“Our Antient Friends … Are Much Reduced”: Mary and James Wright, the Hopewell Friends Meeting, and Quaker Women in the Southern Backcountry, c. 1720–c. 1790

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Literature Review

2.2. Setting

he had in those Remote Parts, for the spreading the Blessed Truth and Gospel of the Grace of God, and of our Lord Jesus Christ; and the opening Peoples Eyes and Understandings, and so turning them from Darkness unto the true Light ….

2.3. Pennsylvania and Maryland

2.4. Early Virginia Quakers

James Wright, an elder of the Hopewell Monthly Meeting, was one of the first settlers in that part of Virginia. He was a sober, honest man, grave in manners, and solid and weighty in his conversation. He was diligent in the attendance of his religious meetings, exemplary in humble waiting therein, and of a sound mind and judgment. He was cautious of giving just offense to any one, and was earnestly concerned for the unity of the brethren, and the peace of the church. ‘He appeared,’ say his friends, concerning him, ‘for some time before his last illness, as one who had finished his day’s work, and who was waiting for his change.’ He departed this life Fifth month 15th, 1759, in the 83rd year of his age.

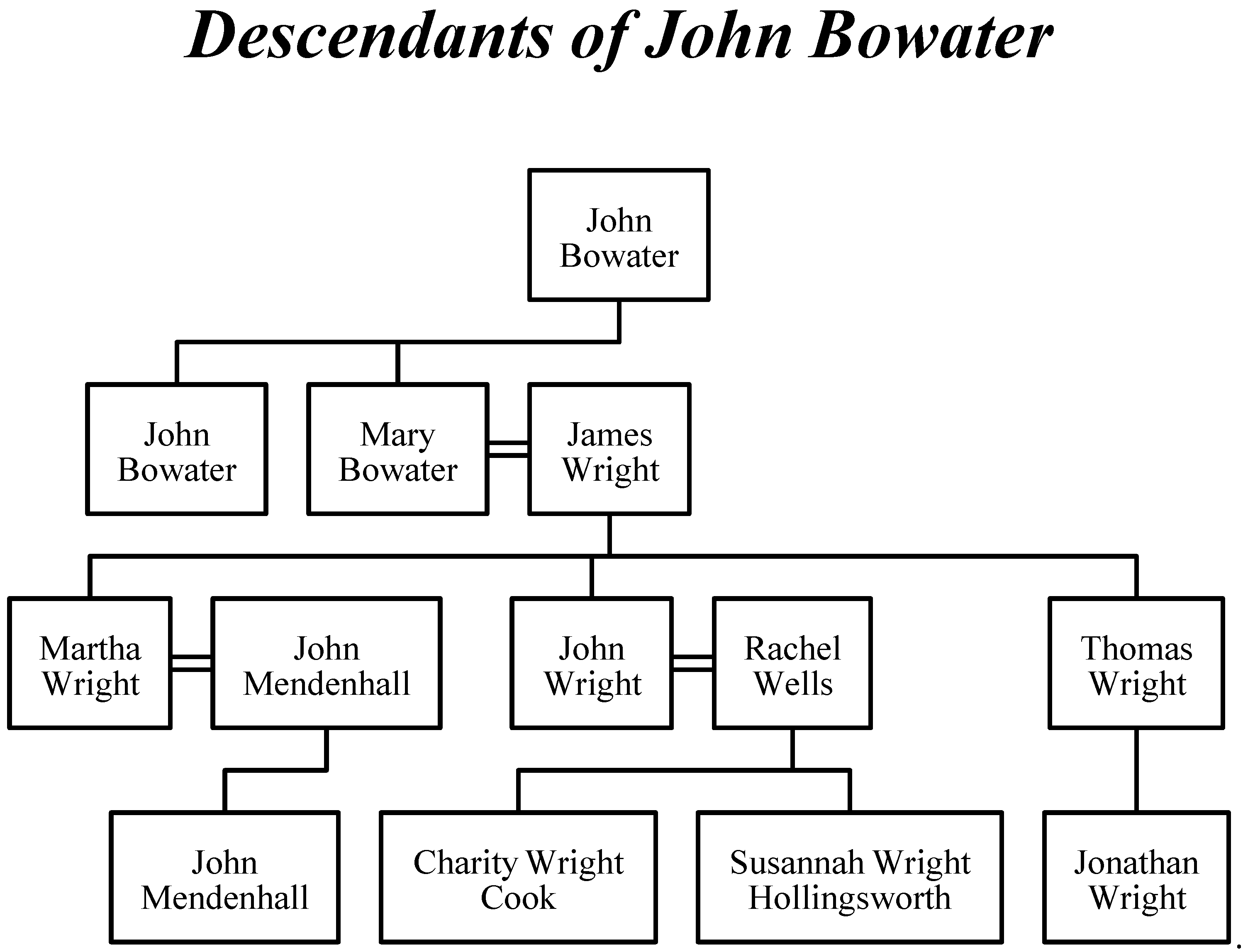

3. The Wright Connections

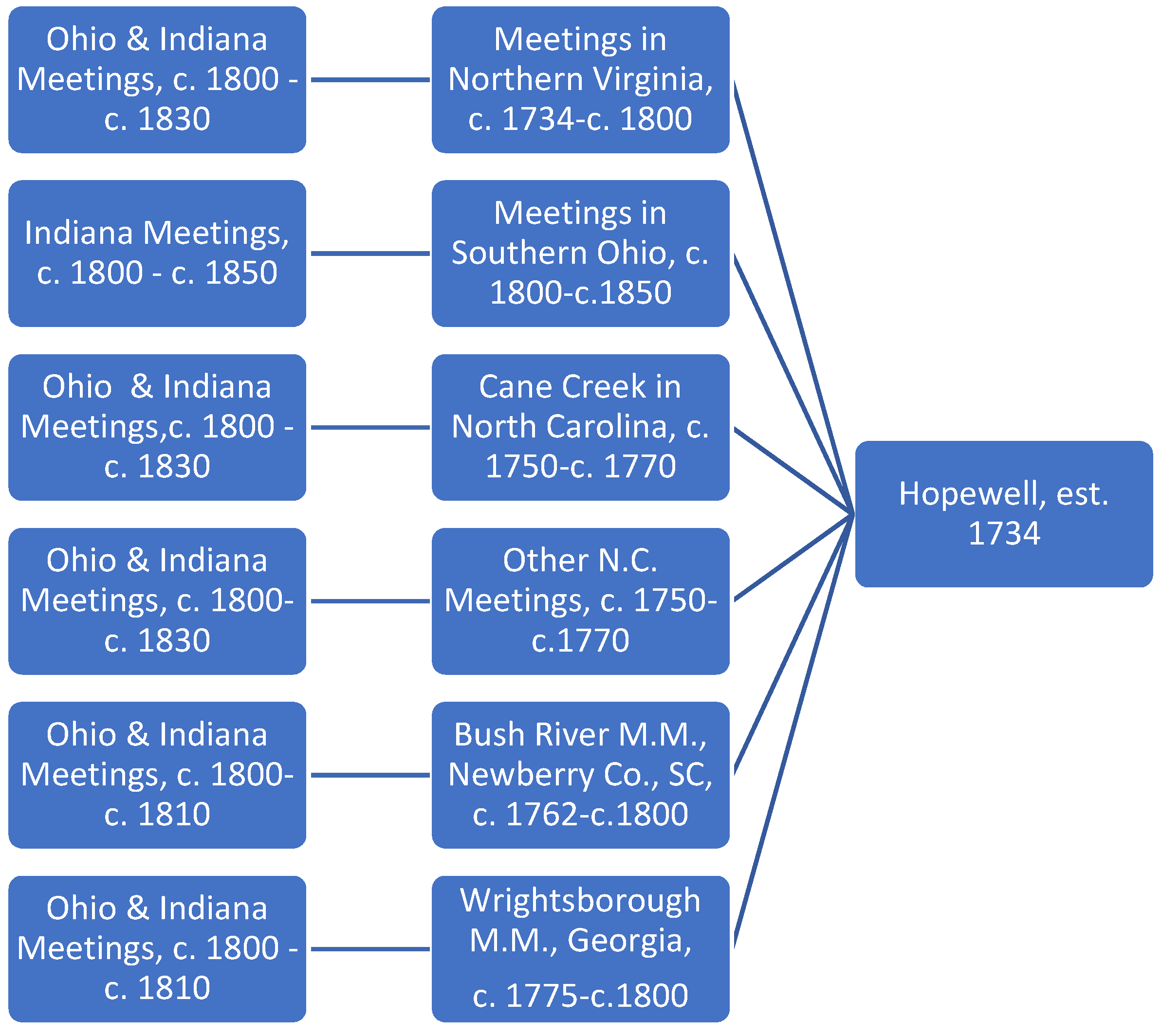

4. The Old Northwest: Ohio and Beyond

5. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

- A Salutation of Love from a Prisoner for the Testimony of Jesus Christ (1679);

- Something concerning the proceedings of Tho. Wilmate, Vicar of Bromsgrove, against him—with Salutation, &. c. (1681);

- Christian Epistles, Travels, and Sufferings of that antient Servant of Christ John Boweter (1705).

‘And this our Ancient and Faithful Brother, John Bowater, after he was concerned in a Publick Testimony in the Gospel-Ministry; he was called to Travel beyond the Seas, into America, and several Parts thereof, in the year 1677, and 1678, as New-York, Long-Island, Road-Island, New-England, New-Jersey, Maryland, Dellaware, Virginia, &c., visiting many Places and Meetings, which he had in those Remote Parts, for the spreading the Blessed Truth and Gospel of the Grace of God, and of our Lord Jesus Christ; and the opening Peoples Eyes and Understandings, and so turning them from Darkness unto the true Light; and from the Power of Satan, unto God; and for strengthening Friends in the Truth and Faith in Christ Jesus his Light and Power; and God was pleased eminently to Preserve him in his Travels, by Sea and by Land, through divers Hardships and Jeopardies, unto his safe return for England, his Native Countrey.

After which, he underwent Imprisonment in the County Goal at Worcester, and removed to the Fleet-Prison, at London, for his faithful Christian Testimony, and tender Conscience towards our Blessed Lord Jesus Christ, for non Payment of Tythes; as being perswaded the same not Payable, in this Gospel-Day, by Divine Law, but abrogated by Christ Jesus.

It appeared by the said John Bowater’s own brief Relation, that he was more kindly used by the Poor Indians in America, than by some pretended Christians here in England, after his return.

The Indians entertained him in their Wigwams (the best of their Habitations or Lodgings) but these Christians in their Cold Goals, under confinement, as they did many other of his Brethren and Friends in those times.

After his great Travels, Hardships, and Jeopardies for the Gospel’s sake, and Love to poor Souls in the American Parts of the World, in the said Years, 1677 and 1678, to be Entertained with Prisons and Confinement in England, from the year 1679, and continuing a Prisoner for Several years after, in Worcester County Goal, and to the Fleet-Prison in London, at the same Suit (as appears by his Account, and the Dates of some of his Epistles, Writ in Prison) which was but Hard Treatment, and no Christian Entertainment, by his Persecuting pretended Christians: Yet the Lord sustained him, and carried him through all his Sufferings, and much good Service, for above Twenty Years after: And when his Testimony was finished, the Lord brought him to his Peaceable and Joyful End.

God, who is no Respecter of Persons, hath been, and is pleased to make use of Poor, Low, and Mean Instruments in his Work and Service in the Gospel of his dear Son, Jesus Christ; that his Glorious Power might be manifest, and Strength made perfect in Weakness; and that out of the Mouth of Babes, he might ordain Strength, and confound the Wisdom of the World, and of all Flesh, and that no Flesh may Glory in his Prescence.

And tho’ this our Deceased Brother, was but low and poor in this World, as to external Enjoyments; yet he was rich in Faith, and in true Love: he was of an unblameable Innocent Life and Conversation; he preached well, both in Doctrine and Practice: He was found in Faith, in Charity, and Patience; and his Love sincere and constant to his Brethren, with whom he continued in true Union and sweet Communion to the End. He was a Man of Truth and Peace, and followed those things which made for Peace.

He was sound in Judgment, and in his Ministry; and sincerely preached Jesus Christ, in the simplicity of the Gospel, according to his Gift and Ability received of Christ; not in Affectation, or Emulation, or for Popularity, to gain Applause, or the Affections of the People to himself; but to the manifest in their Consciences, in the sight of God and his holy Truth, for their Conversion to the same. He did not make Merchandize of the Word of God, or his Ministry; but being low in the World, he laboured with his hands for an honest (though mean) Livelihood. He often, in tender Love and Compassion visited the Sick, with fervent Prayer and Supplication for them; being truly endued with the Spirit and Gift of Prayer, and considering his real and good Service to Truth and Friends; his being taken away, is our Loss, tho’ it his Gain.

The simplicity and plainness of his Ministry and following Epistles, do not be[--]k School-Education, but great Sincerety, Faith, Resolution, Constancy, and the Love in our Lord Jesus Christ; and not being furnished with Humane Learning, did not hinder him for being with Jesus; And therefore the following Epistles are worthy of the Serious Reading and Notice of all Friends Professing the Light, the Truth, and Faith of Christ Jesus; to whom be Glory and Dominion, for Ever and Ever.

- New York (Long Island, Gravesand, Flushing, Oyster-Bay);

- Rhode-Island;

- New-England (Sandwich, Sittuate, Boston, Salem, Duxbery, Mountinicock, Westchester upon the Main);

- New-Jersey (Shrewsberry, Burlington, Upland, Marylandside, Salem in Jarsey);

- Maryland (Delaware Town, Choptanck, Tuckahow, Kent-Island, West-Shore, Rode River, West-River, Herring-Creek, East-Shore, Kent-Island, Tuckahoe, Little Choptank, Miles River, West-River and Rudge, South-River, Herring-Creek);

- Virginia (The Clifts, Pauxon, King’s Creek, James-River in Virginia, James River, Chuckatuck, Pagan-Creek, Southward, Nansemum, Accamack, Pongaleg, by Accamack Shore, Pocamock Bay, Annamesia, Mody-Creek in Accamack, Savidge-Neck, Nesswatakes, Ocahanack, Mody-Creek, Annamessiah) (There was no clear separation between Virginia and Maryland in the narrative. Herring-Creek is in Maryland. The Clifts may refer to the land on which Clifts Plantation that was later located in Westmoreland County, and “Pauxon” may refer to Poquoson in York County. King’s Creek is also in York County. It is possible, however, that The Clifts, Pauxon, and King’s Creek refer to locations in Maryland. From “James River in Virginia”, all locations appear to have been in Virginia, with the possible exception of “Annamessiah,” which may refer to Annamessex on Maryland’s lower Eastern Shore).

| Name | Dates | Place of Death |

|---|---|---|

| Jemima Haworth Wright | 1746–1828 | Highland Co., OH |

| Jacob Pickering | 1746–1832 | Harrison Co., OH |

| Gabriel McCool | 1751–c. 1825 | Miami Co., OH |

| Mary Wright Tatcher | 1752–1836 | Highland Co., OH |

| Josiah Rogers | 1752–Aft. 1807 | Belmont Co., OH |

| James Wright | 1753–1812 | Clinton Co., OH |

| Alice Pugh | 1754–1821 | Warren Co., OH |

| Charity Wright Cook | 1755–1822 | Clinton Co., OH |

| Susannah Wright Hollingsworth | 1755–1830 | West Milton, OH |

| Sarah Haworth Wright | 1756–1831 | Clinton Co., OH |

| Elizabeth Wright McCool | 1756–c. 1825 | Miami Co., OH |

| Elizabeth Pugh Jay | 1755–1821 | Miami Co., OH |

| Thomas Wright, Jr. | 1756–1818 | Clinton Co., OH |

| Nathan Wright | 1756–Aft. 1800 | Clinton Co., OH |

| Edward Wright | 1757–1801 | Ross Co., OH |

| Ann Pugh Dillon | 1764–1842 | Tazewell Co., IL |

| Isaac Wright | 1764–1844 | Howard Co., IN |

| Rachel Pugh Jenkins | 1770–c. 1806 | Belmont Co., OH |

| Lydia Rogers Bevan | 1773–1865 | Clinton Co., OH |

References

- Allen, Richard C., and Rosemary Moore. 2018. The Quakers, 1656–1723: The Evolution of an Alternative Community. State College: Penn State Press. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, Stewart. 1997. Quaker Marriage Certificates: Using Witness Lists in Genealogical Research. The American Genealogist 72: 225–43. [Google Scholar]

- Baldwin, Stewart. 2000. John and Thomas Bowater and their sister Mary (Bowater) Wright: Early Quaker Immigrants to Pennsylvania. The American Genealogist 75: 40–46, 117–23. [Google Scholar]

- . Barbour, Hugh, and Jerry W. Frost. 1988. The Quakers. New York: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Beeman, Richard R. 1985. The Evolution of the Southern Backcountry A Case Study of Lunenburg County, Virginia, 1746–1832. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Besse, Joseph. 1753. A Collection of the Sufferings of the People Called Quakers for the Testimony of a Good Conscience from the Time of Their Being First Distinguished by That Name in the Year 1650 to the Time of the Act Commonly Called the Act of Toleration Granted to Protestant Dissenters in the First Year of the Reign of King William the Third and Queen Mary in the Year 1689. London: Luke Hinde. [Google Scholar]

- Billings, Warren M., John E. Selby, and Thad W. Tate. 1986. Colonial Virginia: A History. A History of the American Colonies. Millwood: KTO Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bowater, John. 1705. Christian Epistles Travels and Sufferings of That Ancient Servant of Christ, John Boweter; Who Departed this Life, the 16th of the 11th Month, 1704, Aged about 75 Years. London: T. Sowle. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, C. Wess, Robynne Rogers Healey, and Jon R. Kershner. 2018. Quaker Studies: An Overview: The Current State of the Field. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Dowless, Donald Vernon. 1989. The Quakers of North Carolina, 1672–1789. Ph.D. dissertation, Baylor University, Waco, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Drake, Thomas E. 1950. Quakers and Slavery in America. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dunn, Mary Maples. 1978. Saints and Sisters: Congregational and Quaker Women in the Early Colonial Period. American Quarterly 30: 582–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunn, Mary Maples. 1989. Latest Light on Women of Light. In Witness for Change: Quaker Women over Three Centuries. Edited by Elisabeth Potts Brown and Susan Mosher Stuard. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frantz, John B. 2001. The Religious Development of the Early German Settlers in ‘Greater Pennsylvania’: The Shenandoah Valley of Virginia. Pennsylvania History 68: 66–100. [Google Scholar]

- Futhey, J. Smith, and Gilbert Cope. 1881. The History of Chester County. Philadelphia: L. H. Everts. [Google Scholar]

- Glaisyer, Natasha. 2004. Networking: Trade and Exchange in the Eighteenth Century British Empire. The Historical Journal 47: 451–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Godbeer, Richard. 1992. The Devil’s Dominion: Magic and Witchcraft in Early New England. New York and Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gragg, Larry Dale. 1980. Migration in Early America: The Virginia Quaker Experience. Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press. [Google Scholar]

- Greaves, Richard L. 2001. ’Sober and Useful Inhabitants’? Changing Conceptions of the Quakers in Early Modern Britain. Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies 33: 24–50. [Google Scholar]

- Guenther, Karen. 2003. ’A Restless Desire’: Geographic Mobility and Members of the Exeter Monthly Meeting, Berks County, PA, 1710–1789. Pennsylvania History 70: 331–60. [Google Scholar]

- Gwyn, Douglas. 1995. The Covenant Crucified: Quakers and the Rise of Capitalism. Wallingford: Pendle Hill Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Heacock, Roger Lee. 1950. The Ancestors of Charles Clement Heacock: 1851–1914. Baldwin Park: Bulletin. [Google Scholar]

- Healey, Robynne Rogers. 2018. Diversity and Complexity in Quaker History. In Quaker Studies: An Overview: The Current State of the Field. Edited by C. Wess Daniels, Robynne Rogers Healey and Jon R. Kershner. Boston and Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Heinemann, Ronald L., John G. Kolp, Anthony S. Parent Jr., and William G. Shade. 2007. Old Dominion, New Commonwealth: A History of Virginia, 1607–2007. Charlottesville: University of Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- Heyrman, Christine Heyrman. 1984. Specters of Subversion, Societies of Friends: Dissent and the Devil in Colonial Essex County, Massachusetts. In Saints and Revolutionaries: Essays on Early American History. Edited by David D. Hall, John M. Murrin and Thad W. Tate. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Hinshaw, W. W. 1936–1950. Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy. Ann Arbor: Edwards Brothers, 6 vols.

- Hintz, Alex M. 1986. The Wrightsborough Quaker Town and Township in Georgia. In Quaker Records in Georgia: Wrightsborough, 1772–1793, Friendsborough, 1776–1777. Edited by R. S. Davis Jr. Roswell: W. H. Wolfe, pp. 10–14. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstra, Warren R. 2006. The planting of New Virginia: Settlement and landscape in the Shenandoah Valley. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hofstra, Warren, and Robert D. Mitchell. 1993. Town and Country in Backcountry Virginia: Winchester and the Shenandoah Valley, 1730–1800. Journal of Southern History 59: 619–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopewell Friends Committee. 1936. Hopewell Friends history, 1734–1934. Strasburg: Shenandoah Pub. House. [Google Scholar]

- Ingle, H. Larry. 1992. George Fox, Millenarian. Albion: A Quarterly Journal Concerned with British Studies 24: 261–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ingle, H. Larry. 1994. First among Friends: George Fox and the Creation of Quakerism. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Isaac, Rhys. 1982. The Transformation of Virginia: Community, Religion, and Authority, 1740–1790. Chapel Hill: Published for the Institute of Early American History and Culture, Williamsburg: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, George Lloyd, Jr. 1997. The Frontier in South Carolina: South Carolina Backcountry, 1736–1800. Westport: Greenwood Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Rufus. 1923. The Quakers in the American Colonies. London: MacMillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kerns, Wilmer L. 1995. Frederick County, Virginia: Settlement and Some First Families of Back Creek Valley, 1730–1830. Baltimore: Gateway Press. [Google Scholar]

- Kinney, Byron W. 1997. John Bowater, Early Quaker Minister. The Bromsgrove Rousler 12: 18–26. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Lawrence E. 1997. Sociability, Solitude, and Enthusiasm. Huntington Library Quarterly 60: 153–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunze, Bonnelyn Young. 1994. Margaret Fell and the Rise of Quakerism. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. [Google Scholar]

- Kunze, Bonnelyn Young. 1995. First Among Friends. The American Historical Review 100: 897–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larson, Rebecca. 1999. Daughters of Light: Quaker Women Preaching and Prophesying in the Colonies and Abroad, 1700–1775. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley, Harlow. 1923. A Century of the Indiana Yearly Meeting. Bulletin of Friends Historical Society of Philadelphia 12: 3–22. [Google Scholar]

- Lindley, Harlow. 1986. The Quaker Settlement of Ohio. In Ohio Source Records. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company, pp. 6–10. [Google Scholar]

- Lloyd, Arnold. 1950. Quaker Social History, 1669–1738, etc. [With Plates.]. London: Longman, Green, & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Mack, Phyllis. 1993. Visionary Women: Ecstatic Prophecy in Seventeenth-Century England. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mack, Phyllis. 2005. Religion, Feminism, and the Problem of Agency: Reflections on Eighteenth Century Quakerism. In Women, Gender, and the Enlightenment. Edited by Sarah Knott and Barbara Taylor. London: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 434–60. [Google Scholar]

- McCormick, JoAnne. 1984. The Quakers of Colonial South Carolina, 1670–1807. Ph.D. dissertation, University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Middleton, Richard. 2007. Colonial America: A History, 1565–1776. Malden: Blackwell. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Robert D. 1977. Commercialism and Frontier: Perspectives on the Early Shenandoah Valley. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia. [Google Scholar]

- O’Dell, Cecil. 1995. Pioneers of Old Frederick Co., VA. Marceline: Walsworth Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- O’Neall, John Belton. 1892. The annals of Newberry: In 2 Parts. Newberry: Aull and Houseal. [Google Scholar]

- Opper, Peter Kent. 1975. North Carolina Quakers: Reluctant Slaveholders. The North Carolina Historical Review 52: 37–58. [Google Scholar]

- Pestana, Carla Gardina. 1991. Quakers and Baptists in Colonial Massachusetts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pestana, Carla Gardina. 1993. The Quaker Executions as Myth and History. Journal of American History 80: 441–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Plank, Geoffrey. 2012. John Woolman’s Path to the Peaceable Kingdom: A Quaker in the British Empire. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Risjord, Norman. 2001. Representative Americans: The Colonists, 2nd ed. Lanham: Rowman and Littlefield, Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Ross, Isabel. 1949. Margaret Fell, Mother of Quakerism. London: Longmans, Green. [Google Scholar]

- Routh, Martha. 1822. Memoir of the Life, Travels, and Religious Experience of Martha Routh, Written by Herself, or Compiled from Her Own Narrative. York: Alexander. [Google Scholar]

- Rutman, Darrett, and Anita H. Rutman. 1984. A Place in Time: Middlesex Co., VA, 1650–1750. New York: Norton. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, George. 1862. History of Delaware County, Pennsylvania. Philadelphia: H. B. Ashmead. [Google Scholar]

- Sugrue, Thomas J. 1992. The Peopling and Depeopling of Early Pennsylvania: Indians and Colonists, 1680–1720. The Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 116: 3–31. [Google Scholar]

- The Friend. 1859. Biographical Sketches of Ministers and Elders and other concerned members of the yearly meeting of Philadelphia. The Friend 9: 413. [Google Scholar]

- Tolles, Frederick B. 1948. Meeting House and Counting House: The Quaker Merchants of Colonial Philadelphia, 1682–1763. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tolles, Frederick B. 1953. Quaker History Enters Its Fourth Century. William and Mary Quarterly 3rd Series 10: 247–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tracey, Grace L., and John P. Dern. 1987. Pioneers of Old Monocacy: The Early Settlement of Frederick Co., MD, 1721–1743. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company. [Google Scholar]

- Troxler, Carole Watterson. 2011. Farming Dissenters: The Regulator Movement in Piedmont North Carolina; Raleigh: Office of Archives and History, North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources.

- Weeks, Stephen B. 1896. Southern Quakers and Slavery: A Study in Institutional History. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, Robert V. 1972. Quaker Marriage Patterns in Colonial Perspective. William and Mary Quarterly 3rd Series 29: 415–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whiting, John. 1708. A Catalogue of Friends Books; Written by Many of the People, Called Quakers, from the Beginning or First Appearance of the Said People. London: J. Sowle. [Google Scholar]

- Wulf, Karin. 2000. Not All Wives: Women of Colonial Philadelphia. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Knight, T.D. “Our Antient Friends … Are Much Reduced”: Mary and James Wright, the Hopewell Friends Meeting, and Quaker Women in the Southern Backcountry, c. 1720–c. 1790. Genealogy 2021, 5, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5030072

Knight TD. “Our Antient Friends … Are Much Reduced”: Mary and James Wright, the Hopewell Friends Meeting, and Quaker Women in the Southern Backcountry, c. 1720–c. 1790. Genealogy. 2021; 5(3):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5030072

Chicago/Turabian StyleKnight, Thomas Daniel. 2021. "“Our Antient Friends … Are Much Reduced”: Mary and James Wright, the Hopewell Friends Meeting, and Quaker Women in the Southern Backcountry, c. 1720–c. 1790" Genealogy 5, no. 3: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5030072

APA StyleKnight, T. D. (2021). “Our Antient Friends … Are Much Reduced”: Mary and James Wright, the Hopewell Friends Meeting, and Quaker Women in the Southern Backcountry, c. 1720–c. 1790. Genealogy, 5(3), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy5030072