Occupational Health and Safety Management System of a South African University Setting

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

2.2. Research Design

2.3. Sampling Frame

2.4. Sample Size

- n = Sample size;

- N = Total Population Size;

- e = Represents the desired margin of error.

2.5. Sampling

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Data Analysis

2.8. Validity and Reliability

3. Results

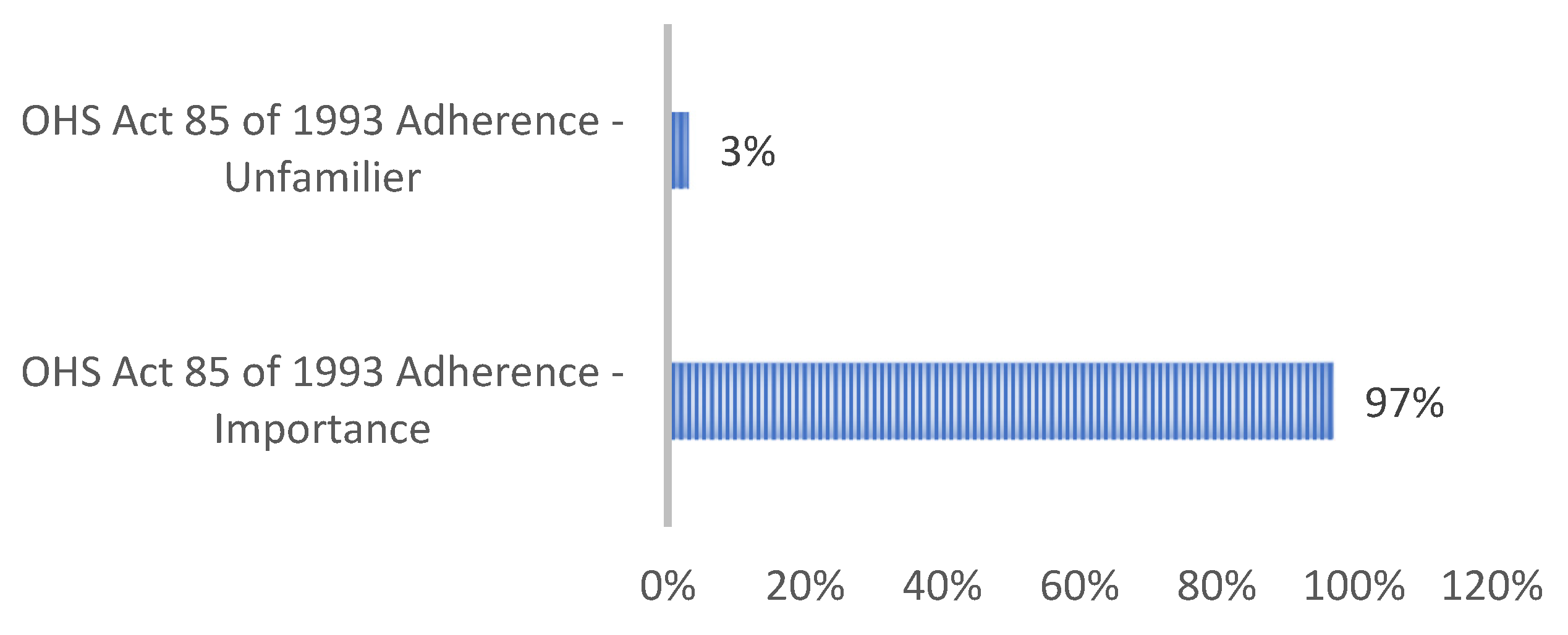

3.1. The University’s Commitment Towards Policy Compliance

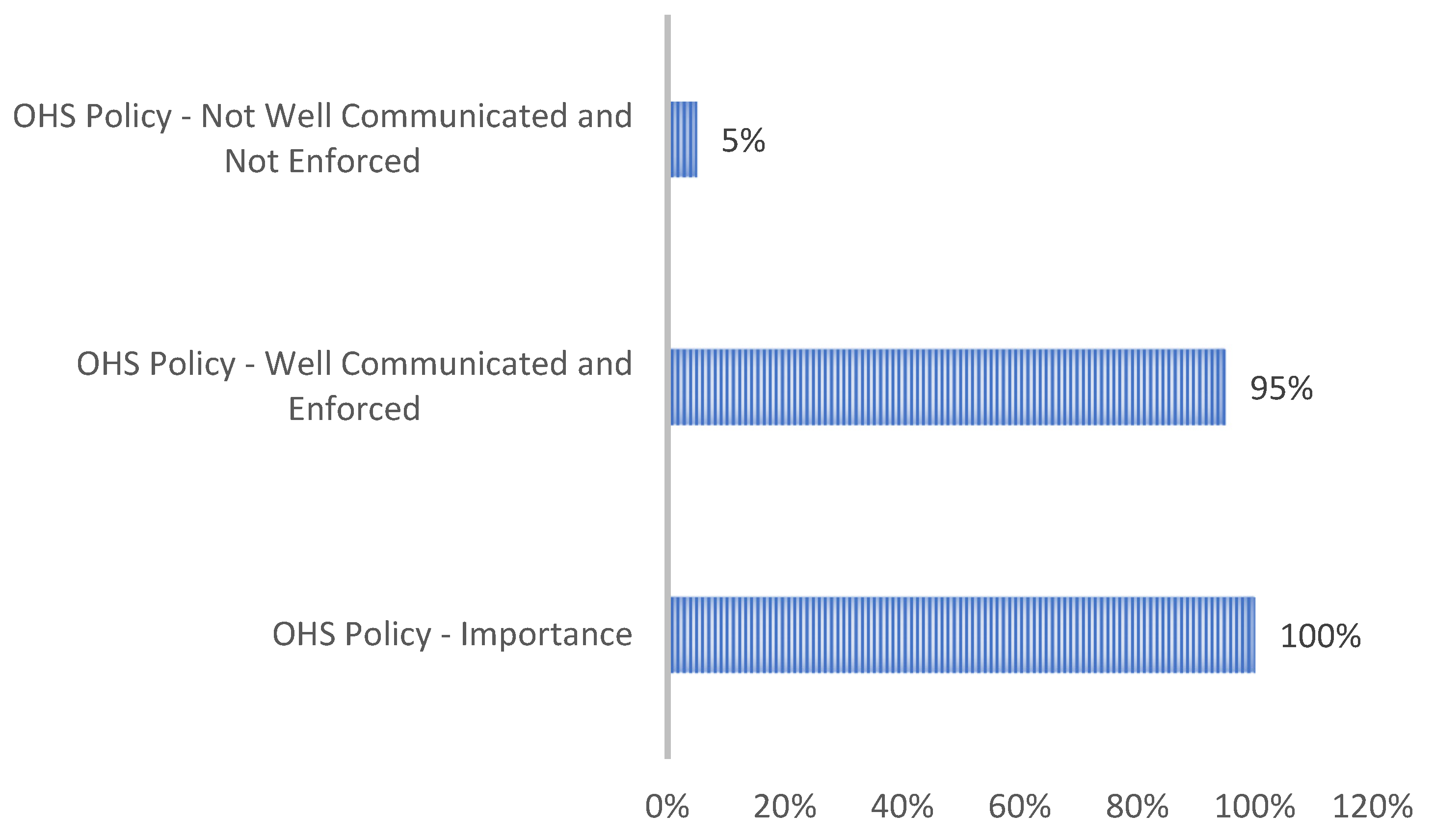

3.2. Significance of Establishing an Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) Policy in the University Setting

3.3. Organizing Roles and Responsibilities for an Effective Implementation of the Occupational Health and Safety Management System

3.4. Challenges and Barriers in Adhering to the Provisions of Sections 8 and 14 of the Occupational Health and Safety Act 85 of 1993

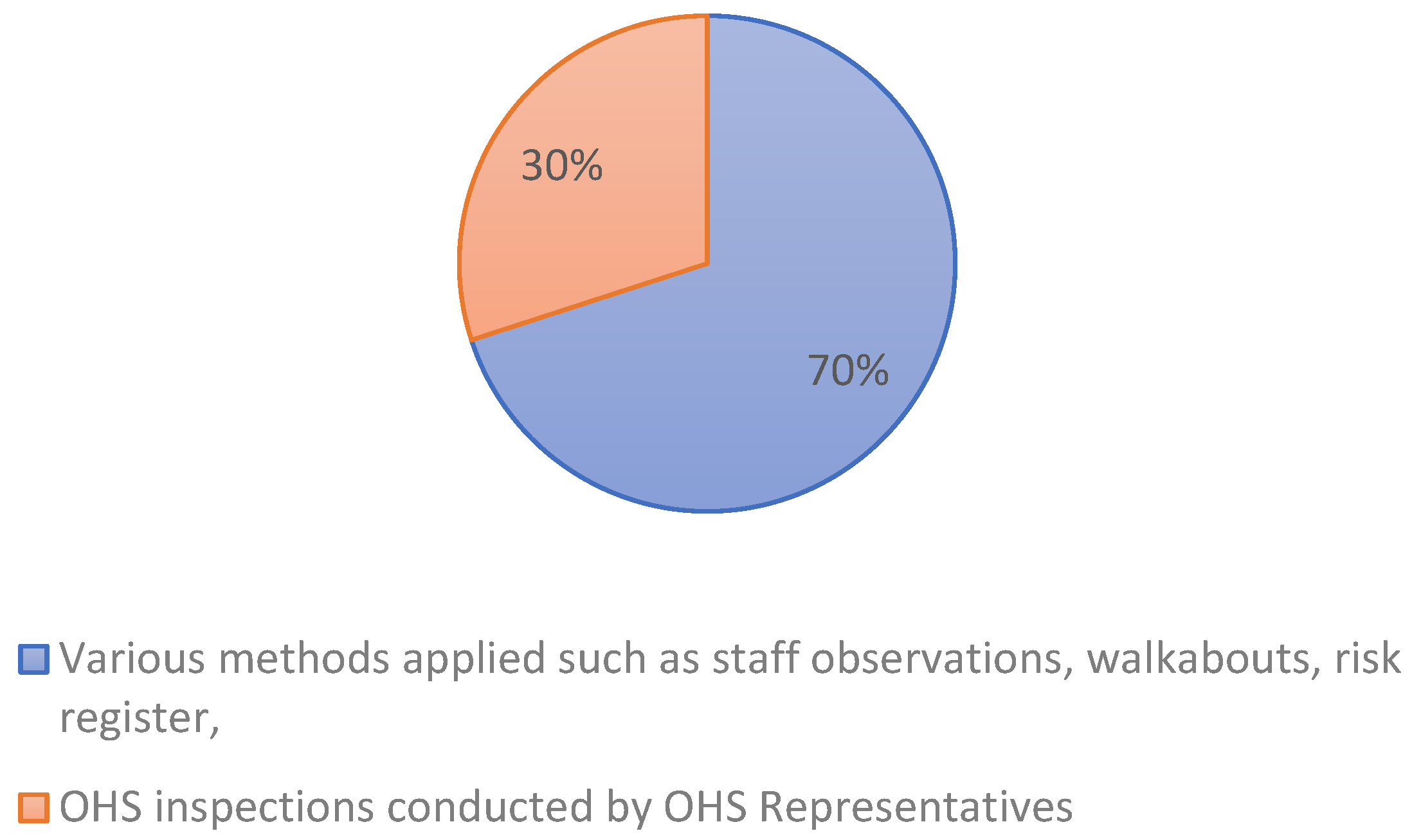

3.5. The Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (HIRA) Process in the University

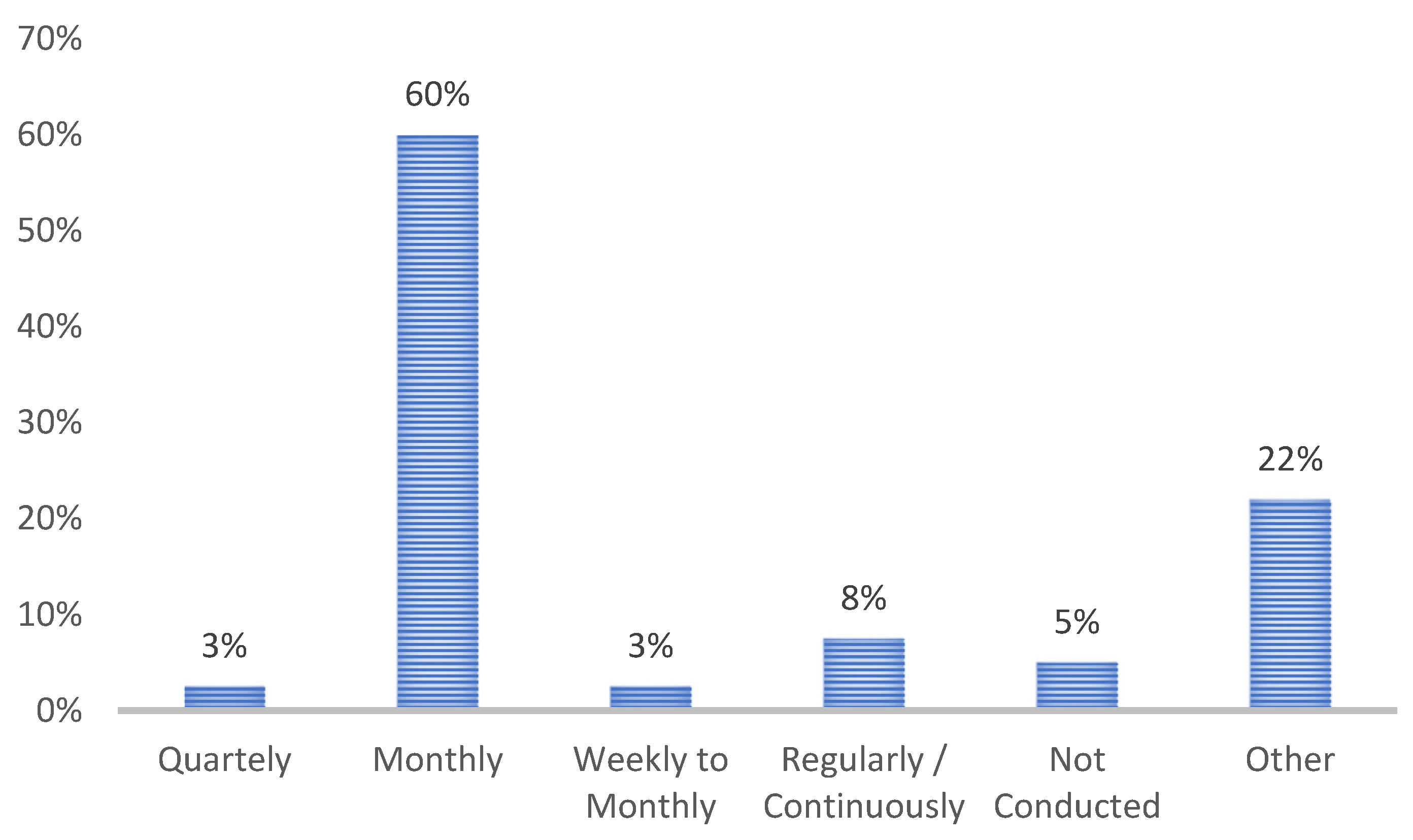

3.6. Review the Frequency of Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment

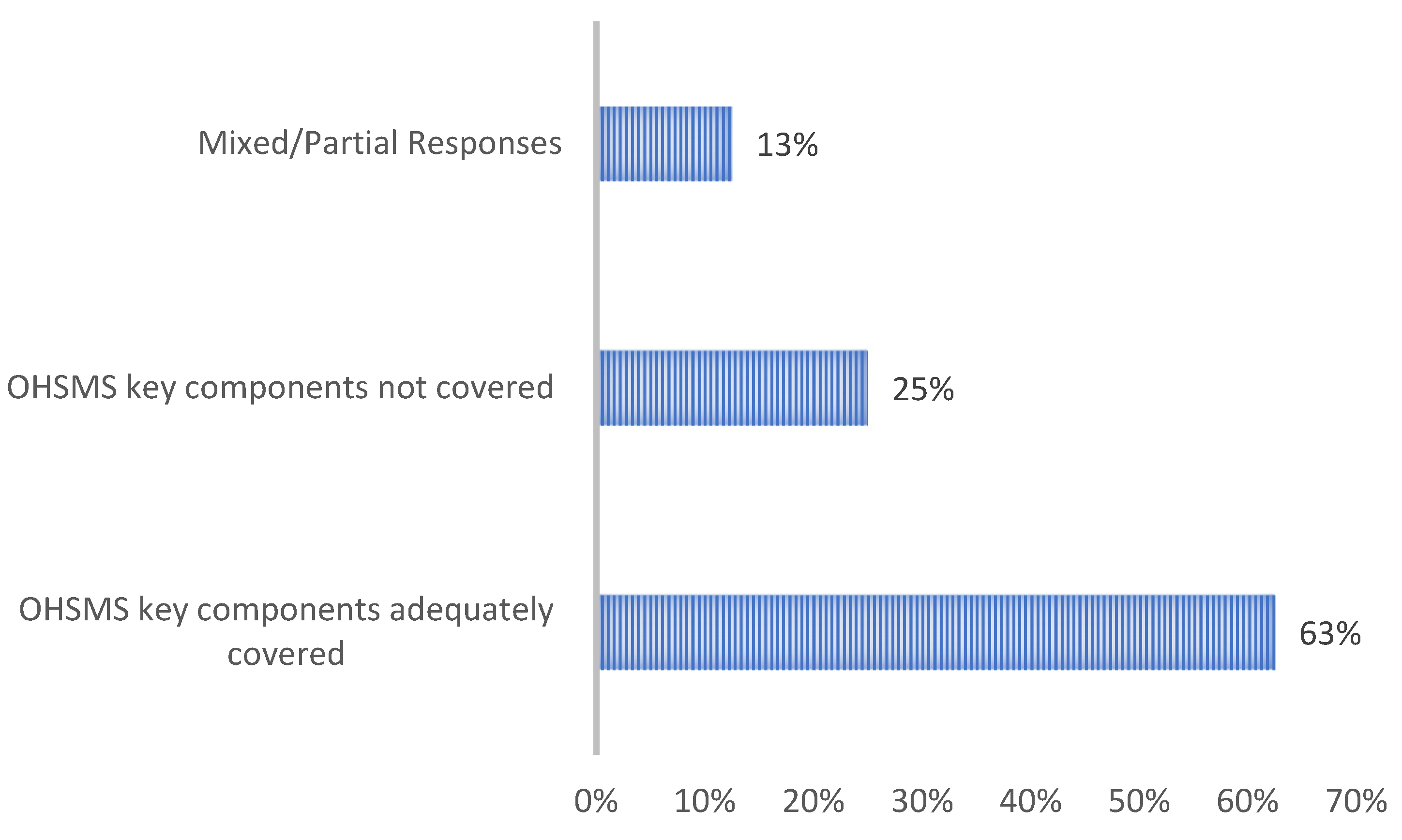

3.7. Implementation of Key Components of the Occupational Health and Safety Management System at the University

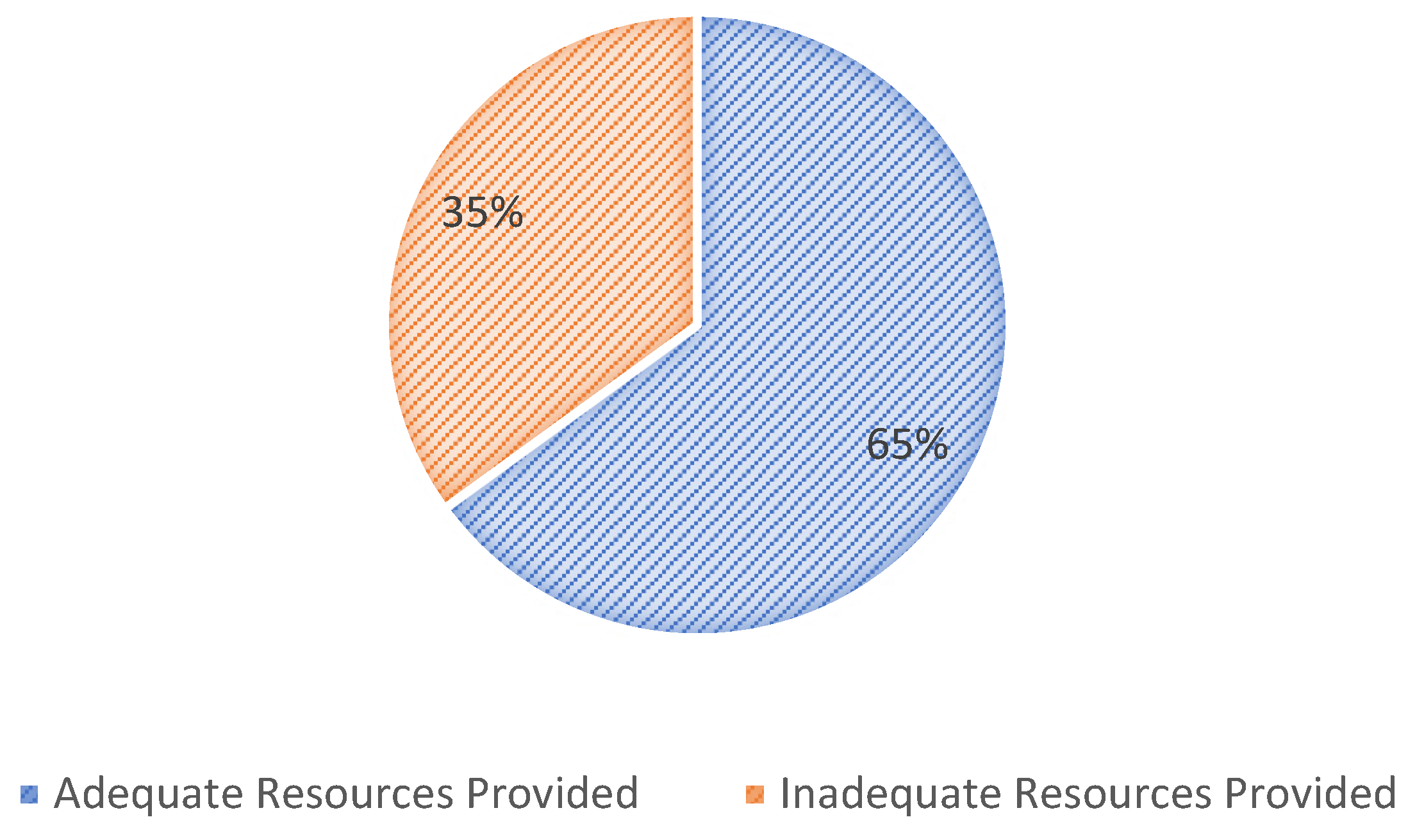

3.8. Resource Availability for the Effective Implementation of the Occupational Health and Safety Management System

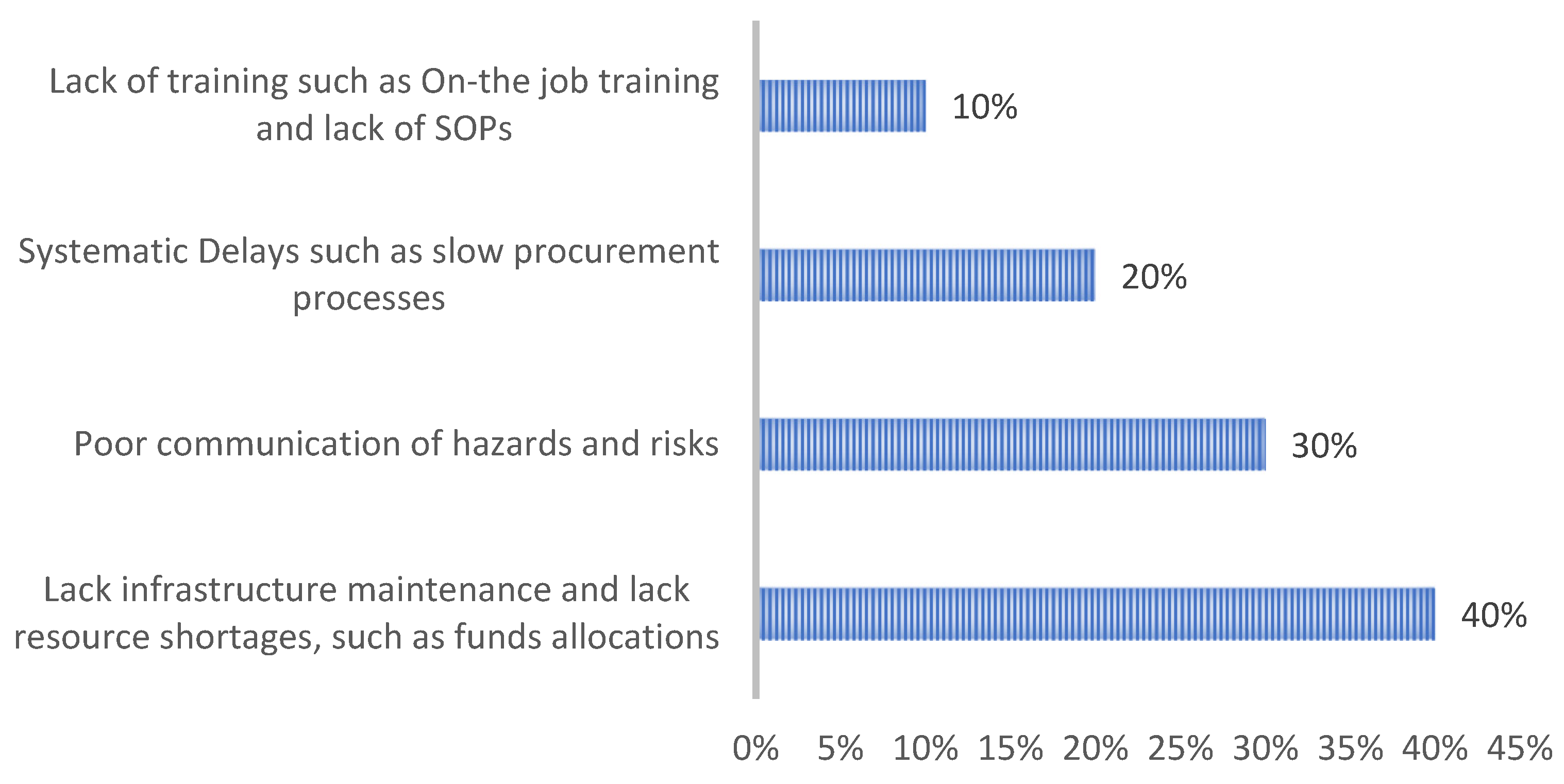

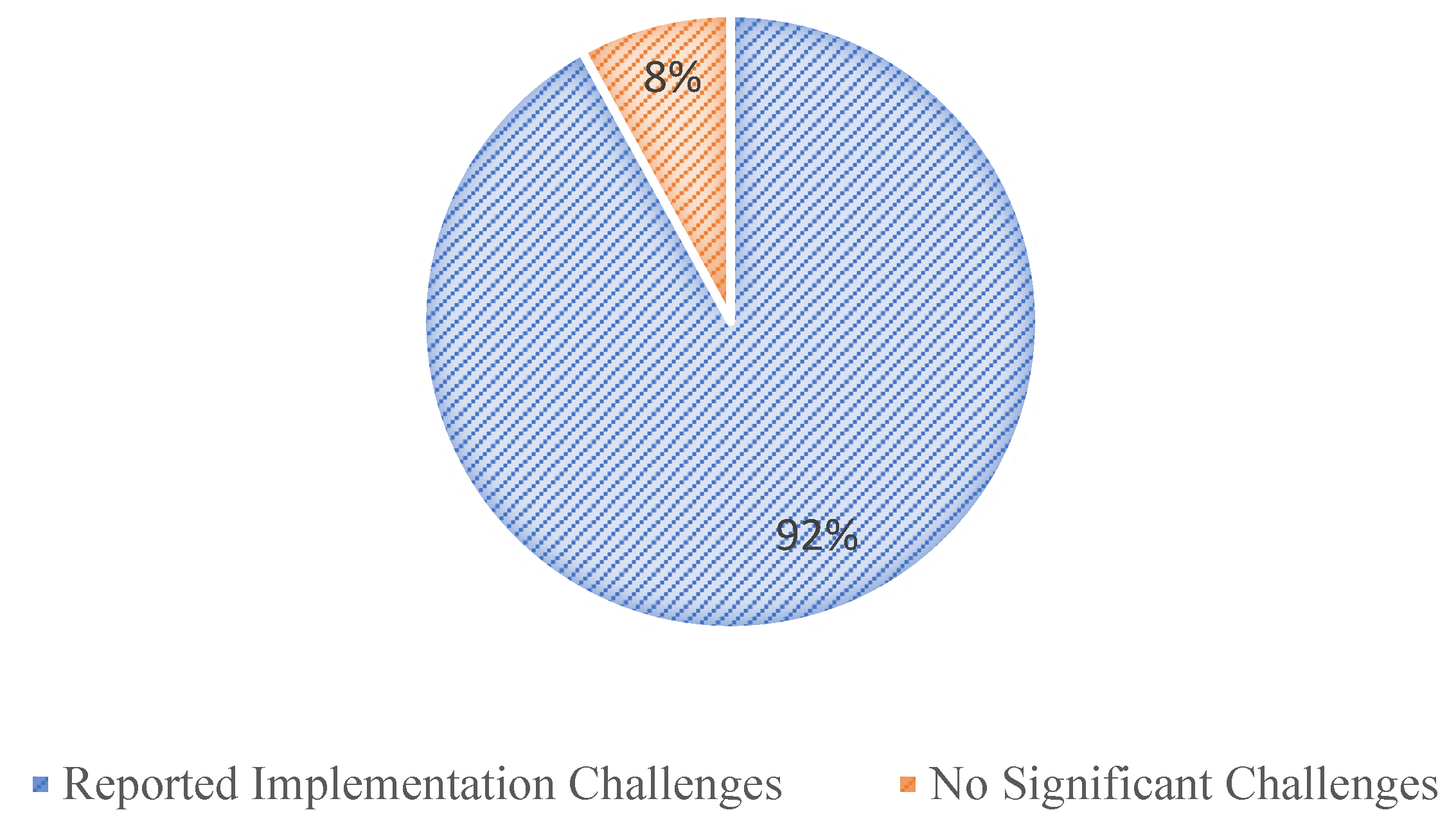

3.9. Challenges in the Implementation of the Occupational Health and Safety Management System

3.10. Indicators for Evaluating and Monitoring OHSMS Performance

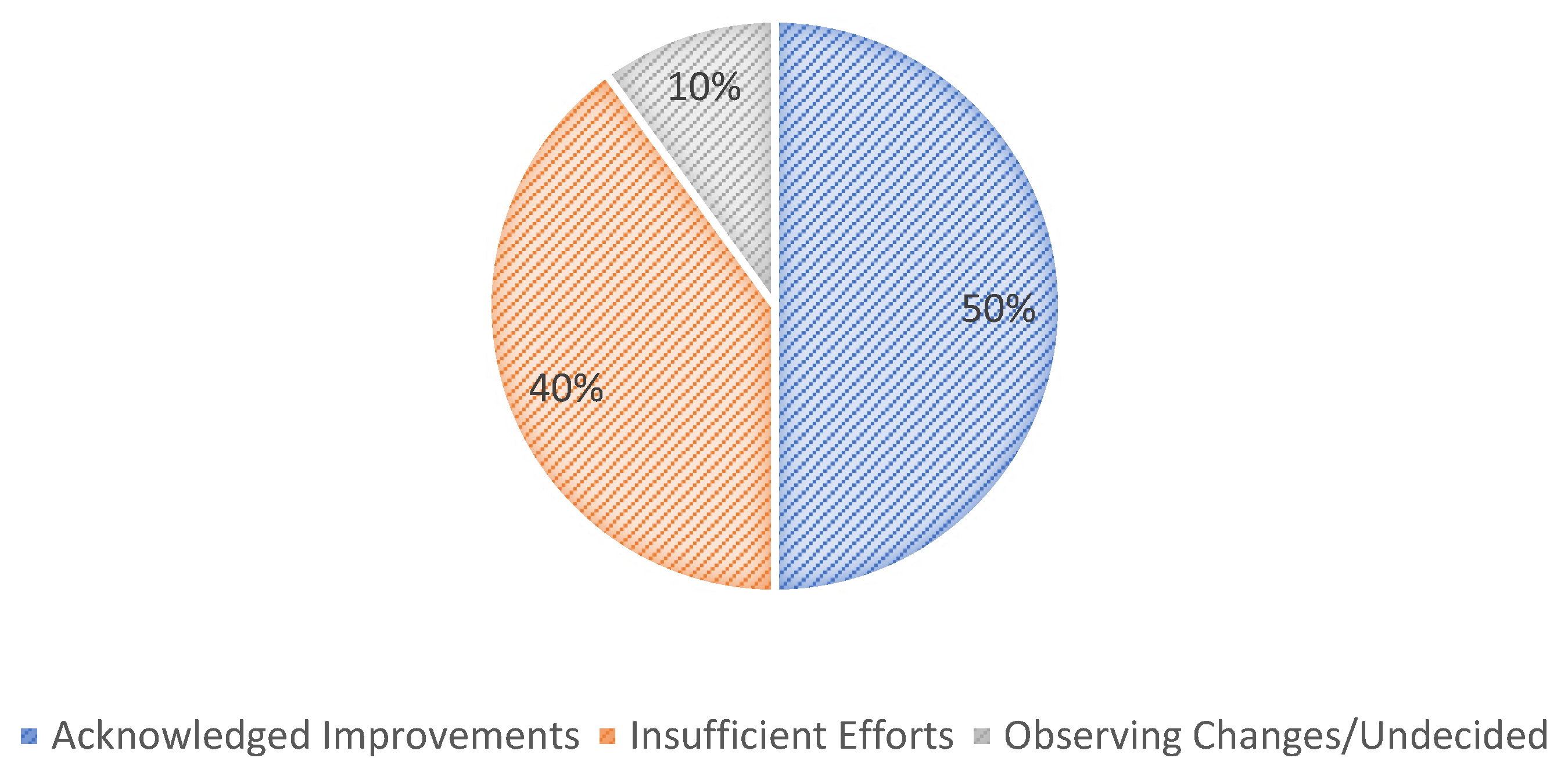

3.11. Management Review of the Occupational Health and Safety Management System Performance

3.12. Observations of Roles, Attitudes, and Behaviors During Evacuation Drills in a University Setting

3.12.1. Attitude of Participants Observed During the Emergency Evacuation Drill

3.12.2. The Behavior of Participants Observed During the Emergency Evacuation Drills

3.13. Document Review of Occupational Health and Safety Records

3.13.1. Review of Occupational Health and Safety Policy of the University

3.13.2. Review of Occupational Health and Safety Procedures

3.13.3. Review of Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment Registers

3.13.4. Evaluation of Incident Reports

3.13.5. Occupational Health and Safety Training Records

OHS Representatives Training

First Aid Training (Level 1)

Training of Fire Marshals

Legal Liability Training for Heads of Departments

3.13.6. Review Records on the Establishment of Occupational Health and Safety Committees

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rodriguez l Kramer, S.; Sherriff, B. Investigating Risk and Protective Factors to Mainstream Safety and Peace at the University of South Africa. 2013. Available online: https://www.ajol.info/index.php/asp/article/view/136079/125570 (accessed on 29 July 2023).

- Shabani, T.; Jerie, S.; Shabani, T. Overview of quality health safety and environmental management systems implementation in Zimbabwe. Saf. Extrem. Environ. 2024, 6, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muhammad, K.B.; Thamrin, Y. The Effect of Implementing Occupational Safety and Health Programs on Employee Productivity at PT. Consolidated Electric (CEPA) Power Asia Wajo District. Idea Health J. 2021, 1, 97–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ledic Neto, J.; Moro, A.R.; Ensslin, S.R. Occupational health and safety management systems: A systemic approach. Rev. Bras. Cineantropometria Desempenho Hum. 2024, 26, e91514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammedi, H.; Teymouri, H. The Assessment of Health, Safety and Environment Management System in Zanjan Zinc Industrial Plants from the Resilience Engineering Perspective in 2018. Ioh 2020, 17, 836–854. [Google Scholar]

- Johanes, M.; Mark, M.; Steven, J. A global review of implementation of occupational safety and health management systems for the period 1970–2020. Int. J. Occup. Saf. Ergon. 2023, 29, 821–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nugroho, A.; Herzanita, A.; Latief, Y.; Sagita, L. Evaluation of an Occupational Health and Safety Management System in Universitas Indonesia. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Health and Medical Sciences (AHMS 2020), Virtual Conference, 18 July 2020; Atlantis Press: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2021; pp. 251–255. [Google Scholar]

- Subhani, M. Study of Occupational Health & Safety Management System (OHSMS) in Universities’ Context and Possibilities for Its Implementation: A Case Study of University of Gavle. Available online: https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A327619&dswid=-879 (accessed on 12 March 2025).

- Hossain, M.A.; Hossain, M.M.; Tarannum, S.; Chowdhury, T.H. Factors affecting OHS practices in private universities: An empirical study from Bangladesh. Saf. Sci. 2015, 72, 371–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashyap, U.; Nandan, A. Implementation of occupational health and safety assessment series 18001: 2007 in an Indian University. Res. J. Eng. Technol. 2015, 6, 343–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Syed-Mohamad, S.M.; Siraj, M.E.; Samsudin, N.H.; Jaafar, M.H.; Iskandar, Y.H. Occupational safety and hazards in university: The development and application of text categorization technology. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2022, 197, 627–634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lestari, F.; Bowolaksono, A.; Yuniautami, S.; Wulandari, T.R.; Andani, S. Evaluation of the implementation of occupational health, safety, and environment management systems in higher education laboratories. J. Chem. Health Saf. 2019, 26, 14–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Álvarez-Chávez, C.R.; Marín, L.S.; Perez-Gamez, K.; Portell, M.; Velazquez, L.; Munoz-Osuna, F. Assessing college students’ risk perceptions of hazards in chemistry laboratories. J. Chem. Educ. 2019, 96, 2120–2131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngcece, S. An Investigative Study on the Perceptions of University of KwaZulu-Natal Risk Management Services (RMS) on Campus Safety. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Howard College, Durban, South Africa, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Mphahlele, A. Conceptualisations of and Responses to Plagiarism in the South African Higher Education System. Unpublished Ph.D. Dissertation, Rhodes University, Makhanda, South Africa, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Good, P. Undergraduate Education in South Africa. In Changing Higher Education for a Changing World; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK, 2020; Volume 223. [Google Scholar]

- Boru, T. Chapter Five Research Design and Methodology. 2018. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/329715052_CHAPTER_FIVE_RESEARCH_DESIGN_AND_METHODOLOGY_51_Introduction_Citation_Lelissa_TB_2018_Research_Methodology_University_of_South_Africa_PHD_Thesis (accessed on 14 January 2023).

- Creswell, J.W.; Clark, V.P. Mixed Methods Research; Sage: Thousand Oaks, CA, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J.W.; Zhang, W. The application of mixed methods designs to trauma research. J. Trauma. Stress Off. Publ. Int. Soc. Trauma. Stress Stud. 2009, 22, 612–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Madonsela, B.S.; Machete, M.; Shale, K. Indigenous knowledge systems of solid waste management in Bushbuckridge rural communities, South Africa. Waste 2024, 2, 293–311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osahon, O.J.; Kingsley, O. Statistical approach to the link between internal service quality and employee job satisfaction: A case study. Am. J. Appl. Math. Stat. 2016, 4, 178–184. [Google Scholar]

- Obianefo, C.A. Economic Analysis of Adopting Good Agronomic Practices Among Rice Farmers in Value Chain Development Programme, Anambra State, Nigeria. Issues Agric. 5 February 2020. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/C-A-Obianefo/publication/336832174_ECONOMIC_ANALYSIS_OF_ADOPTING_GOOD_AGRONOMIC_PRACTICES_AMONG_RICE_FARMERS_IN_VALUE_CHAIN_DEVELOPMENT_PROGRAMME_ANAMBRA_STATE_NIGERIA/links/5db98c6e4585151435d26030/ECONOMIC-ANALYSIS-OF-ADOPTING-GOOD-AGRONOMIC-PRACTICES-AMONG-RICE-FARMERS-IN-VALUE-CHAIN-DEVELOPMENT-PROGRAMME-ANAMBRA-STATE-NIGERIA.pdf (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- Gillen, M. The NIOSH construction program: Research to practice, impact, and developing a national construction agenda. J. Saf. Res. 2010, 41, 289–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maseko, M.M. Effects of Non-Compliance with the Occupational Health and Safety Act (No. 85 of 1993) Among the Food and Beverage Industries in Selected Provinces of South Africa. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2016; p. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual. Res. Psychol. 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adenan, N.S.; Jamian, R.B.; Wahab, M.H. Employee’s Perceptions on Occupational Safety and Health Management System (OSHMS) in A Wood Based Product Manufacturing Company. Prog. Eng. Appl. Technol. 2023, 4, 913–922. [Google Scholar]

- International Labour Office. Guidelines on Occupational Safety and Health Management Systems: ILO-OSH, 2001; International Labour Office: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Tappura, S. The Management of Occupational Health and Safety: Managers’ Perceptions of the Challenges, Necessary Support and Organisational Measures to support Managers. Ph.D. Thesis, Tampere University, Tampere, Finland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Ligade, A.S.; Thalange, S.B. Occupational health and safety management system (OHSMS) model for construction industry. Int. J. Res. Eng. Technol. 2013, 2, 395–399. [Google Scholar]

- Mokoena, S. The Knowledge, Attitude, and Behaviour of Laboratory Workers at the National Health Laboratory Services Towards Health and Safety. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of Johannesburg, Johannesburg, South Africa, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, R.A. Improving Occupational Health and Safety in a Petrochemical Environment Through Culture Change. Doctoral Dissertation, North-West University, Potchefstroom, South Africa, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Karanikas, N. OHS Management Systems. 2021. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/357240470_OHS_management_systems (accessed on 10 August 2023).

- Esterhuyzen, E. Occupational Health and Safety: A Compliance Management Framework for Small Businesses in South Africa. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Brijlall, M. Analysis of Employee Participation in Occupational Health and Safety Activities in a Cement Manufacturing Organisation in South Africa. Ph.D. Dissertation, University of South Africa, Pretoria, South Africa, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Zyoud, W.; Qunies, A.M.; Walters, A.U.; Jalsa, N.K. Perceptions of chemical safety in laboratories. Safety 2019, 5, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carvalhais, C.; Dias, R.; Costa, C.; Silva, M.V. General knowledge and attitudes about safety and emergency evacuation: The case of a higher education institution. Safety 2023, 10, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahmani, H.; Ao, Y.; Yang, D.; Wang, D. Students’ evacuation behavior during an emergency at schools: A systematic literature review. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 87, 103584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, D.; Cui, L.; Huang, Z. A cellular-automaton agent-hybrid model for emergency evacuation of people in public places. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 79541–79551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovreglio, R.; Kuligowski, E. A pre-evacuation study using data from evacuation drills and false alarm evacuations in a university library. Fire Saf. J. 2022, 131, 103595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Constantine, A. ISO 45001:2018—Occupational Health & Safety Implementation Guide. Velika Britanija: NQA. 2018. Available online: https://www.nqa.com/medialibraries/NQA/NQA-Media-Library/PDFs/NQA-ISO-45001-Implementation-Guide.Pdf (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Rahmi, A.; Ramdhan, D.H. Factors affecting the effectiveness of the implementation of application OHSMS: A systematic literature review. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2021, 1933, 012021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lingard, H. First aid and occupational health and safety: The case for an integrated training approach. Burn. J. Int. Soc. Burn Inj. 2017, 111–117. [Google Scholar]

- Adisa, S.O. Framework to Improve the Safety of University Student Housing Facilities in the Western Cape Province, South Africa. Ph.D. Dissertation, Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Cape Town, South Africa, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Guest, G. Sampling and selecting participants in field research. In Handbook of Methods in Cultural Anthropology; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA; Plymouth, UK, 2014; Volume 2, pp. 215–250. [Google Scholar]

- Rahman, M.M.; Tabash, M.I.; Salamzadeh, A.; Abduli, S.; Rahaman, M.S. Sampling techniques (probability) for quantitative social science researchers: A conceptual guidelines with examples. Seeu Rev. 2022, 17, 42–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delvika, Y.; Mustafa, K. Evaluate the Implementation of Occupational Health and Safety (OHS) Management System Performance Measurement at PT. XYZ Medan to minimize Extreme Risks. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2019, 505, 012028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilusa, M.L.; Mogotlane, M.S. Worker knowledge of occupational legislation and related health and safety benefits. Curationis 2018, 41, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muthelo, L.; Mothiba, T.M. Strategies to Enhance Compliance of Health and Safety Standards at the Selected Mining Industries in Limpopo Province, South Africa: Occupational Health Nurse’s Perspective. Ph.D. Thesis, Univeristy of Limpopo, Polokwane, South Africa, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Orymowska, J.; Sobkowicz, P. Hazard Identification Methods. Zeszyty Naukowe. Transport/Politechnika Śląska. 2017. Available online: https://yadda.icm.edu.pl/baztech/element/bwmeta1.element.baztech-25bc7bd3-4f27-4c8e-84a2-9b35f4620aad (accessed on 1 January 2025).

- Letooane, M.K. Factors Impacting on the Quality of Work Life: A Case Study of University “A”. Ph.D. Dissertation, Durban University of Technology, Durban, South Africa, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Okechukwu, E.U.; Chizoba, A. Occupational health safety practices and employee performance in manufacturing firms in Enugu State. Contemp. J. Manag. 2022, 4, 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Aslam, H.; Almuhametov, I.; Sakhapov, A. Understanding attitudes towards emergency training modes: Conventional drills and serious games. In Proceedings of the Games and Learning Alliance: 8th International Conference, GALA 2019, Athens, Greece, 27–29 November 2019; Proceedings 8. Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 372–382. [Google Scholar]

| Year | 2021 | 2022 | 2023 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total number of incidents | 35 | 33 | 37 |

| Near-misses | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| First aid | 5 | 4 | 1 |

| Doctor cases | 4 | 5 | 9 |

| Disabling incidents | 24 | 22 | 27 |

| Fatalities | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Occupational disease | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mtikitiki, N.; Madonsela, B.S.; Maphanga, T.; Shale, K.; Grangxabe, X.S.; Baloyi, T.M. Occupational Health and Safety Management System of a South African University Setting. Safety 2025, 11, 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020034

Mtikitiki N, Madonsela BS, Maphanga T, Shale K, Grangxabe XS, Baloyi TM. Occupational Health and Safety Management System of a South African University Setting. Safety. 2025; 11(2):34. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020034

Chicago/Turabian StyleMtikitiki, Ntombenhle, Benett Siyabonga Madonsela, Thabang Maphanga, Karabo Shale, Xolisiwe Sinalo Grangxabe, and Tshidi Mokgatsane Baloyi. 2025. "Occupational Health and Safety Management System of a South African University Setting" Safety 11, no. 2: 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020034

APA StyleMtikitiki, N., Madonsela, B. S., Maphanga, T., Shale, K., Grangxabe, X. S., & Baloyi, T. M. (2025). Occupational Health and Safety Management System of a South African University Setting. Safety, 11(2), 34. https://doi.org/10.3390/safety11020034