4.1. Japheth

The genealogy of Japheth is made up of two units of seven nations. The name Japheth may reflect the name Iapetos, the son of Uranus (Sky) and Gea (Earth), one of the Titans of Greek mythology. The sons of Japheth number a group of nations located from the northeast of the Fertile Crescent (Madai) to the Greek islands (Javan = Ionia) in the west, including peoples who resided in Anatolia.

Gomer, according to most scholars, is identified with the Assyrian Gimirrai, the Cimmerians in classical sources. They were an Indo-European people who resided north of the Black Sea and who by the end of the eighth century BCE relocated to Asia Minor. In Ezekiel 38:6, Gomer is mentioned in league with Gog king of Magog. Gomer’s progeny is Ashkenaz, which has been identified with the Assyrian Ashquza, i.e., the Scythians. Jeremiah describes how they joined with Ararat, the Mannaens, and the Medes in an attack on the Neo-Babylonian empire (51:27–28). According to Herodotus, they even advanced on Egypt. From the Greek name Scythopolis, we can infer that some had settled in Beth Shean.

Riphath is unknown. In the parallel version in I Chronicles 1:6 the name is written Diphath. Togarmah, however, is documented in the fourteenth century BCE Hittite sources, where it is called Tegarama, as well as in Assyrian sources as Til-Garimum, which fell before Sargon II and Sennacherib. It was located north of Harran and Carchemish on the Euphrates River. Ezekiel identified it as a supplier of horses and mules in the Tyrian mercantile empire (Ezekiel 27:14; 38:6). The expanded name Beth-Togarma, as used by Ezekiel, may indicate that this kingdom fell under Aramean influence, as did other north Syrian neo-Hittite peoples.

The second son of Japheth is Magog. This is the land of Gog (Ezekiel 38:2; 39:6), who is identified by most scholars with Gyges of Lydia in western Asia Minor. According to Herodotus (Bk. 1, 8–14), he founded the local dynasty in the early seventh century BCE

Madai refers to the Medes, an Indo-Iranian people who dwelt to the east of Mesopotamia. During the seventh century BCE, they reached the height of their political power and contributed to the fall of the Neo-Assyrian empire and later, in the sixth century, to the weakening of the Neo-Babylonian empire (see Isaiah 13; 21:1–10; Jeremiah 25:25). They were finally conquered by the Persians under Cyrus the Great in 550 BCE

Javan represents Ionia, the area around the Aegean Sea, the home of the ancient Greeks, and is mentioned already in the eighth and seventh centuries in Assyrian documents as Iaman. Ezekiel refers to Javan along with Tubal and Meshesh as slave traders (Ezekiel 27:13). An echo of trade in Judean captives in cooperation with the Phoenicians and Philistines is found in Joel 4:6.

The four sons of Javan are Elishah, Tarshish, Kittim, and Dodanim, ordered in two pairs. The first pair are place names, the second, names of people in the plural. Elishah is identified with Alashiya, mentioned in Hittite, Akkadian, Egyptian, and Ugaritic texts as well as Ezekiel 27:7 as “the coasts of Elishah”, identified as Cyprus or a part thereof.

Tarshish has been identified with sites as far apart as Tarsus in Asia Minor and Tartessos in Spain. The name appears in the ninth century BCE Nora inscription from Sardinia. Possibly, it was a common name for far-off Phoenician colonies where different metals like silver, iron, tin, and lead could be bartered (Ezekiel 27:12) or refined (Jeremiah 10:9), as

Albright (

1944, pp. 254–55) has suggested. In any case, it lent its name to worthy sea-going vessels that set sail both in the Mediterranean and Red Seas (e.g., I Kings 10:22; 22:49; Isaiah 23:1, 10, 14). Tarshish is mentioned in conjunction with Pul (Put? Cf. Ezekiel 27:10), Lydia, Meshech, Tubal, and Javan (Isaiah 66:19) and with Sheba and Dedan (Ezekiel 38:1; see also II Chronicles 20:36–37).

Kittim is commonly identified with the Phoenician colony of Kt(y), Greek Kition, modern Larnaka on Cyprus. They traded in boxwood furnishings inlaid with ivory (Ezekiel 27:6). Kittian mercenaries are mentioned in the ostraca from Arad, where they were stationed in the defense of the southern border of the late Judean monarchy.

The identification of Dodanim is an ancient crux with no ready solution. The parallel text in Chronicles 1:7, as well as the Septuagint and Samaritan versions of the Torah, read Rodanim, identified with the Isle of Rhodes. However, this may be no more than an interpretive reading as the Chronicles has done with the Mash/Meshech. Others have explained the name as a biform or a mistake for the Danuna mentioned for the first time in the El Amana letter number 151 (ca. 1360 BCE). The Dananim are known from the Azitawada and Kilamuwa inscriptions (9th-8th centuries BCE), the former being the ruler of that people residing in Adana, in present-day southern Turkey. In Assyrian sources, the island of Cyprus is called Yadnana, a reflex of this same name. This line of interpretation would place the Dodanim in close proximity to Elishah and Kittim.

Tubal and Meshech are a pair mentioned together in Ezekiel 27:13; 32:26; 38:2–3; 39:1 either with Javan or with Magog (see also Isaiah 66:19) and were located in eastern Asia Minor near Cilicia. They are mentioned together in Assyrian sources as Tabal and Mus(h)ku. Herodotus mentioned two neighboring peoples, Tibaroi and Moschoi, who lived on the southern shore of the Black Sea. Their geographic proximity and close political ties probably made them inseparable in the eyes of the Israelites, Assyrians, and Greeks.

Tiras, the youngest of the sons of Japheth, has been identified with one of the Sea Peoples called by the Egyptians Twrwsha. Tiras may also be reflected in the Greek Tyrsenoi, that is, the ancient Etruscans, who, according to Herodotus, migrated from Lydia in Asia Minor to Italy.

4.2. Ham

The second son of Noah to appear in the Table of Nations is Ham. However, according to Genesis 9:24, he seems to be the youngest.

Ham’s four sons are Kush, Mizraim (Egypt), Put, and Canaan. Kush’s genealogy gives him five sons and two grandsons, totaling seven (see Japheth above). Kush is Nubia, the land to the south of Egypt, beyond the first cataract at Aswan (Ezekiel 29:10). The name has come to stand generally for Africans residing on the southern extremity of the biblical world. The Septuagint occasionally translates the name Kush as Ethiopia. The sons of Kush, to the point that they can be identified, are found on the African and Asiatic sides of the Red Sea.

Complicating the picture is the similarity of the name Kush to other nations in the biblical world. The Kwshw are mentioned in the nineteenth century BCE Egyptian Execration Texts and probably refer to a West Semitic tribe living in the Negeb or in Seir (ancient Edom). In the Bible they are called Kush (II Chronicles 14:8) or Kushan, in league with Midian (Habakuk 3:7). It is probably in this context that we should understand the reference to Moses’s Kushite wife (Numbers 12:1), who was none other than the Midianite Zipporah.

Furthermore, between the eighteenth and the fourteenth centuries BCE, the Kassites, Kushshu in the Nuzi documents and Kossaios in classical Greek, ruled Babylon and were in direct contact with Egypt and Canaan. At the end of this period, the Canaanites in their correspondence with the Egyptian court refer on various occasions to the African Kushite mercenary forces by the name Kashi (EI Amarna letters 127, 131, and others). On the basis of homonymous association, one can better understand the intentional identification of apparently disparate elements as African peoples, Nimrod the Mesopotamian, and South Arabian sites (Sheba and Dedan) as all related to Kush.

Seba was the oldest son of Kush. It is often assumed that this is the South Arabian form of Hebrew Sheba. However, the several biblical references to this name in conjunction with Egypt and Kush (Isaiah 43:3; 45:14) and alongside Sheba, as in this genealogy as well as in Psalms 72:10, would indicate that this was an independent kingdom probably in Africa.

Havilah is mentioned twice in connection with the territories of Ishmael and Amalek, somewhere on the southern boundary of Israel (Genesis 25:18; I Samuel 15:7). Since Havilah reappears with Sheba in Joktan’s genealogy (Genesis 10:29), it must be located in the Arabian Peninsula. On the other hand, it is mentioned in Genesis 2:11 as the land around which flows the Pishon, one of the four great rivers that flowed from the Garden of Eden; there one finds gold, bdellium, and lapis lazuli. Note that the Gihon, the second river, encircles the land of Kush. The connection of these remote riverine areas (see Isaiah 18:1–2) with Eden in Mesopotamia assumes a different conception of world geography than our own.

Sabta (Septuagint: Sabata) has no agreed-upon identification. However, of all the various suggestions in Africa and in the Arabian Peninsula, perhaps the most suitable would be the city of Sabota, the ancient capital of the South Arabian kingdom of Hazarmaveth, 420 km northeast of Aden. Sabbeca remains unidentified.

Raamah has been identified, though not without linguistic difficulties, with the South Arabian city of Rgmt located in the district of Majran. This area lies between that of Dedan to the north and the kingdom of Sheba to the southeast.

Independent of this name-list of Afro-Arabian sons of Kush is the passage on Nimrod (vss. 8–12). Needless to say, this section has raised many problems as far as the suggested connection between Kush and Mesopotamia and the introduction of narrative between genealogies. Furthermore, the identity of Nimrod and a few of the cities he established remains in doubt.

Regarding a Kushite Nimrod, as mentioned above, there seems to be an underlying homophonous association between Kush and the Cassites, who controlled southern Mesopotamia for several hundred years during the late second millennium BCE This identification was intentional in the present context. Certainly, from the biblical point of view, the Kushites lived in Babylon with the rest of Noah’s descendants before the Dispersion (Genesis 11:1–9). The Nimrod story has a structural function in the Table, for by adding his name to the number of nations listed in the fixed genealogies, plus Noah’s three sons, the sum of seventy is attained. Then again, the passage gives details about an ancient monarch and about the beginning of post-diluvian urban civilization. Various scholarly attempts to identify Nimrod with an historical Mesopotamian king or with a mythological god have been suggested (

Levin 2002). Perhaps Nimrod is a composite figure of the ideal Mesopotamian king. In any case, Nimrod was the subject of Israelite legend and prophecy (Genesis 10:9; Micah 5:5).

The “mainstays” (

Speiser 1964) of Nimrod’s kingdom were the ancient capitals of Babylon, Erech and Accad, which, along with Sippar and Nippur in local Mesopotamian tradition, became the major centers of post- diluvian urban society. The last named Calneh is unknown from Mesopotamia, though an inappropriate north Syrian namesake is well documented (e.g., Amos 6:2; Isaiah 10:9).

Albright (

1944), however, has convincedly suggested that the word be vocalized

kullanah “all of them (i.e., the above three cities)” to be located in the Land of Shinar, ancient Sumer.

Nimrod’s building activity continued into northern Assyria, emphasizing that area’s cultural debt to Sumer and Babylon in the south. Two of the four listed cities, Calah and Nineveh, are well-known capitals of Assyria. The other two, Rehoboth-Ir and Resen, are unknown and are probably descriptive phrases of the two better-known cities or parts thereof (

Hurowitz 2008). Calah was the larger and more impressive city until it was supplanted by Nineveh at the end of the eighth century. It is noteworthy that the modern name of Calah is Nimrud.

Mizraim “fathered” seven nations, all written in the plural, who were either part of Egypt or dependent upon her (

Görg 2000). Cassuto has pointed out that the order of these seven follows the progression from a simple two-radical stem “Lud” to a three- “Lahab” and then four-letter stem Patrus.

The Ludim are generally identified with Lydia in Asia Minor. However, an African location is preferred in light of Jeremiah’s and Ezekial’s prophecies to the gentiles, where Lud is mentioned along with Put (Jeremiah 46:9) and Kush (Ezekiel 30:5) as archers serving Egypt. Anamim and especially Lehabim have been located in Cyrenaica or ancient Libya.

Patrusim is clearly the identifiable province of Upper Egypt (Isaiah 11:11, Jeremiah 44:1; 15; Ezekiel 29:14; 30:14). Naphtuhim has been understood as referring to the north land, i.e., Lower Egypt. The name has a Hebrew plural ending attached to what seems to be a preserved Egyptian term

n-Ptaḥ, i.e., “belonging to the god Ptaḥ” (

Görg 2000, p. 29). Ptaḥ’s sacred city was Memphis south of the Delta, which was one of the ancient capitals of Egypt. Its Egyptian name was

Ḥut-ka-Ptaḥ, i.e., “The abode of the soul of Ptaḥ”. When the Greeks arrived, they could not pronounce the gutturals, so they called that area “Aigyptos”, which became the European name for the entire country.

The Kasluhim remain unidentified. The mention of the Philistines as coming from their land is also difficult, since the Philistines are associated in the Bible with the last members of this list, i.e., Caphtor (e.g., Kftyw, Akkadian: Kaptara Ugaritic: KPTR), ancient Crete (Amos 9:73; Jeremiah 47:4). Note that the Philistines or a part thereof are also called Cretans (Ezekiel 25:16; Zephania 2:5, Cf. also II Samuel 8:18). An interesting reference to the Caphtorim is found in Deuteronomy 2:23, where they are described as supplanting the native Avvim, who dwelt in open settlements probably to the south of Gaza (see also Joshua 13:3) bordering the land of Egypt.

There is a difference of opinion regarding the location of Put, Ham’s second son. Some identify it with Punt in the Horn of Africa (Somalia), while most recent commentators, following the ancient Greek and Latin translations, tend to identify Put with Libya (see also Nahum 3:9 and Josephus, Antiquities 1:6:132).

The list of the Canaanite nations is a literary unit in its own right. It has been studied by

Tomoo Ishida (

1979) along with parallel two- (Genesis 13:7; 34:30; etc.), five- (Exodus 13:5; etc.), six- (Exodus 3:8; 17; 23:23; 33:2, etc.), seven- (Deuteronomy 7:1; Joshua 3:10; 24:11), eight- (Ezekiel 9:1), and ten- (Genesis 15:19–21) name lists of indigenous Canaanites. Ishida noted the inner structure of these lists presents three documented designations for the native population: Canaanites, Hittites, or Amorites, and three or four of the lesser-known ethnic groups: Perizites, Hivites, Jebusites, and Girgashites. He assumed a basic six-name list that is sometimes expanded into seven. The totality of the indigenous population can be summarized by mentioning one of the major and one of the minor peoples, e.g., Canaanites and Perizites (Genesis 13:7; 34:30; Judges 1:4–5). As is the case in Genesis 10, the name-list is sometimes expanded, as in Ezra 9:1, adding three non-Canaanite nations: Ammonites, Moabites, and Egyptians, or in Genesis 15:19, adding the Kenites, Kenizites, Kadmonites, and Rephites.

The sons of Canaan in the Table of Nations fall into two clearly discernable groups of six indigenous nations, including the eponymic Canaan, Heth, the Jebusites, the Amorites, the Girgashites, and the Hivites, and six Phoenician–Syrian kingdoms including Sidon and the coastal city states of Arka(ta), Siannu, Arwad and Sumur plus the neo-Hittite kingdom of Hamath in the Syrian hinterland. Canaan, Sidon, and Heth are proper names; the others are adjectival forms. Their order seems to be based on a chiastic relationship between Sidon and the other minor kingdoms, and Heth and the native peoples of the Land of Canaan. It is possible that underlying this order is the assumption that Sidon “the first born” should be considered the “father” of the northern city-states, while Heth is the “father” of the southern indigenous nations (

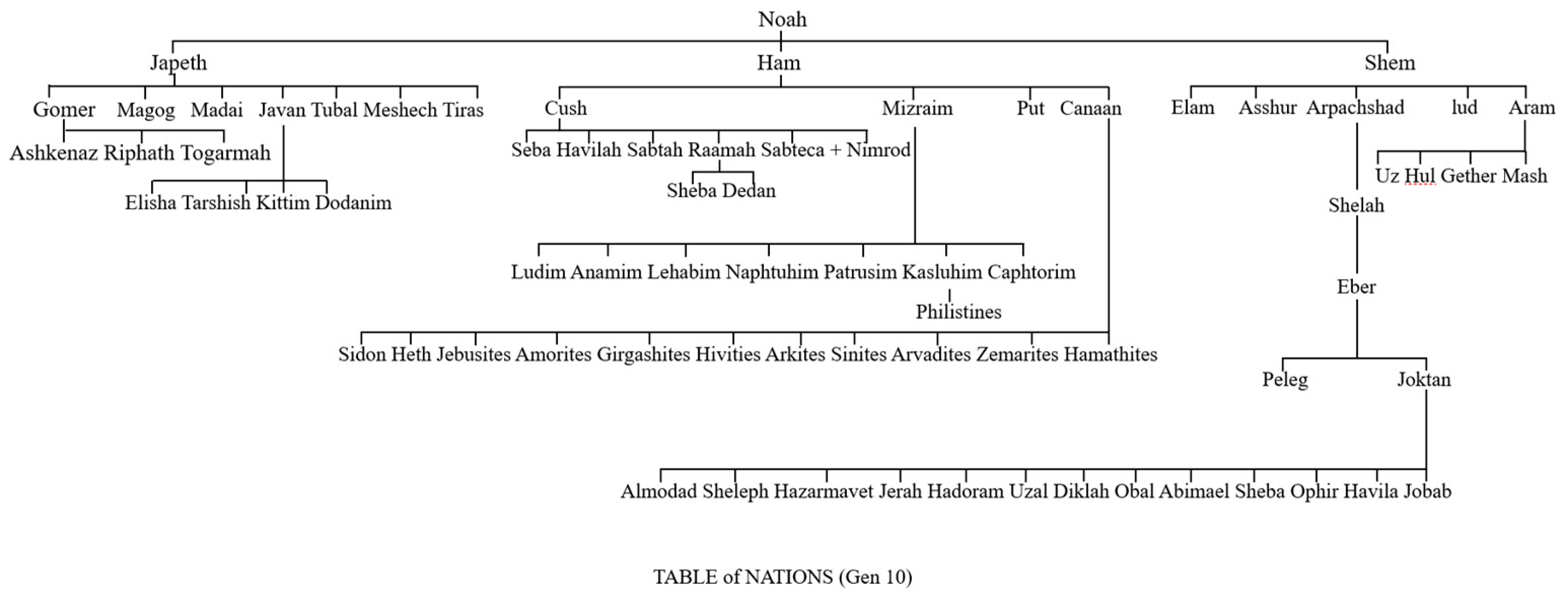

Figure 1).

At this point in the Table of Nations, a geographic aside, describing the borders of the land of Canaan, is added. The starting point is again Sidon in the north, probably referring to the kingdom of Sidon, including the Phoenician coast. The southwestern corner of Canaan was the land of Gerar and city of Gaza, probably indicating that at this time Nahal Besor (Wadi Gaza) was identified as the Brook of Egypt. This would be another case of “anticipation”, i.e., a literary technique of introducing seemingly parenthetical information early in the book that will become significant later in the narration (

Sarna 1981). It seems to me that noting such a boundary line here illuminates the later description of Jacob’s funeral cortege, which encamped near Abel-Mizraim, as viewed by the Canaanites (Gen 50: 10–11) (

Demsky 1993).

8 Furthermore, the southern border extended eastward from Gerar through Beersheba and Arad (Numbers 21:1; 33:40) to the five cities of the plains south of the Dead Sea: Sodom, Gomorrah, Admah, Seboim, and Lasha’ (also called Bela’ or Zoar—Genesis 14:8). This border is the geographic background of the patriarchal journeys of Abraham and Isaac that will enfold in this area of the Promised Land (Genesis 19:28; 20:1).

4.3. Shem

Of the five sons of Shem, only two are given in detail: Aram, the youngest, and Arpachshad, the third. The four sons of Aram are Uz, Hul, Getter, and Mash, of whom almost nothing of substance is known. These four names may be ancient tribal or place names (see Genesis 22:21). Uz might be connected with that land mentioned in Job 1:1 or, less likely, with the Horite namesake in Genesis 36:28 (see Lamentations 4:21). However, this archaic name, as well as Buz (Genesis 22:21), continues to appear in Jeremiah (25:20, 23) as a designation for close and distant neighbors. Mash might be a geographic term for some part of the Lebanon mentioned in the story of Gilgamesh (Table IX, col. 2: lines 1–2). Later versions and even the parallel in Chronicles attempt to give a corrected reading on the basis of a better-known name (LXX, Chronicles: Meshech; Samaritan Torah: Massa). The position of Aram as the youngest son of Shem as compared to the Nahor name-list reflects the rising importance of the Arameans by the end of the second millennium BCE in the constellation of peoples around the Fertile Crescent.

At this point in the chapter, several of Abraham’s ancestors are mentioned. Moving from ethnic and geographic names to personalities, the genealogy changes from a segmented to a linear form: Arpachshad, Shelah, and Eber.

The name Arpachshad still defies explanation. The second half of the name may be a reflex of Chesed (Genesis 22:22) and represents the home of the Chaldeans, from where the Patriarchs sojourned (Genesis 11:31). Eber has been cited above in one of the designations of Shem, “the father of all the children of Eber”. He is the eponymous ancestor of the Hebrews, who include the Israelites.

Peleg and Joktan are Eber’s sons. The latter is the eponymous father of the last segmented genealogy in the Table, including thirteen (south) Arabian tribes and kingdoms. The number is problematic and has been viewed as either an expansion of an original twelve-son list or a fourteen-unit name-list including Joktan. However, it might have been conceived to balance the other above-mentioned thirteen offspring of Shem.

The identification of most of the names is uncertain. However, Hazarmaut and Sheba are two known South Arabian kingdoms and Ophir, the source of high-quality gold, was probably located on the east coast of Africa. Uzal may be the same as Meuzal, mentioned in Ezekiel 27:19 as trading in polished iron, cassia, and calamus.

Chapter eleven, verses 10–32 presents a ten-generation linear genealogy from Shem down to Abraham, giving biographical data reminiscent of chapter five. This list reconnects the reader to the narrative.

By focusing on the so-called Table of Nations in Genesis 10, I have tried to show how genealogy became a literary genre in the Bible. Noted were such literary devices as chiasms, anticipation, and symbolic numbers, which enhance the message of these sources. Furthermore, introducing linear genealogies with a structural depth of ten generations was a means of neatly summarizing earlier generations without narrative. On the other hand, segmented genealogies placed at transitional junctures in the narrative served as pauses in the overall story.