“Then Who Are You?”: Young American Indian and Alaska Native Women Navigating Cultural Connectedness in Dating and Relationships

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. Cultural Connectedness and Identity among AI/AN Adolescents

1.2. Citizenship within Settler Colonial Systems

1.3. Present Study

1.4. Legibility, Credibility, and Reclamation

2. Methods

2.1. Sampling and Recruitment

2.2. Data Collection

2.3. Qualitative Analysis

2.4. Reclaiming the Discussion

3. Results

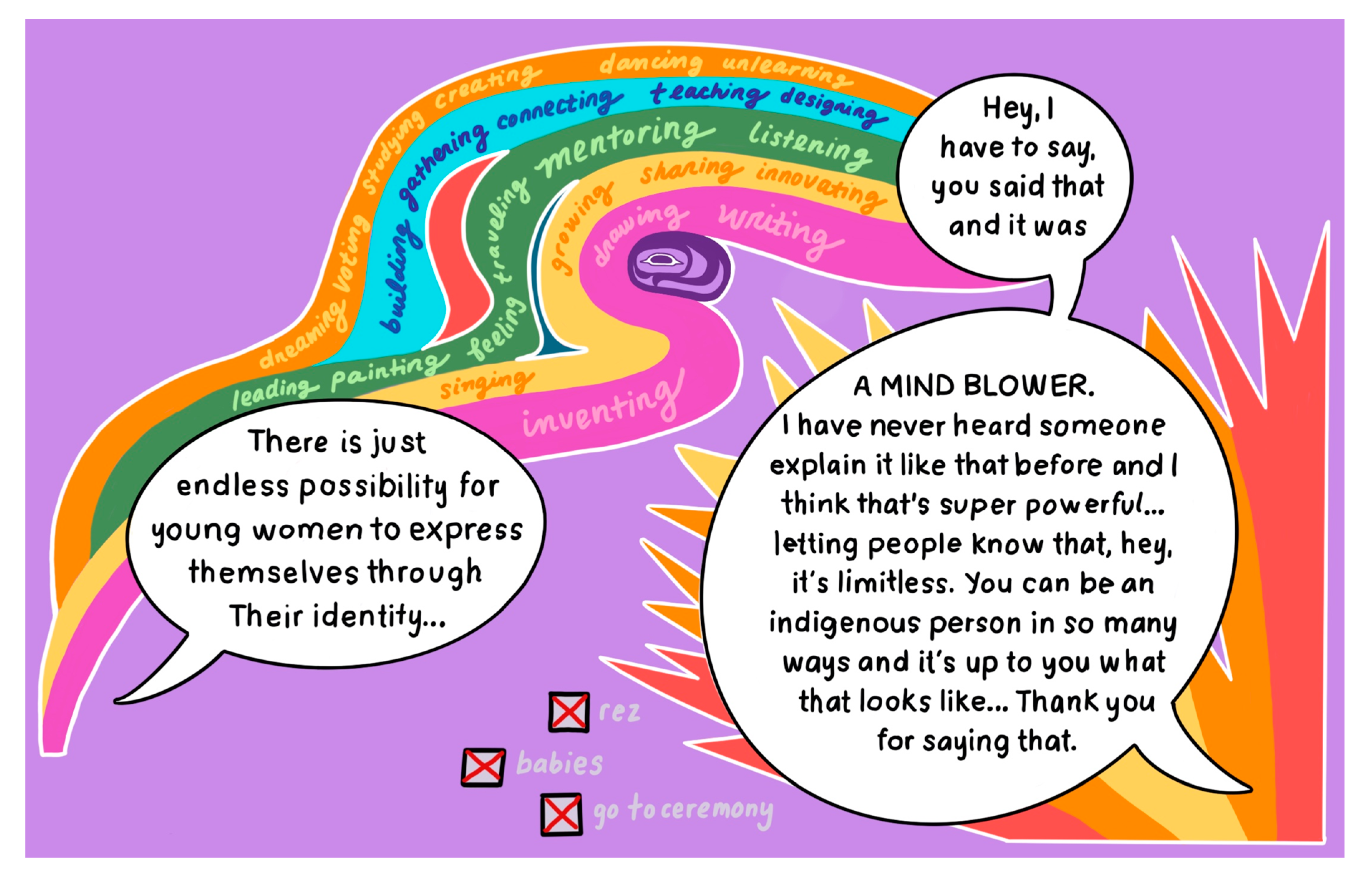

3.1. Individual Identity & Connectedness

3.2. “You Gotta Think about How You’re Gonna Raise Your Kids”: Reproductive Partners

I wouldn’t be who I am today if I was never involved, or who I am, because I’d be so different … I’d be very different if I didn’t do any of the things I do. I’d look White and then act White too.

3.3. “It’s Just a Choice You Need to Make”: Citizenship & Recognition

I guess I would be harder on them, because they would be the last legal cutoff line for legally Native, and so… if I had kids that didn’t have a Native father, I’d probably be harder on them about it. I can imagine myself in the future, just being like, “Now you HAVE to get someone that’s Native.

4. Discussion

Stories have the power to make our hearts, minds, bodies, and spirits work together.

4.1. Stories We Have Been Told & Those We Tell

4.1.1. Identity

4.1.2. Trauma

We really have to honor those things, those things that our grandmothers and our aunties [passed on] and we can honor those things and we can hold those things up, while still questioning them. And I think our aunties would be proud of us for questioning.

4.2. Stories We Need to Tell: Implications

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Anderson, Kim. 2000. A Recognition of Being: Reconstructing Native Womanhood. Toronto: Second Story Press. [Google Scholar]

- Archibald, Jo-Ann. 2008. Indigenous Storywork: Educating the Heart, Mind, Body, and Spirit. Vancouver: UBC Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, Julie A., Betty G. Brown, Heidi A. Wayment, Ramona Antone Nez, and Kathleen M. Brelsford. 2011. Culture and context: Buffering the relationship between stressful life events and risky behaviors in American Indian youth. Substance Use and Misuse 46: 1380–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baskin, Cyndy. 2020. Contemporary Indigenous women’s roles: Traditional teachings or internalized colonialism? Violence Against Women 26: 2083–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2009. High School Risk Behavior Survey. Available online: http://apps.nccd.cdc.gov/YouthOnline/App/Default.aspx (accessed on 11 January 2017).

- Chandler, Michael J., and Christopher E. Lalonde. 2008. Cultural continuity as a moderator of suicide risk among Canada’s First Nations. In Healing Traditions: The Mental Health of Aboriginal Peoples in Canada. Edited by L. J. Kirmayer and G. Valaskakis. Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, pp. 221–48. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, Victoria, and Virginia Braun. 2017. Thematic analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology 12: 297–98. [Google Scholar]

- Coker, Ann L., Bonnie S. Fisher, Heather M. Bush, Suzanne C. Swan, Corrine M. Williams, Emily R. Clear, and Sarah DeGue. 2015. Evaluation of the Green Dot Bystander Intervention to reduce interpersonal violence among college students across three campuses. Violence Against Women 21: 1507–27. [Google Scholar]

- Doerfler, Jill. 2015. Those Who Belong: Identity, Family, Blood, and Citizenship among the White Earth Anishinaabeg. East Lansing: Michigan State University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Exner-Cortens, Deinera, John Eckenrode, and Emily Rothman. 2013. Longitudinal associations between teen dating violence victimization and adverse health outcomes. Pediatrics 131: 71–78. [Google Scholar]

- Galliher, Renee V., Matthew D. Jones, and Angie Dahl. 2011. Concurrent and longitudinal effects of ethnic identity and experiences of discrimination on psychosocial adjustment of Navajo adolescents. Developmental Psychology 47: 509–26. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez, Anu Manchikanti. 2011. Testing the cycle of violence hypothesis: Child abuse and adolescent dating violence as predictors of intimate partner violence in young adulthood. Youth & Society 43: 171–92. [Google Scholar]

- Hautala, Dane S., Kelly J. Sittner Hartshorn, Brian Armenta, and Les Whitbeck. 2017. Prevalence and correlates of physical dating violence among North American Indigenous adolescents. Youth & Society 49: 295–317. [Google Scholar]

- Howard, Donna E., Min Qi Wang, and Fang Yan. 2007. Psychosocial factors associated with reports of physical dating violence among US adolescent females. Adolescence 42: 311–24. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobsen, Kristina, and Shirley Ann Bowman. 2019. “Don’t even talk to me if you’re Kinya’áanii [Towering House]”: Adopted clans, kinship, and “blood” in Navajo Country. Native American and Indigenous Studies 6: 43–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, Matthew D., and Renee V. Galliher. 2007. Ethnic identity and psychosocial functioning in Navajo adolescents. Journal of Research and Adolescence 17: 683–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markstrom, Carol A. 2011. Identity formation of American Indian adolescents: Local, national, and global considerations. Journal of Research on Adolescence 21: 519–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mihesuah, Devon Abbott. 2003. Indigenous American Women: Decolonization, Empowerment, Activism. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mohatt, Nathaniel V., Carlotta Ching Ting Fok, Rebekah Burket, David Henry, and Jim Allen. 2011. Assessment of awareness of connectedness as a culturally-based protective factor for Alaska Native youth. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 17: 444–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Montana Office of Public Instruction. 2015. Montana Youth Risk Behavior Survey: High School Results. Available online: http://opi.mt.gov/pdf/YRBS/15/15MT_YRBS_FullReport.pdf (accessed on 11 January 2017).

- Morgan, David L. 1997. Focus Groups as Qualitative Research. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Njeze, Chinyere, Kelley Bird-Naytowhow, Tamara Pearl, and Andrew R. Hatala. 2020. Intersectionality of resilience: A strengths-based case study approach with Indigenous youth in an urban Canadian context. Qualitative Health Research 30: 2001–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padgett, Deborah K. 2017. Qualitative Methods in Social Work Research, 3rd ed. Los Angeles: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Pesantubbee, Michelene E. 1999. Beyond domesticity: Choctaw women negotiating the tension between Choctaw culture and protestantism. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 67: 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ratteree, Kathleen, and Norbert S. Hill, eds. 2017. The Great Vanishing Act: Blood Quantum and the Future of Native Nations. Golden: Fulcrum Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Risling Baldy, Cutcha. 2018. We Are Dancing for You: Native Feminisms & the Revitalization of Women’s Coming-of-Age Ceremonies. Seattle: University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Rosay, André B. 2016. Violence against American Indian and Alaska Native Women and Men: 2010 Findings from the National Intimate Partner and Sexual Violence Survey. Retrieved from Washington, DC. Available online: https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/nij/249736.pdf (accessed on 8 July 2016).

- Saldaña, Johnny. 2009. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. London: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, Katie, Lauren B. Cattaneo, Chiara Sabina, Lisa Brunner, Sabeth Jackson, and Josie V. Serrata. 2016. Key roles of community connectedness in healing from trauma. Psychology of Violence 6: 42–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- TallBear, Kim. 2013. Native American DNA: Tribal Belonging and the False Promise of Genetic Science. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- TallBear, Kim. 2018. Making love and relations beyond settler sex and family. In Making Kin Not Population. Edited by Adele E. Clarke and Donna Haraway. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, pp. 145–64. [Google Scholar]

- TallBear, Kim, and Angela Willey. 2019. Critical relationality: Queer, Indigenous, and multispecies belonging beyond settler sex & nature. Imaginations 10: 5–15. [Google Scholar]

- Ullrich, Jessica Saniguq. 2019. For the love of our children: An Indigenous connectedness framework. AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples 15: 121–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, Karina L., and Jane M. Simoni. 2002. Reconceptualizing Native women’s health: An “indigenist” stress-coping model. American Journal of Public Health 92: 520–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walters, Karina L., Ramona Beltrán, Tessa Evans-Campbell, and Jane M. Simoni. 2011. Keeping our hearts from touching the ground: HIV/AIDS in American Indian and Alaska Native women. Women’s Health Issues 21: S261–S265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Whitbeck, Les B., Barbara J. McMorris, Dan R. Hoyt, Jerry D. Stubben, and Teresa LaFromboise. 2002. Perceived discrimination, traditional practices, and depressive symptoms among American Indians in the upper Midwest. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 43: 400–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolfe, Patrick. 2006. Settler colonialism and the elimination of the Native. Journal of Genocide Research 8: 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | When referring more broadly to the population we use AI/AN, but we also use the term Native because unless referring to a specific tribe, that is a more common term. Native is also how we phrased the focus group questions and the term used by participants. |

| 2 | Full quote: You just don’t want to forget where you come from and your cultural practices, just because someone … thinks it’s weird, or doesn’t understand it. I know it can be easy to fall in love with someone and be like, “Oh, I want to conform to whatever they want, so I can be with them.” And then you’ll stray away from who you are, and then if it doesn’t work out, then who are you? |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schultz, K.; Noyes, E. “Then Who Are You?”: Young American Indian and Alaska Native Women Navigating Cultural Connectedness in Dating and Relationships. Genealogy 2020, 4, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4040117

Schultz K, Noyes E. “Then Who Are You?”: Young American Indian and Alaska Native Women Navigating Cultural Connectedness in Dating and Relationships. Genealogy. 2020; 4(4):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4040117

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchultz, Katie, and Emma Noyes. 2020. "“Then Who Are You?”: Young American Indian and Alaska Native Women Navigating Cultural Connectedness in Dating and Relationships" Genealogy 4, no. 4: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4040117

APA StyleSchultz, K., & Noyes, E. (2020). “Then Who Are You?”: Young American Indian and Alaska Native Women Navigating Cultural Connectedness in Dating and Relationships. Genealogy, 4(4), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy4040117