectively [

31,

37]. The inset image in

Figure 3h displays notable bright spots, affirming the preserved crystallinity of Si during the SiO

2 sol-gel coating process using APTES.

Prior works on the co-condensation of TEOS and APTES in EtOH and DI have predominantly utilized APTES as a surface modifier in post-modification or grafting scenarios to introduce amino groups to Si [

35]. This application extends to APTES serving as a precursor material to SiO

2 [

55], often employed in soft–hard template strategies utilizing other surfactants, like cetyl trimethyl ammonium bromide (CTAB) [

58]. To illustrate the pivotal function of APTES as a self-catalytic, structure-directing agent in conjunction with TEOS, the hydrolysis and condensation reaction mechanism and the formation of siloxane networks from APTES and TEOS are detailed in

Figure S2 (Supplementary Materials).

The choice of APTES and TEOS for synthesizing SiO2 shells is guided by the unique properties and functionalities introduced by APTES into the SiO2 matrix. In the conventional Stöber process, TEOS undergoes slow hydrolysis and condensation, necessitating extended reaction times for SiO2 formation. Additionally, the condensation of TEOS into siloxane networks requires a potent base catalyst. Furthermore, employing TEOS with a base catalyst offers limited control over particle size, growth, and morphology. Factors such as temperature, rotations per minute, and pH level influence reaction conditions. Achieving uniform particle size with TEOS is challenging, as incomplete control over synthesis conditions may yield a broad distribution of particle sizes.

Prior investigations have elucidated the self-catalytic mechanism inherent to APTES. In a co-condensation modification utilizing APTES and TEOS, the Stöber route yielded highly monodispersed, ~60 nm-modified nanosilica particles [

59]. The self-catalytic role of APTES was also explored in atomic layer deposition (ALD) for SiO

2 from APTES, water, and ozone gas [

60]. Another study employing APTES as the sole SiO

2 precursor in simultaneous condensation copolymerization with ascorbic acid resulted in a crosslinked carbon matrix reinforced by dispersed nano-SiO

2, further suggesting APTES’s self-catalysis into SiO

2 shells after mechanical stirring at 60 °C for 8 h [

55]. The intricate reaction mechanism underlying APTES’s self-catalytic activity is expounded in

Figure S2a (Supplementary Materials).

It is important to highlight that while pristine Si nanoparticles inherently acquire a native oxide layer due to unavoidable surface oxidation during manufacturing, treating them with piranha solution is generally preferred. This treatment optimizes the number of surface hydroxyl groups, facilitating bond formation with the silanol groups of APTES and TEOS. The –OH groups resulting from piranha pre-treatment on Si–OH energetically promote siloxane bond formation in a condensation reaction, leading to a well-ordered silane layer on the Si surface within APTES/TEOS, even in the absence of alkali catalysts.

XPS analysis was conducted to confirm elemental composition changes during SiO

2 synthesis from two precursors and subsequent coating onto Si nanoparticles, as depicted in

Figure 4. The survey spectra of SiO

2 shells derived from the two precursors are compared in

Figure S3. High-resolution Si 2p spectra of TEOS-derived SiO

2@Si revealed peaks at 102.71 eV (Si–O–Si), 100.59 eV (Si–OH), and a small peak at 98.86 eV (Si). O 1s scans displayed peaks at 531.98 eV (Si–O–Si) and 530.67 eV (Si–OH). These findings indicated the successful conversion of the majority of TEOS silane precursor into SiO

2, with trace Si–OH potentially originating from unreacted hydroxyl groups. The presence of a small Si peak suggested inefficient coating, leaving some Si nanoparticles bare. C 1s spectra highlighted different carbon environments within TEOS organic groups. O 1s peaks at 532.59 eV (O–C=O) and 533.99 eV (O–C=O) revealed the distinct bonding environments of O atoms in ester groups [

61,

62].

In Si 2p scans of APTES/TEOS-derived SiO

2@Si nanoparticles (

Figure 4d), Si–OH and pure Si peaks were absent, signifying the successful condensation of all Si–OH into a SiO

2 layer. Si 2p scans revealed a relatively high-intensity shift of the Si–O–Si peak to a higher binding energy of 105.04 eV, attributed to a particle charge on the deposited SiO

2 coating. This shift, observed in silicon oxides, differed from non-oxidized species that exhibited no shift [

61,

63]. The Si 2p peak at 105.04 eV indicated Si in the 4

+ oxidation state, while broad peaks at 103.27 eV and 105.83 eV were assigned to Si

2+ and Si

3+ oxidation states of amorphous SiO

x, respectively [

64]. The small peak of Si–OH at 101.84 eV further supported SiO

2 coating construction. The O 1s peaks (

Figure 4e) at 532.17 eV (C–O–Si), 531.22 eV (N–C=O), and 534.11 eV (O–C=O) aligned with C 1s scans (

Figure 4f), corroborating successful amino-functionalized SiO

2 modification from APTES [

65]. A negligible peak at 536 eV was attributed to trace amounts of adsorbed H

2O molecules during sample analysis [

66]. Furthermore, N 1s peaks at 401.51 eV, ascribing to C–N, confirmed the effective SiO

2 modification into an amino-functionalized SiO

2 coating due to the chemical compositions of APTES [

65].

3.3. Significance of PVP K30 Surface Protection during NaOH Etching

Chemical bonds in composite samples throughout the fabrication process were analyzed to assess direct PVP K30 loading. Successful loading was confirmed via FTIR analysis, as depicted in

Figure 7.

The initial detection of abundant surface –OH groups around ~3400 cm

−1, subsequent to piranha pre-treatment, vanished entirely in the spectra of all samples. This disappearance indicates the successful condensation reactions of APTES/TEOS. The adsorption band at 1544 cm

−1, corresponding to –NH

2 groups from the APTES precursor solution, remained evident. A weak absorption band at 1348 cm

−1, attributed to C–H bending vibrations of unhydrolyzed –OEt groups, was identified in APTES/TEOS–SiO

2@Si. Its intensity diminished further upon loading PVP K30 to produce PVP–SiO

2@Si, suggesting hydrogen bond formation with the SiO

2 surface. Additional peaks at 2925 cm

−1 (–CH

2 stretching modes in the pyrrolidone ring), 1703 cm

−1 (C=O stretching band), and 1645 cm

−1 (C=C bond in the PVP polymer backbone) provided further evidence of successful PVP loading into SiO

2 shells [

56]. The increased C=C peak is attributed to the formation of a graphitic carbon structure during hydrothermal treatment, resulting from polymerization and crosslinking reactions of PDA and PEI polymers. Moreover, a broad and intense absorption band spanning 788–1095 cm

−1 (highlighted in yellow in

Figure 7), corresponding to symmetric and asymmetric stretching of Si–O–Si bands, and a Si–OH peak at 947 cm

−1 present in all samples further affirmed the complete condensation of the APTES/TEOS precursor and the formation of the SiO

2 shell [

44,

56].

The reaction mechanism between the chosen PVP K30 molecules and the synthesized SiO2 shells involves a combination of physical adsorption and chemical bonding. PVP, a water-soluble polymer, typically undergoes adsorption on the SiO2 surface through hydrogen bonding and Van der Waals forces in an aqueous environment. The oxygen atoms in the pyrrolidone ring of PVP K30 readily form hydrogen bonds with the hydroxyl groups on piranha-treated Si–OH, subsequently coated with SiO2 from APTES and TEOS condensation. PVP K30 proves advantageous in preventing Ostwald ripening in high-surface energy SiO2 nanoparticles. The hydrothermal treatment employed in this study promotes chemical bonding between PVP K30 and SiO2 shells, as verified by FT-IR results, where oxygen atoms of the pyrrolidone ring form coordination bonds with the surface silanol groups of APTES/TEOS–SiO2@Si.

It is noteworthy that the Si–O–Si band intensity exhibited a declining trend from sol-gel coating to etching. The initial decrease, upon the addition of PVP K30, was attributed to the formation of PVP-treated SiO2 shells. Subsequent reduction in peak intensity occurred with the introduction of PDA–PEI, coinciding with the emergence of a robust C=C peak. Thermal treatment at 800 °C contributed to increased SiO2 stability, evidenced by a slight increase in Si–O–Si band intensity. Eventually, a significant reduction in Si–O–Si band intensity ensued after NaOH etching, signifying the dissolution of the SiO2 template.

TEM analysis, depicted in

Figure 8, contrasts sample composites with and without PVP K30 surface protection, emphasizing carbon coating integrity and the preservation of spherical morphologies post-etching. As illustrated in

Figure 8a,b, PVP K30 surface-protected composite samples exhibited exceptional stability, sustaining the PDA–PEI carbon network structure even after NaOH etching. In contrast,

Figure 8c,d illustrates distinct morphological differences in composites lacking PVP K30 protection, where a substantial portion of PDA carbon shells was compromised, and sheet-like PEI carbon networks were disrupted.

The confirmation of PVP K30 polymer loading into APTES/TEOS–SiO

2@Si was established through XPS analysis, as depicted in

Figure 9. The survey spectra of PVP–SiO

2@Si were compared with pristine Si nanoparticles (

Figure S7 in Supplementary Materials). High-resolution Si 2p scans (

Figure 9a) exhibited peaks at 104.11 eV, 102.75 eV, and 105.09 eV, corresponding to the Si–O–Si band. Si oxidation states (Si

2+, Si

3+, Si

4+) indicated SiO

2 shell synthesis after APTES and TEOS condensation [

61,

63]. O 1s scans (

Figure 9b) revealed peaks at 532.52 eV (Si–O–Si band) and 531.18 eV (C=O in PVP), while 529.84 eV (C–O), 533.38 eV (O–C=O), and 529.84 eV (O–C=O) were attributed to carbon-containing groups of silane precursors [

62]. Peaks at 283.53 eV, 285.08 eV, 286.61 eV, and 288.34 eV in the C 1s (

Figure 9c) scans indicated PVP molecular structure contributions [

68]. The N 1s scan (

Figure 9d) at 400.07 eV identified N atoms from C–N in the APTES structure. These XPS results substantiate the successful incorporation of PVP K30 into APTES/TEOS–SiO

2@Si.

3.4. Characterization of Representative Core Shell and Yolk Shell Composites

Representative composites including core shell and yolk shell formations were synthesized following the proposed route, with one sample featuring PVP-protected SiO

2 shells and PEI-crosslinked structure. Surface composition changes in these structures (core shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si and yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si) were investigated using XPS analysis. High-resolution scans are depicted in

Figure 10, and survey spectra of the composites are provided in

Figure S8 (Supplementary Materials).

The high-resolution Si 2p scan of the core shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si composite (

Figure 10a) exhibited two distinct peaks at 103.72 eV and 99.78 eV. The peak at 103.72 eV was attributed to the Si–O–Si band, displaying a higher intensity compared to the peak at 99.78 eV assigned to Si [

61]. These peaks align well with the reported literature. Deconvolution of the O 1s scans (

Figure 10b) revealed five components at 533.18 eV (Si–O–Si), 534.64 eV (O–C=O), 532.37 eV (C=O), 531.0 eV (C–O), and 535.89 eV (O–C=O) in decreasing order of intensity [

62,

65]. Additionally, the C 1s scan displayed peaks at 284.87 eV (sp

2 C=C), 286.42 eV (C–COO), 289.37 eV (C–N), 284.35 eV (sp

3 C–C), 289.37 eV (O–C=O), and 290.81 eV (C–O) [

64,

69].

The yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si sample displayed analogous peaks with reduced intensities compared to the core shell counterpart, primarily due to NaOH etching. As shown inn

Figure 10e, the Si 2p scan revealed a reduced intensity in the Si–O–Si band at 103.54 eV, and the O 1s scans (

Figure 10f) displayed diminished intensities for Si–O–Si (533.37 eV), O–C=O (534.86 eV), C=O (532.22 eV), O–C=O (535.85 eV), and C–O (530.82 eV). However, the sp

3 C–C and C–O peaks in the C 1s scan of the core shell composite (

Figure 10c) disappeared in the yolk shell composite (

Figure 10g) after SiO

2 removal, indicating the destruction of carbon structures. This was consistent with

Figure 8 TEM images for composites lacking PVP K30 surface protection. Detected chemical species in O 1s scans aligned well with C 1s results, attributed to SiO

2, carbon-containing ligands, PDA carbon coating, and PEI crosslinks.

In the N 1s scan of the core shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si sample (

Figure 10d), two peaks were observed at 400.54 eV and 398.21 eV. Similarly, in the yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si sample, these peaks appeared at 400.45 eV and 398.16 eV. These peaks were attributed to protonated amines resulting from APTES hydrolysis and C–N bonds, respectively [

65]. The C–N bond, detected in O 1s, C 1s, and N 1s scans, signified the crosslinking reaction between amino groups and catechol in oxidized PDA polymer chains with PEI molecules. The expected formation of PDA–PEI networks was supported by Schiff base or Michael addition reactions, illustrated in

Figure S9 (Supplementary Materials) [

70].

XPS results (

Figure 11) underscore the impact of PVP K30 and the contributions of PEI crosslinks in reinforcing carbon coating durability in the core shell PDA@SiO

2@Si versus yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si composite. The corresponding survey spectra are provided in

Figure S10 (Supplementary Materials).

Similar peak characteristics were identified in both composite samples. For instance, the Si 2p spectra of the core shell PDA@SiO

2@Si in

Figure 11 exhibited a Si–O–Si band, mirroring the presence of this band in the yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si sample (

Figure 11e), albeit with a slightly diminished intensity. Correspondingly, O 1s scans (

Figure 11b,f) for both samples revealed comparable chemical compositions with analogous binding energies, including Si–O–Si, C=O, C–O–C, C–O, and O–C=O, in order of decreasing peak intensities. C 1s scans (

Figure 11c,g) for both samples demonstrated consistent peaks for sp

2 C=C, C–COO, C–N, O–C=O, and C–O. Additionally, N 1s scans (

Figure 11d,h) showed no substantial variations between the two composites. Despite the reduced peak intensities of O-containing groups in PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si due to etching, noteworthy sustenance of the sp

3 C–C peak at 284.47 eV and C–O peak at 289.92 eV in the C 1s spectrum (

Figure 11g) emphasized the pivotal role of PVP surface protection and PEI crosslinking in constructing a resilient carbon coating capable of withstanding NaOH etching during template removal.

Raman spectroscopy was performed to determine defect quantity within the carbon coating layer and identify the degree of graphitization of representative core and yolk shell composites. TEOS–SiO

2@Si, APTES/TEOS–SiO

2@Si and PVP–SiO

2@Si samples were also analyzed for reference purposes. Recorded spectra of each representative composite and reference samples are summarized in

Figure 12.

The recorded Raman spectra depicted characteristic peaks at 511 cm

−1 and 918 cm

−1, indicative of Si, across all samples, affirming the preservation of Si crystallinity and intrinsic features. Notably, the Si peak intensity exhibited a decline following APTES addition, suggesting the formation of an amorphous SiO

x layer around Si. A further reduction in Si peak intensity occurred upon PVP loading onto SiO

2 shells. All representative composite samples exhibited discernible D bands (~1350 cm

−1) and G bands (~1590 cm

−1), typical of sp

2-bonded carbons in graphite and related structures after the pyrolysis of PDA and PEI molecules [

71]. Second-order vibrations around ~2400 cm

−1 observed in PDA–PEI-containing composites indicated the partial graphitization of the carbon coating [

72]. Stronger G bands compared to D bands across composites suggested the integration of PDA and PEI into a crystalline graphitic matrix, in alignment with TEM findings. The I

D/I

G ratio, quantified after curve fitting using a Gaussian–Lorentzian model, reinforced these observations, as detailed in

Figures S11–S14 and Table S1 (Supplementary Materials) [

73].

The increase in the I

D/I

G value from core shell PDA@SiO

2@Si (0.84) to core shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si (0.85) is attributed to increased sp

2-carbon edge atoms resulting from the co-polymerization of PDA and PEI, followed by graphitization during thermal treatment. A parallel increase in the I

D/I

G value for yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si (0.85) suggests successful carbonization of polymer coatings. In contrast, PVP–SiO

2@Si exhibited minimal variations in the I

D/I

G ratio, potentially due to the dominant Si signals masking the carbon contribution from PVP K30. Yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si (0.86) displayed the highest I

D/I

G value, indicating PDA–PEI graphitization and the subsequent carbonization of PVP K30, offering protective properties to SiO

2 shells after thermal treatment [

74].

Figure 13 displays TG/DTA thermograms, including DTG curves, of representative composites that were subjected to controlled combustion up to 800 °C under N

2 gas protection.

TG profiles depicted in

Figure 13a delineate four distinct phases based on the composition of representative samples. Phase I, characterized by a slight decrease in sample weight at approximately 50–90 °C, was attributed to the loss of physisorbed water on the composite surface. The subsequent phase involved the decomposition of polymers, extending broadly up to around 220 °C. In Phase II, a gradual weight loss occurred within the temperature range of ~400–550 °C. Notably, the core shell PDA@SiO

2@Si sample exhibited a sharp decline in weight, indicative of rapid PDA coating degradation without the assistance of PEI crosslinks or PVP K30 molecules. This observation was corroborated by the DTG profile in

Figure 13b. The calculated total carbon content for the core shell PDA@SiO

2@Si sample was approximately 60 wt.%, consistent with the fabrication ratio. Phase III commenced at ~550 °C, marked by sample weight loss due to the oxidation of exposed Si particles that were vulnerable to elevated temperatures [

32]. The oxidation reaction persisted into Phase IV, concluding at ~700 °C when all sample components combusted, leaving Si and SiO

x components. Remarkably, composites with either PEI crosslinking or PVP K30 surface protection exhibited superior thermal stability, with minimal sample weight loss at temperatures exceeding 550 °C, emphasizing the effectiveness of the PDA carbon coating reinforced by PEI crosslink structures.

The enhanced thermal stability of PDA–PEI co-polymerized coating structures was validated through the DT-TGA and DTG curves of the representative yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si composite samples, as depicted in

Figure 13c. The TG curve exhibited a consistent and sharp weight loss of approximately 10%, corresponding to the removal of both physisorbed and chemisorbed water. Additionally, the TG curve displayed a small exothermic peak around 100 °C, attributed to moisture loss, a broad endothermic peak centered at 200–400 °C signifying polymer decomposition, and a broad exothermic signal emerging from 500 °C due to SiO

2 oxidation. The DTG curve further illustrated water removal from a small endothermic peak at ~100 °C and actual polymer degradation from a broad endothermic peak within the range of ~200–400 °C. The decomposition of carbon components was confirmed by a broad exothermic signal spanning ~400–550 °C, while endothermic peaks at ~700 °C indicated the transition into SiO

x [

75].

Apart from a minor weight loss observed at ~50–100 °C due to the evaporation of adsorbed water molecules, depicted in

Figure 13b, no substantial changes in sample weights were noted at 550 °C for the remaining composite samples, as illustrated in

Figure 13d. The complete combustion of carbon-based compounds typically occurs from ~400–550 °C. However, the representative yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si composite only exhibited a slight decrease in sample weight at ~700 °C, suggesting that the composite fabrication and design effectively prevented the thermal oxidation of Si. Based on sample weight loss, the total carbon content in yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si was calculated to be ~18%, while the silicon content was ~73%, stemming from the combined contributions of SiO

2 from APTES, TEOS, and pure Si nanoparticles.

3.5. Electrochemical Performances of Representative Core Shell and Yolk Shell Composites

The electrochemical performances of representative yolk and core shell composite samples were first characterized by CV. The results are presented in

Figure 14.

All composite samples demonstrated two distinct peaks at 0.30–0.32 V and 0.72–0.79 V during the first cathodic scan. They were ascribed to initial electrochemical reactions between bulk Si and Li

+ atoms which led to formation of irreversible lithiated precipitates. Si phase transformations and corresponding chemical reactions are summarized in

Table 1 [

37].

The disappearance of cathodic peaks between 0.72 V and 0.79 V in the second cycle indicates the stabilization of the SEI film after the initial cycle. Subsequent anodic scans revealed two broad oxidation peaks centered at 0.47–0.53 V and 0.30–0.32 V, signifying the delithiation processes of Li

4.2Si and the complete delithiation into amorphous Si (Li

xSi), respectively. While the core shell PDA@SiO@Si sample exhibited less polarization (

Figure 14a), hydrothermally fabricated counterparts (

Figure 14b) demonstrated electrode activation with a gradual increase in the intensities of both cathodic and anodic scans in subsequent cycles. Similarly, PVP-surface-protected composites (

Figure 14c) showed gradual electrode activation compared to their less polarized counterparts (

Figure 14d). Additionally, cyclic voltammetry (CV) scans of the core shell PDA–PEI@TEOS–SiO

2@Si composite at room temperature (

Figure S11) displayed similar peak observations and qualities, although key oxidation peaks during the delithiation process were not clearly manifested, suggesting challenges in retrieving Li

+ from Li

xSi alloyed components during the reaction.

Electrochemical performances of core shell, yolk shell structures, and PVP surface-protected PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si were evaluated at 0.1 A g

−1 for 100 cycles (

Figure 15a). The yolk shell composite demonstrated superior discharge capacity, starting at 719 mAh g

−1 with an initial Coulombic efficiency (ICE) of 47.94%. ICE increased to 94% after five cycles and consistently exceeded 98% in subsequent cycles.

The observed phenomenon of low ICE followed by a significant increase in the second cycle for Si-based anodes is linked to the formation and stabilization of the SEI layer. This behavior, known as SEI activation, involves an irreversible and necessary consumption of Li+ during the initial cycles. In the first discharge cycle, Li+ is intercalated into the Si electrode structure, resulting in the formation of lithiated precipitates. The expansion and contraction of the Si volume induce mechanical stress, causing morphological pulverization and SEI layer breakdown. Cracks in the Si morphology lead to the construction of a new SEI layer, consuming additional Li+ and contributing to reduced reversible Li+ availability during subsequent charging cycles. As the lithiation and delithiation cycles progress, the SEI undergoes stabilization, becoming more robust and protective. After SEI layer stabilization, the Si anode attains enhanced stability, facilitating the more effective storage and release of Li+, thereby improving CE values in subsequent cycles.

The galvanostatic charge and discharge profiles of the exemplary composite, as depicted in

Figure 15b, exhibited minimal electrode polarization with overlapping profile scans across increasing cycle numbers. The low ICE of Si-based anodes is typically attributed to the decomposition reaction at the SEI layer, consuming Li

+ and diminishing available reversible Li

+ during initial cycles. The representative yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si sample demonstrated a discharge capacity of 539.44 mAh g

−1 after 100 cycles, achieving a CE of 98%. Moreover, the CE stabilized after the initial SEI formation, as illustrated in

Figure 15c.

The yolk shell structures performed better than its core shell counterparts in terms of cycling performance and CE stability at low-current density conditions for 100 cycles. Comparing the yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO2@Si composite sample without PVP K30 and the representative composite PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO2@Si sample, the PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO2@Si sample was able to maintain 539.44 mAh g−1, only slightly higher than the 531.25 mAh g−1 of yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO2@Si after 100 cycles.

Meanwhile, even with the help of PVP K30 surface protection, the core shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO2@Si composite sample demonstrated inferior cycling performance with a capacity of only 339.62 mAh g−1 after 100 cycles. This result highlights that the role of void spaces in yolk shell structures is sufficient in absorbing the internal volume changes of Si and stabilizing cycling performance. This result concludes that the PVP K30 polymer significantly affects the electrochemical performance of core shell samples at low-current density testing and yolk shell samples at high-rate loading.

The variations in cycling performance and CE between PDA–PEI@SiO2@Si and PDA@SiO2@Si composites, both featuring core shell structures, result from improved electronic conductivity in the former. This enhancement is attributed to PEI crosslinking throughout the electrode, establishing continuous pathways for rapid electron and ion transport.

Rate capabilities were assessed across various current densities (0.1 to 5 A g

−1) for the composite samples, as depicted in

Figure 15d. The yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si electrode displayed superior rate performance compared to core shell composites, regardless of the presence of PVP K30 and PEI crosslinking, and exhibited no Li dendrite formation. At current densities of 0.1, 0.2, 0.3, 0.5, 1, 2, and 5 A g

−1, specific capacities were 621.21, 577.46, 537.96, 512.50, 491.53, 472.71, and 453.16 mAh g

−1, respectively. Upon returning to 0.1 A g

−1, a specific capacity of 490.73 mAh g

−1 was regained.

While the yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO2@Si composite exhibited slightly superior electrochemical performance compared to the representative yolk shell composite, a sudden capacity increase from 456.32 mAh g−1 to 476.41 at 5 A g−1 suggested a short circuit due to Li dendritic formations, common at high current densities. Similar abrupt capacity increases were observed for core shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO2@Si and core shell PDA–PEI@SiO2@Si composites. It is noteworthy that slight capacity increases in other sample composites stabilized upon reducing the current density to 0.1 A g−1, indicating satisfactory recovery after high-rate tests.

Table 2 summarizes cycling and rate performances of the representative yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si composite compared to other fabricated composites.

Electrochemical impedance measurements were conducted before and after the 100th cycle to elucidate factors contributing to the enhanced Li

+ storage capacity of the representative yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si composite. Presented in

Figure 16 are Nyquist plots, with insets (

Figure 16a,b) illustrating corresponding equivalent circuit models. The circuit model considered the resistance values denoted as R

s, R

SEI, R

CT, and Warburg impedance (W

z), representing the interactions of the electrolyte solution with bulk Si, Li

+ migration through the SEI layer, charge transfer resistance, and Warburg diffusion, respectively. Additionally, double-layer capacitances (CPE1 and CPE2) represented constant phase elements of the cell surface film.

As depicted in

Figure 16a, Nyquist plots of the investigated composites before cycling exhibited a semicircle in the middle-frequency region and a slanted sloping line in the low-frequency region. The smaller diameter of the representative yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si before cycling indicated a lower R

CT value (73.76 Ω), signifying faster charge transfer kinetics. This enhanced charge transfer could be attributed to the synergistic effect of the yolk shell structure, facilitating direct contact between the carbon coating layer and the PVP–SiO

2@Si active material. Similarly, yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si (139.60 Ω) and core shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si (140.21 Ω) demonstrated comparable R

CT values, significantly lower than core shell PDA@SiO

2@Si (211.16 Ω) and core shell PDA––PEI@SiO

2@Si (209.23 Ω). The presence of a thick layer of amorphous SiO

2 coating in core shell composites hindered direct contact between the Si active material and the conductive PDA carbon coating, resulting in increased Li

+ tortuosity. In core shell composites, Li

+ migration needed to traverse the electronically insulating SiO

2 layer before reaching the Si active material, leading to a substantial increase in R

CT.

Following 100 cycles, the formation of a stable SEI layer was confirmed in the Nyquist plots depicted in

Figure 16b. The Nyquist plots for the fabricated electrodes exhibited two semicircles—one in the high-frequency region attributed to R

SEI and the other in the middle-frequency region representing R

CT—and a slanted line in the low-frequency region.

The representative composite displayed the smallest diameter in the high-frequency semicircle, indicating the lowest RSEI value (6.30 Ω). This reduction was attributed to the formation of a mechanically stable SEI layer facilitated by the PDA coating, preventing excessive electrolyte decomposition. Yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO2@Si also exhibited a relatively lower RSEI value (8.13 Ω) compared to its core shell counterparts, underscoring the significance of the yolk shell structure. However, a larger RCT value for yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO2@Si (19.28 Ω) compared to the representative composite (9.71 Ω) emphasized the importance of constructing yolk shell structures with PVP K30 surface protection. Core shell composites PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO2@Si (9.51 Ω) with PVP K30 demonstrated lower RSEI values than the PDA–PEI@SiO2@Si (10.77 Ω) sample, highlighting the efficacy of PVP K30 in enhancing the electrochemical performance.

The formation of a stabilized SEI film in core shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO2@Si can be elucidated by the influence of PVP K30 polymer chains when loaded into amorphous SiO2 shells. In the event of crack formation in the PDA carbon coating due to the expansion of lithiated Si and SiO2 components, the embedded PVP K30 polymer chains within SiO2 shells act as a secondary barrier, preventing direct contact with Si active materials. Furthermore, the flexibility of PVP K30 polymer chains contributes to the stable formation of SEI by serving as a buffer against the rigid and dense SiO2 layer, susceptible to crack formation during repetitive volume fluctuations. The incorporation of PVP K30 polymer chains within SiO2 also enhances the conductivity of amorphous SiO2 seeds, resulting in a slight improvement in the RCT of core shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO2@Si (23.32 Ω) compared to core shell PDA–PEI@SiO2@Si (28.01 Ω). Conversely, the absence of the PEI component in core shell PDA@SiO2@Si led to a higher RSEI (10.84 Ω) coupled with thick SiO2 shells, obstructing Li+ migration and increasing tortuosity (32.50 Ω).

Table 3 summarizes parameters acquired from Nyquist plots of fabricated composites before and after 100 lithiation/delithiation processes.

Long cycling performance stability at a high-rate loading of the fabricated composite electrode was evaluated at 1 A g

−1 for 200 lithiation/delithiation cycles. Cycling performances under prolonged cycling at a high-rate loading are illustrated in

Figure 17.

As depicted in

Figure 17a, the cycling behavior of hybrid anodes subjected to a high current density of 1 A g

−1 for 200 cycles mirrored trends observed in previous low-density cycles. In summary, initial discharge capacities for the yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si, yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si, core shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si, core shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si, and core shell PDA@SiO

2@Si composite electrodes were 853.94, 767.07, 540.98, 344.56, and 324.26 mAh g

−1 (descending in magnitude), respectively. All composite electrodes exhibited an initial decline in discharge capacity attributed to irreversible SEI formation. Discharge capacity then stabilized in subsequent cycles. Following 200 lithiation/delithiation cycles, reversible capacities of 523.50, 512.76, 319.18, 229.02, and 227.55 mAh g

−1 (in descending order) were achieved for corresponding composite electrodes.

As representative yolk shell composite electrodes, specifically yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO2@Si and yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO2@Si displayed the highest initial discharge capacities of 853.94 and 767.07 mAh g−1, respectively. After 200 cycles, both electrodes exhibited stable cycling performance, retaining reversible capacities of 523.50 and 512.76 mAh g−1, respectively, showing minimal capacity losses. Although yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO2@Si initially demonstrated a slightly higher discharge capacity, its cycling stability gradually declined after approximately 170 lithiation/delithiation cycles. In contrast, yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO2@Si demonstrated a superior cycling performance, maintaining a relatively stable capacity retention rate during extended high-density cycling. This divergence in long-cycling performance was attributed to the significant influence of PVP K30 acting as a protective barrier between the PDA–PEI coating layer and SiO2 shells during etching. Additionally, embedded PVP K30 polymer chains within SiO2 shells contributed to a flexible silica structure, mitigating particle pulverization.

Figure 17b shows CE values of cycled samples at a high-rate loading. Notably, PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si, a representative yolk shell composite, exhibited the highest initial cycling efficiency (ICE) of 50.98% among investigated composites. Si–based composite anodes typically display low ICE values due to irreversible SEI formation, leading to Li

+ consumption and reduced reversible capacity. However, CE values exhibited an increasing trend after initial cycles, gradually stabilizing over subsequent cycles. After 200 cycles, the representative composite anode demonstrated the highest CE value of 99.12% among cycled samples.

The capacity contribution for each component (i.e., Si, SiO2, APTES, TEOS, PVP K30, PDA, and PEI) can be summarized as follows. Si, due to its excellent theoretical specific capacity, was used to boost the energy density of typical graphite-based commercial anodes. SiO2 was fabricated from APTES and TEOS dual template strategy to design a yolk shell structure to provide void spaces to buffer inevitable Si volume fluctuations. The APTES was used as a structure to regulate TEOS to facilitate monodispersed SiO2 synthesis without a base catalyst and as a precursor to amino-functionalized SiO2. The PVP K30 polymers provided surface protection to prevent crack formation on the carbon coating and acted as a barrier that controls the rate of SiO2 dissolution during the etching process. The PVP K30 polymers embedded within the SiO2 shells also allowed for flexibility and conductivity to the rather amorphous and rigid SiO2 shells. The PDA coating layer was designed to encapsulate the SiO2-coated Si active material and prevent direct electrolyte contact while mitigating the low conductivity of Si. Lastly, the crosslinking reaction between PDA and PEI contributed to the construction of a 3D, bubble wrap-like, interconnected porous matrix with a thermal stability reaching up to 700 °C. Each component in the representative yolk shell composite exhibited synergistic effects that resulted in a stable cycling performance with minimal capacity loss even after 200 cycles.

Table 4 provides a summary of cycling performances, including corresponding CE values, for the representative yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si composite in comparison with other fabricated composites over an extended cycle period at a high-rate loading.

The specific surface area and pore size distribution of the cycled composites were examined through BET analysis, as illustrated in

Figure 18. The porous structure of the composites was elucidated using the BJH model. The N

2 adsorption–desorption isotherms of all obtained composites, as depicted in

Figure 18a, exhibit the characteristic type IV adsorption isotherm with distinct hysteresis loops, signifying mesoporous structural features. The BET specific surface area (S

BET) of the representative composites ranges from 220–650 m

2 g

−1, with corresponding total pore volumes falling within the range of 0.12–0.67 cm

3 g

−1, as summarized in

Table S2 (see Supplementary Materials). The pore size distributions, calculated from the adsorption branch of the isotherms, reveal that the resulting composites possess a micro/mesoporous structure, with mesopores centered at approximately 2–4 nm, as depicted in

Figure 18b.

The variation in specific surface areas among the investigated composites offers additional insights into the observed differences in electrochemical performance during prolonged cycling at high-rate loading. A higher specific surface area provides more active sites for the interaction between the electrode material and the electrolyte. The recorded SBET values for the studied composites in ascending order were 224.56, 226.40, 409.05, 589.83, and 654.63 m2 g−1 for the core shell PDA@SiO2@Si, core shell PDA–PEI@SiO2@Si, core shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO2@Si, yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO2@Si, and yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO2@Si, respectively.

The BET analysis results indicate that the representative yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO2@Si composite, characterized by the lowest pore volume (0.12 cm3 g−1), highest SBET value, and greatest specific surface area attributed to mesopores (570.96 m2 g−1), exhibited the most stable electrochemical performance in terms of cycling and rate stability. The notable increase in the contact area enhanced the electrode–electrolyte interface, facilitating efficient ion transfer during both charging and discharging cycles. The high specific surface area contributed to improved ion diffusion, allowing Li+ ions to traverse the electrode structure with reduced diffusion path lengths. Moreover, the extensive surface area of mesopores within the electrode structure helped distribute Si volume fluctuations effectively, thereby minimizing mechanical stress and mitigating issues related to electrode degradation over multiple cycles.

Achieving the right balance between optimal pore size and distribution was identified as crucial for the electrochemical performance of the other studied composites. Notably, the yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si sample exhibited relatively higher specific surface areas of micropores with a small pore volume (0.13 cm

3 g

−1), leading to limited Li

+ diffusivity and compromised reversible capacity during high-rate loading over extended cycling (see

Figure 17a, depicting capacity loss after 170 cycles). Conversely, core shell composites with high pore volumes and relatively higher specific surface areas of micropores than mesopores resulted in lower S

BET values and, consequently, lower reversible capacities under both cycling conditions.

To substantiate the electrochemical cycling stability of the investigated composites, we examined the surface topography of the fabricated anode materials before and after the 200th cycle at 1 A g

−1 (

Figure 19).

Prior to the initial cycle, electrode surfaces exhibited a sponge-like porosity, featuring aggregated SiO

2@Si nanoparticles dispersed within interconnected carbon structures. Notably,

Figure 19a illustrates a representative yolk shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si sample with a uniform surface without cracks, unlike the yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si sample shown in

Figure 19c, which displayed slight cracks despite sharing the same yolk shell structure. This distinction in surface morphology was attributed to enhanced flexibility conferred by the embedded PVP K30 polymer within the SiO

2@Si shells in the representative composite. Similarly,

Figure 19e demonstrates a comparable porous surface topography without cracks in the core shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si owing to the presence of the PVP K30 polymer during SiO

2 synthesis.

Conversely, the absence of PVP K30 polymer to provide flexibility to SiO

2 shells and PEI polymer for crosslinking between SiO

2@Si nanoparticles was evident in

Figure 19g (core shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si) and

Figure 19i (core shell PDA@SiO

2@Si). Both electrodes exhibited severe crack formation even before the lithiation/delithiation process. These cracks occurring between SiO

2@Si aggregates impeded effective contact among active materials, resulting in compromised electrochemical performance, particularly in terms of discharge capacities.

Following 200 cycles at 1 A g

−1, a smooth and crack-free surface of the representative composite electrode was found as shown in

Figure 19b. Recurring electrochemical reactions resulted in a thin layer covering active materials on the electrode surface. Both yolk shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si and core shell PDA–PEI@PVP–SiO

2@Si samples displayed a similar surface topology, with pores initially present before cycling being filled with accumulated reaction by-products on the electrode surface (see

Figure 19d and

Figure 19f, respectively). In contrast, core shell PDA–PEI@SiO

2@Si and core shell PDA@SiO

2@Si samples exhibited severe surface cracks even before cycling due to the inflexible and unstable nature of their electrode structures. These cracks, filled with aggregated by-products (depicted by scattered gray areas in

Figure 19h,j), exposed active Si nanoparticles to direct electrolyte parasitic decomposition, serving as nucleation sites for a thick and non-uniform SEI film after lithiation.

The electrochemical cycling stability of investigated composite anodes, even under high-rate loading, was confirmed by SEM images, which revealed negligible damage to the electrode structure.

Figure S17 provides insights into the morphology of composites before and after cycling. The spherical configuration of active Si nanoparticles enveloped by carbon coating layers remained intact with minimal particle expansion. Notably, exposed SiO

2@Si nanoparticles were not detected. The internal volumetric fluctuations of Si active material within the polymer carbon matrix were suppressed. Consequently, electrode structures exhibited sustained electrochemical cycling stability over 200 cycles.