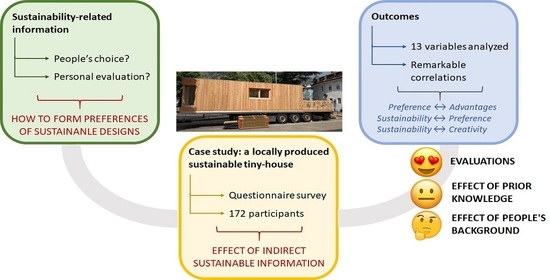

How Sustainability-Related Information Affects the Evaluation of Designs: A Case Study of a Locally Manufactured Mobile Tiny House

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Forms of Sustainable Information and Other Factors Affecting Preference and Choice of Products

2.2. Perception and Evaluation in the Field of Constructions and the Built Environment

- The considered source.

- How participants have interacted with the designs so as to compare the case studies with real-world situations and to infer how they could shape their evaluation.

- The methods used to extract perception and evaluation data.

- The size of the sample and characteristics of participants.

- Additional critical information about the way the studies have been conducted and other relevant data, markedly about knowledge, collective and individual aspects.

| Source | Representation and Interaction Mode | Investigation Method | Participants’ Sample | Research Protocol and Relevant Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [40] | Real user experience collected in traditional and modern buildings in Cameroon | Questionnaire | 1750 questionnaires were answered depending on the residents’ geographical area | - the participants were aware of the characteristics of the residential area - data about socio-demographic questions and residential experience was collected |

| [41] | Rendering and 3D models of a future neighborhood redevelopment project | Questionnaire | 269 respondents selected in a specific neighborhood | - the participants were not aware of the characteristics of the future buildings - data about socio-demographic questions and residential experience was collected - preferences evaluation was based on an 11-point rating scale |

| [42] | Rendering and picture of a post-industrial landscape renovation | Questionnaire | 450 residents randomly selected | - the participants were aware of the characteristics of the residential area - data about socio-demographic questions and residential experience was collected |

| [34] | Experiences with green buildings | Online survey | 342 residents (valid answers) | - the participants reported an experience a posteriori; no evaluation of a new design - data about background and some demographic factors were collected |

| [43] | Real-world experiments at the Department of Civil Engineering of the University of Aveiro, Portugal. | Questionnaire | 150 random users among students, researchers, professors, and administrative staff | - direct questionnaires were administered with enquiries about water consumption behaviour and preferences - the participants were not aware of the characteristics of sustainable water consumption behaviours - no socio-demographic or background questions were asked |

| [44] | User experience of life in a temporary house | Questionnaire and interviews | 32 families interviewed and 181 questionnaires collected | - the participants were aware of the characteristics of the buildings; - no socio-demographic or background analysis was performed - interview and questionnaire made to understand the importance of the space and the sustainability of the used material |

| [45] | Rendering and pictures of 32 scenario of built environment design | Questionnaire | 752 respondents divided into three different groups of target population that included building users/building owners, road users | - the participants were not aware of the characteristics of the buildings - socio-demographic and background information was collected |

| [46] | Two real buildings for demonstration scopes | Interviews | 61 participants with different degrees of experience | - the participants were aware of the characteristics of the buildings - 32 in-depth, semi-structured interviews with building professionals were conducted - 29 shorter interviews with building users were conducted |

| [47] | Pictures of six selected urban streets in the city of Seoul | Interviews | Six experts in public space, transportation, and behaviour | - the participants were not aware of the characteristics of the urban streets - no socio-demographic or background analysis was performed - sustainability, amenity, placeness and accessibility of the urban streets based on open questions were evaluated |

| [48] | Five scenarios (electricity production; vegetable; green roof implementation and rainwater harvesting) of future development of a residential area in Barcelona | Questionnaire | 60 respondents selected among residents, experts and public institutions | - the participants were not aware of the characteristics of the residential area - no socio-demographic or background questions were asked - respondents used a 5-point ranking of the scenario considering sustainability, environmental, economic and social indicators |

| [49] | Rendering and pictures of 160 wood constructions | Questionnaire | 159 respondents selected among wood construction users | - the participants were aware of the characteristics of the building - background and demographic questions were asked - open questions were added - sustainability and economic criteria were evaluated |

2.3. Literature Gap and Objectives

- Most of the designs were evaluated by experts or people with a significant awareness of the contextual factors related to buildings and urban spaces. The evaluation of ordinary people is rarely dealt with, while their views are critical when it comes to preferences, choices and purchases.

- In a few cases, real-world situations were studied; among them, very peculiar aspects were focused upon, see [43]. Conversely, the experience found with designs, especially if they present innovative features, is much more reliable if actual artefacts are involved [50]. In the case of green buildings or sustainable-oriented architectural interventions, it is assumed that new characteristics are included to fulfil the requirements of increased sustainability.

- The knowledge of the presented designs is dissimilar across participants of different studies but poorly considered as a factor affecting evaluation and acceptance in those contributions with participants having different degrees of awareness.

- A large number of studies consider demographic and background data, which have proven critical to evaluations.

- The use of a real building or realistic prototype even though this may be inconvenient because of the size of artefacts in the construction industry.

- The involvement of ordinary people.

- The consideration of people’s knowledge and its effect on evaluations and perception, where information is provided in an indirect way, which is more realistic in a real-case scenario.

- The consideration of people’s background and demographic data, along with their effect on evaluations and perception.

- Ordinary people’s overall perception and evaluation of a real green building;

- To what extent the (perceived) knowledge of the properties of a sustainable building affects evaluation and perceived sustainability, which contribute to product desirability and choice as shown above;

- The effect of background and demographic data on perception and evaluation;

- The interplay between multiple evaluation criteria to get more insight into the evaluation phenomenon.

3. Methodology and Context of the Study

3.1. Research Design

3.2. Product and Characteristics Thereof

3.3. Relevant Information about the Project

3.4. Participants and Relevant Aspects of the Experimental Procedure

- Specific information about product peculiarities would have been given only after the visit unless this was explicitly requested to the experimenters before or during the visit; as well, paper-based or online informative material about the project and the Tiny FOP MOB was given to participants based on their requests.

- A scheduled timetable was not planned by providing participants with the chance to observe the prototype as long as they wanted and needed. If the Tiny FOP MOB was free at the time of recruitment, the visit could take place immediately.

- A limitation on the number of simultaneous visitors was imposed, together with the rule of wearing a mask inside the Tiny FOP MOB, due to the COVID-19 pandemic situation at the time of the experiments.

- Gender;

- Age range (options: 18–30, 31–40, 41–50, 51–60, 61–70, 71+);

- Origin, markedly if the participant lived in a South Tyrolean municipality;

- Education (options: primary school, secondary school, high school, second-level vocational school, University degree, Ph.D.);

- Job.

- 63 men and 79 women;

- 39 people aged 18–30; 24 people aged 31–40; 22 people aged 41–50; 38 people aged 51–60; 9 people aged 61–70; 8 people aged 71 or older;

- 84 South Tyroleans and 59 people whose residency was outside South Tyrol;

- 2 people with primary school; 10 people with secondary school; 44 people with high school; 17 people with vocational school; 54 people with an University degree; 15 people with a Ph.D. degree;

- 14 people working as architects, engineers, urban planners, entrepreneurs or managers in the building or wood industry, who could be considered experts in the field; 129 non-experts.

3.5. Questionnaires and Extracted Variables

4. Results

4.1. Objective 1: Overall Perception and Evaluation of a Green Building

4.2. Objective 2: Effect of the Perceived Knowledge on the Evaluation of the Prototype

4.3. Objective 3: Effect of Background and Demographic Data on the Evaluation of the Prototype

4.4. Objective 4: Interplay among Evaluation Criteria

5. Discussions

5.1. Objective 1: Overall Perception and Evaluation of a Green Building

5.2. Objective 2: Effect of the Perceived Knowledge on the Evaluation of the Prototype

- The aforementioned peculiar contextual factors, such as unevenness of information given to participants, knowledge possibly coming from different sources and in different modalities, etc., are candidates to explain the divergence of the presented results from previous work.

- While all the analysed answers are inherently subjective, this might particularly apply to knowledge, as each participant could have evaluated differently the amount of information processed and the lack of necessary knowledge to assess the prototype in a fully aware manner. In other words, the impossibility of verifying the metrics used by participants to provide [Knowledge] values represents an important limitation of the paper, besides being a difference with respect to most previous literature.

- An additional hypothesis is that a tiny house, clearly built with natural materials, might be considered per se a sustainable product; hence, details about the project, such as the planned use of the Tiny FOP MOB for an RwL or the origin of materials, could have poorly oriented evaluations. In other terms and with a closer look at the design research, the product considered could lend itself to effective indirect communication of sustainable aspects.

5.3. Objective 3: Effect of Background and Demographic Data on the Evaluation of the Prototype

5.4. Objective 4: Interplay among Evaluation Criteria

6. Conclusions

- The tiny house received consistently positive evaluations concerning its perceived quality, creativity, appropriateness and sustainability. The majority of evaluators were randomly selected volunteers with a limited number of experts in the field. As such, the involved sample could be considered as well representative of a group of ordinary people despite the participants’ likely intrinsic interest towards the product and their probable sustainable attitude.

- Prior knowledge about the tiny house and the project within which it was designed, developed and built played no evident role in the evaluations.

- People’s background did not affect evaluations significantly either. In contrast, some evaluation variables were affected by gender and age, where women and younger people overall rated the tiny house better in terms of sustainability and other factors.

- The chosen evaluation criteria were shown to be significantly correlated with a remarkable association between perceived sustainability vs. preference and creativity.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- She, J.; MacDonald, E.F. Exploring the Effects of a Product’s Sustainability Triggers on Pro-Environmental Decision-Making. J. Mech. Des. 2017, 140, 011102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacDonald, E.; Whitefoot, K.; Allison, J.T.; Papalambros, P.Y.; Gonzalez, R. An Investigation of Sustainability, Preference, and Profitability in Design Optimization. In Proceedings of the ASME 2010 International Design Engineering Technical Conferences and Computers and Information in Engineering Conference, Montreal, QC, Canada, 15–18 August 2010; pp. 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goucher-Lambert, K.; Cagan, J. The Impact of Sustainability on Consumer Preference Judgments of Product Attributes. J. Mech. Des. 2015, 137, 081401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balikci, A.; Borgianni, Y.; Maccioni, L.; Nezzi, C. A Framework of Unsustainable Behaviors to Support Product Eco-Design. Sustainability 2021, 13, 11394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mandel, N.; Johnson, E. When Web Pages Influence Choice: Effects of Visual Primes on Experts and Novices. J. Consum. Res. 2002, 29, 235–245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- She, J.; MacDonald, E. Priming Designers to Communicate Sustainability. J. Mech. Des. 2013, 136, 011001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- MacDonald, E.F.; She, J. Seven cognitive concepts for successful eco-design. J. Clean. Prod. 2015, 92, 23–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turunen, L.L.M.; Halme, M. Communicating actionable sustainability information to consumers: The Shades of Green instrument for fashion. J. Clean. Prod. 2021, 297, 126605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leire, C.; Thidell, A. Product-related environmental information to guide consumer purchases—A review and analysis of research on perceptions, understanding and use among Nordic consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2005, 13, 1061–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maccioni, L.; Borgianni, Y.; Basso, D. Value Perception of Green Products: An Exploratory Study Combining Conscious Answers and Unconscious Behavioral Aspects. Sustainability 2019, 11, 1226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Shao, J.; Li, W.; Aneye, C.; Fang, W. Facilitating mechanism of green products purchasing with a premium price—Moderating by sustainability-related information. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2021, 29, 686–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiu, M.-C.; Tu, Y.-L.; Kao, M.-C. Applying deep learning image recognition technology to promote environmentally sustainable behavior. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2022, 31, 736–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.-N. Different Shades of Green Consciousness: The Interplay of Sustainability Labeling and Environmental Impact on Product Evaluations. J. Bus. Ethics 2014, 128, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stöckigt, G.; Schiebener, J.; Brand, M. Providing sustainability information in shopping situations contributes to sustainable decision making: An empirical study with choice-based conjoint analyses. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2018, 43, 188–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goucher-Lambert, K.; Moss, J.; Cagan, J. Inside the Mind: Using Neuroimaging to Understand Moral Product Preference Judgments Involving Sustainability. J. Mech. Des. 2017, 139, 041103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cho, Y.-N.; Soster, R.L.; Burton, S. Enhancing Environmentally Conscious Consumption through Standardized Sustainability Information. J. Consum. Aff. 2017, 52, 393–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Shen, M.; Chu, M. Why is green consumption easier said than done? Exploring the green consumption attitude-intention gap in China with behavioral reasoning theory. Clean. Responsible Consum. 2021, 2, 100015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodhouse, A.; Davis, J.; Pénicaud, C.; Östergren, K. Sustainability checklist in support of the design of food processing. Sustain. Prod. Consum. 2018, 16, 110–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghupathi, D.; Yannou, B.; Farel, R.; Poirson, E. Customer sentiment appraisal from user-generated product reviews: A domain independent heuristic algorithm. Int. J. Interact. Des. Manuf. 2015, 9, 201–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Lim, Y.; Chang, P.; Guo, Y.; Zhang, M.; Wang, X.; Yu, X.; Lehto, M.R.; Cai, H. Ecolabel’s role in informing sustainable consumption: A naturalistic decision making study using eye tracking glasses. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 218, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iraldo, F.; Griesshammer, R.; Kahlenborn, W. The future of ecolabels. Int. J. Life Cycle Assess. 2020, 25, 833–839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chekima, B.; Wafa, S.A.W.S.K.; Igau, O.A.; Chekima, S.; Sondoh, S.L., Jr. Examining green consumerism motivational drivers: Does premium price and demographics matter to green purchasing? J. Clean. Prod. 2016, 112, 3436–3450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Andrade Silva, A.R.; Bioto, A.S.; Efraim, P.; de Castilho Queiroz, G. Impact of sustainability labeling in the perception of sensory quality and purchase intention of chocolate consumers. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 141, 11–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Souza, C.; Taghian, M.; Lamb, P. An empirical study on the influence of environmental labels on consumers. Corp. Commun. Int. J. 2006, 11, 162–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pérez-Belis, V.; Agost, M.J.; Vergara, M. Consumers’ visual attention and emotional perception of sustainable product information: Case study of furniture. In Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Kansei Engineering and Emotion Research 2018, Kuching, Malaysia, 19–22 March 2018; Springer: Singapore, 2018; pp. 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franz-Balsen, A.; Heinrichs, H. Managing sustainability communication on campus: Experiences from Lüneburg. Int. J. Sustain. High. Educ. 2007, 8, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saber, M.; Weber, A. How do supermarkets and discounters communicate about sustainability? A comparative analysis of sustainability reports and in-store communication. Int. J. Retail Distrib. Manag. 2019, 47, 1181–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sauer, J.; Sonderegger, A.; Álvarez, M.A.H. The influence of cultural background of test participants and test facilitators in online product evaluation. Int. J. Human-Comput. Stud. 2018, 111, 92–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, C.-L.; Chen, S.-J.; Hsiao, W.-H.; Lin, R. Cultural ergonomics in interactional and experiential design: Conceptual framework and case study of the Taiwanese twin cup. Appl. Ergon. 2016, 52, 242–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carbon, C.C. Psychology of design. Des. Sci. 2019, 5, E26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Park, S.J.; Choi, S.; Kim, E.J. The relationships between socio-demographic variables and concerns about environmental sustainability. Corp. Soc. Responsib. Environ. Manag. 2012, 19, 343–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edinger-Schons, L.M.; Sipilä, J.; Sen, S.; Mende, G.; Wieseke, J. Are Two Reasons Better Than One? The Role of Appeal Type in Consumer Responses to Sustainable Products. J. Consum. Psychol. 2018, 28, 644–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, C.-H. Conducting qualitative and quantitative analyses of sustainable behaviour. J. Retail. Consum. Serv. 2021, 60, 102474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Y.; Hong, Z.; Zhu, J.; Yan, J.; Qi, J.; Liu, P. Promoting green residential buildings: Residents’ environmental attitude, subjective knowledge, and social trust matter. Energy Policy 2018, 112, 152–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blanco, C.F.; Sarasa, R.G.; Sanclemente, C.O. Effects of visual and textual information in online product presentations: Looking for the best combination in website design. Eur. J. Inf. Syst. 2010, 19, 668–686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pettersson, I. Travelling from fascination to new meanings: Understanding user expectations through a case study of autonomous cars. Int. J. Des. 2017, 11, 11. [Google Scholar]

- Becattini, N.; Borgianni, Y.; Cascini, G.; Rotini, F. Investigating users’ reactions to surprising products. Des. Stud. 2020, 69, 100946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puska, P. Does Organic Food Consumption Signal Prosociality? An Application of Schwartz’s Value Theory. J. Food Prod. Mark. 2018, 25, 207–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zins, C. Conceptual approaches for defining data, information, and knowledge. J. Am. Soc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2007, 58, 479–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nematchoua, M.K.; Tchinda, R.; Orosa, J.A. Thermal comfort and energy consumption in modern versus traditional buildings in Cameroon: A questionnaire-based statistical study. Appl. Energy 2014, 114, 687–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verso, V.R.M.L.; Fregonara, E.; Caffaro, F.; Morisano, C.; Peiretti, G.M. Daylighting as the Driving Force of the Design Process: From the Results of a Survey to the Implementation into an Advanced Daylighting Project. J. Daylighting 2014, 1, 36–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Loures, L.; Panagopoulos, T.; Burley, J.B. Assessing user preferences on post-industrial redevelopment. Environ. Plan. B Plan. Des. 2015, 43, 871–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meireles, I.; Sousa, V.; Adeyeye, K.; Silva-Afonso, A. User preferences and water use savings owing to washbasin taps retrofit: A case study of the DECivil building of the University of Aveiro. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2017, 25, 19217–19227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Hosseini, S.A.; Yazdani, R.; de la Fuente, A. Multi-objective interior design optimization method based on sustainability concepts for post-disaster temporary housing units. Build. Environ. 2020, 173, 106742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeel, A.; Notteboom, B.; Yasar, A.; Scheerlinck, K.; Stevens, J. Sustainable Streetscape and Built Environment Designs around BRT Stations: A Stated Choice Experiment Using 3D Visualizations. Sustainability 2021, 13, 6594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blasberg, L.A. Business Models for Smart Sustainability: A Critical Perspective on Smart Homes and Sustainability Transitions. In Business Models for Sustainability Transitions; Palgrave Macmillan: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 273–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seo, M.; Kim, S. A Comparative Evaluation of Utility Value Based on User Preferences for Urban Streets: The Case of Seoul, Korea. Sustainability 2021, 13, 5073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toboso-Chavero, S.; Madrid-López, C.; Durany, X.G.; Villalba, G. Incorporating user preferences in rooftop food-energy-water production through integrated sustainability assessment. Environ. Res. Commun. 2021, 3, 065001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Švajlenka, J.; Kozlovská, M. Perception of the Efficiency and Sustainability of Wooden Building. In Efficient and Sustainable Wood-Based Constructions; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 35–57. [Google Scholar]

- Berni, A.; Borgianni, Y. Making Order in User Experience Research to Support Its Application in Design and Beyond. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 6981. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pregernig, M.; Rhodius, R.; Winkel, G. Design Junctions in Real-World Laboratories: Analyzing Experiences Gained from the Project Knowledge Dialogue Northern Black Forest. GAIA-Ecol. Perspect. Sci. Soc. 2018, 27, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, N.; Lee, S.H.M. Brand identity fit in co-branding: The moderating role of CB identification and consumer coping. Eur. J. Mark. 2014, 48, 1239–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giacalone, D.; Jaeger, S. Better the devil you know? How product familiarity affects usage versatility of foods and beverages. J. Econ. Psychol. 2016, 55, 120–138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Forniés, I.; Sierra-Pérez, J.; Boschmonart-Rives, J.; Gabarrell, X. Metric for measuring the effectiveness of an eco-ideation process. J. Clean. Prod. 2017, 162, 865–874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.; Oh, K. Effects of Perceived Sustainability Level of Sportswear Product on Purchase Intention: Exploring the Roles of Perceived Skepticism and Perceived Brand Reputation. Sustainability 2020, 12, 8650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landis, J.R.; Koch, G.G. An Application of Hierarchical Kappa-type Statistics in the Assessment of Majority Agreement among Multiple Observers. Biometrics 1977, 33, 363–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khamis, H. Measures of association: How to choose? J. Diagn. Med. Sonogr. 2008, 24, 155–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Deuble, M.P.; de Dear, R.J. Green occupants for green buildings: The missing link? Build. Environ. 2012, 56, 21–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M.J.; Oh, M.W.; Kim, J.T. A method for evaluating the performance of green buildings with a focus on user experience. Energy Build. 2013, 66, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Earl, P.E. Lifestyle changes and the lifestyle selection process. J. Bioecon. 2016, 19, 97–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Statement | Variable | Source or Precedent for Using the Variable |

|---|---|---|

| 1. I knew the Tiny FOP MOB and the associated project before the visit. | Knowledge | [10] |

| 2. The Tiny FOP MOB is a good quality product. | Quality | [10] |

| 3. The Tiny FOP MOB represents a product to be preferred over other types and competing products. | Preference | [10] |

| 4. The Tiny FOP MOB has many advantages over other types and competing products. | Advantages | [10] |

| 5. The Tiny FOP MOB has no disadvantages compared to other types or competing products. | Lack of disadvantages | [10] |

| 6. The Tiny FOP MOB is a creative and original product. | Creativity | [10] |

| 7. The Tiny FOP MOB could be a branded product of South Tyrol. | Brand | [52] |

| 8. I would willingly stay in the Tiny FOP MOB for a shorter or longer period of time. | Staying | [53] |

| 9. The Tiny FOP MOB is a suitable building module to live in permanently. | Living | [53] |

| 10. The Tiny FOP MOB is a suitable building module for organising small conferences/seminars. | Seminars | [53] |

| 11. The Tiny FOP MOB is a building module that is suitable as a workplace. | Workplace | [53] |

| 12. The Tiny FOP MOB is a suitable building module to spend the holidays in. | Holidays | [53] |

| 13. The Tiny FOP MOB is a sustainable product. | Sustainability | [54,55] |

| Variable | Totally Disagree (1) | % | Somehow Disagree (2) | % | Indifferent (3) | % | Fairly Agree (4) | % | Totally Agree (5) | % | Median |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Knowledge | 91 | 55.5 | 12 | 7.3 | 30 | 18.3 | 13 | 7.9 | 18 | 11 | 1 |

| 2. Quality | 1 | 0.6 | 2 | 1.9 | 6 | 3.7 | 76 | 46.9 | 77 | 46.1 | 4 |

| 3. Preference | 2 | 1.2 | 5 | 4.3 | 45 | 28 | 68 | 42.2 | 41 | 24.6 | 4 |

| 4. Advantages | 1 | 0.6 | 1 | 0.6 | 50 | 31.3 | 64 | 40 | 44 | 27.5 | 4 |

| 5. Lack of disadvantages | 5 | 3.2 | 11 | 7.1 | 63 | 40.4 | 60 | 38.5 | 17 | 10.9 | 3 |

| 6. Creativity | 2 | 1.2 | 5 | 3 | 8 | 4.8 | 55 | 33.1 | 96 | 57.8 | 5 |

| 7. Brand | 3 | 1.8 | 9 | 5.5 | 27 | 16.6 | 61 | 37.4 | 63 | 38.7 | 4 |

| 8. Staying | 3 | 1.9 | 10 | 6.3 | 31 | 19.4 | 64 | 40 | 52 | 32.5 | 4 |

| 9. Living | 5 | 3 | 14 | 8.4 | 38 | 22.9 | 53 | 31.9 | 56 | 33.7 | 4 |

| 10. Seminars | 4 | 2.4 | 9 | 5.5 | 17 | 10.4 | 70 | 42.7 | 64 | 39 | 4 |

| 11. Workplace | 2 | 1.2 | 5 | 3 | 15 | 9 | 66 | 39.8 | 78 | 47 | 4 |

| 12. Holidays | 1 | 0.6 | 5 | 3.1 | 19 | 11.7 | 49 | 30.1 | 89 | 54.6 | 5 |

| 13. Sustainability | 2 | 1.2 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 1.9 | 36 | 22.2 | 121 | 74.7 | 5 |

| Background Variable | Evaluation Variable | Direction (Increasing) | Strength of Correlation | p-Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | 3 Preference | Woman | 0.228 | 0.011 |

| 6 Creativity | 0.175 | 0.035 | ||

| 7 Brand | 0.237 | 0.008 | ||

| 8 Staying | 0.239 | 0.009 | ||

| 9 Living | 0.244 | 0.007 | ||

| 10 Seminars | 0.280 | 0.001 | ||

| 11 Workplace | 0.221 | 0.011 | ||

| 12 Holidays | 0.263 | 0.002 | ||

| 13 Sustainability | 0.147 | 0.045 | ||

| Age | 5 Lack of disadvantages | Younger | 0.308 | 0.0003 |

| 7 Brand | 0.248 | 0.003 | ||

| 12 Holidays | 0.269 | 0.001 | ||

| 13 Sustainability | 0.237 | 0.005 |

| 2 Quality | 3 Preference | 4 Advantages | 5 Lack of Disadvantages | 6 Creativity | 7 Brand | 8 Staying | 9 Living | 10 Seminars | 11 Workplace | 12 Holidays | 13 Sustainability | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2 Quality | - | |||||||||||

| 3 Preference | 0.516 ** | - | ||||||||||

| 4 Advantages | 0.422 ** | 0.717 ** | - | |||||||||

| 5 Lack of disadvantages | 0.282 ** | 0.478 ** | 0.418 ** | - | ||||||||

| 6 Creativity | 0.310 ** | 0.355 ** | 0.351 ** | 0.357 ** | - | |||||||

| 7 Brand | 0.175 * | 0.383 ** | 0.341 ** | 0.242 ** | 0.406 ** | - | ||||||

| 8 Staying | 0.343 | 0.287 | 0.227 | 0.290 | 0.344 | 0.136 | - | |||||

| 9 Living | 0.233 ** | 0.367 ** | 0.221 ** | 0.319 ** | 0.295 ** | 0.381 ** | 0.497 ** | - | ||||

| 10 Seminars | 0.229 ** | 0.254 ** | 0.152 | 0.154 | 0.351 ** | 0.240 ** | 0.370 ** | 0.444 ** | - | |||

| 11 Workplace | 0.183 * | 0.252 ** | 0.110 | 0.187 * | 0.217 ** | 0.265 ** | 0.366 ** | 0.504 ** | 0.493 ** | - | ||

| 12 Holidays | 0.129 | 0.240 ** | 0.149 | 0.178 * | 0.209 ** | 0.394 ** | 0.416 ** | 0.613 ** | 0.334 ** | 0.350 ** | - | |

| 13 Sustainability | 0.340 ** | 0.414 ** | 0.316 ** | 0.236 ** | 0.475 ** | 0.267 ** | 0.297 ** | 0.305 ** | 0.194 * | 0.304 ** | 0.243 ** | - |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nezzi, C.; Ruiz-Pastor, L.; Altavilla, S.; Berni, A.; Borgianni, Y. How Sustainability-Related Information Affects the Evaluation of Designs: A Case Study of a Locally Manufactured Mobile Tiny House. Designs 2022, 6, 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs6030057

Nezzi C, Ruiz-Pastor L, Altavilla S, Berni A, Borgianni Y. How Sustainability-Related Information Affects the Evaluation of Designs: A Case Study of a Locally Manufactured Mobile Tiny House. Designs. 2022; 6(3):57. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs6030057

Chicago/Turabian StyleNezzi, Chiara, Laura Ruiz-Pastor, Stefania Altavilla, Aurora Berni, and Yuri Borgianni. 2022. "How Sustainability-Related Information Affects the Evaluation of Designs: A Case Study of a Locally Manufactured Mobile Tiny House" Designs 6, no. 3: 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs6030057

APA StyleNezzi, C., Ruiz-Pastor, L., Altavilla, S., Berni, A., & Borgianni, Y. (2022). How Sustainability-Related Information Affects the Evaluation of Designs: A Case Study of a Locally Manufactured Mobile Tiny House. Designs, 6(3), 57. https://doi.org/10.3390/designs6030057