Abstract

The article is a case study in family genealogy and genealogical methodology, focusing on the author’s reconstruction of the early history of the first members of the rabbinical Polonski family from Russia after they immigrated to the United States during the early twentieth century. Describing and analyzing the various sources used in the study of family genealogy, it shows how gender, lines of kinship, language, and timing can play an important role in explaining the dichotomy between oral family history and written documentation. It also relates to the pitfalls of dealing with genealogical issues without employing a rigorous and precise methodology. Dealing with issues of inclusion and exclusion in family narratives, it shows how these variables helped shape the family’s oral history, giving us insight into why certain family members appear and others disappear over time from various family narratives.

1. Introduction

Identity. The fact of being who we are. Social anthropologists speak of identity as a form of “selfhood”, combining immutable factors such as common ancestry and biological characteristics with more fluid forms of identification that change throughout one’s lifetime (Hitlin 2003). Historians and political scientists refer to identity as being “social” and “personal”, pertaining to both collective categories and sources of an individual’s self-respect and dignity (Fearon 1999). Most people embody a number of identities simultaneously: individual identity and perception of self, social identity and gender roles, collective identity, and a sense of belonging and community. It is that need for a sense of belonging that often compels people to examine their personal and individual identity in the hope of better understanding their lives and their choices. Despite sociologist and communication expert Karen Cerulo’s claim that one must focus on the “me” before one can address the “we”, there are times that one can only understand one’s personal identity by first delving into the past and present components of one’s collective affinity (Cerulo 1997).

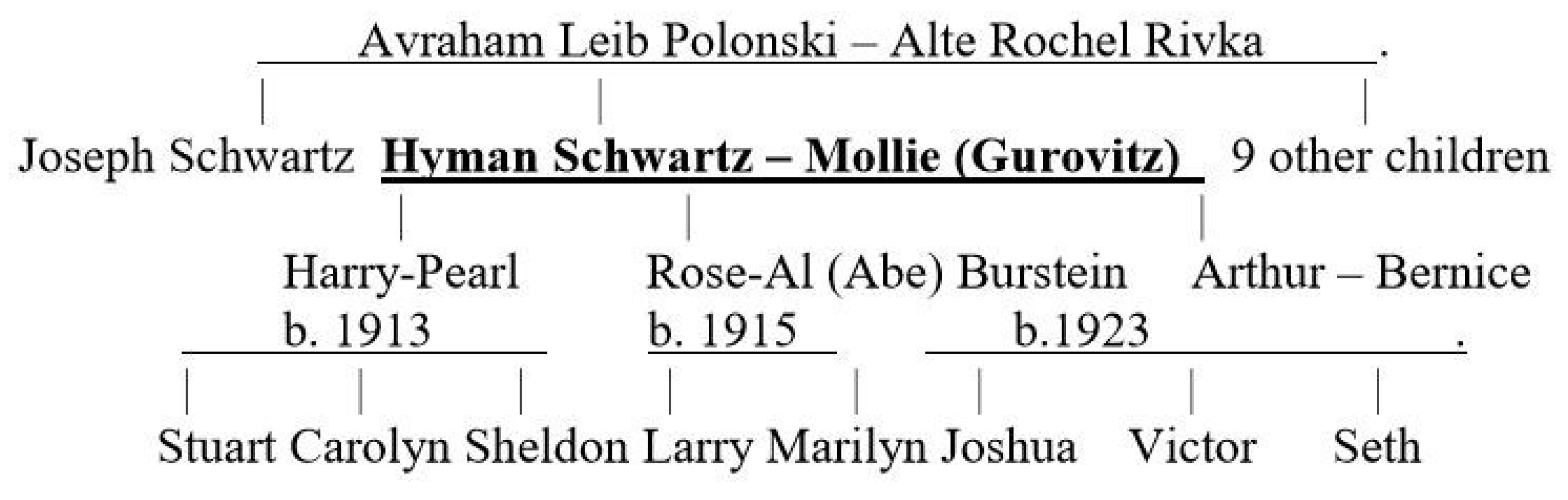

Identity and belonging were two of the elements that served as the impetus for a historical odyssey that I undertook during the spring of 2017 when I began to reconstruct my husband’s family history (Baumel-Schwartz 2017). Concentrating initially on my nonagenarian mother-in-law’s experiences and ancestry, with her assistance, I fleshed out stories about her side of the family going back four generations. The true mysteries, however, were from my late father-in-law’s side, of which my husband Joshua Jay Schwartz knew little. Josh had grown up knowing his paternal grandparents, Hyman and Mollie Schwartz, but had rarely heard them speak about their lives in Europe or their early years in America. Josh’s father, the late Dr. Arthur Schwartz, may have heard stories about those times from his parents, but had never passed them on to his children.

Although the book I was writing focused primarily on my mother-in-law’s family, at some point, I decided to include a chapter about the Schwartz side, taking up the challenge that my husband had thrown out over a decade earlier when in a candid moment he stated: “Who am I? I have no idea. Even my name isn’t my own, as my grandfather changed our family’s name when he came to America. How can someone build their identity when they don’t even have their own name? How can someone know they are, and to whom they belong, when they don’t really know their own heritage?!”

With those questions ringing in my ears, I set out to answer some of them by “unearthing” the lost “Polonskis”, the Schwartz family’s original name in Europe. This article deals with one part of my reconstruction, that pertaining to the first family members who set foot in the New World over a century ago. My investigation soon turned from factual to methodological. How could I explain the inconsistencies in family history between the oral and written sources that I discovered? Why was there a complete dearth of information regarding certain individuals, events, and family crossroads? Trying to make sense of these findings, I posited explanations that guided my research in new directions, reconnecting it to issues of identity and belonging which were among the salient questions that had propelled me on this journey in the first place.

The final results, a portion of which are encapsulated in this article, are a case study in family genealogy. Illustrating how “what we know” is intrinsically interconnected with “how and from whom we know it”, I show how factors such as gender, language, and timing can play an important role in determining whether and how genealogical information gets passed down from generation to generation. I also show some of the problems regarding what happens when genealogy does not carefully and responsibly utilize historical methodology when dealing with family reconstruction.

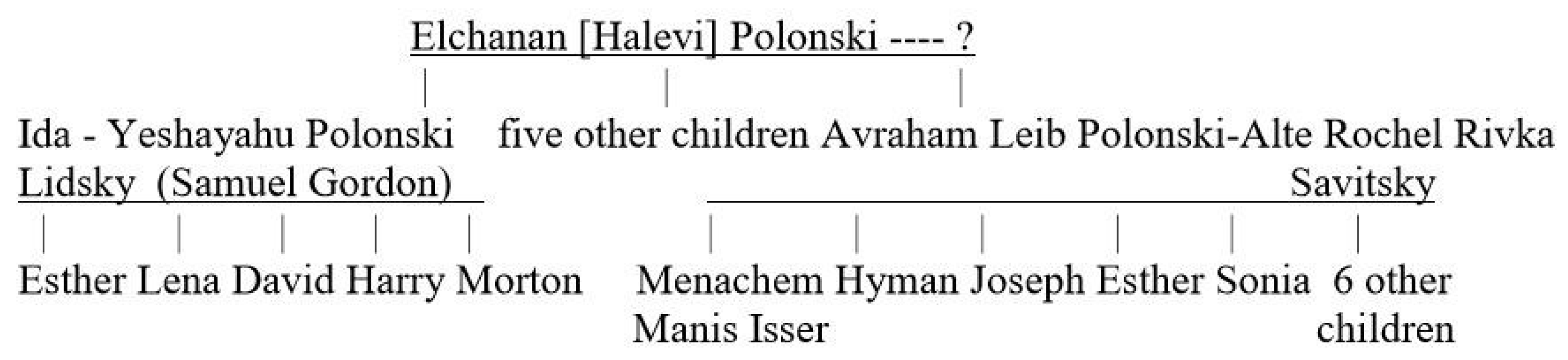

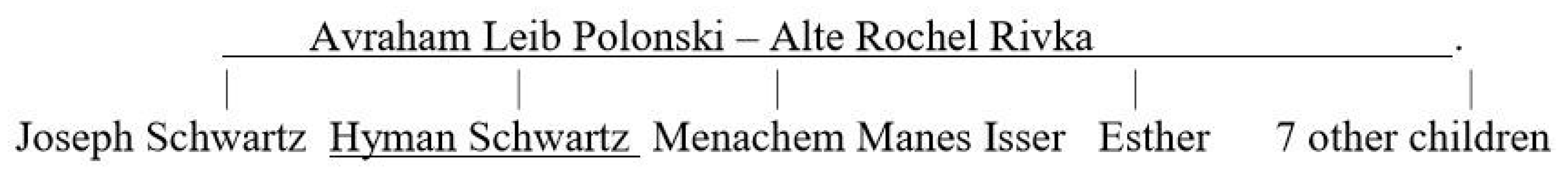

Our initial narrative centers around three personalities who composed the first generation of Polonskis to immigrate to the United States: Rabbi Yeshayahu (Isaiah) Polonski and his young nephews Joseph and Shimon Chaim Polonski, who all arrived in New York separately during the early 1900s. All were called “Polonski” in Europe, and we have written documentation of this fact. An example is Rabbi Yeshayahu Polonski’s rabbinical recommendation as practicing rabbi and ritual slaughterer dated 15 February 1900 (Hebrew date given in original 16 Adar I, 5660), signed by his brother, Rabbi Avraham Leib Polonski, rabbi of Dunalevici (Dunalevitch), and father of Joseph and Shimon Chaim, sealed with his official Hebrew/Russian stamp that states, “Avraham Leib Polonski in both languages”. As family names were determined in the Russian empire by the early 1840s, long before both Avraham Leib and Yeshayahu’s birth, they were born after their family adopted the Polonski surname.1 In addition, we know that Yeshayahu Polonski was later Samuel Gordon, as Avraham Leib’s son Shimon Chaim, by then Hyman, was in close family contact with his uncle in America. Furthermore, Gordon’s son Harry gave his father’s family documents (including correspondence between his father and his father’s brother Avraham Leib utilizing both last names, and Gordon’s rabbinical documents from Europe), to my husband’s brother (Hyman’s grandson), for safekeeping.

None of the three Polonskis who immigrated to America remained “Polonski” after their immigration, which is why the name in the title appears in quotation. However, those who came to America did not all choose the same new family name, a story in itself.

When I began my research, my husband Josh knew a few basic stories about Rabbi Yeshayahu Polonski and Joseph Polonski, had known the third figure, his paternal grandfather Shimon Chaim, quite well, and knew some of the descendants of all three men. Some of the stories were based on oral history; others on written documentation in the family’s possession. Initially, I began to flesh out these stories with documentary resources easily available online. During a second stage, I returned to the oral histories, this time widening the scope of those being interviewed. I then turned to written documentation in order to cross-reference a number of incidents I had been told in the interviews. Finally, I returned to both family documentation and oral sources to corroborate or negate genealogical claims about the family that had been raised during the initial reading of this article.

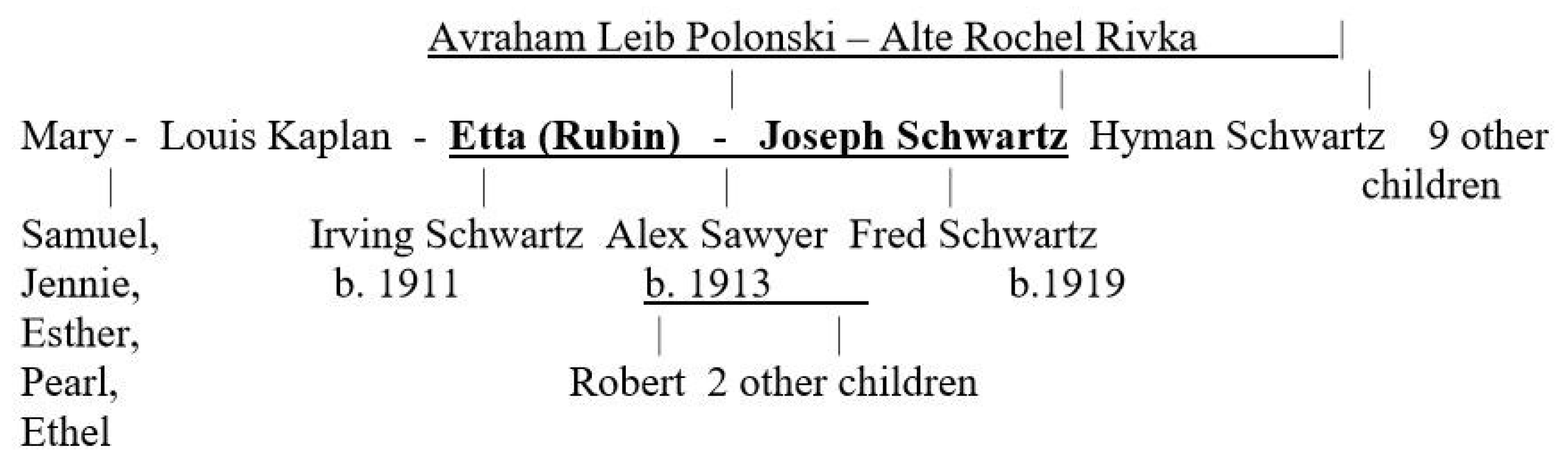

Some of the initial oral and written family histories had to do with names. We knew from family stories and correspondence (later corroborated by census records) that Rabbi Yeshayahu Polonski had adopted the name Gordon after leaving Europe, but were not sure why he had changed his name to Gordon. We knew that Shimon Chaim Polonski had adopted the name Hyman Schwartz in America and knew that there was a shochtim (ritual slaughterers) strike the day he arrived, but had no idea of his precise date of immigration. We knew that Joseph had also been called Schwartz, and my husband was unsure of whether he had later changed his name to Sawyer as one of Joseph’s sons used the family name Sawyer.

Then there was the oral history pertaining to geography. Initially, Josh claimed that the Polonski family was from Latvia, but was unsure whether there might be some Lithuanian connection as well. He knew the names of two towns—“Dunalevitch” and “Shventzenin” as he pronounced them, using the Jewish names of these towns—to which his family was connected, but was unsure of the nature of that connection. We knew from family stories, and particularly those of my grandfather-in-law, those of Rabbi Gordon’s son Harry who had been in close touch with my husband’s family, and from family correspondence, that Rabbi Gordon had been a Rabbi in Tarrytown, N.Y., but did not know exactly when he had moved there. We knew that Josh’s grandfather Hyman had settled in Nyack, N.Y., soon after getting married, and had lived in New York City before that time, but were unsure exactly where in that city he had resided before getting married. My husband remembered visiting his cousins—Joseph’s sons and grandsons, on a poultry farm in Lakewood, N.J., but he knew nothing about when they moved there and where they had lived prior to that time.

Finally, there were the oral histories pertaining to professions. We knew that Yeshayahu’s older brother, Hyman and Joseph’s father Rabbi Avraham Leib Polonski, had been a small-town Rabbi in Europe who had died of influenza sometime before 1923, as Josh’s father Arthur, born that year, had been named after him and Ashkenazi Jews were traditionally only named after deceased relatives. But we knew little about from whom Avraham Leib had received his rabbinical degree or where he had undergone his studies. We had been told that Hyman Schwartz was the seventeenth generation of rabbis in the family, but knew almost nothing about any of the others. We knew that Hyman had initially worked in the USA as a shochet (ritual slaughterer), before he opened a grocery store and later a liquor store, but had no inkling where he had received his religious training. We had heard that he was one of eleven children, with a brother Joseph who had immigrated to America, another brother, a well-known Rabbi, Rabbi Menachem Manis Isser Polonski, who had been killed during the Holocaust, a sister Esther who had immigrated to Palestine, and a younger sister Sonia who survived the war with her husband and daughter and came to America. Josh had known Esther and Sonia, and had heard about their brother the Rabbi and even met his children who had survived the war, but knew almost nothing about the lives and professions of Hyman’s other European siblings who perished during the Holocaust.

Then there were the second generation of Polonskis—none of whom had ever been called “Polonski”—in America. My husband had of course known Hyman’s children—his father and his father’s siblings, Harry and Rose. He also remembered Joseph’s children—Irving, Alex, and Fred. But unlike the case of his uncle and aunt, where he had grown up with their families, when it came to Joseph’s descendants, he knew little about their lives, and had only childhood memories of the grandchildren. Similarly, he had known one of Rabbi Yeshayahu (Polonski) Gordon’s sons, Dr. Harry Gordon, who had been medically helpful to the family at a particular juncture, but had never heard anything about any other children or grandchildren. This was not a question of persons “forgetting” family members, but rather of never having being told about them, or meeting them in the first place. Why had they all disappeared from the family narrative? Was it because they had not conformed to the accepted model of kinship relations? What could we learn from this about themes of family communication or the creation and erasure of family memories? Was this a case of salvaging the histories of family members who did not conform to traditional procreational norms of “blood kinship” (i.e., childless or single family members, or various types of blended intentional families) so that they would be more than a point of termination in a genealogical narrative?

For a historian of the ancient world, my husband knew lamentably little about his own family’s recent past, and was thirsty to know more. As a historian of the modern era who had already made genealogical forays into my own family history, I was more familiar with the relevant documentary repositories and the caveats when it came to the use of oral history.2 As I have done in all historical studies that heavily utilize oral history, such as my studies of women and gender during the Holocaust (Baumel 1998), here, too, I differentiated between different kinds of oral documentation and cross-referenced information from oral sources with written documentation where it was available. Where it was not, I made sure to cross-reference with other oral sources, preferably not from the same immediate family branch and from different generations.

When dealing with the American branch of the family, I also relied on written documentation from American sources, as my focus was reconstructing their lives from the time they came to America. Written European sources of primary documentation were utilized more to document the European side of the family, which is included in another study (Baumel-Schwartz 2017). The European-based documentation utilized in this case was primarily those documents found in family repositories which dealt specifically and unquestionably with the family members in question. I will refer to these documents later on in this essay.

With this relatively meagre knowledge of family history in hand, I decided to take up the quest for the lost Polonskis of Europe and the former “Polonskis” living in America, and unearth their stories to enable my beloved husband to discover his heritage. I may have not have been a Schwartz by birth, but I was tied to the family with unbreakable bonds that I had chosen to forge. And here we have the third element, in addition to identity and belonging, that was an impetus to the genealogical odyssey that I undertook during the spring of 2017. It was a labor of love.

2. Between History and Genealogy

The essence of this article is a case study in family genealogy. In his introduction to Genealogy’s inaugural edition, sociologist Philip Kretsedman chose to begin his article with a quote from the English moral philosopher Bernard Williams, who in his treatise Truth and Truthfulness, defines genealogy as, “a narrative that tries to explain a cultural phenomenon by describing a way in which it came about, or could have come about, or might be imagined to have come about” (Williams 2004, p. 20). By claiming that genealogists often fill in the gaps of past developments through the use of literary license and creative flights of fancy, Williams draws an implicit line between genealogists and historians, noting the methods that no serious historian would consider, at least until the advent of postmodernism. While there are genealogists who today consider this statement outdated, the phenomenon, however, still exists.

Does that mean that historians cannot be genealogists? They certainly can, as historical methodology is predicated on the goal of creating as precise a reconstruction of the past as possible before analyzing that past. Additionally, for those historians like myself who specialize in the modern contemporary history, we routinely utilize many of the sources that genealogists tap into in their work. But historians engaging in genealogy are of a different breed than genealogists who are not professionally trained in historical methodology. Returning to Williams, a historian’s goal is to put together as truthful a reconstruction of the past as possible, occasionally voicing speculations where source material may lag, but not promoting them as definitive sources to be used in building up further historical levels as some genealogists do.

Does that mean that genealogists cannot compose a truthful representation of the past? Of course they can, and often do it as well as historians, but it depends to a great extent on their methodology. Methodology is indeed the crux of the matter as a genealogical study is not just an aggregation of historical data, but also a method of explanation. Kretsedemas succinctly summarizes this point when he states: “The thing that is the most genealogical about a genealogy is the method by which its contents has been strung together” (Kretsedemas 2017a).

Methodology is one focus of the following pages, in which I analyze the methods that I employed in my genealogical case study of “unearthing” the history of the first Polonskis who immigrated to the United States. Not only is it a study in kinship and descent, which Bruce Knauft reminds us is the central discipline of anthropology (Knauft 2017), but it attempts to trace family pathways and investigate social identities, while carefully skirting what historians often view as the inherent danger in genealogical research: the use of powers of creation among genealogists to the point where they believe that past reality was whatever they chose to make it (Kretsedemas 2017b). I indeed came across an example of this while writing this article, and although it propelled me to further research the topic and find fascinating written and oral proof of what I had originally written, it highlights the dangers of genealogical conjecture without the use of firm historical methodology.

Consequently, I attempted to refrain from conjuring up out-of-context conjectures when running out of source material. Nor was I willing to accept all documentary sources—or lack of information appearing in certain documentary sources—at face value, in cases where they were known to be problematical and often imprecise. One that comes to mind is the passenger manifest lists of the Ellis Island website where information appearing in the lists, particularly the transcribed digitized ones, did not always match reality and was even transcribed incorrectly in various cases. If I was unable to tap into alternative sources, a brick wall remained, so when source material dried up, branches of the family tree remained unadorned and truncated. The following is a portion of what I managed to put together throughout the historical-genealogical journey of reconstructing the adventures, odysseys, and ultimate fate of a large portion of my husband’s family.

3. Results

3.1. Step One—Putting Together the Basics

How does one reconstruct the history of a family in which one did not grow up? By what means can one reassemble not just the structure, but the essence of a person about whom one had only heard of second hand, only recently, and at times, only via one possibly biased source? These are questions that every historian confronts, particularly those of us dealing with contemporary history on the professional level. After close to 40 years of historical writing, I certainly knew the answers to the questions posed above and have taught them to my students. But just as a doctor is exposed to a new perspective of their profession when they suddenly become the patient, so it was when I began researching my own family, and now my husband’s family, with all it entailed.

When I began my reconstruction of the American Polonski descendants—none of whom was actually called “Polonski” in America—I hoped that the process would be easier than when I reconstructed the European branch of the family. Not only were there people alive and easily available to me who had known some of them, allowing me to tap personal recollections, but unlike the European relatives of whom we knew very little, and for whom we had little documentation, they had spent the majority of their lives in the United States in easily accessed documentable frameworks. Other than using family correspondence from Europe, community memorial books, or certain online databases, for this portion of my research, there was little need for Russian archives as we already knew from family held documentation where the American family had lived in Europe before their immigration. I could therefore concentrate primarily on American documentation frameworks.

What were these frameworks? Their immigration particulars should supposedly be accessible through Ellis Island immigration records. Their marriages and deaths, if occurring in America, should be recorded in public records. Their places of domicile, professions, and household particulars should almost certainly appear in various census records from the first half of the 20th century that had already been released to the public. To simplify matters, many of these documents were now available online, making it unnecessary to leave one’s desk in order to conduct archival research. Then there were the family documents that were already in our possession: Hyman and his wife Mollie’s marriage license, Mollie’s ketuba (Jewish marriage contract), Hyman’s naturalization papers, and a few family documents including rabbinical recommendations written in Europe for Rabbi Yeshayahu Polonski (Gordon), with seals of local rabbis, including one by his brother, Rabbi Avraham Leib Polonski, and a letter which Avraham Leib Polonski in Europe had written to his brother in America, Rabbi Yeshayahu, mentioning Hyman, Joseph, and other family members.

Documents, however, often provide an incomplete and not necessarily correct historical family narrative. Incomplete, as they are often dependent upon sparse self- reported information, such as late 19th century and very early 20th century American immigration records. Not necessarily correct, due to self-reporting, truncated data, or erroneous transcribing of handwritten documents such as those of the Ellis Island immigration and American census records. I hoped, therefore, to tap into three additional and invaluable sources which might enable me to cross-reference information: recollections of extended family members, photographs, and tombstones. As Carolee R. Inskeep states on the back of her comprehensive volume, The Graveyard Shift, “visits to the grave site of a relative are perhaps the most enlightening research trip a family historian can make. Along with the vital information contained on headstones, a researcher is often rewarded with information that cannot be obtained in any other way” (Inskeep 2000).

3.2. Step Two—When Did They Immigrate?

My initial research addressed four questions whose answers, I hoped, would provide me with the basic framework of the Polonskis’ early lives in America. When did each family member immigrate? Where did they live? How did they earn their livelihood? When did they change their name? Two ways of finding the answer to the first question were to examine immigration listings or census records. As early 20th century census records noted one’s immigration date, the first question was ostensibly the most straightforward.

Two “Polonski”, three “Polonsky”, five “Polansky”, six “Polanski”, three “Palonski”, three “Polanska”, 116 “Gordon”, and two “Gorden”s arrived at Ellis Island in 1900, but none of them were Rabbi Polonski/Gordon and his family. Although it was suggested by a leading genealogist reading this article that Rabbi Samuel Gordon could have been “Schloime Gordon”, who immigrated to America on 25 May 1901 from Dunilewitz, Russia, on the steamship “Phoenicia”, this is certainly not “our” Rabbi Samuel Gordon. Not only is there no connection between the names “Schloime” (Solomon) and “Samuel”, but we have no evidence that Rabbi Gordon had abandoned the family name of “Polonski” before immigrating. There was indeed a large “Gordon” clan living in Dunilewitz, but there is no reason to think that Rabbi Gordon would have come from there, as all his rabbinical documents in our possession place him as living in Slonim, a major city in the Grodno district belonging to Russia before the First World War, while it was his brother Rabbi Avraham Leib who was Rabbi in Dunilewitz.

In addition, we have quite a number of documents indicating that the Gordon family immigrated in 1900. Census records from 1905 list Rabbi Gordon, his wife Ida, and their children Esther, Lena, and David as all being in the country for five years.3 The same holds true in the 1910, 1920, and 1930 census records, all listing the family’s immigration year as 1900.4 Rabbi Gordon’s daughter Esther’s (Gordon Peters) census record for 1930 also has her listed as immigrating in 1900.5 Census information was self-reported, but there was no ostensible reason for any of them to prevaricate on the matter of their immigration dates which do not change over a period of 40 years.

Then there is Rabbi Gordon’s front-page obituary in the Daily News of Tarrytown from 11 September 1933, whose headline states, “born in Russia, he was guiding spirit in villages since 1900”.6 The article also notes that he was the youngest of seven children, his father and brother were rabbis, and that they came to America via Argentina. While this last piece of information may have been written in error, the typesetter substituting “Argentina” for “Europe”, it raises the possibility that the family may not have entered the United States via Ellis Island, and could explain why they do not appear in its immigration listings. Finally, Rabbi Gordon’s death certificate from 1933 lists him as having been in the country for 33 years.7 The genealogical desire to “close the circle” and identify Rabbi Samuel Gordon with “Schloime Gordon” may be understandable, but it shows the pitfalls of what Bernard Williams hints to regarding how things “may have come about” when not using well accepted historical methodology.

Would I have better luck with the next family member? Possibly. Joseph and his wife Etta (Rubin) Schwartz first appear only in the 1920 census as they married in late December 1910, long after the census was taken. We know from their marriage license that they were living in Manhattan at the time of their marriage and like many unmarried young men, Joseph could have been living in a boarding house where only his last name might have been noted. There are quite a number of “Schwartz” male boarders from that year, undistinguishable from each other. We also know from the 1920 census records that Joseph and Etta are listed as having immigrated in 1904 and 1903, respectively.8

In an attempt to once again “close the circle”, the same genealogist who suggested that Samuel Gordon was actually “Schloime Gordon” now attempted to identify Joseph Schwartz and his brother Hyman as Chaim Palonsky and Joseph Palonsky, 17-year-old shoemakers, probably twins, who immigrated from Vilna and arrived in America on 8 July 1905 traveling to their uncle, Max Schwartz, and soon adopting his name as soon as they came to America. As proof, he noted that that Joseph lived next door to Max Schwartz in Brooklyn in the 1910 census. However, none of these claims hold up after a closer examination of the documents and of the family oral history.

Dozens of “Palonskys” immigrated to America. The name is not uncommon. A closer look at the ship’s manifest of the two arriving in July 1905 shows that Max Schwartz was Hungarian and single when these two nephews arrived in New York. As we know from various sources that Shimon Chaim and Joseph Polonski’s parents were both from Belarus, it is highly unlikely that they had an unmarried Hungarian uncle. Had Max Schwartz been married, it could have been his wife who was the aunt from Belarus, making him their uncle by marriage. However, Max Schwartz only married after his wife Ethel’s (Etta’s) immigration with her mother from Hungary in 1906.

In addition, as Shimon Chaim and Joseph’s mother’s name was Savitsky and as we know her lineage (a well-known rabbinical family), we also know that she had no brother named “Schwartz”, and her only brother lived in Lida and died there as a young married man. Returning to written documentation, “our” Joseph (Polonski) Schwartz married in late 1910 and during that entire year he was living in Manhattan and not Brooklyn. Hence a “Joseph Schwartz” living in Brooklyn next door to Max and Etta Schwartz on the 1910 census records is no proof that he was “our” Joseph. The name Schwartz, after all, is rather common.

Furthermore, there is no oral record in any branch of the family of Shimon Chaim and Joseph Polonski being twins, nor even being born a year apart. This was corroborated by several conversations with living descendants not only of Hyman and Joseph, but also with children and grandchildren of Hyman and Joseph’s numerous siblings. As one brought up, being a rabbinical family with twins is not a point that would have been “overlooked” or forgotten. Hyman never mentioned the fact to his children or grandchildren, nor did Joseph. In particular, it would have come up during discussions or descriptions of his bar mitzvah which would have been a twin one. Nor had anyone ever heard of any “Schwartzes” in the family before Joseph and Hyman. Finally, Joseph’s death certificate lists him as having been born in 1889, while we know that Hyman was born in 1885. These match the ages for Joseph and Hyman that the remaining siblings and other family members had also mentioned.9 Once again, we see the pitfalls of trying to close the circle without using historical methodology that includes careful and responsible utilization of written and oral documentation.

Who then was Joseph Polonski?

In 1904, seventeen “Polonski”, eleven “Polonsky”, six “Palonsky”, four “Palonski”, five “Polansky”, and eighteen “Polanski”s immigrated to America. The closest match was an unmarried “Josse Polansky” who had indeed immigrated in 1904, but was he our “Joseph”? Listed as being twenty-three and a merchant from Grodno, he was far from the fifteen-year-old which he would have been at the time. However, it is well known that younger immigrants often listed themselves as being several years older than they actually were to avoid immigration difficulties. He, and another young man of twenty-eight with a different last name, were traveling to an uncle named “Polonsky”, who was listed as living on Rivington street on the Lower East Side of New York. Why would Joseph have been living in Grodno? Could he have been studying there? Could it have been the other nephew’s dwelling place that the immigration authorities copied twice? Had “Josse” listed it in order to safeguard himself from being identified by the Russian authorities as many immigrants did while escaping army service? The mystery deepens when we look at the handwritten immigration records that show both young men listed as coming from “Melcheff”, which was crossed out with Grodno written above. Who was this uncle on the Lower East Side of whom family lore has no recollection? Could Joseph had not known of his uncle Yeshayahu’s name change and change of dwelling and listed his first address in America? Or could this be another Polonsky relative? These questions remained unanswered.

And what of our third protagonist? Hyman and Mollie (Gurovitz) Schwartz first appear only in the 1920 census which states that Hyman immigrated in 1906 and Mollie in 1907.10 He, too, could have been living in a boarding house in the Lower East Side during the 1910 census as we know from his 1912 marriage license that he lived in that area prior to his marriage. Hyman’s immigration date was further confirmed by stories he told in which he stated that he had left Russia around the time of the Russo-Japanese war (1904–1905) in order to avoid being drafted into the Czar’s army. When he left Europe, Hyman was named Shimon Chaim Polonski, as per his father’s letter to his uncle Samuel Gordon in our possession, containing the full family name. By the time he married in 1912, he was already “Hayman Schwartz”, as listed on his marriage license.

Early 20th century immigration records showed ten “Simon Polanski”s, five “Chaim Polonski”s, one “Chaim Polansky”, and one “Chaim Polanski” reaching New York. In 1906, a “Chaim Palonsky”, a “Chaim Polanski”, and a “Chaim Polonski” immigrated to America, but none precisely fit his personal details. The first came as part of a family group and is certainly not the man in question. The second was twenty-year-old Chaim Polansky, a tinner from Ostrowo, Russia, who had sailed from Rotterdam, arrived at Ellis Island to join a cousin in Paterson, New Jersey, and arrived on 18 April 1906.11 The third was twenty-three-year-old Chaim Polonski, a clerk from Rotnislowka, Russia, who had sailed from Liverpool, and arrived at Ellis Island on 14 December 1906 to join a cousin on Essex Street, N.Y.12

Shimon Chaim Polonski was neither tinner nor clerk, and from his father’s letter to his uncle, he was born and raised in “Dunalevitch”, the Jewish pronunciation of “Dunilovici”, a town in the Vilna Province of Russia now in Belarus,13 where his father served as rabbinical functionary for over 40 years, (Svirsky 1956) and was around 21 at the time of his immigration. We know of no cousins in Paterson, nor of family on Essex Street, but one clue, an inscription on the back of a small family portrait, points to the fact that the Chaim Polansky who arrived in April 1906 is possibly our man.

When I began researching family history, my mother-in-law gave me a cameo of her father-in-law’s mother, Alte Rochel Rivka Polonski, in a small frame. When my curiosity got the best of me, I pried the original picture from its frame, and found a Yiddish inscription on the back: “a memento for my beloved son Shimon Chaim Schwartz 1905–1926, Alte”. Why 1905? Shimon Chaim must have left home at the very end of 1905 on his way to the United States. Bearing in mind the travel difficulties of those years, he would have arrived in New York during the early months of 1906, several months after parting from his parents in Dunilovici. The 1926 date was most likely when the picture was taken, or sent to the United States. Hence it is more likely that the Chaim Polansky who arrived in April 1906 is the family member in question than the immigrant of December of that year.

3.3. Step Three—Where Did They Live? How Did They Support Themselves?

Where did the “Polonskis” live after immigrating to America? What do we know about their professional life at the time? Here again I turned to census records, personal documents such as marriage licenses, family recollections, and even obituaries. Unlike most immigrants who got off the boat in New York and ended up staying there for years, or for their entire life, it appears that Rabbi Yeshayahu Polonski did what certain religious functionaries coming to America did in order to make a living: he quickly found a position as a Rabbi outside the city shortly after his arrival, in his case, in Tarrytown, N.Y.14

From other sources, we learn that apart from being the Rabbi of the Tarrytown Hebrew Congregation, he was actually the local shochet at Guttman’s kosher butcher shop on Cortland Street.15 His death certificate also lists him as “Rabbi” and “Kosher Butcher”. Ida may have returned to family in Brooklyn to give birth to Harry, her first American-born son, as the New York Times obituary for Harry states that he was born in Brooklyn (Fowler 1988). But by 1905, the family was long living in Tarrytown in Westchester County. The various census lists also tells us about the head of the family’s profession. In the 1905 census, Gordon is listed as “Rabbi” with the word “clergyman” appearing next to it.16 In 1910, the Rabbi is listed as “Minister” with his place of work being “gospel”.17 Was this his own self-reporting or was it the census enumerator’s interpretation of the Rabbi’s explanations? We will never know, but it is more likely the enumerator’s interpretation as it is less likely that a European-born and trained Rabbi would list himself as “Minister”. Two years later, when he officiated at his daughter Esther’s wedding in Tarrytown, Rabbi Gordon listed himself as “Reverend”.18 By the 1920 census, the family had a fifth child, Morton (b.1913), and there the Rabbi is listed more precisely as “Rabbi” working in a “synagogue”.19 Family lore states that he actually earned his living more as a house painter than as a Rabbi, a telling fact about the need for Rabbis in early 20th century Tarrytown.

The family continues to appear in the 1930 census records, by which time only one son, “Mory” age 17, was living at home. At the time, Samuel Gordon still functioned as a Rabbi, Ida was a housewife, and they owned their own home at the time which was listed as being worth $8000, the equivalent of a bit over $112,000 in 2017.20 Samuel Gordon passed away suddenly of a heart attack in the early morning hours of 9 September 1933 in Ida’s arms. Buried later that day in the Tarrytown Jewish Community’s section at Mt. Hope cemetery at Hastings on Hudson, his simple tombstone reads: “Rabbi Samuel Gordon 1933–1975”, under which the Hebrew words “Harav Yeshaya’” (Rabbi Yeshayahu) appear.21

What happened to the family afterwards? Ida appears in the 1940 census as a widow living in Tarrytown with her youngest son Mordechai H. Gordon, who was a public school teacher.22 Her daughters were long married and her other sons no longer lived in Tarrytown. Ida outlived her husband by a quarter of a century and was buried next to him at Mt. Hope Cemetery in January 1958. But even after Samuel’s death, family ties between the Schwartz and Gordon families were not lost—at least one of the Gordon children reenters our narrative during the 1960s.

Early in that decade, Rabbi Gordon’s son, Dr. Harry H. Gordon, a pioneer in baby care and child development, returned to New York City after practicing medicine in Denver and Baltimore, and became the Dean of the Medical School at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine. Harry was the only Gordon child who remained part of the Schwartz family lore, and his medical connections were instrumental to Hyman Schwartz’s family at several junctures. During his stay in Baltimore, Harry Gordon was in touch with Arthur and Bernice Schwartz, who were living in Hyattsville, Md., for a short time. After his return to New York, he maintained contact with the extended Schwartz family until his death in 1988.23 Shortly before that date, Harry Gordon gave my husband’s youngest brother, Prof. Seth Schwartz, the correspondence between his father Rabbi Samuel Gordon and Rabbi Gordon’s brother, Rabbi Avraham Leib Polonski (Seth’s grandfather), from the early 1900s, along with additional family documents from that period, to which I refer to here.

These documents include several rabbinical documents, including rabbinical recommendations for Rabbi Gordon written in his European hometown of Slonim, and another from his brother Rabbi Avraham Leib Polonski, all of which have rabbinical seals (including one with Rabbi Avraham Leib Polonski’s surname written in Russian and Hebrew) and include reference to Rabbi Gordon’s lineage, mentioning his father and that of Avraham Leib: Rabbi Elchanan Polonski.

Who was Rabbi Elchanan Polonski? No mention of him appears in family oral history other than his name on these documents as being the father of Rabbi Gordon and Rabbi Avraham Leib Polonski. We know that he lived in Slonim as Rabbi Gordon’s obituary states that he was born in Slonim, was the youngest of seven children, and that his father and brother were also Rabbis. This matches additional documentation we have found in memorial texts written to commemorate Avraham Leib’s oldest son, Rabbi Menachem Manes Isser, where it is stated that he came from a line of Rabbis and includes a mention of his father and grandfather. (Lewin 1972). The Belarus revision lists of 1834 and 1850 include three Khonon (Elchanan) Polonskys living in Slonim, but there is no way to determine definitively if any of them are our man in question.24

And what of the two younger men? Where did they live and how did they support themselves? We also know little about Hyman and Joseph’s relationship with their family in Europe or the USA during the immediate years after their immigration. However, documents charting family events of the early part of the next decade flesh out part of the story.

The first are Joseph’s marriage records from late December 1910 that list various particulars of his life. At the time, Joseph was living on the Lower East Side and worked as an operator in a cloak shop, which was likely his domicile and profession since soon after his immigration, similar to hundreds of thousands of immigrants of those days who arrived at Ellis Island and remained in New York City, often earning their livelihood in the garment industry. On 26 December 1910 he married Etta Rubin, daughter of Rabbi Max Rubin and Fannie Freeheim,25 and the couple moved to Brooklyn where their three sons, Irving (b.1911), Alexander (b.1913 and named for his great-grandfather, Rabbi Elchanan Polonski), and Fred (b.1919) were born. All appear on the 1920 census as still living in Brooklyn.26

From that point on, the story as we knew it before this study became blurred. My husband and mother-in-law recalled visiting the family on a chicken farm in Lakewood, New Jersey, during the 1950s, but little before. To learn the rest of the story, I spent several days sleuthing the internet, checking death records and obituaries until I found reference to Alexander’s son Robert Sawyer, whom my husband remembered as a young boy. Having found his phone number, we made contact and heard the continuation of Joseph’s family saga. According to Robert, at some point in the early 1920s, the family moved to Tarrytown, N.Y., but he had no idea why they moved. It became clearer to him when I told him that there were already relatives living there—Rabbi Samuel (Yeshayahu) Gordon and his family.

Soon after the family moved, tragedy struck. Joseph suddenly passed away in the early 1920s, and Etta supported the family by running a dry goods store. Robert then told us that in 1947, Etta and her two younger sons, Fred and Alex, had bought a poultry farm in Howell, New Jersey, which they ran until the late 1950s. At that point, the farm was sold and the families moved to Lakewood.

Where did the name “Sawyer” come from?, we asked him. Having begun to work for a U.S. branch of a German firm as a chemist, Alex wanted a more American name then “Schwartz” (shades of his father Joseph who half a century earlier had obviously thought that “Schwartz” was more American than “Polonski”!) and changed his name to Sawyer (“he tossed a coin between Shaw and Sawyer and Sawyer won”27), while the other brothers remained Schwartz. Joseph, needless to say, had been Schwartz until his death.28

But when exactly had that death taken place? No one in the family could answer. When pressed, my mother-in-law realized that she had never met Joseph, and only knew his widow, Etta. Joseph’s grandson had never asked his father about it, and as his grandfather had died when his father was a young boy, his father had also known little about his own father’s history that he could impart to his children. My husband’s grandfather Hyman Schwartz certainly knew his own brother’s yahrzeit (date of death) as he would have sat shiva, the obligatory week of mourning, for him, and recited Kaddish in his memory, but no one alive today had ever spoken to him about the precise date.

The only resource left was to look for documentary corroboration. Initially, I looked through census documentation which once again fills in some of the gaps. The New York State Census of 1925 has an Etta Schwartz listed as living in Greenburgh, Westchester, the same area as Tarrytown, where she is noted as being head of the household, with her sons living with her.29 We therefore knew that Joseph died sometime between 1921 and 1924. An examination of New York State online death record indices shows that a Joseph Schwartz died in Tarrytown on 9 November 1922. As he was the only Joseph Schwartz to die in Tarrytown between 1920 and 1925, he appears to be our man. This is confirmed by his death certificate which lists his father as being Abraham and his mother as being Alte Savitsky.30

What happened to the family after Joseph’s death? The family could not be traced in the 1930 census, but appears again in Tarrytown in 1940, this time under a different name: Alex and Fred Schwartz were now listed as the 21 and 27-year-old stepsons of Louis Kaplan, a 52-year-old Russian-born butcher and their mother Etta Kaplan, living on Cottage Place. They, in turn, lived next door to Samuel Kaplan, Louis’s son, and his family, and a few houses down from Ida Gorden and her son Mordechai.31

When did Etta remarry? How long did her second marriage last? Why did Louis Kaplan disappear from the family narrative? Was it because he did not conform to traditional procreational norms of “blood kinship”? After asking Etta’s grandchildren pointed questions about him, it appears that his disappearance stems more from the fact that he did not conform to accepted marital norms. Louis and Mary Kaplan and their five children lived in Tarrytown, two houses down from Rabbi Samuel Gordon on Cottage Place.32 In September 1935, 47-year-old Mary passed away and soon after, Louis married the late Rabbi Gordon’s niece by marriage, the widowed Etta Schwartz. Tarrytown Jews often married other Tarrytown Jews, as is seen by Rabbi Gordon’s oldest daughter Esther who in 1912 married Abraham Peters, also a neighbor from Tarrytown.

It appears, however, that Etta’s second marriage was very unhappy and brief. As it did not conform to accepted marital norms, only those who lived through that period with Etta, or her immediate family, knew of the marriage.33 It was also never spoken about after Louis was no longer part of the family. Thus, other than Etta’s grandchildren who had heard of the brief interlude from their parents, no one marrying into the family or born into it after the mid-1940s ever heard of Louis Kaplan.34 This could also explain why Etta decided to move with her sons to a poultry farm in Howell in 1947, when she was in her 50s. Not only was she going into business with them, something that would solve some of her financial needs, but in view of the fact that other members of the Kaplan family lived near them in Tarrytown, it would be good to leave the town in general.

Hyman Schwartz was the easiest to trace as he often told his children and grandchildren about his momentous first night in the New World. When he arrived in New York as Shimon Chaim Polonski, there was a strike of ritual slaughterers and the immigrants were greeted at the pier by Jews asking whether there were any ritual slaughterers among them. Hyman, who had been trained in Europe as a shochet and carried his tools with him, answered in the affirmative. He was then taken to a warehouse on the Lower East Side where he was put to work as an unwitting scab, beheading chickens all night long during his first night in America.

Not particularly enamored with the sight of chicken blood in spite of his training and supposedly chosen profession, Shimon Chaim remained on the Lower East Side looking for a new job, and soon found work in a local feather factory making quilts stuffed with chicken feathers. As previously stated, he does not appear in the census records from 1910, but he obviously lived on the Lower East Side because sometime at the beginning of the second decade of the 20th century, he met Mollie Gurovitz (Horowitz), a young immigrant from Russia who lived on the next block. The two were married in Mollie’s apartment on Saturday night, 8 June 1912. As stated by their marriage license and Mollie’s ketuba, she was the daughter of the late Hirsch Zvi Hacohen and Slava Gurovitz from Russia.

From this point onwards, Hyman and Mollie’s family history is an integral part of the family’s oral history and required little need for genealogical sleuthing. Hyman Schwartz liked chicken feathers about as much as he liked chicken blood, and working conditions for ritual slaughterers in New York City were scandalous in those days. He therefore accepted a suggestion made by his uncle in Tarrytown, something corroborated in the letter that Avraham Leib Polonsky wrote to his brother, Samuel Gordon, and moved to Nyack in Rockland County, across from Tarrytown, to be a shochet and Hebrew teacher.”35 Quickly realizing that Nyack was in little need of a religious functionary, he and Mollie opened a grocery store to support their family, Harry (b.1913) named for Molly’s father Hirsch Zvi, Rose (b.1915) named for Hyman’s maternal grandmother Shayna Raizel, and Arthur (b.1923) named for Hyman’s father Avraham Leib.

Like his cousins, Rabbi Gordon’s children, and his brother Joseph, Hyman and Mollie kept a traditionally kosher home, but as there was no Orthodox community, they joined the local Conservative Temple and Hyman only reverted back to Orthodoxy in his old age when he resided in an Orthodox Senior Facility. Religious daily praxis notwithstanding, throughout his years in Nyack, Hyman remained somewhat of a religious functionary in his Temple, helping to conduct services and reading the Torah on the Sabbath and holidays (Froncek 1991, p. 20). Physically, Hyman and Mollie Schwartz may have lived in Nyack, but culturally they lived in a Yiddish-speaking world. Like many of the town’s Jewish immigrants, throughout their lives, the older Schwartzes continued to speak Yiddish to each other and to their children, who answered them in English and only had a passive knowledge of the Yiddish language. Sheldon Schwartz recalled his father Harry’s reluctance to speak Yiddish which he understood well, and attributed it to possible embarrassment that after so many years in the United States, his parents were still so “greenhorn-like”.36

3.4. Step Four—Why Do Immigrants Change Their Names?

The family may have been “greenhorn-like” linguistically, but obviously did not want their names to reflect it, as all three branches of the Polonski family in America changed their names soon after immigrating. When, however, did they take this step and why did they choose the names they ultimately adopted? This is the one question for which we have only partial answers.

We know that by the 1905 census, five years after his immigration, Rabbi Yeshayahu Polonski was known as Samuel Gordon, but have no documentation as to the precise date when he changed his name. Why did he choose the name “Samuel Gordon”? The name “Yeshayahu” was obviously foreign, while “Samuel” was more melodious to the ear of an English speaker. Was “Samuel” his middle name? No such middle name is mentioned in his European documentation, such as the certificates from Slonim stating him to be a Rabbi and ritual slaughterer, but that does not preclude that it exists. “Polonski” was also an obviously foreign surname, while “Gordon” could definitely be considered more American. Records show large numbers of “Gordons” living in Slonim, but we know that it was not a family name from his wife’s side, as Ida’s maiden name listed on their daughter Esther’s marriage license is Lidsky, and on Samuel Gordon’s death certificate as Haskin (which was also their son Harry’s middle name).37 There were, however, a large contingent of “Gordons” living in Tarrytown in 1905, with some even listed on the same census page and living on the same street as the Rabbi and his family. Could he have taken the name from there? We do not know.

The same lacunae exist with regard to his nephews Joseph and Shimon Chaim. Hyman often told his children and grandchildren that he had changed his name because of a suggestion made to him by an official at Ellis Island who said that the name “Polonski” would be difficult for Americans and suggested that he use the name “Schwartz”. There was no reason for Hyman to have invented this story. And if he indeed made the decision to adopt the name, then it was Joseph who followed. The Ellis Island story can also explain why the two did not choose “Gordon” as their uncle did. For years it was a family joke among his grandchildren, that if “Shimon Chaim Polonski” didn’t want to be identified as a Jewish immigrant, he could have done better than to have listened to the official who suggested that he change his name to “Hyman Schwartz”, an equally Jewish moniker of that time.

Our earliest written documentation of the use of the name “Schwartz” is in December 1910, where Joseph is listed as “Schwartz” on his marriage license. A year and a half later, when Shimon Chaim Polonski was married in June 1912, he too was listed as Hyman (or Hayman, as per his wedding license) Schwartz. In his letter to his brother from mid-1912, Avraham Leib Polonski (whose signature includes his last name, “Polonski”) writes about his sons in America, only mentioning Shimon Chaim by first name. By the time she wrote a dedication on the picture she sent her son in 1926, Alte Rivka Rochel Polonski already refers to her son as Shimon Chaim Schwartz. By then, obviously the change of surnames among former “Polonski” family members in America was already deeply ingrained into those remaining in Europe, and thus the new name appears not only on envelopes sent to America, but already on personal dedications.

The search for the American former “Polonskis” was only one part of my family odyssey. The other part involved looking for the European branch of the Polonski family, the story of Hyman Schwartz’s brothers and sisters, and any of their living descendants which I have detailed elsewhere (Baumel-Schwartz 2017). Of the eight Polonski brothers and sisters who reached adulthood, I eventually discovered the details of the four who had been murdered by the Nazis, one who survived the Holocaust in Europe and later immigrated to America, and one who had immigrated to Palestine in the 1920s. At the same time, I also learned a few details about previous generations of the family which had bearing on the question of where the three Polonski men who had moved to America had received their religious training.

A source mentioning the oldest Polonski sibling who had been murdered in Europe, Joseph and Hyman’s brother, Rabbi Menachem Manes Isser Polonski, states that his father, Rabbi Avraham Leib Polonski, had studied at the Yeshiva (religious studies academy) in Volozhin (Lewin 1972).38 In view of the common tradition at that time to send family members to study at the same institutions, there is a good possibility that Avraham Leib’s brother, Rabbi Yeshayahu Polonski, may have received his rabbinic training there as well.

Several additional sources detail Rabbi Menachem Manes Isser Polonski’s education, some of which took place at a new Yeshiva that had opened in the Lithuanian town of Lida, today Belarus (Feigmanis 2006; Lewin 1972). From the fact that his brother Hyman had come to America as a shochet, and was supposed to also have had rabbinical ordination, there is a good chance that he studied there not long after his brother. Familiar with the ways of the New World, Rabbi Yitzchak Ya’akov Reines, founder of the Lida Yeshiva, was known for sending his students immigrating to America with letters of recommendation asking to help the young man in question earn his livelihood.39 Knowing how difficult it was for a Rabbi to find a job in early 20th century America, he would ask to find the bearer of such a letter a position as a shochet, a fundraising emissary for the Lida Yeshiva, or possibly even as a vendor of lottery tickets, which he had heard was a lucrative business in America! (Robinson 1907, pp. 81–82). Having tried his luck as the Nyack shochet, Hyman Schwartz, it appears, ultimately preferred running a grocery store and later a liquor store, rather than being an emissary or vendor of lottery tickets.

4. Discussion: Putting Together the Pieces

Looking back at my reconstruction of the former “Polonski” family in America, I appear to have made significant progress from my starting point. We now knew when the heads of each of the three former “Polonski” families in America had immigrated to the United States, where they lived, how they earned their living, and had a general time framework of when they had changed their names. We knew who many of them, and their children, had been named after, enabling us to reconstruct earlier generations of the family. Equally important, during the reconstruction process, we made contact with a number of long-lost family members and discovered new ones of whose existence we had barely known. In one way or another, these contacts continue until today, giving a broader and richer dimension to the term “family identity” than that which existed before this process began.

But there were still several gaps. We did not know why Rabbi Yeshayahu Polonski chose the name Samuel Gordon. We could not definitively find any of the three Polonskis on the Ellis Island website, although we managed to locate a possibility for both Hyman and Joseph. Census documents had told us about Etta Schwartz’s remarriage which no one in the family had ever mentioned. Only after finding it and asking pointed questions of her grandchildren did we learn why it did not become part of the family’s oral history. Harry Gordon had remained in touch with the family and had even given my brother-in-law some of his father’s family documents, but what of his siblings or other members of his family? Why had no one remained in touch with them? If information about the family’s history had been known to the immigrant generation which reached the United States, had it been passed down to any of their children, and if so, why had their children not passed any of it down to the next generation?

These questions lead me to reexamine the process, methodology, and sources that I used throughout this genealogical odyssey and note how they relate to the issues of kinship relations and family pathways. Written sources of various issues may never have existed (why and when had people changed their names) or were difficult to locate (burial information; tombstones), but why was the family’s oral history lacking the answers to what were in most cases very basic factual questions? It is very easy to say “people forget", but when there are quite a number of people to ask, and none have heard of a particular issue, it nevertheless raises questions. Why is X forgotten while Y is not? Therefore, it seems that there were a number of factors that came into play in trying to make sense of the initial family history before I attempted this reconstruction.

The first factor is language. Like many Jewish immigrants of the time, the first generation of Polonskis in America were Yiddish speakers, with a working knowledge of English. They would speak to their children in Yiddish, and although most children either spoke the language or were fluent comprehenders, they usually responded to their parents in English. The third generation, the immigrants’ grandchildren, usually knew little or no Yiddish. As the older generation aged, they began to revert back to Yiddish and their English got more limited and shakier. Consequently, most of the grandchildren rarely had long conversations with their grandparents on matters of note. And as it is frequently grandchildren, more often than children, who converse with their grandparents about family history, the language barrier made this a rare, if not totally absent, occurrence in the greater Schwartz family. Kinship relations and even the desire to pass on information may have existed, but technical issues such as linguistic ability limited the possibility of imparting family stories to the third generation.

A second factor is gender. Traditionally, women have often been responsible for the social aspect of family connections, including the maintenance of family pathways, and this is particularly true in many immigrant families.40 These include the cultivation of family ties, decisions regarding issues of inclusion and exclusion of various family members, and often, even transferring family memories to future generations. In all three cases, the Polonski immigrants were men, one of whom already came to America with a wife and children, but as was often customary among traditional Jews of the time, the ties were primarily between those who shared blood See (Soyer 2002). With Joseph’s death, the ties continued between Hyman, Mollie, and Etta, and then to a lesser degree between Hyman’s sons and Joseph and Etta’s boys. As Hyman’s wife Mollie was known in the family as being rather taciturn and shy, the family pathway remained a primarily male territory, and thus, circumscribed to a degree. The same held true for the relationship between Hyman and his uncle, Samuel Gordon. That relationship continued into the next generation with Hyman’s cousin Harry Gordon, who then maintained a relationship with Hyman’s son Arthur. When I asked my mother-in-law about any relationship with Harry’s siblings, she recalled that at one time her husband had met Harry’s younger brother Morton who had lived nearby. But the relationship was not sustained, possibly because it was a male venue. Without women to cultivate the relationships, many remained circumscribed or superficial, and did not continue on for an additional generation.

A third factor is timing and mortality. Joseph Schwartz passed away at the age of 33 and his young sons did not have much opportunity to learn directly from him about the Polonski-Schwartz family history. Thus, they had little they could pass on to their own children on this matter. As the grandchildren on that side never knew their grandfather, they could not hear any stories directly from him. Similarly, Harry Schwartz, Hyman’s oldest son, may have had memories of Joseph’s death which occurred when he was about nine, but he never passed on any of these stories to his children. As for the more common passage of memories and family stories to one’s grandchildren, here there was no language barrier, unlike that which existed between Hyman Schwartz and his grandchildren. However, Harry died in his fifties, before his grandchildren were born, and did therefore not pass on any stories directly to them.

Why were there no family memories of Etta’s second marriage? Was it because it did not conform to the stereotypical conventional lineage of husband-wife-children? Possibly, but it might possibly also be an issue of timing and mortality and its effect on oral history. By the time I began trying to reconstruct family history, there was no one alive who remembered Etta’s second marriage from personal memory. Her children had passed away and her grandchildren knew very little of the story other than it was a brief, unhappy marriage before they were born. My mother in law, who joined the family in 1950, knew Etta as being Joseph’s widow. Thus, this episode of family history was relegated to the past, and had it not been for census documentation, would have been altogether overlooked.

The last factor is one of awareness. How many people are truly aware of the fact that if they do not ask their parents (or grandparents and other older family members) about their family’s past, there is no guarantee that there will still be someone to ask if they become interested in the answers sometime in the future? Time and again while trying to figure out various family permutations, I asked my husband a question to which he answered, “I have no idea, I never asked”. When dealing with modern genealogy, this is maybe the most important lesson one can learn from such attempts to reconstruct family history: to ask older family members questions about their past and to record their family recollections, beginning with the most basic issues of “when”, “where”, and “why”. These are all simple but significant questions which can ultimately provide the necessary chronological and geographical guidelines to stories which can be fleshed out later.

5. Conclusions

To close a circle is to return to the beginning, something I shall do here as well. What can our genealogical foray teach us about social and personal identity? In what way does understanding the “we” help us better understand the “me”? How do the compelling components of the Polonski family lineage that I discovered extend into a better comprehension of later social and cultural family contexts? And finally, to what degree do the fragments of the past that I unearthed assist us to better conceptualize the present?

My exploration of the genealogy of the Polonski family in the United States is in effect a case study of the changes that take place in social and personal identities of immigrants. As Beverly Nann has shown us in her study of immigration adaptation and resettlement, with few exceptions, the immigration process begins with a period of uprooting which is both physical and psychological. Immigrants often go through a rural-urban adjustment if they have come from small towns. In many cases, this is followed by a stage of culture shock when facing the challenges to their traditional values and way of life as they encounter the new society in which they now live. The loss of familiar social support requires immigrants to find alternative support systems, familial, communal, or other, to help them during their period of integration. There is often a change in in their economic and social status, not always to the better, at least at the outset, and they risk facing discrimination and intolerance when they leave the boundaries of immigrant society (Nann 1982, p. 87).

Quite a number of these factors affected the former “Polonski” family. Following their immigration, the social identity of the various family members underwent predictable changes, first and foremost as a result of having left their European families and communities. They were indeed physically uprooted, primarily by choice, both to escape persecution and to better themselves, but we know very little about the psychological impact of their losing their European roots. Having lived in a semi-rural setting in Europe, after a period in a major urban center, all three ended up “rural” to a degree in America as well, something that appears to have been another variable shaping their social and personal identities.

Like many immigrants of that period, their personal and cultural identities were molded to a certain degree by the American economic and cultural values which they encountered, but their responses to the “culture shocks” they underwent differed somewhat. Rabbi Samuel Gordon remained devout and was the practicing Rabbi and ritual slaughterer of the Tarrytown Jewish community, but had to earn his actual living as a house painter. Hyman Schwartz, the seventeenth generation of rabbis according to family lore, left the rabbinic world soon after reaching America, and like his brother Joseph who preceded him, ended up in a profession that enabled him to remain “traditional” but no longer Orthodox or “devout”. This was a common transition which many Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe underwent during the “Great Wave of Immigration” to the United States (1881–1914).

All of them left behind their familiar social and family support, but soon found alternative support systems and slowly became part of various American frameworks, both communal and professional. Rabbi Samuel Gordon was the Rabbi and religious functionary of the Tarrytown Jewish community. Hyman Schwartz became a central figure in the Nyack Jewish community and a well-respected storekeeper. Joseph Schwartz found his niche in the garment industry, but we know little about his communal framework, possibly because of his death at a young age.

Similar to many in the “Great Wave of Immigration”, their economic status indeed changed, first to the worse and later to the better, in comparison with their life in Europe. As for discrimination and intolerance, while it certainly existed in the American society of their time, their lives in America were by far better in this respect than they had been in Europe.

Discovering more about family chronology, personal transitions, and choices of profession and location—frameworks for understanding the “we”—was equally illuminating in terms of reaching a better understanding of later family dynamics affecting the “me”. One in particular was the social and cultural family contexts into which present-day family members, such as my husband and his siblings, were born. By unearthing stories that provided a better understanding of family lore, they could better grasp the broader context of childhood memories, such as visiting family on a poultry farm in New Jersey, or explanations of where certain family names came from.

Maybe the most significant aspect of a genealogical family journey is the way that fragments of the past help one (re)conceptualize the present. By having a better understanding of one’s ancestors, their descendants may gain insight into various components of their own “self”, their cultural identity, and even the choices to which they may “naturally” gravitate that in truth may be weighted in family history or experiences. “Unearthing the ‘Polonskis’” is therefore not just a study in migration and a discourse on family lineage, but provides hints to the transformation of a family, at least its American branch. Combining explanations from topics ranging from language and gender to timing and awareness, it offers an explanation as to why various incidents in a family history are forgotten while others become beacons for future generations. Reconstructing a family genealogy may not provide the answers to all of one’s queries regarding one’s ancestors, but it hopefully teaches us what questions to ask in the present, in order to lay the basis for the responses to similar questions about ourselves that will ultimately be asked by future generations.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Baumel, Judith Tydor. 1998. Double Jeopardy: Gender and the Holocaust. London: Vallentine Mitchell. [Google Scholar]

- Baumel-Schwartz, Judith Tydor. 2017. A Very Special Life: The Bernice Chronicles. One Woman’s Journey through Twentieth Century Jewish America. Bern: Peter Lang. [Google Scholar]

- Bogdanova, Rita, Menachem Barkahan, and Natan Barkan. 2004. Latvia: Synagogues and Rabbis 1918–1940. Riga: Shamir, p. 238. [Google Scholar]

- Cerulo, Karen A. 1997. Identity Construction: New Issues, New Directions. Annual Review of Sociology 23: 385–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chodorow, Nancy. 1978. The Reproduction of Mothering. Berkeley: University of California Press, p. 150. [Google Scholar]

- Fearon, James D. 1999. What is Identity? (As We Now Use the Word). California, Stanford University. Available online: https://web.stanford.edu/group/fearon-research/cgi-bin/wordpress/wp-content/uploads/2013/10/What-is-Identity-as-we-now-use-the-word-.pdf (accessed on 14 November 2017).

- Feigmanis, Aleksandrs. 2006. Latvian Jewish Intelligentsia Victims of the Holocaust. Riga: Author’s publishing, Available online: http://www.jewishgen.org/latvia/LatvianIntelligentsia.html (accessed on 12 April 2017).

- Foley, John Miles. 1988. The Theory of Oral Composition: History and Methodology. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fowler, Glen. 1988. Harry H. Gordon, 81, A Pioneer in Baby Care, Child Development. The New York Times. July 22. Available online: http://www.nytimes.com/1988/07/22/obituaries/harry-h-gordon-81-a-pioneer-in-baby-care-child-development.html (accessed on 19 December 2017).

- Froncek, Thomas, ed. 1991. From Generation to Generation: A Centennial History of Congregation Sons of Israel 1891–1991. Upper Nyack: Congregation Sons of Israel. [Google Scholar]

- Grinberg, Leon, and Rebeca Grinberg. 1989. Psychoanalytic Perspectives on Migration and Exile. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, pp. 130–32. [Google Scholar]

- Henige, David. 1982. Oral Historiography. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Hitlin, Steven. 2003. Values as the Core of Personal Identity: Drawing Links between Two Theories of Self. Social Psychology Quarterly 66: 118–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hofstetter, Eleanore O. 2001. Women in Global Migration 1945–2000. Westport: Greenwood. [Google Scholar]

- Inskeep, Carolee R. 2000. The Graveyard Shift: A Family Historian’s Guide to New York City Cemeteries. Orem: Ancestry. [Google Scholar]

- Khinutz, Nakhum. 1970. The Lida Yeshiva. In Sefer Lida. Edited by Alexander Manor, Itzchak Ganusovitch and Aba Lando. Tel-Aviv: Former Residents of Lida in Israel and the Committee of Lida Jews in the USA, pp. 131–33. Available online: http://www.jewishgen.org/yizkor/lida/lid131.html (accessed on 12 April 2017).

- Knauft, Bruce. 2017. What Is Genealogy? An Anthropological/Philosophical Reconsideration. Genealogy 1: 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretsedemas, Philip. 2017a. Genealogy: Inaugural Editorial. Genealogy 1: 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kretsedemas, Philip. 2017b. What Is Genealogy? Introduction to the Inaugural Issue of Genealogy. Genealogy 1: 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewin, Issac. 1972. Eleh Ezkera [These I Will Remember: Biographies of Leaders of Religious Jewry in Europe Who Perished during the Years 1939–1945] (Heb.). New York: Research Institute of Religious Jewry, pp. 137–40. [Google Scholar]

- Lindell, Joseph. 2009. Beacon of Renewal: The Educational Philosophy of the Lida Yeshiva in the Context of Rabbi Isaac Jacob Reines’ Approach to Zionism. Modern Judaism 29: 268–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazey, Mary Ellen, and David R. Lee, eds. 1983. Her Space, Her Place: A Geography of Women. Washington: Association of American Geographers. [Google Scholar]

- Nann, Beverly. 1982. Settlement Programs for Immigrant Women and Families. In Uprooting and Surviving: Adaptation and Resettlement of Migrant Families and Children. Edited by Richard C. Nann. Dordrech and Boston: D. Reidel Publishing Company, p. 87. [Google Scholar]

- Oliver-Smith, Anthony. 1982. Involuntary Migration and Resettlement: The Problems and Responses of Dislocated People. Boulder: Westview Press. [Google Scholar]

- Paull, Jeffrey Mark, and Jeffrey Briskman. 2015. The Jewish Surname Process in the Russian Empire and its Affect on Jewish Genealogy. Avotaynu Online Jewish Genealogy and Family History, October 6. [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, Ira. 1907. Rabbis and Their Community: Studies in the Orthodox Eastern European Rabbinate in Montreal, 1896–1930. Calgary: University of Calgary Press, pp. 81–82. [Google Scholar]

- Soyer, Daniel. 2002. Jewish Immigrant Associations and American Identity in New York 1880–1939. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stampfer, Shaul. 2012. Lithuanian Yeshivas of the Nineteenth Century: Creating a Tradition of Learning. Oxford and Portland: The Littman Library of Jewish Civilization. [Google Scholar]

- Svirsky, Nachke. 1956. The Annihilation of Dunilovici. In Hurbn Glebokie, Szarkowszczyzna, Dunilowicze, Postawy, Druja, Kaziany: Das Leben un Unkum Fun Yiddishe Shtetlach in Veisrusland-Lita (Vilner Gegant). Edited by Shlomo Suskevitch. Buenos Aires: Lansleit freiern fun Szarkowszczyzna, Dunilowicze, Postawy, Druja, Glebokie un umgegnet in Argentina. [Google Scholar]

- Vertovec, Steven, ed. 1999. Migration and Social Cohesion. Cheltenham: E. Elgar Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Weiss, Rabbi Moshe. 1965. Rabbi Isaac Jacob Reines: Founder of Mizrachi, the World Religious Zionist Organization. New York: Mizrachi Hapoel Hamizrachi, Available online: http://israel613.com/books/ERETZ_RABBI_REINES.CV.pdf (accessed on 12 April 2017).

- Williams, Bernard. 2004. Truth and Truthfulness: An Essay in Genealogy. Princeton: Princeton University Press, p. 20. [Google Scholar]

- Yow, Valery Raleigh. 1994. Recording Oral History: A Practical Guide for Social Scientists. Thousand Oaks: Sage. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The original 1804 decree by Czar Alexander I required all Jews in the Russian Pales of Settlement to adopt permanent surnames. This was strengthened by an 1835 edict of Czar Nicholas I declaring that the chosen surnames could not be changed. See (Paull and Briskman 2015). |

| 2 | Regarding the need for caution with oral documentation see (Foley 1988; Henige 1982; Yow 1994). |

| 3 | New York State Census. 1905. Database with Images. FamilySearch. Available online: https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MV1W-MMX (accessed on 19 December 2017), Samuel Gordon, Mount Pleasant, North Tarrytown Village, E.D. 01, Westchester, New York; citing p. 36, l. 24, county offices, New York; FHL microfilm 589,697. |

| 4 | United States Census. 1910. Database with Images. FamilySearch. Available online: https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:M57G-MFT (accessed on 13 March 2017). Samuel Gorden, Tarrytown, Westchester, New York, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 32, sheet 8B, family 15, NARA microfilm publication T624 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1982), roll 1089; FHL microfilm 1,375,103. United States Census. 1920. Database with Images. FamilySearch. Available online: https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:MV37-KHX (accessed on 2 February 2018), Samuel Gordon, Greenburgh, Westchester, New York, United States; citing ED 31, sheet 2B, l. 56, family 43, NARA microfilm publication T625 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 1992), roll 1276; FHL microfilm 1,821,276. United States Census. 1930. Database with Images. FamilySearch. Available online: https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:X4GW-BYH (accessed on 2 February 2018), Samuel Gordon, Tarrytown, Westchester, New York, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 147, sheet 25A, l. 36, family 487, NARA microfilm publication T626 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2002), roll 1660; FHL microfilm 2,341,394. |

| 5 | United States Census. 1930. Database with Images. FamilySearch. Available online: https://familysearch.org/ark:/61903/1:1:X4K3-Q37 (accessed on 4 February 2018), Esther Peters in household of Abraham Peters, Brooklyn (Districts 0501-0750), Kings, New York, United States; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 574, sheet 15A, l. 11, family 292, NARA microfilm publication T626 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, 2002), roll 1543; FHL microfilm 2,341,278. |

| 6 | The Tarrytown Daily News, Monday, 11 September 1933, front page. |

| 7 | Tarrytown death records, 56,709, 11 September 1933. |