4.1. Objective Impact of the Great Recession

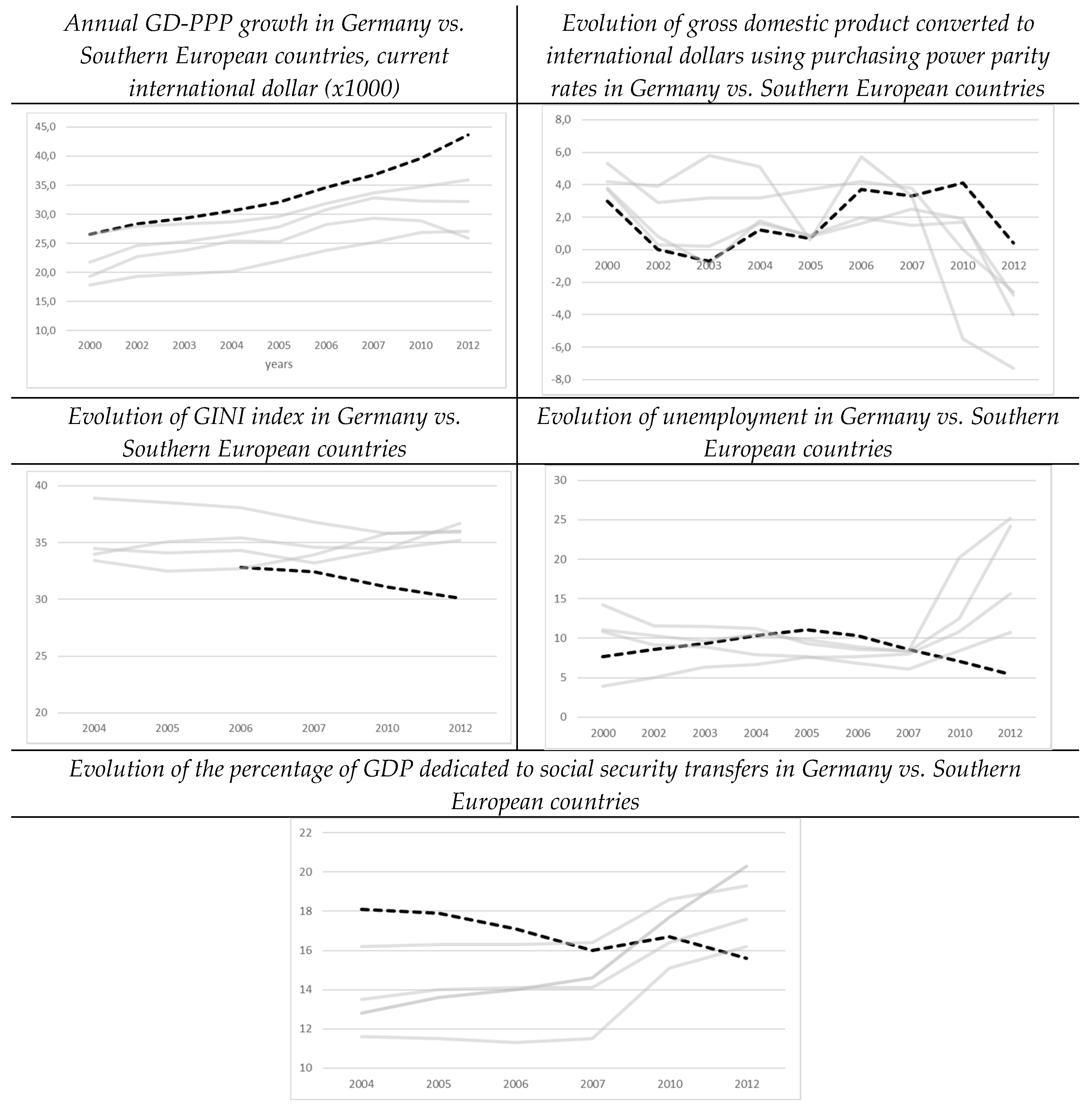

The previous sections have explained the different impacts of the Great Recession in our five cases. In general, Germany has fared better through the period, while Greece has suffered the most. In this section, we focus on the possible effect of the economic crisis on national identities at an aggregated (i.e., country) level.

When looking at how national attachment has changed during this period, the differences between Germany and the selected Southern European countries are immediately apparent. As seen in

Figure 4, only German citizens have a percentage of feeling very close to the nation that increased (by 10%) between 2006 and 2012. In Spain, Italy, Greece, and Portugal, the percentage of citizens who felt very attached to the nation decreased between around 2% (Portugal and Italy) and 5% (Greece) in the same period (

Figure 4), supporting H1 at first glance. The percentages in this figure for 2006 and 2012 are slightly different to those reported in

Appendix A. In

Figure 4, we use the specific EB that is later used in the regression. In the

Appendix A, we take the data from the GESIS EB aggregated time series. Thus, for example, the data given for 2006 are based in EB 3/2006, while for our regression, we use EB 10/2006 (EB 65.2).

Table 1 shows that not only has national identity improved in Germany but also the distances between different levels of attachment between different groups of people, as measured by the standard deviation in

Table 1, have decreased, where more people feel very close to the nation. On the other extreme, Greece has experienced the highest loss in the percentage of citizens very attached to the nation, a result that was more consistent among Greek citizens in 2012 than 2006 (see the standard deviation in

Table 1). In Spain, Italy, and Portugal, the national identity situations have also worsened and the distances between the levels of attachment among different groups of people have increased (see standard deviation in

Table 1). This points toward certain levels of polarization in national identities in 2012 as compared to 2006 in Spain, Italy, and Portugal.

If we consider the standard errors of the sample, only the changes for Germany are statistically significant. The sample sets consist of around 1000 individuals on average for the different countries, where, considering a confidence interval of 95% (p = q = 50%), the standard error would be +3.1. Only the 10% change in Germany between 2006 and 2012 is larger than the error. The changes in Spain and Italy would be on the limit for a confidence interval of 90%. Thus, we cannot argue that there have been significant changes in the percentages of strong national identity holders in the selected Southern European countries, while the change in Germany might also be modest when discounting the standard error. In summary, these findings are consistent with H1 regarding both the modest amount of change and the directions of such changes.

To test the correlation, we performed analysis at the country level between our economic indicators and the percentages of citizens very attached and quite attached to their country from 2000 to 2012 (see

Table 2). At first glance, the direct impacts of economic trends on identity seem to be quite limited. Only in the case of Germany is national attachment linked with economic trends in a two-fold sense, where country attachment is positively correlated with an increase in GDP_ppp and negatively related to inequality as measured by the Gini index. Therefore, these findings seem to also support H1 in general regarding the impact of the Great Recession on national identity, and H2, in particular, regarding a different impact in Germany as compared to the selected Southern European countries. In fact, only in Germany is the longitudinal correlation in aggregate terms statistically significant. A logical finding since we have established before that only in Germany is the change in national identity statistically significant (i.e., only in Germany is there enough variability in the dependent variable). Correlations were also statistically significant only for Germany when using “fairly attached” instead of “very attached”.

4.2. Individual Subjective Perceptions of the Economy

Previously, we have focused on aggregate measures at the country level, and here we analyze individual Eurobarometer data. We have selected two studies pre- and post-crisis. EB 65.2 was carried out in 2006 and contains mostly the same independent variables to be used in the analysis of EB 77.3 which was carried out in 2012.

The independent variables in our models include the evaluation by the respondent of the current situations for the national economy, European economy, personal job situation, the financial situation of their household, the employment situation of the country, and the situation of national welfare (available only for 2006 studies), as well as the expectations of the respondent for the next 12 months regarding life in general, the economic situation, the financial situation of their household, the employment situation in the country, and their expectations for their personal job situation. As regular socio-demographic controls, we have included ideology, age, education, sex, occupation, level in society, and frequency of political discussion.

Due to the distributions and statistical characteristics of our dependent variables in the different EBs, we finally opted for logistic binomial regression for analysis. Thus, our dependent variable has been recoded as a dummy variable with a value of 1 representing those very attached to their country (50% on average in the different studies and countries), while a value of 0 denotes those who feel fairly attached, not very attached, or not at all attached. Although the distribution of the variable is different across countries, we looked for a common operationalization that could suit all countries.

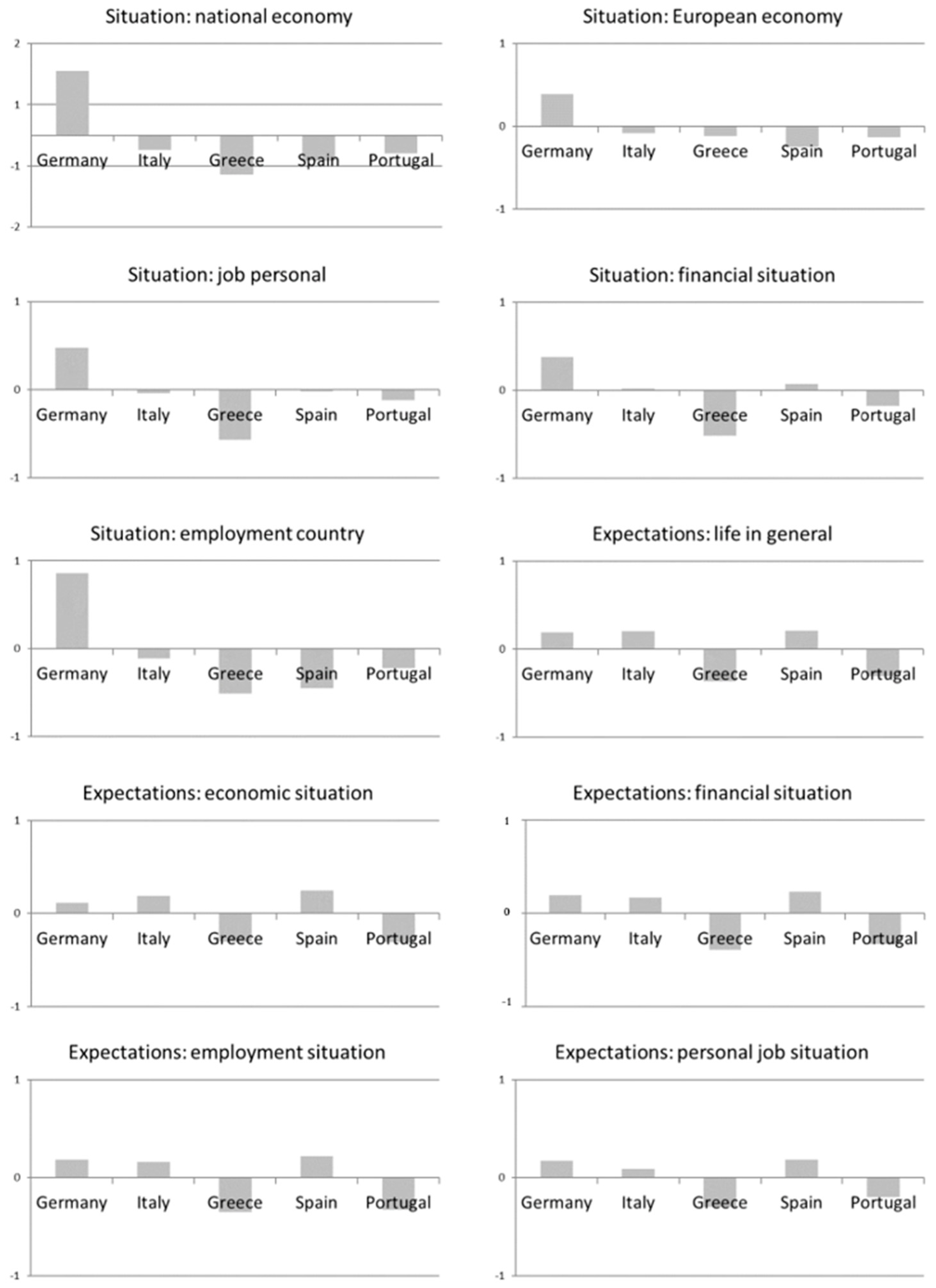

A descriptive analysis of our independent variables shows that evaluations and expectations regarding economic indicators worsened between 2006 and 2012 in general terms (

Table 3). Furthermore, it is interesting to note the changes among countries in this five-year period. In 2006, Spain was the country with consistently better evaluations and expectations, joined by Italy and Germany depending on the indicator (

Figure 5). Greece and Portugal, on the other hand, tended to share worse evaluations for economic indicators and to be less optimistic about the future. In 2012, Germany (

Figure 6) was the country with the best evaluation for all of the economic indicators included in our analysis. All selected Southern European countries shared consistently worse evaluations for any of the items. Regarding expectations for the next twelve months, Spain and Italy were more optimistic than Greece and Portugal. These two countries continued to have the worst evaluation and expectations means also in 2012. It is interesting to note that Greece and Portugal, the two countries with the worst economic evaluation and expectations, are those with the higher percentages of citizens feeling very attached to the nation. These are idiosyncratic characteristics of both countries, and therefore we focus on increasing or diminishing trends here, not differences among countries in the net percentages of attached and detached citizens. On the other extreme, Spain and Germany are the countries with the weakest national attachments in part due to the reaction against the previous monopolization of patriotism by Fracoism and Nazism, respectively (

Table 1), even if that percentage decreased after the Great Recession.

A preliminary bivariate analysis confirmed that these economic variables were correlated with the national identity indicators (

Table 4). The correlations were low and negative both in 2006 and 2012. As evaluation and expectations regarding economic indicators worsened, individual national attachment increased. These preliminary findings tend to agree with the arguments by

Brubaker (

2011) and

Andersen and Fetner (

2008) regarding the effects of relative economic deprivation on national identity. Those correlations showed no systematic changes between 2006 and 2012, although some increased and decreased from one year to the other. It is interesting to note how several factors related to the evaluation of the European economy, as well as the expectations regarding the economic and employment situation of the country, cease to be significant in 2012 for the feeling of attachment to the national group, suggesting that economic factors might play a more relevant role in positive contexts than negative contexts. This finding would be in favor of H3, suggesting that the economic variables have become less salient for national identities after the Great Recession.

Table 5 and

Table 6 present two series of logistic regression analysis for 2006 and 2012 for our five cases. In general, it can be noted that these regressions are able to explain more variance in the national identities of citizens in 2006 before the Great Recession than in 2012, which is a finding that again runs in favor of H3. Thus, the R

2 for a general regression including citizens from all five countries together drops from 0.25 (25% of explained variance on average) to 0.14. The losses of explanatory power were larger in the selected Southern European countries, whereas in Germany (where the percentage of strongly attached citizens has increased over the period), the explanatory power of regression experienced almost no change. Thus, in Germany, the explanatory power dropped by only 1% from 13% of explained variance to 12%, while for the other Southern European countries, Spain showed a change from 23% to 13%; Italy from 13% to 10%; Greece from 24% to 9%; and Portugal from 27% to 21%. In summary, our ability to understand national identities based on the economic perceptions of citizens is lower in part because of the Great Recession.

As a second observation, the importance of economic evaluations and expectations for the national identities of citizens is variable among different countries, and the relative importance does not follow the same pattern in all of them either, which could be a finding compatible with H2. In general terms, different effects can stem from the same cause (or indeed from a combination of causes) (

Mackie 1965). Effects can vary, particularly across countries, but even within a country, some people may become estranged from their national identity as a consequence of an economic crisis because they do not feel protected or taken care of, and others may present their identity as “national” to reinforce their entitlement to some particular social benefits from which they would exclude non-nationals (thus promoting welfare chauvinism). Nonetheless, we have tried to develop some predictions regarding how those effects may differ across countries in terms of H2. Neither Germany nor the selected Southern European countries among themselves were similar. This finding supports the idea that economic factors and particularly the Great Recession’s impact on national identities depend strongly on how it is understood in each country. Remember that we suggested higher percentages of change and higher importance for economic variables for Germany than the rest of the countries, taking into account the relative higher importance of cultural/achieved traits of national identity in that country as compared to the selected Southern European ones (see comments of

Figure 1).

In Germany, where the impact of the Great Recession has been lower, the percentage of citizens very attached to the nation increased by 10% on average between 2006 and 2012. At the same time, the relative importance of the economic variables included in our regression has also changed. Only two economic variables were relevant in 2006 for developing a strong attachment with the nation, and both were expressed in negative terms, i.e., a negative evaluation of the European economy and holding negative expectations regarding the financial situation of the household. In 2012, seven economic variables were statistically significant, and most of them were expressed in positive terms, namely, to hold positive expectations regarding the employment situation in the country, the personal employment situation, and the economic situation of the country; a positive evaluation of the current personal employment situation; not having a problem to pay bills; being of low social class and being a manual worker (as compared to professionals and high-ranking workers). This finding partially backs H2.

Greece experienced the worse situation among our five cases, although we are less certain about the decrease in the percentage of citizens very attached to the nation during the period of the Great Recession analyzed in this research. The relative importance of the economic variables included in our regression changed, although not in the same sense as in Germany. In this case, the relative importance of the economic variables decreased. In Greece, four economic variables were relevant in 2006 for upholding strong feelings of attachment to the nation, namely, to have negative evaluations of the employment situation in the country; to have negative expectations over life in general; to have positive expectations of the economic situation of the country; and positive evaluations of the quality of life in the country. In contrast, in 2012, only one variable remained statistically significant, namely, to uphold a negative evaluation of the employment situation in the country. Since, at the same time, Greece was closer to an ascribed understanding of identity, this finding is also consistent with H2 and H3.

These two extreme cases among our five countries seem to suggest that the economic variables are more relevant in positive economic contexts than negative ones. When the economy is perceived to be doing well (or better than neighboring economies), it serves as an anchor for developing or maintaining strong attachment to the nation, probably adding to pre-existing anchorages of national identity; however, when it is perceived to be doing poorly (or worse than neighboring economies), it loses importance and people return to different anchorages for upholding strong national identities.

Among these two extremes represented by Germany and Greece, the three remaining Southern European countries present some variability. In Spain, with the second largest loss in citizens very attached to the nation over the analyzed period, economic variables also lost importance. In Italy and Portugal, where the decreases in the percentages of citizens very attached to the nation were weaker, the relative importance of economic variables increased similarly to Germany, although more in Portugal than in Italy.

These findings offer mixed support for H2 and H3. On the one hand, the correlations found mean that we cannot rule out the hypothesis that the Great Recession has had an impact on national identities, while, on the other hand, it is not true for all cases that the roles of economic factors are more relevant after the crisis. Instead, each country seems to follow its own path regarding the importance of economic factors for upholding strong national identities. While the relative importance has increased in countries such as Germany, it has decreased in others. As suggested by H3, although it will need further research, it seems that economic factors are more relevant when an economy is performing well. In this moment, the economy will probably reinforce pre-existing national identities. During an economic crisis, most citizens will still uphold their national identities as this tends to be a stable attitude once acquired and will therefore look or return to different anchorages, forgetting, to a certain extent, about economic variables. Consistent with

Shayo (

2009), citizens would look for sources of group pride or prestige in places where they can find it, therefore paying less attention to the economy when it is performing poorly (i.e., when it will decrease a group’s prestige) than when it goes well (i.e., when it will add prestige). These differences are consistent with H2, since the extent of change and the importance of economic factors during the Great Recession were larger for Germany than for the selected Southern European countries, while at the same time, the cultural/achieved dimension of identity was also more relevant in the former and the latter (

Figure 1).