The Role of CT-Angiography in the Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Pictorial Essay of Active and Obscure Findings

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Definition and Incidence

1.2. Clinical Presentation

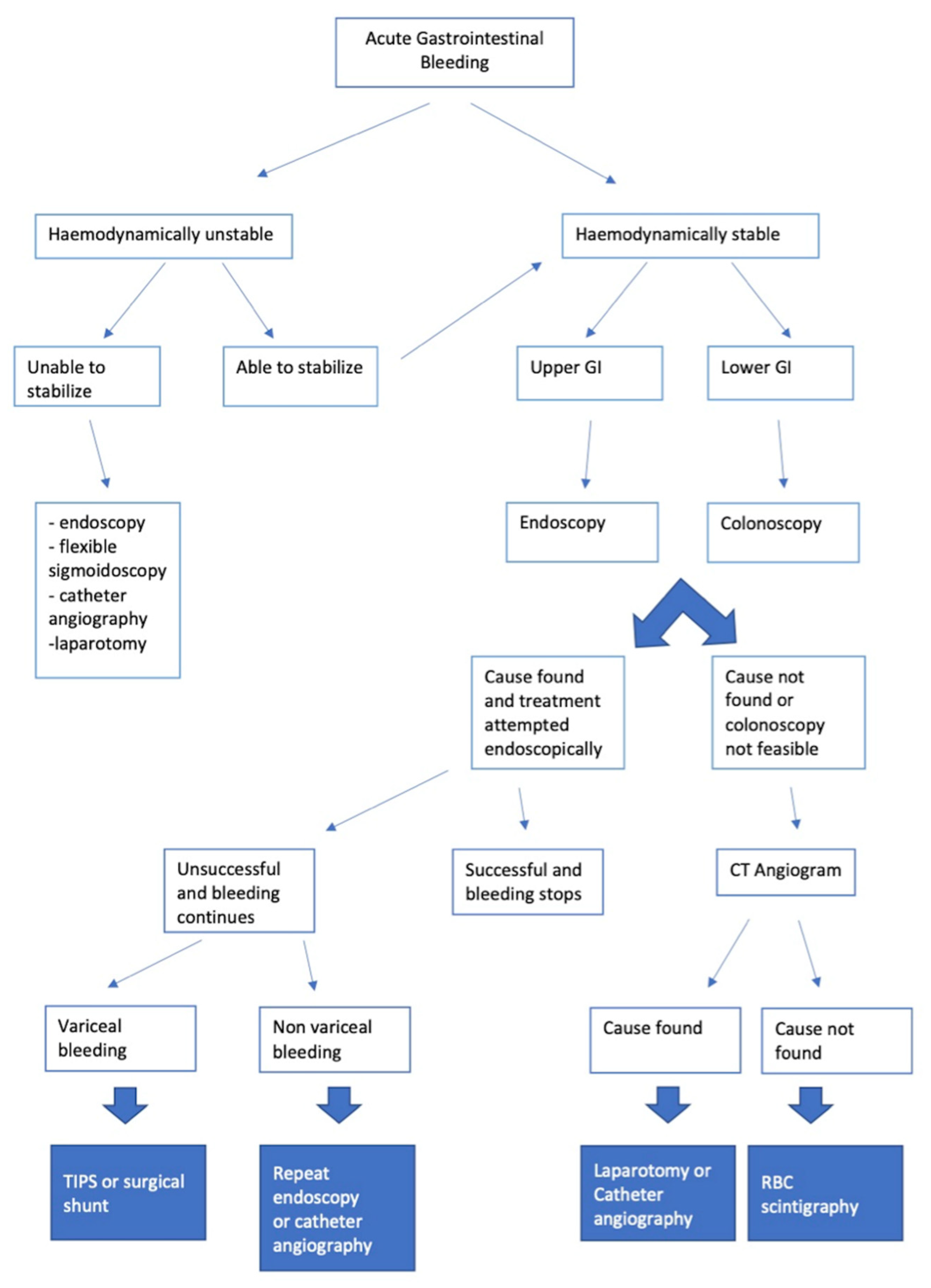

1.3. Diagnostic Pathway

1.4. Diagnostic Endoscopic and Imaging Techniques

2. The Diagnostic Role of CTA

2.1. CTA: Appropriateness Criteria

2.2. Examination Technique

2.3. Post-Processing

2.4. Dual-Energy CTA (DECTA)

2.5. Semiotics of Bleeding and Diagnostic Pitfalls of CTA

3. Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding (UGIB)

| UGIB DUE TO VARICES | ||

| Clinical Presentation | CT Findings | |

| Oesophageal-gastric varices due to portal hypertension (Figure 21) | Asymptomatic until they rupture in the oesophageal lumen and cause haematemesis or melaena or haematochezia depending on the severity of the bleeding. | Tortuous, enlarged, smooth tubular structures protruding into the oesophageal lumen or adjacent to the internal oesophageal mucosa. |

| NON-VARICEAL NON-VASCULAR CAUSES OF UGIB | ||

| Clinical Presentation | CT Findings | |

| Mallory–Weiss Tear (Figure 22) | A history of recent retching or haematemesis or “coffee grounds” emesis following violent vomiting, often after excessive alcohol consumption, and manifested by stabbing pain in the epigastrium and left side of the chest, radiating to the back. | Finding haemorrhagic spots or foci of extraluminal gas at the site of the mucosal laceration. |

| Oesophagitis (Figure 23) | Anaemia, retrosternal pain. | Diffuse oesophageal thickening, submucosal oedema and mucosal hyperaemia. |

| Oesophageal ulcer | Haematemesis, epigastric pain and odynophagia. | Thickening of the wall, peri-oesophageal gas and fluid collection, extraluminal contrast extravasation. |

| Oesophageal diverticulum (Figure 24) | Asymptomatic bleeding. | Haemorrhage in a focal herniation of the mucosa through a site of weakness in the muscle layer. |

| Peptic ulcer (Figure 25) | Manifestations range from asymptomatic to melaena or haematemesis, to hypovolaemic shock. Bleeding due to gastric ulcers often presents with haematemesis, while duodenal bleeding can present with tarry stools or even occasionally haematochezia, depending on the extent of bleeding. | Direct identification of active haemorrhage as extravasation of an intra-luminal “jet” or “blush” of contrast medium at the site of the haemorrhage, detected in the gastric fundus or duodenal lumen. |

| Neoplasia | Anaemia in a patient with a history of cancer. | A focal area of high attenuation within the bowel lumen that represents a bleeding point at the tumour site. |

| Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumour (GIST) (Figure 26) | Asymptomatic or bleeding. | Soft tissue density mass with variable areas of necrosis. They are usually highly vascularised and the enhancement of the lesion may vary from homogeneous to peripheral and irregular depending on the lesion dimension and grade of malignancy. |

| NON-VARICEAL VASCULAR CAUSES OF UGIB | ||

| Clinical Presentation | CT Findings | |

| Dieulafoy Lesion (Figure 27) | Melaena, haematemesis, haematochezia, or a combination of more than one of these signs, depending on the location of the lesion. | Abnormally enlarged submucosal vessel, which may appear tortuous, linear or as a non-specific “blush” of contrast medium at the mucosal/submucosal level. |

| Artero-Venous Malformations | Asymptomatic. | A tiny nidus of vascular potentiation appreciable in the arterial phase and often undetectable in the late phase. When associated with an early draining vein in the arterial phase, the lesion represents an AVM. |

| Aorto-Gastric Fistula (Figure 28) | Copious bleeding. | A connection between the aorta and the gastric lumen. Absence of adipose cleavage planes. |

| [23,24,25] | ||

4. Middle Gastrointestinal Bleeding/Small Bowel Bleeding (MGIB/SBB)

| NON-VASCULAR CAUSES | ||

| Clinical Presentation | CT Findings | |

| Tumour (Figure 29) | Asymptomatic or bleeding. | Irregular wall thickening with foci of active bleeding. |

| GIST | Asymptomatic or bleeding. | Soft tissue density mass with variable areas of necrosis. They are usually highly vascularised and the enhancement of the lesion may vary from homogeneous to peripheral and irregular depending on the lesion dimension and grade of malignancy. |

| Ulcer | Obscure bleeding. | Thickening of the walls and fluid collections, extravasation of contrast medium. CT is poorly sensitive in the detection of superficial lesions. |

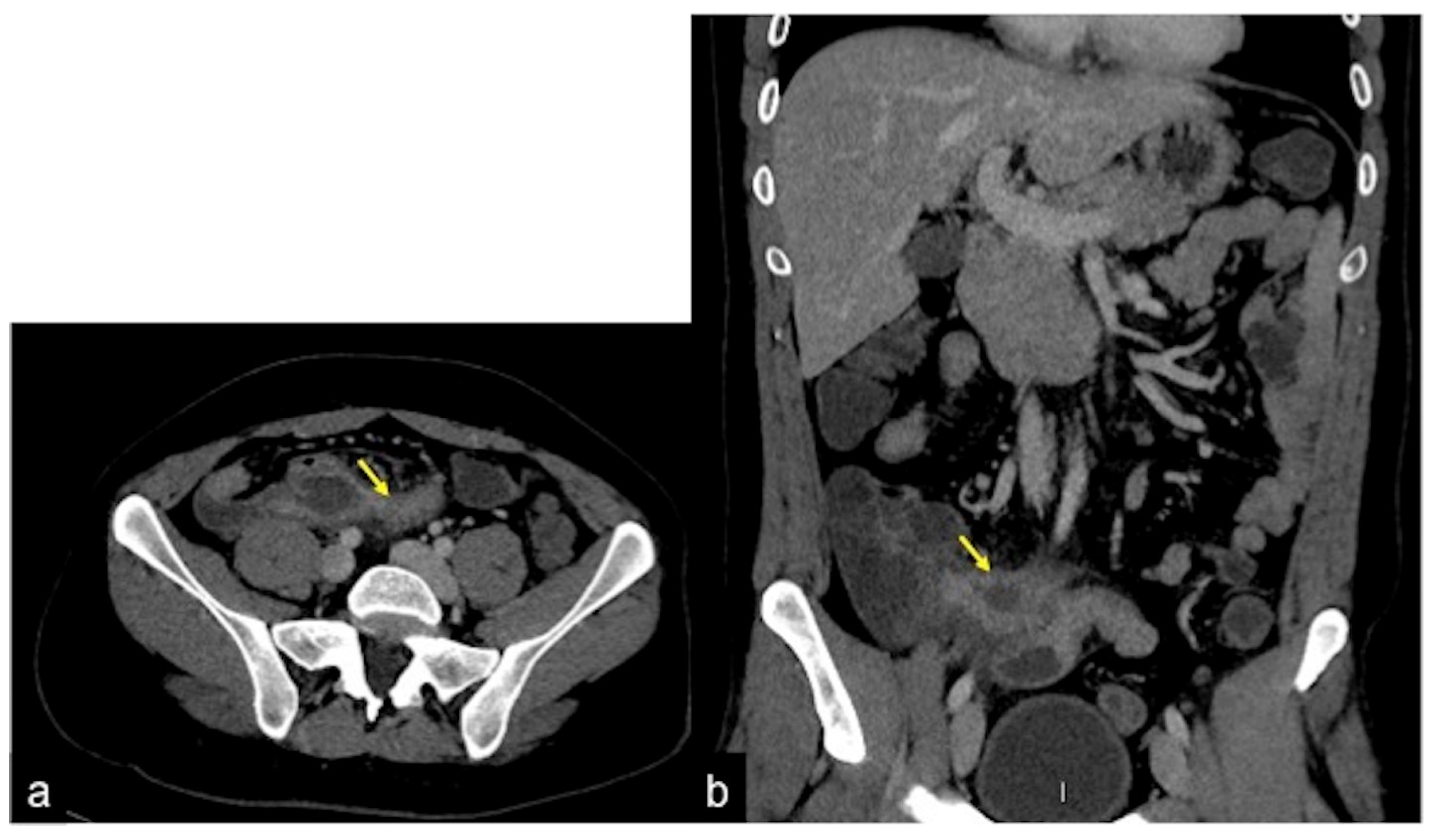

| Meckel’s Diverticulum (Figure 30) | Asymptomatic or, rarely, massive gastrointestinal bleeding. | A diverticulum with fluid or air content originating from the antimesenteric side of the distal ileum. |

| Jejunal-Ileal Diverticulum | Asymptomatic or, rarely, massive gastrointestinal bleeding. | Similar to Meckel’s diverticulum. |

| Aorto-Enteric Fistula (Figure 31) | Bleeding in a patient with a history of surgery for aortic aneurysm. | A connection between the aorta and the intestinal lumen. Absence of adipose cleavage planes. |

| Haemobilia (Figure 32) | Melaena, haematemesis, biliary colic, jaundice, or massive bleeding in a patient with a history of blunt or iatrogenic abdominal trauma. | Presence of blood in the gallbladder and biliary tree. |

| Pancreatic Haemorrhage | Intermittent epigastric pain in the abdomen, gastrointestinal bleeding (melaena, haematemesis, haematochezia) and raised serum amylase. | Pseudoaneurysm or pseudocyst with signs of active bleeding, associated with the finding of hyperdense material in the pancreatic ducts. |

| VASCULAR CAUSES | ||

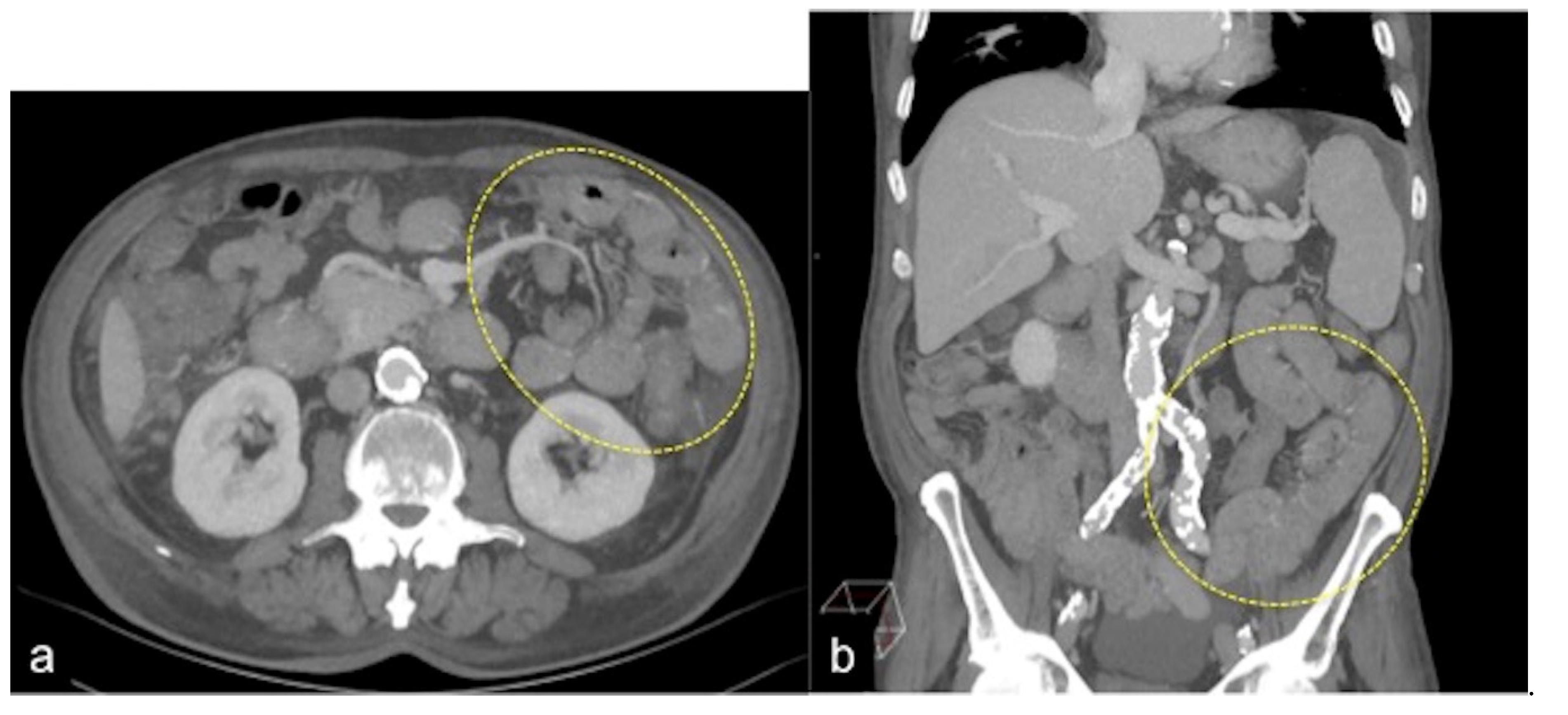

| Angiodysplasia (Figure 11) | Obscure bleeding. | Abnormally dilated, tortuous, thin-walled vessels involving small capillaries, veins and arteries. |

| Telangiectasia (Figure 18) | Iron deficiency anaemia with recurrent gastrointestinal bleeding. | Punctate area of enhancement with direct connections between arteries and veins. |

| Dieulafoy’s Lesion | Obscure bleeding. | Abnormal arteries typically protruding through a small mucosal defect ranging in size from 2 to 5 mm. |

| Venous Lesion | Obscure bleeding. | Varices may be visible in the enteric phase and become more intense in the late phase, with progressive filling of the mesenteric-systemic collateral veins. |

| Venous Angioma | Obscure bleeding. | Globular enhancement. Sometimes, phleboliths within the lesions, which are more visible in the arterial phase. |

| [4] | ||

5. Lower Gastrointestinal Bleeding (LGIB)

| Clinical Presentation | CT Findings | |

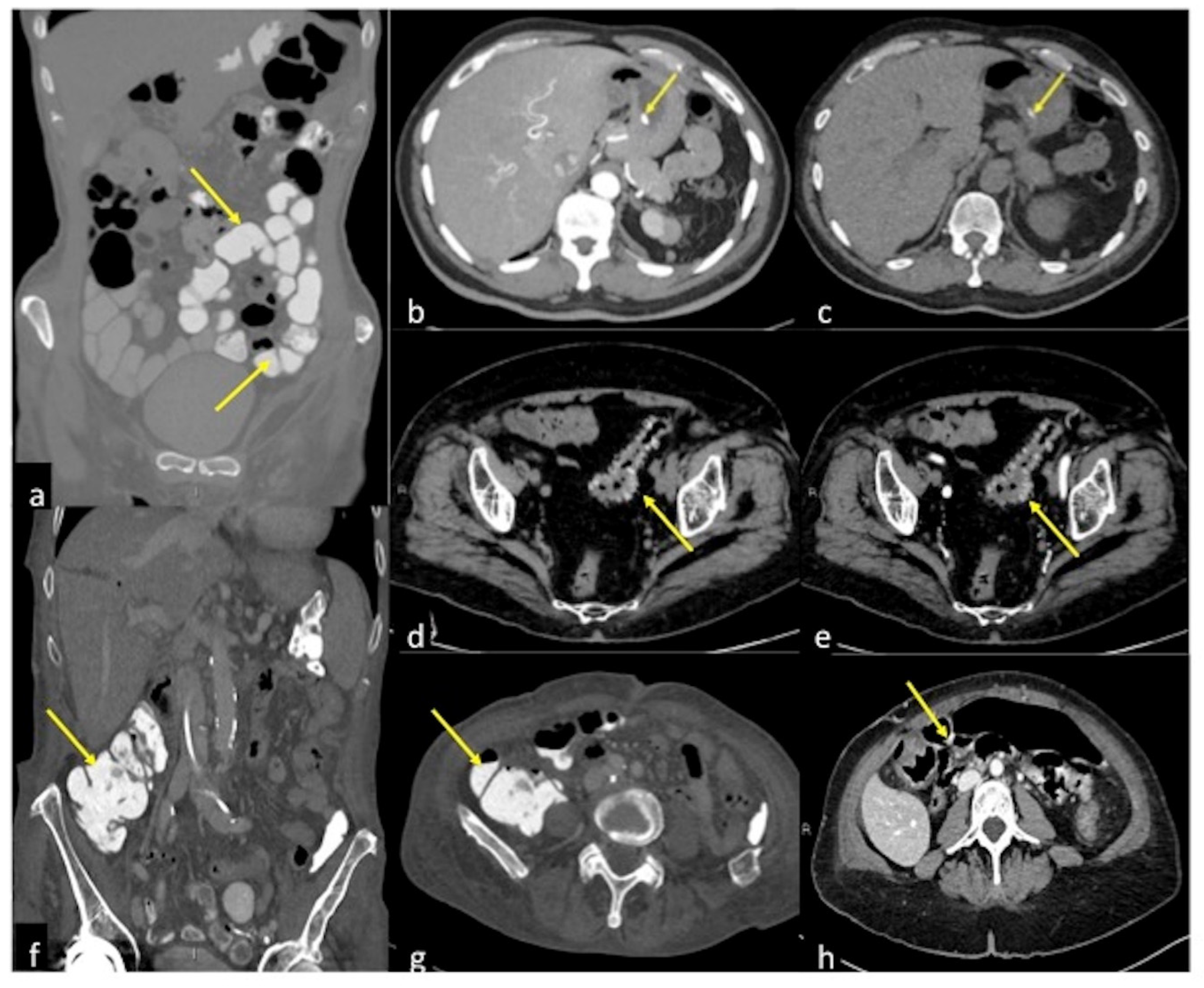

| Diverticulosis (Figure 33) | Asymptomatic or bleeding. | Protruding sacs where the vessels pass through the muscularis layer, between the mesenteric and antimesenteric taenia. |

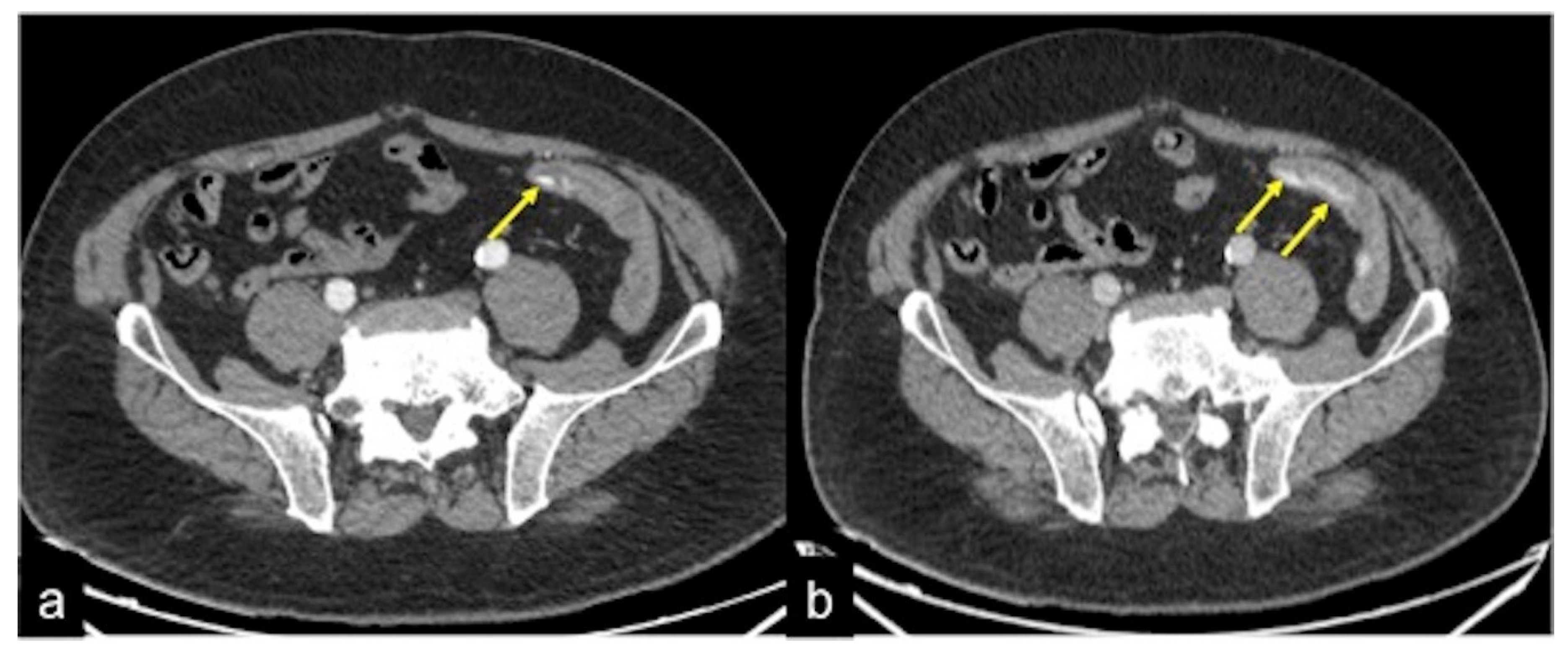

| Angiodysplasia (Figure 5 and Figure 34) | Asymptomatic or bleeding. | Small hyperdense nodules within the intestinal wall, best defined in the portal phase of the study. |

| Arterio-venous Malformation (Figure 17) | Haematochezia-rectorrhagia. | Vascular nidus with early opacification of the veins in the arterial phase. |

| Dieulafoy’s Lesion | Asymptomatic or bleeding. | Abnormally enlarged submucosal vessel, which may appear tortuous, linear or as a non-specific “blush” of contrast medium at the mucosal/submucosal level. |

| Rectal Varices and Haemorrhoids (Figure 35) | Pain and/or bleeding. | Dilated veins with possible bleeding visible in the portal phase; rectal varices are located proximal to the linea dentata while haemorrhoids are located in the anus. |

| Colorectal Cancer/Polyps (Figure 6, Figure 36, Figure 37 and Figure 38) | Bowel obstruction with or without bleeding. | Adenocarcinoma: irregular wall thickening with or without stenosis [25]; Polyps: mass-forming protrusions in the intestinal lumen with vascularised peduncle. |

| Inflammatory Bowel Disease (Figure 39 and Figure 40) | Haematochezia-rectorrhagia. | Acute: thickening of the walls, engorgement of the adjacent vasa recta, hyperaemia of the mucosa and infiltration of perirectal fat. Chronic: the colon and rectum are narrowed and shortened, without haustra, and with proliferation of the perirectal fat. |

| Colitis (Figure 41) | It depends on the aetiology. | Non-specific but associated with medical history, the clinical history and location of the lesions, it may be useful for diagnostic purposes. |

| [26,30] | ||

6. Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Patients Treated with Vascular Endothelial Growth Factor (VEGF) Inhibitors

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Farrell, J.J.; Friedman, L.S. Review article: The management of lower gastrointestinal bleeding. Aliment. Pharmacol. Ther. 2005, 21, 1281–1298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wortman, J.R.; Landman, W.; Fulwadhva, U.P.; Viscomi, S.G.; Sodickson, A.D. CT angiography for acute gastrointestinal bleeding: What the radiologist needs to know. Br. J. Radiol. 2017, 90, 20170076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guglielmo, F.F.; Wells, M.L.; Bruining, D.H.; Strate, L.L.; Huete, Á.; Gupta, A.; Soto, J.A.; Allen, B.C.; Anderson, M.A.; Brook, O.R.; et al. Gastrointestinal bleeding at CT angiography and CT enterography: Imaging atlas and glossary of terms. Radiographics 2021, 41, 1632–1656. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savides, T.J.; Jensen, D.M. Gastrointestinal Bleeding in Sleisenger and Fordtran’s Gastrointestinal and Liver Disease, 10th ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Geffroy, Y.; Rodallec, M.H.; Boulay-Coletta, I.; Jullès, M.C.; Ridereau-Zins, C.; Zins, M. Multidetector CT angiography in acute gastrointestinal bleeding: Why, when, and how. Radiographics 2011, 31, E35–E46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobellis, F.; Narese, D.; Berritto, D.; Brillantino, A.; Di Serafino, M.; Guerrini, S.; Grassi, R.; Scaglione, M.; Mazzei, M.A.; Romano, L. Large bowel ischemia/infarction: How to recognize it and make differential diagnosis? A review. Diagnostics 2021, 11, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Grezia, G.; Gatta, G.; Rella, R.; Iacobellis, F.; Berritto, D.; Musto, L.A.; Grassi, R. MDCT in acute ischaemic left colitis: A pictorial essay. La Radiol. Med. 2019, 124, 103–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobellis, F.; Berritto, D.; Fleischmann, D.; Gagliardi, G.; Brillantino, A.; Mazzei, M.A.; Grassi, R. CT Findings in Acute, Subacute, and Chronic Ischemic Colitis: Suggestions for Diagnosis. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 895248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saba, L.; Berritto, D.; Iacobellis, F.; Scaglione, M.; Castaldo, S.; Cozzolino, S.; Mazzei, M.A.; Di Mizio, V.; Grassi, R. Acute arterial mesenteric ischemia and reperfusion: Macroscopic and MRI findings, preliminary report. World J. Gastroenterol. 2013, 19, 6825–6833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobellis, F.; Berritto, D.; Somma, F.; Cavaliere, C.; Corona, M.; Cozzolino, S.; Fulciniti, F.; Cappabianca, S.; Rotondo, A.; Grassi, R. Magnetic resonance imaging: A new tool for diagnosis of acute ischemic colitis? World J. Gastroenterol. 2012, 18, 1496–1501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reginelli, A.; Iacobellis, F.; Berritto, D.; Gagliardi, G.; Di Grezia, G.; Rossi, M.; Fonio, P.; Grassi, R. Mesenteric ischemia: The importance of differential diagnosis for the surgeon. BMC Surg. 2013, 13, S51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carney, B.W.; Khatri, G.; Shenoy-Bhangle, A.S. The role of imaging in gastrointestinal bleed. Cardiovasc. Diagn. Ther. 2019, 9 (Suppl. 1), S88–S96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ACR Appropriateness Criteria for LGIB 2014. Available online: https://www.acr.org/Clinical-Resources/ACR-Appropriateness-Criteria (accessed on 1 April 2022).

- Wells, M.L.; Hansel, S.L.; Bruining, D.H.; Fletcher, J.G.; Froemming, A.T.; Barlow, J.M.; Fidler, J.L. CT for evaluation of acute gastrointestinal bleeding. Radiographics 2018, 38, 1089–1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Serafino, M.; Severino, R.; Laviani, F.; Maroscia, D. Three-dimensional computed tomography rendering of pedunculated colon polyp: New “clapper-bell” sign pedunculated polyp at 3D computed tomography. Radiol. Case Rep. 2016, 11, 292–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trabzonlu, T.A.; Mozaffary, A.; Kim, D.; Yaghmai, V. Dual-energy CT evaluation of gastrointestinal bleeding. Abdom. Radiol. 2020, 45, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parakh, A.; Macri, F.; Sahani, D. Dual-Energy Computed Tomography: Dose Reduction, Series Reduction, and Contrast Load Reduction in Dual-Energy Computed Tomography. Radiol. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 56, 601–624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artigas, J.M.; Martí, M.; Soto, J.A.; Esteban, H.; Pinilla, I.; Guillén, E. Multidetector CT angiography for acute gastrointestinal bleeding: Technique and findings. Radiographics 2013, 33, 1453–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stuber, T.; Hoffmann, M.H.; Stuber, G.; Klass, O.; Feuerlein, S.; Aschoff, A.J. Pitfalls in detection of acute gastrointestinal bleeding with multi-detector row helical CT. Abdom Imaging 2009, 34, 476–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Serafino, M.; Viscardi, D.; Iacobellis, F.; Giugliano, L.; Barbuto, L.; Oliva, G.; Ronza, R.; Borzelli, A.; Raucci, A.; Pezzullo, F.; et al. Computed tomography imaging of septic shock. Beyond the cause: The “CT hypoperfusion complex”. A pictorial essay. Insights Imaging 2021, 12, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gralnek, I.M.; Stanley, A.J.; Morris, A.J.; Camus, M.; Lau, J.; Lanas, A.; Laursen, S.B.; Radaelli, F.; Papanikolaou, I.S.; Cúrdia Gonçalves, T.; et al. Endoscopic diagnosis and management of nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage (NVUGIH): European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ESGE) Guideline—Update 2021. Endoscopy 2021, 53, 300–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Expert Panels on Vascular Imaging and Gastrointestinal Imaging; Singh-Bhinder, N.; Kim, D.H.; Holly, B.P.; Johnson, P.T.; Hanley, M.; Carucci, L.R.; Cash, B.D.; Chandra, A.; Gage, K.L.; et al. ACR Appropriateness Criteria ® Nonvariceal Upper Gastrointestinal Bleeding. J. Am. Coll Radiol. 2017, 14, S177–S188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Young, C.A.; Menias, C.O.; Bhalla, S.; Prasad, S.R. CT features of esophageal emergencies. Radiographics 2008, 28, 1541–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tonolini, M.; Ierardi, A.M.; Bracchi, E.; Magistrelli, P.; Vella, A.; Carrafiello, G. Non-perforated peptic ulcer disease: Multidetector CT findings, complications, and differential diagnosis. Insights Imaging 2017, 8, 455–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martino, A.; Bennato, R.; Oliva, G.; Pontarelli, A.; Picascia, D.; Romano, L.; Lombardi, G. Primary aortogastric fistula: An extraordinary rare endoscopic finding in the setting of upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Endoscopy 2021, 53, E60–E61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davila, R.E.; Rajan, E.; Adler, D.G.; Egan, J.; Hirota, W.K.; Leighton, J.A.; Qureshi, W.; Zuckerman, M.J.; Fanelli, R.; Wheeler-Harbaugh, J.; et al. ASGE Guideline: The role of endoscopy in the patient with lower-GI bleeding. Gastrointest. Endosc. 2005, 62, 656–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iacobellis, F.; Perillo, A.; Iadevito, I.; Tanga, M.; Romano, L.; Grassi, R.; Nicola, R.; Scaglione, M. Imaging of Oncologic Emergencies. Semin. Ultrasound CT MRI 2018, 39, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Serafino, M.; Mercogliano, C.; Vallone, G. Ultrasound evaluation of the enteric duplication cyst: The gut signature. J. Ultrasound 2015, 19, 131–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Esposito, F.; Di Serafino, M.; Mercogliano, C.; Ferrara, D.; Vezzali, N.; Di Nardo, G.; Martemucci, L.; Vallone, G.; Zeccolini, M. The pediatric gastrointestinal tract: Ultrasound findings in acute diseases. J. Ultrasound 2019, 22, 409–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federle, M.P.; Brooke, J.R.; Woodward, P.J.; Borhani, A.A. Diagnostic Imaging: Abdomen Lippincott, 2nd ed.; Williams & Wilkins: Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 2010; 1288p. [Google Scholar]

- Fischbach, W. Medikamenteninduzierte gastrointestinale Blutung [Drug-induced gastrointestinal bleeding]. Internist 2019, 60, 597–607. (In Germany) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elice, F.; Rodeghiero, F. Side effects of anti-angiogenic drugs. Thromb Res. 2012, 129 (Suppl. 1), S50–S53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hang, X.F.; Xu, W.S.; Wang, J.X.; Wang, L.; Xin, H.G.; Zhang, R.Q.; Ni, W. Risk of high-grade bleeding in patients with cancer treated with bevacizumab: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2011, 67, 613–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohtsu, A.; Shah, M.A.; Van Cutsem, E.; Rha, S.Y.; Sawaki, A.; Park, S.R.; Lim, H.Y.; Yamada, Y.; Wu, J.; Langer, B.; et al. Bevacizumab in combination with chemotherapy as first-line therapy in advanced gastric cancer: A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled phase III study. J. Clin. Oncol. 2011, 29, 3968–3976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kilickap, S.; Abali, H.; Celik, I. Bevacizumab, bleeding, thrombosis, and warfarin. J. Clin. Oncol. 2003, 21, 3542, author reply 3543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Clinical Terminology by Type of Gastrointestinal Bleeding | |

|---|---|

| UGIB | Upper gastrointestinal haemorrhage—proximal to the Treitz ligament (oesophagus, stomach and duodenum). |

| LGIB | Lower GI haemorrhage—distal to the Treitz ligament (colon and rectum). |

| SBB/MGIB | Middle gastrointestinal haemorrhage—distal to the ampulla of Vater and proximal to the ileocaecal valve (small intestine). |

| Suspected SBB | Gastrointestinal haemorrhage in which no source of bleeding is identified after performing both upper and lower endoscopy. |

| Obscure GIB | Gastrointestinal haemorrhage in which no source of bleeding is identified after the entire gastrointestinal tract has been fully evaluated with both endoscopic and advanced imaging techniques. Obscure gastrointestinal bleeding can be overt or occult depending on whether evident gastrointestinal bleeding is clinically present. |

| Overt GIB | Visible gastrointestinal bleeding such as haematemesis, haematochezia or melaena. The definition of overt haemorrhage is preferable to that of acute haemorrhage because the latter only defines the onset of symptoms and not the visibility of the bleeding itself. In addition, patients with overt GIB may present acutely, but also intermittently or for a prolonged period. |

| Occult GIB | Gastrointestinal bleeding that is not clinically visible. Patients with occult gastrointestinal bleeding have a positive faecal occult blood test or iron deficiency anaemia with no apparent cause. |

| Massive GIB | Gastrointestinal bleeding associated with hemodynamic instability (e.g., hypotension with systolic blood pressure <90 mmHg, tachycardia, symptoms of pre-shock or shock) or bleeding that requires transfusion of more than 4 units of packed red blood cells in 24 h. |

| Haematemesis | This term refers to the vomiting of blood and is indicative of bleeding from the oesophagus, stomach or duodenum. Haematemesis includes the vomiting of bright red blood, which suggests recent or current blood loss, and vomiting of coffee-like material (coffee grounds vomiting) which suggests the bleeding stopped some time ago. |

| Melaena | It consists of black liquid stools resulting from the breakdown of blood into haematin or other haemoglobin components by intestinal bacteria. Melaena is the manifestation of bleeding that originates from the upper GI tract, the small intestine, or the proximal portion of the large intestine. It generally occurs when 50 to 100 mL or more of blood (usually from the upper GI tract) is present in the alimentary canal, with characteristic stool passed a few hours after the bleeding event. |

| Haematochezia | It consists of bright red blood evacuated from the rectum and suggests active bleeding from the proximal GI tract, small intestine, distal colon or anorectal area. |

| Rectorrhagia | It consists of severe bleeding from the distal GI tract. |

| Recommendations | Advantages | Disadvantages | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Endoscopy | Initial procedure for the diagnosis and treatment of UGIB and LIGB in haemodynamically stable patients. | Locates the source of bleeding and allows for haemostatic treatment in most patients. Tissue samples can be taken in the event of suspected malignancy. | It may not be universally available. Limitations in terms of the visualisation of the whole small intestine. Diagnostic exploration limited by the presence of abundant active bleeding, food residues and faeces. |

| Enteroscopy and Videocapsule Endoscopy (VDE) | Possible diagnostic use in the detection of focal SBB/MGIB and LGIB bleeds in haemodynamically stable patients. Endoscopic procedures, such as single or double balloon enteroscopy or retrograde ileoscopy may be indicated to define the diagnosis and treatment if the source of bleeding was found with the VDC. | Visualises the small intestine mucosa directly with the ability to identify a potential source of active bleeding. | Enteroscopy: an invasive procedure that requires sedation. Risk of perforation. Need for specialised staff and level II centres. It is not used in UGIB. VDC: long duration of examination and analysis time of acquired images (>8 h); furthermore, it does not allow for therapeutic haemostasis. Need for specialised staff and level II centres. It is not used in UGIB. |

| Scintigraphy | Possible diagnostic use in the search for focal SBB/MGIB and LGIB in haemodynamically stable patients. | It can detect low rates of arterial or venous bleeding, including intermittent. Non-invasive. No bowel preparation required. | Often, it does not allow for the exact identification of the bleeding site. High radiation dose applied. It requires time and specialised staff that are not available in urgent contexts. It is not used in UGIB. |

| Angiography | Possible diagnostic use in the screening for focal SBB/MGIB and LGIB in haemodynamically stable patients. Recurrent/continuous bleeding after colonoscopic treatment for LGIB. For UGIB, patients with acute bleeding with negative endoscopy or in whom endoscopy could not find the source (especially haemodynamically unstable patients). Possible therapeutic use for focal UGIB, MGIB and LGIB that cannot be treated endoscopically. | It can identify and treat gastrointestinal bleeding, if detected, also allowing for the selective exclusion of small vessels. High spatial resolution. | It requires a high bleeding rate for detection of the bleeding source. Invasive and time-consuming procedure for diagnostic purposes. High radiation dose applied. Requires the use of contrast media. Risk of bowel wall ischaemia [6,7,8]. Need for specialised staff and level II centres [9,10,11]. |

| Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) | Possible use for diagnosis and follow-up of IBD. Not indicated for the detection of active GI bleeding. Non-routine use in occult bleeding and obscure SBB/MGIB in haemodynamically stable patients. | High contrast and spatial resolution. Possibility of using ultra-fast sequences to examine intestinal motility (cine-MRI). No ionising radiation. | Not widely available. Long procedure. Need for proper preparation. Use of contrast media. Not therapeutic. It is not used in UGIB. |

| CT | The technique of choice for all SBB/MGIB and LGIB with active bleeding in hemodynamically stable (or stabilised) patients; UGIB with negative endoscopy, or endoscopy unable to identify the source (comparable to angiography). | Widely available. Quick identification of the bleeding source with precise anatomical localisation. Containment of the radiation dose with advanced technology (dual energy). | It may be less sensitive than radionuclide imaging. It can underestimate intermittent bleeding. Not therapeutic. Radiation dose. Requires the use of contrast medium. |

| Overt GIB—CTA Protocol | Occult GIB or SBB—CTE Protocol | |

| IV administration of contrast medium | 80–130 mL of high-concentration iodinated contrast medium (370–400 mgI/mL) | 80–130 mL of high-concentration iodinated contrast medium (370–400 mgI/mL) |

| Speed of administration | The highest possible flow (3.5–4 mL/s) through an 18G cannula | The highest possible flow (3.5–4 mL/s) through an 18G cannula |

| Normal saline | 40 mL of high-flow normal saline | 40 mL of high-flow normal saline |

| Oral administration of contrast medium | Not recommended | 1350–1500 mL of fractionated neutral oral contrast agent starting about 1 h prior to the examination |

| Scanned area | From the diaphragm to the pubic symphysis (possible extension to the chest) | From the diaphragm to the pubic symphysis |

| Phases of acquisition | Multiphase CT technique: Without contrast or virtual no contrast Arterial phase (bolus tracking technique) Venous phase (70–90 s after injection) Optional late phase (5 min after injection) | Multiphase CT technique: Without contrast or virtual no contrast Late arterial phase (10 s after bolus trigger) Enteric phase (50 s after injection) Late venous phase (90 s after injection) Alternative technique: split bolus protocols may be adopted |

| Post-processing | 2.5–3 mm axial slices for each series (optional 1 mm axial) Coronal and sagittal reconstruction of 2.5–3 mm images (50% overlap) Optional maximum intensity projection and volumetric reconstruction | 2.5–3 mm axial slices for each series (optional 1 mm axial) Coronal and sagittal reconstruction of 2.5–3 mm images (50% overlap) Optional maximum intensity projection and volumetric reconstruction |

| DECTA post-processing | 40–60 keV (i.e., virtual monoenergetic), iodine density, virtual non-contrast and standard mixed series | 40–60 keV (i.e., virtual monoenergetic), iodine density, virtual non-contrast and standard mixed series |

| FALSE NEGATIVE | |

| Pitfall | Prevention Strategy |

| Fluid-filled dilated bowel | No positive or negative contrast media administration (Figure 19) |

| Low flow rate of contrast media administration | Rigorous CTA/DECTA examination technique; post-processing reconstructions (Figure 11 and Figure 14) |

| Low-flow bleeding or reduced cardiac function/hypovolaemic or septic shock etc. | CTA/DECTA late venous phase; post-processing reconstruction (Figure 4 and Figure 9) |

| FALSE POSITIVE | |

| Pitfall | Prevention Strategy |

| Suture material, clips, foreign bodies | Unenhanced CTA scan; virtual unenhanced DECTA reconstruction; DECTA iodine map (Figure 2, Figure 7, Figure 8, Figure 16 and Figure 19) |

| Retained contrast media within the lumen after previous contrast media administration | Unenhanced CTA scan; virtual unenhanced DECTA reconstruction (Figure 19) |

| Cone-beam artefacts | Rigorous CTA/DECTA examination technique; post-processing reconstructions (Figure 19) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Di Serafino, M.; Iacobellis, F.; Schillirò, M.L.; Dell’Aversano Orabona, G.; Martino, A.; Bennato, R.; Borzelli, A.; Oliva, G.; D’Errico, C.; Pezzullo, F.; et al. The Role of CT-Angiography in the Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Pictorial Essay of Active and Obscure Findings. Tomography 2022, 8, 2369-2402. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography8050198

Di Serafino M, Iacobellis F, Schillirò ML, Dell’Aversano Orabona G, Martino A, Bennato R, Borzelli A, Oliva G, D’Errico C, Pezzullo F, et al. The Role of CT-Angiography in the Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Pictorial Essay of Active and Obscure Findings. Tomography. 2022; 8(5):2369-2402. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography8050198

Chicago/Turabian StyleDi Serafino, Marco, Francesca Iacobellis, Maria Laura Schillirò, Giuseppina Dell’Aversano Orabona, Alberto Martino, Raffaele Bennato, Antonio Borzelli, Gaspare Oliva, Chiara D’Errico, Filomena Pezzullo, and et al. 2022. "The Role of CT-Angiography in the Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Pictorial Essay of Active and Obscure Findings" Tomography 8, no. 5: 2369-2402. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography8050198

APA StyleDi Serafino, M., Iacobellis, F., Schillirò, M. L., Dell’Aversano Orabona, G., Martino, A., Bennato, R., Borzelli, A., Oliva, G., D’Errico, C., Pezzullo, F., Barbuto, L., Ronza, R., Ponticiello, G., Corvino, F., Giurazza, F., Lombardi, G., Niola, R., & Romano, L. (2022). The Role of CT-Angiography in the Acute Gastrointestinal Bleeding: A Pictorial Essay of Active and Obscure Findings. Tomography, 8(5), 2369-2402. https://doi.org/10.3390/tomography8050198