1. Introduction

Among the several medieval Beauchamp families, the patrilinear lineage associated with Warwick and Bedford is comparatively well documented, partly because members of several branches were included in the parliamentary baronage. The amount of documentation available makes it possible to chart how individual members of this lineage choose, or were assigned, individual brisures, and evaluate the validity of the attributions and the quality of the evidence. This can only be an example, not a general statement on the armorial practice of the period of 1250–1500. The object of this article is to survey the armorial practices of the branches of the Beauchamp lineages related to the earls of Warwick, not to revise the genealogy. The pedigrees referred to are those in the standard literature—mainly the multi-volume publication of

The Complete Peerage initiated by George Cockayne, Clarenceux king of arms, and written largely by Vicary Gibbs (GEC).

1 For the Beauchamps, as for many other lineages, it is largely a revision of the baronial genealogies prepared by the antiquarian William Dugdale (

Dugdale 1675), but with additional documentation. There is an easy survey of the pedigree by Dugdale in a history of Northamptonshire (

Baker [1822] 1836, pp. 218–19), and further notes on the Beauchamps of Warwick and their papers in the study by K.B. McFarlane (

McFarlane [1973] 1997, pp. 187–201). Unless noted otherwise, GEC is the source used here for descendence and relations between branches. There are numerous genealogical websites, which mention the Beauchamps and present coats of arms assigned to individuals. These are of very variable quality and trustworthiness, and should be used with extreme care. A few cite pertinent documentation, usually calendared governmental documents, e.g., Inquisitions Post-Mortem. The present paper only touches the lineage where relevant for the discussion of arms, or to suggest candidates for inclusion into the lineage.

While seals are standard references in genealogical and historical research, especially from printed collections of descriptions of seals (those consulted are in the bibliography), armorials a.k.a. rolls of arms, are a largely untapped as source material. Accessibility is one of the practical reasons, as the manuscripts are widely spread. Fortunately, most medieval armorials compiled in England and/or on the Continent with segments of English arms have been catalogued and annotated, the former by Anthony Wagner (

Wagner 1950,

1967), and the latter by Michel Popoff (

Popoff 2003) and by Steen Clemmensen (

Clemmensen [2006] 2017).

All of the armorials (and all manuscript versions) compiled during the reign of Edward I have been edited and published (

Brault 1997). Those transcribed before 1967 are listed in the catalogues, and a few modern editions and transcriptions of other armorials have been published (e.g., by Tremlett and London in (

Wagner 1967;

Boos 2004;

Clemmensen 2006b,

2007,

2009a,

2009b,

2016a)) and entries in several more are available mainly in the Dictionary of British Arms (DBA)

2 or from (

Clemmensen [2006] 2017). For genealogists interested in medieval families there is now easy access to both seals and armorials as supplements to chronicles and calendared materials, but one ought to be aware of the types of armorials, pitfalls and variable quality of these sources (

Wagner 1950;

Clemmensen 2012,

2016b,

2017a). Fortunately, there is little evidence of extensive copying between the earlier English armorials—as opposite to variant manuscript versions, of which there are many thanks to the efforts of members and associates of the College of Arms. Many of the later English armorials (from Edward III on) have not been sufficiently analyzed as to the dating of their compilation and the extent and origin of possible older material. Dating the contents is a crucial question when using ordinaries, armorials structured according to the principal charges on the arms. These include Cooke’s Ordinary, Thomas Jenyns’ Book, and William Jenyns’ Ordinary, which are largely derived from earlier sources. It is evident from the primary manuscript of the Parliamentary Roll that some names and blazons were added later, but these are rarely identified in the available transcriptions. Most Tudor armorials incorporate a substantial amount of older material.

The theory and general armorial practice of marking cadency have had several treatments in recent years. Emblematic representation according to an individual’s place in the lineage was recently discussed by D’Arcy Boulton (

Boulton 2005,

2012). Both Cecil

Humphery-Smith (

1988, p. 100) and Paul

Fox (

2008) have commented on theory and practice and given examples of the most common choices made—mostly from studies of armorials. The majority preferred a label, chief, border or bend (often classified as ordinaries), changing the tinctures of field or primary charges, or placing charges around ordinaries (one or more in combination).

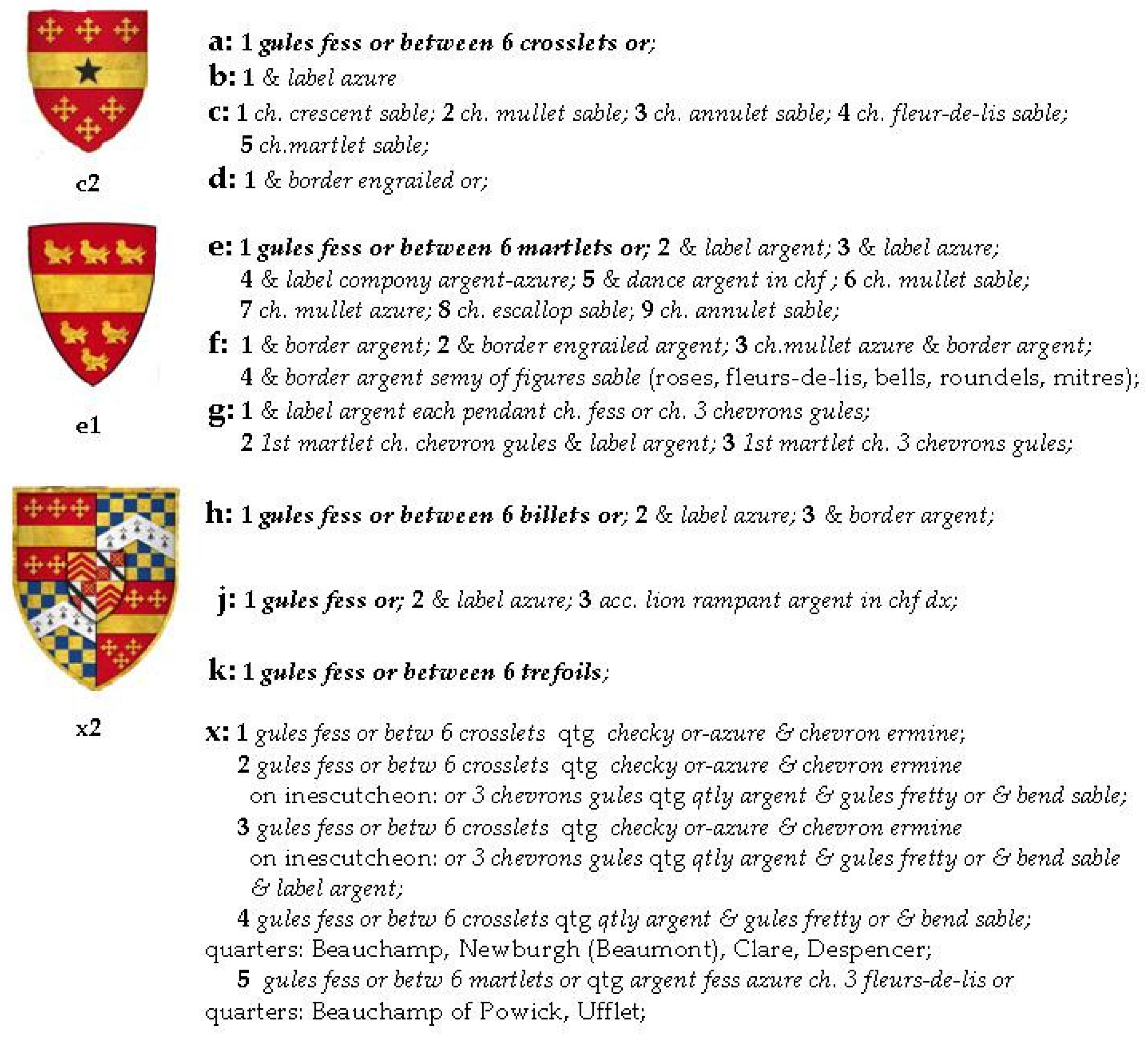

Several of the coats of arms used by the Beauchamps have been described and documented individually, mostly in the identification of seals, but also in the abovementioned transcriptions and editions of armorials, see

Figure 1. However, there has been only one attempt to survey the overall use of differences (

Wagner 1958). This was made in the context of a semi-popular presentation without any documentation and without critical analysis of eventual reuse of arms or mis-assignments. It was not stated, but Wagner did use the vast collection of armorials in the College of Arms and the research libraries of England. The present paper aims to bring his survey up to date, document the use arms and suggest a few previously unnoted members. For these 44 seals and 151 entries in 74 medieval armorials were reviewed.

3 More entries in Tudor and later armorials are available through the DBA, but post-1500 descriptions should be considered to be of little value as evidence as are images in Tudor illustrated manuscript pedigrees (e.g., Warwick-Essex). These were made after the lineage became extinct.

3. Warwick Branch

The senior branch of Warwick (

Figure 1) descended from William (IV, d. 1298), eldest son of William (III, d. 1268) and Isabel Mauduit, who at the same time inherited his father and had enough influence with Henry III and the Lord Edward to ‘inherit’ the earldom of Warwick from his maternal uncle. From the point of armoury this branch is so predictable to be almost boring (DBA 3: pp. 303, 445, 492, 510). Of interest for students of art history and military costume, there are two effigies and a brass plate for three generations of earls of Warwick in St. Mary’s Church, Warwick (

Scholes 1963). The eldest son bore the basic arms on succession (

Gules a fess or between 6 crosslets or;

a1) and before that a

label in chief (

b1). The label was and is generally used by the eldest son, though with changes of tincture or the addition of charges, it may be extended to other sons and even be used as hereditary brisure in a cadet line. The only documentation of the use of a label by this branch is Guy (II, d.1351), who died before his father, but it is most likely that the label was used by all first sons in the senior branch.

The ‘usual’ brisure for brothers in this branch was the addition of a smallish additional charge on the fess, apparently in the order: Annulet (c3), fleur-de-lis (c4), crescent (c1), and mullet (c2), which is different from the order codified by the Tudor theorists after 1500 and found in most textbooks today. However, making a general conclusion for just the one and only generation with many sons will be an over-interpretation. When Thomas (III, d. 1401), the second son, was old enough to need a personal brisure, his uncle John (IV, d. 1360) was still living, so the mullet was already used. It had to wait until the uncle died before the fifth son, John (VI), could reuse it.

Both Johns appear in English and French armorials, and that is the only real evidence available for their use of brisure. No seals belonging to them were found. The elder John (IV) was a notable soldier and as a founder-knight of the Garter must have been known to his opponents, and the entry as John in Powell 385 is spot on. He is also noted in the French (Navarre 1473) (as John) and Urfé 167 (as sire) with identical written blazons. So far so good, but there is a hitch. Both armorials are conventionally dated to c.1380, almost a generation after his death (

Popoff 2003, p. 271, no. 2199, p. 286, no. 2272), and are generally regarded as being compilations of contemporaries. One way of solving such contradictions is to assume that the armorials did incorporate older material—and they did (

Clemmensen 2017a, pp. 133–49, 203–13). The younger John (VI) could well be living up to 1390, which would be commensurate with inclusion in Willement 9 and William Jenyns 561.

Different sources may provide contradictory results. Paul Fox noted that shortly before they were destroyed during the Civil War of the 1640’s, Wencelaus Hollar copied a set of stained glass windows in the Beauchamp Chapel in St. Mary’s, Warwick (

Fox 2008, p. 24). These depicted the arms of the six sons of Thomas (II, d. 1369, 3E) with slightly different brisures from those presented in

Figure 2. The 3rd son (Reynbrun) had a crescent (

c1), and 4th son (William) his fleur-de-lis (

c4). John (VII) has the mullet (

c2) as 5th son, as in

Figure 2, and Roger (II) was given the martletÿ (

c5), which is otherwise only known for a late attribution to a William. In this case it was probably the glazier, who made the mistake, as the seals of William (VI) of Abergavenny have the crescent (Birch 7274, a.o., DBA 3, p. 492)—unless the reader prefers Dugdale to be wrong on the sequence of sons.

After the accession of Thomas (II) in 1329 (GEC 12B, p. 372) the earls also used composite arms with quarters representing the senior branch (basic arms of the family) and quarters representing the earldom and presumptive inheritances, i.e., marriages with heiresses (real or potential). The earliest version (

x1) quartered Beauchamp with ‘Newburgh’ a.k.a. ‘le veyl escu de warrewic’ as recorded in Antiquaries 4 from 1352/60. The latter arms,

Checky or and azure, a chevron ermine, refers to the extinct first earls of Warwick of the Beaumont lineage, who held the title from 1088–1242, and was adopted by Guy (I) and placed on his counterseal in 1301 (Birch 5658). The Beaumonts were famous, having held several earldoms in England, as well as counties in France, and may have been descended from Charlemagne himself (

Crouch 1986;

Clemmensen 2016b, p. 71).

Richard (II, d. 1439, 5E) added two more coats of arms quartered on an inescutcheon (Birch 7253, Egerton 33, x2) after his marriage in 1423 to Isabel Despencer, daughter of Thomas E.Gloucester and widow of his cousin Richard (III, d. 1422) E.Worcester. They were Clare (Or 3 chevrons gules) and Despencer (Quarterly fretty argent-gules-or and a bend sable over all) for his wife and her father’s earldom (Birch 7253; Egerton 33). Their son, Henry (d. 1446, 6E), the last of this line, used the same arms with a label over all (x3). Henry’s daughter Anne married Richard ‘the Kingmaker’ Neville (d. 1471), who also ‘inherited’ the earldom. Richard (II, 5E) was probably the most renowned of the Beauchamp earls and his exploits as a jouster, soldier and diplomat was recorded in the Beauchamp Pageant. The composite coat (Beauchamp qtg Despencer, x4) noted in Peter le Neve 111 for ‘lord bughgeny’, must be for Richard (III, d. 1422) of Abergavenny, E. Worcester 1421, who was the first husband of Isabel Despencer. The Gloucester title, which had earlier been granted to husbands of heiresses to Clare, was occupied by Humphrey of Lancaster (d. 1446), a younger brother of Henry V.

There was no evidence of the use of arms for four members of this branch among the sources examined. There may be entries in late Tudor (Elizabethan) and Stewart armorials, but as they are at least second, if not third or later, hand, they ought to be treated with outmost circumspection. For practical reasons descriptions of seals can be treated as primary evidence—with the proviso that one may with reason doubt their accuracy.

One coat of arms in a late armorial for a William (Basynge’s Book 74, c. 1395, DBA 3, p. 494, c5), where the

fess is charged with a ÿ escenda, has probably got the name wrong. William (VI, d. 1411) of Abergavenny, the only relevant person who used a crescent on his seal. However, the text of Birch 7277 of a seal of a William of 1432 mentions a crest and a ÿescenda on the field, but not whether this is on a shield of (unspecified) arms. The last coat of arms (

d1, border engrailed) in second DunsTable 98 for a John in a 1334 tournament ought to fit John (IV, d. 1360), at the age of 18. But John (IV) has a mullet for difference in Powell 385 and Navarre 1473. He may have changed arms during his career beginning with a more prominent difference, and later assimilated his brisure to those of his nephews (or brother). That would have been the conclusion, if the difference had been a plain border. But a border engrailed may indicate one more step off the parent line, i.e., a third or later son. John (IV) was a second son. The

d1 (crucily and border engrailed) can be interpreted in three ways: For an unplaced John (XIII), as a fictitious attribution, or as an unusual choice by John (IV). All recorded male members of this line are in

Figure 2.

Anthony Wagner kept his Warwick branch a little shorter, ending it with the three brothers Guy (II, d. 1351), Thomas (III, d. 1401, 4E), and William (VI, d. 1411) of Abergavenny. There are only two differences among the men present in both pedigrees: Firstly, that William may have used, or been attributed,

a ÿ escenda sable (

c5, as above), and more surprising that Guy (II), the eldest son of Thomas (II, 3E), should have used the arms of the Powick line with a

border engrailed (

Wagner 1958, no. 9,

f2).

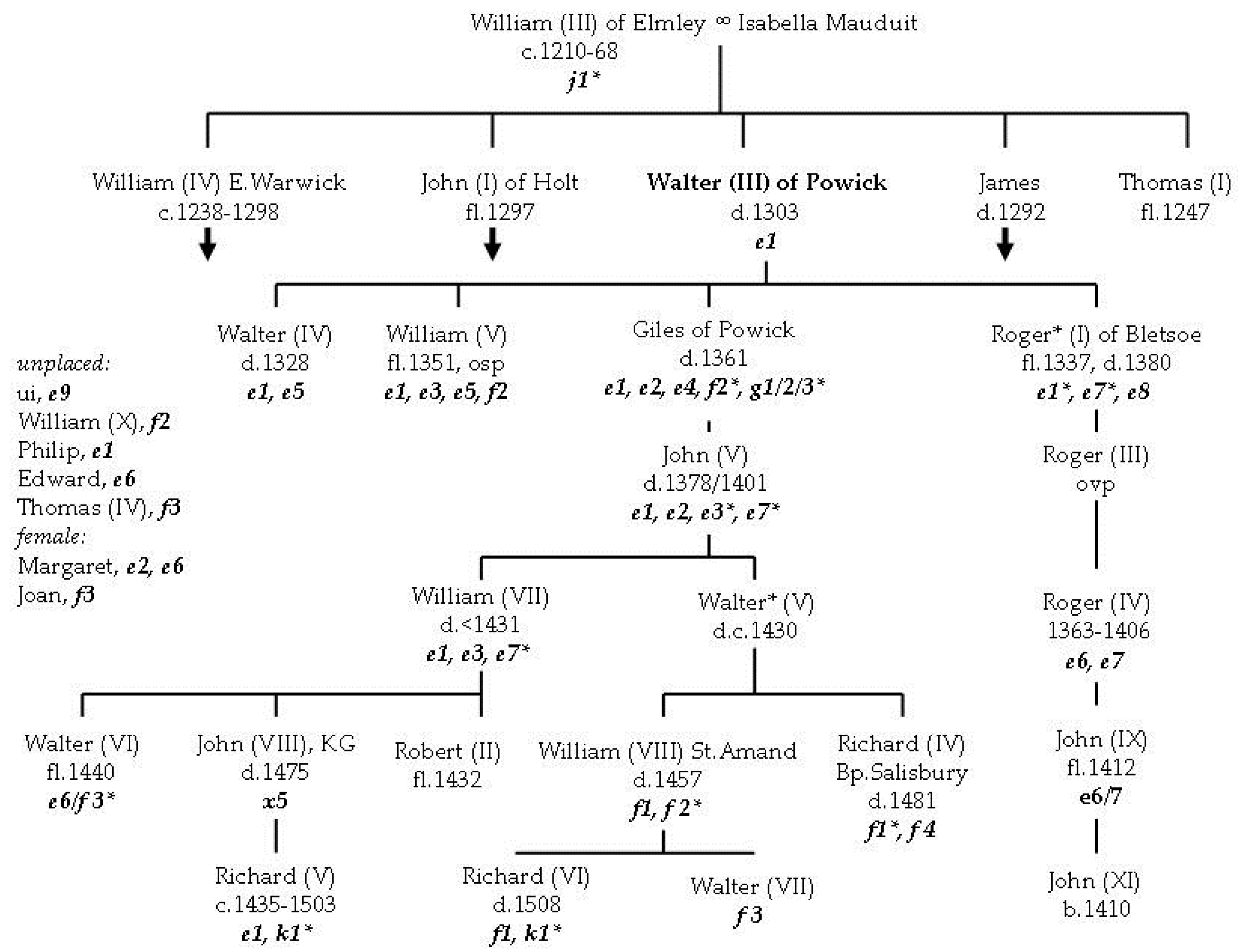

4. Powick and Bletsoe Branches

The founder of the Powick sub-branch substituted the cross-crosslets with martlets to make the basic arms

Gules fess or between 6 martlets or (

e1, DBA 3, pp. 375–78). These arms are attested both on seals and armorials. As noted in

Figure 3, it split off two sub-branches of its own: First Bletsoe, then St. Amand. This line also contains most of the problems in the pedigree, in the individual’s use of multiple arms, and in differences with Wagner.

The pedigree is unsatisfactory and need further research. The Complete Peerage has most of the sub-branch as footnotes, because it only reached baronial status in 1446 with John (VIII, d. 1475) and in 1449 with his cousin William (VIII, d. 1457), who married Elizabeth Braybroke, heiress to the St. Amand ‘title’. The Bletsoe (Worcs.) baronial title came comparatively early—in 1363, but was only transitional. The parentage of its founder Roger (I, d. 1380) and his baronial status will be reviewed in the main discussion at the end. For the present, the conclusion that Roger was a younger son of Walter (III, d. 1303) will be retained here.

The basic or chiefly arms of the Powick sub-branch, adopted after 1250, followed the eldest surviving son of the Powick (Worcs.) branch on succeeding. This branch was also known for its manor of Alcester (Warws.). The attribution of the basic arms to Roger (I) of Bletsoe (PRO-sls, Roger 1379/80, DBA 3, p. 375) is likely due to a misreading of the wax image, unless he deliberately omitted his brisure on his seal, of which no other description was found. The PRO seal noted as from 1357/58 in the DBA for Walter of Alcester must be misdated. It does not fit either Walter (IV, d. 1328) noted as a baron of Alcester 1306 or Walter (V, d.c. 1430).

4.1. Beauchamp of Bletsoe

It is easiest to dispose of the Bletsoe sub-branch first. The mullet brisure (e6, e7, DBA 3, p. 488) became hereditary in this branch. It is found both as azure (blue) and sable (black). These tinctures are so close as to be difficult to distinguish and as many dark blues fade to black with age, the two apparent variants should be considered to represent the same coat of arms, though one could argue that the azure mullet was used by the Powick branch and only mistakenly applied to a Roger in William Jenyns 569. This is unlikely, however, as the two mullets would have been too easily confused for them to be effective as differences.

There are five problematic occurrences of the mullet as recorded in DBA 3:488. The first is for an unplaced Edward (William Jenyns 572,

e6) of an unknown period. The William Jenyns armorial does incorporate older material (

Clemmensen 2017a, pp. 276–80), and lists 15 Beauchamps between nos. 553–572 on fo.19r with active periods between 1325 and 1400. The second, Picquigny 43 (

e7) is probably for William (VII, d. < 1431) of the Powick branch, but this French armorial is hard to date. It contains only English arms, of which many are also found in armorials of the Toison d’or group of armorials, and it has only survived in a late copy by Charles du Cange (

Clemmensen 2017a, pp. 122–23).

The third occurrence of a mullet is the one attributed to the three entries of a Roger in William Jenyns 569 (e7), Willement 550 (e6), and Basynge 217 (e6). All three are most likely for Roger (IV, 1363–1406) with the mullet of different tinctures. His daughter Katherine (d.1436) and her husband Thomas Torrel (d.1442) have left a brass at Willingale Doe (Essex). Her arms have the mullet as difference. The 1447 seal of Margaret, wife of John Beaufort D. Somerset, sister and heir of John (XI) of Bletsoe (Birch 7286) can be cited as a support for the hereditary use as it includes the mullet. Her children with her first husband Oliver St. John added ‘of Bletsoe’ to their name, and her daughter Elizabeth St. John and her husband William Zouche (d. 1462) left the mullet brisure on their brass in Okeover (Staffs.).

The fourth is related to the third as it concerns the ancestor Roger (I, d. 1380). If the mullet was the only brisure used by this branch, one would expect that the ancestor would have it too. If the entry of Bletsoe (mullet) impaling Pateshull in the Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries 17, p. 56 can be trusted, he did. Roger (I) married Sibyl Pateshull (d. > 1351) as his first wife. However, his contemporary John (V, d. 1378/1401) of Powick, probably a nephew, married Elizabeth Pateshull, and their son William (VII, d. < 1431) and grandson Walter (VI, fl. 1440) probably also used a mullet for difference. Walther (VI) of Powick, as a fifth problem, will be discussed below as the major difficulty is the presence or absence of a border.

If Roger (I) did not use the mullet, he may have used an escallop and be the Roger in Navarre 1475 (e8). It would fit the sequence Navarre 1473 for John (IV, d. 1360, KG) of the Warwick branch, Navarre 1474 for John (V, d. 1378/1401) of the Powick branch. There are no arms available for Roger (III, o.v.p.) or John (XI), who died young and unmarried. They may have used the mullet, especially Roger (III) while active together with his father Roger (I). The use of a mullet by John (IX, fl. 1412) is a safe conclusion as both his daughter and granddaughter remembered it so.

The only Bletsoes mentioned by Anthony Wagner are (1) Roger (I) with

Gules a fess or ch. Mullet sable between 6 martlets or the whole within a border argent, probably from a Tudor armorial (

Wagner 1958, no.18; DBA 3, p. 512,

f3), and (2) his son Roger (III, o.v.p.) for whom we have no arms). The border was present in the drawing, but omitted in his blazon.

4.2. Beauchamp of Powick or Alcester

The basic arms of the Powick or Alcester branch were

Gules a fess or between 6 martlets or (

c1) chosen by Walter (III, d. 1303) of Alcester and noted in 11 armorials from the reign of Edward I (

Brault 1997, vol. 2, p. 41). As expected, they were used sequentially by the eldest son as he succeeded. A series of seals confirms this (DBA 3, pp. 375–78, Birch 7246 a.o.) The most impressing example is the magnificent tomb-chest and effigy of John (V, d. 1378/1401) and his wife Elisabeth Pateshull (d. 1411) in Worcester Cathedral (

Downing 2002, pp. 175–77; Worcester Cathedral website). She is dressed in plain finery and he in full plate armour with an armorial jupon of the basic arms edged blue—not a

border engrailed azure. The tomb-chest has five shields on each side: In the centre the Warwick arms, representing this glorious lineage, between the Powick arms for the branch he was heading, and on the outside Powick impaling Pateshull for the married couple. The Pateshull arms have been changed slightly when the painting was refreshed. It now has the

fess azure rather than the

Argent fess sable between 3 crescents gules uniformly found in armorials.

Arms are known for nearly all of the six generations of the Powick branch. The sub-branch of St. Amand descended from Walter (V, d.c. 1430) is discussed below. Both Wagner and

Figure 3 have a multitude of differences for the sons and one grandson of Walter (III) of Alcester, as he is usually known. He had four known sons, two of whom apparently died without issue, leaving the third Giles of Powick to propagate the line. The fourth brother was Roger (I) of Bletsoe as noted above. The eldest son Walter (IV, d. 1328) fought together with his father in the Galloway campaign of 1300 bearing a

dance (a bar dancetty in chief, i.e., a narrow zick-zack band above the fess) for difference (Galloway 47). On succeeding, he removed the difference, which was then adopted by the next-born brother William (V, fl. 1351) and kept for some years after he succeeded, at least until 1334 (2nd DunsTable 111). William is known to have dropped the

dance before he died, possibly before 1340 (Cooke’s Ordinary 366; Antiquaries 281). Before that, around 1308–14, he, or a namesake, appears to have used

border engrailed argent as difference (Harleian 43, a poem; 1st DunsTable 90, Parliamentary 879), but see below in the general discussion of the border difference.

The third brother, Giles (d. 1361), has been assigned no less than seven coats of arms in the armorials, including differences of a label argent, a label compony argent-azure, border engrailed, and variations of the Clare arms of Or 3 chevrons gules. The border (f2) and Clare differences (g1–3) will be analysed in detail in the discussion at the end of the paper. Wagner made similar assignments to the three brothers. That Giles would use the basic Powick arms comes as no surprise, and is substantiated by his seal (DBA 3, p. 377, BirmCL-sls I, 168421). The interesting point is when did he shed the differences. Taken at face value, it must have been no later than 1348 (Powell 387), when his elder brother was also using the basic arms. The contradiction may be resolved in various ways. One possibility is that the two entries mentioned above for William (V) were unfinished, and he kept his difference as he had no heirs of his blood coming, and so let his younger brother have armorial priority. That John (V), son of Giles, bore a label for difference (e2) in Powell 394, supports this interpretation. Both Giles in 1338 (DBA 3, p. 443; Oxford, Bodley, Dugdale 17, p. 2) and John (DBA 3, p. 444, BirmCL-sls I, 168241) had seals with a label. That Giles is also attributed a label compony in 1348 (Styward 10) is a minor problem. He may have discharged his arms of the brisure that year if he was knighted after the siege of Calais.

John (V, d. 1378/1401) was noted above with basic arms on his effigy and label argent on seal and in an armorial. The label azure in William Jenyns 571 may well be a mistake by this later copyist. What is more intriguing is the possible change from label to a mullet on the fess (e6, e7, f3) noted for John (V), his eldest son William (VII, d. < 1431), and grandson Walter (VI, fl.1440) in French armorials (Picquigny 43, Navarre 1474). A change probably made around 1360 if Navarre is taken as an indication. A Walter son of William has conflicting descriptions of his brass in Checkendon in Oxfordshire (DBA 3, pp. 448, 512), which will covered in the main discussion on borders.

Finally, Wagner has the basic arms for John (VIII, d. 1475, KG 1446), probably from Tudor armorials, but not his Beauchamp of Powick quartering the maternal Ufflet in Writhe’s Garter Book 182 (x5). The use of a fourth primary difference: Gules fess or between 6 trefoils or by a Richard around 1450 (Creswick 1570) will be dealt with in the discussion.

4.3. Beauchamp of St. Amand

The St. Amand sub-branch of Beauchamp of Powick had only four members. The founder, Walter (V, d.c. 1430), has left no arms. His eldest son William (VIII, d. 1457) who was summoned to Parliament as a baron in 1449 bore the basic Powick arms according to Wagner, probably from Tudor material, though the present examination suggests that he bore as a difference either the

border plain argent (DBA 3, p. 451,

f1), or a

border engrailed argent (Red Book, p. 84,

f2). The younger son, Richard (IV, d. 1481) became Bp.Salisbury, and has also been recorded as having impaled the

border argent with the arms of the diocese (College of arms, M3, no. 811). This book is a kind of miscellany, known as Ballard’s Book. It has a major part written by William Ballard March king of arms (d. 1490), but also have parts written and painted by Thomas Wriothesley Garter king of arms (d. 1534), who was an extremely productive compiler of armorials from older material. It was not possible to examine this manuscript and the catalogue by (

Campbell and Steer 1988, pp. 97–102) does not allow any form conclusion as to the authorship, but the entry number 811 given by the transcriber F.N. Davis (d. 1954) suggest a place in the latter part of the book. Other sources (DBA 3, p. 452,

f4), also noted by Wagner, has the

border semy of small figures, which have been rendered as anything from roses, fleurs-de-lis, bells, and roundels to bishop’s mitres. The last member of this sub-branch, Richard (VI, d. 1508), son of William (VIII), also has the

border argent (DBA 3, p. 451,

f1) in Tudor armorials, which were largely made in the Wriothesley studio.

Wagner’s pedigree has a Walter (d.c. 1430) with Gules a fess or ch. Mullet azure between 6 martlets or within a border argent (f3), which overlaps the Checkendon brass explained in the main discussion.

5. Two Junior Branches

According to Dugdale, as cited by Baker (

Baker [1822] 1836, p. 220), William (III, d. 1268) and Isabella Mauduit had five sons, of whom the descendants of William (IV) of Warwick and Walter (III) of Powick has been discussed above. Thomas (I, fl. 1247) probably died unmarried, and the ÿescendance of James (d. 1292) is so sketchy as to be almost hypothetical. It is noted here simply as the ‘junior line’. The single-stranded Holt branch founded by John (I, fl. 1297) has been reconstructed, primarily due to the low probability of John (X) fathering at the age of sixty, and at the same time being a favourite of the twelve year old Richard II, godfather of his son John (XII).

5.1. Beauchamp of Holt

John (I, fl. 1297) Beauchamp of Holt (Worcs.) was very active in the wars of Edward I, noted 1275 in Dering 254, and left his arms

Gules a fess or between 6 billets or (

h1) in several of the period armorials (

Brault 1997, vol. 2, p. 40). The arms are also found in the seals of his descendent John (X, d. 1388), e.g., Ellis 52 (DBA 3, pp. 301–2). The standard pedigree has four generations: John (I, fl. 1297)—Richard (I, d. 1327)—John (X, c. 1319–88)—John (XII, pp. 1378–420). If the armorial evidence can be trusted, it needs to be expanded to the six generations listed in

Figure 4. However, one should bear in mind that both compilers and modern writers may confuse names. Anthony Wagner replaces John (X, d. 1388) of Kidderminster with a Richard (

Wagner 1958, p. 365).

There is apparently no evidence for the arms of Richard (I, d. 1327), who may have been unfit for military service already in the early 1310’s. John (I) may have lived until c.1314, when a John has the basic Holt arms in Parliamentary Roll 449 (from Essex), and while his presumed son John (III) bears a label argent (h2) in Harleian 65 from 1314. John (VII) was about eight years when Richard (I) died, and is proposed to be the Jenkyn mentioned in William Jenyns 567. The son of Richard can hardly be John (X, d.1388), Lord Beauchamp of Kidderminster 1387, who would be sixty, when King Richard II became godfather of his son John (XII, pp. 1378–420). With only some forty years between the first warlike appearance of John (I) and the birth of John (VII), one may exclude John (III) from the pedigree and claim John mistaken for Richard in the Harleian Roll. It cannot be proved from the available documentation, so the reader must use his or her own common sense and judgment. There are a couple of other armorials, which attribute the label argent (h2) to a John, but they both incorporate parts of older material and John is a recurring name. John (III) is the most likely to have been active during the lifetime of his father, if one considers their probable active periods. John (VII) is the most likely to be the John son of Richard, eight years old at the death of his father (GEC 2, p. 46), from which it follows that John (XII, d. 1388) was not born c. 1319 as proposed in most pedigrees.

5.2. The ‘Junior’ Branch with ‘Senior’ Arms

The proposal by (

Wagner 1958, p. 365) of

Gules a fess or (

j1) as the arms of the Warwick/Elmsley branch as a whole, presumably adopted by William (III, d. 1268/69) of Elmley or even one of his ancestors, is a typical problematic conclusion. Firstly, it is free of any differences, and may be an unfinished entry as is the case for Lord Marshall 38 ‘le counte de warwyke’, and in the description of a seal attributed to Thomas 3E.Warwick (DBA 3, p. 295, BirmCL sls). The entries for William (III) in Glover 81

bis (a late copy of a c. 1255 compilation), and Grimaldi 81 (c. 1350. A mix of older material) are on the same manuscript scroll and in the same hand.

The three entries for James (d. 1292), a younger son of William (III), in St. George 283 and Charles 579 with a label azure (j2) and in Charles 222 (j1) supports the hypothesis to some extent.

The ‘junior’ or James branch is not a real branch in the standard genealogy, but if one includes armorial evidence two brothers appear. Their lifespan is at present uncertain. They may have lived as late as 1380, being contemporaries of Thomas 4E.Warwick and John (X) of Kidderminster/Holt. Bernard has a lion argent in chief dx (j3) in William Jenyns 554, as a younger brother of Reynold in William Jenyns 553 with the plain arms (j1).

7. Discussion

The unsatisfactory pedigree of the Beauchamps of Holt is presented above. The main reason behind the competing presentations of the Complete Peerage and the present paper is the sporadic nature of surviving documents. Wills, inquisitions post-mortem, and property surveys are valuable for establishing lineages, but often gives only a partial view of a persons landed properties and movables—and were in any case not available (nor searched) for the present study. Where there are serious lacunae and a person appears to be nearing or even exceeding a hundred years in a near homonymous line, common sense must take over—and propose an insert.

Armory, the part of heraldry that concerns itself with coats of arms, has rarely been used to establish lineages. In part, this may be due to ignorance of the conventions associated with the design and descent of arms and associated emblems, and in part to unfamiliarity with its corpus of sources. There are also more opportunities for transposing or misplacing a name or misdating an entry in an armorial than in most legal documents, though there are multiple instances in governmental calendared documents of giving two names to the same person. On the other hand the present examination of a wide selection of armorials has demonstrated that armoury does provide unique clues to ‘lost’ members. The brothers Reynold and Bernard as undated successors to James (d. 1292) are perhaps the clearest example, but there are other indications in the literature that younger sons may have left male offspring, which kept out of the limelight and had limited resources. Such marginally gentle sub-branches may have had a single member who managed to come back into the public sphere for a single note in the surviving records.

Before concluding this survey on the use of arms by the ramified Beauchamp of Warwick (Elmley) branch, a few problems need attention.

7.1. Parentage of Roger of Bletsoe

The standard pedigree (GEC 2, p. 44) mentions that Roger (I, d. 1380) may have been a younger (possibly the fourth) son of William (III, d. 1268) of Alcester or a grandson through Giles (d. 1361) of Powick. Placing Roger in the pedigree may be used as an example of piecing odd ends together in the absence of hard facts.

Irrespective of his parentage, Roger must have been a younger son, who got all his lands through a fortunate marriage with Sybil Pateshull (d. > 1368), eldest daughter of John Pateshull (1270/91–1349) and principal coheir of her brother William (c. 1312–59, o.s.p.) and of her maternal grandparents William Grandison and Sybil de Tregoz (GEC 6, pp. 68, 10, pp. 311–16). They married in 1336/37, when Roger was mentioned as a king’s yeoman, and had three children, incl. Philip, Archdeacon of Exeter, who may be the unplaced Philip in

Figure 3, noted in the Tudor armorial Peter le Neve 259 with the basic Powick arms. Their grandson Roger (IV) was born 1363, which fits with any birth date of his father Roger (III). The pair must have been highly regarded as they were granted substantial parts, Bletsoe and Tregoz Lydiard, of the eventual inheritance as early a 1348—while both her father and brother was alive. That the latter had no children after 16 years of marriage was likely part of the reason for the early transfer of lands.

The key question is: When was Roger (I) born? If son of William (III) of Alcester, it must be no later than 1304 as a posthumous son, but for a younger son of Giles of Powick, who only married Katherine Bures in 1329, it would be no earlier than 1331. He would hardly be a king’s yeoman and marry at the tender age of six years old. On the other hand, an impecunious, but able, younger son could by good connections be able to get the hand of a fine heiress when he was in his mid-thirties and still be able to found a line. Roger (I) did have good connections to Edward III. He was summoned as a baron to Parliament in 1363. For that, not even possession

jure uxoris of a fourth part extended by previous grants of the combined inheritance of Pateshull, Grandison and Tregoz would be a sufficient reason. That part of the inheritance can be traced to Beauchamp of Bedford is just one of history’s ironies. As mentioned, website genealogy can be a help, but also filled with mistakes and pitfalls. A search was done and references to

www.geni.com (

Pateshull 2018) and

www.findagrave.com (

Beauchamp 2018) are only included to show how the basic information in the Complete Peerage and supplementary information can be differently interpreted.

One may note here the treacherous term ‘baron’. Modern usage, as noted in most entries and in the supplements to GEC (4, pp. 649–756, 5, pp. 787–91, 12.1S, pp. 2–3) presumes that peerages, with baron as the lowest rank, are hereditary. These are the parliamentary barons or lords, men summoned in person to Parliament as Lord MySurname. Contemporary practice, as evidenced for the Beauchamps and many other families, shows that such summonses were not hereditary. Male sons and heirs were often not summoned even when of age and underaged boys in wardship were never summoned. In a few instances an eldest son could be summoned during the lifetime of his father. On the other hand, a grandchild might get enough stature to be summoned either with the same title as his forebears or a new one. The word baron was seldom used as a title by contemporary officialdom. The other use of the word was as a description of wealth. A feudal baron, sometimes mentioned as baron of MyPlace, would have extensive lands, vassals and associates, and be a political power locally, as well as on a national basis. Family ties, e.g., with one of the dozens earls, would help. Men of this status would be summoned in person to ‘great councils’. These were called to discuss major policy issues, but without the interference of other legal or tax issues associated with meetings of the Parliament—and summons to great councils did not count as membership of the peerage. Burgesses and knights were also summoned or designated by sheriffs.

7.2. The Border, Trefoil and Clare Problems

Taking the latter first, the honour of Clare was one of the greatest reaching 141 knight’s fees and it (more or less) went with the earldoms of Gloucester and Hertford, at least until the Clare lineage became extinct in the male line in 1314. From that it went through Burgh and Mortimer to the royal family (

Sanders [1960] 1963, pp. 34–35). The Clare lineage was illustrious, so it would be opportune to include it among one’s ancestors even though little economic profit was likely—at least in the short run. Richard (II, d.1439, 5E.Warwick) obviously wanted to enhance his image after his marriage in 1423 to the heiress Isabel Despencer (1400–1439) by incorporating an inescutcheon of Clare quartering Despencer (

x2) in his arms on seal and other displays. She was daughter and heir of Thomas Despencer (1373–1400) E.Gloucester and his wife Constance, a daughter of Edmund D.York and a member of the royal family. Thomas E.Gloucester was attainted and executed during the Epiphany rising shortly after Henry IV assumed the crown, but by the time of the regency of his grandchild Henry VI, this and her age did not matter. The Clare arms could refer to the presumed marriage of Guy (I, d. 1315, 2E) and Isabel Clare, but she was not a principal heiress and the marriage was apparently never consummated, so the inescutcheon must refer to this Despencer marriage.

It has not been possible to find any clue for the three variants of the Clare arms placed on the Powick arms with the martlets around the fess (

g1–g3, DBA 3, p. 444,

Wagner 1958, p. 365, no. 10). The earliest evidence is apparently c. 1460 in Starkey 17 (

g2). The other entries are in Tudor armorials, mainly from the Wriothesley studio, where they are ascribed to Giles. Wagner also has it for William (V, o.s.p. c. 1353). There are no Clares in their known pedigree and no discernible person, who could claim part in any inheritance from Clare, Burgh, or Mortimer. It is likely to be a confounded brisure or damaged entry in an older source.

The trefoil brisure for a Richard in Creswick 1570 (

k1) and a number of Tudor armorials (DBA 3:416) is also hard to explain. It could be a confounded version of the crossed crosslets of the Beauchamps of Warwick and unlikely to have been used by Richard (II, 5E) after his Despencer marriage. Both candidates mentioned in

Figure 3, Richard (V, d. 1503, e1) and Richard (VI, d. 1508, f1), were barons and only sons, and as such entitled to the undifferenced arms of the sub-branch. Even in the lifetime of their fathers, there ought not to be any reason for adopting trefoil as a primary brisure when a small figure on the fess or a label as secondary brisure would be enough. If this is not a mistake by a late compiler, one may add a Richard to the unplaced members in

Figure 3.

There are four arms with a border (f1–f4) for members of the Powick branch, of which the two for members of the St. Amand sub-branch (f1, f4) are unproblematic. Though a border engrailed (f2) without any indication that someone used the plain border is surprising, it appears from the evidence in armorials (DBA 3, p. 453) that William (V, d.c. 1353), the 2nd son of Walter (III, d. 1303) of Powick did use it before 1328. It is documented 1308–14 in armorials that are unlikely to be related (Harleian 43; 1st DunsTable 90; Parliamentary 879). If this appears improbable, an unplaced William (X) needs to be introduced.

The real problem concerns Gules fess or ch. Mullet azure between 6 martlets or within a border argent (f3) and its opposite without border (e6). These two conflicting descriptions are for a brass of Walter son of William in Checkendon Church (Oxon) in DBA 3, p. 488 and 3, p. 512. It is not inconceivable that one of the transcriptors could mistake the edge of the shield for a border. If so, the brass would be for Walter (VI, fl. 1440), son of William (VII, d. < 1431) of Powick.

One of the (few) problems with the DBA is that the entries are often partial for composite arms. An entry for a given quarter may give a note of the families present in one or more quarters, but almost never the full blazon of the shield. It did not even note that the Checkendon brass consisted of three parts, angels holding his soul, a text plate and a composite shield with four quarters. Fortunately, there are images of the brass and rubbings made in 1898 floating on the internet (no URL, as it was found in the image bank). The latter is preserved at the Ashmolean Museum (ANBR Oxfordshire 252, no image) and dated 1430 in the note. The quarters are Q1+4 Beauchamp (f3, with border), Q2 St. Amand, Q3 destroyed, for which the only conclusion is that it must be an otherwise unmentioned Walter (VII), son of William (VIII, d. 1427, baron St. Amand 1449) and Elizabeth Braybrooke, and brother of Richard (VI, d. 1508) the last surviving male Beauchamp. Anthony Wagner has this Walter as d.c.1430 with the f3 arms. The remaining issue is whether Walter (VII) did die c.1430 as a child or later as a younger brother? William and Elizabeth, heiress to St. Amand lands, married c.1426 and Richard must have been born c.1453 (GEC 11, p. 303). If the mullet (f3) indicate that Walter (VII) was a younger son, he was probably born 1454/58 and may have died at anytime before 1508. The 1430 in the DBA and diverse notes in the literature could have been purloined from his grandfather Walter (V, d.c. 1430). If, on the other hand he was the first-born and named after his grandfather, he must have died before the age of ten. Giving a young child personalized arms, both quartering his mother’s inheritance and with a brisure, must be very rare—if ever recorded.

Lastly, there is a brass of 1506 (f3) in White Waltham (Berks.) for Joan, wife of Richard Decons, and daughter of an unplaced Thomas (IV) Beauchamp (DBA 3, p. 512).

7.3. Beauchamp, Pedigrees and Cadency Systems

The earliest theoretical work on the ‘law of arms’ was

De insigniis et armis by an Italian law professor Bartolus di Sassoferrato written c. 1350 (

Jones 1943, pp. 221–52;

Cavallar et al. 1994). Shortly before he died in 1357, he became councillor to Emperor Charles IV. He was a famous jurist and widely read for this, but his background in armoury was Italy and Germany, territories where cadency marks are almost never used. He was certainly read by fellow jurists and by the earliest English theoretic Johannes de Bado Aureo, a pseudonym, who published c.1395 (

Jones 1943, pp. xvii, 95–143;

Humphery-Smith 1988, pp. 97–98), but hardly used as a guideline and even less as a binding rule by any in the gentry or nobility.

Back around 1260 and on to 1500, the Beauchamps would have used common sense combined with a look at what their peers did, before adopting a specific difference. We actually do not know whether medieval brisures were adopted by the persons using them or assigned by their fathers or older brothers. One thing is certain, they were not granted by the College of Arms, the Court of the Lord Lyon, or any official institution.

The main branch (Warwick), the three sub-branches (Powick, Holt, and ‘junior’) and the three sub-sub-branches (Abergavenny, Bletsoe, and St. Amand) eschewed most of the major brisures for putting charges (minor brisures) on the single ordinary (a fess) common all arms used by the Elmley-Warwick branch. Putting charges (crosslets, martlets, and billets) denoting the primary level of juniority around this ordinary was only done once, c. 1260. The use of a label for the eldest son is so conventional that it hardly needs any notice. The border as difference may have been chosen by Walter (V, d.c. 1430), but the only evidence we have are for his two sons of the St. Amand sub-sub-branch and his grandson. The choice may have been made as no other, or better, distinctive mark was available. The family memory would hardly have indicated that the border should be re-introduced, because a great-uncle, William (V. d.c. 1353), used it a century earlier. By the 15th century the most successful members quartered or impaled the basic arms of their branch with emblems of their rank (Newburgh for earldom of Warwick), office (diocese of Salisbury) or fine marriages (Despencer, Pateshull)—the beginning of multi-quarter show-offs. Richard Neville (d. 1471), the ‘Kingmaker’, E.Warwick by his marriage to the Beauchamp heiress, managed to have three subquarters (Beauchamp, Newburgh; Montagu, Monthermer; Clare, Despencer) as Q1, 2, and 4, and the arms of his lineage only as Q3 with a label compony as a younger son (Egerton 92, Birch 6258 in variant form).