Abstract

This paper examines secondary rock art practices in southern Africa and how they served as mechanisms for expressing and negotiating identity through iterative engagement with existing artistic traditions. Often dismissed as mere ’graffiti’ or vandalism, these practices of modifying, adding to, or reinterpreting historic rock art represent sophisticated forms of engagement with inherited cultural landscapes. Through detailed analysis of mode, placement, and technique, this article demonstrates how secondary artists used existing imagery as both physical and symbolic resources, selectively mobilising earlier artforms to articulate their own positions within changing social worlds. With their technical choices encoding specific attitudes towards inherited traditions, secondary artists appear as one of many audiences—a range which includes contemporary researchers—engaging with these artistic traditions as subjects of common interest, their modifications creating material epistolaries that capture how different communities understood and positioned themselves relative to their own imaginations of the past. By reconceptualising these practices as meaningful interpretive acts rather than degradation, this paper contributes to broader discussions about how African identities have been articulated, contested, and preserved through active engagement with cultural heritage across time.

1. Introduction

All human movements, even the most violent, imply translations.Deleuze and Guattari (1987, p. 84)

Rock art sites across southern Africa have complex use histories, in some cases spanning millennia from their first production and into more recent eras where their original contents have been embellished, modified, or transformed by an increasing diversity of artists (see Skinner and Challis 2024; also McGranaghan 2016). While destructive interventions are common in their own right (discussion in Laue and Dean 2022), there is reason to be attentive to where legitimate preservation concerns may be leading to a conflation of any post hoc modification with vandalism. This contribution examines the phenomenon of secondary imagemaking in the Maloti–Drakensberg mountains of southern Africa—that is, interpretive modification of existing imageries—and theorises their role in articulating changing identities through changing historical moments.

Objects and places have complex social lives (Appadurai 1986), which resist stasis and isolation, categorisation and decontextualisation (Miller 2005). This resistance comes about not through conscious opposition but in the inherent inseparability of people and their possessions. One can place an object behind glass and see that it lives forever, but in doing so, occlude the meanings that accumulate through use. Objects and places feed memory, and feed upon memory, remaining in our consciousness precisely because they are fora of engagement between multiple moments and perspectives (Rassool 2010, p. 87). There is a “normal life-cycle of commodities, which normally comprises their creation, acquisition, consumption through use and disposal” (Rossi Rognoni 2019, p. 408; citing Kopytoff 1986, pp. 73–77), and thus if we are to understand objects’ lives, we are obliged to understand the ways in which straightforward, tactile interaction can be integral to identity expression and adaptation to changing sociohistorical circumstances. Cultural materials are not inert nor disarticulated in these processes (Peers and Brown 2003), but rather integral participants in the continuous process of meaning- and object-making that embodies humanity’s characteristically intimate, often mutually determining (Malafouris 2013) relationship with our artefacts. In this contribution, I consider some of the theoretical challenges to analysing secondary images and their impacts on our ability to reach into these same life histories. Then, I turn to the formal qualities of the images themselves, considering the ways in which secondary artists mobilised existing imagery as both physical and symbolic resources, selectively engaging with earlier artforms to position themselves within changing social worlds. By examining the mode, placement, and technique of these modifications, we can consider how technical choices encoded specific attitudes towards inherited traditions.

1.1. Rock Art in the Maloti–Drakensberg: Context and Interpretive Traditions

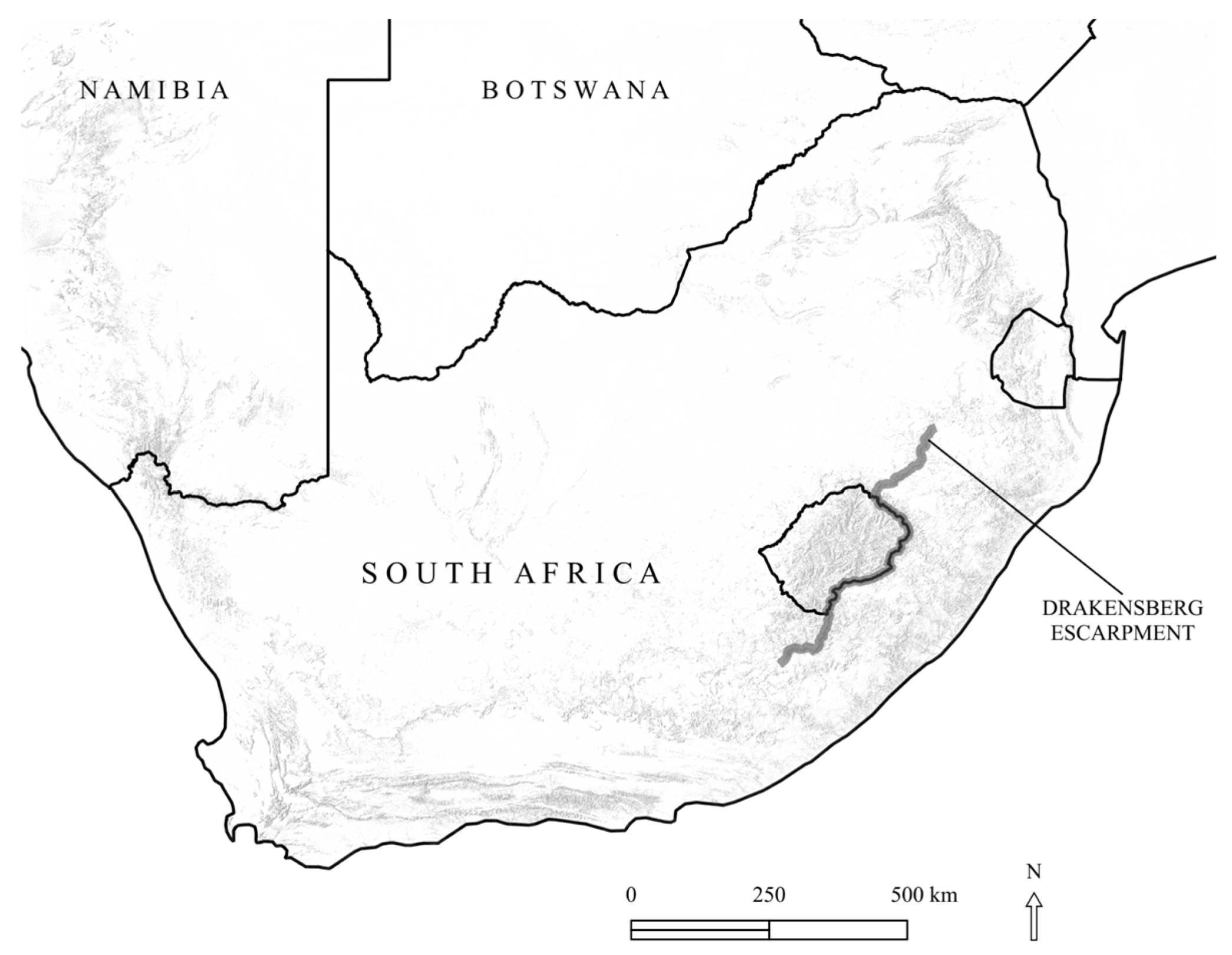

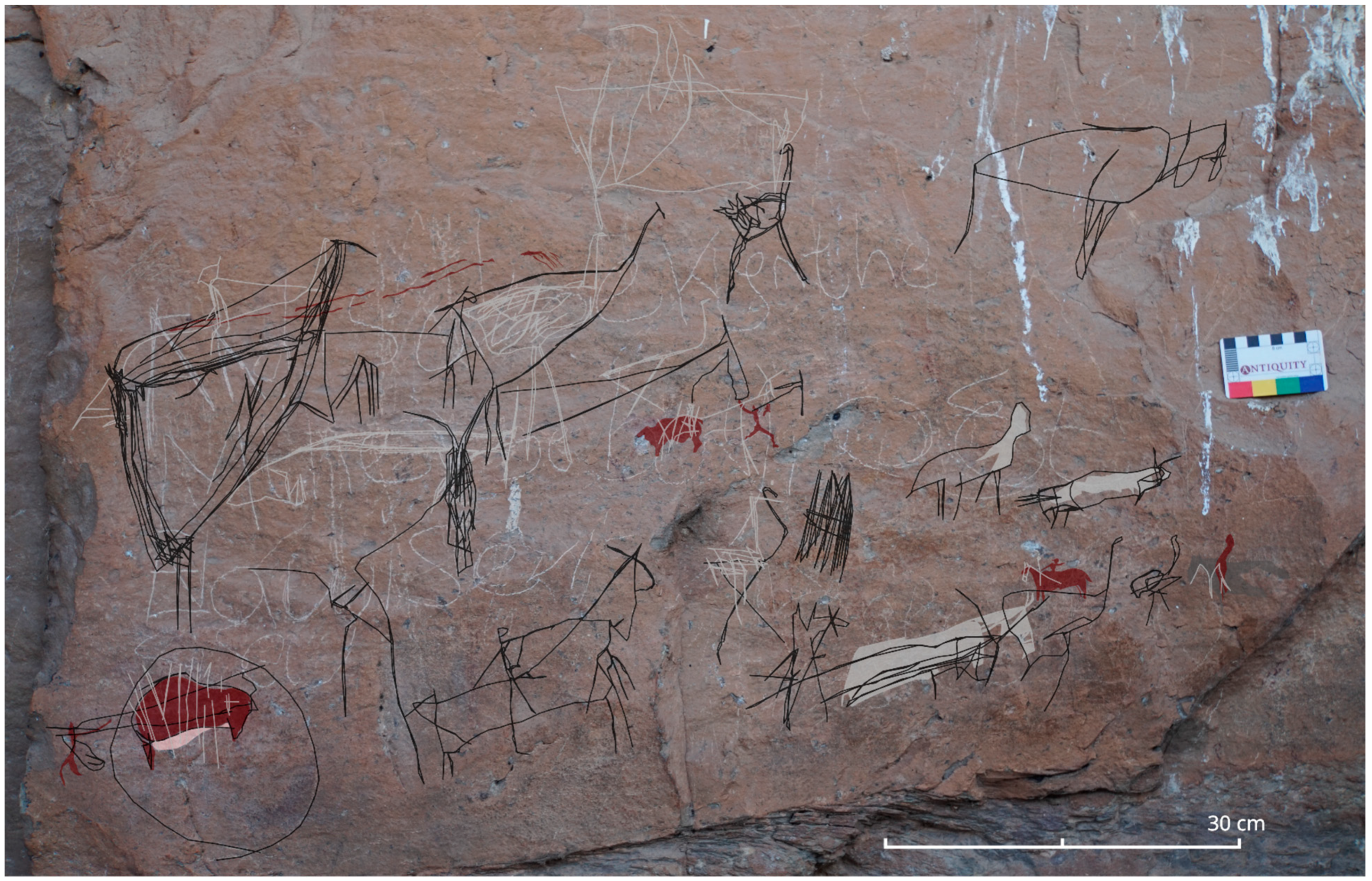

The Maloti–Drakensberg mountains form the southeastern escarpment between South Africa and Lesotho (Figure 1) and contain one of the world’s most significant collections of hunter-gatherer rock art (Hampson 2015, p. 375). This tradition, most commonly associated with Maloti San hunter-gatherers, is characterised by naturalistic and geometric forms executed in fineline, blended brushwork and polychromatic pigments (Vinnicombe 1967, p. 129; see, e.g., Figure 2), and can be found across the subcontinent (Pager 1973; Smits 1983; Challis 2018; discussion in Lewis-Williams 1984), reflecting a widespread practice with both great antiquity (Bonneau et al. 2017) and a terminus within the last two centuries (Challis 2022).

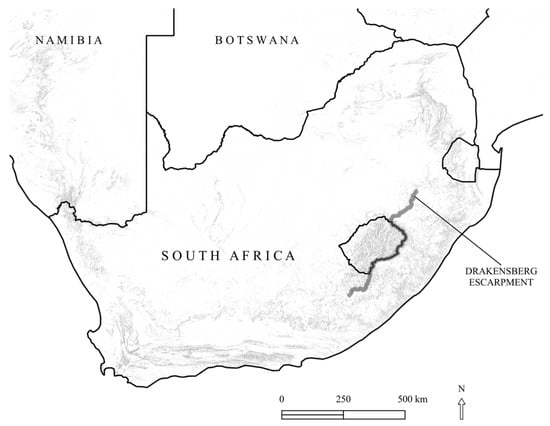

Figure 1.

Regional map showing the Maloti–Drakensberg study area, centred on the Drakensberg escarpment, in and around which much of southern Africa’s San rock art is located. Map by author.

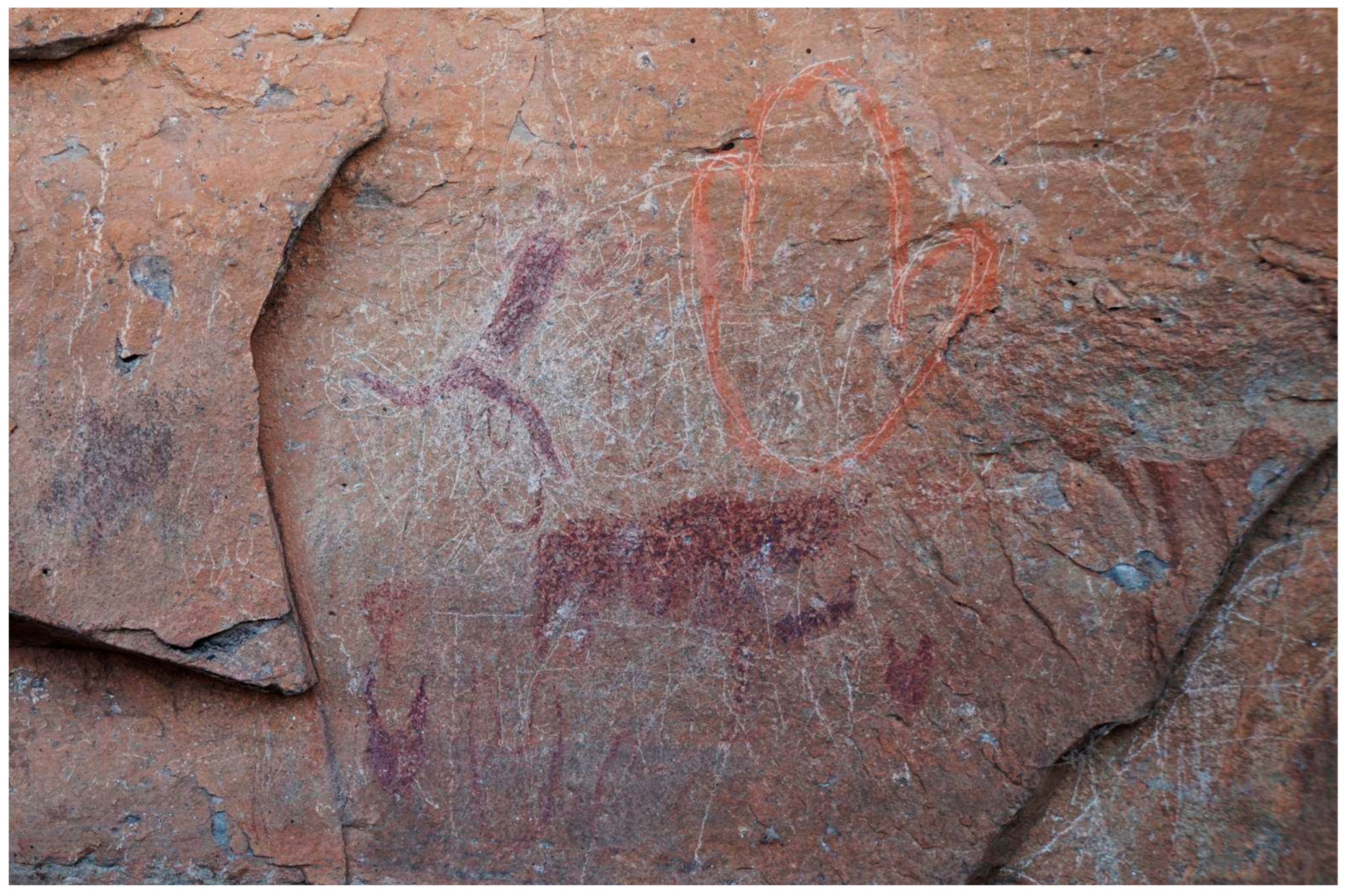

Figure 2.

Illustrative example of a brush-painted ‘traditional’ rock art panel. It depicts stylised human figures in a variety of poses and orientations, and shaded, polychromic antelope. Highland Lesotho, southern Africa. Image courtesy Sam Challis.

Scholarly interpretation typically follows the neuropsychological, shamanistic account (e.g., Lewis-Williams 1980; inter alia), which has been extended into palaeolithic and indigenous arts of other world areas (following Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1988; see Turpin 1994; Dronfield 1996; Lewis-Williams and Clottes 1998; Wallis 2002; inter alia). While this interpretation remains effective, recent scholarship has begun to recognise greater diversities of subject matter and methodology (discussion in Dowson 2009; Challis and Sinclair Thomson 2022), and further developments incorporate broader ontological perspectives aligned with a reevaluation of relational metaphysics (see Dowson 2009; Smith 2010; Skinner 2021; cf. McGranaghan et al. 2013, p. 146; Skinner 2022).

Despite these and other divergences and advancements, there remains a certain selectivity in what receives the bulk of scholarly attention. ’Traditional’ imagery, especially that with overtly ritualistic motifs, tends to attract the most discussion, while the rich diversity of later engagements receives comparatively little analysis beyond their historical narratives (see commentaries in Ouzman and Loubser 2000; Blundell 2004, pp. 62–63; Smith 2010, pp. 350–52; Challis 2016; Skinner 2017, p. 31; Challis and Sinclair Thomson 2022).

These sites are and have always been nodes of quite direct and tangible interaction between bodies and worlds—places where physical and material interaction coexist as a continuous symbolic reinterpretation and incorporation of diverse cultural moments and practices. The materiality of these engagements creates networks of memory and meaning that connect past and present, enabling communities to actively negotiate rather than passively receive their cultural heritage (Edwards et al. 2006, pp. 12–13), even when the details or authorship of such heritage are not always ’accurately’ known either by scholars or communities themselves (cf. Bolton 2003, pp. 49–51). Coupled with the other challenges that face preservation and education efforts, it is sometimes difficult to consider whether permanence or immutability were valued by original creators, instead imposing stasis on expressions whose lifecycles were otherwise bound to daily practice (cf. Hamilakis 2011, p. 408). Southern African artistic traditions themselves demonstrate alternative approaches; inherited forms serve as resources for ongoing processes of identity formation and articulation (Challis and Sinclair Thomson 2022), rarely standing still.

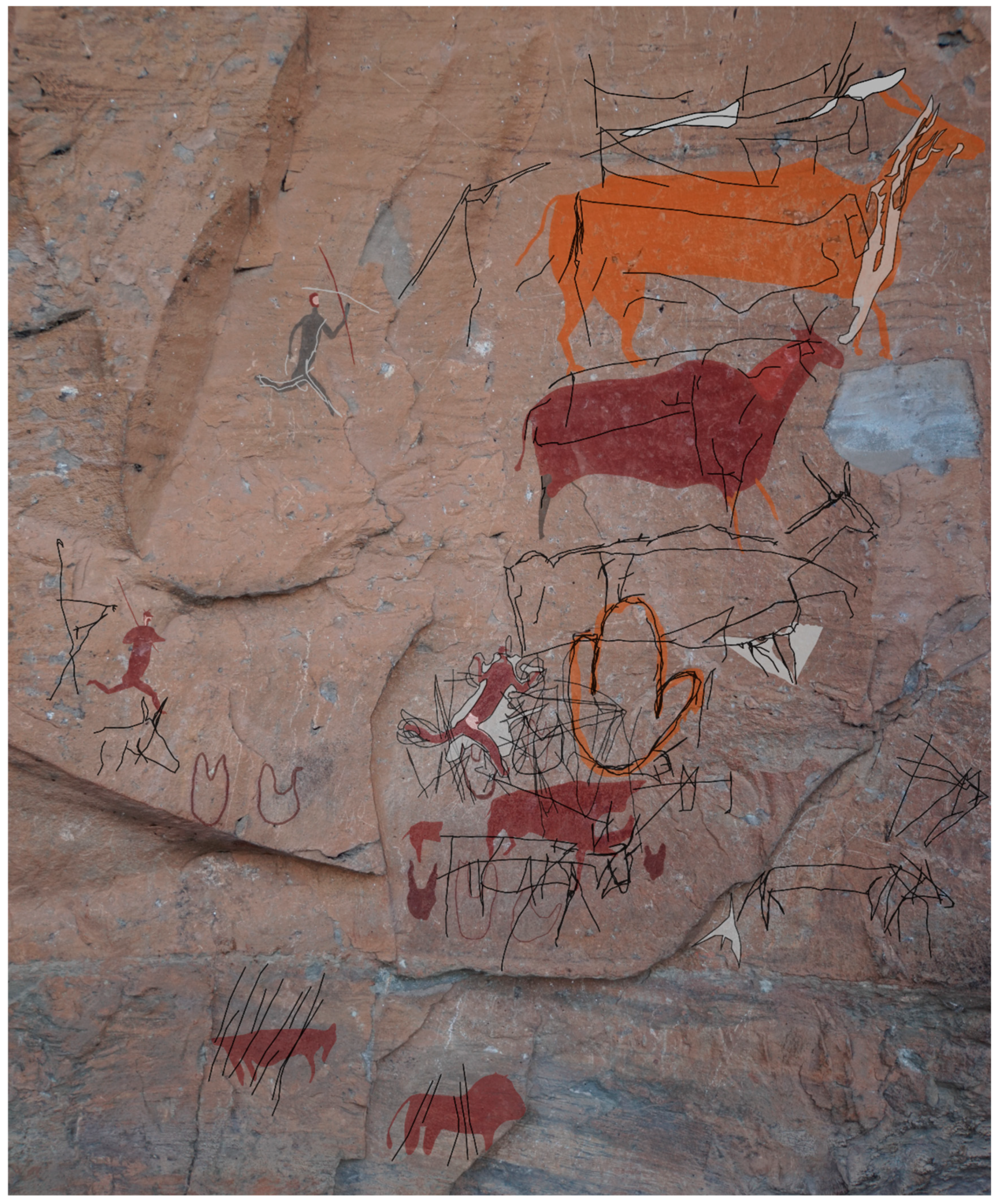

This paper examines interpretive, post hoc engagements in secondary images from the Maloti–Drakensberg (e.g., Figure 3 and Figure 4 after), the nature of these imagemaking practices themselves and their consequences for interpretation. It begins by considering the effects of the terminologies which conventionally frame these practices and their impacts on our understanding of their potential cultural significance. From there, it develops the notion of ’iteration’ as a framework for understanding the practice as an interpretive, iterative engagement with artistic heritage and the imagination of history by historic peoples themselves. From there, specific case studies consider the effects of mode, placement and technique, with attention to how specific technical choices—whether ephemeral enhancement, selective modification, or more whole-cloth transformation—carry their own semantic content and encode attitudes towards inherited traditions. This goes towards a broader re-imagining of the practice and the differentiation of interpretive actions—whether additive or reductive—from more intentionally destructive, acultural ones. The intent is to demonstrate how these actions can be read as the active shaping of cultural inheritance through ongoing interpretive processes.

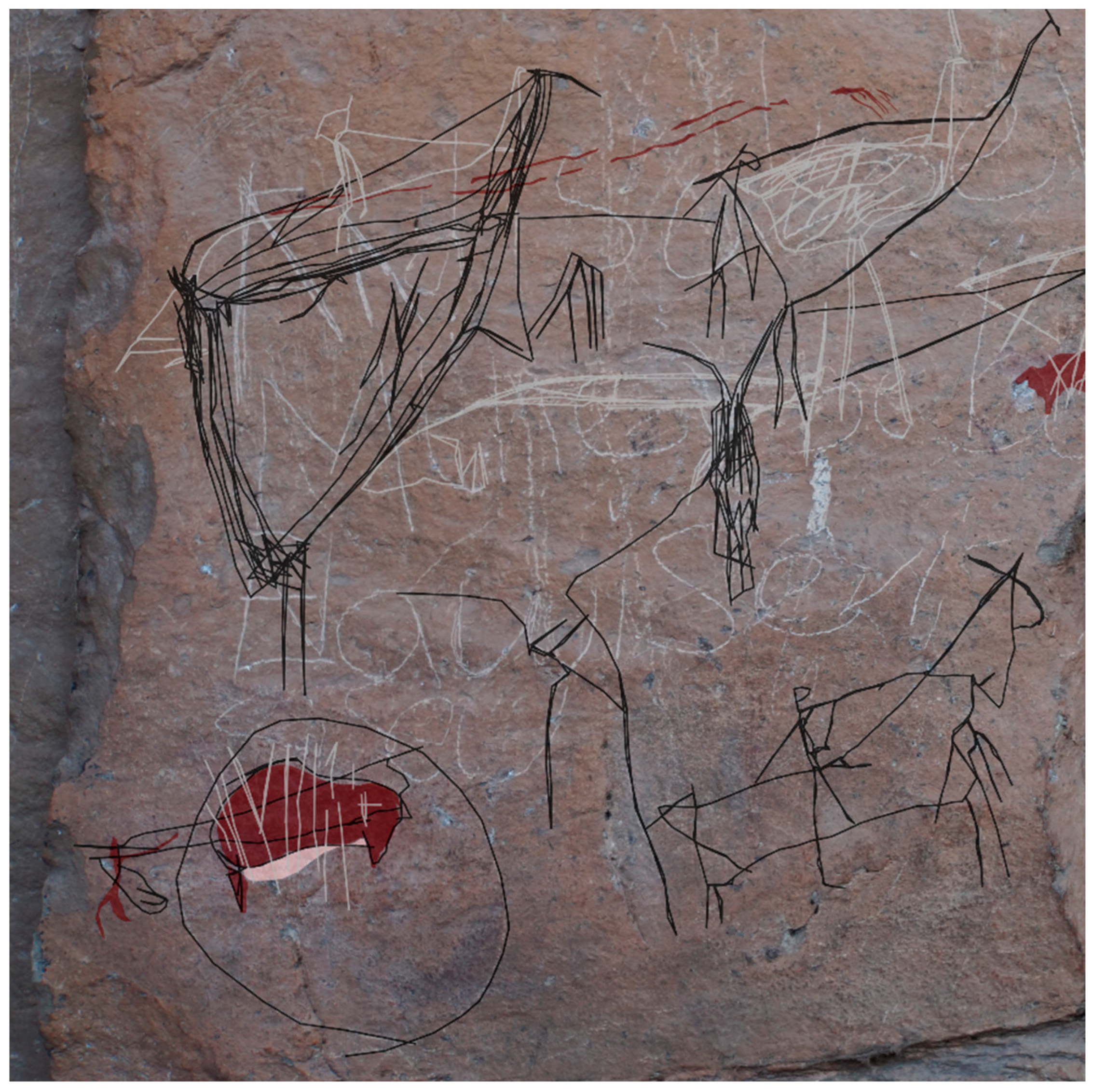

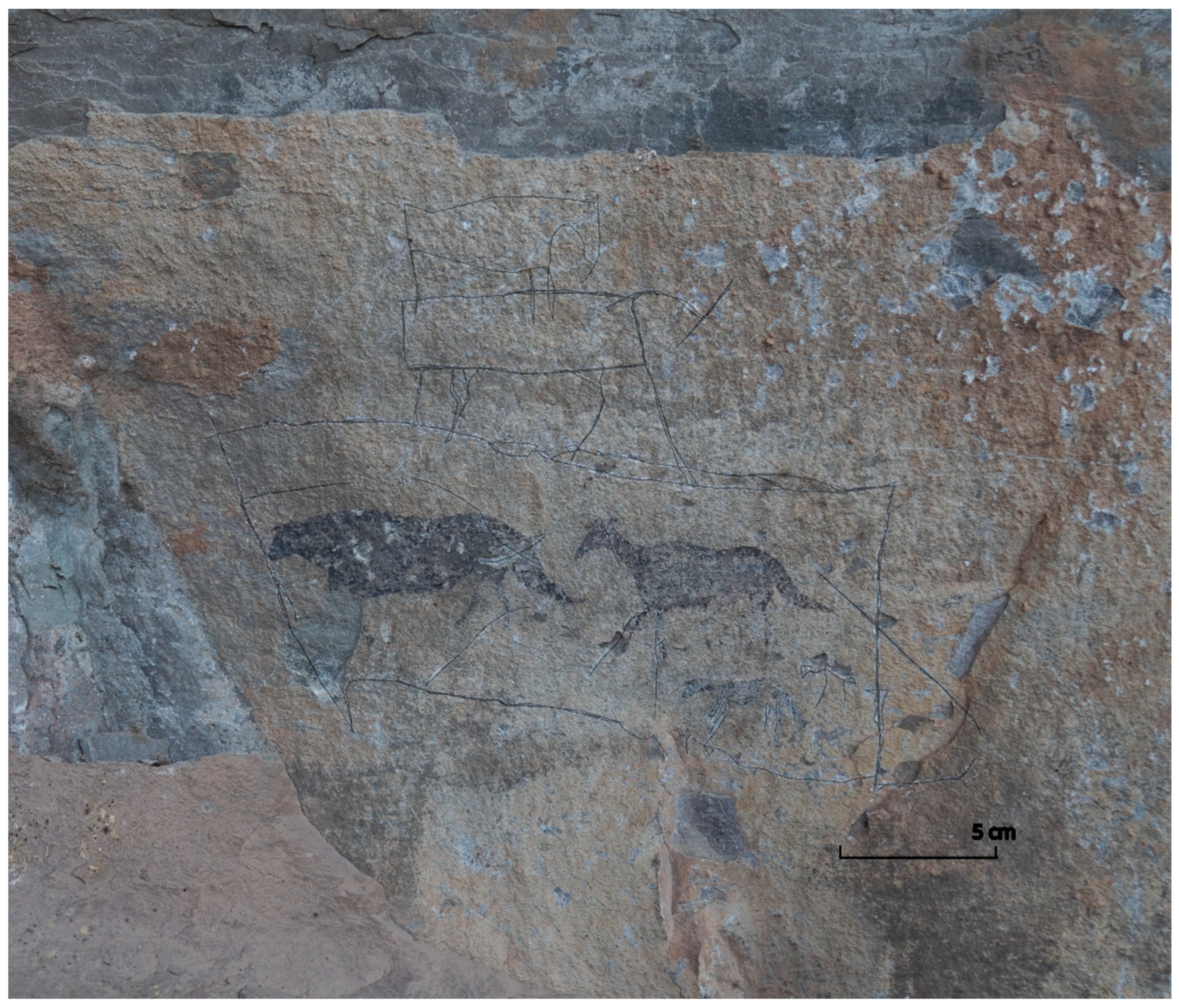

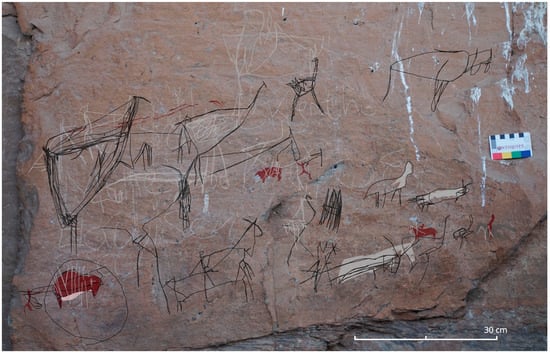

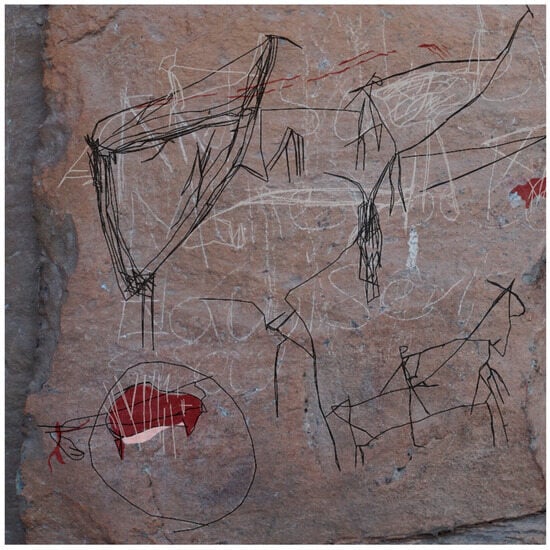

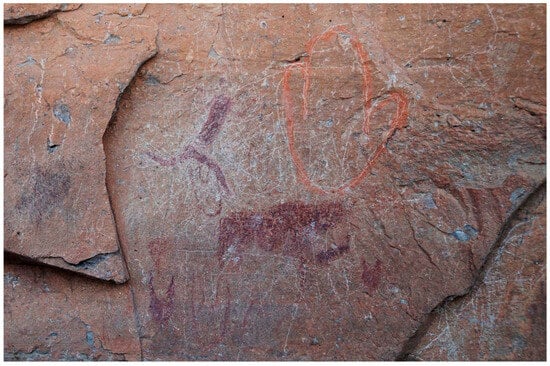

Figure 3.

Extensive engraved modifications and additions to existing ’traditional’ and contact-era paintings, Highland Lesotho. Image and trace by author.

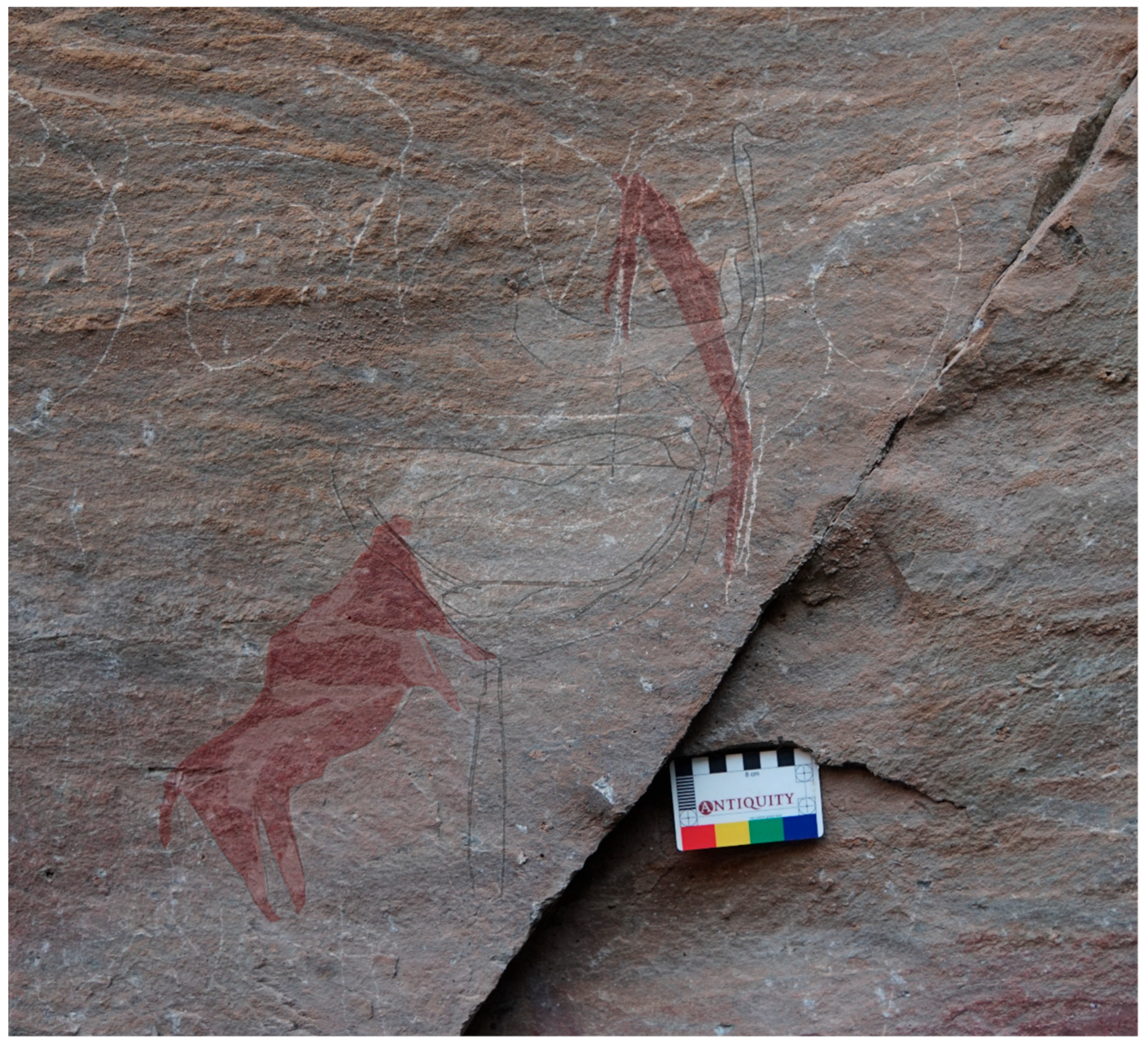

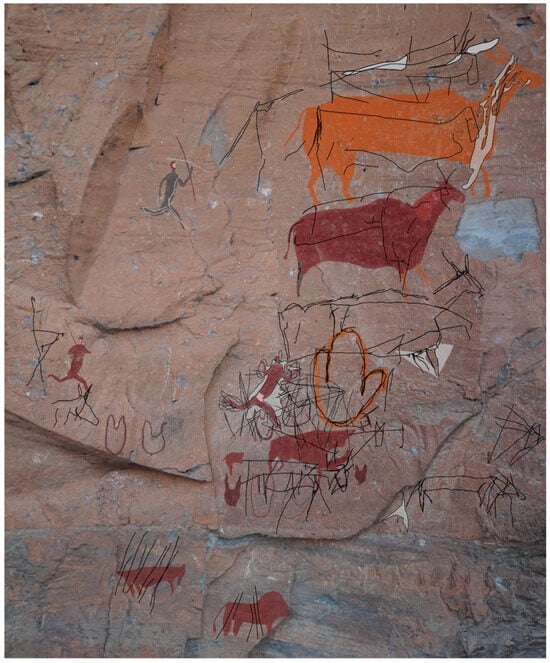

Figure 4.

Extensive modifications, enhancements, and duplication of painted imagery, Highland Lesotho. Note the duplication and modification of painted eland (Taurotragus oryx), top right, in three registers: original (red), ’post-disconnect’ (sensu Challis and Sinclair Thomson 2022) chalky pigment (yellow), and scratched/incised engraving (black line). Image and trace by author.

1.2. Terminology and Framing

Choosing words to frame and describe these phenomena poses a distinct epistemological challenge. Even without a regional focus, they tend to be ‘feral’, defying or challenging classification (Ouzman 2019, p. 208), even if giving such diverse material expressions would go some way to establishing greater legitimacy as artefacts (Navratilova 2023, p. 332). The trouble, as Harmanşah (2017, p. 51) notes, is that these images oscillate between multiple interpretive poles—monument and vandalism, cultural continuity and rupture, meaningful engagement and destructive interference. The terms we use fundamentally shape what we observe and which features we consider significant (Tilley 1999, p. 76). For example, the common usage of ’vandalism’ or ’defacement’ focuses attention on issues of preservation and authenticity, while something like ’modification’ is both more neutral, suggesting ongoing and iterative processes, but also less descriptive. In this way, any terminological choice would highlight or obscure different aspects not only of the practices but of our assessments of them.

At once, it is important to make certain distinctions early. There can be deliberate engagement with the meaning and form of underlying images, which can be characterised as enhancement, transformation and recontextualisation. Transformation also occurs in overtly destructive interventions (bullet holes being a notable example; see Mol et al. 2017), but this does not leave much room for interpretation beyond an intent to primarily negate or erase earlier cultural expressions. While both types of engagement reflect cultural attitudes, I focus here on interpretive modifications, where there is potential to discern dialogues between primary and secondary artists via certain indications of selectivity—of choices to respond to, emphasise, transform or incorporate specific elements of old symbolic content into new. Such a distinction is not simply a matter of preservationist value but of recognising the potential for varying modes and degrees of encultured or acultural engagement with the imagery.

In any event, it remains that ’graffiti’ will likely be the most common descriptor of these practices. Even in analytical contexts, the term may struggle with its popular implications; it can come close to ’vandalism’ by some Western intuitions, even if indigenous or descendent artists and audiences may apply different standards to the reuse or instrumentalisation of art and artefacts (e.g., Brady et al. 2021, pp. 15–16; discussion in Merrill 2011). Even carrying the negative inflexion of the term, as accords with the illicit status it has acquired in modern eras, ’graffiti’ can still be a useful analogy to rock art in general. In its guise as ’tagging’ (cf. Merrill 2011, pp. 66–68), it territorialises urban spaces and connects them to specific and highly expressive articulations of identity, “answering a natural impetus for humans to appropriate their environments symbolically”. As additions, in the context of secondary imagemaking, such images penetrate “what they comment on, discuss, adorn and deface [altering] the balance and centres of gravity of the original” (Ragazzoli et al. 2018, p. 10). As modifications, they deconstruct original articulations of territory through the representation of new presences on the landscape (Harmanşah 2017, p. 57), reterritorialising a site (Deleuze and Guattari 1987, p. 316) by making reference to both its origin state and its current circumstances, drawing different temporal territories into a common spatial one.

While ’graffiti’ can imply something ’derivative’ or ’auxiliary’ (Navratilova 2023, p. 332), it remains a commentary with its own biographical and contextual elements and, in addition, one integral to the life of the site. In this respect, the term is both apt and problematic. It foregrounds the transgressive nature of these engagements, particularly in an analytical frame that tends to emphasise highly formalised ritual practices and which sometimes struggles to accommodate more ephemeral aspects of human material engagements (Langley and Litster 2018; Goldhahn et al. 2020). It situates the practice as a subversive one, perhaps to the point of occluding deeper meanings (discussion in Forssman and Louw 2016), although it may usefully imply exactly such a subversion of original identities, contexts and meanings.

An alternative term is ’secondary epigraphy’, which has precedent as a description of monumental inscriptions in Egypt (Navratilova 2023, p. 324), typically taken to mean figurative and written additions external (thus, ’secondary’) to a monument’s original (’primary’) context (Pawlikowska-Gwiazda 2021, p. 139). ’Epigraphy’ here reflects the typical treatment of the marks as textual sources, referring to the archaeological study of epigrams (inscriptions; see Bodel 2001). That said, there is a growing acknowledgement, even in primarily textual settings, that researchers should exercise caution when casting secondary images as a subcategory of historical inscriptions (Ragazzoli et al. 2018, pp. 9–10), as this would obscure the aesthetic and pictorial elements which render them so distinct. While authors have worked to expand its reach (Ragazzoli et al. 2018), the usefulness of the term in southern Africa is impacted by its established uses elsewhere, while the allusion to inscription risks overemphasising written and historical forms. As a terminological device, however, there may be a benefit to following exactly the redefinition underway, interfacing the study of regional secondary images with that of other world areas.

A less obvious term might be ’patina’ (following Dawdy 2016). While some might approach the term with unease (Harmanşah 2017, p. 57), owing to its positioning of an image as an element of later contexts, coming “after that fact, long after the social space has already been created and established, an inherently late response produced by a fragmentary present articulating a long-lost nostalgic whole”. At once, the term does this no less than ’secondary epigraphy’ does, while having notable consequences for its heritage status. It is rarely ethical to remove patinas from archaeological objects (Watkinson 2010, p. 3326), as they are considered the surface layers of otherwise indivisible objects. In some ways, contra Harmanşah’s reservations, the term in archaeological contexts implies a unity of primary and secondary strata, foregrounding their common composition and overtly recognising later changes to the context and lifecycles of heritage objects.

A final consideration is to simply re-ambiguate secondary images under ’rock art’, albeit with an explicit carve-out for latter-day, encultured imagemaking practices. ’Graffiti’ can be troublesome because of what it draws in value-orientated distinctions between authentic, primary images and inauthentic, secondary ones. It can be useful in capturing territorial and transformative aspects of identity expression but risks obscuring deeper meanings. ’Secondary epigraphy’ emphasises the interpretive and citational nature of the practices but may shift emphasis to inscriptional content, following its more established uses elsewhere. ’Patina’ recognises some of the deeper and more tangible overlaps but does not necessarily call to mind the intentional nature of the practice. ’Rock art’ has challenges of its own; it has its own established tendencies and, particularly in southern Africa, tends to revert to a ritual focus even if there may be other ambiguities (McGranaghan 2012, p. 202; Guenther 2020, p. 258; also Gunn et al. 2022, p. 21), and generally struggles to accommodate anomalous occurrences, particularly when interpretive limitations may instead be read as inauthenticity on the part of the subject (discussion in Skinner 2021).

In this paper, I use ’secondary imagemaking’ for its relative neutrality, attempting to strike a balance between signalling the temporal/contextual distance while recognising that these practices are active, intentional expressions rather than passive accumulations. As it is imagemaking, it also presents a constructive distinction with comparatively acultural, overtly destructive interventions—as with the bullet holes example—dwelling instead on what there is to interpret in figurative practices. The choice also supports the framework of ’iteration’, developed below, as it captures the ongoing and transformative nature of these engagements, hinting at their cultural content and interpretive potential.

2. Iteration: A Theoretical Framework

Central to this analysis is iteration, but not simply as repetition or modification. Secondary artists engaged in complex processes of selective interpretation, with each moment of engagement capturing a snapshot of specific social attitudes and perspectives at a given moment along the lifecycle of the arts which came before and after them. The choices made in these moments—which images to engage with, how to transform them, what to emphasise or obscure—reveal their attitudes.

Just as individuals draw on cultural repertoires to express identity in response to social context (Spitzer 2003, p. 58), secondary artists chose particular images as substrates for novel expressions, drawing on their understanding of place, practice, and the cultural cachet of existing artistic traditions—a cachet which itself was not dependent on emic understanding of those traditions themselves. Rather, just as a craftsperson selects specific materials for their physical properties and contribution to an intended creation, secondary artists selected imagistic substrates as ’material’ for theirs, although here the materials carried social and metaphorical contents (Thomas 1991, pp. 4–7; Tilley 1999, p. 76). In this, existing imagery served as both physical and symbolic resource, with secondary images acting as intertextual exercises on the parts of their artists (Jones 2007, pp. 62–65). The selection and transformation of existing imagery thus becomes a form of material engagement (Malafouris 2013), where object biographies serve human ones through commentary written from ’inside’ successor practices.

This contrasts existing scholarship, which may, intentionally or otherwise, emphasise rupture, hiatus and discontinuity in African histories (discussion King 2024), and instead reveals ongoing processes of engagement and transformation into, in some cases, the very near present. Taking a view of interpretive modification as dialogue rather than degradation, these practices come to represent a form of communication across time, a certain animate humanity showing through comprehensible practice (Harmanşah 2017, p. 51). Each mark, each modification, serves as an epistolary trace—evidence of how past communities interpreted and expressed specific views of their own histories (Parkinson 2009, pp. 40–42).

This approach has a kinship with archaeological ethnography (Hamilakis 2011, p. 401), positioning secondary artists as independent observers of the same archaeological materials that are the subject of our common interest, with their expressions acting simultaneously as artefact and commentary. Through a distinctly socialised material engagement with existing imagery (Malafouris 2013, p. 44), they allowed “the values of things [to] become entangled with stories about their sources” (Thomas 1991, p. 103); through this distinct ’reauthorship’ (Thomas 1991, p. 5), secondary artists were not passive recipients of received tradition, but active interpreters (Jones 2007, p. 62). The changing interpretative processes which manifest in their particular technical choices indicate changing outlooks and material conditions (Ingold 2013, pp. 20–21), which means that rock art and other signatures of peoples from the more distant past, rather than simply persisting, remained ’alive’ into the more recent past, and indeed the near present, in ways which their successors found significant.

At once, it is worth acknowledging that the depth of engagement in secondary imagemaking likely varies considerably, just as it does in primary ones. Not all secondary artists necessarily approached their modifications with equal degrees of intentionality or symbolic awareness. We can recognise a spectrum, however, from deeply considered symbolic interventions to more expedient, perhaps even incidental, ones. It remains that there was a choice to engage with specific images, regardless of fully conscious articulation of meaning, which reveals attitudes towards primary images that operated at both conscious and implicit levels. The framework presented here is intended to draw attention to this selectivity and the meaning potentials that go beyond random marking or apparent vandalism.

3. Case Studies: Secondary Imagemaking as Interpretive Practice

To demonstrate the interpretive processes that characterise secondary imagemaking, this section examines examples from Highland Lesotho that illustrate different forms of engagement with existing rock art. Each considers how the technical choices made by secondary artists—their selection of medium, placement, and mode of interaction with primary images—give a sense of their attitudes towards inherited imagery. Notably, the processes manifest not only in the images’ formal qualities but also in the embodied experiences the associated qualities represent. Secondary imagemaking is both a semiotic and tactile exercise, with a choice between additive practices (such as applying charcoal or pigment) and subtractive ones (such as engraving, rubbing or incising; following Gunn et al. 2022), then further devolving into incision, chipping and rubbing, each of which has notably different embodied characters and different implied attitudes to underlying substrates. For example, rubbing can be a measure of both additive and subtractive, given that it simultaneously patinates and abrades the image(s) involved. The embodied experience of this mode has a significant embodied and affective dimension, involving and invoking touch in the process (Dowson 2009, p. 381; Goldhahn et al. 2020, pp. 75–76). Engravings involve some form of surface removal at a minimum, but the physical amount of material removed can be disproportionately smaller than the symbolism it adds. Even the chipping of pigments to remove them, the most overtly subtractive of these processes, reveals elements of how images were incorporated into descendent practice and ideology (cf. Motta 2019, pp. 492–93).

For terminology, I draw on typologies and reasoning developed by Brady and colleagues (Brady et al. 2021, pp. 6–7), who in turn develop on that of Sale (1995). They start with ’re-marking’ and, from there, distinguish intensities of engagement, ranging from ’retouching’ (cosmetic embellishment), through ’alteration’ (changing image form or content), to more substantial ’amendment’ (transformation of whole images; citing Gunn 2019, p. 90), ’retouch by scarring’ (full or partial occlusion or removal of the image) and culminating in ’erasure’ (obliteration of the primary image; see Mulvaney 2009). Similarly, Delannoy and colleagues (Delannoy et al. 2018, pp. 834–35) build on earlier modelling by Motta (2019, pp. 479–80, citing Battiss 1939) to consider the impacts of placement. Secondary artists could mark anywhere, but placing their contributions over or near existing images points to conspicuous intentionality. From this, we may observe that superposition (placing one image over another) uses the primary image to contextualise the secondary, narrowing its range of potential meanings by connecting it to the significance of its substrate. Superimposition, partly by contrast, involves some degree of rework of a primary image, creating a unitary composite that transforms the meaning of the original as part of work towards a new meaning in the secondary one.

Some degree of the artists’ intents can be inferred accordingly. Superposition uses a primary image to contextualise the secondary and can be understood in the same way that substrates (cf. Lewis-Williams and Dowson 1990; Lewis-Williams 1998) and wider landscapes (Motta et al. 2020; Challis and Skinner 2021; Skinner and Challis 2022) typically are. An image has a range of potential meanings, but by its position within a specific context, has those meanings narrowed to those which reflect the significance of its substrate and, respectively, the substrate’s position as part of a wider “inscribed landscape” (Motta et al. 2020, p. 139). The process is mutually constitutive; a substrate comes to have its significance and context altered by being something upon and through which other symbolic expressions are made. Superimposition heightens this change; the secondary artist has some perspective of the primary symbol, based on their own models of significance, which they call upon to compose something new. A related dimension to this is the selection of common substrates without a specific overlay of secondary images over primary (see below), in which latter-day images are placed onto the same rock surfaces without directly interfering with those that defined the site initially. Of all possible placement opportunities, the choice to reutilise the same place—and thus to play a part in its continuing (re)definition—reflects a model of significance in and of the landscape to secondary artists, upon which existing imageries were nodes of value.

The tactility and selectivity of these actions go some way to signalling secondary artists’ priorities (following Ross and Davidson 2006, p. 324; Jones and May 2015, p. 65; Brady et al. 2021, p. 8), with choices and interventions serving as maintenance (Mulvaney 2009), reference (O’Connor et al. 2013, p. 549), recursion (Motta et al. 2020), revision (Wallis 2009), repurpose (Pawlikowska-Gwiazda 2021, p. 158), and contestation (Harmanşah 2017; Brady et al. 2021, p. 16). Modal interactions can be taken for their implied social relations, with maintenance, for example, signalling the relative importance of the primary symbol in a secondary context, potentially with respect to the value of the primary image as social and/or ritual leverage in a subsequent moment (cf. Challis 2014). From there, the spectrum of modification to obliteration points to desires to do everything from invoking earlier signs of presence, changing older marks to fit new conditions, relating to, taking in or denying earlier essences.

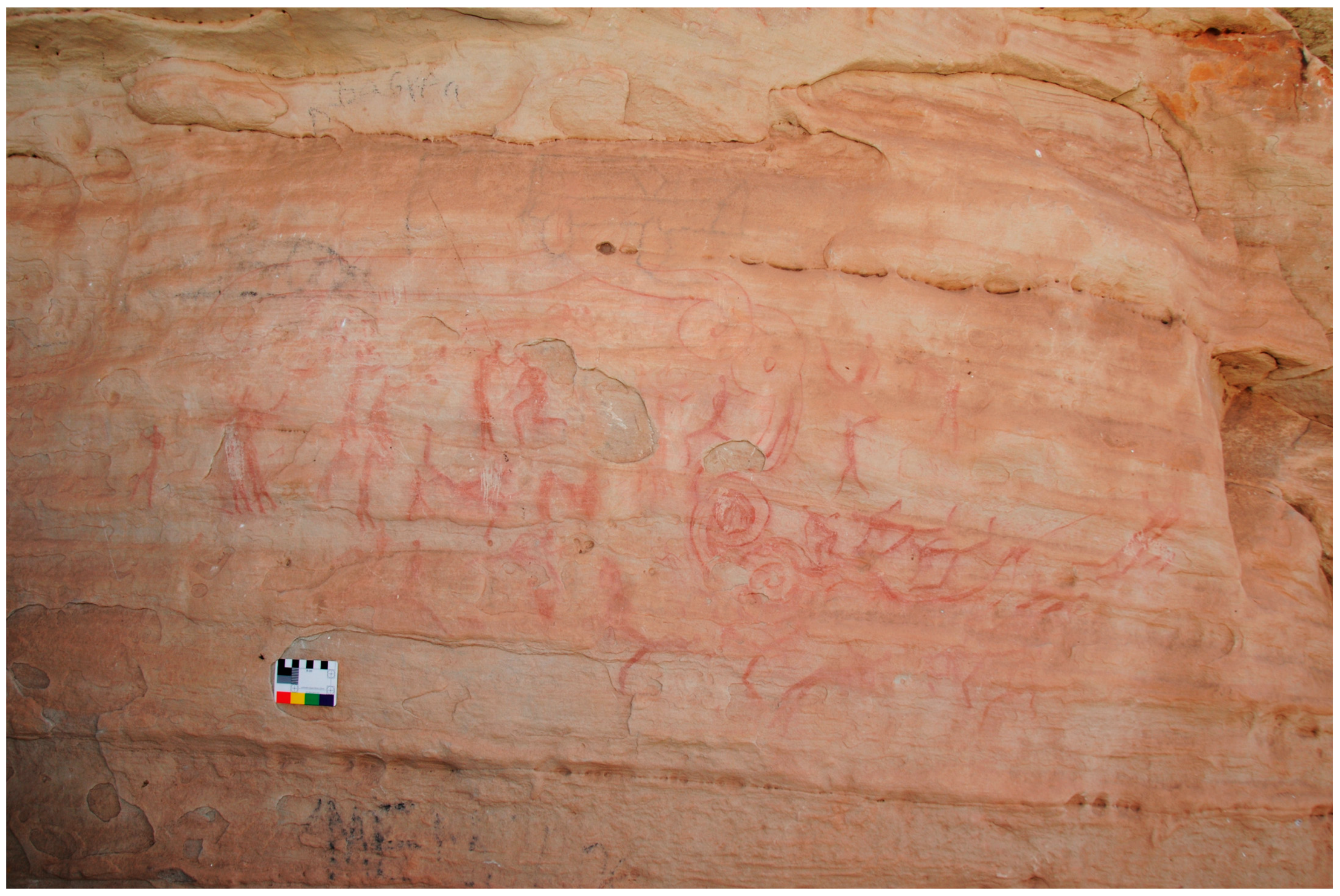

3.1. Case Study 1: Annotations and Marginalia at Rain Snake Shelter, Lesotho

The first example comes from Rain Snake Shelter, which contains a well-known primary panel (Figure 5; see Skinner and Challis 2022) depicting a large, coiling serpent and numerous human figures rendered in brush-painted, red ochre pigment. A number of faded charcoal additions are visible just above and below the primary image, although this is not the main form of secondary modifications at the site. A number of charcoal (Figure 6 and Figure 7) and abraded (Figure 8) additions have been made at the margins, following the main sandstone formation which holds the primary image.

Figure 5.

Main panel at Rain Snake Shelter (RSS), Highland Lesotho. Note pigment abrasions and removals (centre left), and charcoal additions (top left, bottom left). Image by author.

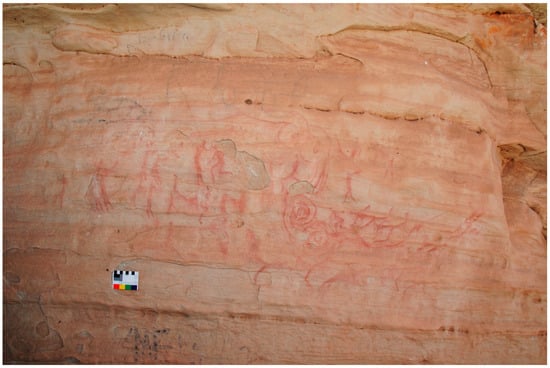

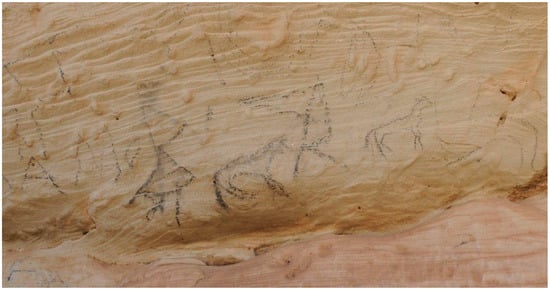

Figure 6.

Charcoal horse and rider at RSS, Lesotho. Image by author.

Figure 7.

Charcoal human and animal figures at RSS, Lesotho. Image by author.

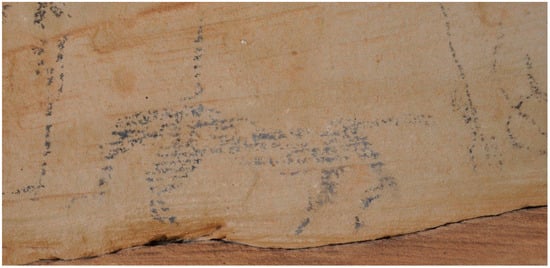

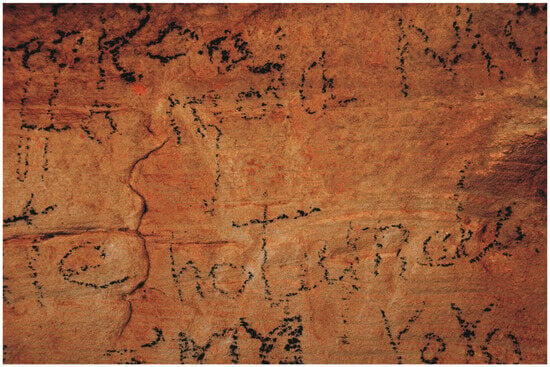

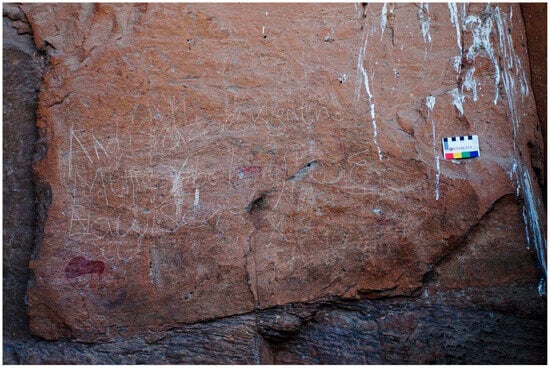

Figure 8.

Abraded horse (with antelope horns) and rider, charcoal lettering at RSS, Lesotho. Image by author.

These choices of medium have a notable ephemerality. Charcoal, without the pigment binders that characterise black paint in ’traditional’ imagery, fades very rapidly, and the shelter’s narrow overhang offers relatively limited protection from the elements. This affects the abraded images as well, as the sandstone substrate is quite soft and vulnerable to weathering, the effect of which is similarly visible in the faded red ochre panel (Figure 5). This indicates that the secondary images are of a relatively young age, minimally less than the approximately 190-year window following the arrival of horses in the region (Challis 2008), but likely far less than this. What they do speak to is the contingency of the practice; secondary artists reached for pieces of charcoal and stone to add to or abrade the surface, engaging in a form of temporary or accessory engagement rather than permanently modifying the primary images. While the site is narrow and confined, it is fairly long (>40 m) and surrounded by sandstone formations which would be equally, if not more, suited to imagemaking.

What the site demonstrates is a continuity of significance, both of place and practice. The images could have been placed elsewhere, but they are directly connected to a specific panel, where secondary artists could reproduce the act of imagemaking in a place already rendered significant by the imagemaking of prior populations, potentially beyond the reach of memory. To fit with Brady et al.’s (2021, pp. 6–7) typology, these might be considered ’retouches’, cosmetic embellishments which function to bring motifs (horses, in particular) from a distinctive moment into a common context with much older ones.

However, there are other non-imagistic signs of either direct or invoked ideological continuity. On a part of the sandstone formation which bears the ’Rain Snake’, there are a number of abraded grooves (Figure 9), a phenomenon historically documented as ’spear-sharpening grooves’ (see Hollmann 2007, p. 144), but which likely have more complex, ontological explanations (see Skinner and Challis 2022). In either event, these too have been replicated, although with metal implements (Figure 10), with their differences in age visible in the repatination and edge-weathering of one set (Figure 9) relative to the others, which appear to have been made with a hacksaw (Figure 10). A parallel explanation could be the removal of the substrate for perceived medicinal or spiritual value. In either case, there is an indication of a perceived continuity of significance tied to the place—there is something about coming to the site and (re)performing the activities that previously defined the site and that continue to do so for descendent communities. This, in turn, is suggestive of the significance of the secondary images; they have been annotated and/or retouched in acts that replicate those of imagined predecessors, albeit taking latter-day symbols and tools into a common context with those of past populations.

Figure 9.

Cut marks on the sandstone ‘step’ below the formation that holds the main panel at RSS, Lesotho. Image courtesy Sam Challis.

Figure 10.

Sandstone removal, made with what appears to be a hacksaw, from the same formation as in Figure 9 above. RSS, Lesotho. Image courtesy Sam Challis.

These and other kinds of either ’light touch’ or proximal additions have been documented elsewhere (e.g., Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13) and are likely amongst the most common interpretive modifications. People are returning to nodes of salient history and taking part in the activities that define those places for themselves at that moment, with at least some care for replicating their perception of prior acts. These latter acts are commentary in themselves, indicating an account of enduring significance, likely as part of an articulation of individual heritage. This has precedent in the region, with historic, creolised groups like the AmaTola (see Challis 2012, 2014) performatively taking on San ritual and imagemaking practices with the specific intent of referencing those aspects of their origins. While ascertainable links between contemporary communities and San heritage are complex and often implicit rather than explicit, the persistence of certain practices speaks to communities operating with a more nuanced understanding of cultural inheritance than overt identification would suggest. The contemporary setting has few who overtly claim San heritage, even if regional genetics speak to complex histories of admixture (Daniels et al. 2023), overlapping and integrating terminal phases of populations more robustly tied to longer-term, primary imagemaking. However, cultural continuity in this setting operates less as a binary state than as a spectrum of engagement with inherited heritage landscapes, less through conscious claims to specific genealogies and more through persistent engagement with significant places and creative practices.

Figure 11.

Location of abraded horse (detail in Figure 12 below), just above protective fencing at a painted rock art site in the Free State, South Africa.

Figure 12.

Detail of abraded horse, expediently produced, above protected site in the Free State, South Africa.

Figure 13.

Minor scratched and charcoal amendments to traditional images, Sebapala River Valley, Highland Lesotho.

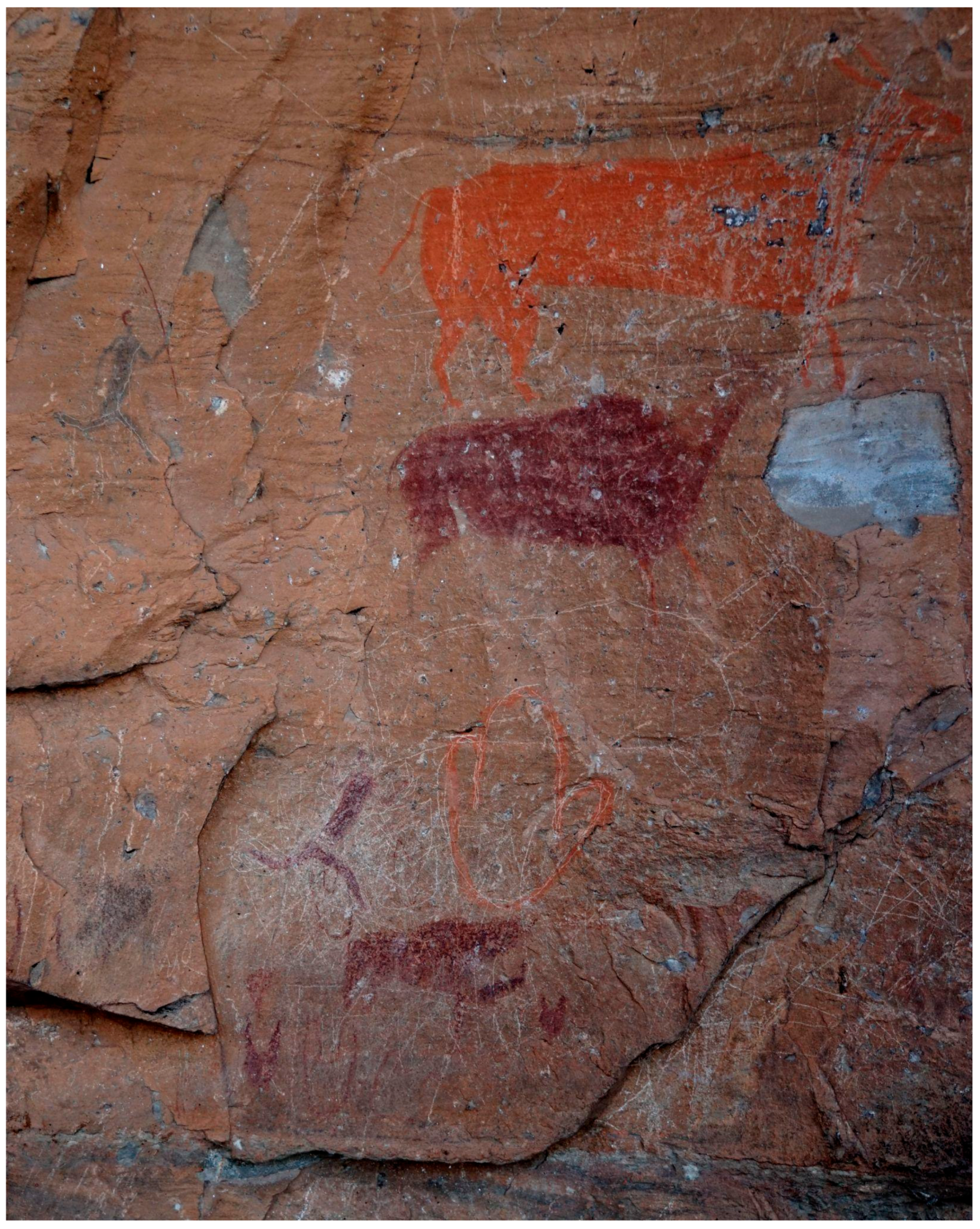

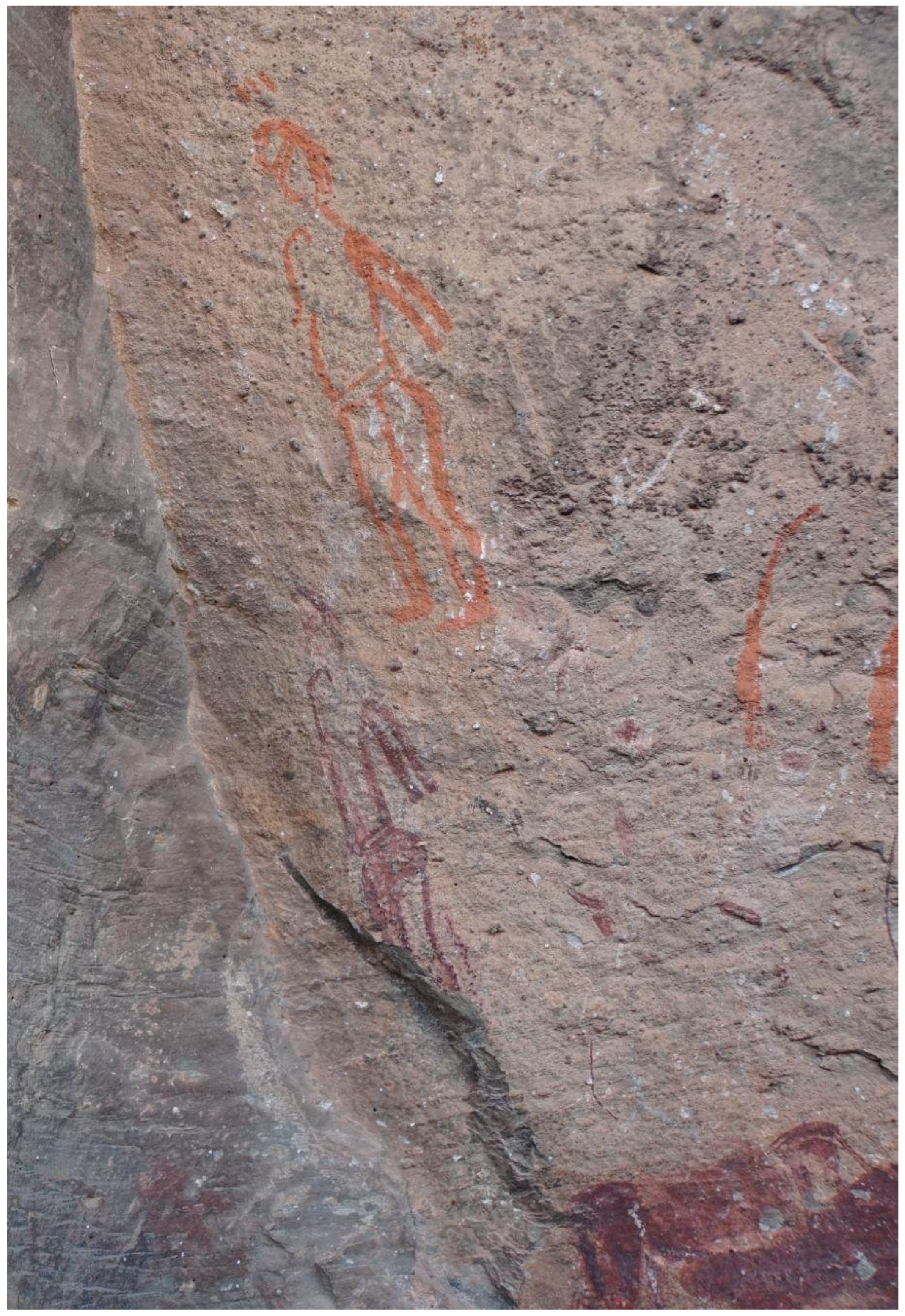

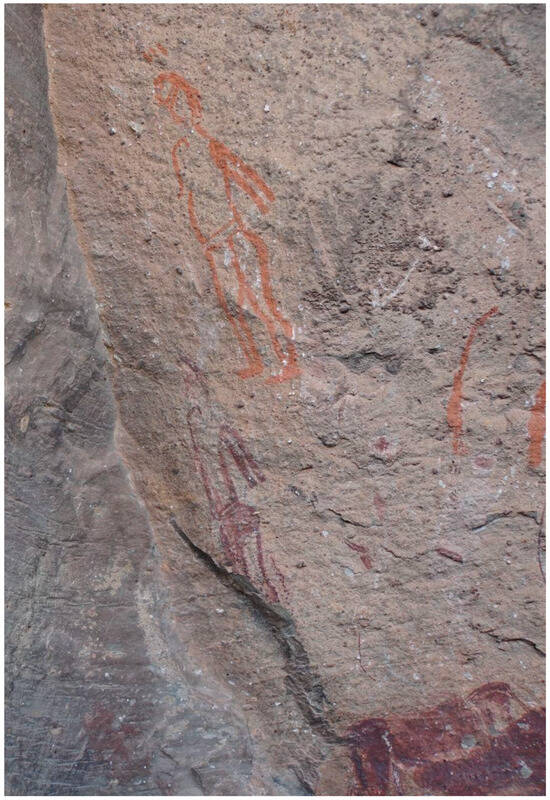

3.2. Case Study 2: Reconfigurations and Repetitions at Khomo Patsoa, Highland Lesotho

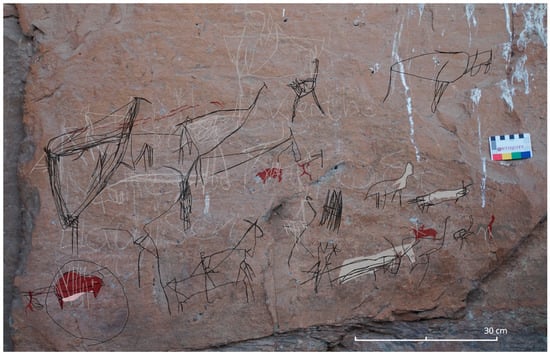

A far more heavily modified site is Khomo Patsoa, a very large shelter in Highland Lesotho that possesses an extensive assemblage of images, both primary and secondary, spanning more traditional, colonial-era, and latterly scratched and painted secondary images. Much of this (e.g., Figure 14 and Figure 15) would qualify as alteration and retouch by scarring following Brady et al.’s (2021) typology and includes significant superimposition (in the sense used by Delannoy et al. 2018), in which secondary overlays conspicuously change aspects of primary images (for a more complete catalogue, see Skinner and Challis 2024).

Figure 14.

Extensive modifications to a main panel at Khomo Patsoa, Highland Lesotho. Base image courtesy Sam Challis; tracing by author.

Figure 15.

Base image, showing extensive modifications to a main panel at Khomo Patsoa, Highland Lesotho. Image courtesy Sam Challis.

Here, the modification of primary images is more pronounced than at RSS, with one notable example of a poorly preserved eland being ’cut’ several times over, with long and fairly deep strokes being drawn across its body (Figure 16, bottom left). While it may be tempting to read this as negation or ’erasure’ in the sense described above, the trope of ’cutting’ an animal has significance in regional idioms, both contemporary and ancestral (see Skinner and Challis 2022 for other articulations), often relating to rainmaking practices. Further amendments include a circling of this symbol and the addition of a crude horse’s head (black lines, left). The introduction of the horse came at a significant inflexion point in the region (Challis 2008; see parallels in the Northern Cape in Skinner 2017) amidst a reordering of identity in response to colonial pressure and increasing admixture amongst regional populations.

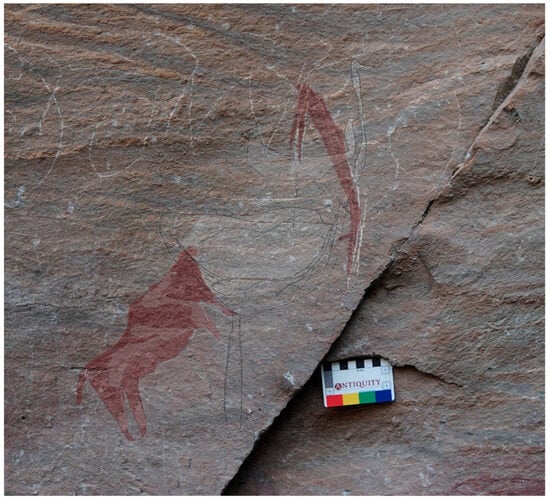

Figure 16.

Incised modification of painted substrate (bottom left), addition of horse and rider (bottom right) and ostriches (top left, top right), also with a rider and reins (top left).

The exercise here is interesting in part because of its overt reconfiguration of earlier motifs into ones that are more ’intelligible’ and/or relevant to the moment, incorporating a characteristic behaviour of earlier peoples (painting) into a practice with tighter temporal bounds. Moreso is the addition of ostriches (Struthio camelus). Ostriches are not endemic to this area (Stewart et al. 2020), and in some cases, the nearest populations would be on the order of hundreds of kilometres away. However, there is a documented approach of populations from the Northern Cape along the Senqu River (Stewart et al. 2016), a major water body that evidence suggests was a significant access and trade route, whose use appears to have some antiquity.

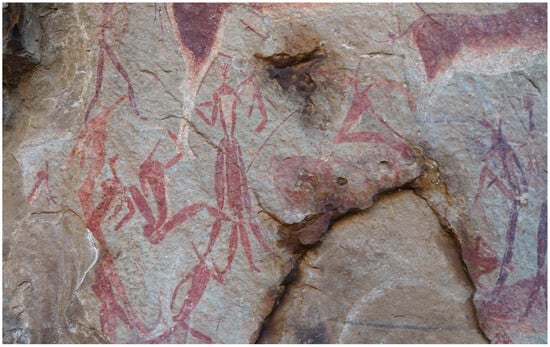

Drawing reference to ostriches has the partial effect of referencing those territories from which ostriches come. In |Xam ethnography, one of the predominant source domains for understanding rock art in the region, territorial origin is a significant constituent element of identity (Skinner and Challis 2022; Skinner 2023); to be from a place is to be part of what makes it what it is, and a place is reciprocally defined by those agents who inhabit it and through their activities define its character. To engage in painting or imagemaking signals certain models of identity in place, not least because certain places are defined by being the locales where images are typically made, but also drawing on the significance of the signs of presence left in an imagined longue duree, prior to one’s later contributions to the texture of the site. To bring in ostriches here is to bring in elements of identity from another place (the Northern Cape, in this case), and to render them in this way (in a mode reminiscent of engravings common to that region; see McGranaghan 2016; Skinner 2017) contextualises place and artist by this new indicator of presence. Secondary artists literally and figuratively positioned themselves within a common spatial context as primary ones by physically placing characteristic markers of their points of origin over and between (see Figure 17, below) markers of earlier populations. Their conduct reflected a cultural model of the conduct of those imagined predecessors in turn.

Figure 17.

Two incised/scratched ostriches placed between earlier human and animal forms, executed in red ochre. Khomo Patsoa, Highland Lesotho. Base image and overlay by author.

The process of conspicuous replication of the formative acts of a site continues on other panels (Figure 18), notably including painted interventions, which are typically less common than more expedient, engraved ones. Some of these are far more overt than is typical, as here, including actual replication of original elements (top right). Here, three elands have been reproduced in sequence, with a primary red ochre image (centre; itself significantly abraded) replicated in a secondary painted register (top; orange pigment; itself further amended with a second scratched overlay) and a more ephemeral incised one (lower middle). The orange pigment here is very similar to what has elsewhere (Challis and Sinclair Thomson 2022) been identified as a ’post-disconnect’ variety: chalky and vivid, but typically with minimal longevity and vulnerable to weathering. This reflects disruptions in the trade routes that had previously carried model pigment components across the subcontinent but which were disrupted during the colonial period, leading to a large number of more expedient pigment formulae, often with similar textures. This pigment has been used elsewhere in the site as well, and then to overtly replicate more highly weathered, red ochre motifs (as in Figure 19 below).

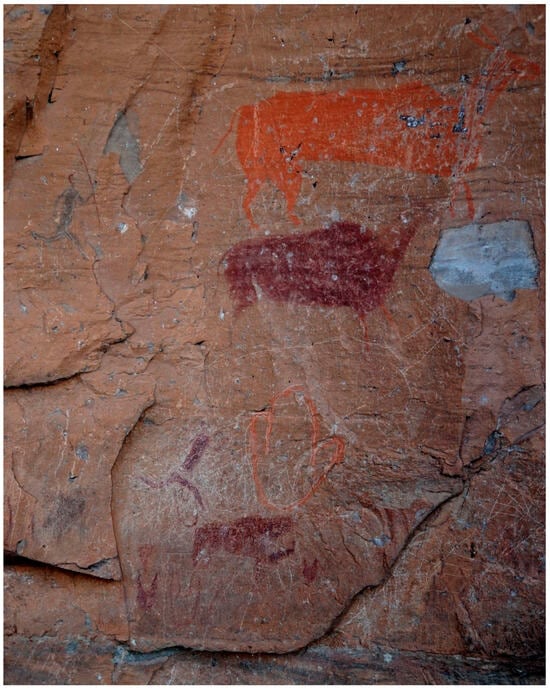

Figure 18.

Extensive modifications of a painted panel at Khomo Patsoa spread across several strata, including numerous painted and incised modifications.

Figure 19.

Conspicuous replication of a primary motif in a ’post-disconnect’ pigment. Khomo Patsoa, Highland Lesotho. Image courtesy Sam Challis.

One striking aspect of the site is a figure that has not been overlaid with secondary additions but rather almost highlighted by them (Figure 20). The figure has been surrounded with incisions and rubbing, and while these have likely affected the longevity of the primary image, care appears to have been taken not to strip the primary pigments. Secondary engagements achieved a certain degree of adornment-by-incision, the process of which involved a highly tactile, embodied connection to the practice of imagemaking at the site. This is then further elaborated by painted additions of aprons (attached to the human figure, and with four more below; red ochre). As with the above references to ostriches, this appears to imply a degree of negotiation of personal presence through literal placement amongst or between signs of the presence of other, likely past, peoples. Aprons are closely associated with Khoe identities and initiations in particular (see Hollmann 2014). Although ’San’ and ’Khoe’ identities have ambiguous contours in southern African history (see Morris 2022, pp. S115–16), it remains possible that some disambiguation could be underway here, invoking a characteristic element of distinct Khoe practice, again with reference to defining activities of prior populations, incorporating the signs of the presence of both into a distinctly new expression.

Figure 20.

Detail of extensive modification—variably somewhere between ’amendment’ and ’retouch by scarring’ in Brady et al.’s (2021) taxonomy, including painted superimpositions (aprons)—of the panel in Figure 18. Image courtesy Sam Challis.

The intent of this contribution is to be a primarily theoretical overview, as developing site-specific interpretations is challenging without space to develop site and regional history with sufficient resolution to offer specific interpretation, which is highly challenging within the scope of a single article. However, there is a suggestion of tantalising dialogue at play in these expressions; secondary contributions—signs of presence in themselves—literally and figuratively placed in the midst of the signs of the presence of others, (re)contextualising both in the process. The corresponding negotiation shows itself in the implicit appeal to common cultural ground through embodied replication, both of the practice and the associated images, and in the modification of earlier signs of presence to accord with new origins (ostriches from the Northern Cape) and identity expressions (aprons). There is perhaps also a degree of sense-making underway, as with the alteration of an image of fat-tailed sheep at the site (Figure 21). The site itself has been extensively modified to accommodate stonewalled enclosures, the floors of which are covered in caprine droppings (see Skinner and Challis 2024), although regional history is also one characterised by the influx of heterogeneous groupings variably taking up herding and raiding practices. The addition of an engraved enclosure (as above) has a certain perspective encoded in it—to the secondary artist’s eye, when sheep are kept, it is in an enclosure.

Figure 21.

Painted primary image of fat-tailed sheep (black pigment), amended with two horses (top) and what appears to be a holding enclosure with a small gate (bottom right), as incised modifications.

4. Identity Through Iteration: Audiences, Identities and Avenues for Interpretation

The case studies examined above reveal a complex pattern of engagement with inherited artistic traditions, where different communities positioned themselves through selective interpretation and modification of existing imagery. To understand these practices as expressions of identity, we must consider the spectrum of audiences involved—both those creating secondary images and those for whom they were intended. I have focused on ’interpretive engagements’; that is, those modifications which can be assessed to hold some symbolic content through selectivity of intervention and placement. In this respect, the secondary imagemaker is, in effect, an established audience of the primary art, albeit one working with their own particular lens on the imagery and the processes they imagined to have brought it about.

The time difference between primary and secondary art, artists, contexts and audiences is a challenge to interpretation, although at once, it is an inescapable property of secondary art. We have limited capacity to specify a particular moment in the art, and so must make do with stylistic, modal or subject matter changes. We have a similarly limited capacity to specify a particular moment in the audience, but that does not preclude identifying changes in them. Change over time is ever a thorny subject—here as in the rest of archaeological practice (see Crellin 2020). Sociocultural shifts are prone to unevenness and nonlinearity (cf. Wylie 2002, p. 52; Hamilakis 2016, pp. 679–80). We are nonetheless obliged to recognise them while also not rooting them so deeply that we essentialise the identities involved (discussion in Challis 2017; Skinner and Challis 2023).

The implication of San identity tends to bring with it ritual associations, but while these secondary modifications do not possess overt ritual indicators, some caution is due when assuming that this renders them products of completely inauthentic practices. While rock art is typically seen as originating in ritual contexts, there remains the reasonable allowance that “not all art was produced for ritual purposes or during ritual experiences” (Ross and Davidson 2006, p. 306). Even if it was, defining specific images as ritual in nature presents significant challenges.

Seemingly prosaic activities were attributed profound metaphysical dimensions in San ethnographies (Guenther 2020, p. 258), while numinous occurrences routinely demonstrated their relevance to the course of daily life (McGranaghan 2012, p. 202; see also McGranaghan and Challis 2016; Challis and Skinner 2021). Neurological processes could centre ‘real’ experiences even in overtly altered states of consciousness, and then with particular veracity (Skinner and Challis 2023), further blurring ontological boundaries. The absence of diagnostic ritual features thus proves a poor criterion for classification—indeed, there would be a certain irony in ’ritual’, the proverbial catch-all for anomalous behaviours or artefacts (Insoll 2004, pp. 1–2, 11–12; see also Goldhahn et al. 2020, pp. 61–62; Gunn et al. 2022, p. 21), acting as an exclusionary criterion for a practice with such markedly ambiguous parameters.

Instead, the use of art-as-substrate by secondary artists reveals an overtly socialised process of identity formation. These artists consistently chose to place their images over or adjacent to existing ones, concentrating on nodes of existing expression. Their placement does not stem from limitations on available rock surfaces (Gunn et al. 2022, p. 2), suggesting instead that the imagistic substrate was chosen as ‘material’ for which specific social and metaphorical qualities were desired. This selective engagement complicates traditional archaeological approaches to authenticity and cultural continuity: even if changes in ‘style’ or subject matter implied different authorship, the secondary artist made deliberate choices about which primary images to engage with and how in the service of specific goals which may have included conscious expression of difference.

‘Style’ presents particular challenges in this context. While already contentious in rock art research for its tendency to impose researcher perspectives over emic categories (Whitley 2001, p. 24; cf. Mallen 2008; Laue 2021), this challenge is compounded in secondary imagemaking. Maloti–Drakensberg corpora demonstrate significant diversity in execution even within recognisably ‘traditional’ imagery—from fine-lined polychromatic paintings to monochrome figures, from naturalistic to schematic forms. When dealing with secondary modifications that deliberately transform or reinterpret these forms, the very features that might signal ‘authenticity’ in primary images—such as fine brushwork or shading—may be intentionally altered or simplified in secondary engagements, not exclusively from lack of ability but as deliberate choices that carried their own semantic weight. This is not to suggest that technical limitations played no role—indeed, the availability of materials and technologies undoubtedly shaped secondary expressions—but rather that within these constraints, the choices made in relation to existing imagery reflect attitudes and relationships to inherited traditions that transcend mere technical expediency.

A more productive approach to understanding identity through iteration focuses on the physical relationships between images rather than presumed cultural or temporal divisions (after Navratilova 2023, pp. 324–25). While secondary images typically post-date primary ones, the temporal gap can range from immediate responses (Goldhahn et al. 2020, pp. 75–76) to engagements spanning centuries or millennia (Brady et al. 2021, p. 7). Direct superimposition allows us to establish relative chronology (Pearce 2010), but even this tells us little about the cultural distance between artists. A single site might contain near-contemporary modifications by culturally distinct groups alongside temporally distant engagements by communities that maintain strong cultural continuity with primary artists. The physical relationship between images thus becomes our primary evidence for understanding how secondary artists positioned themselves relative to earlier traditions.

The decision to overlay or engage with a primary image, regardless of the degree of cultural continuity, cites or invokes it within a new context. Secondary artists demonstrate a sensitivity to models of the past represented by primary images, relying on something between “cultural memory” and “aesthetic consumption” (Navratilova 2020, pp. 7–8) as the basis for their own images. Primary images thus become more than passive substrates; they form an “interactive… symbolic matrix” (Motta et al. 2020, p. 147) into which secondary artists place themselves and their contributions. This process is fundamentally intertextual (Ragazzoli et al. 2018, p. 10); it is one text being read and rewritten simultaneously as another.

4.1. Audiences and Identity Formation

Following Navratilova (2020, pp. 103–4), we could broadly divide audiences into emic and etic, placing them within or without a common cultural perspective. However, this is a graduated rather than a binary assessment. The latter-day history of imagemaking in the Maloti–Drakensberg reveals a complex landscape of cultural formation. These communities underwent significant social, cultural, and genetic admixture at fluctuating magnitudes across the last two millennia, creating hybridised societies with diverse origins, nonetheless tracing much of their identities and practices back to Maloti San hunter-gatherers (e.g., Challis 2012, 2014, 2016; see Daniels et al. 2023). Their choice to perpetuate a practice—and then, more specifically, to use or reference particular symbols and logics—indicates a conspicuous invocation of this part of their composite identities. These communities underwent significant social, cultural and genetic admixture, retaining a variable measure of earlier idioms (some of which persist into the present; see Skinner 2022), and thus, the exact degree to which they constituted either emic or etic audiences would vary accordingly.

Navratilova (2020, pp. 103–5) makes a further useful distinction within the emic audience: systemic and nonsystemic. The systemic audience comprehends the intent and origins of a primary image and structures their responses within a common framework. However, it is possible for the emic range to represent “different audiences with related, but not identical agendas” (Navratilova 2020, p. 109). A secondary artist or audience could approach an image already hundreds or thousands of years old while possessing sufficient common culture to involve themselves as an emic audience, but in their choice to consequentially amend, alter or erase it for a novel purpose, they might engage the image as a nonsystemic actor.

Images from earlier times and peoples play a role as markers of significance and records of earlier social precedents (Skinner and Challis 2022; Skinner 2023), making rock art sites culturally meaningful to audiences across the range of emic to etic, whether they interpret the original meanings or not. This opens sites to a corresponding range of systemic and nonsystemic engagements. Just as with the selection of materials for other cultural practices, the choice of which images to engage with, and how to engage with them, carries significant metaphorical weight. Secondary artists were not simply selecting neutral surfaces but rather choosing specific artistic expressions that embodied what they perceived of their own histories and relationships to place.

4.2. Relational Identity and Non-Human Agency

The character of identity in the ethnographic source contexts for southern African rock art interpretation (see King 2015, p. 411) is one that positions interpersonal and interspecies negotiation as a core metaphysical process. This was because identity was not a fixed quality but rather a malleable, negotiated property of one’s relationships with others, human or otherwise (McGranaghan and Challis 2016; see, e.g., Green 2023). To be human is to occupy the range of habits, territories and physiologies that define humans in relation to other kinds of persons, who, in turn, do the same relative to their own identities (Skinner and Challis 2022).

Occupation of this range occurs through the accumulation of historical associations (cf. Ouzman 1996), literal position within certain habitats, and practical relationships with specific places and their inhabitants (Challis and Skinner 2021; Skinner 2022). The behaviours of humans and non-humans were viewed as products of pre-existing social precedents (Skinner and Challis 2022; Skinner 2023), intimately tied to differentials of identity and the convergences of historical relationships.

If non-human entities could be conceived as having cultural agency, then the act of artistic engagement becomes not just a human practice but a broader mechanism of relational meaning-making. It points to histories that are not only anthropocentric in origin or intended audience but also have a particular role in more universal strategies of ecological communication. In art, patterns of presence on the landscape—ranging from household scatters and surface archaeology to spoor, scent, and physical appearance—are delimited from the shapes of bodies, abstracted into more expressive forms, while yet retaining their role as records of one’s place amongst others (Skinner 2023).

In this context, art serves as a significant format for signalling connections and associations, just as humans and non-humans have always done. Through recontextualisation, secondary artists managed or expressed their relationships relative to others, drawing from a common precedent accessible to more than just themselves. The value of this practice is not diminished if secondary artists or audiences did not share the intentions or framing of primary ones; they demonstrate how primary images “were read by subsequent generations who, by engaging with the art, kept the images alive” (Gunn et al. 2022, p. 21), with or without direct cultural continuity. These engagements reflect various groups “(re)connect[ing] not only with past populations, but with the inherited landscape, where artists, instead of being passive consumers or readers” played an active part in the texturing of place and identity (Motta 2019, p. 492).

4.3. Secondary Imagemaking as Identity Work

This selective engagement reveals secondary imagemaking as a sophisticated form of identity work. If the subject of analysis is exclusively that of emic, systemic societies, then secondary images will have limited reference. If the subject is art and artistic practices, we can recognise value even amongst etic, nonsystemic audiences. The complexity of these audience interactions is perhaps best illustrated by the remarkable site of Thaba Sione, where human and non-human actors engaged in mutually intelligible imagemaking, with human actors making secondary modifications to rock surfaces originally marked by rhinoceroses (Ouzman 1996).

Although typically not conceived of as ’secondary imagemaking’ in the sense described here, it demonstrates the usefulness of taking a more comprehensive, inclusive view of cognate practices. The humans making art at Thaba Sione would themselves have been some variation of emic/etic, (non)systemic audience, just as we researchers are yet another such etic, nonsystemic audience making our respective interpretations based on the elements of context and form that are accessible to us.

Each of these audiences “came with their own preconceptions and had to develop specific skills to be able to proceed with their task of recording and ultimately mediating the ancient records to new generations” (Navratilova 2020, p. 111; also Pawlikowska-Gwiazda 2021, p. 142). By integrating primary images, secondary images translate the underlying strata, comment upon them, and produce an account of both which is simultaneously derivative and novel, ’authentic’ in its way yet possibly nonsystemic, and altogether, an iterative account whose entries are each rich with the past’s own view of itself.

The case examples presented earlier illustrate this process of identity construction through iteration. In the first examples, annotations and ephemeral changes contributed to the texturing of the sites without permanently changing them, acknowledging the significance of the original while adding expedient interpretive layers, using the tools that were ’close to hand’. In the second set, more pronounced modifications suggest a more assertive transformation of meaning, potentially reflecting communities in transition, negotiating their relationships to past traditions, likely as part of negotiating their then-present status on the same landscape. In each case, successive communities positioned themselves in relation to imagined past peoples through the reuse of their signs of presence as symbolic resources, creating palimpsests which reflected their attitudes and perceived relations to the places they marked, inserting themselves into the course of history in the process. Their technical choices—whether ephemeral charcoal or permanent engraving, peripheral enhancement or more transformative modification—encoded specific attitudes towards these inherited traditions and reveal how different communities positioned themselves within changing cultural landscapes.

5. Conclusions

The analysis presented in this paper demonstrates how secondary imagemaking practices in southern Africa served to articulate and negotiate identity through iterative engagement with earlier artistic traditions. The technical choices that followed, from careful enhancement to complete transformation, further encoded specific attitudes towards these inherited traditions, although, in the process, indicating the aspects of the compositions of secondary artists themselves. While the depth of engagement undoubtedly varied across individuals and contexts, patterns of selectivity in these modifications suggest that secondary artists were not merely casual participants but were, to varying degrees, engaged in positioning themselves within existing narratives and signatures of presence which defined the places they marked. The iterative process of modifying and reinterpreting the figured substrates suggests something about the character and semantic content of the practice itself, that there was something in an overtly socialised material that made it ’fit for use’ when developing new articulations of self and imaginations of the past, regardless of whether such articulations were fully conscious or partly intuitive expressions of cultural position, history and genealogy.

The case studies examined here reveal distinct approaches to these dialogues, ranging from relatively ephemeral and, in some ways, reifying engagement with existing images to permanent and invasive alterations of substrate and recontextualisation of original forms. In some ways, their technical choices also reflected their own understandings of personal heritage and composition; their relative coherence with or contrast to the earlier peoples, as implied in the primary images, shows in their more or less significant ’reworking’ of prior signs of presence. They iterated upon the images to reflect their own iterative, composite histories.

The framework of iteration thus provides a valuable approach for understanding these practices, encouraging care when using terminologies like ’graffiti’ or ’vandalism’, amongst others, which may obscure their cultural significance. Selective interpretive engagement reflects a degree of intentionality and semantic content to these activities, which can be read for its own historical implications.

This perspective has broader implications for understanding how African identities have been articulated and preserved through engagement with cultural landscapes. Rather than seeing modification as degradation, we can recognise these practices as sophisticated and perhaps unusually self-aware forms of identity work. Secondary artists were but one of many audiences engaging with these artistic traditions—a spectrum that includes contemporary researchers ourselves—each bringing our respective measures of subjectivity to bear on the object of our common interest. Each layer of modification thus represents not just artistic engagement but a specific community’s interpretation and commentary, creating what amounts to material epistolaries—communications between different moments in time encoded in the archaeological record itself.

This study of secondary imagemaking thus offers valuable insights into both past practices of identity expression and the effects of our own analytical approaches. It reminds us that the interpretation of cultural heritage is not solely the domain of ourselves. As emerging approaches in archaeological research demonstrate, studying these complex engagements will require an evolution in our tools just as much as our theories. This includes everything from photogrammetry and image enhancements used for precise digital documentation (Magnani et al. 2020) to microtopographical analysis revealing subtle surface modifications (Jalandoni and Kottermair 2017), from improvements in chronometric dating providing ever more specific temporal context (Bonneau et al. 2017) to non-invasive analysis offering ever more detailed material insights (Mauran et al. 2019). Yet, at the core of this challenge lies the issue of detection and recognition. Secondary images remain sparsely covered in the extant literature precisely because they are often hidden from view, omitted from the record through interpretive misalignment and, sometimes, misplaced value judgements. The real onus is on research to locate these expressions anew, recognising that these insider accounts of African history are written into the land itself.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Appadurai, Arjun, ed. 1986. The Social Life of Things. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Battiss, Walter. 1939. The Amazing Bushmen. Blockley: Red Fawn. [Google Scholar]

- Blundell, Geoffrey. 2004. Nqabayo’s Nomansland: San Rock Art and the Somatic Past. Uppsala: Uppsala University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bodel, John. 2001. Epigraph and the ancient historian. In Epigraphic Evidence. Edited by John Bodel. London: Routledge, pp. 1–56. [Google Scholar]

- Bolton, Lissant. 2003. The object in view. In Museums and Source Communities. Edited by Laura Peers and Alison K. Brown. London: Routledge, pp. 42–54. [Google Scholar]

- Bonneau, Adelphine, David Pearce, Peter Mitchell, Richard Staff, Charles Arthur, Lara Mallen, Fiona Brock, and Tom Higham. 2017. The earliest directly dated rock paintings from southern Africa: New AMS radiocarbon dates. Antiquity 91: 322–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, Liam M., Robert G. Gunn, and Joakim Goldhahn. 2021. Rock art modification and its ritualized and relational contexts. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology of Indigenous Australia and New Guinea. Edited by Ian J. McNiven and Bruno David. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Challis, Sam. 2008. The impact of the horse on the AmaTola ‘Bushmen’: New identity in the Maloti-Drakensberg Mountains of southern Africa. Ph.D. thesis, Oxford University, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Challis, Sam. 2012. Creolisation on the nineteenth-century frontiers of southern Africa: A case study of the AmaTola ’Bushmen’ in the Maloti-Drakensberg. Journal of Southern African Studies 38: 265–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challis, Sam. 2014. Binding beliefs: The creolisation process in a ’Bushman’ raider group in nineteenth century southern Africa. In The Courage of ||Kabbo: Celebrating the 100th Anniversary of the Publication of Specimens of Bushman Folklore. Edited by Janette Deacon and Pippa Skotnes. Sunnyside: Jacana, pp. 246–64. [Google Scholar]

- Challis, Sam. 2016. Re-tribe and resist: The ethnogenesis of a creolised raiding band in response to colonisation. In Tribing and Untribing the Archive. Edited by Carolyn Hamilton and Nessa Leibhammer. Pietermaritzburg: University of KwaZulu-Natal Press, pp. 282–99. [Google Scholar]

- Challis, Sam. 2017. Creolization in the investigation of rock art of the colonial era. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. Edited by Bruno David and Ian J. McNiven. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Challis, Sam. 2018. Collections, Collecting and Collectives: Gathering Heritage Data with Communities in the Mountains of Matatiele and Lesotho, Southern Africa. African Archaeological Review 352: 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challis, Sam. 2022. History debunked: Endeavours in rewriting the San past from the Indigenous rock art archive. In Powerful Pictures: Rock Art Research Histories Around the World. Edited by Jamie Hampson, Sam Challis and Joakim Goldhahn. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 89–104. [Google Scholar]

- Challis, Sam, and Andrew Skinner. 2021. Art and influence, presence and navigation in southern african forager landscapes. Religions 12: 1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Challis, Sam, and Brent Sinclair Thomson. 2022. The Impact of Contact and Colonization on Indigenous Worldviews, Rock Art, and the History of Southern Africa: ‘The Disconnect’. Current Anthropology 63: S91–S127. [Google Scholar]

- Crellin, Rachel J. 2020. Change and Archaeology. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Daniels, Ryan Joseph, Maria Eugenia D’Amato, Mpasi Lesaoana, Mohaimin Kasu, Karen Ehlers, Paballo Abel Chauke, Puseletso Lecheko, Sam Challis, Kirk Rockett, Francesco Montinaro, and et al. 2023. Genetic heritage of the Baphuthi highlights an over-ethnicized notion of “Bushman” in the Maloti-Drakensberg, southern Africa. The American Journal of Human Genetics 110: 880–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawdy, Shannon Lee. 2016. Patina: A Profane Archaeology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Delannoy, Jean-Jacques, Bruno David, Robert G. Gunn, Jean-Michel Geneste, and Stéphane Jaillet. 2018. Archaeomorphological mapping: Rock art and the architecture of place. In The Oxford Handbook of the Archaeology and Anthropology of Rock Art. Edited by Bruno David and Ian J. McNiven. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Deleuze, Gilles, and Felix Guattari. 1987. A Thousand Plateaus: Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. [Google Scholar]

- Dowson, Thomas A. 2009. Re-animating Hunter-gatherer Rock-art Research. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 19: 378–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dronfield, Jeremy. 1996. Entering alternative realities: Cognition, art and architecture in Irish passage tombs. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 61: 37–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Elizabeth, Chris Gosden, and Ruth Phillips, eds. 2006. Sensible Objects: Colonialism, Museums and Material Culture. Bavaria: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Forssman, Tim, and Christian Louw. 2016. Leaving a Mark: South African war-period (1899–1902) refuge graffiti at Telperion shelter in Western Mpumalanga, South Africa. South African Archaeological Bulletin 71: 4–13. [Google Scholar]

- Goldhahn, Joakim, Sally K. May, Josie Gumbuwa Maralngurra, and Jeffrey Lee. 2020. Children and rock art: A case study from western Arnhem Land, Australia. Norwegian Archaeological Review 53: 59–82. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Dawn. 2023. Exploring personhood and identity marking: Paintings of lions and felines in San rock art sites from the southern Maloti-Drakensberg and northeastern Stormberg, South Africa. Azania 58: 434–76. [Google Scholar]

- Guenther, Mathias. 2020. Human-Animal Relationships in San and Hunter-Gatherer Cosmology, Volume I: Therianthropes and Transformation. Berlin and Heidelberg: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, Robert G. 2019. Degrees of change: Amendment and alteration in Australian Aboriginal rock art. In Aesthetics, Applications, Artistry and Anarchy: Essays in Prehistoric and Contemporary Art. Edited by Jillian Huntley and Nash George. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 87–97. [Google Scholar]

- Gunn, Robert G., Bruno David, Jean-Jacques Delannoy, Benjamin Smith, Augustine Unghangho, Ian Waina, Balanggarra Aboriginal Balanggarra Aboriginal Corporation, Leigh Douglas, Cecilia Myers, Pauline Heaney, and et al. 2022. Superpositions and superimpositions in rock art studies: Reading the rock face at Pundawar Manbur, Kimberley, northwest Australia. Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 67: 101442. [Google Scholar]

- Hamilakis, Yannis. 2011. Archaeological ethnography: A multitemporal meeting ground for archaeology and anthropology. Annual Review of Anthropology 40: 399–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilakis, Yannis. 2016. Decolonial archaeologies: From ethnoarchaeology to archaeological ethnography. World Archaeology 48: 678–82. [Google Scholar]

- Hampson, Jamie. 2015. Presenting rock art and perceiving identity in South Africa and beyond. Time and Mind 8: 373–391. [Google Scholar]

- Harmanşah, Ömür. 2017. Graffiti or monument? Inscription of place at Anatolian rock reliefs. In Scribbling Through History Graffiti, Places and People from Antiquity to Modernity. Edited by Chloe Ragazzoli, Omur Harmanşah, Chiara Salvador and Elizabeth Frood. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Hollmann, Jeremy C. 2007. The ’cutting edge’ of rock art: Motifs and other markings on Driekuil Hill, North West Province, South Africa. Southern African Humanities 19: 123–51. [Google Scholar]

- Hollmann, Jeremy C. 2014. ‘Geometric’ motifs in Khoe-San rock art: Depictions of designs, decorations and ornaments in the Gestoptefontein-Driekuil Complex, South Africa. Journal of African Archaeology 12: 25–42. [Google Scholar]

- Ingold, Tim. 2013. Making: Anthropology, Archaeology, Art and Architecture. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Insoll, Timothy. 2004. Archaeology, Ritual, Religion. London: Psychology Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jalandoni, Andrea, and Maria Kottermair. 2017. Rock art as microtopography. Geoarchaeology 33: 579–93. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Andrew. 2007. Memory and Material Culture. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Tristen, and Sally K. May. 2015. Rock art and ritual function. The Artefact 38: 53–66. [Google Scholar]

- King, Rachel. 2015. ‘A loyal liking for fair play’: Joseph Millerd Orpen and knowledge production in the Cape Colony. South African Historical Journal 67: 410–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, Rachel. 2024. An archaeology of interruption: Expulsion and hiatus in Southern Africa’s long past. History and Anthropology 35: 1053–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopytoff, Igor. 1986. The cultural biography of things: Commoditization as process. In The Social Life of Things. Edited by Arjun Appadurai. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 64–91. [Google Scholar]

- Langley, Michelle C., and Mirani Litster. 2018. Is It Ritual? Or Is It Children? Distinguishing Consequences of Play from Ritual Actions in the Prehistoric Archaeological Record. Current Anthropology 59: 616–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laue, Ghilraen. 2021. Rock art, regionality and ethnography: Variation in southern African rock art. Rock Art Research 32: 138–51. [Google Scholar]

- Laue, Ghilraen, and Claire Dean. 2022. Rock art conservation with a focus on Southern Africa. In Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Anthropology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David. 1980. Ethnography and Iconography: Aspects of Southern San Thought and Art. Man 15: 467–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David. 1984. The Empiricist Impasse in Southern African Rock Art Studies. The South African Archaeological Bulletin 39: 58–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David. 1998. Quanto?: The Issue of “Many Meanings” in Southern African San Rock Art Research. South African Archaeological Bulletin 53: 86. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David, and Jean Clottes. 1998. The Mind in the Cave the Cave in the Mind: Altered Consciousness in the Upper Paleolithic. Anthropology of Consciousness 9: 13–21. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David, and Thomas A. Dowson. 1988. The Signs of All Times: Entoptic Phenomena in Upper Palaeolithic Art. Current Anthropology 29: 201–45. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis-Williams, J. David, and Thomas A. Dowson. 1990. Through the veil: San rock paintings and the rock face. South African Archaeological Bulletin 45: 5. [Google Scholar]

- Magnani, Matthew, Matthew Douglass, Whittaker Schroder, Jonathan Reeves, and David R. Braun. 2020. The Digital Revolution to Come: Photogrammetry in Archaeological Practice. American Antiquity 85: 737–60. [Google Scholar]

- Malafouris, Lambros. 2013. How Things Shape the Mind: A Theory of Material Engagement. Cambridge: MIT Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mallen, Lara. 2008. Rock Art and Identity in the North Eastern Cape Province. Master’s thesis, University of the Witwatersrand, Johannesburg, South Africa. [Google Scholar]

- Mauran, Guilhem, Matthieu Lebon, Florent Détroit, Benoît Caron, Alma Nankela, David Pleurdeau, and Jean-Jacques Bahain. 2019. First in situ pXRF analyses of rock paintings in Erongo, Namibia: Results, current limits, and prospects. Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences 11: 4123–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranaghan, Mark. 2012. Foragers on the Frontiers: The |Xam Bushmen of the Northern Cape, South Africa, in the Nineteenth Century. Ph.D. Thesis, Oxford University, Oxford, UK. [Google Scholar]

- McGranaghan, Mark. 2016. The Death of the Agama Lizard: The Historical Significances of a Multi-Authored Rock Art Site in the Northern Cape (South Africa). Cambridge Archaeological Journal 26: 157–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranaghan, Mark, and Sam Challis. 2016. Reconfiguring Hunting Magic: Southern Bushman (San) Perspectives on Taming and Their Implications for Understanding Rock Art. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 26: 579–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGranaghan, Mark, Sam Challis, and David Lewis-Williams. 2013. Joseph Millerd Orpen’s ’A Glimpse into the Mythology of the Maluti Bushmen’: A contextual introduction and republished text. Southern African Humanities 25: 137–66. [Google Scholar]

- Merrill, Samuel Oliver Crichton. 2011. Graffiti at Heritage Places: Vandalism as Cultural Significance or Conservation Sacrilege? Time and Mind 4: 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Daniel. 2005. Materiality: An Introduction. In Materiality. Edited by Daniel Miller. Durham: Duke University Press, pp. 1–50. [Google Scholar]

- Mol, Lisa, Miguel Gomez-Heras, Charlotte Brassey, Owen Green, and Thomas Blenkinsop. 2017. The benefit of a tough skin: Bullet holes, weathering and the preservation of heritage. Royal Society Open Science 4: 160335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, David. 2022. River, Rock and ‘The Rain’s Magic Power’: Rock Art and Memory in the Northern Cape, South Africa. In Rock Art and Memory in the Transmission of Cultural Knowledge. Edited by Leslie Zubieta. Cham: Springer Nature, pp. 245–268. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, Ana Paula. 2019. From Top Down Under: New Insights into the Social Significance of Superimpositions in the Rock Art of Northern Kimberley, Australia. Cambridge Archaeological Journal 29: 479–95. [Google Scholar]

- Motta, Ana Paula, Martin Porr, and Peter Veth. 2020. Recursivity in Kimberley Rock Art Production, Western Australia. In Places of Memory: Spatialised Practices of Remembrance from Prehistory to Today. Edited by Christian Horn, Gustav Wollentz, Gianpiero Di Maida and Annette Haug. Oxford: Archaeopress, pp. 137–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mulvaney, Ken. 2009. Dating the Dreaming: Extinct fauna in the petroglyphs of the Pilbara region, Western Australia. Archaeology in Oceania 44: 40–48. [Google Scholar]