[The thick photograph album’s] favoured location was … on pier or pedestal tables in the drawing-room. Leatherbound, embossed with metal mounts, it sported upon its gold-rimmed, fingerthick pages absurdly draped or laced figures—Uncle Alex and Aunt Riekchen, Trudchen when she was little …. (

Benjamin [1931] 2011, p. 18)

As Walter Benjamin informed us, the heavy album on display in his family’s elegant drawing room in nineteenth-century Berlin contained photographic portraits of family members. Unfortunately, its fate is unknown. This album, and those of many other bourgeois Jews of the same era, contained collections of stylized studio photographs taken during the craze for photographic self-portraits that began among the bourgeoisie in the 1850s and continued, worldwide, well after the invention of Kodak’s portable box cameras in 1888. The collection of portraits between the album’s covers, a visual archive, was a product of the photo-sharing visual culture of the period.

Relatively few of these Jewish family heirlooms survived the twentieth century, compared with those that belonged to non-Jews. Well-off Jews in the Russian Empire lost their possessions during the Russian Revolution, including their family albums. During World War II (WWII), the Nazis looted or destroyed albums that belonged to Jews whom they deported and/or murdered. Nevertheless, some one hundred nineteenth-century Jewish portrait albums are now preserved in at least 24 different museums, archives, and libraries worldwide. It is not known how many remain in private hands. Made by Jews in the British, German, Austro-Hungarian, Russian, and Ottoman Empires, as well as in France, Italy, the Low Countries, and Scandinavia’s cities, these heritage objects invite us to discover and reconstruct the memories of long-forgotten ancestors.

This article argues that the earliest genre of the family photograph album may catalyze the construction or expansion of a family’s genealogy, embody a visual genealogy of extended families, and/or reveal genealogical memories of family migration or dispersion. Jews left photographs and portrait albums, just as they left headstones in graveyards, for us to visit, study, and discuss when they were gone. After outlining the methodology used, this essay presents case studies in which genealogical discoveries, visual genealogies, and memories of family dispersion are extracted from such albums. Finally, the discussion looks at the role of family albums in the passing down of family history to future generations.

1. Introduction

The portrait-card albums created by bourgeois Jews in the nineteenth century contain mini-archives that may be of interest to genealogists. As Susan Sontag famously noted, “Those ghostly traces, photographs, supply the token presence of the dispersed relatives. A family’s photograph album is generally about the extended family—and, often, is all that remains of it.” (

Sontag [1973] 1977, pp. 8–9). Such albums embody “genealogical memory”, which the anthropologist Gaynor Macdonald defined as “the memory of real people in real time.” (

Macdonald 2003, p. 232).

Nineteenth-century Jews and non-Jews used their portrait albums as mnemonics. Stories told about relatives who featured in an album transmitted both genealogy and family history. As Anna Dahlgren noted, such books “were conversation pieces that functioned better without text, as the images could prompt social contact in the form of inquiries and discussion” (

Dahlgren 2010, p. 175). For this reason, album makers did not write the names of the subjects on the album’s pages. The “show and tell” function of these books disappeared when albums were given away to institutions. Martha Langford observed that the deposition of an album in a museum “suspends its sustaining conversation, stripping the album of its social function and meaning” (

Langford 2008, p. 5). For many families that owned albums, the destruction of the Holocaust cut off the communication of family history prematurely. The oral communication of family memories around historical albums that were not impacted by war eventually ceased with time; Jan Assmann found that the transmission of family memories lasts, at best, only three generations (

Assmann 1995, p. 127). Most of the private owners of a nineteenth-century family album today no longer know the names of unlabeled portraits. Such memory loss challenges the genealogical use of historic albums today. Luckily, sometimes, a person who inherited an album, aware that its genealogical information was rapidly fading, noted on its cardboard pages the names of the people whom they could recognize therein and, occasionally, dates as well. These inscriptions are vital for genealogists.

The collection of photographic portraits began in France in the 1850s among the elites and the middle classes and quickly spread across the globe. In 1854, the Frenchman A. A. E. Disdéri invented a technology to make multiple prints from a single photographic plate. He stuck his albumen prints on small cards the size of a visiting card, a carte de visite (ca. 11.4 cm × 6.3 cm). Other photographers soon embraced this technology, and millions of people, including Jews, flocked to photographers’ studios to acquire such newly affordable self-portraits (

McCauley 1985). If they were satisfied that these showed them at their best, they gifted and exchanged them with family and friends. Disdéri’s photographic process significantly cut the cost of portraiture and revolutionized visual culture. It generated a veritable mania for creating and collecting these small images, which the Parisian journalist Victor Fournel named, in 1858, “

portraituromanie” (cited in

Charpy 2007, p. 148), recently termed “cartomania” by English-speaking researchers (e.g.,

Cosens 2003, pp. 34–35;

Rudd 2016, pp. 196–97).

In 1861,

The Photographic News predicted that the family portrait album, “an illustrated book of genealogy,” would “supersede the first leaf of the family Bible,” which often contained lists of the births and deaths in the owner’s family (

Carte de Visite Portraits 1861, p. 342). However, most albums do not contain such information and did not serve Jews as birth and

yahrzeit registers. (

Yahrzeit is the Yiddish term for the anniversary of a death.) In the late 1850s and early 1860s, newly designed albums that resembled Christian liturgical books enabled the exhibition of personal photographic collections of portraits to guests in the home (see

Figure 1). As Benjamin noted, these books were expensively bound and had thick, gilt-edged cardboard pages with pre-cut apertures the size of the photographic cards. Each page framed one, two, or more portraits, depending on the number of apertures provided. Portraits could be removed from their frames on the album’s page, given away, and replaced. The binding of the album, as well as the rich clothing seen in the portraits, conveyed class.

Jewish and non-Jewish men and women often collected and displayed photographic images of friends, casual acquaintances, and famous people they admired, in addition to portraits of their relatives. Photographic and art historians around the world have studied these nineteenth-century portrait albums from various perspectives. For example, Elizabeth Siegel studied the social uses of portrait albums in the nineteenth-century USA; she wrote that “the album was seen to be filled as much by the desire to construct a family tree as by the urge to acquire portraits in great numbers” (

Siegel 2010, p. 125). Patrizia di Bello examined gender issues in four albums created by British women (

Di Bello 2007);

Martha Langford (

2008) focused on the albums’ orality in her study of such books in the McCord Museum of Canadian History. Jill Haley’s doctoral thesis surveyed evidence of colonialism in the albums of nineteenth-century immigrants to Otago, New Zealand (

Haley 2017). Cultural anthropologist Elizabeth Edwards similarly stressed the importance of “show and tell” when looking for meaning in historical albums (

Edwards 1999, p. 230;

2005, p. 35).

Earnestine Jenkins (

2020) argued that an album assembled by a woman of mixed race in Memphis fashions a legacy of status and shared identity, which she, her family, and mixed-race friends could not previously claim in the urban South prior to the reconstruction. As each album is a unique visual archive that embodies the maker’s social world,

Annie Rudd (

2016) and

Stephen Burstow (

2016) compared the nineteenth-century photo-sharing visual culture with social media in the digital age. None of these considered the vintage albums as a primary source for genealogists.

Photographs have nevertheless long served as a focus for discussing collective family memories. Anthropologists Roslyn Poignant and

Gaynor Macdonald (

2003, pp. 235–36) have used collections of photographs of native Australian peoples with fractured histories to facilitate the telling of genealogies, establish family continuities, and revive genealogical memory.

Poignant (

1992, p. 74) observed that the photographs “established continuities of self and families and made biographies and genealogies visible”. The albums of fashionably dressed mixed-race women, dating from the decades after the American Civil War, distanced their owners from the trauma of slavery and rape and became meaningful for the entire group of women of color forging their new identities (

Jenkins 2020, p. 30). Such work on non-Jewish people who experienced racist violence is relevant for Jewish families, especially for those whose links to the past were shattered traumatically in the twentieth century.

Marianne Hirsch (

1997) recovered memory from old family photographs, including those of her own Jewish family who experienced the Shoah. Using her imagination, she sought to convert memories that were buried in the photographs into living memory relevant to the present. Hirsch’s concept of “postmemorial work” involves an effort to reactivate distant memory from photographs, within the context of a traumatic family narrative, by a deeply connected later generation that has no empirical knowledge of the first-generation subjects portrayed (

Hirsch 2008, p. 111). Trauma is inherent in the biographies of some of the Jewish families whose albums survived the twentieth century, such as the albums of the Dreyfus and Freiberg-Deutsch families, described below for the first time. Trauma is not, however, a necessary theme for the reactivation of nineteenth-century albums for genealogical purposes.

Few scholars have studied nineteenth-century albums created by Jews.

Nebahat Avcıoğlu (

2018) looked at immigrant narratives in the album of Hungarian-born Elisabeth Leitner, née Saphir (1842?–1908), a cosmopolitan woman who drifted between empires and nations throughout her life, immersing herself in the local culture and making friends locally before moving on.

Michaela Sidenberg (

2020) published an overview of the 23 multi-generational Jewish family photograph albums that are preserved in the Jewish Museum of Prague. She noted that most of these albums, and many more whose whereabouts are no longer known, came into the museum’s collection from the Prague

Treuhandstelle Warehouses, where the Nazi authorities collected the movable property of deported Jews from Prague and its environs.

Lavie Shai (

2014) published his study of the family album of the Valero bankers in Jerusalem, focusing on the album’s revelation of the history of photography in Jerusalem and the Ottoman Empire. Daniela Götz examined an unlabeled, early-twentieth-century Austro-Hungarian album. She studied the dedications and annotations on the backs of the photographs as well as the subjects’ dress. A postcard addressed to Ludwig Beran, dated 1917, showing a young woman and a three-month-old baby led Götz to identify only Ludwig Israel Beran (1866–1942) and nobody else in the album. As many Jews named Beran perished in the Holocaust, this album may be all that remains of his family (

Götz 2016).

In her publications in British and French genealogical society journals, Klein argued that nineteenth-century Jewish albums reveal meaningful narratives about a family’s cultural identity, migration, international networks, and leisure activities. In one study, she focused on the albums of Anglo-Jews, particularly those in the Salomons Museum at Broomhill, near Tunbridge Wells (UK), and others in the author’s own family archive (

Klein 2020). She also extracted genealogical discoveries from the Crémieux (

Klein 2021, p. 15 n. 29), Ettinger (

Klein and Ginzberg 2021), and Szulc-Bertillon (

Klein and Chenu 2023) albums discussed below. This article examines the concept that such albums can serve as sources for genealogists.

Jewish men and women exchanged and collected portraits, which they displayed in albums. Several studies of non-Jewish albums (for example,

Warner 1992, p. 30;

Di Bello 2007;

Siegel 2010, p. 140) have claimed that the collection and arrangement of portraits in an album was a predominantly female pastime. In the nineteenth century, Jewish men were more likely to maintain international contacts with family members for business and philanthropic purposes, whereas Jewish women more frequently took on the role of keeping up with their aging parents, married siblings, cousins, in-law relatives, and all aspects of family news, including the births of children, grandchildren, and great-grandchildren. Women were indeed more likely to become collectors and makers of family albums, and their albums are more likely to reveal genealogical information. Men, however, did sometimes become collectors and album makers. In the case studies discussed below, the Crémieux, Dreyfus, and Freiberg-Deutsch albums reflect women’s work and serve as primary genealogical sources. In contrast, the portraits in the Melchior album belonged to a man interested in photography; he maintained his own photographic studio and also collected photographs of his extended family. He or his wife may have arranged the album. The Szulc-Bertillon, Ettinger, and De Beer albums display portraits collected by both husband and wife. The case studies below are a sampling of Jewish family albums with genealogical narratives.

The albums of bourgeois Jews show the established Jewish elites, in some cases, and the nouveau riche, in others, in all their finery. Photography historian Julia Hirsch and dress historian Lou Taylor warned that the photographic studio may present “a chamber of fictions” (

Hirsch 1981, p. 70) and cautioned against “reading” clothes in nineteenth-century portraits (

Taylor 2004, p. 163). For bourgeois Jews, as Marcel Proust revealed, the visit to the photographer was an occasion to show off one’s latest sartorial acquisitions (

Proust [1913] 2013, p. 166). Such Jews had no reason to pose in someone else’s clothing or appurtenances, except for a fancy-dress ball or a traveler’s souvenir for which a costume could be rented. What is known about the wealth of the Jewish album makers strongly suggests that they, their family, and their friends wore their best garments taken from their own wardrobes for their portraits and that these images convey an accurate testimony of pedigree and class.

“Genealogy” encompasses the study of families and family histories and the tracing of their lineages. Although the Jews’ albums did not document family history in any organized or hierarchical fashion, they shaped the manner in which family history could be remembered. As conversation pieces, they encouraged viewers to ask questions about ancestors and, in this way, facilitated the handing down of genealogical memory. Who are these people? How are they related to each other? How, when, and where did they live? Who is missing from the family album? Vintage albums are fascinating catalysts for visualizing and discovering family history.

2. Methodology

A series of activities may enable the genealogist to reactivate genealogical narratives, construct or extend a family tree, and/or trace family migration. John Berger, who studied how people look at and understand photographs, observed that “To read a photograph, we need to know the historical context” (

Berger and Mohr 1982, p. 109). To read a vintage portrait album, the first step requires the careful documentation of all the textual and pictorial information in it, including on the cover, each cardboard page, and both sides of the photographic cards, to extract names, relationships, dates, and any other clues. In addition, the family historian studies the signs, gestures, and other non-linguistic forms of communication, including facial features, hairstyles and head-dresses, costumes, uniforms, office regalia, and accessories, such as jewelry and medals. Textual information, including names, locations, and dates, as well as semiotic information gained from the visual clues, can lead the genealogist to search for contextual material in family, community, and state archives; military records; cemetery records and gravestones; and newspapers and journals. Books, other pictorial sources, and interviews with the descendants of the original owners of the album may contribute further information about the portraits in a particular album. In addition, facial recognition software may assist with the naming of relatives, as Scott Genzer’s pioneering work has shown (

Genzer 2019).

The genealogist cannot assume that every portrait in an album depicts a family member. The social aspect of exchanging portraits nevertheless helps the researcher of family history when a dedication on the photographic card names the relationship of the donor to the collector, e.g., “from your sister Henriette” and “to my dear aunt Flora”. Such inscriptions are usually on the reverse side of the photograph and become visible only when the card is extracted from the album. Occasionally, albums also contain genealogical information inscribed on the album’s page, added by a descendant sometime in the twentieth century, such as birth and death dates, or the relationship of a subject to the new owner of the album (grandmother, cousin, etc.). Also, in some instances, portraits have been labeled on the album page and then removed or replaced with another portrait (as in the Szulc-Bertillon album described below). The remaining name below the empty frame may prove helpful to the genealogist.

The name and location of the photographers of an album’s nineteenth-century portraits, printed on the base and/or reverse of the portrait card, enables the mapping of family dispersal. As the album format hides this information, it is necessary to extract the card from the album to access this, a difficult task that the keepers of such albums do not always permit. The Toitū Settlers Museum in Otago, New Zealand (see the De Beer case below), the Center of Jewish History in New York (viz., the Freiberg-Deutsch album and a few others in their collection), the Jewish Museums of Belgium, Prague, and Sweden, the Center for the History of the Jewish People in Jerusalem, the Museum of Jewish Art and History, Paris, and the Salomons Museum in England have photo-documented or enabled the photo-documentation of both sides of the portrait cards in their nineteenth-century albums. The Jewish Museum of Prague, however, has not digitized page views, and therefore, any extant written text identifying sitters is not visible to viewers. In contrast, the National Library of Israel, the Rothschild Archive in London, the Anglo-Jewish Archive at Southampton University, and the Jewish Museum of Denmark (two Melchior albums and four Meyer family albums) did not permit this, limiting the reactivation of genealogical memories of migration, as well as the search for dedications and genealogical information on the reverse of the cards. Other institutions, including the Göteborg City Museum and the National Library of Sweden, have not documented their albums. The Jewish Museums of Berlin and Frankfurt have noted the photographers and their locations on only some of their Jewish albums and not others.

Facts and information about a particular album do not necessarily generate a genealogy. Relationships between the portraits in an album are not instantaneously obvious. The family historian therefore seeks connective threads in the collection of photographs, in juxtapositions, and in signs on both sides of the photographic cards. Two or more cards placed together or facing each other, taken by the same photographer at the same time, are likely related—a man and wife or a couple and their child/ren. Geographic information on the photographic cards, where visible, may reveal migration and family dispersion or merely bear witness to a business trip or a holiday at a spa or seaside resort. External contextual information, such as extant family trees (even if incomplete), biographies of owners and/or subjects, places of residence, occupations, and political events, helps the viewer extract, develop, and revive the genealogical stories embedded in an album. To cite Berger again: “without a story, without an unfolding, there is no meaning” (

Berger and Mohr 1982, p. 89). As both

Langford (

2008) and

Hirsch (

2008) stressed, imagination, interpretation, and discussion of the album and its contents are as necessary now as in the past for revitalizing these albums, making them relevant to individual spectators today, and for “reading” genealogy in these memory objects.

Unfortunately, some albums offer no visible evidence of the name of the person whose collection is displayed or of the identity of any of the portraits. Hand-written names and dedications are often hard to decipher. In addition, as genealogists well know, the search for information about a name may involve consideration of a variety of spellings in numerous languages and alphabets.

This study presents four case studies to show how family albums of nineteenth-century bourgeois Jews could become catalysts for genealogical discoveries. It also discusses four other Jewish albums that display visual genealogies, albeit in no organized fashion, and two other case studies from which genealogical memories of migration are revived. Nineteenth-century portrait albums owned by Jews that house only celebrity collections are beyond the scope of this study.

The choice of which albums would serve as case studies was determined by their potential for genealogical study. An unlabeled album without any personal names is unlikely to reveal genealogical discoveries, analogous to an unmarked or severely corroded gravestone. Some albums, such as the three Prussian Burchardt family albums in the Jewish Museum Berlin, two in the Museum of Jewish Art and History in Paris that belonged to the sister and sister-in-law of Alfred Dreyfus (the French artillery officer accused of treason in 1894), and the four made by Ida Samuel, her mother Jane Spiers, and her father-in-law Salvador Levi in the Jewish Museum of Belgium, portray family genealogies that have already been well documented. The Melchior and Salomons families, whose albums show aristocratic genealogies, also have detailed family trees. The Schames album, in the National Library of Israel (NLI), which offers evidence of family dispersion in the wake of Nazi racial laws, may have been a good candidate for another genealogical case study. However, as mentioned above, the NLI, as well as some archives and museums, did not permit the extraction of photographs from their albums to access all of the data hidden on the reverse of the portraits and have thereby limited the possibilities for genealogical research. Full-page scans are missing from the online view of some albums, including the many in the Jewish Museums of Prague. Other albums, such as those in the Jewish Museum of Amsterdam, may yet prove useful for genealogical research. Many of these albums were donated by living descendants, except those in the Jewish Museum of Prague and those in the Center for the History of the Jewish People in Jerusalem, which were mostly looted by the Nazis. Institutions, however, have often not kept records of the provenance of their albums. A brief summary of all of the albums named in this article is provided in

Appendix A.

3. Case Studies

Text and context are needed to give genealogical meaning to the visual archive within a portrait album. The case studies below are a result of an examination of the content of each album and each of its portraits, as well as research to provide the backstories of the named individuals and their families. Only two of the albums mentioned in the case studies above, the Ettinger and Berthe Dreyfus’s albums, remain today in the hands of relatives of the album compilers. The Szulc-Bertillon couple has no surviving descendants. Descendants and relatives of the sitters and makers of the albums in public archives and museums are no longer connected to these objects, voluntarily or involuntarily.

3.1. Genealogical Discoveries

The albums presented in the case studies below formed the catalyst for original genealogical research. Unlike some genealogical sources, Jewish albums usually show matrilinear as well as patrilinear relatives: women and girls, as well as men and boys.

The fully labeled Crémieux album revealed just one unknown female relative, whereas a few unknown female relatives were discovered via the unannotated Ettinger album. In contrast, research of the annotated Szulc-Bertillon and Dreyfus albums led to the construction of extensive, hitherto undocumented family trees. The Szulc-Bertillon album, in particular, added women to the genealogy of a highly musical family in Warsaw. The Dreyfus album revealed an international cousinhood.

3.1.1. The Crémieux Album: A Genealogical Memorial

Most albums that have been donated to institutions for preservation are either unlabeled or partially labeled. However, someone had labeled the contents of the “Adolphe Crémieux family album” before its deposit in the French National Archives, together with other archival material related to the French politician, who was also a Jewish activist (French National Archives 369ap/3, dossier 3). The names beneath each portrait facilitated the search in newspaper archives, scanned books, and genealogical websites for information about each one.

The lineage of the old French Jewish Crémieux family is well documented. This album, however, contains a collection of portraits that clearly belonged to Amélie Crémieux (1800–1880), née Silny, the wife of Adolphe Crémieux, and portrays her two sisters, who were born in Metz. It is unusual in that 85% of friends and family in the portraits had died by the time the album was assembled in its present form. She therefore created most of the album as a memorial collection, rather than a work in progress. It is of special interest, genealogically, for revealing her elder sisters and some of the women who, like her, married into the Crémieux clan. Her small album does not contain any portraits of herself, her husband, or her children. Only 9 of its 33 portraits portray men. The album contains a sampling of her mostly female non-Jewish friends, whom she met at literary and musical salons, as well as Jews from the financial and social elites of her era.

Although Amélie Crémieux converted to Catholicism in 1846, the sixteen portraits of Jews within the album defines it as a small repository of Jewish genealogical memories. Eugénie Beer (1793–1869) and Rose Berncastel (1794–1876) are among the few members of her own family on display. Eugénie Beer, Amélie’s eldest sister, did not appear in any published family trees (e.g., Geni.com, geneanet.org, myheritage.com) prior to Klein’s publication (

Klein 2021, pp. 8, 15, n. 29). A book about a Viennese musician led to the discovery that Eugénie Silny was a talented pianist who married Markus (Meschulam) Hirsch Beer (1785–1857), one of the leaders of the Jewish community of Vienna prior to 1848 (

Kroll 2007, pp. 120, 248, 358, 367, 379). Eugénie must also have sent Amélie the three portraits of her grandson’s beautiful young wife, Henriette Kann, née Biedermann, who died aged 27 in 1865 and is memorialized in this album.

Klein’s publication led Jacques Gerstenkorn to identify the portrait of his great-grandfather Samuel Mayer in this album (private correspondence, 23 September 2021), whom Klein had mistaken for someone else. Gersternkorn was excited to see the image of his ancestor. Samuel Mayer (d. 1856) married Ernestine Berncastel, a daughter of Amélie’s sister, Rose. Ernestine’s sister, Adèle Weil, is well-known as the grandmother of Marcel Proust.

The album also contains portraits of two women who married into the Crémieux family: Esther (1800–66), née Lévy-Salvador, whose husband Jacob Vidal Crémieux was a cousin and childhood friend of Adolphe’s, and two portraits of Esther’s lovely daughter-in-law Leontine (1837–1869), the daughter of the banker and Strasbourg Jewish community leader Achille Samuel Ratisbonne. Leontine was only 32 when she died.

3.1.2. The Ettinger Album: Rabbinic Genealogies

Jewish albums were predominantly owned by individuals or families who had inherited wealth or had made their money in finance or business. Hayim Ettinger (1857–1928) was an observant Jew, a successful merchant, and a philanthropist. His maternal grandfather was wealthy; there is no evidence that his own father was a man of means. Nevertheless, the Ettinger album memorializes an extended and dispersed family, including the wives of two rabbis, whose given names were omitted in an old book of rabbinic genealogies (

Beilinson 1901, pp. 170–73).

In 1922, 65-year-old Hayim and his wife Esther (c. 1852–1941) left Odessa for Palestine with their leatherbound family portrait album. Today, the Ettingers’ relatives may not be able to find the graves of many of their Eastern European cousins, who, the album reveals, lived in the late nineteenth century in Kiev, Warsaw, Uman, Mezritsh (now Międzyrzec Podlaski, Poland), Odessa, Riga, Kishinev, and elsewhere, but they can now visualize them in the family album and re-create their stories. The published study of

Klein and Ginzberg (

2021) related stories about the Ettinger couple and album. It did not focus on genealogy, although it led to a few genealogical discoveries.

At first glance, Arnon Ginzberg, who now owns the album, could only identify two of its fifty portraits from copies he had seen in his grandfather’s home: the simply dressed family matriarch on the first page of the album was Hayim Ettinger’s paternal grandmother, Mary Simḥevitz (d. 1865), and on one of the inner pages, a photograph taken in Uman of the Ettingers’ son-in-law in a fedora hat, Meir David Piness (1872–1936). According to the book containing rabbinic genealogies, Simḥevitz was from Minsk (now Belarus), the unnamed daughter of Rabbi Hayim Simḥevitz was from Minsk, and the wife of Yakov Hillel Ettinger, Hayim’s grandfather, was also from Minsk. The same book revealed that Dov Piness of Rozhinoy (now Ruzhany, Belarus) married one of Mary’s daughters. He was likely a relative of Ettinger’s son-in-law (

Beilinson 1901, p. 170).

Arnon’s nephew, Alon Ginzberg, and Klein examined both sides of each photograph, consulted historical family documents that had lain untouched for decades, contacted a relative who had immigrated to Israel from the former Soviet Union in 1990, and scoured newspaper archives in Hebrew and Yiddish, as well as online family trees, for names and connective threads. Anna Grudinovker and Shoshana Levit kindly translated nineteenth-century inscriptions. Klein and Ginzberg ultimately succeeded in identifying 19 people in the album and expanded the entangled Ettinger–Ginzberg family tree, where the children of one branch married the children of another branch, as in the Rothschild and so many other Jewish families.

The Ettingers’ social world began in a well-to-do Orthodox environment, where women wore a head-dress, a

sheitel, and boys attended yeshiva, men engaged in business as well as Torah study, and family names repeated themselves generation after generation. Hayim, who features as both a child and an adult in this album, was born in 1856 in Uman in the Russian Empire (now in Ukraine). He was born a few months after the death of his father, also named Hayim, whose grandfather was the distinguished Polish Talmudist Yehiel Michl Ettinger of Rawer (now Rava Mazowiecka, Poland), also known as Michli Rawer or Michl Ettinger Rawski (

Landa 1837, p. 1), who headed a delegation of Jewish deputies to Csar Alexander I in Paris (cited in

Fijałkowski n.d.). Baby Hayim was the third son of Hayim Ettinger (senior) and Hannah, née Tulchinsky, who also features in the album. A few years after her husband died, Hannah wed Aryeh Leib Ginzberg, a Torah teacher and widower from Pinsk (now Belarus). She gave birth to more children in Uman before he also died in 1866 (

HaCarmel, 12 Adar 5626, 134). The album contains two portraits bearing the names of Uman photographers from the 1880s or 1890s of yet-unidentified young women.

Alon Ginzberg knew that Hayim (junior) and his two brothers Yakov Hillel and Yona Ettinger had two half-brothers, Berish and Arie Zeev Ginzberg; the album led to the discovery of a half-sister as well, named Rachil. A passport issued in Riga, now in the Yad Vashem Archives (in M. 43, Archives in Latvia, file no. 2756) and dated 1922, provides a portrait of “Rachil Leiba Berlin, née Ginsburg,” born 12 September 1863. This document, which was uploaded to geni.com, names her parents, Leyba Ginsberg and Chana Ginzberg (Etinger), as well as her husband, Berka Zalmanovich Berlin. Two portraits in the album, from Riga, one of a man and one of a woman, show newly married Berka and Rachil, confirmed by face-matching software.

A portrait of a man with receding dark hair and a waxed mustache taken in Kishinev led to a search for relatives in that city. Alon Ginzberg discovered that Lova Ginzberg, a descendant of Berish Ginzberg, who settled in Israel after the dissolution of the Soviet Union, kept a family tree and some old photographs. One of his photographs enabled the identification of a woman seen posing with her husband for a snapshot displayed in the Ettinger album. This was Klara, born in 1882, a daughter of Berish, and her frail-looking husband, Avram Gendrikh, born in 1881, who lived in Kishinev. Both were murdered in the Shoah (Yad Vashem Archive Data Base, s.v. Gendrikh). Face-matching software was not needed to assert that the portrait of the much younger man with the waxed mustache, photographed in Kishinev, is Avram Gendrikh.

Alon Ginzberg knew that Hayim Ettinger’s wife was named Esther but did not know her maiden name or her place of birth. With help from Yosef Vidman in B’nei Brak, the 1866 hand-written marriage contract in Arnon Ginzberg’s cupboard provided the answer. Esther was the daughter of R. Shimon Papirna and lived in Mezritsch, some 800 kms north-west of Uman. A portrait in the album taken in Mezritsch is evidently her mother. A memoir in an Israeli newspaper, Yediot Aharonot (1959), by Yehoshua H. Yeivin, the grandson of Esther’s sister, related that Reb Shime’on was from Paritch (now Parichi, Belarus), a Talmudic scholar and entrepreneur with broad literary interests who sported a brown top hat, a fashion favored by the learned Jews of the “Mitnagdim” (“opponents” of Hasidism). This information enabled the identification of his portrait in the Ettinger album. Yeivin also mentioned that Shimon’s wife was named Feige and she withdrew to her room after her husband died. The album preserved two portraits of her, one in her prime and one in her retirement. Yeivin’s memoir provided a few more additions to the fast-growing Ettinger family tree.

Thirteen portraits taken in Odessa date from the Ettingers’ residence in that city during the 1890s and early 1900s. They show Hayim and Esther, their son and daughter, her husband and son, among others. Hayim built a profitable business in the Black Sea port, became a leader of the Jewish community, and an active Zionist. Burial records in Tel Aviv provided dates for the births and deaths of Hayim, his daughter, and his grandson.

The aforementioned book with rabbinic genealogies (

Beilinson 1901, p. 173) enabled the identification of a portrait of an elegant, elderly woman photographed in Bobruysk (now Babruysk, Belarus): she had to be Esther’s pious and affluent aunt, the wife of Michael Margolioth of Bobruysk, daughter of Shaul Papirna of Paritch and his wife Dvora Margolioth (

Figure 2). She wears a

sheitel in her portrait, as well as earrings, a fancy brooch, and tailored cuffs. Her hat is fashionably decorated with feathers. Like many other women in the rabbinic genealogies, Mrs. Margolioth’s first name remains unknown. Her portrait preserves her memory.

Finally, research of this album led to the discovery of another album held by Yoram Yeivin in Hod Hasharon, Israel, the grandson of the writer of the above-mentioned memoir published in Yediot Aharonot and the great-great-grandson of Esther’s sister, Tsina Golda Papirna. His album was partially annotated by his father and includes a portrait of Esther’s sister. Klein and Ginzberg’s findings expanded Yeivin’s family tree. Dedications on the back of the portraits in the Yeivin album include the names and images of hitherto unknown Yeivin relatives.

3.1.3. The Szulc-Bertillon Album: A Genealogy of Musicians

Wives and daughters, unnamed in rabbinic genealogies, have often been ignored in the biographies of Jewish musicians. The Szulc-Bertillon album led to the discovery of hitherto forgotten members of a large, extended musical family in nineteenth-century Warsaw.

Researching the Parisian Bertillon family in 2017, Alain Chenu acquired a thick leatherbound portrait album in a sale of Bertillon papers. The album had probably been a wedding present given to Jacques Bertillon (1851–1922), an atheist, and Caroline Szulc/Schultze (1867–1926), who was born into a Jewish family in Warsaw. They both studied medicine in Paris, he a few years before her, and married in 1889. The couple began to fill the album with their own collections of portraits, including some of his family members, some of hers, and medical and feminist friends. They later added portraits of their two daughters, which were removed at some point. The Klein and Chenu study, published in French (

Klein and Chenu 2023), discussed the non-genealogical narratives that they found in this album, which are beyond the scope of this study, and attempted to construct Caroline’s Polish genealogy, helped by the annotations on some of the album’s pages and dedications on the back of some of the album’s portraits, skillfully deciphered and translated by Monica Kluzek.

Polish and French newspapers and other archives, as well as cemetery listings, assisted in the documentation of Caroline’s highly musical family.

Leon Tadeusz Błaszczyk’s (

2014, p. 248) book on the Jews in music in Poland in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries proved a useful but not entirely reliable source. The numerous spellings of Karolina/Caroline’s surname in Polish, Russian, Hebrew, Yiddish, and French—Szulc/Szultz/Schultz/Shultze—as well as that of her Wakhalter/Waghalter/Wachalter cousins, burdened the search. Similarly, the first names of her male relatives varied according to the sources consulted—Adam/Abram/Abraham; Icek/Iccek/Isaak/Itzhak; and Henryk/Hayim. Following the textual and semiotic clues in the album, Klein and Chenu sketched the genealogy of Caroline’s Jewish family to highlight its musicality and its role in the musical activities of late nineteenth-century Warsaw.

The album exhibits three portraits of Caroline, the latest of which was her gift to her fiancé, dated 22 June 1889, according to the dedication on the reverse. The civil registration of the couple’s wedding on 11 October 1889 notes that the bride, “Caroline Szultz, dit [pronounced] Schultze,” was born in Warsaw on 20 May 1867, daughter of Abraham Szultz, a 59-year-old musician living in Warsaw, and Elka Kaliska, deceased. The album displays a carte de visite portrait of her father, according to the Polish inscription, “to my dear daughter, Caroline,” on the reverse. The annotation beneath the portrait noted the date that Caroline’s father died, 11 March 1906. On 30 March 1906, the

Gazeta Kalisk reported that the 78-year-old double bass player, Adam Szulc, had died in Paris. Records of the Warsaw Theater of Varieties showed his employment as a double bass player in 1870 and 1871 (

Błaszczyk 2014, p. 248). Błaszczyk reported erroneously that this musician was named Adam Abram Szulc, born in 1827, and was buried in the Okopowa cemetery in Warsaw in 1902. The elaborate headstone in the Warsaw cemetery, engraved with an image of a hand placing coins in a charity box, marks the grave of the philanthropist Abram Schultz, son of Saul, a wealthy merchant, who died at the age of 75 on 14 May 1902 (Virtual Cemetery (jewish.org.pl), sv. Schultz). This error highlights the necessity to check primary sources and the danger of relying solely on secondary sources.

A portrait on the same page as Caroline’s father is apparently her mother. The dedication on the reverse, “as a souvenir to the much-loved lady-doctor from her loving and devoted mother”, is signed Paulina Szultz. This was not the mother’s name, according to the marriage certificate. Klein and Chenu were unable to discover whether Paulina was Caroline’s sister, aunt, or step-mother. We were also unable to find any Polish records of Elka’s birth, marriage, or death.

Another portrait revealed Caroline’s sister, Henryka, inscribed with “A token of remembrance! For my dearest sister, Karolina, a sign of affection from loving Henryka Szultz, Warsaw 2 September 1888.” Two other portraits taken in Warsaw, apparently show Caroline’s maternal relatives, the young adults Hélène Kaliska and Julien Kaliski. A penciled annotation in the album notes that Hélène became Mme Neymanowicz, but no other records of this woman were found.

The album provided many more entries for Caroline’s family tree. Two early photographs in the album, with similar dedications on the reverse, taken at the same studio, show Caroline’s uncle, Henryk Szulc, who closely resembles Caroline’s father. Henryk wrote on the back of his portrait: “To my dear niece Karola, Uncle Henryk Szulc.” A photograph of two young women in their late teens and in Polish dress (

Figure 3) was inscribed with the following: “To my dear cousin, Karola Szulc, your loving cousins Emilia and Felicia Szulc.” These two photographs are dated “Warsaw 25/7/85.” A penciled comment in the album added decades later notes that the two girls are the sisters of “Joseph Szulc (le musicien). Félicie est morte [Felicia died, presumably unmarried] et Emilie (Mme Apenszlak) mère de [mother of]…” Emilie evidently had a child, but the writer did not know its name. The Bertillon couple would have met Felicia’s younger brother, Joseph Szulc (1875, Warsaw–1956, Paris), a virtuoso pianist who arrived in Paris in 1899 to work with Jules Massenet. He composed a symphony and violin sonata, wrote light operas, and set Verlaine’s poems to music. He also conducted orchestras in Brussels and Paris and married a non-Jewish operetta singer, Suzy Delsart (

Letellier 2015, p. 386). Could Emilie’s child have been Leonora Apenszlak, born in 1904, who lived in Warsaw in 1939 and survived the war,

https://new.getto.pl/en/People/A/Apenszlak-Leonora-Unknown (accessed on 5 November 2023)? Felicia was about the same age as Caroline.

Błaszczyk (

2014, p. 249) provided a brief biography of Henryk Szulc and his five musical sons, one of whom was the virtuoso pianist and composer Joseph in Paris. This biography says nothing about his daughters, although the album reveals that he had at least two. Błaszczyk mentions the cellist Leon (1857–1935), clarinetist Maurycy (c. 1865–d. 1936), violinist Michał (d. c. 1930), and Bronislaw (1881–1955), a horn player and composer who arrived in Palestine in 1938. Błaszczyk noted that Henryk Szulc (1836–1903), a composer and conductor, worked as a violinist in the Grand Theatre and Opera Orchestra of Warsaw and taught the double bass at the Warsaw Conservatory.

Leon Szulc visited the same photographer as his sisters and father just before Caroline left for Paris. On the reverse of his portrait, he wrote, “A ma chère cousine Caroline, souvenir, Léon Schultz. Varsovie, le 27 juillet 1885.” Leon played his cello in the Grand Theatre and Opera Orchestra in Warsaw. His brother Maurycy, on the same album page as Henryka and Felicia, studied clarinet and for many years played this instrument as well as a base clarinet in the Warsaw Philharmonic Orchestra (

Błaszczyk 2014, pp. 250–51).

Henryk’s brilliant career was reported in the press on several occasions (e.g.,

Echo Muzyczne, 2 March 1895, 103;

Kurjer Warszawski ier 21 March 1900, 2, which also stated that his great-grandfather was a musician). Henryk’s lengthy obituary in the

Echo Muzyczne (20 February 1903, 178) reported that he had

six musical sons and a prodigal grandson. Henryk’s sixth son, Hermann, omitted by Błaszczyk, posed with his father and is named in the Szulc-Bertillon album. The dedication in French on the portrait of Henryk and his son says, “à Mlle Caroline Schultz, docteur en médecine, souvenir sympathique de son oncle et cousin.” It must date from 1889, before her marriage. The boy appears to be about 17 years old and was therefore born ca. 1872. Four years later, in 1893, the same young man sent Caroline his portrait, with a dedication in English: “To my dearest cousin, as a slightest token of regard and admiration, Hermann, Berlin, 11/12/93.” Another obituary of Henryk’s in the

Kurjer Codzienny (12 February 1903, 2) says that the talented grandson performed at the age of ten at Warsaw’s Music Society. This has to be Leon Szulc’s son, Jozef/Joseph, born in 1893, who had proved his great talent as a pianist at a concert in 1903 (

Kurjer Codzienny, 12 February 1903, 2) and later became a professor of piano in Strasbourg. He survived WWII in Cairo, where he founded a conservatory (

Błaszczyk 2014, p. 250). Leon’s second son, Roman, also escaped the Nazis and worked as a timpanist in the Boston Symphony Orchestra (

Błaszczyk 2014, p. 251).

The album displays another of Caroline’s cousins, a teenager in school uniform, whose dedication says, “To my cousin Caroline, a token of affection and respect. Henryk. 8/6/[18]85.” The penciled annotation says that this was Henryk Waghalter or Wakhalter. This led to the discovery of another branch of Caroline’s genealogy. The population registers on JRI Poland,

https://www.jri-poland.org/ (accessed on 5 November 2023), revealed that the Waghalters and Szulc families were related through several marriages. Adam’s parents were likely Jakub/Jakob/Yakov Szultz (d. 14 April 1876), a cellist, and Fajga/Fayge Waghalter. Adam had an aunt or a sister who married a Waghalter/Wakhalter, who had a son named Henryk.

Błaszczyk (

2014, pp. 265–67) listed ten musicians in the Waghalter family, who were born in Warsaw, including Henryk (1869–1961), who became a renowned cellist. Henryk and his younger brother Jozef (1880–1942) played in the Jewish Symphony Orchestra in the Warsaw Ghetto, but only Henryk survived the war. A website,

www.waghalter.com (accessed on 5 November 2023), devoted to the compositions of his talented younger brother Ignaz (1881–1949) reported that Henryk, Jozef, and Ignatz had another 18 siblings, including Wladyslaw (1885–1940), who played in Berlin’s German Opera orchestra. Both their parents were musicians, and their great-grandfather, Lejbuś Waghalter (1790–1868), was known as the “Paganini of the East” (

Błaszczyk 2014, p. 267). Ignatz left Europe in 1937 and died in New York. Warsaw newspapers mentioned two other noteworthy young cellists from this family, Aloiza Waghalter and Hipolyt (b. 1897), who became a soloist in Warsaw’s Music Society Orchestra (e.g.,

Kurjer Warszawski, 13 June 1891, 1 and 15 February 1905, 3).

Caroline was related to most of the 23 Szulc musicians and 10 Waghalter musicians listed in Błaszczyk, as well as others not listed there. She had no grandchildren. Thanks to the dedications on the reverse of the photographic cards and the annotations on the album’s pages,

Klein and Chenu’s (

2023, pp. 32, 36) study discovered some of the musicians’ mothers, wives, and sisters who had not interested music historians.

3.1.4. The Dreyfus Album: An International Cousinhood

Louise Dessaivre inherited an album created by her great-grandmother, Berthe Dreyfus, who was born in Antwerp in 1879. This album, too, became a catalyst for searching genealogical websites and public archives in order to construct Berthe’s nineteenth-century family tree, the family’s dispersion, and their genealogical memories. In 1901, she and her husband, Ferdinand Lazard, moved to Amiens, France. In 1944, they were deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau and murdered,

https://hal.science/hal-03425716/ (accessed on 5 November 2023), and all their belongings were pillaged. However, Berthe had already given her album and autograph book to her daughter Simonne Audelet, who survived the German occupation in hiding with her non-Jewish in-laws, and these heirlooms remained intact.

The 91 photographic portraits that Berthe collected in her album spanned from the 1860s to the early years of the twentieth century. She penciled in the names of many portraits on the cardboard pages. A few cards have dedications on the back. Dessaivre could identify Berthe’s parents, Hélène Michel (1845–1936) and Arnold Lucien Dreyfus (1847–1913), Berthe’s sister Anna, her husband Alfred Dreyfus, and their daughter Hélène, whom Berthe had not named. Dessaivre recalled that Berthe and Anna had a sister, Céline, who died aged 16 in 1891 and who appears to be missing from the album. “The other branches of the family—the Philips, Krijns, Francks and Blochs are almost unknown to me,” wrote Dessaivre, “but my grandmother talked often of these cousins of her mother” (private correspondence, 24 September 2021). The album’s photographs have enabled the construction of Berthe’s nineteenth-century family tree, showing her maternal and paternal relatives.

The photographers’ details on the base or reverse of the portraits revealed the cities in which Berthe’s extended family resided and enabled localized searches of online databases. One maternal branch lived in Amsterdam, and another maternal branch remained in Antwerp. The paternal branches lived in Paris, although Berthe’s paternal grandmother came from the Moselle region of Lorraine.

The Dutch connection: Ten photographs from Amsterdam show the Van Messel and De Vries families. Dessaivre discovered that Berthe’s maternal aunts, Josephine and Marie Agatha Michel, both married Jewish Dutchmen, Juda van Messel of Leeuwarden and André (Asser Hijman) de Vries of Amsterdam, and their children, Marianne Van Messel and Marianna De Vries, were named after Berthe’s maternal grandmother, Maria Anna Krijn/Kryn (1828–1892).

The Krijn/Kryn family in Antwerp: Maria Anna Krijn/Kryn had at least seven siblings who survived into adulthood and married, discovered by searching for names that appeared in the album in several genealogical databases. While the name Krijn/Kryn was very popular in the Netherlands, especially among non-Jews, it was less common in Antwerp. Dessaivre was able to locate Maria Anna’s parents and siblings via Geneanet.com. Maria Anna’s youngest sister, Fijtje, married into the Philip family, as discussed below. Krijn relatives in the album include Maria Anna’s sister Marie, who married Maurice Grevel, and their brother, “Uncle Rick” (Henricus), who worked in the diamond business, his wife Catherine, and some of their children, who all lived in Antwerp. Two portraits showed a young woman named Anaïs Franck (1882–1927); a Google search revealed her husband, Frans Franck, a decorator and furniture maker, art patron, and initiator of Antwerp’s De Kapel group of progressive intellectuals. Berthe’s autograph book provided the clue to where Anaïs fit in the family tree. She had signed her entry “Cousine Anaïs Franck”. Anaïs’ maiden name, we discovered, was Anna Krijn, a grand-daughter of Henricus Krijn, Uncle Rick, and thus Berthe’s second cousin.

One of the larger portraits in the album showed a man with a mustache and a dark stripe down his pale trouser leg. He posed smugly, with a white dog perched on the table (

Figure 4). The penciled note beneath this portrait said, cryptically, “father of Bouneque?” The text on the back revealed that this was a passport photograph of “Michel Joseph Kryn,” Berthe’s grandfather, Joseph Michel, the husband of Maria Anna Krijn/Kryn, who adopted her name to mark their association. It was dated 25 October 1870 (or 1871, unclear) and countersigned by the Burgermeister of Antwerp, who attested to its authenticity. The online Directory of Belgian Photographers,

https://fomu.atomis.be/index.php/michel-kryn-j;isaar (accessed on 5 November 2023), lists Berthe’s grandfather, Michel Joseph Kryn, born in Maastricht in 1819. The directory notes that he had worked as a money exchanger before becoming an optician who created magnifying lenses for photography and sold stereoscopes. Berthe’s father, Arnold Lucien Dreyfus, who also initially worked as a money changer, took over his business, according to the directory.

The Paris jewelers: Berthe’s father had a sister, Sara Céline, who married a jeweler, Arthur Moise Philip, and they and their two children, Emile and Georges Arnold Philip, feature in the album. Emile and Georges both served in the French army, and Berthe displayed photographs of them in military uniform. Arthur’s brother, also a jeweler, Edouard Moise Philip, married Maria Anna Krijn’s youngest sister, Fijtje, whom Berthe called Caroline, and their daughter, named Berthe Helene Philip, married her first cousin, Georges Arnold Philip. Edouard, his wife, and their two children are seen and named in the album. The Philip family is therefore related to Berthe Dreyfus, the album owner, via both her parents.

Berthe labeled two of the album’s portraits “

Grand mère Philip” and “

Grand père Philip,” although they were not actually her own grandparents (

Figure 5 and

Figure 6). The photograph of “grandmother”, adorned with an elaborate lace head covering and Biedermeier style of dress (identified by Lou Taylor, personal correspondence, 20 September 2023), reproduces an amateur watercolor painting. She was not the grandmother of Berthe Dreyfus, the album owner; her title is honorific. Breslau-born Annette Jacob (1802/1803–1886) was the mother of the jewelers Arthur and Edouard Philip and the wife of Jacques/Jacob Moyse Philip (1801–1886, see

Figure 6), also a Parisian jeweler. As described below, an aristocratic-looking ancestor in one’s album implied an aristocratic pedigree.

The Lorraine relatives: There is no doubt about the bourgeois status of Berthe’s portly, double-chinned Parisian paternal grandfather, Isidore Dreyfus (1814–1883), clearly a successful businessman, and his tightly corseted wife, Philippine Aron (1812–1869) (see

Figure 7). The album revealed descendants of Philippine Aron, who came from Phalsbourg, a small town in the Moselle region, just east of Strasbourg, where Jews had lived from the time of Louis XIV. Mme Edinger, the Bloch family, and Commander Leopold Stettheimer/Stetemer, we discovered, were all connected to the Aron family. Mme Edinger was Philippine’s sister Caroline, and an unlabeled photograph on the same album page, taken by the same Parisian photographer, must be Caroline’s daughter, Clara Coblentz. Clara’s daughter Berthe married Sam Bloch, and their two girls, another Berthe (the fourth in the family!) and Andrée, all appear on page 15 of the album. Commander Stetemer was not in uniform, but he had a fine, waxed mustache and a pin in his lapel. His mother, Esther Estelle Aron of Phalsbourg, was apparently a cousin of Philippine and Caroline.

Our research enabled the construction of extensive and intertwined family trees. We were unable to discover the identity of “Tante Merek, mother of Elise.” Merek may be a diminutive of Maria Josepha Ravays, the wife of Maria Anna Krijn’s brother Moses Krijn, or Margareta, a sister of Maria Anna, Moses, and Henricus, or the “tante” may signify an honorific aunt who is not actually related. We were unable to identify ten of the people in the album, most of whom are likely also relatives of Berthe, although she also displayed the family’s servants and portraits of friends, some of whom had signed her autograph book.

These case studies, and the other albums discussed below, maintained family networks and enabled descendants to visualize and learn about their ancestors.

3.2. Aristocratic Lineage

The collection of photographic family portraits enabled Jews to create a visual genealogy, intentionally or unintentionally, which portrayed their bourgeois heritage. Nineteenth-century Jews did not initially collect portraits to memorialize their family histories, although their collections of richly attired ancestors and descendants, preserved as family heirlooms and displayed in albums, came to serve this function. In the early nineteenth century, opulent Jews commissioned painted portraits of themselves and their wives and, on occasion, also their parents, imitating the non-Jewish aristocracy. The early-nineteenth-century portraitist could, of course, embellish the painting of a wealthy Jewish patron. In contrast, a photograph of a live model provided a more accurate likeness, although the photographic artist could touch up a print to make it more flattering. Descendants sometimes displayed photographic reproductions of their family’s painted portraits in their albums to convey an aristocratic pedigree, as in the Dreyfus album described above and the four examples below.

Gustav Przibram’s family album in the Jewish Museum Vienna (Inv. No. 4515) shows that he and his wife were proud of their aristocratic heritage. Gustav was the grandson of Aron Beer Przibram (1781–1857) of Prague and Therese Esther Jerusalem (1783–1866), who was Aron’s wife and niece. Descended from the eminent Rabbi Judah Loew ben Bezalel, the Maharal of Prague, Aron built an immense fortune in the textile business. He and his wife were richly dressed for their portraits in the Przibram family album. Most of the other 23 portraits in this album portray the families of Gustav’s parents, Salomon and Marie Dormitzer, whose mother was Therese Esther Jerusalem’s sister. This album also exhibits Gustav’s wife, Charlotte von Schey, and her ennobled Austro-Hungarian parents, the Jewish banker Baron Freidrich Schey von Koromla and his wife Hermine, née Landauer. The luxurious dress of the women, including the rich fabrics, jewelry, and lace, shows the family’s aristocracy, as well as three generations of its intertwined genealogy.

A much larger album—the largest in this study—belonged to the family of Israel Barendt Melchior (1827–1893) and spans four generations of an extensive family at the pinnacle of Danish Jewish society (Danish Jewish Museum, JDK0148x2). This collection of some 370 photographic cards portrays a highly interconnected Ashkenazic family, where marriages took place between uncles and nieces as well as with other members of the Danish Jewish elite, including the Henriques and Meyer families. The first page displays photographs of ancestors, including reproductions of painted portraits of Israel Barendt Melchior’s maternal grandparents, Lea/Galathea (1755–1814) and Lion Israel (1758–1834), dressed in the fashion of Napoleon’s empire (

Figure 8), and images of his parents, Gerson Moses Melchior (1771–1845) and Birgitte Melchior, née Israel (1792–1855). Yet another photographic card on the album’s first page reproduced a painting of Israel Barendt’s sister Henriette Melchior (1813–1892) sumptuously dressed in the late 1830s. These portraits attest to the family’s wealth in the early nineteenth century. Israel Barendt Melchior had seventeen siblings. Unusually, some of the pages in this album are organized genealogically, with photographs of Israel’s siblings’ nuclear families arranged together. For example, portraits of Israel’s sister Sophie (1809–1883), her ten children, and their spouses and children are followed by his sister Galathea (1818–1906), her German husband, Dr. Nathan Levi Marcus, and their children, displayed one next to another. Some portraits reveal the Melchior family’s participation in the pastimes of the leisured class, including masquerades, tableaux vivants, fancy-dress parties, and play acting in the salon.

Other Jewish album makers similarly exhibited photographic reproductions of long-dead ancestors in their albums, portraits of Jews who had acquired wealth in the eighteenth or early nineteenth century and formed part of the old bourgeoisie, as opposed to the nouveau riche Victorians. For example, Sir David Lionel Salomons (1851–1925), a photographer and an avid collector of photographic portraits, inserted a photographic reproduction (

Figure 9) of a youthful painting of his Dutch-born paternal grandmother, Mrs. Levi Salomons, née Matilda de Metz (1775–1838) (Salomons Museum, UK, Album 510), among the many portraits of his extended family and his friends. The original likely came from inside a locket or pendant. Her short curly hair (“coiffure à la Titus”) followed the French Revolutionary fashion (1790s), as did the choker around her neck. The ruffle on her bodice and the small shawl suggest a date up to about 1804 (Lou Taylor, private correspondence, 21 September 2023).

The reproduction of a painted portrait of Salomon Josephson (1784–1834), the first generation of the talented Josephson family born in Sweden, features in an album (

Figure 10) that belonged to the family of his son, the Swedish composer Jacob Axel Josephson and his second wife, Lotte Piscator (Jewish Museum of Sweden, album 1259). Jacob Axel converted to Christianity in 1841, yet his family album preserved a visual genealogy of 29 members of the Jewish Josephson family—Jacob Axel’s siblings and their families. Salomon Josephson was clearly already very wealthy when he posed, shaved and balding, for his painted portrait in a starched white stand-up collar, white dress shirt, and tie. His plump widow, Beate Levin (1791–1859), who was born in Copenhagen, sat for her photographic portrait in Stockholm in the 1850s in an embroidered black satin dress with white lace cuffs and collar, as well as an elaborate indoor bonnet (

Figure 11).

The Przibram family migrated to Vienna from Prague, and Baroness Schey moved from Trieste to Vienna after her wedding. Israel Barendt Melchior’s grandmother moved from Copenhagen to Stockholm, where she raised her family, and Matilda Salomons moved from Leiden to London. Salomon Josephson’s father left Prenzlau in Brandenburg to engage in business and settle in Stockholm. His wife was born in Copenhagen. Most nineteenth-century Jews had genealogical memories of migration.

3.3. Genealogical Memories of Migration and Dispersal

Many more Jewish albums, compared to non-Jewish albums, bring together dispersed relatives. In the nineteenth century and especially in the last two decades, millions of Jews migrated, either voluntarily or due to the force of circumstances, and their large families increasingly dissolved into nuclear family units. They moved away from their birthplace in order to seek new business opportunities, wed, or escape war and anti-Semitic decrees and violence. Many sent each other their latest portraits from their new residence, which collectors arranged in their albums.

The in-gathering of far-flung relatives between the covers of Jewish albums maintained the connectedness of a scattered family, sometimes over many decades. Although Amélie Crémieux lived in Paris, her album brought together members of her family in Vienna, Metz, and Strasbourg. The Ettinger album, as noted, gathered portraits from relatives spread out between Uman, Mezritch, Kiev, Bobruysk, Odessa, Kishinev, Riga, and Warsaw, within and beyond the Russian Empire. The Szulc family dispersed from Warsaw to Paris and Berlin; the Dreyfus couple had cousins in Antwerp, Amsterdam, and Paris. Albums of continental Jews show far more cross-border mobility than British and Scandinavian Jewish albums, which reflect the stability and dominance of the established moneyed class. Some albums show migrations from small towns to large urban centers, as in the case of the Ettingers.

The contents of Jewish portrait albums frequently embody genealogical memories of family migration. Even when most of their portraits are unnamed, albums bring together and visualize a multi-generational, physically dispersed, yet emotionally connected family, as presented in the following two examples of dispersed German Jews. The De Beer family from northern Germany emigrated in the nineteenth century, whereas the Freiberg and Deutsch families from the Rhineland fled the Nazis, and this album (and others, such as the Schames family album in the National Library of Israel, TMA 4833/1) became a valuable repository of family history following the trauma of the Shoah.

3.3.1. The De Beer Albums: Toward a Colonial Genealogy

When, in 1936, Augustus De Beer of Roslyn, Dunedin, deposited the two albums containing his family’s collection of photographic cards in the Toitū Settlers Museum, Otago, New Zealand (1936/118/2, 1936/118/3), he likely believed that these would contribute to the history of Jewish settlement in the region. The museum’s inventory records the albums as having belonged to Mr. and Mrs. Louis De Beer, the parents of Augustus. These two unannotated albums offer only a few names yet preserve the genealogical memories of Jewish families who emigrated from Emden and Hamburg. The portraits of family, friends, and celebrities convey the strong ties of the Antipodean immigrants with their Heimat, the German homeland. Of the 356 portraits in these albums, 61 were printed in German lands; 33 were printed in Australia, the first destination of these German Jews in the 1860s; and 111 were taken in the coastal town of Dunedin, New Zealand, where some members of the De Beer family settled. Whereas these albums bear witness to the maintenance of family bonds among first-generation colonialists in the Antipodes with their relatives back in Germany, the donation by Augustus to the local museum may also reflect the desire of the second generation to disengage from the family’s German past after the rise of the racist Nazi party in Germany.

The family’s genealogical narratives have lain dormant for almost a century. These albums have never been thoroughly researched or exhibited. The current research catalyzed the construction of the family’s genealogy. The probate of Mrs. Rosette De Beer, née Frank (b. Hamburg 1851–1927), widow of Louis De Beer, confirms that Augustus was one of the couple’s three surviving sons. The probate, state, cemetery, and newspaper archives provided further information that aided the construction of the forgotten genealogy of this colonial family. Louis De Beer’s obituary (Lake Wakatip Mail, 21 January 1887, p. 5) noted that he, Louis Solomon De Beer, was born in Emden. The Bendigo Advertiser, an Australian newspaper, reported his arrival on a ship from Rotterdam, together with his cousin, Joseph Van der Walde, on 13 December 1866, after four months at sea. Just over one year later, according to another Australian newspaper, The Age (21 February 1868, p. 4), he arrived in Adelaide, from where he was due to sail to Callao, a Peruvian port. However, Louis De Beer and his cousin settled in Queensland, New Zealand, where Louis worked as a draper and gained British citizenship in 1870. The following year, he married Rosette in Queensland, where their four sons and daughter were born: Solon, known as “Louis” (b. 1872–1934), Isidore Louis (1874–1920), Augustus Louis (1876–1954), Samuel Louis (1882–1957), and daughter Chanella/Schanette, known as “Nettie” (1879–1922). In 1902, Rosette and her daughter moved to Dunedin, where her sons were in business. The Southern Cemetery preserves the gravestones of Rosette and four of her children, inscribed in Hebrew and English.

The photographs from Emden and Hamburg show family, and possibly also friends, whom the De Beer couple left behind. The portraits appear in no obvious order in the two albums, although, occasionally, a few by the same photographer appear to be members of one family, taken on the same day. Two photographs sent from Hartford, Connecticut, show Martha Frank and her little brother Julius, a niece and nephew of Rosette’s. At least one from Emden shows Joseph van der Walde’s sister-in-law Emilie with her two eldest children. Most of the portraits date from the 1860s to the 1880s. Others, marked and unmarked, likely show the De Beer couple’s parents, aunts, uncles, siblings, and cousins who stayed behind.

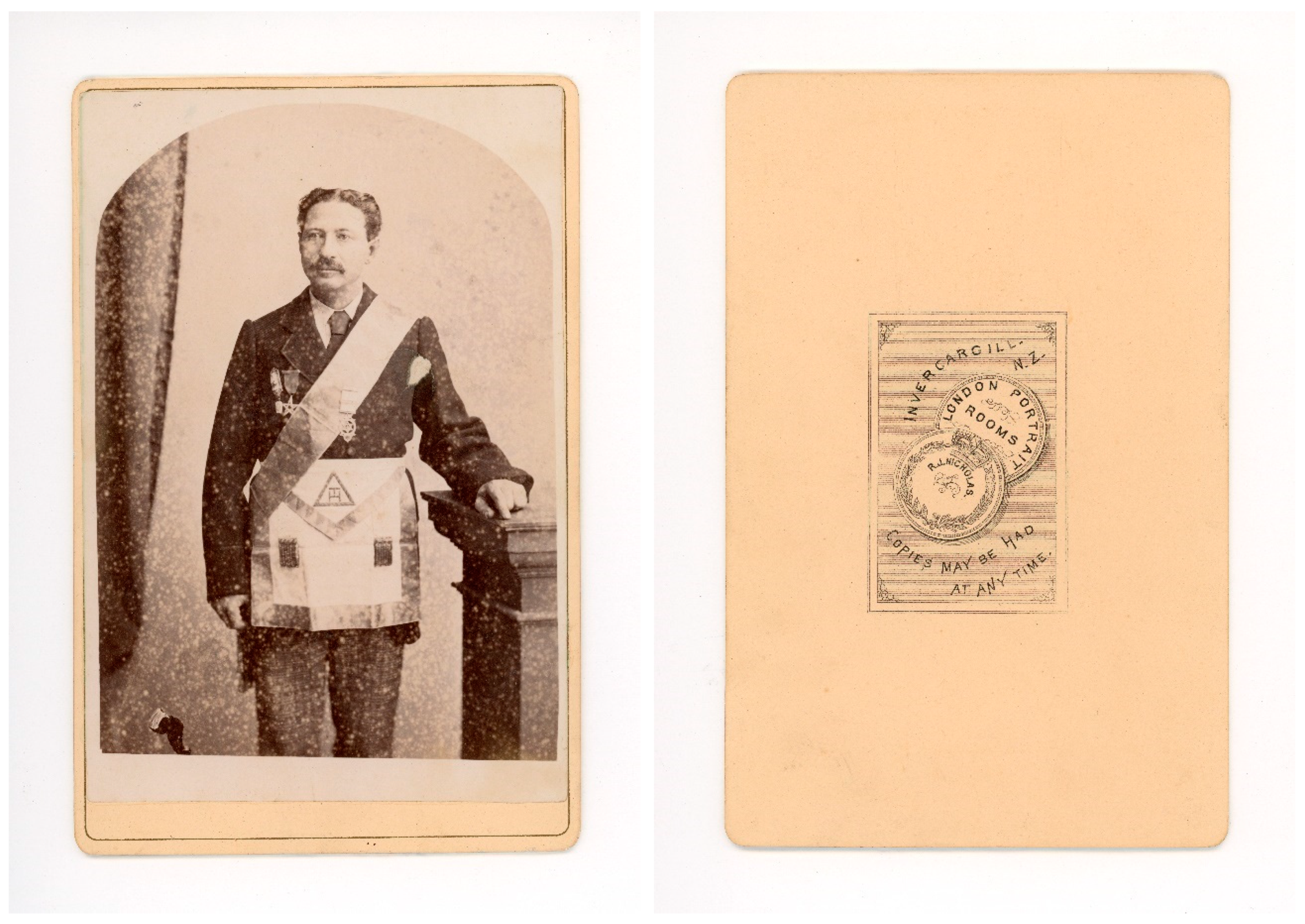

Louis’s brothers, Isaac/Isidore De Beer (1839–1910) and Salomon De Beer (1849–1917), also left Emden for the Antipodes. Isidore settled in Melbourne, and he and his family likely feature among the unnamed Melbourne portraits. In 1874, Salomon married Sophia Jacobs, the daughter of a Polish immigrant, in Christchurch, New Zealand. This couple settled in Dunedin, where Salomon was an active member of the Jewish community. They and their five children likely also feature among the many portraits taken in Dunedin. By 1888, they had moved to Melbourne and may appear in some of the Australian photographs. Obituaries in the local newspapers reveal that Louis and Joseph were active members of the Jewish community, and they and Salomon De Beer were elected Freemasons, where they contributed to the well-being of others in their town (

Figure 12).

The portraits from Australia show one evidently wealthy woman, with her hair covered in a net and an elaborate lace headdress on top. Others show Louis’s uncle, Samuel De Beer, and his family. Samuel was Louis’s youngest uncle, born in Emden in 1818, who emigrated to Australia in 1852, drawn by reports of the gold fields and new business opportunities. In Melbourne, where Samuel earned a living as a shipping agent, he married London-born Louisa Hart, who appears in one of the De Beer family albums, as do other members of her family. Samuel was likely instrumental in persuading at least four of his nephews to try their luck in Australia.

As Louis De Beer never lived in Dunedin, where the majority of the portraits were taken, and the albums contain only three portraits from Queenstown, it appears that the albums were arranged by Rosette, after she was widowed. She would have gathered together the family collections of loose photos, some brought over from Germany by the emigrants and others received in the mail over the years. This was her way of preserving and keeping together her vastly dispersed family. Her children apparently no longer felt the need to hold on to family memories when Augustus gave the albums to the Toitū Settlers Museum, set up in Dunedin in 1908, to document the lives of the early settlers and subsequent waves of migrants.

3.3.2. Rosa Freiberg’s Album: Dispersal before and after the Nazi Era

The album of Rosa Freiberg, née Deutsch (1860–1957), who was born in the small town of Ingenheim in the Rhine Palatinate, not far from Karlsruhe, reveals her family’s dispersal. Preserved in the Center for Jewish History in New York (AR 25181, ALB 187), this album contains portraits of six of Rosa’s siblings and many of her nephews and nieces, alongside some of her friends. Most of its 43 studio portraits were made in towns in the Rhine Palatinate in the 1880s and 1890s. However, three of her sisters left home in the late nineteenth century when they married: two sisters raised their families in Mainz (10 portraits from Mainz), and another did likewise in Alsace (6 portraits from Strasbourg), whereas her other siblings remained in the region of Ingenheim (14 portraits from nearby Landau). Ingenheim’s Jewish community dwindled from a maximum of 619 in 1856 to under 200 in 1900, when Rosa, her children, her mother, and three of her other siblings still lived there.

The album also displays 15 portraits in postcard format from the 1890s and early decades of the twentieth century, as well as 30 snapshots, including some taken in the USA after WW2. These are stuck over the pre-cut apertures on the album’s thick pages. A color snapshot dated 1963 was added to the album after Rosa had died. Rosa and three of her children, as well as one of her sisters and some of her nephews and nieces, escaped to the USA following the Nazi rise to power. One niece emigrated to Palestine.

The album, annotated by one of her grandchildren, gained genealogical significance following the Shoah, as it shows images of many members of Rosa’s family in the Rhineland prior to the Nazis’ arrival and preserves portraits of some whose lives were cut off by the Nazis, including her daughter Ida, born in Ingenheim in 1895; her brother Abraham/Albert, who died at the internment camp at Gurs, France; her niece Fanny Bader, née May, who perished at Auschwitz in 1944; and her cousin Hedwig Mayer, born in Steinbach, near Frankfurt, in 1883, who was murdered at Sobibor. It also displays Rosa’s nephew who died in infancy in Mainz in 1897 and another nephew, Alfred Blum, who was killed in Flanders in the first year of the First World War. A note on a snapshot taken in [Bad] Ragaz, 1912, picturing one of Rosa’s nieces, indicates that she found refuge in Argentina, presumably during the Nazi era. Other notes indicate a family that emigrated to Milwaukee.

Whereas the archive deposited in the Center of Jewish History by Rosa’s grandson, Werner Marx, includes genealogical material regarding the Marx and Freiberg families (

Marx 2003), he apparently did little research on the Deutsch family from Ingenheim. This album is more than just a collection of photographs; it contains valuable clues for investigation, including family names, relationships, and places of residence, starting points for radial research.

The albums discussed here, and many other Jewish albums, hold together dispersed families. They are living memorials to the departed. Unlike tombstones, these photographs bring genealogy to life.

4. Discussion

When Augustus De Beer and others donated their historical family albums to an institution, they had a sense of the importance of their heirlooms—a public importance that stretched beyond the family, even though most did not supply any genealogical or explanatory information. Similarly, when the Nazi authorities salvaged family photograph albums from deported Jews in Prague and elsewhere, they considered these would eventually have historical interest. This study set out to show that an active effort to research, discuss, and publish the albums’ historical narratives has given them genealogical meaning.

This study found that relatives who are alive today discovered hitherto unknown genealogical information via the research of their albums; they were able to visualize their ancestors within their nineteenth-century social networks and expand their knowledge about their extended family and its dispersal.

The studies of nineteenth-century albums mentioned in the introduction have placed album narratives in bigger, more universal narratives, including gender narratives, colonialism, and aspired identities. The Ettinger and Szulc-Bertillon albums have gender narratives, the De Beer albums have a colonial narrative, and the Crémieux album has an identity narrative. The genealogical study of named and unnamed albums pioneered here can be viewed in the framework of “connected histories,” a concept developed by Sanjay Subrahmanyam and applied to early modern Jewish history by David B. Ruderman (

Subrahmanyam 1999;

Ruderman 2010). Genealogy maps connectedness. The albums’ contents link nuclear families, conversations, spaces, and temporalities of the nineteenth- and early-twentieth-century Jewish bourgeoisie.

Commemoration provides another broad framework for unrelated spectators of such albums. Each album may serve as a potential “site of memory,” a site with a symbolic aura with a transmittable memorial function that bridges the past, present, and future, as envisaged by Pierre Nora and Jay Winter (

Nora 1989, p. 12;

Winter 2008, p. 62). Each spectator’s search for meaning in an album is crucial to its preservation as a site of commemoration. Descendants who donated their ancestral albums to institutions likely hoped that these visual archives would somehow become sites of memory, beyond family memory and genealogy—sites of Jewish memory or, in the case of De Beer, colonial memory. The albums discussed here contain images capable of engaging the public in questioning the backstories of their contents and imagining the lives of the people portrayed. How do they differ from one’s own ancestors and their backstories? In what ways, if any, are their stories Jewish stories? What happened to these families in the mid-twentieth century?

Although trauma and loss are not a central theme in this study, for Ettinger’s relatives in Israel today and for the descendants of Berthe Dreyfus, the Burchardt and Schames families, and Rosa Freiberg, the trauma and murders during the Second World War (WW2) shattered and scarred their family history. The study of albums for genealogical insights gave rise to “postmemorial work,” to use Marianne Hirsch’s concept. The reactivated memory of distant family history reconnected the extended Ginzberg family, as well as Louise Dessaivre, to the lives of their ancestors before these were shattered during WW2 in Eastern Europe and in France, respectively. Both of these families had kept their albums within the family. In the case of institutionalized albums, the descendants, if any are still alive, forwent engaging in postmemorial work on their own families.

The case studies presented here, some in more detail than others, show that it is possible to construct or discover additions to a family tree and/or reactivate the micro-histories and collective memories of Jewish families from some nineteenth-century portrait albums. These sources have advantages and disadvantages for researchers of family history.

4.1. Advantages: Context