The Racial and Ethnic Identity Development Process for Adult Colombian Adoptees

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

2.2. Participants

2.3. Data Collection Methods

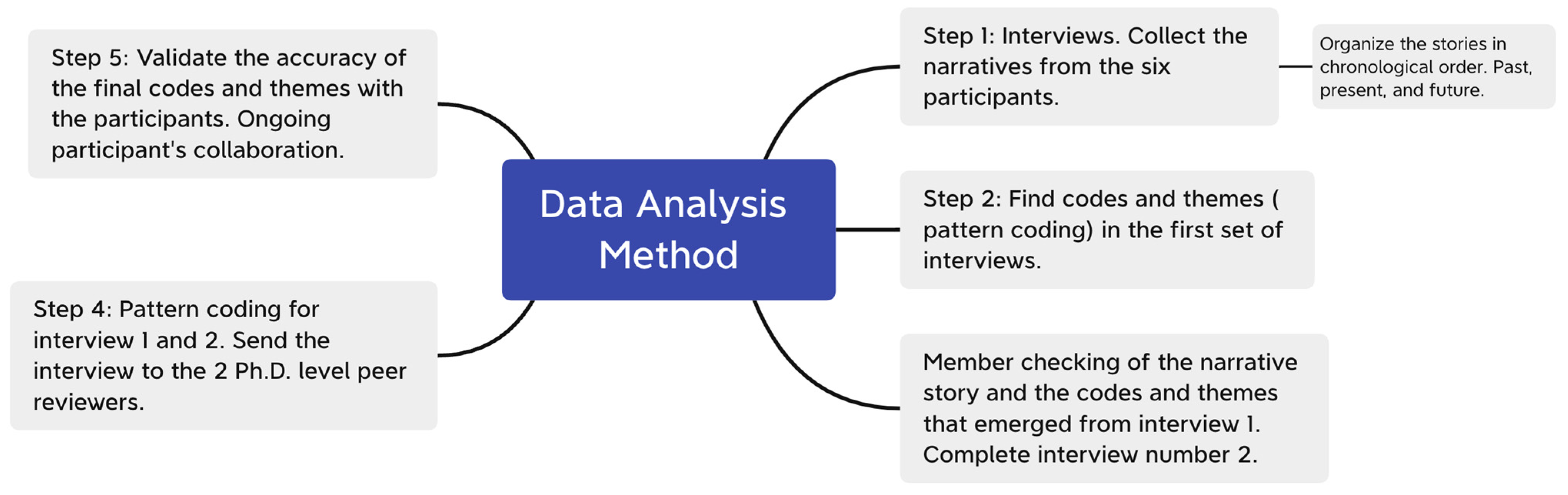

2.4. Data Analysis Process

2.5. Measures for Ensuring Trustworthiness

3. Colombian Adoptees and Their Racial and Ethnic Identity Process

3.1. Putting the Puzzle Together: “It Is a Dynamic Process”

I think when I was a little kid, I really couldn’t talk about anything and was very shut off about being Colombian, obviously, I knew that, but I didn’t really wanna talk about race … I think it’s changed a lot since I was a kid versus now.

3.2. Brown on the Outside, White on the Inside

3.2.1. “I Am Not White”

3.2.2. Racism

For the longest time, I really didn’t identify myself as a person of color because I felt like I had grown up into a such a Caucasian household, but as I grew older into adulthood and I started talking to other people of color, I realized that I guess I was technically a person of color, I wasn’t considered to be someone of African-American descent or any of that, but I realized I was a minority and I maybe didn’t have it as rough as other people of color might have, but I still was facing discrimination.

Well, like with ethnicity, I felt I had it because I felt like when I was around a lot of Colombians, that I wasn’t really Colombian enough. I noticed that one day we were invited, my husband and I were invited to a dinner from a friend of mine up in Fargo, and she was from, I believe, Bogota, and she knew a bunch of people here that were also Colombian. And so she invited me over there and I was looking forward to it, but then when I got there, I just felt this immediate disconnect because everyone there assumed that I spoke Spanish and when they found out that I didn’t speak Spanish, they didn’t wanna speak to me anymore.

And then also Colombian immigrants here in the Seattle area who [chuckle] who would claim that because I didn’t speak Spanish and that because I wasn’t raised in Colombia, that I had no right trying to call myself Colombian, trying to wear “la camiseta” [Colombian’s soccer team shirt] during games. Right? Like, “Who do you think you are, you a nerd? You’ve never lived in Columbia, you weren’t raised there, you don’t speak Spanish”. “No tienes derecho”. It’s what they would always say. And it wasn’t happening all the time, only when I would go to like a de julio celebration here or like a … Yeah, a soccer game, and I would come with my jersey on or something and … Or with a flag or something [chuckle] And sometimes people would say, “Oh yeah”. And they started speaking to me in Spanish, and it’s like, “Oh no, sorry. Lo siento. I don’t speak Spanish”. Yeah, yeah. And the response was, many times, “Oh, then, what are you doing here? You’re not really Colombian. You’re not Colombian enough”.

3.2.3. Racial Isolation

3.3. A Chamaleon with Imposter Syndrome

Now I’m kind of fluctuating between all three, but lately, I’ve been using the Indigenous one, the Native-American sort of one. So, I almost get to pick and choose, daily, which one I want to be, which is in its own way nice and at the same time it’s, again, no less confusing. So, it went back and forth. It did, but it always changed, it kinda would change to suit the situation. After 10 years old, it just started going back and forth, like a tennis match.

In terms of race, I would say I have Indigenous ancestry and Spanish, so White-European, so a mix of those two. And I typically have a lot of issues with the way the US census puts race down. I always have a lot of issues with that because if I say I’m Native American, they’re gonna think I’m from one of the tribal nations in the United States, but we all know that in the Americas, there’s multiple Indigenous groups, and then if I put … I don’t identify as Caucasian, so yeah, so I guess it’s like how I’d say race.

3.4. Adoption as a Loss

3.4.1. Unethical Adoptions

Well, there’s two versions, there’s the version that’s in the adoption documents and then there’s the version that she told me, and they are opposite. The version that she told me was that that’s not true, that she never gave me up for adoption. She wanted to send me to live with her sisters and her mother in Tumaco like she did with my brother, but then she said that social workers took me and then promised her that she could go back and get me after a few days after she healed ‘because I was a C-section baby. And she went back and then I was gone by that point. My bio mom said, well, there’s nothing I could do. And I didn’t have money to pay a lawyer to fight the case and so I just hoped for the best.

Please let’s not do that anymore, especially knowing what actually happened to my original mother, where she was forced to give me up or give up all her kids, I can’t see it as anything that is remotely a good thing, at least in that standard sense. The fact that my mother was forced to give me up for adoption because her first husband disappeared in the military, and she was receiving widowed benefits. She had three kids with him, she met someone else, he got her pregnant, and then when he found out, he left. She was told by the government and the military that, “If you don’t give up this new kid who’s out of wedlock, you’ll lose your widow benefits and you’ll have to also sacrifice your other three kids, all of them will go into child services”. She was also promised apparently, “Okay, so we won’t put him up for adoption entirely, he’ll go with a sponsor family and after a certain period of time, you can get him back”. She was also promised that. She changed her mind after I was … Immediately after I was taken out of her arms that first night, she changed her mind, she wanted to actually get me back, she would go back to the orphanage every single day, but they said, “No, you signed over your parental rights, he’s no longer yours”. Everyone in the organization seems okay at first, once we got back into United States, once they had me, they kept on wanting my adoptive parents to be a part of the organization, from what I was told, almost as a mascot, they wanted people to … They wanted them to say what a great story it was and how the process went so smoothly so they can get other people to continuously just try and adopt. It did take them a long time looking at my records to figure out what happened because it seemingly was written, handwritten, my number … It certainly was forged, so that happened with me, too. Yeah, so I can definitely see where the corruption is, or was at least between those couple of decades rampant in the country.

And from what we were told by our siblings was that my older brother was in charge of watching me and someone had a problem with my mother and called the welfare and they took us. And when they took us, because my mom was uneducated and didn’t have any resources or any help, she tried to take us back and they said that they took her rights away and they put us in the system, and we were adopted out. Catholic orphanages were falsifying their documents stating that their children were also abandoned, and they were giving them false cedula numbers, they were putting false names on the documents of who their so-called parents were, and so that’s why they were having a hard time finding their parents. There was a lot of confusion in it. My parents said in the papers they read us that my brother and I were living on the streets for about a year and then we got picked up and put into foster care. And we learned recently that a lot of the information was just stuff that was put in there because they needed to put information in. And I learned from a lot of adoptees that the term abandonment was used in many documents.

3.4.2. Ethical Adoptions

3.4.3. Internalized Symptoms

Only this past year have I been able to come to terms with why I have always felt … I’ve had depression since I was 10, literally, that’s not a hyperbolic. I’ve had depression that long, where I’ve always felt unloved, unlovable, and only now, recently in the past year, since my birth family came back into the picture, have I been able to, as a phrase goes, come out of the fog and understand why maybe I really genuinely felt like that, and it really just might be adoption, it might just be being adopted.

But the therapist that I saw when I was younger, it was more to deal with my depression. It wasn’t until I was older that I realized, this is why I need to see a therapist, because I have identity issues and I need to find out, what is the root to all of this pain that I’m having and this depression and why am I always being put into a depression? I don’t know if it made me an emotional eater. I was having a lot of anger and meltdowns and I didn’t know why.

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Adoption Network. 2022. Brief History of Adoption in the United States|Adoption Network. September 24. Available online: https://adoptionnetwork.com/history-of-adoption/ (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Alayon, Patrick. 2014. “Colombia’s Recent Accession to the Hague Convention on Service Abroad”. University of Miami School of Law. Inter-American Law Review. March 24. Available online: https://inter-american-law-review.law.miami.edu/colombias-accession-hague-convention-service/ (accessed on 18 April 2023).

- Baden, Amanda L. 2016. ‘Do You Know Your Real Parents?’ And Other Adoption Microaggressions. Adoption Quarterly 19: 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, Amanda L., and Robbie Steward, eds. 2007. The Cultural-Racial Identity Model. In Handbook of Adoption: Implications for Researchers, Practitioners, and Families. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Baden, Amanda L., Judith L. Gibbons, Samantha L. Wilson, and Hollee McGinnis. 2013. International Adoption: Counseling and the Adoption Triad. Adoption Quarterly 16: 218–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baden, Amanda L., Lisa M. Treweeke, and Muninder K. Ahluwalia. 2012. Reclaiming Culture: Reculturation of Transracial and International Adoptees. Journal of Counseling & Development 90: 387–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bautista-Lopez, Omaira. 2016. Regimen Juridico de la Adopcion Internacional: Un Estudio Sobre Politicas de Prevencion y Proteccion al Menor Adoptado por Extranjeros. Ph.D. dissertation, Universidad Catolica de Colombia, Bogota, Colombia. Available online: https://repository.ucatolica.edu.co/server/api/core/bitstreams/27bbf648-1efc-4ea8-89ed-b39c2b213e0c/content (accessed on 20 May 2022).

- Bloomberg, Linda Dale, and Marie Volpe. 2012. Completing Your Qualitative Dissertation: A Road Map from Beginning to End, 2nd ed. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Branco-Alvarado, Susan, Joy Rho, and Simone Lambert. 2014. Counseling Families with Emerging Adult Transracial and International Adoptees. The Family Journal 22: 402–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, Susan F. 2021. The Colombian Adoption House: A Case Study. Adoption Quarterly 24: 25–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, Susan F., and Veronica Cloonan. 2022. False Narratives: Illicit Practices in Colombian Transnational Adoption. Genealogy 6: 80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Branco, Susan F., Sanna Stella, and Amelia Langkusch. 2022. The Reclamation of Self: Kinship and Identity in Transnational Colombian Adoptee First Family Reunions. The Family Journal 30: 106648072211041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brodzinsky, David, Megan Gunnar, and Jesus Palacios. 2022. Adoption and Trauma: Risks, Recovery, and the Lived Experience of Adoption. Child Abuse & Neglect 130: 105309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brookover, Dana (Host). 2023. Dissertation Nation: Episode 6: Dr. Veronica “Vero” Cloonan on Apple Podcasts. Available online: https://podcasts.apple.com/us/podcast/episode-6-dr-veronica-vero-cloonan/id1636592108?i=1000592185128 (accessed on 6 March 2023).

- Butina, Michelle. 2015. A Narrative Approach to Qualitative Inquiry. American Society for Clinical Laboratory Science 28: 190–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carreazo, Diana I. 2016. Morir sin saber un origen: La realidad de miles de adoptados Colombianos. Vice News. October 16. Available online: https://www.vice.com/es/article/ppnbz9/morir-sin-saber-un-origen-la-realidad-de-miles-de-adoptados-colombianos (accessed on 7 March 2023).

- Cheney, Kristen E. 2014. ‘Giving Children a Better Life?’ Reconsidering Social Reproduction, Humanitarianism and Development in Intercountry Adoption. The European Journal of Development Research 26: 247–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheney, Kristen E. 2021. Closing New Loopholes: Protecting Children in Uganda’s International Adoption Practices. Childhood 28: 555–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cloonan, Veronica. 2022. The Racial and Ethnic Identity of Adult Colombian Adoptees. Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of the Cumberlands, Williamsburg, KY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Cloonan, Veronica, Susan Branco, Tammy Hatfield, and LaShauna Dean. 2023. The Racial and Ethnic Identity Model for Adult Colombian Adoptees. Unpublished manuscript. [Google Scholar]

- Dekker, Marielle C., Wendy Tieman, Anneke G. Vinke, Jan van der Ende, Frank C. Verhulst, and Femmie Juffer. 2017. Mental Health Problems of Dutch Young Adult Domestic Adoptees Compared to Non-Adopted Peers and International Adoptees. International Social Work 60: 1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fisher, Celia B., and Richard M. Lerner. 2005. Encyclopedia of Applied Developmental Science. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications, vol. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Flores-Koulish, Stephanie, and Susan Branco Alvarado. 2015. Navigating Both/and: Exploring the Complex Identity of Latino/a Adoptees. Journal of Social Distress and the Homeless 24: 61–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallegos, Placida V., and Bernardo M. Ferdman. 2012. Latina and Latino Ethnoracial Identity Orientations: A Dynamic and Developmental Perspective. In New Perspectives on Racial Identity Development: Integrating Emerging Frameworks, 2nd ed. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Helms, Janet E., dir. 2008. A Race Is a Nice Thing to Have. Alexandria: Microtraining Associates. Available online: https://video.alexanderstreet.com/watch/a-race-is-a-nice-thing-to-have (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Instituto Colombiano de Bienestar Familiar (ICBF). 2022. Estadísticas del Programa de Adopciones. February 6. Available online: https://www.icbf.gov.co/estadisticas-del-programa-de-adopciones-31122020 (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Javier, Rafael Art, ed. 2007. Handbook of Adoption: Implications for Researchers, Practitioners, and Families. Thousand Oaks: SAGE Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Kawan-Hemler, Collin. 2022. From Orphan, to Citizen, to Transnational Adoptee: The Origins of the US-Colombian Adoption Industry and the Emergence of Adoptee Counternarratives. Unpublished thesis. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Grace S., Karen L. Suyemoto, and Castellano B. Turner. 2010. Sense of Belonging, Sense of Exclusion, and Racial and Ethnic Identities in Korean Transracial Adoptees. Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology 16: 179–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, Jeong-Hee. 2016. Understanding Narrative Inquiry: The Crafting and Analysis of Stories as Research. Los Angeles: SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Lamanna, Mary Ann, Agnes Riedmann, and Susan D. Stewart. 2018. Marriages, Families and Relationships: Making Choices in a Diverse Society, 13th ed. Stamford: Cengage Learning. [Google Scholar]

- Lieblich, Amia, Rivka Tuval-Mashiach, and Tamar Zilber. 1998. Narrative Research: Reading, Analysis and Interpretation. Applied Social Research Methods Series; Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications, vol. 47. [Google Scholar]

- Mahmood, Samina, and John Visser. 2015. Adopted Children: A Question of Identity: To Come. Support for Learning 30: 268–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounts, Brandy, and Loretta Bradley. 2020. Issues Involving International Adoption. The Family Journal 28: 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park-Taylor, Jennie, and Hannah M. Wing. 2019. Microfictions and Microaggressions: Counselors’ Work With Transracial Adoptees in Schools. Professional School Counseling 23: 2156759X20927416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phinney, Jean S. 1990. Ethnic Identity in Adolescents and Adults: Review of Research. Psychological Bulletin 108: 499–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roszia, Sharon Kaplan, and Allison Davis Maxon. 2019. Seven Core Issues in Adoption and Permanency: A Comprehensive Guide to Promoting Understanding and Healing in Adoption, Foster Care, Kinship Families and Third Party Reproduction. The Science of Parenting Adopted Children. London and Philadelphia: Jessica Kingsley Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Samuels, Gina Miranda. 2009. “Being Raised by White People”: Navigating Racial Difference among Adopted Multiracial Adults. Journal of Marriage and Family 71: 80–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- San Román, Beatriz. 2021. ‘I Prefer Not to Know’: Spain’s Management of Transnational Adoption Demand and Signs of Corruption. Childhood 28: 492–508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smolin, David M. 2004. Intercountry Adoption as Child Trafficking. Valparaiso University Law Review 39: 281–325. [Google Scholar]

- Smolin, David M. 2010. Child Laundering and the Hague Convention on Intercountry Adoption: The Future and Past of Intercountry Adoption. University of Louisville Law Review 48: 441–98. [Google Scholar]

- Smolin, David M. 2021. The Case for Moratoria on Intercountry Adoption. Southern California Interdisciplinary Law Journal 30: 501. [Google Scholar]

- Sohn, Stephen Hong. 2022. “This Is Cousinland”: The Korean War, Post-Armistice Poetics, and Reparative Aesthetics in Julayne Lee’s Not My White Savior. Adoption & Culture 10: 22–42, 161–62. [Google Scholar]

- The Hague Convention. n.d. HCCH|Colombia Joins the Hague Evidence Convention. Available online: https://www.hcch.net/en/news-archive/details/?varevent=242 (accessed on 26 April 2023).

- The United States (U.S.) Department of Justice. 2020. Three Individuals Charged with Arranging Adoptions from Uganda and Poland through Bribery and Fraud. Available online: https://www.justice.gov/opa/pr/three-individuals-charged-arranging-adoptions-uganda-and-poland-through-bribery-and-fraud (accessed on 17 August 2020).

- The United States (U.S.) Department of State. 2022. Annual Reports. Intercountry Adoption. Available online: https://travel.state.gov/content/travel/en/Intercountry-Adoption/adopt_ref/AnnualReports.html (accessed on 19 April 2023).

- Villa Guardiola, Vera Judith, Ángela Patricia Gallego Betancur, and José Antonio Soto Sotelo. 2022. La Adopción Por Familias Monoparentales En Las Legislaciones de Colombia y Mexico. Advocatus 19: 177–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterman, Jill, Audra K. Langley, Jeanne Miranda, and Debbie B. Riley. 2018. Overview of Adoption-Specific Therapy. In Adoption-Specific Therapy: A Guide to Helping Adopted Children and Their Families Thrive. Edited by Jill Waterman, Audra K. Langley, Jeanne Miranda and Debbie B. Riley. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association, pp. 27–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Participant 1 | Place of Birth | Age of Adoption | Adoptive Parents’ Race | Place Where They Grew Up | Age |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gonzalo | Bogota | 5 months | White | Midwest, USA | 33 |

| Andres | Cali | 7 months | White | West Coast, USA | 37 |

| Valentino | Bogota | 5.5 months | White | East Coast, USA | 34 |

| Juliana | Bogota | 4 months | White | East Coast, USA | 36 |

| Camila | Bogota | 4 months | White | East Coast, USA | 28 |

| Carmen | La Mesa | 6 years | White | Midwest, USA | 36 |

| Themes | Definition | Participants 1 Who Endorsed It |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1: Putting the puzzle together. “It is a Dynamic Process”. | When racial and ethnic identity changes throughout the years. | Camila, Juliana, Andres, and Valentino. |

| Theme 2: Brown on the outside, White on the inside. | When participants grew up in a White family, but they do not look like they are White. | Camila, Juliana, Valentino, Gonzalo, and Carmen. |

| Theme 3: A chameleon with imposter Syndrome. | When the participant can adapt to the Colombian and White environment without feeling like they fully fit in either of these spaces. | Andres, Gonzalo, Valentino, and Juliana. |

| Theme 4: Adoption as a loss. | When adoption is experienced as a loss or as a traumatic experience. | Camila, Valentino, Carmen, Andres, Juliana, Gonzalo. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Cloonan, V.; Hatfield, T.; Branco, S.; Dean, L. The Racial and Ethnic Identity Development Process for Adult Colombian Adoptees. Genealogy 2023, 7, 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7020035

Cloonan V, Hatfield T, Branco S, Dean L. The Racial and Ethnic Identity Development Process for Adult Colombian Adoptees. Genealogy. 2023; 7(2):35. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7020035

Chicago/Turabian StyleCloonan, Veronica, Tammy Hatfield, Susan Branco, and LaShauna Dean. 2023. "The Racial and Ethnic Identity Development Process for Adult Colombian Adoptees" Genealogy 7, no. 2: 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7020035

APA StyleCloonan, V., Hatfield, T., Branco, S., & Dean, L. (2023). The Racial and Ethnic Identity Development Process for Adult Colombian Adoptees. Genealogy, 7(2), 35. https://doi.org/10.3390/genealogy7020035