The Electoral Breakthrough of the Radical Right in Spain: Correlates of Electoral Support for VOX in Andalusia (2018)

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. The State of the Art Regarding Electoral Support for Radical Right Parties

3. Methodology: Data and Hypotheses Operationalization

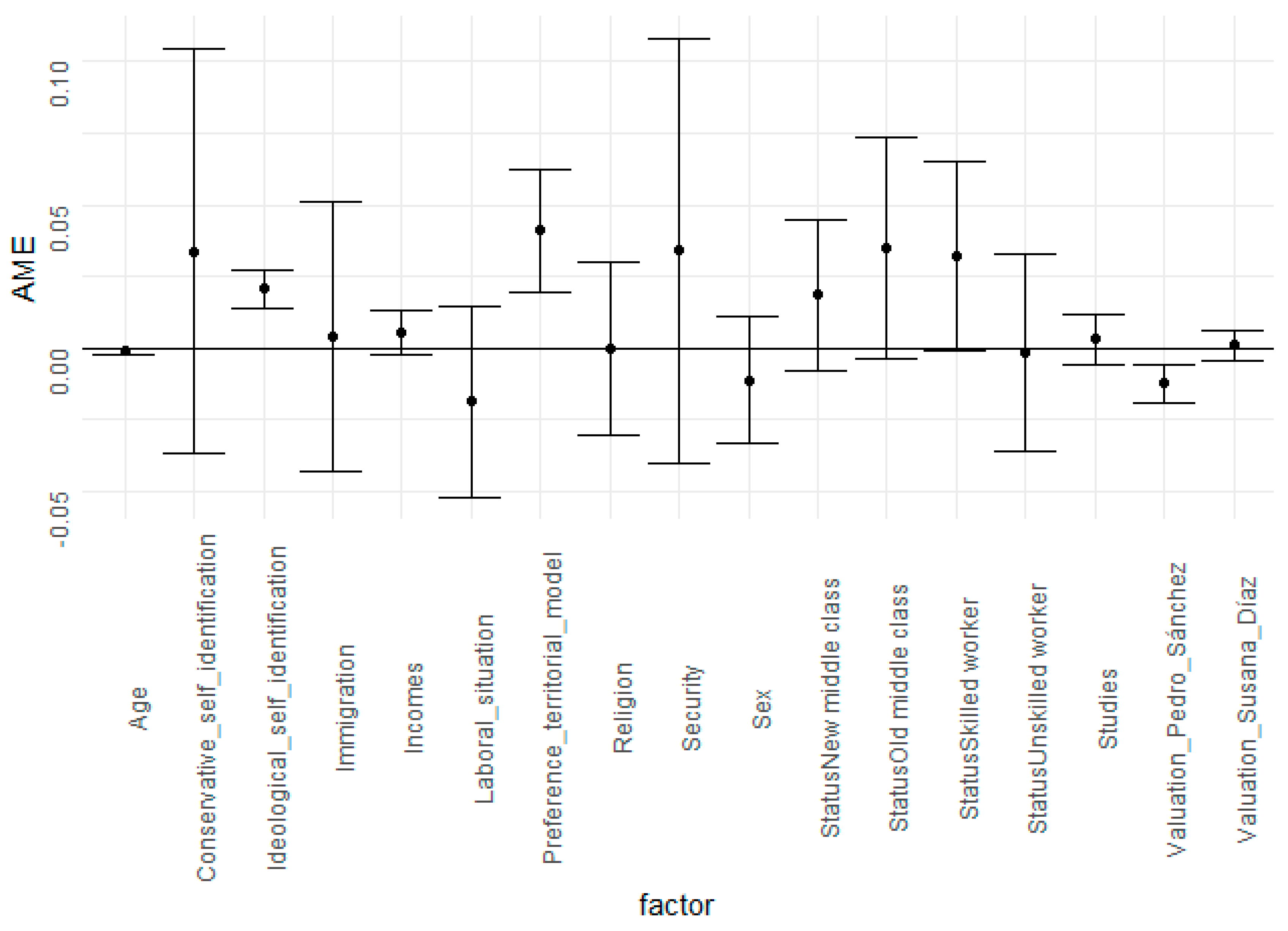

4. Discussion of Results

5. Conclusions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Variables | Categories | Mean (SD) | Min–Max. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic status | 1 = “High class/high middle class”; 2 = “new middle class”; 3 = “old middle class”; 4 = “skilled worker”; 5 = “unskilled worker” | 3.12 (1.4) | 1–5 |

| Laboral situation | 1 = “working”; 0 = “not working” | 0.66 | 0–1 |

| Incomes | 1 = “no income at all”; 2 = “less than 300 Euros”; 3 = “301–600”; 4 = ”601–900”; 5 = ”901–1.200”; 6 = “1.201–1.800”; 7 = “1.801–2.400”; 8 = “2.041–3.000”; 9 = “3.001–4.500”; 10 = “4.501–6.000”; 11 = “more than 6.000” | 3.82 (1.97) | 1–11 |

| Immigration as country first problem | 1 = “yes”; 0 = “no” | 0.02 | 0–1 |

| Religion | 1 = “catholic”; 0 = “not catholic” | 0.76 | 0–1 |

| Security as country first problem | 1 = “yes”; 0 = “no” | 0.76 | 0–1 |

| Preference about territorial model | 1 = “State with only central government and without Autonomous Communities” or “State with Autonomous Communities with less autonomy tan now”; 0 = “State with Autonomous Communities with more autonomy tan now” or “State what recognises the right to Autonomous Communities to turn into independent states” | 0.25 | 0–1 |

| Ideological self-identification | 1 (“extreme left”)–10 (“extreme right”) | 4.69 | 1–10 |

| Evaluation of Susana Díaz | 1 (“very bad”)–10 (“very good”) | 3.64 | 1–10 |

| Evaluation of Pedro Sánchez | 1 (“very bad”)–10 (“very good”) | 3.72 | 1–10 |

| Conservative self-identification | 1 = “conservative”; 0 = “others” | 0.05 | 0–1 |

| Sex | 1 = “woman”; 0 = “man” | 0.51 | 0–1 |

| Age | Free response | 48.8 | 18–96 |

| Studies level | 1 = “without studies”; 2 = “primary studies”; 3 = “secondary studies first level”; 4 = “secondary studies second level”; 5 = “professional formation”; 6 = “university or higher education” | 3.71 (1.6) | 1–6 |

References

- Acha, Beatriz. 2017. Nuevos partidos de ultraderecha en Europa Occidental: El caso de los Republikaner alemanes en Baden-Württemberg. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad Autónoma de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Acha, Beatriz. 2019a. No, no es un Partido (Neo)fascista. Agenda Pública. January 6. Available online: http://agendapublica.elpais.com/no-no-es-un-partido-neofascista/ (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Acha, Beatriz. 2019b. La Normalización Exprés de VOX. Agenda Pública. January 8. Available online: http://agendapublica.elpais.com/la-normalizacion-expres-de-vox/ (accessed on 5 November 2019).

- Allport, Gordon. 1954. The Nature of Prejudice. Reading: Addison-Wesley. [Google Scholar]

- Alonso, Sandra, and Cristóbal Rovira. 2015. Spain: No Country for the Populist Radical Right? South European Society and Politics 20: 21–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andalusian Government. 2018. Resultados Elecciones Parlamento Andalucía 2018. Available online: https://www.resultadoseleccionesparlamentoandalucia2018.es/Inicio (accessed on 15 October 2019).

- Anduiza, Eva. 2018. El discurso de VOX. Agenda Pública. December 6. Available online: http://agendapublica.elpais.com/el-discurso-de-vox/ (accessed on 20 June 2018).

- Art, David. 2011. Inside the Radical Right: The Development of Anti-Immigrant Parties in Western Europe. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Arzheimer, Kai, and Elisabeth Carter. 2009. Christian Religiosity and Voting for West European Radical Right Parties. West European Politics 32: 985–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzheimer, Kai. 2009. Contextual factors and the extreme right vote in Western Europe 1980–2002. American Journal of Political Research 53: 259–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arzheimer, Kai. 2017. Electoral sociology—Who votes for the Extreme Right and why—And when? In The Populist Radical Right. A Reader. Edited by Cas Mudde. London: Routledge, pp. 376–92. [Google Scholar]

- Barrio, Astrid, Óscar Barberá, and Juan Rodríguez-Teruel. 2018. ‘Spain steals from us!’ The ‘populist drift’ of Catalan regionalism. Comparative European Politics 16: 993–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell, Daniel. 1964. The Radical Right. Piscataway: Transactions Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Bornschier, Simon. 2010. Cleavage Politics and the Populist Right. The New Cultural Conflict in Western Europe. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Brown-Iannuzzi, Jazmin, Maxine Najle, and Will Gervais. 2019. The Illusion of Political Tolerance: Social Desirability and Self-Reported Voting Preferences. Social Psychological and Personality Science 10: 364–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Carabaña, Julio. 2016. Ricos y Pobres. Madrid: Los Libros de la Catarata. [Google Scholar]

- Carmona, Pablo, Beatriz García, and Almudena Sánchez. 2012. Spanish Neocon. La Revuelta Neoconservadora en la Derecha Española. Madrid: Traficantes de Sueños. [Google Scholar]

- Casals, Xavier. 2014. L’hora del Carajillo Party? Ara. March 15. Available online: https://www.ara.cat/premium/politica/Lhora-del-Carajillo-Party_0_1102089840.html (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Center for Sociological Research. 2019a. Serie Tres Problemas Principales que Existen Actualmente en España. Available online: http://www.cis.es/cis/export/sites/default/-Archivos/Indicadores/documentos_html/TresProblemas.html (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Center for Sociological Research. 2019b. Estudio nº 3236. Postelectoral Elecciones Autonómicas 2018. Comunidad Autónoma de Andalucía. Available online: http://www.cis.es/cis/opencm/ES/1_encuestas/estudios/ver.jsp?estudio=14440 (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- De Lange, Sarah, and David Art. 2011. Fortuyn versus Wilders: An Agency-Based Approach to Radical Right Party Building. West European Politics 34: 1229–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Givens, Terri. 2017. The radical right gender gap. In The Populist Radical Right. A Reader. Edited by Cas Mudde. London: Routledge, pp. 393–413. [Google Scholar]

- González, Pablo. 2018. Sí, la inmigración es una oportunidad. Agenda Pública. August 6. Available online: http://agendapublica.elpais.com/si-la-inmigracion-es-una-oportunidad/ (accessed on 5 November 2019).

- González-Enríquez, Carmen. 2017. The Spanish Exception: Unemployment, Inequality and Immigration, but No Right-Wing Populist Parties. Working Paper. Madrid, Spai: Real Instituto Elcano. Available online: http://www.realinstitutoelcano.org/wps/portal/rielcano_es/contenido?WCM_GL%2520OBAL_CONTEXT=/elcano/elcano_in/zonas_in/ari47-2016-gonzalezenriquez-highs-%2520lows-immigrant-integration-spain (accessed on 15 August 2019).

- Gould, Robert. 2019. Vox España and Alternative für Deutschland: Propagating the Crisis of National Identity. Genealogy 3: 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Griffin, Roger. 2000. Interregnum or endgame? The Radical Right in the ‘Post-Fascist’ Era. Journal of Political Ideologies 5: 163–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, Kirk, and Cristóbal Rovira. 2019. Introduction: the ideational approach. In The Ideational Approach to Populism: Concept, Theory and Analysis. Edited by Kirk Hawkins, Ryan Carlin, Levente Littvay and Cristóbal Rovira. London: Routledge, pp. 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Ignazi, Piero. 1992. The Silent Counter Revolution: Hypotheses on the Emergence of the Extreme Right-Wing Parties in Europe. European Journal of Political Research 22: 3–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immerzeel, Tim, and Mark Pickup. 2015. Populist radical right parties mobilizing ‘the people’? The role of populist radical right success in voter turnout. Electoral Studies 40: 347–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linz, Juan, and José R. Montero. 1999. The Party Systems of Spain: Old Cleavages and New Challenges. Working Paper. Madrid, Spain: Juan March Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Llamazares, Iván, and Luis Ramiro. 2006. Les espaces politiques restreints de la droite radicale espagnole. Une analyse des facteurs politiques de la faiblesse de la nouvelle droite en Espagne. Pôle Sud 25: 1262–676. [Google Scholar]

- Llamazares, Iván. 2012. La communauté nationale menacée. Inertie et transformations de l’idéologie ultranationaliste de l’extrême droite espagnole. In Les Nationalismes Dans l’Espagne Contemporaine (1975–2011). Compétition Politique et Identités Nationales. Edited by Alicia Fernández and Mathieu Petithomme. Paris: Armand Colin, pp. 77–102. [Google Scholar]

- Ministry for Home Affairs. 2019. Resultados Elecciones Parlamento Europeo 2014. Available online: http://www.infoelectoral.mir.es/infoelectoral/min/busquedaAvanzadaAction.html (accessed on 6 July 2019).

- Moreno, Luis. 1995. Multiple Ethnoterritorial Concurrence in Spain. Nationalism and Ethnic Politics 1: 11–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, Cas. 1999. The single-issue party thesis: extreme right parties and the immigration issue. West European Politics 22: 182–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, Cas. 2004. The Populist Zeitgeist. Government and Opposition 39: 531–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, Cas. 2007. Populist Radical Right Parties in Europe. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mudde, Cas. 2014. Fighting the System? Populist Radical Right Parties and Party System Change. Party Politics 20: 217–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudde, Cas. 2019. The Far Right Today. Cambridge: Polity. [Google Scholar]

- Muñoz, Jordi. 2008. From National Catholicism to Democratic Patriotism? An Empirical Analysis of Contemporary of Spanish National Identity. Ph.D. dissertation, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- National Statistics Institute. 2019a. España en Cifras 2019. Available online: https://www.ine.es/prodyser/espa_cifras (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- National Statistics Institute. 2019b. Padrón Municipal por Municipios. Available online: http://www.ine.es/dynt3/inebase/es/index.htm?type=pcaxis&path=/t20/e245/p08/&file=pcaxis&dh=0&capsel=1 (accessed on 6 August 2019).

- Norris, Pippa. 2005. Radical Right: Voters and Parties in the Electoral Market. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Olalla, Sergio, Enrique Chueca, and Javier Padilla. 2019. Cómo cubrieron a VOX los medios tradicionales. Agenda Pública. January 14. Available online: http://agendapublica.elpais.com/como-cubrieron-vox-los-medios-tradicionales/ (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Pardos-Prado, Sergi, and Joaquim Molins. 2009. The emergence of right-wing radicalism at the local level in Spain: The Catalan case. International Journal of Iberian Studies 22: 201–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plattner, Marc. 2010. Populism, Pluralism and liberal democracy. Journal of Democracy 21: 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinken, Sebastian. 2016. Economic crisis and anti-immigrant sentiment: The case of Andalusia. Revista Española de Investigaciones Sociológicas 156: 77–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, José Luis. 1992. La Extrema Derecha en España: Del Tardofranquismo a la Consolidación de la Democracia. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad Complutense de Madrid, Madrid, Spain. [Google Scholar]

- Ros, Virginia. 2018. Nada que ver aquí; las actitudes hacia la inmigración y el auge de VOX. Agenda Pública. December 4. Available online: https://www.eldiario.es/autores/virginia_ros/ (accessed on 10 November 2019).

- Rydgren, Jens, ed. 2013. Class Politics and the Radical Right. New York: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Rydgren, Jens. 2007. The sociology of the radical right. Annual Review of Sociology 33: 241–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sánchez-Cuenca, Ignacio. 2018. VOX y nacionalismo español. Infolibre. December 5. Available online: https://www.infolibre.es/noticias/opinion/columnas/2018/12/05/vox_nacionalismo_espanol_89529_1023.html (accessed on 20 June 2018).

- Schwander, Hanna, and Philip Manow. 2017. It’s Not the Economy, Stupid! Explaining the Electoral Success of the German Right-Wing Populist AfD. Working Paper. Zurich, Switzerland: Center for Comparative and International Studies. Available online: https://www.zora.uzh.ch/id/eprint/143147/ (accessed on 5 October 2019).

- Schmitt, Hermann, Sara Hobolt, Wouter van der Brug, and Sebastian Popa. 2019. European Election Study 2019, Voter Study. Available online: http://europeanelectionstudies.net/european-election-studies/ees-2019-study/voter-study-2019 (accessed on 20 November 2019).

- Taguieff, Pierre-André. 1990. The New Cultural Racism in France. Telos 83: 109–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VOX. 2018. 100 Medidas Para la España Viva. Available online: https://www.voxespana.es/biblioteca/espana/2018m/gal_c2d72e181103013447.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- VOX. 2019. Propuestas de VOX Para la Investidura del Presidente de la Junta de Andalucía. Available online: https://www.voxespana.es/biblioteca/propuesta-vox-andalucia.pdf (accessed on 20 June 2019).

- Zubero, Imanol. 2019. Irrupción de la extrema derecha española. Galde. March 20. Available online: https://www.galde.eu/es/irrupcion-de-la-extrema-derecha-espanola/ (accessed on 15 June 2019).

| 1 | Despite significant individual victories, the true trend that characterizes the far right in Europe is the temporal and geographical variability of its performance over time. Authors such as Acha (2017), Art (2011) or Arzheimer (2009) have pointed out the bias in the literature, which focuses mainly on successful cases and ignores failures (which are more numerous and representative). |

| 2 | In October 2019, the far right party CHEGA won a set in the parliament. However, the far right remains marginal in Portugal. |

| 3 | However, as noted by Acha (2019a), VOX has two characteristics that set it apart from dominant radical right expression in other European countries: first, the anti-immigrant component is comparatively much weaker (and in any case subject to the main pillar of ultra-nationalism and the defence of Spanish identity); secondly, it is not possible to clearly identify populist elements (people-centrism, anti-elitism or Manicheism, as noted by the ideational perspective (Hawkins and Rovira 2019). |

| 4 | Elections took place in: Aragón, Principado de Asturias, Islas Baleares, Canarias, Cantabria, Castilla-La Mancha, Castilla y León, Extremadura, Comunidad de Madrid, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, Región de Murcia, La Rioja and Comunidad Valenciana. VOX did not stand for elections in Aragón, Islas Baleares, Comunidad Foral de Navarra and La Rioja. |

| 5 | Elections took place in: Aragón, Principado de Asturias, Islas Baleares, Canarias, Cantabria, Castilla-La Mancha, Castilla y León, Extremadura, Comunidad de Madrid, Comunidad Foral de Navarra, Región de Murcia y La Rioja. VOX stood for elections in all Autonomous Communities. |

| 6 | From the point of view of its organizational roots, VOX was officially registered as a political party in December 2013, when a small group of individuals with ties to the People’s Party (PP) decided to create a new political alternative as a result of their dissatisfaction with what they perceived as the PP drifting to the center. The core of people who started VOX came from the PP’s more conservative sectors. They were aligned with the former Prime Minister José María Aznar and the right-wing think-tank so-called Foundation for Analysis and Social Studies (FAES) (Casals 2014; Carmona et al. 2012). |

| 7 | We conducted some robustness checks in the four regression models: both backwards and forwards introduction of variables. These results are coherent with the “enter method” used in this analysis and are available upon request. |

| 8 | Self-reported vote is commonly used in political research, but is not exempt from biases (social desirability, for example), as noted by Brown-Iannuzzi et al. (2019). |

| 9 | We recognize this is not the best way to measure anti-immigrant or authoritarian attitudes, but it is the only option provided by CIS 3236. We acknowledge this limitation. Undoubtedly, a better option is to measure the respondent’s issue position using a 0–10 scale from fully in favour of restrictive policy on immigration to fully opposed to restrictive policy on immigration as does the European Election Studies, for example (see Schmitt et al. 2019). |

| 10 | It should be noted that the significance disappears when using listwise deletion. |

| Elections | Votes | % Votes | Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| European Parliament (May 2014) | 246,833 | 1.57% | 0 |

| Parliament of Andalusia (March 2015) | 18,017 | 0.45% | 0 |

| Local elections (May 2015) | 50,195 | 0.25% | 22 |

| Regional elections (May 2015)4 | 74,531 | 0.39% (mean) | 0 |

| National elections (December 2015) | 58,114 | 0.23% | 0 |

| National elections (June 2016) | 47,182 | 0.2% | 0 |

| Parliament of Andalusia (December 2018) | 395,978 | 10.97% | 12 |

| National elections (April 2019) | 2,677173 | 10.25% | 24 |

| Parliament of Valencia (April 2019) | 278,947 | 10.44% | 10 |

| Local elections (May 2019) | 659,736 | 2.9% | 530 |

| Regional elections5 (May 2019) | 684,312 | 5.74% (mean) | 27 |

| European Parliament (May 2019) | 1,388,681 | 6.2% | 3 |

| National elections (November 2019) | 3,639,772 | 15.09% | 52 |

| Party | Votes | % Votes | Seats |

|---|---|---|---|

| PSOE-A | 1,009,243 | 27.95% | 33 |

| PP | 749,275 | 20.75% | 26 |

| Cs | 659,631 | 18.27% | 21 |

| AA | 584,040 | 16.18% | 17 |

| VOX | 395,978 | 10.97% | 12 |

| PACMA | 69,660 | 1.93% | 0 |

| AxSÍ | 22,017 | 0.61% | 0 |

| EQUO-INICIATIVA | 15,009 | 0.42% | 0 |

| Others | 48,957 | 1.37% | 0 |

| Variables | Model 1 | Model 2 | Model 3 | Model 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Socioeconomic status ^ | ||||

| New middle class | 0.385 (0.283) | 0.481 (0.395) | ||

| Old middle class | 0.363 (0.330) | 0.389 (0.395) | ||

| Skilled worker | 0.071 (0.287) | 0.730 * (0.355) | ||

| Unskilled worker | −0.828 (0.432) | 0.012 (0.496) | ||

| Laboral situation | −0.403 (0.285) | −0.409 (0.339) | ||

| Incomes | 0.206 * (0.070) | 0.119 (0.078) | ||

| Immigration | 1.283 *** (0.354) | 0.373 (0.510) | ||

| Religion | 0.728 * (0.273) | 0.212 (0.33) | ||

| Security | 0.833 (0.749) | 0.233 (0.850) | ||

| Preference relating to territorial model | 1.210 *** (0.229) | 1.035 *** (0.229) | ||

| Ideological self-identification | 0.284 *** (0.072) | 0.532 *** (0.069) | ||

| Evaluation Susana Díaz | −0.064 (0.053) | −0.036 (0.058) | ||

| Evaluation Pedro Sánchez | −0.287 *** (0.062) | −0.257 *** (0.066) | ||

| Conservative self-identification | 1.432 (0.755) | 0.745 (0.811) | ||

| Sex | −0.257 (0.234) | |||

| Age | −0.026 *** (0.008) | |||

| Studies | 0.056 (0.088) | |||

| Constant | −3.778 *** (0.359) | −3.787 *** (0.255) | −4.570 *** (0.524) | −5.659 *** (0.860) |

| R² of Nagelkerke | 0.030 | 0.024 | 0.236 | 0.336 |

| Observations | 2913 | 2913 | 2913 | 2913 |

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ortiz Barquero, P. The Electoral Breakthrough of the Radical Right in Spain: Correlates of Electoral Support for VOX in Andalusia (2018). Genealogy 2019, 3, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040072

Ortiz Barquero P. The Electoral Breakthrough of the Radical Right in Spain: Correlates of Electoral Support for VOX in Andalusia (2018). Genealogy. 2019; 3(4):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040072

Chicago/Turabian StyleOrtiz Barquero, Pablo. 2019. "The Electoral Breakthrough of the Radical Right in Spain: Correlates of Electoral Support for VOX in Andalusia (2018)" Genealogy 3, no. 4: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040072

APA StyleOrtiz Barquero, P. (2019). The Electoral Breakthrough of the Radical Right in Spain: Correlates of Electoral Support for VOX in Andalusia (2018). Genealogy, 3(4), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy3040072