Ethics of Psychedelic Use in Psychiatry and Beyond—Drawing upon Legal, Social and Clinical Challenges

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Methods

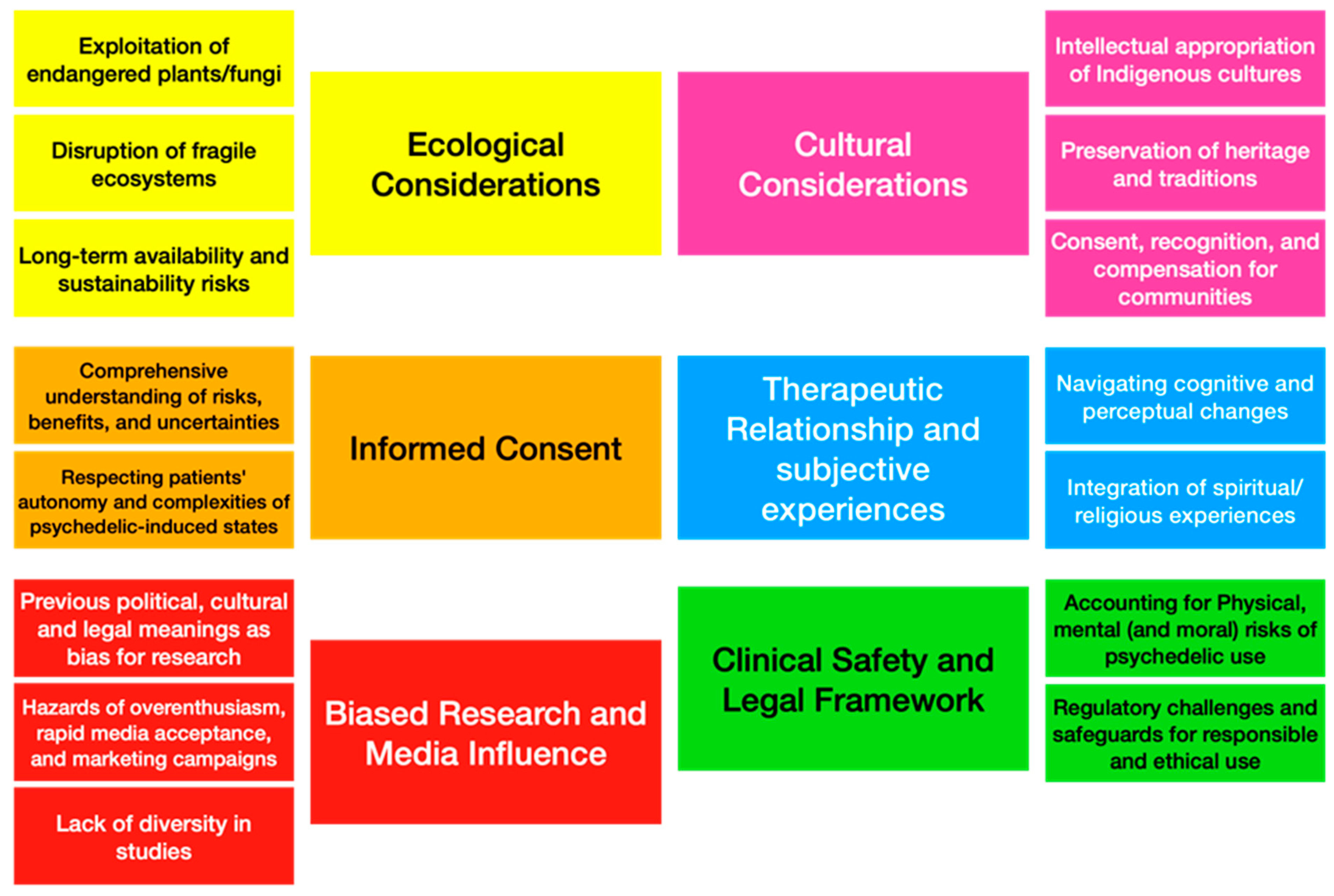

3. Discussion of the Analysis

3.1. Ecological and Cultural Considerations

3.2. Informed Consent

3.3. Biased Research and Media Influence

3.4. Therapeutic Relationship and Subjective Experiences

3.5. Safety and Legal Framework

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Thematic Analysis

| Theme | Ecological Considerations | Informed Consent | Biased Research and Media Influence | Cultural Considerations | Therapeutic Relation and Subjective Experience | Clinical Safety and Legal Framework | |||||||||

| Sub-Theme | Exploitation of Endangered Plants | Disruption of Fragile Ecosystems | Long-Term Availability and Sustainability | Understanding Risks, Benefits, and Uncertainties | Respecting Patients Autonomy | Previous Political, Cultural, and Legal Meanings Impact on Research | Hazards of Overenthusiasm, Rapid Media Acceptance, and Marketing Campaigns | Lack of Diversity in Studies | Intellectual Appropriation | Preservation of Heritages and Traditions | Consent, Recognition, and Compensation of Communities | Navigating Cognitive and Perceptual Changes | Integration of Spiritual and Religious Experiences | Accounting For Physical, Mental, and Moral Risks of Use | Regulatory Challenges and Safeguards for Responsible and Ethical Use |

| (Miceli McMillan, 2022) | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| (Cusimano, 2022) | x | ||||||||||||||

| (Greif and Šurkala, 2020) | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| (Plesa and Petranker, 2022) | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| (Rucker and Young, 2021) | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| (Johnson, 2020) | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| (Bodnár and Kakuk, 2019) | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| (Miceli McMillan, 2020) | x | x | |||||||||||||

| (Langlitz et al., 2021) | x | x | x | x | x | x | |||||||||

| (Smith and Appelbaum, 2022) | x | x | x | x | x | ||||||||||

| (Letheby, 2022) | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| (Hauskeller et al., 2022) | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| (Stauffer et al., 2022) | x | ||||||||||||||

| (Miceli McMillan, 2021) | x | x | |||||||||||||

| (Mintz et al., 2022) | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| (Kious et al., 2022) | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| (Petranker et al., 2020) | x | x | |||||||||||||

| (Pilecki et al., 2021) | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| (van Amsterdam et al., 2021) | X | ||||||||||||||

| (Schleim, 2022) | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| (Williams et al., 2021) | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| (Page L. A. et al., 2021) | X | ||||||||||||||

| (Marcus, 2022) | X | X | X | X | X | X | |||||||||

| (Gerber et al., 2021) | X | X | X | ||||||||||||

| (Mocanu et al., 2022) | X | ||||||||||||||

| (Askew and Williams, 2021) | X | X | |||||||||||||

| (Thal et al., 2021) | X | X | X | X | |||||||||||

| (Yaden et al., 2020) | X | X | |||||||||||||

| (Campbell and Williams, 2021) | x | ||||||||||||||

| (Smith and Appelbaum, 2021) | x | ||||||||||||||

| (Mathai et al., 2022) | x | x | |||||||||||||

| (Žuljević et al., 2022) | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| (Peterson et al., 2019) | x | x | |||||||||||||

| (Levin et al., 2022) | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| (Corrigan et al., 2022) | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| (Michaels et al., 2018) | x | ||||||||||||||

| (Phelps, 2017) | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| (Smith and Sisti, 2021) | x | x | x | x | |||||||||||

| (Brennan et al., 2021) | x | x | |||||||||||||

| (Dupuis, 2021) | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| (Eleftheriou and Thomas, 2021) | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

| (Kuypers et al., 2019) | x | x | x | ||||||||||||

Appendix B. Classification of the Studies Included

| References | Abstract/ Title | Introduction/Aims | Data Collection | Sampling | Analysis | Ethics/Bias | Results | Generability | Implications | Total | Grade |

| (Miceli McMillan, 2022) | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 25 | B |

| (Cusimano, 2022) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 32 | A |

| (Greif and Šurkala, 2020) | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 25 | B |

| (Plesa and Petranker, 2022) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 29 | B |

| (Rucker and Young, 2021) | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 24 | B |

| (Johnson, 2020) | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 24 | B |

| (Bodnár and Kakuk, 2019) | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 32 | A |

| (Miceli McMillan, 2020) | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 25 | B |

| (Langlitz et al., 2021) | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 26 | B |

| (Smith and Appelbaum, 2022) | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 28 | B |

| (Letheby, 2022) | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 28 | B |

| (Hauskeller et al., 2022) | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 25 | B |

| (Stauffer et al., 2022) | 3 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 32 | A |

| (Miceli McMillan, 2021) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 27 | B |

| (Mintz et al., 2022) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 28 | B |

| (Kious et al., 2022) | 4 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 28 | B |

| (Petranker et al., 2020) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 28 | B |

| (Pilecki et al., 2021) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 28 | B |

| (van Amsterdam et al., 2021) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 35 | A |

| (Schleim, 2022) | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 25 | B |

| (Williams et al., 2021) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 30 | A |

| (Page L. A. et al., 2021) | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 30 | A |

| (Marcus, 2022) | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 26 | B |

| (Gerber et al., 2021) | 3 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 26 | B |

| (Mocanu et al., 2022) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 28 | B |

| (Askew and Williams, 2021) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 34 | A |

| (Thal et al., 2021) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 29 | B |

| (Yaden et al., 2020) | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 24 | B |

| (Campbell and Williams, 2021) | 4 | 3 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 24 | B |

| (Smith and Appelbaum, 2021) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 26 | B |

| (Mathai et al., 2022) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 35 | A |

| (Žuljević et al., 2022) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 34 | A |

| (Peterson et al., 2019) | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 34 | A |

| (Levin et al., 2022) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 30 | A |

| (Corrigan et al., 2022) | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 35 | A |

| (Michaels et al., 2018) | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 32 | A |

| (Phelps, 2017) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 32 | A |

| (Smith and Sisti, 2021) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 1 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 29 | B |

| (Brennan et al., 2021) | 4 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 29 | B |

| (Dupuis, 2021) | 4 | 4 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 33 | A |

| (Eleftheriou and Thomas, 2021) | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 29 | B |

| (Kuypers et al., 2019) | 4 | 4 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 30 | A |

Appendix C. Hawker´s Tool for Studies Quality Appraisal

| 1. Abstract and title: Did they provide a clear description of the study? | Good: structured abstract with full information and clear title |

| Fair: abstract with most of the information. | |

| Poor: inadequate abstract. | |

| Very poor: no abstract. | |

| 2. Introduction and aims: Was there a good background section and clear statement of the aims of the research? | Good: full but concise background to discussion/study containing up-to-date literature review and highlighting gaps in knowledge; clear statement of aim AND objectives including research questions. |

| Fair: some background and literature review; research questions outlined. | |

| Poor: some background but no aim/objectives/questions OR aims/objectives but inadequate background. | |

| Very poor: no mention of aims/objectives; no background or literature review. | |

| 3. Method and data: Are the methods appropriate and clearly explained? | Good: method is appropriate and described clearly (e.g., questionnaires included); clear details of the data collection and recording. |

| Fair: method appropriate, description could be better; data described. | |

| Poor: questionable whether the method is appropriate; method described inadequately; little description of data. | |

| Very poor: no mention of method AND/OR method inappropriate AND/OR no details of data. | |

| 4. Sampling: Was the sampling strategy appropriate to address the aims? | Good: details (age/gender/race/context) of who was studied and how they were recruited and why this group was targeted; the sample size was justified for the study; response rates shown and explained. |

| Fair: sample size justified; most information given but some missing. | |

| Poor: sampling mentioned but few descriptive details. | |

| Very poor: no details of the sample. | |

| 5. Data analysis: Was the description of the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Good: clear description of how the analysis was carried out. Qualitative studies: Description of how themes derived/respondent validation or triangulation. Quantitative studies: Reasons for tests selected hypothesis driven/numbers add up/statistical significance discussed. |

| Fair: descriptive discussion of the analysis. | |

| Poor: minimal details about analysis. | |

| Very poor: no discussion of the analysis. | |

| 6. Ethics and bias: Have ethical issues been addressed and has necessary ethical approval been gained? Has the relationship between researchers and participants been adequately considered? | Good: ethics: when necessary, issues of confidentiality, sensitivity, and consent were addressed; bias: researcher was reflexive and/or aware of own bias. |

| Fair: lip service was paid to the above (i.e., these issues were acknowledged). | |

| Poor: brief mention of issues. | |

| Very poor: no mention of issues. | |

| 7. Results: Is there a clear statement of the findings? | Good: findings are explicit, easy to understand, and in a logical progression; tables, if present, are explained in text; results relate directly to aims; sufficient data are presented to support findings. |

| Fair: findings mentioned but more explanation could be given; data presented relate directly to results. | |

| Poor: findings presented haphazardly, not explained, and do not progress logically from results. | |

| Very poor: findings not mentioned or do not relate to aims. | |

| 8. Transferability or generalisability: Are the findings of this study transferable (generalisable) to a wider population? | Good: context and setting of the study are described sufficiently to allow comparison with other contexts and settings, plus a high score in Q4 (sampling). |

| Fair: some context and setting described but more needed to replicate or compare the study with others, plus a fair score or higher in Q4. | |

| Fair: some context and setting described but more needed to replicate or compare the study with others, plus a fair score or higher in Q4. | |

| Very poor: no description of context/setting. | |

| 9. Implications and usefulness. How important are these findings to policy and practice? | Good: contributes something new and/or different in terms of understanding/insight or perspective; suggests ideas for further research; suggests implications for policy and/or practice. |

| Fair: two of the above. | |

| Poor: only one of the above. | |

| Very poor: none of the above. |

References

- Solmi, M.; Chen, C.; Daure, C.; Buot, A.; Ljuslin, M.; Verroust, V.; Mallet, L.; Khazaal, Y.; Rothen, S.; Thorens, G.; et al. A century of research on psychedelics: A scientometric analysis on trends and knowledge maps of hallucinogens, entactogens, entheogens and dissociative drugs. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022, 64, 44–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ClinicalTrials.gov. Search of Psychedelic; Hallucinogen|Phase 1, 2, 3—Results on Map. 2022. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/results/map?term=psychedelic%3B+hallucinogen&phase=012&map= (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Johnson, M.W.; Garcia-Romeu, A.; Griffiths, R.R. Long-term follow-up of psilocybin-facilitated smoking cessation. Am. J. Drug Alcohol Abus. 2016, 43, 55–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schatzberg, A.F. Development of New Psychopharmacological Agents for Depression and Anxiety. Psychiatr. Clin. N. Am. 2015, 38, 379–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krystal, J.H.; Davis, L.L.; Neylan, T.C.; Raskind, M.A.; Schnurr, P.P.; Stein, M.B.; Vessicchio, J.; Shiner, B.; Gleason, T.D.; Huang, G.D. It Is Time to Address the Crisis in the Pharmacotherapy of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder: A Consensus Statement of the PTSD Psychopharmacology Working Group. Biol. Psychiatry 2017, 82, e51–e59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rush, A.J.; Trivedi, M.H.; Wisniewski, S.R.; Nierenberg, A.A.; Stewart, J.W.; Warden, D.; Niederehe, G.; Thase, M.E.; Lavori, P.W.; Lebowitz, B.D.; et al. Acute and Longer-Term Outcomes in Depressed Outpatients Requiring One or Several Treatment Steps: A STAR*D Report. Am. J. Psychiatry 2006, 163, 1905–1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Saveanu, R.; Etkin, A.; Duchemin, A.-M.; Goldstein-Piekarski, A.; Gyurak, A.; Debattista, C.; Schatzberg, A.F.; Sood, S.; Day, C.V.; Palmer, D.M.; et al. The International Study to Predict Optimized Treatment in Depression (iSPOT-D): Outcomes from the acute phase of antidepressant treatment. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2014, 61, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carhart-Harris, R.L.; Roseman, L.; Bolstridge, M.; Demetriou, L.; Pannekoek, J.N.; Wall, M.B.; Tanner, M.; Kaelen, M.; McGonigle, J.; Murphy, K.; et al. Psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression: fMRI-measured brain mechanisms. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 13187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, M.; Richards, W.; Griffiths, R. Human hallucinogen research: Guidelines for safety. J. Psychopharmacol. 2008, 22, 603–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.E. Hallucinogens. Pharmacol. Ther. 2004, 101, 131–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katzung, B.G. Chapter 32: Drugs of Abuse. In Basic & Clinical Pharmacology, 13th ed.; Education, M.H., Ed.; Lange: New York, NY, USA, 2017; pp. 552–566. [Google Scholar]

- Lüscher, C.; Ungless, M.A. The Mechanistic Classification of Addictive Drugs. PLoS Med. 2006, 3, e437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ermakova, A.O.; Dunbar, F.; Rucker, J.; Johnson, M.W. A narrative synthesis of research with 5-MeO-DMT. J. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 36, 273–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McIntyre, R.S.; Rosenblat, J.D.; Nemeroff, C.B.; Sanacora, G.; Murrough, J.W.; Berk, M.; Brietzke, E.; Dodd, S.; Gorwood, P.; Ho, R.; et al. Synthesizing the Evidence for Ketamine and Esketamine in Treatment-Resistant Depression: An International Expert Opinion on the Available Evidence and Implementation. Am. J. Psychiatry 2021, 178, 383–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Swainson, J.; Thomas, R.K.; Archer, S.; Chrenek, C.; Mackay, A.; Baker, G.; Dursun, S.; Klassen, L.J.; Chokka, P.; Swainson, J.; et al. Expert Review of Neurotherapeutics Esketamine for treatment resistant depression. Expert Rev. Neurother. 2019, 19, 899–911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morton, J. Ecstasy: Pharmacology and neurotoxicity. Curr. Opin. Pharmacol. 2005, 5, 79–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasser, P.; Kirchner, K.; Passie, T. LSD-assisted psychotherapy for anxiety associated with a life-threatening disease: A qualitative study of acute and sustained subjective effects. J. Psychopharmacol. 2014, 29, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, Y.; Liechti, M.E. Long-lasting subjective effects of LSD in normal subjects. Psychopharmacology 2017, 235, 535–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogenschutz, M.P.; Forcehimes, A.A. Development of a Psychotherapeutic Model for Psilocybin-Assisted Treatment of Alcoholism. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2016, 57, 389–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogenschutz, M.P. Studying the Effects of Classic Hallucinogens in the Treatment of Alcoholism: Rationale, Methodology, and Current Research with Psilocybin. Curr. Drug Abus. Rev. 2013, 6, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths Roland, R.; Johnson, M.W.; Carducci, M.A.; Umbricht, A.; Richards, W.A.; Richards, B.D.; Cosimano, M.P.; Klinedinst, M.A. Psilocybin produces substantial and sustained decreases in depression and anxiety in patients with life-threatening cancer: A randomized double-blind trial. J. Psychopharmacol. 2016, 30, 1181–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MAPS Public Benefit Corporation. MAPS MDMA Therapy Training Program. 2022. Available online: https://mapspublicbenefit.com/training/about-the-program/ (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The prisma 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Med. Flum. 2021, 57, 444–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawker, S.; Payne, S.; Kerr, C.; Hardey, M.; Powell, J. Appraising the Evidence: Reviewing Disparate Data Systematically. Qual. Health Res. 2002, 12, 1284–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McMillan, R.M. Psychedelic injustice: Should bioethics tune in to the voices of psychedelic-using communities? Med. Humanit. 2022, 48, 269–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ko, K.; Knight, G.; Rucker, J.J.; Cleare, A.J. Psychedelics, Mystical Experience, and Therapeutic Efficacy: A Systematic Review. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 917199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, R.M. Global bioethical challenges of medicalising psychedelics. J. Psychedelic Stud. 2021, 5, 57–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerber, K.; Flores, I.G.; Ruiz, A.C.; Ali, I.; Ginsberg, N.L.; Schenberg, E.E. Ethical Concerns about Psilocybin Intellectual Property. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2021, 4, 573–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. Trends Sci. 2002, 7, 44–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langlitz, N.; Dyck, E.; Scheidegger, M.; Repantis, D. Moral Psychopharmacology Needs Moral Inquiry: The Case of Psychedelics. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 680064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letheby, C.; Mattu, J. Philosophy and classic psychedelics: A review of some emerging themes. J. Psychedelic Stud. 2022, 5, 166–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcus, O. Everybody’s creating it along the way’: Ethical tensions among globalized ayahuasca shamanisms and therapeutic integration practices. Interdiscip. Sci. Rev. 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilecki, B.; Luoma, J.B.; Bathje, G.J.; Rhea, J.; Narloch, V.F. Ethical and legal issues in psychedelic harm reduction and integration therapy. Harm Reduct. J. 2021, 18, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.R.; Appelbaum, P.S. Novel ethical and policy issues in psychiatric uses of psychedelic substances. Neuropharmacology 2022, 216, 109165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mathai, D.S.; Lee, S.M.; Mora, V.; O’Donnell, K.C.; Garcia-Romeu, A.; Storch, E.A. Mapping consent practices for outpatient psychiatric use of ketamine. J. Affect. Disord. 2022, 312, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodnár, K.J.; Kakuk, P. Research ethics aspects of experimentation with LSD on human subjects: A historical and ethical review. Med. Health Care Philos. 2018, 22, 327–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greif, A.; Šurkala, M. Compassionate use of psychedelics. Med. Health Care Philos. 2020, 23, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, M.W. Consciousness, Religion, and Gurus: Pitfalls of Psychedelic Medicine. ACS Pharmacol. Transl. Sci. 2020, 4, 578–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thal, S.B.; Bright, S.J.; Sharbanee, J.M.; Wenge, T.; Skeffington, P.M. Current Perspective on the Therapeutic Preset for Substance-Assisted Psychotherapy. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 617224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mintz, K.T.; Gammer, B.; Khan, A.J.; Shaub, G.; Levine, S.; Sisti, D. Physical Disability and Psychedelic Therapies: An Agenda for Inclusive Research and Practice. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 914458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yaden, D.B.; Sciences, B.; Yaden, M.E.; Griffiths, R.R.; Sciences, B. Psychedelics in Psychiatry—Keeping the Renaissance from Going off the Rails. JAMA Psychiatry 2022, 78, 469–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. WMA Declaration of Helsinki: Ethical Principles for Medical Research Involving Human Subjects. Available online: http://www.wma.net/en/30publications/10policies/b3/index.html (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Kious, B.; Schwartz, Z.; Lewis, B. Should we be leery of being Leary? Concerns about psychedelic use by psychedelic researchers. J. Psychopharmacol. 2022, 37, 45–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCoy, M.S.; Emanuel, E.J. Why There Are No “Potential” Conflicts of Interest. JAMA 2017, 317, 1721–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lattin, D. The Harvard Psychedelic Club: How Timothy Leary, Ram Dass, Huston Smith, and Andrew Weil Killed the Fifties and Ushered in a New Age for America; HarperOne/HarperCollins: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Metzner, R. Hallucinogenic Drugs and Plants in Psychotherapy and Shamanism. J. Psychoact. Drugs 1998, 30, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Forstmann, M.; Sagioglou, C. How psychedelic researchers’ self-admitted substance use and their association with psychedelic culture affect people’s perceptions of their scientific integrity and the quality of their research. Public Underst. Sci. 2020, 30, 302–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plesa, P.; Petranker, R. Manifest your desires: Psychedelics and the self-help industry. Int. J. Drug Policy 2022, 105, 103704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muthukumaraswamy, S.D.; Forsyth, A.; Lumley, T. Blinding and expectancy confounds in psychedelic randomized controlled trials. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2021, 14, 1133–1152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Petranker, R.; Anderson, T.; Farb, N. Psychedelic Research and the Need for Transparency: Polishing Alice’s Looking Glass. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetlock, P.E.; Mitchell, G. Implicit Bias and Accountability Systems: What Must Organizations Do to Prevent Discrimination? Res. Organ. Behav. 2009, 29, 3–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuypers KP, C.; Ng, L.; Erritzoe, D.; Knudsen, G.M.; Nichols, C.D.; Nichols, D.E.; Pani, L.; Soula, A.; Nutt, D. Microdosing psychedelics: More questions than answers? An overview and suggestions for future research. J. Psychopharmacol. 2019, 33, 1039–1057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phelps, J. Developing Guidelines and Competencies for the Training of Psychedelic Therapists. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2017, 57, 450–487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.L.; Korevaar, D.; Harvey, R.; Fitzgerald, P.B.; Liknaitzky, P.; O’Carroll, S.; Puspanathan, P.; Ross, M.; Strauss, N.; Bennett-Levy, J. Translating Psychedelic Therapies From Clinical Trials to Community Clinics: Building Bridges and Addressing Potential Challenges Ahead. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 737738. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Council on Spiritual Practices. Code of Ethics for Spiritual Guides. 2001. Available online: https://csp.org/docs/code-of-ethics-for-spiritual-guides (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- MAPS. MAPS Code of Ethics for Psychedelic Psychotherapy. MAPS Bulletin Special Edition 2019, 29, 24–27. Available online: https://maps.org/news/bulletin/maps-bulletin-spring-2019-vol-29-no-1/ (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Michaels, T.I.; Purdon, J.; Collins, A.; Williams, M.T. Inclusion of people of color in psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy: A review of the literature. BMC Psychiatry 2018, 18, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Campbell, M.; Williams, M.T. The Ethic of Access: An AIDS Activist Won Public Access to Experimental Therapies, and This Must Now Extend to Psychedelics for Mental Illness. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 680626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stauffer, C.S.; Brown, M.R.; Adams, D.; Cassity, M.; Sevelius, J. MDMA-assisted psychotherapy; Inclusion of transgender and gender diverse people in the frontiers of PTSD treatment trials. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 932605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MAPS Public Benefit Corporation. MAPS PBC Completes Second Phase 3 “MAPP2” Trial of MDMA-Assisted Therapy for Treatment of PTSD. 2022. Available online: https://mapspublicbenefit.com/press-releases/mapp2-completion-announcement/ (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Brennan, W.; Jackson, M.A.; MacLean, K.; Ponterotto, J.G. A Qualitative Exploration of Relational Ethical Challenges and Practices in Psychedelic Healing. J. Humanist. Psychol. 2021, 65, 00221678211045265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Letheby, C. The epistemic innocence of psychedelic states. Conscious. Cogn. 2016, 39, 28–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMillan, R.M. Prescribing meaning: Hedonistic perspectives on the therapeutic use of psychedelic-assisted meaning enhancement. J. Med. Ethics 2020, 47, 701–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, A.; Tagliazucchi, E.; Weijer, C. The ethics of psychedelic research in disorders of consciousness. Neurosci. Conscious. 2019, 2019, niz013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eleftheriou, M.E.; Thomas, E. Examining the Potential Synergistic Effects between Mindfulness Training and Psychedelic-Assisted Therapy. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 707057. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Romeu, A.; Richards, W.A. Current perspectives on psychedelic therapy: Use of serotonergic hallucinogens in clinical interventions. Int. Rev. Psychiatry 2018, 30, 291–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.; Richards, W.; Johnson, M.; McCann, U.; Jesse, R. Mystical-type experiences occasioned by psilocybin mediate the attribution of personal meaning and spiritual significance 14 months later. J. Psychopharmacol. 2008, 22, 621–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, R.R.; Richards, W.A.; McCann, U.; Jesse, R. Psilocybin can occasion mystical-type experiences having substantial and sustained personal meaning and spiritual significance. Psychopharmacol. 2006, 187, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Griffiths, R.R.; Johnson, M.W.; Richards, W.A.; Richards, B.D.; Jesse, R.; MacLean, K.A.; Barrett, F.S.; Cosimano, M.P.; Klinedinst, M.A. Psilocybin-occasioned mystical-type experience in combination with meditation and other spiritual practices produces enduring positive changes in psychological functioning and in trait measures of prosocial attitudes and behaviors. J. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 32, 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- MacLean, K.A.; Johnson, M.W.; Griffiths, R.R. Mystical experiences occasioned by the hallucinogen psilocybin lead to increases in the personality domain of openness. J. Psychopharmacol. 2011, 25, 1453–1461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Preller, K.H.; Herdener, M.; Pokorny, T.; Planzer, A.; Kraehenmann, R.; Stämpfli, P.; Liechti, M.E.; Seifritz, E.; Vollenweider, F.X. The Fabric of Meaning and Subjective Effects in LSD-Induced States Depend on Serotonin 2A Receptor Activation. Curr. Biol. 2017, 27, 451–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Erritzoe, D.; Roseman, L.; Nour, M.M.; MacLean, K.; Kaelen, M.; Nutt, D.J.; Carhart-Harris, R.L. Effects of psilocybin therapy on personality structure. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2018, 138, 368–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lebedev, A.V.; Lövdén, M.; Rosenthal, G.; Feilding, A.; Nutt, D.J.; Carhart-Harris, R.L. Finding the self by losing the self: Neural correlates of ego-dissolution under psilocybin. Hum. Brain Mapp. 2015, 36, 3137–3153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.R.; Sisti, D. Ethics and ego dissolution: The case of psilocybin. J. Med. Ethics 2020, 47, 807–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schleim, S. Grounded in Biology: Why the Context-Dependency of Psychedelic Drug Effects Means Opportunities, Not Problems for Anthropology and Pharmacology. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 906487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Askew, R.; Williams, L. Rethinking enhancement substance use: A critical discourse studies approach. Int. J. Drug Policy 2021, 95, 102994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupuis, D. Psychedelics as Tools for Belief Transmission. Set, Setting, Suggestibility, and Persuasion in the Ritual Use of Hallucinogens. Front. Psychol. 2021, 12, 730031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaelen, M.; Roseman, L.; Kahan, J.; Santos-Ribeiro, A.; Orban, C.; Lorenz, R.; Barrett, F.S.; Bolstridge, M.; Williams, T.; Williams, L.; et al. LSD modulates music-induced imagery via changes in parahippocampal connectivity. Eur. Neuropsychopharmacol. J. Eur. Coll. Neuropsychopharmacol. 2016, 26, 1099–1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- dos Santos, R.G.; Bouso, J.C.; Alcázar-Córcoles, M.; Hallak, J.E.C. Efficacy, tolerability, and safety of serotonergic psychedelics for the management of mood, anxiety, and substance-use disorders: A systematic review of systematic reviews. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2018, 11, 889–902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rucker, J.J.; Young, A.H. Psilocybin: From Serendipity to Credibility? Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 659044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carroll, K.M. Lost in translation? Moving contingency management and cognitive behavioral therapy into clinical practice. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 2014, 1327, 94–111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, J.R.; Michaels, T.I.; Sevelius, J.; Williams, M.T. The psychedelic renaissance and the limitations of a White-dominant medical framework: A call for indigenous and ethnic minority inclusion. J. Psychedelic Stud. 2019, 4, 4–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aday, J.S.; Bloesch, E.K.; Davoli, C.C. 2019: A year of expansion in psychedelic research, industry, and deregulation. Drug Sci. Policy Law 2020, 6, 2050324520974484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hausfeld, R. Will MDMA-Assisted Psychotherapy Be Covered by Health Insurance? Psymposia. 2019. Available online: https://www.psymposia.com/magazine/mdma-insurance/ (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Noorani, T. Making psychedelics into medicines: The politics and paradoxes of medicalization. J. Psychedelic Stud. 2019, 4, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- INCB. Narcotic Drug Report 2021; INCB: Vienna, Austria, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Corrigan, K.; Haran, M.; McCandliss, C.; McManus, R.; Cleary, S.; Trant, R.; Kelly, Y.; Ledden, K.; Rush, G.; O’keane, V.; et al. Psychedelic perceptions: Mental health service user attitudes to psilocybin therapy. Ir. J. Med. Sci. 2021, 191, 1385–1397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levin, A.; Nagib, P.B.; Deiparine, S.; Gao, T.; Mitchell, J.; Davis, A.K. Inconsistencies between national drug policy and professional beliefs about psychoactive drugs among psychiatrists in the United States. Int. J. Drug Policy 2022, 108, 103816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Page, L.A.; Rehman, A.; Syed, H.; Forcer, K.; Campbell, G. The Readiness of Psychiatrists to Implement Psychedelic-Assisted Psychotherapy. Front. Psychiatry 2021, 12, 743599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, W.R.; Appelbaum, P.S. Two Models of Legalization of Psychedelic Substances: Reasons for Concern. JAMA 2021, 326, 697–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Greenwald, G. Drug Decriminalization in Portugal: Lessons for Creating Fair and Successful Drug Policies. CATO Institute Washington, DC. 2009. Available online: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=1464837 (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Gonçalves-Pinho, M.; Bragança, M.; Freitas, A. Psychotic disorders hospitalizations associated with cannabis abuse or dependence: A nationwide big data analysis. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2019, 29, e1813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Government of Canada. Special Access Programme—Drugs. 2022. Available online: https://www.canada.ca/en/health-canada/services/drugs-health-products/special-access/drugs/special-access-programme-drugs.html (accessed on 11 November 2022).

- Mocanu, V.; Mackay, L.; Christie, D.; Argento, E. Safety considerations in the evolving legal landscape of psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. Subst. Abus. Treat. Prev. Policy 2022, 17, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cusimano, J. A pilot psychedelic psychopharmacology elective. Curr. Pharm. Teach. Learn. 2022, 14, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Amsterdam, J.; Peters, G.-J.Y.; Pennings, E.; Blickman, T.; Hollemans, K.; Breeksema, J.J.J.; Ramaekers, J.G.; Maris, C.; van Bakkum, F.; Nabben, T.; et al. Developing a new national MDMA policy: Results of a multi-decision multi-criterion decision analysis. J. Psychopharmacol. 2021, 35, 537–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hauskeller, C.; Artinian, T.; Fiske, A.; Marin, E.S.; Romero, O.S.G.; Luna, L.E.; Crickmore, J.; Sjöstedt-Hughes, P. Decolonization is a metaphor towards a different ethic. The case from psychedelic studies. Interdiscip. Sci. Rev 2022, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feinberg, B. Undiscovering the Pueblo Mágico: Lessons from Huautla for the Psychedelic Renaissance. In Plant Medicines, Healing and Psychedelic Science: Cultural Perspectives; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2018; pp. 37–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lutkajtis, A. Lost Saints: Desacralization, Spiritual Abuse and Magic Mushrooms. Fieldwork Relig. 2020, 14, 118–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyons, T.; Carhart-Harris, R.L. Increased nature relatedness and decreased authoritarian political views after psilocybin for treatment-resistant depression. J. Psychopharmacol. 2018, 32, 811–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nour, M.M.; Evans, L.; Carhart-Harris, R.L. Psychedelics, Personality and Political Perspectives. J. Psychoact. Drugs 2017, 49, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žuljević, M.F.; Buljan, I.; Leskur, M.; Kaliterna, M.; Hren, D.; Duplančić, D. Validation of a new instrument for assessing attitudes on psychedelics in the general population. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 18225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Natural Origin | |

|---|---|

| LSD (lysergic acid diethylamide) | Ergot fungi |

| Psilocybin | Psilocybe spp. mushrooms |

| Mescaline | Peyote; San Pedro Cactus |

| DMT (N,N-dimethyltryptamine) | Ayahuasca (mixture of many plants) |

| Depressive Disorders | Anxiety Disorders | Substance Use Disorder | Other Disorders | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LSD | __________ | Anxiety AALTD | Opioid Use Disorder Alcohol Use Disorder | Cluster Headache |

| Psilocybin | DRLTC MDD TRD a | ARLTC | Nicotine Use Disorder Alcohol Use Disorder | Eating Disorders |

| DMT | TRD | __________ | __________ | __________ |

| Ketamine | MDD | __________ | Opioid Use Disorder Alcohol Use Disorder b | __________ |

| MDMA | __________ | __________ | Alcohol Use Disorder | PTSD c |

| Inclusion Criteria |

|---|

| 1. Original peer-reviewed studies, theses/dissertations, reviews, follow-up studies, commentaries, opinion pieces, conference abstracts, study protocols of clinical trials |

| 2. Study designs including quantitative, qualitative, mixed-methods, case reports, case series |

| 3. Eligible psychedelic compounds: psilocybin, LSD, MDMA, ketamine, and ayahuasca |

| 4. Discussion of ethical, legal, and clinical themes |

| Main Author, Year | Country | Study Design | Purpose of Study |

|---|---|---|---|

| (Miceli McMillan, 2022) | Australia | Essay | Cultural impact on and injustice towards Indigenous communities due to the scientific use of psychedelics. |

| (Cusimano, 2022) | USA | Research Article | Discussion with students about problems and solutions related to psychedelic therapy. |

| (Greif and Šurkala, 2020) | Slovak Republic | Perspective | Initial experiments and reflection about psychedelics’ real therapeutic effect. |

| (Plesa and Petranker, 2022) | Canada | Research Article | Neo-liberalism and the risks of psychedelics in the self-help industry. |

| (Rucker and Young, 2021) | United Kingdom | Perspective | Discussion of the acceleration of studies on psychedelics and their risks. |

| (Johnson, 2021) | USA | Opinion | Beliefs and religion during therapy and the therapist’s own beliefs. |

| (Bodnár and Kakuk, 2019) | Hungary | Review | Ethics of clinical research with LSD using the 7 dimensions of E. J. Emanuel. |

| (Miceli McMillan, 2020) | Australia | Essay | Hedonistic concepts used in psychedelic therapy. |

| (Langlitz et al., 2021) | USA, Canada, Switzerland, Germany | Perspective | Whether psychedelics can help users connect with their ideals and support moral–political ideas. |

| (Smith and Appelbaum, 2022) | USA | Review | Recommendations for solutions to novel problems concerning psychedelics. |

| (Letheby, 2022) | Australia, Canada | Review | The establishment of emerging lines of research at the intersection of philosophy and psychedelic science. |

| (Hauskeller et al., 2022) | United Kingdom | Research Article | The study of psychedelics with dualistic concepts used in colonial and decolonial thought. |

| (Stauffer et al., 2022) | USA | Research Article | The participation of transgender and gender-diverse people in PTSD research and assessment for their openness to MDMA-assisted psychotherapy. |

| (Miceli McMillan, 2021) | Australia | Research Article | A bioethical reflection about re-medicalization of psychedelics. |

| (Mintz et al., 2022) | USA, United Kingdom | Perspective | Encouragement for further research and debate to make psychedelic research and therapies accessible to members of disability communities. |

| (Kious et al., 2022) | USA | Perspective | If psychedelics can affect investigators’ enthusiasm, raising concerns about bias and scientific integrity. |

| (Petranker et al., 2020) | Canada | Perspective | The importance of open science on psychedelic research. |

| (Pilecki et al., 2021) | USA | Opinion | How therapists can mitigate risks and practice within legal and ethical boundaries when incorporating psychedelics into traditional psychotherapy. |

| (van Amsterdam et al., 2021) | The Netherlands | Research Article | Hypothetical Dutch reform legislation to create a rational MDMA policy. |

| (Schleim, 2022) | The Netherlands | Opinion | Discussion on context-dependency of placebo effects and moral psychopharmacology. |

| (Williams et al., 2021) | Australia | Perspective | Discussion of potential psychedelic obstacles to community clinics among a group of clinicians and researchers. |

| (Page, L.A. et al., 2021) | United Kingdom | Brief Report | The attitudes and knowledge of NHS psychiatrists on psychedelic-assisted psychotherapy. |

| (Marcus, 2022) | USA | Research Article | Ethical tensions between curanderos, mental health practitioners, and ayahuasca retreat centers. |

| (Gerber et al., 2021) | Brazil, Mexico, Switzerland, USA | Opinion | How Indigenous communities are currently unable to claim their rights to traditional medicines, despite international treaties. |

| (Mocanu et al., 2022) | Canada | Essay | A demonstration that expanding access to psychedelics requires consideration of a range of factors. |

| (Askew and Williams, 2021) | United Kingdom | Research Article | Critical discourse examining how substances can be used for self-improvement. |

| (Thal et al., 2021) | Australia, Germany | Review | A description of the current conditions and theoretical knowledge for substance-assisted psychotherapy, including ethics and spiritual emphasis, methods, models, and concepts of psychological mechanisms of action. |

| (Yaden et al., 2022) | USA | Opinion | How psychedelic research should focus on integrating medications into the standard of care rather than recreating ethical and socio-political problems. |

| (Campbell and Williams, 2021) | USA, Canada | Perspective | A discussion of whether psychiatry should allow patients’ preferences to guide policy and law regarding psychedelics. |

| (Smith and Appelbaum, 2021) | USA | Opinion | A discussion about Oregon and California’s different approaches to legalization, with cautionary precedents. |

| (Mathai et al., 2022) | USA | Research Article | Informed consent processes for ketamine therapy clinicians to identify the potential for growth. |

| (Žuljević et al., 2022) | Croatia | Research Article | Psychometric properties of the Attitudes on Psychedelics Questionnaire in a sample of the Croatian general population. |

| (Peterson et al., 2019) | USA, Argentina, Canada | Opinion | Ethical analysis of psychedelic research involving consciousness patients. |

| (Levin et al., 2022) | USA | Research Article | Examining whether psychiatrists’ perceptions of four psychoactive drugs differ from schedules. |

| (Corrigan et al., 2022) | Ireland | Research Article | Analyzing mental health service users’ attitudes to psychedelics and psilocybin therapy. |

| (Michaels et al., 2018) | USA | Review | Examining ethno-racial differences in inclusion and recruitment of people of color in psychedelic clinical trials. |

| (Phelps, 2017) | USA | Research Article | To review and compile psychedelic therapist competencies derived from the psychedelic literature. |

| (Smith and Sisti, 2021) | USA | Research Article | To show that psychedelics pose novel risks and require enhanced informed consent, leading to ethical considerations as they move into mainstream clinical psychiatry. |

| (Brennan et al., 2021) | USA | Research Article | An interview with 23 psychedelic clinicians about nonsexual touch, sexual boundary-setting, and experiences while navigating multiple relationships in their work. |

| (Dupuis, 2021) | France | Research Article | An argument on how hyper suggestibility is the main factor in making psychedelics powerful for belief transmission, producing doubt, ambivalence, and reflexivity. |

| (Eleftheriou and Thomas, 2021) | United Kingdom | Review | An explanation of how mindfulness-based interventions and psychedelic therapy have been found to have synergistic effects, but replication is needed to fully understand the effects of set and setting. |

| (Kuypers et al., 2019) | The Netherlands, United Kingdom, Denmark, USA, Italy | Opinion | To answer questions and provide guidelines for research on microdosing. |

| Should be obtained from every patient undergoing psychedelic therapy, regardless of prior experience with psychedelics [36]. |

| Should clarify the realistic expectations of the intervention, distinguishing them from media-generated unrealistic expectations. IC should also cover evidence-based effects for each medical situation [33]. |

| Must encompass all types of decision-making following psychedelic intake, including physical boundaries between patient and therapist, the risk of self-harm, violent events, and property destruction [31,34,37,38,39]. |

| Needs to include potential long-term side effects [31], which might include changes in moral, philosophical, political, and religious beliefs that can result from psychedelic therapy [30,38,39]. |

| Should account for potential cultural differences between the patient and therapist to avoid misunderstandings during the therapy session [30,34]. |

| Should include provisions for the patient’s decision to leave the session during the altered hallucinogenic state, allowing researchers and clinicians to respect the patient’s autonomy [36]. |

| Could include surrogate decision-making in case of changes that make the patient unable to decide under psychedelic effects [36]. |

| Should be tailored for patients with physical and mental impairments, considering the involvement of caregivers as decision-makers [40]. |

| Clinical Consideration | Description |

|---|---|

| Need for Evidence and Training [48,54,81] | Prioritize evidence of efficacy, effectivity, and the training of mental health professionals in psychedelic therapy. |

| Avoid hasty preparation of therapists to prevent harm and ensure safe settings. | |

| Provide diverse training to therapists and prescribers accredited by national and regulated entities. | |

| Importance of Setting [40,54] | Create a calm, natural-like, and personalized setting in psychedelic therapy. |

| Enhance therapeutic effects and reduce adverse events through an appropriate setting. | |

| Ensure inclusivity for individuals with physical disabilities, enabling equal access to treatment. | |

| Accessibility and Affordability [33,54,82,83,84] | Address questions of accessibility, overall price, and co-payment in psychedelic therapy. |

| Consider the limited resources of patients impacted by their symptoms. | |

| Ensure equitable access to treatment, particularly for individuals with chronic psychiatric disorders, amid concerns about a for-profit industry. | |

| Real-Life Practice vs. Research [54,85] | Recognize potential differences between research conducted in artificial settings and real-life clinical practice. |

| Overcome challenges in patient selection, misdiagnosis, exclusion of at-risk individuals, and off-label use of psychedelics in clinical practice. | |

| Conduct controlled and comprehensive evaluations of diagnosis by clinicians before implementing psychedelic interventions to ensure patient safety and treatment benefits. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Azevedo, N.; Oliveira Da Silva, M.; Madeira, L. Ethics of Psychedelic Use in Psychiatry and Beyond—Drawing upon Legal, Social and Clinical Challenges. Philosophies 2023, 8, 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies8050076

Azevedo N, Oliveira Da Silva M, Madeira L. Ethics of Psychedelic Use in Psychiatry and Beyond—Drawing upon Legal, Social and Clinical Challenges. Philosophies. 2023; 8(5):76. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies8050076

Chicago/Turabian StyleAzevedo, Nuno, Miguel Oliveira Da Silva, and Luís Madeira. 2023. "Ethics of Psychedelic Use in Psychiatry and Beyond—Drawing upon Legal, Social and Clinical Challenges" Philosophies 8, no. 5: 76. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies8050076