Interraciality in Early Twentieth Century Britain: Challenging Traditional Conceptualisations through Accounts of ‘Ordinariness’

Abstract

:1. Introduction

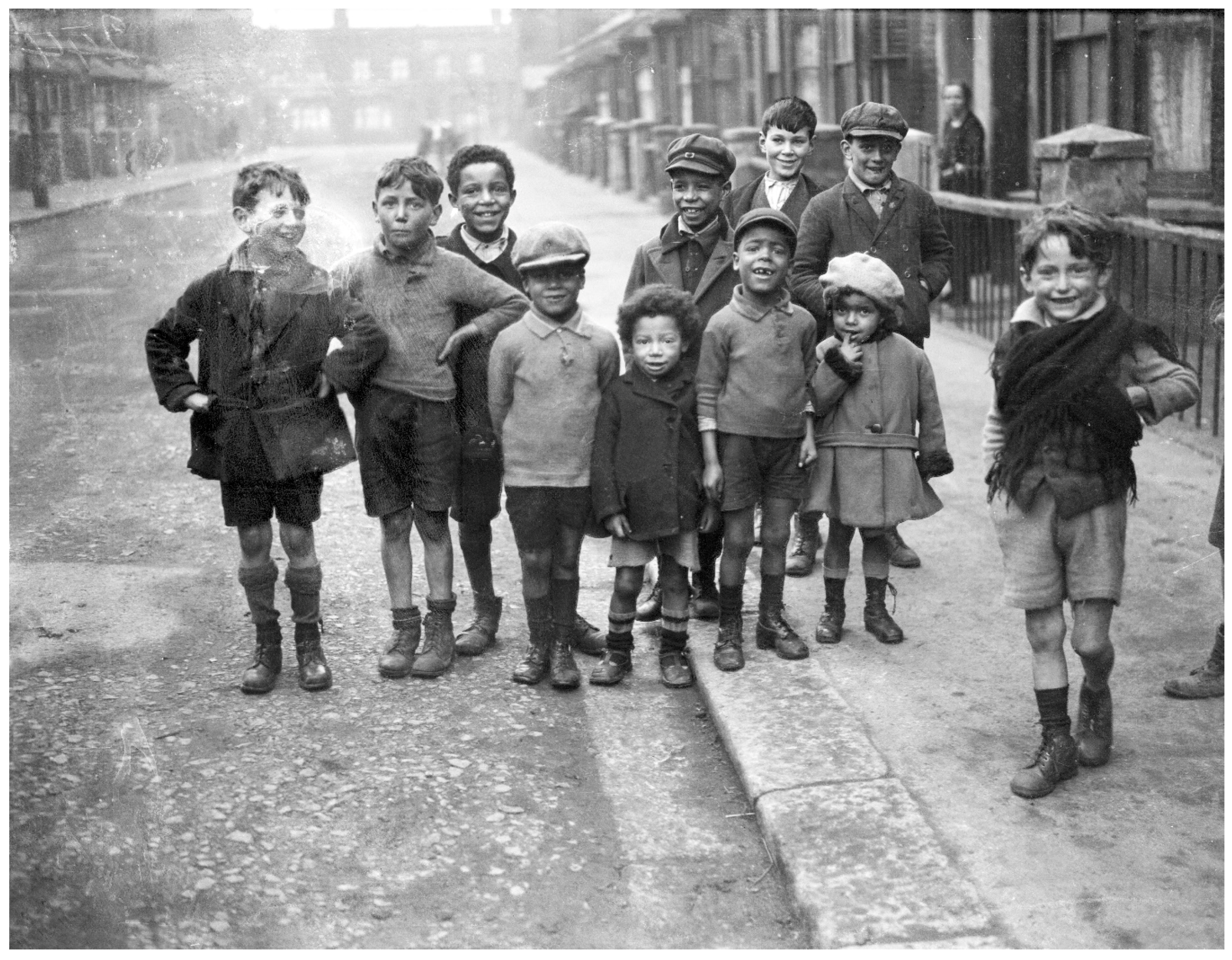

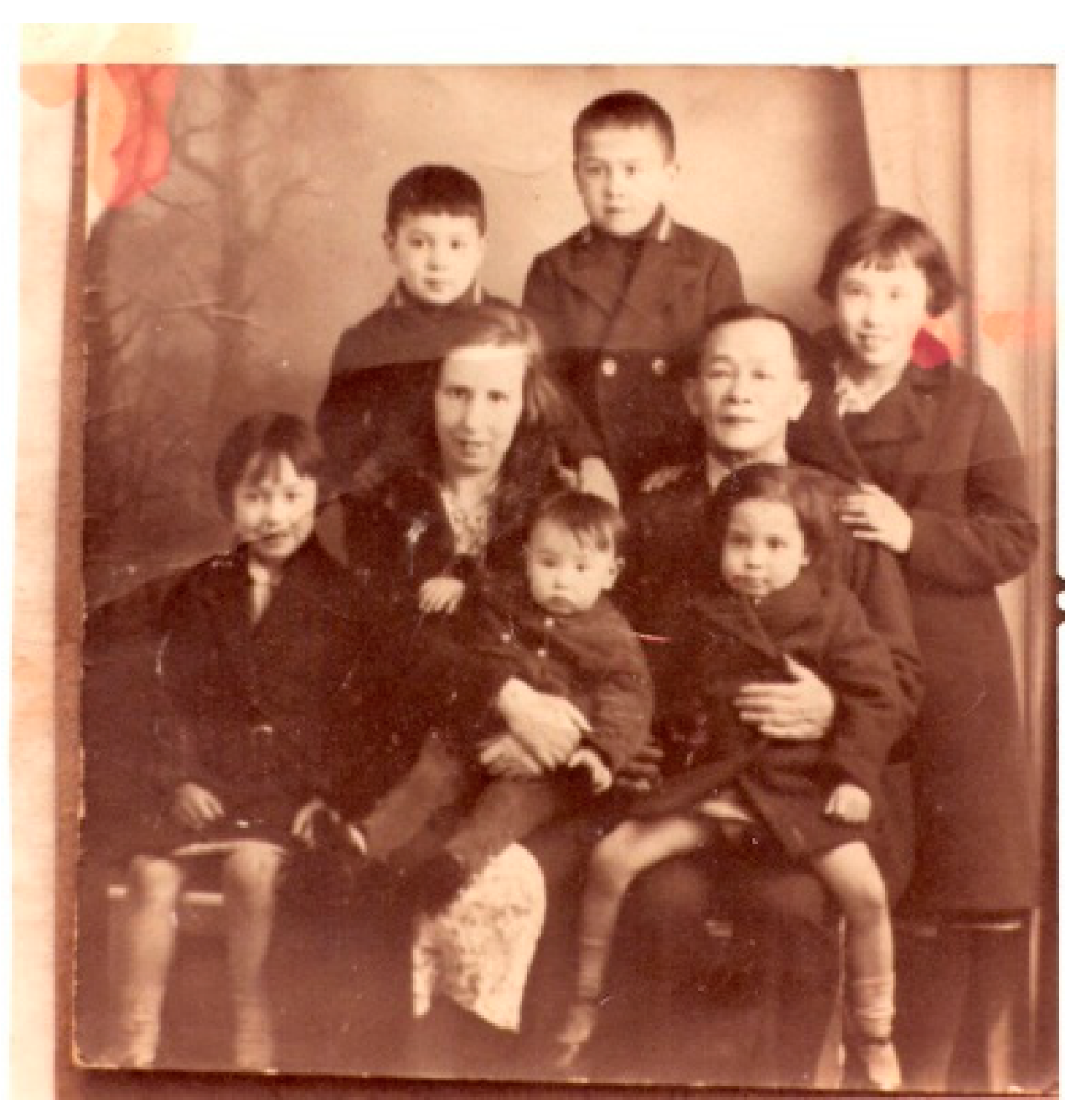

2. The ‘Ordinary’ Presence of Interraciality in Early Twentieth Century Britain

If a husband happens to be fathering another man’s child, he is not likely to know and, as they say, “what the eye does not see, the heart does not grieve over”. But what happens when his wife brings forth a black man’s child? The East Enders had hardly faced this before, but after the Second World War the potential was there.

3. Experiences of Ordinariness for Interracial Couples, Families and Peoples in Early Twentieth Century Britain

The Commonplace, the Mundane, the Everyday

We always had Sunday shoes and day school. I know that because it was my job to clean them all […] and I had to do—help with the back kitchen and clean the knives and forks. We all had something to do […]. We used to—we had a big fireplace and we used to have—of course you’d no baths like we’ve got now, used to bath in there. Lock the doors up and curtains up, we’d light the fire, heat the water on the fire and bath in there […]. We had a range in the—in middle room, it was—no gas at that time. We had a range and a—fireplace in the kitchen. And we’d plenty pots and saucepans and—plenty of—utensils of every—anything for our use […]. [For breakfast] Sunday morning we’d have salt fish and potatoes. Monday morning we’d have fry up and bacon. Tuesday morning have tripe and onions. Wednesday morning we’d have bacon and eggs. Thursday—sausage. Sausage and mash. And Fridays—my father wouldn’t have no meat in the house, we all had to have fish Fridays […]. [My mother] was a wonderful mother. Wonderful. I only wish she was alive today. Good woman. She was very affectionate, she was a good mother. Very fond of all her children, she never made—more of one than she did of the others. Nor my father either […]. My father was good too to her […]. The only thing with my father he was strict. He was very strict on where you went and where you go you know, if I’m out—go out anywhere ask—I went to ask my mother she said you’ll have to ask your father. And if he said yes I’d go and if I didn’t—if he said no that was it. When he said no he meant no […]. I used to be bossy with [my brother] see. I would be bossy and they—they resent it—they’d resent it, you see, the—and I hit him and he hit me back and that was it—father hit the two of us so we—we didn’t fight no more […]. We’d all be together Christmas Day. We could have—we had a gramophone, the old battered gramophone, ‘til had—we had a—music box. We were all allowed to sing and that, we had a good day. Plenty to eat […]. [My father’d] have a pipe three times a day but he wouldn’t—ever drank.17

Saturday night had always been our family night out—a visit to the pictures. We generally went to the Gem Cinema, the local flea-pit where we had to queue up because it was so popular. Pa always bought mother her favourite sweets, which were almonds covered with toffee […]. My mother and father were not drinkers, and they seldom went to pubs but the big treat after the pictures was a glass of brown ale. Pa would buy a bottle at the off-licence, then come home to enjoy it with mother, who’d be listening to the radio or pottering about, while we ate our fish-and-chip supper before going off to bed.

So black men married white women and quite a lot of mixed marriages turned out alright because they were good to each other. Where we lived there was no feeling that mixed marriages were wrong. The white people we lived with accepted it. I feel there is more racism here now than we ever had before the war. We never had any racism when I was young.(Anita Bowes, cited in Bourne 2001, p. 39)

There were lots of black kids. We used to play together, no animosity between any of us. There were white women married black, you know, West Indians, they were working on the boats. Got on ever so well together.… Everybody in the street used to speak to each other, and all the children used to play together. Sometimes when me and my sister’s talking, we say, “I wonder what happened to so and so,” you know. During the war a lot of them went.(cited in Caballero and Aspinall 2018, p. 142)

I grew up as the average child in the Bay of a mixed family […] and people were really lovely, they were nice people, very human, very nice. They had their ups, their downs, [...] they were just hardworking mixed families, most of whom were very well respected […]. Very few of them ever got into trouble and went to jail out of the old times. It was just a happy life, with all nations of the world [….]. I think Tiger Bay is a lovely place and I had a lovely life in it.(cited in Caballero and Aspinall 2018, p. 181)

These were the first black faces they’d ever seen in, up in the valleys […]. And believe it or not each one of them—there was four, five I think—were taken home, no questions asked, to be lodgers and to work down the pits with them in Maerdy. So you can just imagine the surprise when dad come home there and, “Look, who’s that then?” standing behind him. “He’s our new lodger, he’s going to work with me in the pits tomorrow,” like that, the first time. But to my father it was something as he told me many a time he discussed it: going into a house there and it was accepted, unheard of, like, it, they were part of the family. But then when it came to such things as bathing in front of the fire at, they had to learn to bath in front of the fire. But the neighbours used to be in and out talking. And whoever came in, they grabbed the flannel to wash their back, didn’t ask questions, like that. It took a little while for them to get used to that, but they were taken into Maerdy just as people; nothing more or less, they were judged not on their colour, but the fact they were men and were willing to work down the pit. And that was how my father came into a place called Wrgant, Wrgant Place, up in Maerdy. And that was his first home.(cited in Caballero and Aspinall 2018, p. 185)

My father was ‘Daddy Lawes’, but my mother was ‘Bopa Lawes’. And that’s how they were known until the day they died, still as ‘Daddy Lawes’ and ‘Bopa Lawes’, and you can’t get any more, what shall I say, friendly or accepted more, anything like that [...] They were accepted. My father was black, my mother was white. But that was it. They accepted them and of course as we came along, my brother and my sister as well, we were accepted as one’.(cited in Caballero and Aspinall 2018, p. 185)

I used to go down to see them. And they used to come up to us. Grandmother always came.

I think she ended up bringing her mother with us and her sister, two sisters, come with her. And one lived in (Birkensea) round the corner from us, Auntie Lilly, yeah … and that was really the only area where there were black people there so … her two sisters come down, three sisters, and she lived there with them. And I didn’t see any of her brothers, although I used to visit one up in Edge Hill somewhere. And he was alright to me but I couldn’t really remember so much about that, you know, if she had any problems because her sister lived in the house with us so that was, to me like, they must have stuck with her, I don’t know.

Annie took the others with her to where—to down Dixie—Greengate—to where the blacks lived in all these houses and rooms, you know […]. I think they all married them any road, all married coloured […]. Ooh, they was a good looking lot of girls, lovely wavy hair you know.

4. Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Ali, Suki. 2003. Mixed-Race, Post-Race: Gender, New Ethnicities and Cultural Practices. Oxford: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Ansari, Humayun. 2009. The Infidel Within: Muslims in Britain since 1800. London: Hurst & Company. [Google Scholar]

- Aspinall, Peter J. 2015. Social representations of ‘mixed-race’ in early twenty-first-century Britain: Content, limitations, and counter-narratives. Ethnic and Racial Studies 38: 1067–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aspinall, Peter J., and Miri Song. 2013. Mixed Race Identities. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Austen, Jane. 1817. Sanditon and Other Stories. Edited and introduced by Peter Washington. London: Everyman’s Library. [Google Scholar]

- Balachandran, G. 2014. Subaltern cosmopolitanism, racial governance and multiculturalism: Britain, c.1900–45. Social History 39: 528–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldwin, M. Page. 2001. Subject to Empire: Married Women and the British Nationality and Status of Aliens Act. Journal of British Studies 40: 522–56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Banton, Michael. 1955. The Coloured Quarter: Negro Immigrants in an English City. London: Jonathan Cape. [Google Scholar]

- Barn, Ravinder, and Vicki Harman, eds. 2014. Mothering, Mixed Families and Racialised Boundaries. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Bauer, Elaine. 2010. The Creolisation of London Kinship: Mixed African-Caribbean and White British Extended Families, 1950–2003. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beard, Mary. 2017. Roman Britain in Black and White. The Times Literary Supplement. Available online: https://www.the-tls.co.uk/roman-britain-black-white/ (accessed on 30 January 2019).

- Belcham, John. 2014. Before the Windrush: Race Relations in 20th Century Liverpool. Liverpool: University of Liverpool. [Google Scholar]

- Bland, Lucy. 2005. White Women and Men of Colour: Miscegenation Fears in Britain after the Great War. Gender & History 17: 29–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bland, Lucy. 2007. British Eugenics and “Race Crossing”: A Study of an Interwar Investigation. New Formations 60: 66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Bland, Lucy. 2019. Britain’s ‘Brown Babies’: The Stories of Children Born to Black GIs and White Women in the Second World War. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bloch, Howard. 1998. Canning Town Voices. London: Chalford. [Google Scholar]

- Bourne, Stephen. 2001. Black in the British Frame: The Black Experience in British Film and Television. London and New York: Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Bressey, Caroline. 2002. Forgotten histories: Three stories of black girls from Barnardo’s Victorian archive. Women’s History Review 11: 351–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bressey, Caroline. 2010. Looking for Work: The Black Presence in Britain 1860–1920. Immigrants & Minorities 28: 164–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bush, Julia. 1994. ‘The right sort of woman’: Female emigrators and emigration to the British Empire, 1890–1910. Women’s History Review 3: 385–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caballero, Chamion. 2005. ‘Mixed Race Projects’: Perceptions, Constructions and Implications of Mixed Race in the UK and USA. Ph.D. thesis, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, Chamion. 2012. From ‘Draughtboard Alley’ to ‘Brown Britain’: The ‘Ordinariness’ of Racial Mixing and Mixedness in British Society’. In International Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Mixedness and Mixing. Edited by Edwards Rosalind, Suki Ali, Chamion Caballero and Miri Song. London: Routledge, pp. 36–56. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, Chamion, and Peter Aspinall. 2018. Mixed Race Britain in The Twentieth Century. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, Chamion, Rosalind Edwards, and Shuby Puthussery. 2008. Parenting Mixed Children: Negotiating Difference and Belonging in Mixed Race, Ethnicity and Faith Families. London: Joseph Rowntree Foundation. [Google Scholar]

- Christian, Mark. 2008. The Fletcher Report 1930: A Historical Case Study of Contested Black Mixed Heritage Britishness. Journal of Historical Sociology 21: 213–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coleridge-Taylor, Jessie. 1943. Genius and Musician, S. Coleridge-Taylor 1875–1912: A Memory Sketch on Personal Reminiscences of My Husband. London: John Crowther. [Google Scholar]

- Collins, Sydney. 1957. Coloured Minorities in Britain: Studies in British Race Relations Basedon African, West Indian and Asiatic Immigrants. London: Lutterworth Press. [Google Scholar]

- Devin, Anna. 1978. Imperialism and Motherhood. History Workshop 5: 9–65. [Google Scholar]

- Dewan, Indra Angeli. 2008. Recasting Race: Women of Mixed Heritage in Further Education. Staffordshire: Trentham Books Limited. [Google Scholar]

- Edmunson Makala, Melissa. 2016. Regenerating Images of Race in Anglo-Indian Popular Dust Jackets, 1900–1950. Melissa Edmunson Makala. Available online: https://melissaedmundson.com/2016/12/12/regenerating-images-of-race-in-anglo-indian-popular-fiction-dust-jackets-1900-1950/ (accessed on 16 November 2018).

- Edwards, Rosalind, Suki Ali, Chamion Caballero, and Miri Song, eds. 2012. International Perspectives on Racial and Ethnic Mixedness and Mixing. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Evans, Neil. 1985. Regulating the reserve army: Arabs, blacks and the local state in Cardiff, 1919–45. Immigrants & Minorities 4: 68–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fryer, Peter. 1984. Staying Power: The History of Black People in Britain. London: Pluto Press. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Jeffrey. 1998. Black Edwardians: Black People in Britain 1901–1914. London and Portland: Frank Cass. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Jeffrey. 2000. Before the Windrush. History Today 50: 29–35. Available online: https://www.historytoday.com/archive/windrush (accessed on 16 April 2019).

- Habib, Imtiaz. 2008. Black Lives in the English Archives, 1500-1677: Imprints of the Invisible. Hampshire: Ashgate. [Google Scholar]

- Hammerton, James A. 1992. Cruelty and Companionship: Conflict in Nineteenth-Century Married Life. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Hareven, Tamara K. 1991. The History of the Family and the Complexity of Social Change. The American Historical Review 96: 95–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heilmann, Ann, and Margaret Beetham, eds. 2004. New Woman Hybridities: Femininity, Feminism and International Consumer Culture, 1880–1930. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Holland, David. 2017. The Social Networks of South Asian Migrants in the Sheffield Area During the Early Twentieth Century. Past & Present: A Journal of Historical Studies 236: 243–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hudgins, Nicole. 2010. A Historical Approach to Family Photograpy: Class and Individuality in Manchester and Lille, 1850–1914. Journal of Social History 43: 559–86. [Google Scholar]

- Ifekwunigwe, Jayne. 1998. Scattered Belongings. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson, Jacqueline. 2009. Black 1919: Race, Riots and Resistance in Imperial Britain. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jordan, Glenn. 2001. Tiger Bay, Picture Post and the politics of representation. In ‘Down the Bay’: Picture Post, Humanist Photography and Images of 1950s Cardiff. Edited by Glenn Jordan. Cardiff: Butetown History & Arts Centre, pp. 9–21. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph-Salisbury, Remi. 2018. Black Mixed-Race Men: Hybridity, Transatlanticity and ‘Post-Racial’ Resilience. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Kaufmann, Miranda. 2015. “Making the Beast with Two Backs”—Interracial Relationships in Early Modern England. Literature Compass 12: 22–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaufmann, Miranda. 2017. Black Tudors: The Untold Story. London: Oneworld Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Lahiri, Shompa. 2000. Indians in Britain: Anglo-Indian Encounters, Race and Identity 1880–1930. London and Portland: Frank Cass. [Google Scholar]

- Laine, Cleo. 1994. Cleo. New York: Simon and Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- Lamont, Michele, and Sada Aksartova. 2002. Ordinary Cosmopolitanisms: Strategies for Bridging Racial Boundaries among Working Class Men. Theory, Culture and Society 19: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lawless, Richard I. 1995. From Ta’izz to Tyneside: An Arab Community in the North-East of England during the Early Twentieth Century. Devon: University of Exeter Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ledger, Sally. 1995. Darkest England: The Terror of Degeneration in Fin-de-Siècle Britain. Literature & History 4: 71–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Little, Kenneth. 1972. Negroes in Britain. London: Kegan Paul, Trench, Trubner & Co. First published 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Livesay, Daniel. 2018. Children of Uncertain Fortune: Mixed-Race Jamaicans in Britain and the Atlantic Family, 1733–1833. Williamsburg: Omohundro Institute of Early American History and Culture, Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Llwyd, Alan. 2005. Cymru Ddu: Hanes Pobl Ddudon Cymru/Black Wales: A History of Black Welsh People. Cardiff: Hughes a’i Fab. [Google Scholar]

- MacKeith, Lucy. 2003. Local Black History: A beginning in Devon. Exeter: Brightsea Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mahtani, Minelle. 2014. Mixed Race Amnesia: Resisting the Romanticization of Multiraciality. Vancouver: UCB Press. [Google Scholar]

- McCarthy, Anna. 2006. From the Ordinary to the Concrete: Cultural Studies and the Politics of Scale. In Questions of Method in Cultural Studies. Edited by Mimi White and James Schwoch. Malden and Oxford: Blackwell Publishing Ltd., pp. 17–53. [Google Scholar]

- Mckenzie, Lisa. 2010. Finding Value on a Council Estate: Complex Lives, Motherhood and Exclusion. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK. [Google Scholar]

- McNeil, Daniel. 2010. Sex and Race in the Black Atlantic: Mulatto Devils and Multiracial Messiahs. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Mukerji, Chanda, and Michael Shudson. 1991. Introduction: Rethinking Popular Culture. In Rethinking Popular Culture: Contemporary Perspectives in Cultural Studies. Edited by Chanda Mukerji and Michael Shudson. Berkeley, Los Angles and London: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Newman, Karen. 1987. ‘And Wash the Ethiop White’: Femininity and the Monstrous in Othello. In Shakespeare Reproduced: The Text in History and Ideology. Edited by Jean E. Howard and Marion F. O’Connor. New York: Methuen. [Google Scholar]

- O’Mara, Pat. 2009. The Autobiography of a Liverpool Slummy. Liverpool: Bluecoat Press. First published 1933. [Google Scholar]

- Okitikpi, Toyin, ed. 2005. Working with Children of Mixed Parentage. Lyme Regis: Russell House Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Olumide, Jill. 2002. Raiding the Gene Pool: The Social Construction of Mixed Race. London: Pluto. [Google Scholar]

- Olusoga, David. 2016. Black and British: A Forgotten History. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Onyeka. 2013. Blackamoores: Africans in Tudor England, Their Presence, Status and Origins. London: Narrative Eye Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Osborne, Thomas. 1999. The ordinariness of the archive. History of the Human Sciences 12: 51–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parker, David, and Miri Song, eds. 2001. Rethinking ‘Mixed Race’. London: Pluto. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, Fiona. 2016. Fostering Mixed Race Children: Everyday Experiences of Foster Care. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Porter, Roy. 1994. London: A Social History. London: Hamish Hamilton. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, Mary Louise. 1992. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, Paul B. 1990. Race and Empire in British Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. First published 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Rodner, William S. 2012. Edwardian London through Japanese Eyes: The Art and Writings of Yoshio Makino, 1897–1915. Leiden: Koninklijke Brill NV. [Google Scholar]

- Seed, John. 2006. Limehouse Blues: Looking for Chinatown in the London Docks, 1900–40. History Workshop Journal 62: 58–85. [Google Scholar]

- Silverstone, Roger. 1994. The Power of the Ordinary: On Cultural Studies and the Sociology of Culture. Sociology 28: 991–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Graham. 1987. When Jim Crow Met John Bull: Black American Soldiers in World War II. London: I.B. Tauris & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Sollors, Werner. 2000. Introduction. In Interracialism: Black-White Intermarriage in American History, Literature, and Law. Edited by Werner Sollors. New York: Oxford University Press, pp. 3–16. [Google Scholar]

- Soloway, Richard. 1982. Counting the Degenerates: The Statistics of Race Degeneration in Early Edwardian England. Journal of Contemporary History 17: 137–64. [Google Scholar]

- Stoler, Ann. 1989. Making empire respectable: The politics of race and sexual morality in 20-century colonial cultures. American Ethnologist 16: 634–60. [Google Scholar]

- Tabili, Laura. 1994. ‘We Ask for British Justice’: Workers and Racial Difference in Late Imperial Britain. Ithaca and London: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tabili, Laura. 1996. ‘Women of a Very Low Type’: Crossing Racial Boundaries in Imperial Britain. In Gender and Class in Modern Europe. Edited by Laura L. Frader and Sonya O. Rose. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, pp. 165–90. [Google Scholar]

- Thackerey, William Makepeace. 1848. Vanity Fair. Edited with an Introduction by J. I. M Stewart. London: Penguin. [Google Scholar]

- Thicknesse, Philip. 1778. A Year’s Journey through France and Part of Spain, Vol II. London: W. Brown. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Paul. 1992. The Edwardians: The Remaking of British Society. Bloomington: Indiana University Press. First published 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Paul. 2017. The Voice of the Past: Oral History. Oxford: Oxford University Press. With Joanna Bornat. Fourth Edition. First published 1978. [Google Scholar]

- Tikly, Leon, Chamion Caballero, Jo Haynes, and John Hill. 2004. Understanding the Educational Needs of Mixed Heritage Pupils. London: Department for Education and Skills. [Google Scholar]

- Tinkler, Penny. 2013. Using Photographs in Social and Historical Research. London: Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Tizard, Barbara, and Ann Phoenix. 2002. Black, White or Mixed Race: Race and Racism in the Lives of Young People of Mixed Parentage. London: Routledge. First published 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Twine, France Winddance. 2006. Visual ethnography and racial theory: Family photographs as archives of interracial intimacies. Ethnic and Racial Studies 29: 487–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twine, France Winddance. 2010. A White Side of Black Britain: Interracial Intimacy and Racial Literacy. Durham: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Weeks, Jeffrey, Brian Heaphy, and Catherine Donovan. 2001. Same Sex Intimacies: Families of Choice and Other Life Experiments. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- White, Jerry. 2001. London in the Twentieth Century. London: Viking. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Denise. 2010. Mixed Matters: Mixed-Race Pupils Discuss School and Identity. Leicester: Troubadour Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Wong, Maria Lin. 1989. Chinese Liverpudlians: A History of the Chinese Community in Liverpool. Birkenhead: Liver Press. [Google Scholar]

- Worth, Jennifer. 2002. Call the Midwife: A True Story of the East End in the 1950s. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. [Google Scholar]

- Wynn, Neil A. 2006. ‘Race War’: Black American GIs and West Indians in Britain During the Second World War. Immigrants & Minorities 24: 324–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, Robert J. C. 1995. Colonial Desire: Hybridity in Theory, Culture and Race. London and New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Younger, Coralie. 2003. Wicked Women of the Raj: European Women Who Broke Society’s Rules and Married Indian Princes. New Delhi: HarperCollins. [Google Scholar]

| 1 | The Daily Telegraph, 28 November 2017. |

| 2 | Influenced by the concept of ‘interracialism’ introduced by Sollors (2000, p. 3) to describe social and legal attempts to ‘prohibit, contain, or deny, the presence of […] interracial sexual relations, interracial marriage and interracial descent’, the term ‘interraciality’ is used here to describe the generalised concept, state and processes of such relations, marriages and heritages. |

| 3 | For a brief overview on this public discourse, with links to further reading, see Caballero and Aspinall (2018, p. 7). |

| 4 | Evidence for the presence of people of colour in Britain dates, of course, back to Roman Britain (see, for example Fryer (1984) and Olusoga (2016)) and, as such, the case has consequently been made for interraciality also occurring from as early as this period. However, such claims have found themselves the target of heated and aggressive public debate, as seen in the wake of commentary on the inclusion of a mixed-race Roman family in a BBC educational video for schools. For an overview of the debate, including references to scholarly arguments supporting the claim to interraciality in Roman Britain, see Beard (2017). |

| 5 | A catch-all term to refer to sailors from South Asia, Southeast Asia and the Middle East. |

| 6 | From the late 1980s onwards, academic scholarship on interraciality in Britain began to be shaped by studies led by those in or from interracial relationships themselves. Accompanying this scholarship was a growth in grassroots organisations supporting interraciality as well as fictional representations of experiences of interraciality led by those in or from mixed race families. See Caballero and Aspinall (2018). |

| 7 | Caballero et al. (2008) ‘The era of moral condemnation: Mixed race people in Britain, 1920–50’, British Academy Small Grants Scheme, award number SG-47233. |

| 8 | In fact, the issue of interraciality in Britain had also arisen in mainstream public debate during the Second World War with the posting of 13,000 black American GIs throughout Britain and the so-called ‘brown babies’ that were the visible result of some of their relationships with white British women. See (Smith 1987; Wynn 2006; Caballero and Aspinall 2018; Bland 2019). |

| 9 | |

| 10 | See the ‘Strength of Our Mothers’ project, led by the National Black Arts Alliance, exploring the life experiences of white mothers in mixed relationships in Manchester spanning three generations of African migration 1940–2000 [www.ourmothers.org/our-story]; and ‘The Colour of Love: A Celebration of Mixed Race Relationships in Nottinghamshire 1940s–70s’, by St Anns Advice Centre, both funded by the Heritage Lottery Fund 2017. |

| 11 | Emerging in the late Victorian period, the population of young women who were considered to be increasingly socially, economically and sexually independent were dubbed the ‘New Woman’. The New Woman’s apparent rejection of the norms of marriage and domesticity was considered by many to be a threat to the perpetuation of the British race, nation and, consequently, Empire itself. See Heilmann and Beetham (2004). |

| 12 | |

| 13 | For further discussion of how race and interracial relationships were displayed in early twentieth century book illustration, see Edmunson Makala (2016). I am indebted to Edmunson Makala’s work for alerting me to the illustrations for Jungle Tales, Sackcloth and Ashes and Concealed Turnings. |

| 14 | It should be noted that mainstream accounts were not always and inevitably hostile. See Caballero and Aspinall (2018). |

| 15 | See also The Mix-d Museum: www.mix-d.org/museum/timeline (accessed on 31 March 2019). |

| 16 | The Family Life and Work Experience Before 1918, 1870–1973 project was undertaken by Paul Thompson and Trevor Lummis in the early 1970s. Consisting of 573 life story interviews with a cross-national sample of people born before 1918, the research formed the basis of the first national oral history project in the United Kingdom. It was initially suggested that Harriet Vincent—the daughter of a black father and white mother who ran an Edwardian boarding house in Cardiff and who appeared in Thompson’s book The Edwardians (Thompson [1975] 1992)—might have been the sister of Edith Bryan (Green 1998, p. 61) but in comparing extracts of Vincent’s interview with Edith’s transcript and taking into account Thompson [1975] (1992, p. xvi)’s note on anonymising some interviewees’ details, it seems that they are the same person and ‘Harriet Vincent’ is instead the pseudonym of Edith. |

| 17 | Edith Bryan, The Family Life and Work Experience Before 1918, 1870–1973 project. |

| 18 | Edith Bryan, The Family Life and Work Experience Before 1918, 1870–973 project. |

| 19 | Charles Jenkins, Millennium Memory Bank, 10 October 1998. |

| 20 | Mary Brady, The Family Life and Work Experience Before 1918, 1870–1973 project. |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Caballero, C. Interraciality in Early Twentieth Century Britain: Challenging Traditional Conceptualisations through Accounts of ‘Ordinariness’. Genealogy 2019, 3, 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3020021

Caballero C. Interraciality in Early Twentieth Century Britain: Challenging Traditional Conceptualisations through Accounts of ‘Ordinariness’. Genealogy. 2019; 3(2):21. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3020021

Chicago/Turabian StyleCaballero, Chamion. 2019. "Interraciality in Early Twentieth Century Britain: Challenging Traditional Conceptualisations through Accounts of ‘Ordinariness’" Genealogy 3, no. 2: 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3020021

APA StyleCaballero, C. (2019). Interraciality in Early Twentieth Century Britain: Challenging Traditional Conceptualisations through Accounts of ‘Ordinariness’. Genealogy, 3(2), 21. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3020021