Accessibility in European Peripheral Territories: Analyzing the Portuguese Mainland Connectivity Patterns from 1985 to 2020

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. A Brief Literature Review

3. Materials and Methods

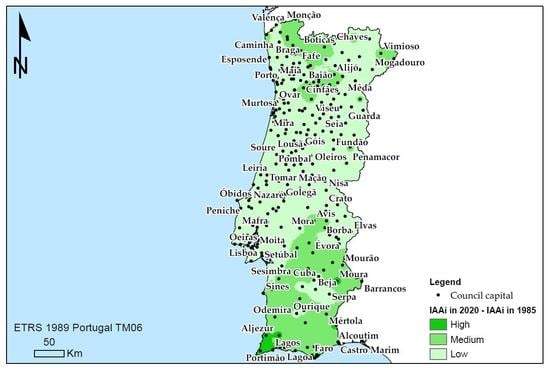

4. Results

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

7. Study Limitations and Future Research Lines

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Gualter, C.; Castanho, R.A.; Pimentel, P.; Carvalho, C.; Sousa, Á.; Graça Batista, M.; Vulevic, A.; Naranjo Gómez, J.M. Transportation and Infrastructures’ Sustainability in Ultra-peripheral Territories: Studies Over the Azores Region. In Trends and Applications in Information Systems and Technologies; Rocha, Á., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanho, R.A.; Naranjo Gómez, J.M.; Vulevic, A.; Behradfar, A.; Couto, G. Assessing Transportation Patterns in the Azores Archipelago. Infrastructures 2021, 6, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanho, R.A.; Behradfar, A.; Vulevic, A.; Naranjo Gómez, J. Analyzing Transportation Sustainability in the Canary Islands Archipelago. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naranjo Gómez, J.; Castanho, R.A.; Cabezas, J.; Loures, L. Assessment of High-Speed Rail Service Coverage in Municipalities of Peninsular Spain. Infrastructures 2020, 5, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bock, B. Rural Marginalisation and the role of Social Innovation: A Turn towards Nexogenous Development and Rural Reconnection. Sociol. Rural. 2016, 56, 552–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ministry of National Development; Vàti Nonprofit Ltd. The Territorial State and Perspectives of the European Union, 2011 Update. Background document for the Territorial Agenda of the European Union 2020. In Proceedings of the Informal Meeting of Ministers Responsible for Spatial Planning and Territorial Development, Gödöllő, Hungary, 19 May 2011; p. 57. [Google Scholar]

- ESPON GEOSPECS. Inner Peripheries: A Socio-Economic Territorial Specificity, Luxembourg [pdf]. 2014. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/GEOSPECS_Final_Report_inner_peripheries_v14.pdf (accessed on 6 April 2016).

- Vulevic, A.; Obradovic, V.; Castanho, R.; Djordjevic, D. Cross-Border Cooperation (CBC) in a Multi-Level Governance System in Southeastern Europe Territories. The Case of ROMANIA—SERBIA Border Space and the Associated Challenges and Obstacles for their Integration. In Proceedings of the 1st Central and Eastern European Planning Conference, Budapest, Romania, 23–24 May 2018; Spaces Crossing Borders, Institute of Geography, Geoeconomy and Sustainable Development, Corvinus University of Budapest: Budapest, Romania, 2018; p. 51, ISBN 978-963-503-701-8. [Google Scholar]

- ESPON. Inner Peripheries in Europe. Possible Development Strategies to Overcome their Marginalising Effects. 2018. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/sites/default/files/attachments/ESPON-Policy-Brief-Inner-Peripheries.pdf (accessed on 19 April 2021).

- Keeble, D.; Owens, P.L.; Thompson, C. Regional accessibility and economic potentialin the European Community. Reg. Stud. 1982, 16, 419–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keeble, D.; Offord, J.; Walker, S. Peripheral Regions in a Community of Twelve Member States; Commission of the European Community: Luxembourg, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Copus, A. From Core-Periphery to Polycentric Development; Concepts of Spatial and A spatial Peripherality. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2001, 9, 539–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, S. Finding a place in the world-economy: Core-periphery relations, the nation-state and the underdevelopment of Garrett County, Maryland. Political Geogr. 1995, 14, 451–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ESPON. Transport Services and Networks: Territorial Trends and Basic Supply of Infrastructure for Territorial Cohesion, Final Report for Espon Project 1.2.1; ESPON: Luxembourg, 2004; Available online: https://www.espon.eu (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- Lucatelli, S.; Carlucci, C.; Guerrizio, M. A strategy for the Inner Areas of Italy. In Proceedings of the European Rural Futures Conference, Asti, Italy, 8 October 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, A.; Silva, J. Cross Border Acessibility and Spatial Development in Portugal and Spain. In Proceedings of the ERSA 2010 Congress, Jonkoping University, Jonkoping, Sweden, 19–23 August 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Vulevic, A.; Castanho, R.A.; Naranjo Gómez, J.M.; Cabezas, J.; Fernández-Pozo, L.; Garrido Velarde, J.; Martín Gallardo, J.; Lousada, S.; Loures, L. Common Regional Development Strategies on Iberian Territories. A Framework for Comprehensive Border Corridors Governance: Establishing Integrated Territorial Development; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vulevic, A.; Castanho, R.A.; Naranjo Gómez, J.M.; Loures, L.; Cabezas, J.; Fernández-Pozo, L.; Martín Gallardo, J. Accessibility Dynamics and Regional Cross-Border Cooperation (CBC) Perspectives in the Portuguese—Spanish Borderland. Sustainability 2020, 12, 1978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vulevic, A.; Obradovic, V.; Castanho, R.A.; Djordjevic, D. Cross-Border Cooperation (CBC) in a Multi-Level Governance System in Southeastern Europe Territories: How to Manage Territorial Governance Processes in Serbia-Romania Border Space. In Cross-Border Cooperation (CBC) Strategies for Sustainable Development; Castanho, R.A., Ed.; IGI Global: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 70–85. ISBN 139781799825135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castanho, R.; Cabezas, J.; Fernández-Pozo, L.; Vulevic, A.; Naranjo Gómez, J.; Martín Gallardo, J.; Loures, L. Common Regional Development Strategies on Iberian Territory. Envisioning New Horizons: Post 2020. In Enfoques en la Planificación Territorial y Urbanística; Thomson Reuters: Navarra, Spain, 2018; pp. 293–303. ISBN 9788491776703. [Google Scholar]

- Vulevic, A.; Macura, D.; Djordjevic, D.; Castanho, R. Assessing Accessibility and Transport Infrastructure Inequities in Administrative Units in Serbia’s Danube Corridor Based on Multi-Criteria Analysis and GIS Mapping Tools. Transylv. Rev. Adm. Sci. 2018, 53, 123–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vulevic, A.; Castanho, R.A.; Gómez-Naranjo, J.; Cabezas, J.; Fernández-Pozo, L. Transport Accessibility to Achieve Sustainable Development. Principles for its Application in CBC Projects: The Euro-City Elvas-Badajoz. In Proceedings of the 16th Congress on Public and Non-profit Marketing (IAPNM), Badajoz, Spain, 4–6 September 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Castanho, R.A.; Vulevic, A.; Cabezas, J.; Fernández-Pozo, L.; Goméz-Naranjo, J.; Loures, L. Accessibility and connectivity—Movement between cities, as a critical factor to achieve success on cross-border cooperation (CBC) projects. A European analysis. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2017, 32, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wegener, M.; Eskelinnen, H.; Fürst, F.; Schürmann, C.; Spiekermann, K. Indicators of Geographical Position. Final Report of the Working Group “Geographical Position” of the Study Programme on European Spatial Planning; IRPUD: Dortmund, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Wegener, M.; Eskelinnen, H.; Fürst, F.; Schürmann, C.; Spiekermann, K. Criteria for the Spatial Differentiation of the EU Territory: Geographical Position; Forschungen 102.2; Bundesamt für Bauwesen und Raumordnung: Bonn, Germany, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lousada, S.; Castanho, R.A. Cooperation Strategies Towards Sustainability in Insular Territories: A Comparison Study Between Porto Santo Island, Madeira Archipelago, Portugal and El Hierro Island, Canary Archipelago, Spain. In Cross-Border Cooperation (CBC) Strategies for Sustainable Development; IGI GLOBAL: Hershey, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 216–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pezzi, M.G.; Urso, G. Coping with peripherality: Local resilience between policies and practices. Editorial note. Ital. J. Plan. Pract. 2017, 7, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Máliková, L.; Klobučník, M. Differences in the rural structure of Slovakia in the context of socio-spatial polarisation. Quaest. Geogr. 2017, 36, 125–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kebza, M. The development of peripheral areas: The case of West Pomeranian Voivodeship, Poland. Morav. Geogr. Rep. 2018, 26, 69–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pileček, J.; Jančák, V. Theoretical and methodological aspects of the identification and delimitation of peripheral areas. Acta Univ. Carol. Geogr. 2011, 46, 43–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Copus, A.; Mantino, F.; Noguera, J. Inner peripheries: An oxymoron or a real challenge for territorial cohesion? Ital. J. Plan. Pract. 2017, 7, 24–49. [Google Scholar]

- Spiekermann, K.; Neubauer, J. European Accessibility and Peripherality: Concepts, Models and Indicators; Spiekermann & Wegener, Urban and Regional Research (S&W): Dortmund, Germany; Nordregio—Nordic Centre for Spatial Development: Stockholm, Sweden, 2002; p. 9. [Google Scholar]

- Lutter, H.; Pütz, T.; Spangenberg, M. Accessibility and Peripherality of Community Regions: The Role of Road, Long-Distance Railways and Airport Networks, Report to the European Commission, DG XVI; Bundesforschungsanstalt für Landeskunde und Raumordnung: Bonn, Germany, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Lutter, H.; Pütz, T.; Spangenberg, M. Lage und Erreichbarkeit der Regionen in der EGund der Einfluß der Fernverkehrssysteme, Forschungen zur Raumentwicklung; Bundesforschungsanstalt für Landeskunde und Raumordnung: Bonn, Germany, 1993; Volume 23. [Google Scholar]

- Schürmann, C.; Spiekermann, K.; Wegener, M. Accessibility indicators. In Berichte aus dem Institut für Raumplanung; IRPUD: Dortmund, Germany, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Spiekermann, K.; Wegener, M. Trans-European Networks and Unequal Accessibility in Europe. Eur. J. Reg. Dev. 1996, 4, 35–42. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, J.; González, R.; Gómez, G. The European high-speed train network: Predictedeffects on accessibility patterns. J. Transp. Geogr. 1996, 4, 227–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gutiérrez, J.; Urbano, P. Accessibility in the European Union: The impact of thetrans-European road network. J. Transp. Geogr. 1996, 4, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Copus, A.K. A New Peripherality Index for European Regions, Report Prepared for the Highlands and Islands European Partnership; Rural Policy Group, Agricultural and Rural Economics Department, Scottish Agricultural College: Aberdeen, UK, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Copus, A.K. Peripherality and peripherality indicator. North J. Nordregio 1997, 10, 11–15. [Google Scholar]

- Schürmann, C.; Talaat, A. Towards a European Peripherality Index. Report for General Directorate XVI Regional Policy of the European Commission, Berichte aus dem Institut für Raumplanung 53; IRPUD: Dortmund, Germany, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Spiekermann, K.; Wegener, M.; Copus, A. Review of Peripherality Indices and Identification of ‘Baseline Indicator’: Deliverable 1 of AsPIRE—Aspatial Peripherality, Innovation, and the Rural Economy; IRPUD, S&W: Dortmund, Germany; SAC: Aberdeen, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Naranjo, J.M. Impacts on the social cohesion of mainland Spain’s future motorway and high-speed rail networks. Sustainability 2016, 8, 624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Vulevic, A. Demographic response to accessibility improvement in depopulation cross border regions: The Case of Euro region Danube 21 in Serbia. In Proceeding Book, Faculty of Geography; University of Belgrade: Belgrade, Serbia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Program for Cross-Border Cooperation between Spain and Portugal for the Period 2007–2013. Available online: http://www.poctep (accessed on 20 April 2021).

- ECORYS. Strategic Evaluation on Transport Investment Priorities under Structural and Cohesion Funds for the Programming Period 2007-2013. No. 2005.CE.16.0.AT.014; ECORYS, Nederland BV: Rotterdam, The Netherlands, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Copus, A.; Hopkins, J. Mapping Rural Socio-Economic Performance, a Report for the Scottish Government. 2015. Available online: https://www.hutton.ac.uk/sites/default/files/ (accessed on 30 April 2021).

- Espon. Territorial Dynamics in Europe: Trends in Accessibility; Territorial Observation No. 2; Espon: Luxembourg, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Kuhn, M. Peripheralisation: Theoretical Concepts Explaining Socio-Spatial Inequalities. Eur. Plan. Stud. 2015, 23, 367–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gould, P. Spatial Diffusion; Commission on College Geography, Association of American Geographers: Washington, DC, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Kaganskii, V. Inner Periphery is a New Growing Zone of Russia’s Cultural Landscape. Reg. Res. Russ. 2013, 3, 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mantino, F.; Fano, G. New Concepts for Territorial Rural Development in Europe: The Case of Most Remote Rural Areas in Italy. In Proceedings of the XXVI Congress of the European Society of Rural Sociologist, Aberdeen, UK, 18–21 August 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Pitarch, M.D. Measuring equity and social sustainability through accessibility to public services by public transport. The case of the Metropolitan Area of Valencia (Spain). Eur. J. Geogr. 2013, 4, 64–85. [Google Scholar]

- Torre, A.; Rallet, A. Proximity and localization. Reg. Stud. 2005, 39, 47–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaishar, A.; Zapletalová, J. Small towns as centres of rural micro-regions. Eur. Countrys. 2008, 2, 70–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wallerstein, I. Geopolitics and Geoculture: Essays on the Changing World System; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Walls, D. Internal colony or internal periphery? A critique of current models and an alternative formulation. In Colonialism in Modern America: The Appalachian Case; Appalachian State University: Boon, NC, USA, 1978; pp. 319–349. [Google Scholar]

- Weisfelder, R. Lesotho and the inner periphery in the new South Africa. J. Mod. Afr. Stud. 1992, 30, 643–668. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Spatial Planning Observation Network. PROFECY—Processes, Features and Cycles of Inner Peripheries in Europe (Inner Peripheries: National Territories Facing Challenges of Access to Basic Services of General Interest) Applied Research Final Report. Executive Summary. Version 07/12/2017; European Union: Luxembourg, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- European Spatial Planning Observation Network. Cros Border Public Services CPS. 2018. Target Analyses of Cros Border Public Services. Final Report; European Union: Luxembourg, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- European Territorial Observatory Network. Available online: https://www.espon.eu/2020 (accessed on 20 May2021).

| Authors | Spatial Disparities | Changing Pattern through Time |

|---|---|---|

| Keeble et al. [10,11] | Clear core–periphery pattern | Disparities have increased in past periods |

| Lutter et al. [33] | Existing, but scope depends on destination activities considered | Travel time benefits for peripheral regions, daily accessibility increases in central regions |

| Spiekermann and Wegener [35,36] | Clear core–periphery pattern plus clear center-hinterland disparities in all European countries | Increasing disparities induced by TEN |

| Gutierrez and Urbano [37,38] | Clear core–periphery pattern | Decreasing disparities induced by TEN |

| Copus [39,40] | Clear core–periphery pattern | Dynamics not considered |

| Wegener et al., [24,25] | Different core–periphery patterns for different transport modes | Increasing or decreasing disparities is an outcome of the indicator chosen |

| Schürmann and Talaat [41] | Clear core–periphery pattern for road transport | Improvements mainly for EU candidate countries |

| Spiekermann et al. [32,42] | Clear core–periphery pattern, but very different degrees of peripherality; high similarity of peripherality in national and European context | Dynamics not considered |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Gómez, J.M.N.; Vulevic, A.; Couto, G.; Alexandre Castanho, R. Accessibility in European Peripheral Territories: Analyzing the Portuguese Mainland Connectivity Patterns from 1985 to 2020. Infrastructures 2021, 6, 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures6060092

Gómez JMN, Vulevic A, Couto G, Alexandre Castanho R. Accessibility in European Peripheral Territories: Analyzing the Portuguese Mainland Connectivity Patterns from 1985 to 2020. Infrastructures. 2021; 6(6):92. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures6060092

Chicago/Turabian StyleGómez, José Manuel Naranjo, Ana Vulevic, Gualter Couto, and Rui Alexandre Castanho. 2021. "Accessibility in European Peripheral Territories: Analyzing the Portuguese Mainland Connectivity Patterns from 1985 to 2020" Infrastructures 6, no. 6: 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures6060092

APA StyleGómez, J. M. N., Vulevic, A., Couto, G., & Alexandre Castanho, R. (2021). Accessibility in European Peripheral Territories: Analyzing the Portuguese Mainland Connectivity Patterns from 1985 to 2020. Infrastructures, 6(6), 92. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures6060092