Abstract

Migration has become an inescapable reality affecting South African families, extending its impact far beyond the immigrant to those staying behind. The geographical separation of parents from their adult children and grandchildren significantly alters family dynamics, creating logistical and emotional challenges. Participants in this study reveal a deeply felt need to physically reconnect with their loved ones, emphasizing the emotional solace derived from in-person interactions. The enduring parent-child bond motivates family members to find meaningful ways to maintain their connections across vast distances and differing time zones. Transnational visits serve as a crucial lifeline, enabling parents to experience their children’s new environments and strengthen bonds with their grandchildren. This article draws upon ongoing qualitative research exploring the lived experiences of South African parents with emigrant children and grandchildren, focusing on the barriers that hinder these transnational visits. It focusses on parents’ unique experiences travelling to visit their emigrant children, rather than return visits. While they are essential for sustaining familial bonds, visits are deeply layered experiences, shaped by financial constraints, the logistical complexities of long-distance travel and the emotional weight of farewells. These factors have the potential to render visits infrequent and emotionally complex.

1. Introduction

In today’s globalised world, emigration profoundly impacts South African families. A steady stream of citizens continues to leave the country to work and live abroad, contributing to a growing diaspora (Mabandla et al. 2022). While the economic implications of this exodus are well-documented, the social and psychological effects on those left behind remain underexplored (Schröder-Butterfill 2021; Ferreira and Carbonatto 2023). This aligns with the broader trend in migration research, which predominantly focuses on migrants while often overlooking the experiences of those who remain in their home country (Schuler et al. 2022). Migration is not a one-sided phenomenon; it deeply affects individuals on both sides of the transnational divide.

Maintaining intergenerational connections within transnational families presents significant challenges, as emigration has the potential to weaken bonds and disrupt relationships (Portes and Rumbaut 2001; Miah 2023). For South African parents, emigration reshapes their relationships not only with their children but also with their grandchildren. Despite these disruptions, the parent-child bond mostly endures, supported by early social connections that form a foundation for lasting affection (Moss et al. 1985; Climo 1992).

Maintaining frequent and meaningful contact with loved ones is crucial for parents left behind when navigating geographic separation. Marchetti-Mercer et al. (2021) highlight the natural desire of families separated by migration to stay connected. Advances in communication technologies and air travel have made it easier for transnational families to maintain connections (Baldassar 2007b; Marchetti-Mercer et al. 2021). While virtual co-presence fosters emotional closeness across distances, physical visits offer the irreplaceable experience of embodied connection (Baldassar and Wilding 2020). These innovations illustrate the resilience of transnational families in overcoming physical separation and cultural adjustment challenges.

Visits are pivotal in maintaining familial and cultural ties across borders (Carling 2002; Janta et al. 2015). These visits, whether initiated by migrants returning to their homeland or by family members travelling abroad, are central to the human dynamics of transnationalism. This study focuses on “reverse visits”, where South African parents travel abroad to visit their emigrant children. Such visits are essential for maintaining intergenerational relationships, yet they tend to occur less frequently than desired, due to various constraints and challenges.

Given this context, the objective of this study is to explore the meaning and value that South African parents attach to transnational visits as they travel abroad to reconnect with their emigrant children. While these visits hold significant emotional and relational importance, they are hindered by barriers such as financial limitations, the challenges of long-haul travel, and the emotional weight of farewells. By uncovering these underlying factors, this research aims to provide a deeper understanding of the complexities of transnational visits and their significance in sustaining familial bonds across geographic distances.

A South African Perspective on Emigration

Emigration and immigration remain contentious issues in South Africa (Kaplan and Höppli 2017). Its influence extends beyond economic factors, shaping social and cultural landscapes. As highlighted by South Africa’s Statistician-General, Risenga Maluleke, migration is a highly debated topic in contemporary South Africa, often sparking passionate opinions from various perspectives (Lemaitre 2005).

Globally, and within South Africa, available data often fail to capture the scale and complexity of migration patterns (Lemaitre 2005; Höppli 2014). Current emigration statistics are sourced from Stats SA (2018), the United Nations International Migrant Stock database, and National Statistics Offices (NSOs) of foreign countries (Buckham 2019). While informative, these sources often lack the detail needed to understand migration nuances fully.

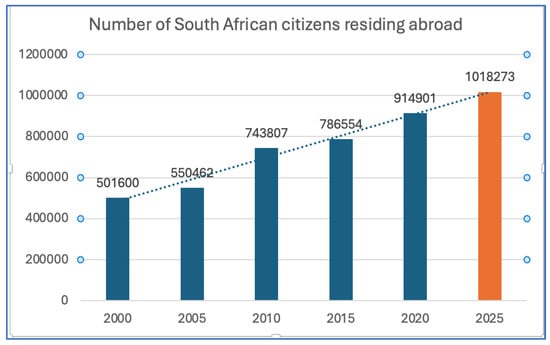

Statistics South Africa (2024) published the inaugural Migration Profile Report for South Africa: A Country Profile 2023, which provides a detailed analysis of migration trends, migrant characteristics, and the socio-economic effects of migration. It also presents data on South African-born citizens living abroad since 2000. The accompanying graph adapted by the author and a data analyst, forecasts trends for 2025 based on the original data.

As illustrated in Figure 1, over one million South Africans-approximately 1.6% of the total population of 63 million (Statistics South Africa 2023)-currently live abroad. This reflects a significant emigration trend with lasting impacts for the economy, workforce, and family dynamics.

Figure 1.

Number of South African citizens residing abroad, projected to 2025.

Globally, migration is fuelled by disparities in economic opportunities and living standards between developed and developing nations, alongside political unrest and economic stagnation in source countries (Isaksen et al. 2008). The decision to emigrate is multifaceted and multi-layered, involving numerous factors that justify such a life-changing choice (Ferreira and Carbonatto 2023).

Key motivations for South Africans include a fraught political climate, high crime rates, and the mobility of highly skilled individuals (Van Rooyen 2000). Fourie (2018) further identifies factors such as poor economic growth, concerns about safety and security, land redistribution debates, potential constitutional changes, and corruption in both public and private sectors. The exodus of skilled professionals, often referred to as the “brain drain”, poses serious concerns for South Africa’s long-term economic growth and workforce sustainability (Crush 2000).

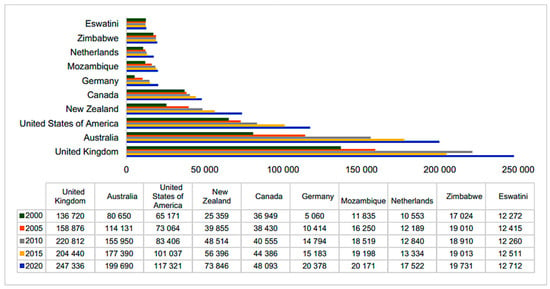

The top ten destination countries for South African expatriates from the Migration Profile Report (Statistics South Africa 2024) are shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2.

Top ten receiving countries of South African citizens residing abroad.

A significant trend in recent years is the emigration of younger South Africans, primarily seeking better employment opportunities and improved living conditions in developed countries (Thorne 2024). The majority relocate to the United Kingdom, followed by Australia, the United States, and New Zealand (Fraser 2024).

As illustrated in Figure 2, this trend continues to reshape South Africa’s population dynamics. The geographic distance of these destinations complicates transnational family relationships, making it challenging to maintain close bonds across continents (Ferreira 2024).

2. Transnational Families

In South Africa, family structures are deeply rooted in cultural heritage and history, yet they have evolved significantly (Lubbe 2007), especially with the rise of transnational families due to emigration. Transnational families, as defined by Bryceson and Vuorela (2002), are those who live apart for significant periods yet sustain a shared sense of welfare and unity—what they term “familyhood”—across national borders. Glick Schiller et al. (1992, p. 1) describe transnationalism as “the process by which immigrants build social fields that link together their country of origin and their country of settlement”, highlighting the multidimensional and interconnected nature of these connections.

Emigration is a systemic and enduring phenomenon. Goldin (2002, p. 4) observes that “migration is one of the most enduring themes of human history. It is one of the most drastic life changes and transitions an individual can face”. The impact of this transition extends beyond the emigrant, profoundly affecting those left behind—particularly parents, who face significant life changes marked by the loss of relationships as they were previously known, not only with their child(ren) but often with their grandchild(ren) as well. These parents, often referred to as “left behind”, face the complexities of managing relationships and care at a distance (Baldassar 2007a; Knodel and Saengtienchai 2007). The impacts of migration extend across entire family systems, necessitating that members adjust to new roles and dynamics influenced by geographic separation, as highlighted by Marchetti-Mercer (2009).

The transformative nature of emigration affects the parents of migrants, termed the “zero generation” by Wyss and Nedelcu (2018). The unique emotional void experienced by parents due to the absence of daily interactions with their children and grandchildren is emphasised by Aviram-Freedman (2005). This persistent longing for closeness and belonging felt by the “zero generation” remains inadequately addressed by technology-mediated communication alone. Feelings of loss, loneliness, and isolation are prevalent among left-behind parents (King and Vullnetari 2006; Knodel and Saengtienchai 2007; Miltiades 2002).

Boss (1991, 1993, 1999) introduces the concept of ambiguous loss to illustrate the complex and unresolved experiences of loss encountered by those left behind, particularly in the context of emigration. This type of loss is ongoing and difficult to define, leaving families in a state of uncertainty. When a child emigrates, the family left behind embarks on a lifelong journey of emotional adjustment and healing. This journey is marked by an enduring emotional struggle, as the separation does not offer closure but rather a continuous negotiation of connection and loss (Boss 2004).

Migration necessitates reimagining traditional family practices. Svašek (2008) and Walsh (2018) observe that transnational families develop new ways to express care and support, navigating emotional, cultural, and social boundaries. The resilience of transnational families lies in their ability to adapt, reconstitute, and redefine their relationships over time.

Information and communication technology (ICT) plays a vital role in sustaining these relationships. Digital communication technologies make emigration more acceptable by facilitating communication and allowing families to renegotiate their roles and intimacy across distances (Levitt and Schiller 2004). Baldassar (2008) highlights how ICT fosters a sense of “co-presence”, enabling families to maintain meaningful connections despite physical separation. Additionally, the accessibility of international travel supports face-to-face visits, which remain crucial for strengthening familial bonds (Steiner and Wanner 2015). ICT and transnational visits serve as lifelines, offering ways to negotiate intimacy and maintain unity despite the distance.

3. Transnational Visits

Migration is not a singular affair; it is a shared experience involving those who leave, those who remain, and those who move between worlds, shaping generations to come (Falicov 2005). As Falicov (2005, p. 399) poignantly asks, “If home is where the heart is, and one’s heart is with one’s family, language, and country, what happens when your family, language, and culture occupy two different worlds?” This question captures the profound dual belonging experienced by emigrants scattered across borders yet striving to maintain ties with their origins. Technological advancements, as highlighted by Falicov (2007), enable emigrants to maintain emotional connections with their families and home countries despite geographical separation.

While technological advancements have enabled virtual connections among families separated by migration, they cannot replace the unique emotional and physical interactions offered by in-person visits (Baldassar and Wilding 2020). Baldassar (2007a) highlights the embodied need to witness and experience the spaces where loved ones reside personally. Urry (2002) conceptualizes these visits as “facing the place”, emphasising the importance of physically experiencing locations where loved ones reside, from walking through neighbourhoods to engaging in daily routines. Visits are essential for fostering familial bonds, allowing family members to directly observe and engage with each other’s lived realities.

For transnational families, in-person visits allow parents and children to revive and nurture attachments. Visits play a critical role in maintaining familial bonds, allowing families to share moments of emotional closeness, engage in mutual care, and reaffirm their interconnectedness across physical distances. Baldassar (2007b) found that these interactions are particularly vital for forming and strengthening bonds with grandchildren, ensuring that family members feel they genuinely “know” each other. They complement virtual interactions, enabling a deeper, embodied form of connection that technology alone cannot provide.

For parents, visiting their children’s homes bridges the gap between imagined spaces created through video calls and the lived realities of those environments (Marchetti-Mercer et al. 2021). This embodied presence fulfils a deep need to reaffirm familial connections and gain a tangible understanding of their loved ones’ lives abroad. Such experiences foster deeper emotional connections, enabling families to share closeness, engage in mutual care, and observe unspoken cues such as body language and tone—elements foundational to sustaining relationships (Urry 2003).

Marchetti-Mercer et al. (2021) along with King and Vullnetari (2006) and Plaza (2000), identify two main types of transnational visits: outward visits (or “other-way” visits) and return visits. Outward visits refer to those undertaken by family members left behind in the homeland who travel to destination countries to visit their emigrant relatives. Return visits, on the other hand, are visits made by emigrants who return to their homeland to reconnect with family and friends. Each of these visit types serves unique functions in sustaining familial relationships across borders, reflecting the dynamic and multifaceted nature of transnational family interactions.

While transnational visits are often celebrated for their emotional and symbolic significance, they are not without challenges. According to Climo (1988), challenges involve intricate negotiations and detailed planning, with the duration of visits often dictated by work commitments and schedules of both parents and their emigrant children, who must carefully balance obligations to enable meaningful visits. These encounters demand substantial time, financial resources, and emotional investment. Tensions frequently arise over who should travel and who should host, with such responsibilities creating logistical and emotional strain (Janta et al. 2015).

Existing literature emphasizes the benefits and emotional significance of transnational visits, highlighting their role in maintaining familial bonds and fostering meaningful connections across distances. However, these visits are often hindered by significant barriers, including the challenge of balancing work, family responsibilities, and financial constraints (Climo 1988). For South African long-haul flights, multiple transit points, and high travel costs particularly to destinations like Canada and Australia necessitate extended stays, adding to the complexity (Ferreira and Carbonatto 2023).

While most studies emphasise the frequency of visits, less attention has been paid to the complex social, emotional, and practical factors that drive them (Seaton and Palmer 1997; Moscardo et al. 2000). Beyond logistical and financial aspects, transnational visits are deeply intertwined with emotional dimensions. These encounters, while enriching, expose the fragility of diasporic connections and highlight the duality of joy and strain inherent in transnational family life (Miah et al. 2022).

4. Results

4.1. Financial Constraints

4.1.1. High Cost of International Travel

Financial constraints serve as a substantial obstacle, often preventing parents from realizing their heartfelt desire to visit their emigrant children. For many, the financial burden of undertaking even a single visit is overwhelming, and the prospect of frequent trips becomes virtually unattainable. The exorbitant costs associated with international travel, particularly for parents from South Africa, create a formidable challenge. Chief among these costs is the expense of flight tickets, which often constitute the most significant financial hurdle.

I haven’t been able to visit “ D” overseas. The flights are just too expensive, and with my health, I don’t think I could manage the trip. It breaks my heart, but it’s just not possible. I don’t think I will ever see him again.

When considering the elevated costs of international travel alongside the unfavourable exchange rate of the South African rand against stronger currencies such as the New Zealand dollar, US dollar, British pound, or Australian dollar, these visits are often considered a luxury rather than a regular occurrence. The following participant describes the high cost of air tickets post-Covid, noting that they can only afford one trip per year.

Plane tickets once a year from the savings fund are all I can afford! The costs are unbelievable. Flight tickets to “T “after Covid are from R14,000 return, up to R26,000 return: “cattle class”. Double that for the two of us. All this for just a 2–3 weeks visit.

One participant shared the financial strain of such trips, highlighting the importance of careful planning to take advantage of discounted travel fares.

The cost of the trip was R45,000-00 for the two of us. We already bought the tickets with the Travel Expo in February, even though the trip was in November 2017. The discounted price of R9,000-00 per person with Qantas was only available in the “out of season” period.

For some parents, even if they have the financial means to travel, the high costs make it difficult to justify frequent visits. Striking a balance between visiting their emigrant children versus maintaining financial stability becomes a challenging dilemma. The following participant argued the absurdity of flight ticket prices, emphasising the complex financial calculus involved in these decisions. His response captures the emotional and practical conflict parents often face, as they weigh the significance of the visit against the staggering costs of international travel:

… It is terribly expensive. If I now had to, I would scratch the money out from somewhere and I can afford it, but I need to look after myself as well. Even if you have money, you don’t spend your money on something that is really absurd, like the price of air tickets at this stage is completely absurd

Participants acknowledged their privilege in being able to afford trips to visit their children, often recognising that such opportunities are not accessible to everyone. This participant simultaneously highlights the economic struggles faced by their children, who cannot afford to travel to South Africa. This financial asymmetry shifts the burden onto the parents, who not only cover their travel expenses but also provide monetary support to their children during these visits.

I come across people who struggle financially, and I think it must be very, very, very difficult. I really think we are incredibly privileged to be able to afford it financially. The children cannot afford to come here, um… that’s why we go there. And every time we go there, we give them a few dollars, which they can use to buy something for themselves on the other side. Life is quite expensive there. But to have the finances is definitely an advantage, definitely.

4.1.2. Hidden Costs of Parental Visitations

The financial strain of visiting emigrant children extends beyond airfare, with hidden costs adding to the burden. These trips require extensive planning, including securing flights, visas, passports, and travel insurance, alongside managing medical expenses. Medical expenses, often tied to mandatory examinations required for obtaining travel insurance, further increase the overall cost and complexity of travel.

We paid R62,000 for a flight last November for me and my husband. It’s without visas, passports, almost R9000 medical, which was mandatory by specific doctors. And then without pocket money and other normal expenses for going on holiday.

In addition to meeting all the health requirements, health insurance is usually required for the full period of the intended visit, to cover any medical costs which might arise.

South Africans need to apply for a visa to travel to Australia and the United States well in advance of the travel date. For many parents, obtaining a visa isn’t guaranteed, which heightens the emotional strain and limits their ability to plan visits confidently.

Definitely the costs and visas too. One always worries if the visa will be denied because of your age.

Some expenses are overlooked, such as buying gifts for family members, both abroad and at home. This can be a cultural expectation in many families, where the parent feels obliged to bring something for their emigrant children or to return with gifts for relatives back home.

Many small expenditures add up and can significantly inflate the overall cost of the visit.

About R35,000 for the two of us to the USA. Now visiting my son has become incredibly expensive. And then there’s the cost of what you contribute there, gifts you buy, take with you, and bring back for people at home. We prefer not to add it all up; ignorance is bliss.

Work limitations restrict many parents, especially those who may not have flexible schedules or sufficient leave, underscoring that finances alone don’t dictate visit frequency—practical responsibilities do as well.

I still have to pay the visas and the house sitter. I am still working, so unfortunately my work circumstances do not allow me to visit more often.

This participant’s children are covering the costs of their flights.

For sure the finances are the big issue, though I am very privileged that my children are still paying my plane tickets at this point.

4.2. Logistical Challenges

It was found that preparing for a visit presents significant logistical challenges, particularly for elderly parents. The physical and emotional demands of long-distance journeys can make such trips daunting, given the considerable distances South African parents often need to traverse.

Additional practical considerations, such as deciding on suitable accommodation for the parents and determining the duration of their stay, further intensify the complexities of planning. These factors not only add logistical challenges but also substantially increase the overall expenses, making transnational visits both financially burdensome and organizationally demanding.

4.2.1. The Impact of Home Accommodation on Visits

The choice of accommodation significantly shapes the overall experience of visits. Many parents opt to stay in their children’s homes, as this maximises their time together and allows full immersion in their children’s daily lives. One participant shared:

Staying with my child has the advantage that we see each other a lot more and you learn more about their way of life in New Zealand.

Proximity often creates opportunities for cherished moments and precious rituals such as morning cuddles with grandchildren before school, helping to renew and deepen relationships. As one parent explained:

Staying at their home was good because we could renew the bond with everyone, especially the grandchildren. They were still small enough to come and get into our bed with us in the morning for a while before school.

Living under the same roof provides parents with the opportunity to immerse themselves in daily routines and gain a rare, intimate glimpse into their children’s lives abroad. For many, the significance of these shared moments far outweighs the logistical challenges involved. As one respondent expressed:

What made the experience truly valuable was being able to live with “J “ and “M”. That was part of the reason for our visit—we wanted to spend just over three weeks with them, experiencing daily life, visiting shops, riding the bus and train, and immersing ourselves in their new country

However, staying in their children’s homes can present challenges, particularly when space is limited or routines are disrupted. One parent noted:

Staying at home is harder for the children and although they don’t say it, we feel after the second week it gets too long for everyone

For others, financial constraints leave no option but to stay with their children, despite potential challenges. Practical factors, such as the size and comfort of the home, can shape the experience, as one respondent shared:

It was a bit awkward because “H’s” mother was also staying with them at the time. She had to give up her room with the double bed and move to sleep in the living room. They had a two-bedroom home, so “G” and “E” (their grandchildren) had to share one room, and we stayed in the other room. We were there for three weeks, and although it might have felt disruptive to them, I think they genuinely appreciated that we made the effort to visit. Overall, I think things went well.

For some parents, the desire to be close to their children outweighs comfort concerns, as one parent expressed:

I think it depends on whether or not the children’s home has sufficient space. I will stay anywhere, as long as it is close to the kids, so that we can be together every day.

Despite the joy of shared time, staying in their children’s homes often brings a subtle awareness of intruding on their privacy and routines. As one parent explained:

Reasonably, I felt that I was intruding on their privacy. I try to stay in my room until they left for work.

For many parents, the opportunity to be present in their children’s lives abroad outweighs the inconveniences of accommodation. The emphasis shifts from logistical concerns to the joy of shared time:

It was a fantastic experience, regardless of where we stayed.

4.2.2. The Impact of the Length of Stay on Parental Visits

The length of stay plays a significant role in shaping the experience of transnational visits, influencing both practical and emotional dynamics. Longer visits often mean increased expenses for food, travel, and other daily needs, adding to the financial burden. These costs often determine whether parents can afford the trip independently or require financial support from their children.

Many parents feel that short visits of one to two weeks are not justifiable due to the high cost of international travel. As one parent explained:

It is so expensive and far, one has to stretch the time—as long as the visa allows.

The duration of visits in this study ranged from three weeks to six months, with most parents trying to strike a balance between maximising their time abroad and avoiding overstaying their welcome. One respondent shared:

We chose 3.3 weeks to visit (with 3 weekends included) because I am the breadwinner and could not take longer leave. It also doesn’t feel right to stay at our children’s home that long. Accommodation in NZ is very expensive. To justify the expense, I wouldn’t want to visit for less than 3 weeks. It is a luxury and not a necessity (my wife might feel differently about this …).

There is a delicate balance between financial constraints, their role back home, and maximising the value of their time abroad. For many, the duration of the visit is also influenced by how long they feel comfortable staying in their children’s homes without overstaying their welcome. A participant shared:

We need to find a balancing act on such visits—finding ways to be involved and present without intruding on the daily flow of life. The 7 weeks felt too long for us and our children but the second visit of 4 weeks was fine for both parties.

The emotional impact of the visit duration also varies. Short visits are often easier to manage but may lack the depth of connection afforded by longer stays. A participant noted the following:

Oh I think it depends on people. If we go for a short time, we prepare for that. The first time was short, and it was fine. Now we stayed longer and it was difficult to leave again—we got too attached. The longer, the more fun. But we need to come home again. Life must go on!

Some parents opted for extended visits, yet these extended stays can sometimes lead to feelings of homesickness as one parent explained:

I have found that 3 months can get a bit long. You miss your family and start longing to go back home.

However, this sentiment isn’t universal. There’s no one-size-fits-all approach to these visits. While some parents appreciate the opportunity to build strong emotional bonds during longer visits, others are mindful of their children’s routines and the need to balance time spent abroad with responsibilities back home. As another parent reflected:

Although it is wonderful to visit, the children there also have their own lives and routines. We also longed for our other children back home.

4.2.3. The Impact of Distance and Physical Strain on Parents

The geographical distance between South Africa and the popular emigration destinations such as Australia, the United States, and New Zealand presents significant obstacles to parental visits. The sheer physical distance makes travel arduous, especially for elderly parents, who often face additional challenges associated with long-haul flights, extended layovers, and demanding itineraries.

Time zone changes and hours in transit leave many parents physically and mentally drained. As one participant shared:

The trip to America… there’s a lot of jetlag, and it’s not an easy trip to make. You know, if your kids are in Europe or England, there’s no time delay, no jetlag or anything like that.

Distance can pose a significant obstacle to maintaining long-term connections, as the journey itself is often strenuous and challenging, particularly for older parents. A detailed account of one journey illustrates the complexity:

We usually fly from Cape Town at around one o’clock in the afternoon. It’s a two-hour flight to Johannesburg, but you need to arrive at the airport well in advance for check-in. From Johannesburg, the flight to Sydney takes twelve and a half hours, followed by a two-hour layover, assuming the flight is on time. Then there’s another hour-and-a-half flight to Hobart, making it an exhausting journey.

Jetlag is a significant challenge for parents travelling long distances to visit their emigrant children, as highlighted in the following quotation:

Aaii, there, this is somebody that you love and his family and they are far away. Too far away! Last year when I went across for the first time, they had a direct flight from here, to just beyond Miami but it was still 15 h in the plane. And going there was fine, but coming back I had the most horrific jetlag, much more than travelling to Europe or England.

4.3. The Impact of Age-Related Vulnerabilities on Visits

As parents age, the awareness of their mortality and the finite opportunities for future visits bring an added layer of emotional intensity to transnational visits. The recognition that these moments together may be among the last creates a profound sense of both urgency and loss. A participant shared the following realisation:

… If I can see my child once a year, that would make it different. If I had the money to fly down every year to see him in New Zealand it would not be that bad. I can live with that. Even with your children staying in South Africa, seeing them once a year over Christmas is the norm, it is not a strange thing, so I could live with that. But the fact knowing, that I will see him … Say now I live ‘till eighty, I will see him hopefully … three or four times before I die. That is … what is … killing me…

Despite the best intentions, many elderly parents must confront the painful reality that they can no longer make every trip possible, as one respondent shared about her daughter’s shifting perspective:

I often told her, Sus, the time will come when we can no longer go and then she said no we will make a plan. And now she realises that she cannot make a plan with everything and now she has to adjust herself to that as well. And it is not easy for her, she said to me the other day ma I promise you, you will see me once a year, but it is such a schizophrenic situation. She realises that we will perhaps, we will definitely not go again … but the visits were very important to me, but that’s now over.

With advancing age, long-distance travel becomes more physically demanding, and health conditions may limit the ability to travel altogether. Addressing the increasing health and age concerns that make travel difficult as parents age as seen in the following response:

We went for the last time now. it is quite simply, no more, it is a risk, my husband is 85, you no longer get insurance and the insurance that you do get, excludes any heart condition or cerebral, let’s say a stroke or a heart attack are excluded, so even if you pay a lot, you cannot claim insurance for conditions which are in actual fact conditions that afflict the elderly.

The lack of reliable insurance coverage means that even elderly parents who can afford to travel may face significant vulnerabilities, amplifying the anxiety surrounding transnational visits. The potential health risks associated with prolonged travel, such as the physical toll of sitting for extended periods, add to these concerns. Additionally, the emotional strain is heightened by fears of experiencing a medical emergency while abroad, far from familiar healthcare systems and support networks.

4.4. Impact of Strained Pre-Emigration Relationships on Family Visit Dynamics

Strained pre-emigration relationships can pose significant barriers to visiting, as unresolved tension or conflict may amplify feelings of resentment. Instead of looking forward to meaningful family time, parents with unresolved issues may approach visits with a sense of dread or not visiting at all.

My husband is the problem here, he experiences it extremely negatively that they are no longer available. So much so that he will almost only talk to her under duress and not at all to our son-in-law, also says he won’t visit again because that greeting is just too horrible.

Conflict with in-laws can add another layer of complexity, introducing additional barriers to visits.

We and our daughter-in-law already had problems before they left here, so it had a very negative influence in some ways

Relational strain, both with the child and their spouse, can shape the decision to visit as well as the quality of interactions during these short reunions.

4.5. The Emotional Weight of Saying Goodbye

For many parents, the farewell at the end of a visit is one of the most challenging parts of their transnational visit experience. The contrasting emotions of the initial joy of reuniting and the inevitable sorrow of parting create a profound emotional intensity. As one parent describes it:

The hardest part was keeping myself “together” when we approached the reception area of the airport in the far country where she was waiting for us. Those accumulated emotions of what it will be like to see her again after such a long time, and to hold her in my arms again, to hear her saying “hello mom” and not just see her on a mobile phone screen. Then of course the greeting, from “tata mamma”, and again those arms with her warm hug to feel her, and I also realise that the difficulty goes both ways.

For many separated families, the rarity of physical closeness transforms it into a deeply cherished and irreplaceable experience.

Not knowing when the next opportunity to visit will arise adds a profound layer of emotional complexity. For many families, this unpredictability leaves them without a concrete timeline to look forward to, intensifying feelings of uncertainty and longing. As one parent reflects:

Most definite saying goodbye, not knowing when there will be an opportunity to visit and the cost of travelling is sadly unbelievable!

The following response captures the fleeting nature of time, particularly during airport goodbyes. For many families, the airport represents a duality—a gateway to reunions and a place of farewells:

Gosh, the vacation was over, and little did I know what a great disillusionment awaited us at the airport… Sydney Airport was so overwhelming for us; there wasn’t even time for a proper goodbye or a selfie! I boarded the plane with tear-filled eyes, barely caring about the others staring at me, or so it felt.

The challenge doesn’t end with the farewell; for many, the sadness lingers, extending into the weeks after their return home.

And then a big factor is the sadness with the goodbye and for weeks after that you still struggle and can’t get back on track properly. For me, it gets more intense every time.

The feeling of missing out often brings a profound awareness of lost time irretrievable as both parents and children age and change. As one participant noted:

…because both parties are getting older, changing and evolving it might feel like time has been “wasted”

Saying goodbye after a transnational visit is especially emotional for grandparents, as their bond with grandchildren holds deep intergenerational significance. These farewells, regardless of the grandchildren’s age, are marked by intense emotional strain.

I will never forget, not this time, the previous time that we visited, we left from “C” and we then had already requested a wheelchair for my husband for the long distances that you need to walk to the gates. And then, “J” was already at university, he is the oldest, he asked where we were checking in, there he asked the counter official:

May I push my Grandpa to the gate, may I go through the security zones with him? And uhm … it was incredible for my husband uhm … precious when he bade him farewell [very sad, long silence] … he embraced him and said Oupa you will never know what you meant to me and how much I have learnt from you. So that satisfaction we do have…

Saying goodbye to younger grandchildren after a transnational visit is especially emotional.

The image that sticks in my mind is of my two grandsons walking away from me with their backpacks. We spent two hours with them at the airport, but that image is all I can remember.

5. Discussion

The findings of this study illuminate the multifaceted challenges faced by South African parents in maintaining connections with their emigrant children. Transnational families rely on two primary means of connection: virtual communication and in-person visits. These play vital roles in bridging the physical divide (Schuler et al. 2022). Virtual communication creates consistent interaction and emotional closeness, but it lacks the depth and authenticity provided by shared physical spaces. Visits, therefore, become unique opportunities for parents to immerse themselves in their children’s daily lives, engage in meaningful face-to-face interactions, and reinforce familial bonds across generations (Schuler et al. 2022; Baldassar 2007a; Marchetti-Mercer 2012).

A prominent theme in this study is the deep longing of transnational parents to share the same space as their children and grandchildren. Visiting them fulfils a desire to “be there”, experiencing touch, hugs, and spontaneous moments. For many, “seeing with their own eyes” the environments where their emigrant children now live satisfy a profound need for tangible connection (Marchetti-Mercer et al. 2021). However, financial, health and logistical barriers often make it difficult for South African parents to visit more frequently—or at all.

The findings reveal the complex and multifaceted barriers that South African parents face in maintaining transnational family connections with their emigrant children. These hurdles often intersect, not only shaping the feasibility and frequency of visits but also influencing their emotional and practical outcomes. Financial constraints are a central barrier for South African parents attempting to visit their immigrant children. High costs, including airfare, visas, travel insurance, and unfavourable exchange rates against currencies like the US dollar and the British pound, often make such visits unattainable for many. As a result, transnational visits are frequently viewed as a luxury rather than a routine family practice.

The frequency of visits among participants varied significantly, reflecting a spectrum of circumstances and constraints. While some parents were able to visit their emigrant children multiple times, others struggled to afford even a single trip. This observation echoes the findings of Miah (2023) and Miah and King (2021), who highlight the reality that visits, while essential for maintaining familial bonds, remain an unevenly distributed privilege shaped by financial capacity.

The experience of not seeing one another for long periods, such as five to seven years, can create a noticeable gap in the connection between parents and children. Even though the emotional bond may still be strong, the time apart leads to significant differences in the way each person experiences their daily life and environment. These differences—whether in routine, cultural influences, or lifestyle—can make it difficult to reconnect and adjust when finally reunited. The time and experiences that have shaped each person during the separation may create a sense of unfamiliarity, making it harder to bridge the gap and return to the closeness that once existed (Ferreira 2023).

The differing cultures and worldviews within transnational families often hinder mutual understanding, complicating the process of reconnection. Although family members may wish to be involved in each other’s lives, the reality is that they exist in distinct social and cultural contexts. These divergent experiences create a barrier to full comprehension, despite the emotional bond, making cross-cultural understanding more challenging.

Airfare alone represents a significant financial hurdle, with participants consistently emphasising the steep price of flight tickets. To opt for more affordable options often results in multiple stopovers, making the journey more arduous, particularly for elderly travellers. This factor is particularly impactful given the long distances involved in travelling from South Africa to popular emigration destinations. The findings of this study align with Marchetti-Mercer et al. (2021) research, highlighting the significant challenges associated with planning visits due to financial constraints. The cost of international travel to geographically distant countries such as Canada, New Zealand, Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom emerged as a primary barrier to frequent visits.

The financial strain extends beyond travel logistics. Alongside airfare, many hidden costs greatly increase the financial burden of international travel. South African parents must obtain visas for most destinations, which can involve substantial application fees. Additionally, they face other expenses, such as mandatory health insurance and medical examinations, all of which need to be arranged and paid for in advance. These health-related requirements often come with higher premiums for the elderly. While often overlooked, these additional costs significantly add to the overall financial strain of planning a visit to a foreign country.

The financial challenges align with observations made by (Miah and King 2021) who note that international mobility travel is not “a level playing field”. It is far more accessible for individuals from affluent countries with visa-free travel privileges. By contrast, those from less economically advantaged nations, such as those in the Global South, encounter significant barriers shaped by restrictive visa policies and economic disadvantage. These systemic inequalities exacerbate the financial strain on parents, making it increasingly difficult to maintain transnational family connections (Miah and King 2021).

Cultural expectations, like buying gifts for emigrant children and grandchildren back home, add to the hidden costs of visits. Although seemingly minor, these expenditures and other incidental costs like pocket money accumulate over time, significantly impacting the overall financial feasibility of visits. Following the classic studies by Mauss (1990) and Gregory (2015), gifting is regarded as an obligated “social practice” and a “moral economy” based on generosity, reciprocity, and respect. It is simply inconceivable to arrive empty-handed.

Participants consistently reported the need to carefully evaluate the financial implications of visiting their emigrant children against their need for financial stability. These reflections emphasise the internal conflict parents face between emotional needs and practical financial considerations. Such decisions are often complicated by limited retirement savings and unfavourable exchange rates, creating added financial strain for transnational visits. Similarly, Marchetti-Mercer et al. (2021) identified the financial difficulties South African families encounter when trying to visit their emigrant children.

Many parents must confront the reality that limited resources will restrict the number of visits they can undertake in their lifetime. This awareness heightens the emotional intensity of each trip, and even parents who can afford occasional visits are acutely aware of the finite number of visits they may have left, which heightens feelings of urgency and loss.

The means for funding transnational visits varied among participants. While some parents covered the costs themselves, others relied on their emigrant children to fund their visits. Some elderly people did not feel comfortable using their pension money to undertake these trips and expected their children to cover the costs. Children covering travel expenses can be seen as a form of remittance. Typically, remittances refer to money or goods sent by migrants to their families in the home country, often to cover essential expenses like housing, education, or medical care (Bryceson 2019). This practice highlights the reciprocal nature of transnational family relationships, where parents and children share financial and emotional responsibilities. The act of receiving such support not only alleviates financial burdens but also fosters a sense of being valued and cared for, which is crucial for their emotional state (Venter and van Wyk 2018).

The vast geographic separation between South Africa and many popular immigration destinations emerged as another significant hindering factor in transnational visits. The considerable distance, combined with the effects of jet lag, makes travel exhausting, time-consuming, and logistically challenging for many parents. A parent remarked on the relative ease of travel for families whose children have immigrated to Europe, emphasising that the shorter travel time to European destinations makes those visits less burdensome by comparison to trips to Australia or Canada.

For many parents, visiting their emigrant children intensifies their awareness of the vast geographical distance. While these visits provide an opportunity to reconnect and witness their children’s lives first-hand, the tangible experience of travelling long distances reinforces the reality of the significant separation. The contrast between the closeness experienced during the visit and the reality of living apart often deepens the sense of loss, making the distance feel even more significant.

The high cost of international travel often compels South African parents to stay with their emigrant children during visits. While these extended stays justify the expense and strengthen family bonds by maximising time together, they also add complexity to the dynamics of cohabitation. The choice to stay in their emigrant children’s homes significantly influences parents’ experiences during transnational visits. Living under the same roof provides parents with an intimate view of their children’s daily lives and nurtures cherished rituals and meaningful connections, particularly with grandchildren, but can also bring challenges that require adaptation and understanding.

Household routines can feel unfamiliar as parents deal with the constraints of limited space and privacy while striving to balance the joy of togetherness with the realities of shared living. While living with family can enhance relationships, some parents might feel like guests in their children’s homes, resulting in unforeseen stress during visits. Parents faced additional challenges as they adjusted to a major role reversal, moving from hosts to visitors in their children’s homes. Prolonged stays in children’s homes can ultimately strain family dynamics. Similarly, among British Bangladeshi families, visitors often stay with relatives due to cultural expectations of hospitality and the high cost of commercial accommodation (Miah and King 2021).

The length of visits to emigrant children influences the financial and emotional aspects of transnational journeys. Longer visits validate the high travel costs and foster deeper connections but raise expenses and can disrupt household routines, leading to potential strain. Shorter visits, while less disruptive, are often seen as insufficient for meaningful reconnection and financially impractical due to high travel costs. Finding a balance between maximizing the value of time spent abroad and avoiding overstaying their welcome emerged as a central theme.

Long-distance travelling can be physically demanding. As parents age, they struggle with navigating busy airports, managing luggage, and handling layovers, which can increase stress, especially when travelling alone. The advancing age and declining health of elderly individuals affect their ability to travel long distances. This finding aligns with Marchetti-Mercer et al. (2021), who emphasised the same impact on elderly parents’ travel capabilities.

The emotional burden of saying goodbye often overshadows transnational visits from the moment of arrival. For many participants, the joy of being together is diminished by the looming anticipation of parting. Many grandparents recount the emotional distress of parting, often accompanied by the uncertainty of when—or even if—they will see their children and grandchildren again. This separation illustrates the concept of ambiguous loss where grandparents experience a profound sense of grief and loss, despite their loved ones being alive and emotionally connected to them. This paradoxical reality—where loved ones are present emotionally but inaccessible physically—creates a state of unresolved grief (Boss 1993).

Saying goodbye after a meaningful visit can be very challenging. A recent article on the “three-minute hug” illustrates how brief yet emotionally intense these moments can be, making farewells even harder for parents (Ferreira 2024). For some, the prospect of these goodbyes is so overwhelming that it deters future visits, as the emotional toll can overshadow the joy of their time together. Ambiguous loss is particularly relevant in the context of emigration, which is described as a systemic and ongoing interactional phenomenon. As Boss (1993, p. 368) explains, “The family consists not only of the system left behind but also includes, at least in their minds, the émigré who has gone to a new land”. As Boss (2004, p. 551) notes, “When a child emigrates, the family left behind begins a journey toward healing that continues, realistically speaking, through the rest of their lives”. For grandparents, the separation initiates an ongoing process of emotional adjustment and healing, which often continues throughout their lives.

Each visit represents a cyclical form of loss, in which parents must repeatedly face separation from their children after experiencing the closeness of in-person interactions. Unlike traditional forms of loss, ambiguous loss offers no sense of finality or closure, intensifying the emotional weight. Grandparents often describe a lingering sense of yearning and an inability to fully process the separation, as the relationship remains intact yet physically disrupted.

Some visits carry a sense of finality; for older parents, it may be the last chance to see loved ones, offering an opportunity for a final face-to-face farewell. The emotional challenge of parting ways while uncertain about future visits embodies what Moss et al. (1985, p. 137) call the “inherent dialectic of separation and hope”, illustrating the delicate balance between the joy of connection and the sorrow of separation, alongside concern for future encounters. This fear amplifies the emotional intensity of each farewell.

Parents experienced uncertainty about future visits, intensifying the emotional strain of goodbyes. The realisation of a final visit can evoke profound emotions. For those aware it may be their last, each moment carries an intense urgency resulting in deep appreciation mingled with sorrow, as interactions can feel like farewells. Conversely, those unaware of the finality may experience unexpected grief and regret upon later realisation. This loss can also be understood through the concept of ongoing sorrow—a persistent emotional pain that resurfaces during farewells, holidays, and milestones, emphasising the absence of emigrant children (Teel 1991). Unlike pathological grief, ongoing sorrow intertwines with moments of joy and satisfaction but reflects the enduring gap between parents’ reality and their unfulfilled dreams of closeness and connection with their children and grandchildren (Roos 2001, 2002). Emigration’s emotional toll is not a singular event but a continuous and recurring process of living loss (Eakes 1995).

Strained pre-emigration relationships can significantly impact the dynamics of family visits, often creating tension and discomfort. Unresolved conflicts or lingering misunderstandings may prevent both parents and emigrant children from fully relaxing and enjoying their time together. This emotional strain can lead to increased stress, reduced visit frequency, or, in some cases, the complete absence of visits, as the perceived emotional burden outweighs the motivation to reconnect. Unresolved issues can impede open communication, making it challenging to address logistical or interpersonal challenges that may arise during visits, thereby exacerbating the strain on familial bonds.

The mix of emotions evident in visits reflects the ambivalence that has been reported as characteristic of the emotional economy of transnational family lives (Baldassar 2007a, 2007b).

6. Material and Methods

This article is part of an ongoing research project aimed at understanding the experiences of South African parents whose adult children have emigrated. It examines a theme from the researcher’s doctoral thesis, “Parents Left Behind After the Emigration of Their Adult Children: An Experiential Journey” (Ferreira 2015), which focused on transnational family dynamics following emigration. The study addressed the research question: “What are the experiences of South African parents left behind once their adult children have emigrated?”

A qualitative research approach was chosen it allows for the exploration of knowledge beyond statistical data by prioritising the lived experiences of participants and the meanings they ascribe to these experiences. This approach aligns with the objectives of the study, which seek to understand, rather than explain, the phenomena associated with the emigration of adult children and its impact on South African parents left behind (Ferreira 2015). Qualitative methodologies, as described by Hamilton and Finley (2019) enable a comprehensive examination of data, emphasising its depth, multiplicity, and richness. Similarly, Schurink et al. (2011) highlight that qualitative research is particularly suitable for interpreting the meaning participants attribute to their lived experiences, making it an appropriate framework for this study.

From the author’s original study, four key themes were identified: Emigration of the adult child—focusing on the decision-making process and its impact on families. Emigration loss—addressing the emotional and relational challenges of separation. Intergenerational relationships—exploring how relationships adapt and change across distances. Transnational communication—examining the ways families maintain connections, with visits emerging as a significant subtheme.

Participants frequently reflected on their visiting experiences - or the absence of visiting or infrequency of such visits—to their emigrant children. These reflections highlighted the central role of visits in sustaining familial bonds while also revealing the emotional, logistical, and financial challenges that complicate these encounters. Their reflections revealed the importance of examining not only the dynamics and significance of transnational visits but also the multifaceted factors that hinder or complicate these encounters. Therefor this article this article focuses on transnational visits, exploring their dynamics, significance, and barriers.

- Participants

For the original study, participants were selected using non-probability purposive sampling for the first participant, followed by snowball sampling to identify additional participants (Strydom and Delport 2011). The inclusion criteria required participants to be: South African citizens of any race, culture, religion, or gender, residing in Gauteng province aged between 50 and 85 years; fluent in English; and parents of adult child(ren) who had emigrated and lived abroad for at least one year. For the ongoing research, an additional 13 participants were recruited with the added criterion of having visited their emigrant children.

Table 1 provides the demographic and migration details of the 37 participants of this study. While most participants have visited their children abroad, five participants from the original study could not undertake such visits, citing financial constraints and health-related vulnerabilities as the primary barriers. Their inclusion in the study is particularly significant, as their experiences highlight the hindering factors that prevent visits.

Table 1.

Parent’s Demographic and Emigration Details.

The participants range in age from 52 to 79 years, reflecting the older demographic typically associated with parents and grandparents of emigrant children. Most participants in this study were female. The most common emigration destinations for their children include Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, and the United States, which aligns with global trends of South African emigration to English-speaking, economically developed countries. The less common destinations, such as Germany, Sweden, and China, indicate diverse migration patterns. The destinations mentioned (e.g., Australia, New Zealand, and the United States) require long-haul flights and significant travel time. The cost of flights, accommodation, and potential travel insurance for older travellers is extensive. Six participants have more than one emigrant child, and among these, three participants have children residing in different countries.

- Instruments

In both the original study and ongoing study, data collection involved a bio-sociodemographic questionnaire that gathered information such as age, gender, education, marital status, and house. In the original study unstructured, face-to-face interviews were conducted with participants. These unstructured interviews, as described by Islam and Aldaihani (2022), facilitated an open, conversational approach, allowing participants to share their experiences spontaneously and authentically.

To adapt to the evolving focus on transnational visits, additional data collection methods were introduced. Participants could either provide written responses to qualitative surveys (Braun et al. 2020) or engage in audio-recorded, semi-structured internet interviews. The qualitative survey method was chosen for its ability to capture the nuanced, subjective experiences and emotional complexities of parents during these visits. Qualitative surveys align with qualitative research values, as they authentically reflect participants’ narratives, offering a deeper understanding of the personal meanings they attribute to these visits (Braun et al. 2020). Similarly, as outlined by Woodrow (2006), semi-structured interviews balance guided discussion with the freedom for participants to express their experiences in their own words, providing valuable depth and nuance. Together these methods enhance the study’s ability to uncover the complexities of transnational visits.

- Data Collection and Analysis

The audio recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim, ensuring that all spoken content was captured accurately. To achieve a comprehensive understanding of the data, each interview was listened to multiple times to gain a holistic overview of participants’ narratives, following the guidelines proposed by Schurink et al. (2011).

In the original study, qualitative data analysis was conducted using the ATLAS.ti software, which proved highly effective in managing and analysing large volumes of qualitative data. The software facilitated the retrieval of coded data, identification of patterns, and the organization of nuanced details.

For the ongoing research project, data analysis adhered to Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step framework for thematic analysis. This approach was selected for its methodological rigour and flexibility, allowing for a rich and detailed exploration of the data.

Phase 1 involved familiarisation with the transcribed data through repeated readings and note-taking of key ideas. It included revisiting the original study’s objectives and findings alongside new participant responses, to establish continuity between the original research and the ongoing research. In Phase 2, original codes were revisited and supplemented with new codes from the additional dataset. Phase 3 involved organising codes from both datasets into potential themes, prioritizing transnational family dynamics while allowing new themes to emerge, and highlighting continuities and differences in participants’ experiences.

In Phase 4, themes were systematically reviewed for coherence and rigour, integrating findings from the original study with new data to develop a thematic map reflecting continuity and expansion. During phase 5, defining and naming themes, previously identified themes were revisited and refined to enhance their relevance to the aims of the ongoing research. New themes were named and defined as necessary to accurately represent the expanded dataset. In Phase 6 a comprehensive report was produced, using representative data examples to illustrate themes and linking findings to research questions and literature.

Insights from both datasets provided a richer perspective on transnational family dynamics and participants’ evolving experiences. To ensure credibility, this study incorporates verbatim excerpts from participants’ narratives, following Polit and Beck (2016). These excerpts enhance authenticity, uphold confidentiality, and provide a deeper understanding of the findings.

- Ethical Considerations

For the ongoing research, renewed ethical approval was obtained from the University of Pretoria Ethical Committee. Participation was entirely voluntary, with the option to withdraw at any stage. Each participant signed a voluntary consent form, which detailed the study, obtained permission to participate, consented to audio recording of interviews, allowed the use of direct quotations, and assured the protection of their identities. Confidentiality was ensured by assigning pseudonyms to all participants. Confidentiality was integral to the research process.

- Limitations of the Study

This study explores the under-examined experiences of South African parents visiting emigrant children and grandchildren. Given the limited literature specific to this context, insights were drawn from related research in other cultural and geographical settings, which may not fully capture the unique South African experience. While the small sample size aligns with the qualitative focus on depth, it inherently limits the generalisability of the results, emphasising the value of rich, detailed narratives over broad representativeness.

7. Conclusions

For South African parents, transnational visits and digital communication represent essential strategies for preserving familial identity and emotional bonds. However, these efforts require continual negotiation and adaptation in response to shifting life circumstances, including ageing, health challenges, and changing family dynamics.

Migration is not a singular event but an ongoing journey that transforms familial connections and requires resilience from all members of transnational families. This study addresses a key gap in the literature by exploring the significance of transnational visits, offering insights into how South African families navigate geographic separation.

The findings reveal a complex interplay of financial, logistical, emotional, and relational factors that limit parents’ ability to visit their emigrant children as frequently as they desire—or at all. While financial constraints are the primary barrier, strained pre-emigration relationships can also deter visits. The research emphasises the need to balance practical limitations with emotional and relational needs, advocating for a holistic understanding of transnational family dynamics.

Ultimately, migration disrupts the emotional, cultural, and social bonds within transnational families, requiring continuous adaptation and resilience. The metaphor “Mind the Gap” captures parents’ ongoing struggle to bridge both physical and emotional distances, reflecting their unwavering commitment to maintaining meaningful connections with their children across borders.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

University of Pretoria in 2015 and again in 2024 HUM026/0824.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

The data op of the initial study is kept at the University of Pretoria.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Aviram-Freedman, E. 2005. “Making oranges from Lemons”. Experiences of Support of South African Jewish Senior Citizens Following the Emigration of Their Children. Ph.D. dissertation, University of the Western Cape, Cape Town, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Baldassar, L. 2007a. Transnational Families and Aged Care: The Mobility of Care and the Migrancy of Ageing. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 33: 275–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassar, L. 2007b. Transnational Families and the Provision of Moral and Emotional Support: The Relationship between Truth and Distance. Identities: Global Studies in Culture and Power 14: 385–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassar, L. 2008. Missing kin and longing to be together: Emotions and the construction of co-presence in transnational relationships. Journal of Intercultural Studies 29: 247–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baldassar, L., and R. Wilding. 2020. Migration, Aging, and Digital Kinning: The Role of Distant Care Support Networks in Experiences of Aging Well. The Gerontologist 60: 313–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boss, P. 1991. Ambiguous Loss. In Living Beyond Loss: Death in the Family. Edited by F. Walsh and M. McGoldrick. New York: Norton, pp. 237–46. [Google Scholar]

- Boss, P. 1993. The experience of immigration for the mother left behind: Feminist strategies to analyze letters from my Swiss grandmother to my father. Marriage and Family Review 19: 365–78. [Google Scholar]

- Boss, P. 1999. Ambiguous Loss: Learning to Live with Unresolved Grief. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Boss, P. 2004. Ambiguous Loss Research, Theory, and Practice: Reflections after 9/11. Journal of Marriage and Family 66: 551–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 3: 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., V. Clarke, E. Boulton, L. Davey, and C. McEvoy. 2020. The online survey as a qualitative research tool. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 24: 641–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryceson, D. F. 2019. Transnational Families Negotiating Migration and Care Life Cycles across Nation-State Borders. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 45: 3042–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryceson, D. F., and U. Vuorela. 2002. Transnational families in the twenty-first century. In The transnational family: New European Frontiers and Global Networks. Edited by D. F. Bryceson and U. Vuorela. New York: Oxford International, pp. 3–30. [Google Scholar]

- Buckham, D. 2019. Are Skilled, White South Africans Really Emigrating at an Accelerating Rate? Available online: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2019-10-01-are-skilled-white-south-africans-really-emigrating-at-an-accelerating-rate/ (accessed on 20 January 2025).

- Carling, J. 2002. Migration in the age of involuntary immobility: Theoretical reflections and Cape Verdean experiences. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies 28: 5–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climo, J. J. 1988. Visits of distant living adult children and elderly parents. Journal of Aging Studies 2: 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Climo, J. 1992. Distant Parents. New Brunswick: Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Crush, J. 2000. Losing Our Minds: Skills Migration and the South African Brain Drain. Waterloo, ON: Southern African Migration Programme, rep., i-63; SAMP Migration Policy Series No 18. [Google Scholar]

- Eakes, G. G. 1995. Chronic sorrow: The lived experience of parents of chronically mentally ill Individuals. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing 9: 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falicov, C. J. 2005. Emotional transnationalism and family identities. Family Process 44: 399–406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falicov, C. J. 2007. Working with transnational immigrants: Expanding meanings of family, community, and culture. Family Process 46: 157–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S. 2015. Parents Left Behind in South Africa After the Emigration of Their Adult Children: An Experiential Journey. Ph.D. thesis, University of Pretoria, Pretoria, South Africa. Available online: https://repository.up.ac.za/bitstream/handle/2263/50900/Ferreira_Parents_2015.pdf (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Ferreira, S. 2023. The Impact of Emigration on Familial Bonds. Daily Maverick. Available online: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2023-06-20-emigration-and-its-impact-on-familial-bonds/ (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Ferreira, S. 2024. When Three Minutes Is Enough—The Kindness of a Quick Goodbye. Daily Maverick. Available online: https://www.dailymaverick.co.za/article/2024-11-11-when-three-minutes-is-enough-the-kindness-of-a-quick-goodbye/ (accessed on 27 January 2025).

- Ferreira, S., and C. L. Carbonatto. 2023. My granny lives in a computer: Experiences of Transnational Grandparenthood. Journal of Loss and Trauma 28: 635–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fourie, J. 2018. The Cost of Crime. News24. Available online: https://www.news24.com/Finweek/Opinion/the-cost-of-crime-20180815 (accessed on 12 November 2024).

- Fraser, L. 2024. The Countries Where Most South Africans Emigrate to. BusinessTech. Available online: https://businesstech.co.za/news/lifestyle/745261/the-countries-where-most-south-africans-emigrate-to/ (accessed on 21 January 2025).

- Glick Schiller, N., L. Basch, and C. Blanc-Szanton. 1992. Towards a definition of transnationalism. In Towards a Transnational Perspective on Migration: Race, Class, Ethnicity and Nationalism Reconsidered. Edited by L. Basch, N. Glick Schiller and C. Blanc-Szanton. New York: New York Academy of Sciences, pp. ix–xiv. [Google Scholar]

- Goldin, J. 2002. Belonging to two worlds: The experience of migration. South African Psychiatry Review 5: 4–8. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, C. A. 2015. Gifts and Commodities. Chicago: HAU Books. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilton, A. B., and E. P. Finley. 2019. Qualitative methods in implementation research: An introduction. Psychiatry Res. 280: 112516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Höppli, T. 2014. Is the Brain Drain Really Reversing? New Evidence. Policy Research on International Services and Manufacturing Working Paper 1. Cape Town: PRISM, University of Cape Town. Available online: http://hdl.voced.edu.au/10707/351589 (accessed on 6 February 2024).

- Isaksen, L. W., S. U. Devi, and A. R. Hochschild. 2008. Global Care Crisis: A Problem of Capital, Care Chain, or Commons? American Behavioral Scientist 52: 405–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, A., and F. M. F. Aldaihani. 2022. Justification for Adopting Qualitative Research Method, Research Approaches, Sampling Strategy, Sample Size, Interview Method, Saturation, and Data Analysis. Journal of International Business and Management 5: 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janta, H., S. A. Cohen, and A. M. Williams. 2015. Rethinking visiting friends and relatives mobilities. Population, Space and Place 21: 585–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaplan, D., and T. Höppli. 2017. The South African brain drain: An empirical assessment. Development Southern Africa, Taylor & Francis Journals 34: 497–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, R., and J. Vullnetari. 2006. Orphan pensioners and migrating grandparents: The impact of mass migration on older people in rural Albania. Ageing Society 26: 783–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knodel, J., and C. Saengtienchai. 2007. Rural parents with urban children: Social and economic implications of migration for the rural elderly in Thailand. Population, Space and Place 13: 193–210. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/56030 (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Lemaitre, G. 2005. The Comparability of International Migration Statistics—Problems and Prospects. OECD Statistics Brief July 2005, No. 9. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/migration/49215740.pdf (accessed on 25 January 2025).

- Levitt, P., and N. G. Schiller. 2004. Conceptualizing simultaneity: A transnational social field perspective on society. International Migration Review 38: 1002–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lubbe, C. 2007. Mothers, Fathers, or Parents: Same-Gendered Families in South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology 37: 260–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabandla, N., M. C. Marchetti-Mercer, and L. Human. 2022. Meaning and Experience of International Migration in Black African South African Families. Contempory Family Therapy 45: 475–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti-Mercer, M. C. 2009. South Africans in flux: Exploring the mental health impact of migration on family life: Review article. Journal of Depression and Anxiety 12: 129–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Marchetti-Mercer, M. C. 2012. Those Easily Forgotten: The Impact of Emigration on those left Behind. Family Process 51: 376–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marchetti-Mercer, M. C., L. Swartz, and L. Baldassar. 2021. Is Granny Going Back into the Computer?: Visits and the Familial Politics of Seeing and Being Seen in South African Transnational Families. Journal of Intercultural Studies 42: 423–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mauss, M. 1990. The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Miah, M. F. 2023. Disrupted Mobilities: British-Bangladeshis Visiting Their Friends and Relatives During the Global Pandemic. In Anxieties of Migration and Integration in Turbulent Times. Edited by M. L. Jakobson, R. King, L. Moroşanu and R. Vetik. IMISCOE Research Series. Cham: Springer. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M. F., and R. King. 2021. When migrants become hosts and nonmigrants become mobile: Bangladeshis visiting their friends and relatives in London. Population, Space and Place 27: e2355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miah, M. F., R. King, and A. Lulle. 2022. Visiting migrants: An introduction. Global Networks 23: 150–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miltiades, H. B. 2002. The social and psychological effect of an adult child’s emigration on non-immigrant Asian Indian elderly parents. Journal of Cross-Cultural Gerontology 17: 33–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moscardo, G., P. Pearce, A. Morrison, D. Green, and J. T. O’Leary. 2000. Developing a Typology for Understanding Visiting Friends and Relatives Markets. Journal of Travel Research 38: 251–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]