Learning from Incidents in Socio-Technical Systems: A Systems-Theoretic Analysis in the Railway Sector

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

3. Methods

3.1. System-Theoretic Accident Model and Process

- Safety constraints: the most important role in STAMP is not the event, but the constraints, the events that lead to losses occur only because safety constraints have not been successfully applied. As technology advances, the identification and enforcement of safety constraints become increasingly hard; in the past, many constraints were physical, related to the strength of the materials or equipment, therefore, the constraints allowed the use of passive controls that ensured safety as long as the physical presence existed. On the other hand, active controls require certain actions to provide protection in: (i) the detection of a hazards event; (ii) the measurement of variables; (iii) the interpretation of measurements; (iv) the response.The introduction of active controls, e.g., electromechanical controls, allowed operators to control the process from a great distance. However, direct contact with the process generates a possible loss of information, and consequentially, the additional causation of errors. To provide all the necessary information, designers must provide feedback on the actions of the operators and any errors that may have occurred.

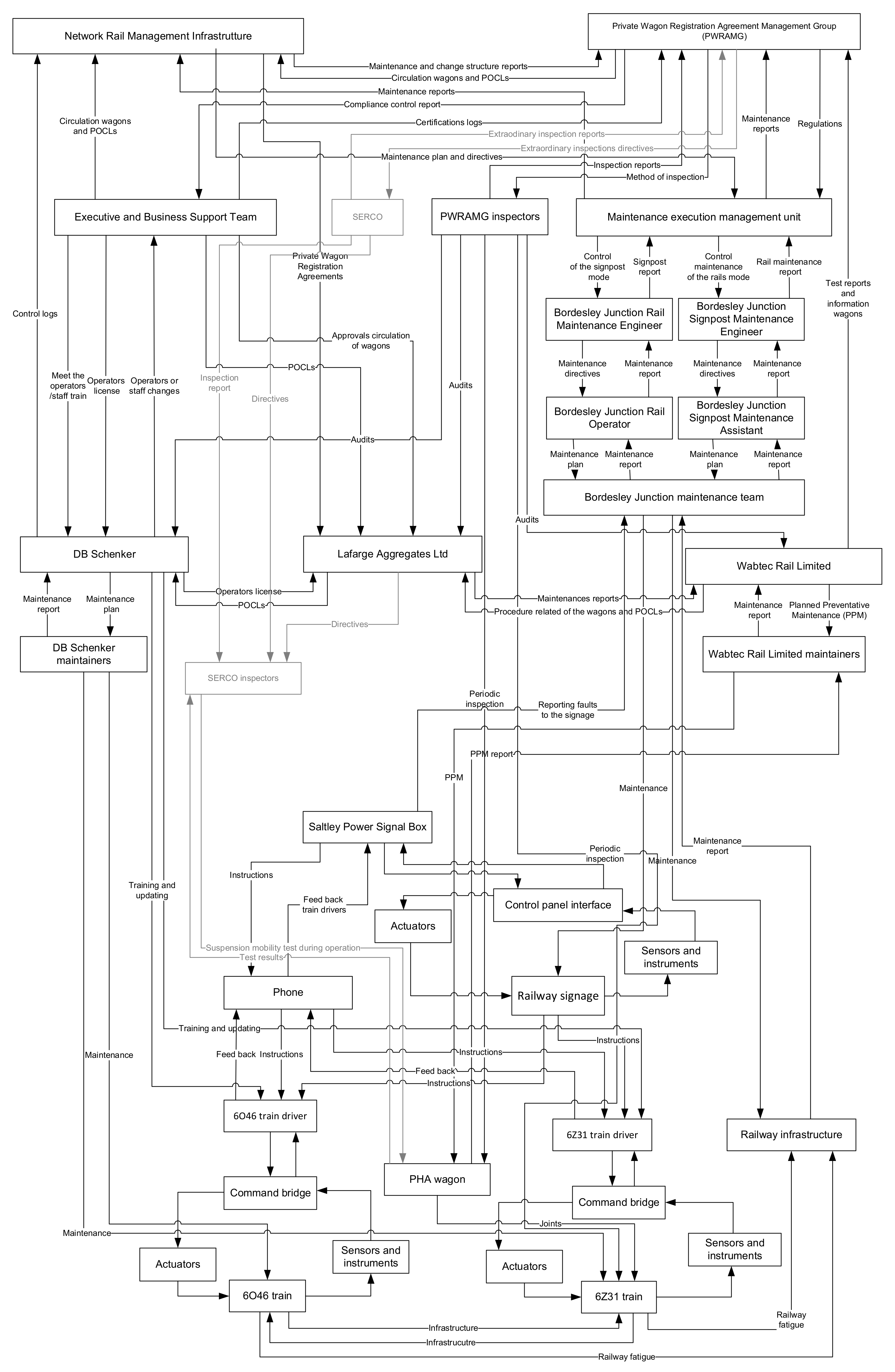

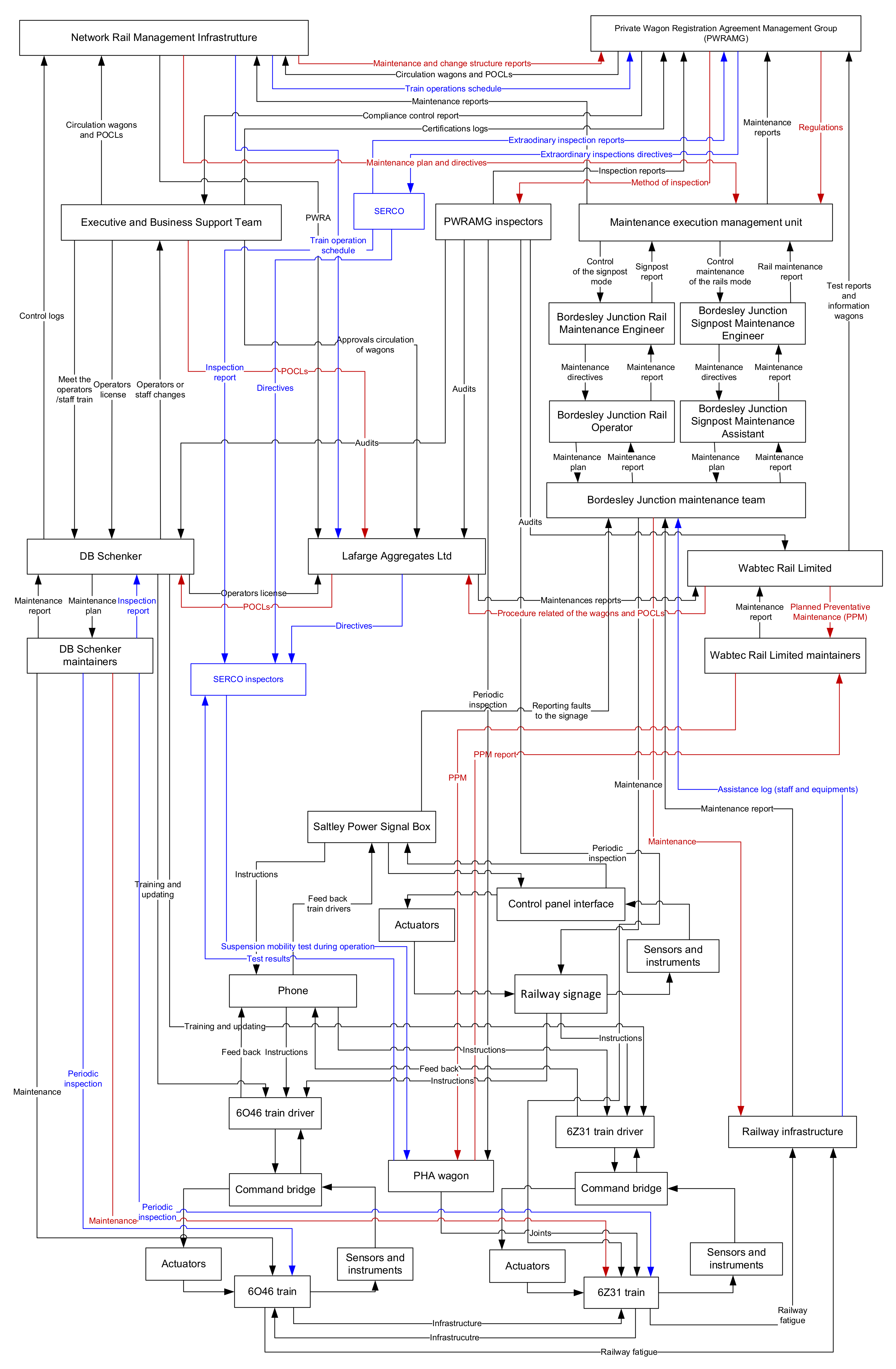

- Hierarchical Safety Control Structure: each level imposes constraints on the underlying layers to control their behavior. Control processes work between the layers to control the processes at the lower level and to enforce safety constraints. Incidents occur when audit processes provide insufficient control and/or safety constraints are violated; some examples of those could be: (i) missing constraints; (ii) inadequate safety-check actions; (iii) poor communication; (iv) incorrect procedures; (v) lack of feedback to detect errors. Therefore, among the hierarchical levels of each control structure, downward communication channels are required to provide information to impose constraints and upward communication channels to obtain feedback and measure to how much the constraints are respected.The control structures always change over time, especially those that include human components, which is why the controls must not necessarily be applied in an authoritarian way by imposing rules or requirements; it is possible to set objectives to be achieved at the lower levels and leave them the decision on the best way to achieve the required result.

- Process Model: The model of process plays an important role in understanding why accidents occur; why humans provide certain control over safety-critical systems and in the design of safety systems. Each controller—either human or automated—needs a process model in a STAMP formulation. The models may contain only two variables or could be very complicated with many parameters. To define a process model, it is necessary to isolate the defined control laws and the value of the variables over time, and to relate them to the varieties of execution: incorrect process models; incorrect commands given; correct actions requested too early or too late, control applied too early or maintained too long.

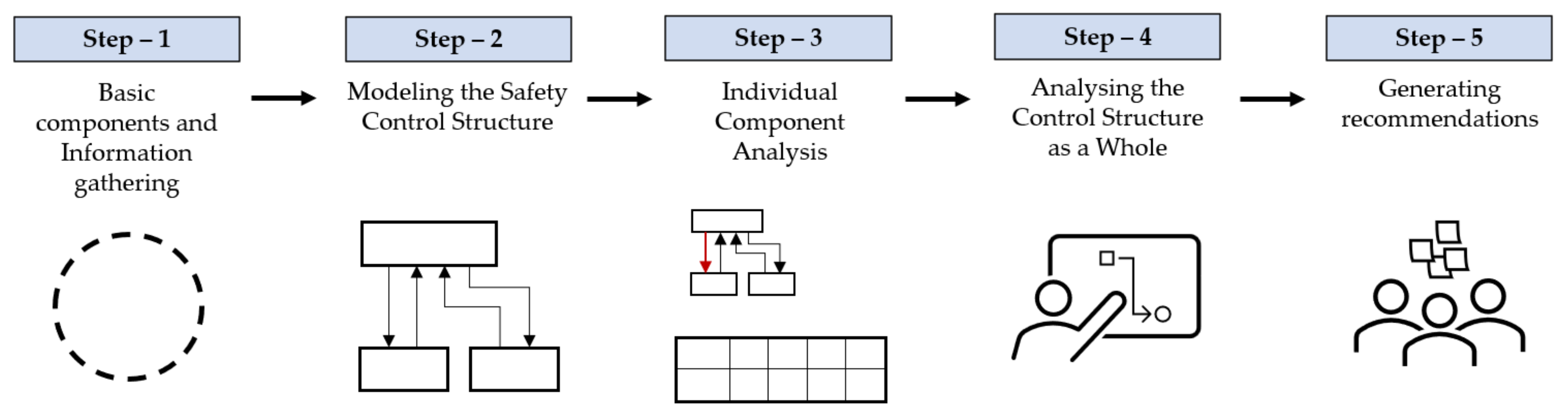

3.2. Causal Analysis Based on System Theory

- Requirements for hazard mitigation: check if the industry provides protection against hazards.

- Controls: verify if the safety equipment (controls) was designed to satisfy the above hazard mitigation requirements.

- Missing or inadequate controls that might have prevented the accident.

- Failures: check for damage in the process equipment.

- Unsafe interactions: verify if there were dangerous interactions among the system components in the accidents caused.

- Contextual factors: verify if there are factors that can influence the process.

- Summary of the roles: inspect the roles of the components in the accident.

- Component responsibilities related to the accident.

- Contribution (actions, lack of actions, decisions) to the hazardous state.

- Flaws in the mental/process model contributing to the actions.

- Contextual factors explaining the actions, decisions, and process model flaws.

- Communication and coordination.

- The safety information system.

- Safety culture.

- Design of the safety management system.

- Changes and dynamics over time, in the system and in the environment.

- Internal and external economic and related factors in the system environment not covered previously in the analysis.

- Assigning responsibility for implementing the recommendations.

- Checking that they have been implemented.

- Establishing a feedback system to determine whether they were effective in strengthening the controls.

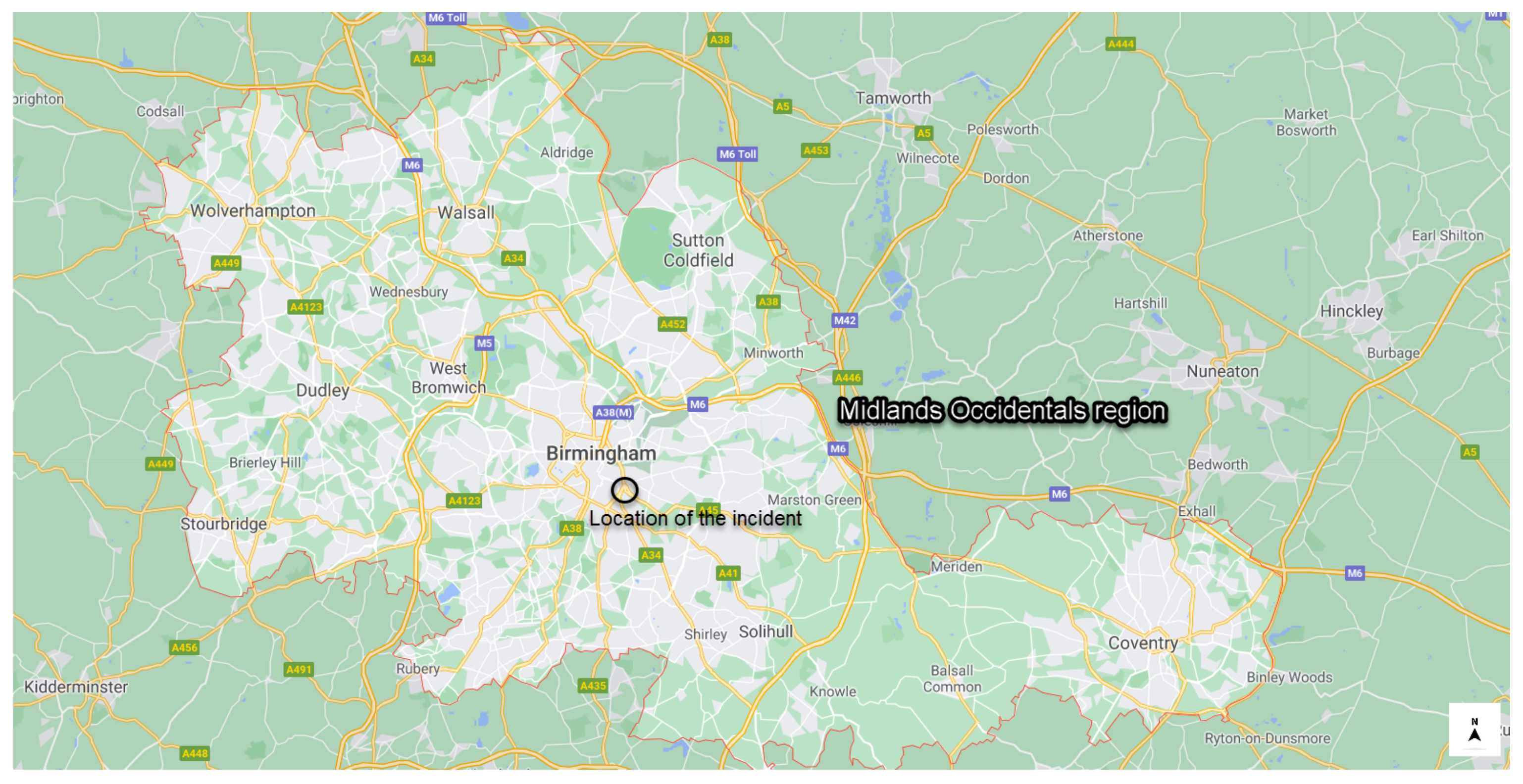

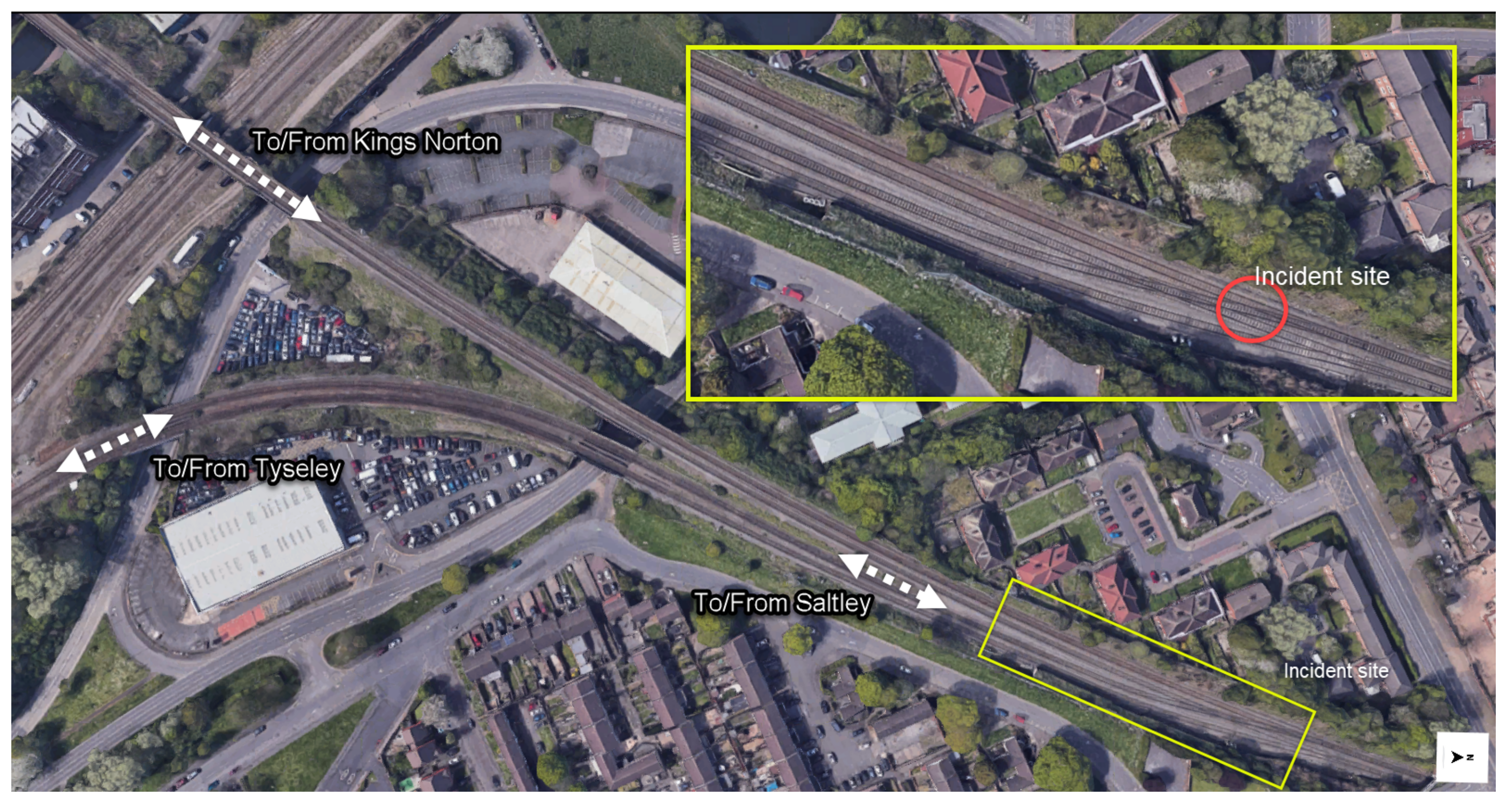

4. Case Study

4.1. Summary of the Accident

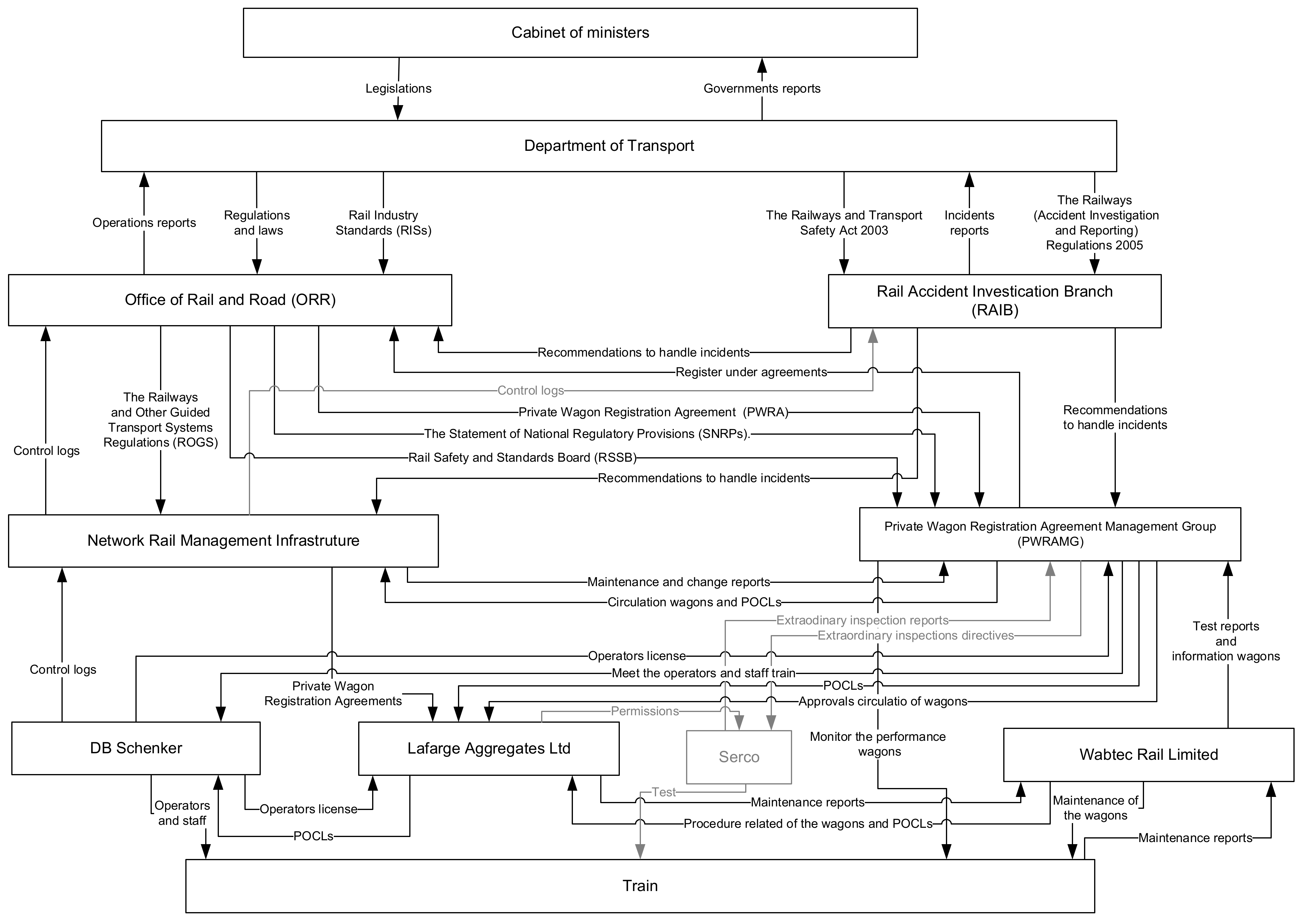

4.2. Causal Analysis Based on System Theory (CAST) Application

- Operating conditions must be set according to the constraints posed by the infrastructure company and the train company.

- Infrastructure maintenance must be timely and effective.

- Train equipment maintenance must be timely and effective.

- The railway signage system must be able to communicate the real situation to the driver.

- The braking system must function properly when passing over a crossover.

- The safety system of the train must protect staff in case of derailment.

- Warnings and other measures must be available to protect operators and citizens close to crossovers.

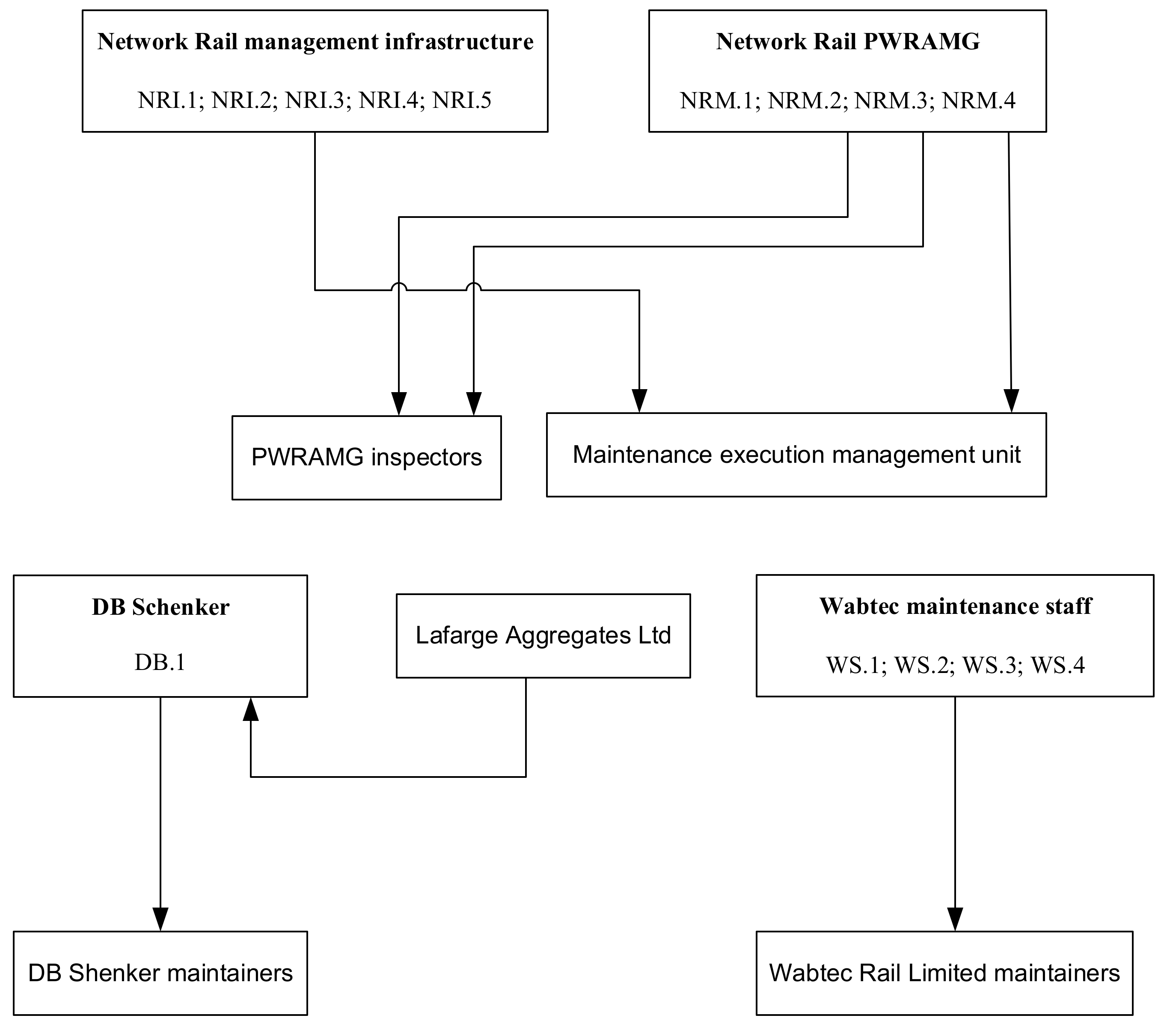

- NRI.1

- The maintenance team were carrying out measured shovel packing repairs at a track joint before the first track twist and at the joints within the switches and crossing for the junction after the second track twist. The aligned waveforms for the section of track with the track twists did not change throughout 2011, but it did change over time in the vicinity of the joints which was as a result of the work done by the maintenance team.

- NRI.2

- The maintenance team had carried out similar repairs at these joints several times in the past. They did not measure the cant in the section of plain line between the joints, so they did not find the reported track twists. Therefore, the track twists went unrepaired.

- NRI.3

- Network Rail maintenance had arranged for a tamping shift to take place at Bordesley Junction during an overnight engineering possession on 21 and 22 August. The work started over two hours later than planned as the tampers did not arrive at their starting places at Bordesley Junction until 02:45 h. The tamping shift did take place that night, but it ran short of time so not all of the planned work could be done.

- NRI.4

- The ballast in places at Bordesley Junction was contaminated with dirt and dust, especially near to the overbridged section. Witnesses suggested that the formation beneath the track bed at the junction was poor due to water discharging from the drains on the overbridged section onto the track at the junction.

- NRI.5

- Although the rail was well within its maintenance limits, the side wear changed the contact angle between the wheel flange and the rail head. This increased the likelihood of the flange climbing onto the rail head.

- NRM.1

- The report issued by Serco in 2009 shows the problems in the suspension but at the moment of the incident: (i) no modifications had been made to the suspension on REDA 16066; (ii) the way in which the PHA wagon fleet was operated on the national network had not been reassessed; (iii) no formal changes had been made to the wagons’ maintenance regime.

- NRM.2

- The Network Rail PWRAMG identified a number of changes to the suspension components to reduce the likelihood of the wheels locking up but did not set a timescale for completion of this assessment.

- NRM.3

- The Network Rail PWRAMG knew from the testing carried out by Serco that the suspensions were prone to lock up, but the wagon fleets continued running in service; based on the incident and failures data, they decided that no further action was needed.

- NRM.4

- The Network Rail PWRAMG issued a letter to all private wagon owners when provided details of the proposed engineering changes and the new maintenance checks. It did not mandate that the maintenance checks should be carried out; the maintenance checks became mandatory nineteen months after they were first proposed by the PWRAMG.

- WS.1

- The maintainers followed the instructions for each type of examination, each instruction called for specific components within the suspension to be examined. However, some were not fully visible or could not be measured unless the suspension was disassembled by lifting the wagon and taking the wheelset out.

- WS.2

- The damper pot liner wear plate on the trailing left-hand wheel’s suspension was worn beyond its maintenance limit.

- WS.3

- While the prescribed maintenance process for REDA 16066 was being completed, this did not lead the maintainers to identify and change worn components within the suspension before this wear increased the likelihood of the suspension locking-up.

- WS.4

- Wabtec did not include the new checks within the maintenance plans in 2009 or on any of the documentation that is filled in when an examination takes place.

- DB.1

- The effectiveness of grease in reducing the level of friction between the wheel flange and the rail was limited by its position low down on the inside face. It was also the case that at the time of derailment the rails were dry, and therefore the level of friction was higher than it would have been if they were wet.

- The control action (Regulations) from Network Rail PWRAMG to Maintenance Execution management unit that delivers to the Maintenance execution management unit. Since they did not mandate the changes in the maintenance and inspections of the Railway structure, and the maintenance checks became mandatory nineteen months after they were first suggested.

- The control action (Method of inspection) from Network Rail PWRAMG to PWRAMG inspectors that provides the guidelines for inspection of the wagons. Since they did not modify the threshold in the measurement of the dynamic track twist, a 3-m track twist more severe than 1 in 200 reduced the load on the leading right-hand wheel, causing the flange to climb onto the rail head. Although trains were permitted to operate over track with this degree of track twist, the derailment is unlikely to have occurred in its absence.

- The control action (Planned Preventative Maintenance) from Wabtec Rail Limited to Wabtec Rail Limited maintainers that imposed the guideline to repair and monitor the components of the wagons; because they did not implement the changes in the suspension of the wagon PHA, established in the POCL given from Network Rail PAWRAMG and had not included the new checks within the maintenance plans of 2009 or on any of the documentation that is filled in when an examination takes place.

- The control action (Procedure related to the wagons and POCLs) from Wabtec Rail Limited to Lafarge Aggregates Ltd that impose the work condition of the wagon and report through private owner circulation letter (POCL) the changes related with the regulations and test.

- The control action (PPM) from Wabtec Rail Limited maintainers of PHA wagon that repairs and monitors the components of the wagons, because the maintainers followed the instructions for each type of examination. However, some were not fully visible or could not be measured unless the suspension was disassembled by lifting the wagon and taking the wheelset out. While the prescribed maintenance process for REDA 16066 was being complied with, this did not lead the maintainers to identify and change worn components within the suspension before this wear increased the likelihood of the suspension locking-up.

- The feedback (PPM report) from Wabtec Rail Limited maintainers of PHA wagon that describes the changes and maintenance of the wagon during the PPM. Since February 2010, there was no record of any work being done to the trailing corner on the left-hand side, but REDA 16066 was last lifted in October 2010 during a PPM examination.

- The control action (POCL) from Executive and Business support team to Lafarge Aggregates Ltd that communicates to the owners of the trains any change in the policies and the regulations related to the operations of the train or the conditions of the work staff. Since the POCL in 2009, the Executive and Business support team did not make any effort to convince the owners to carry out the changes necessary in the suspension wagon to avoid the locking up of the wheel.

- The control action (Maintenance) from DB Schenker maintainers to 6Z31 train that inspects, repairs and maintains the train equipment. The damper pot liner wear plate on the trailing left-hand wheel’s suspension was worn beyond its maintenance limit.

- The control action (Maintenance) from Border Junction maintenance team to Railway infrastructure that inspects and repairs the railway structure. The team did not repair the twisted track section where the event occurred. On 25 August, the up and down main Bordesley lines and the track over the junction were inspected by Network Rail maintenance staff on foot. No problems were found by the staff that carried out this inspection. It was also the case that at the time of derailment, the rails were dry, and therefore the level of friction was higher than it would have been if they were wet.

- The track twist measurement process should become a periodic inspection. Rather than being interpreted as ad hoc consultations, a formal periodic process to ensure that track twists are within standards should be required. Even though this measurements process can be outsourced to an external company (such as Serco, for the event under investigation), there are no restrictions in doing it in-house. For the monitoring, it should be taken into consideration the fact that the cant distance varies depending on the load. As such, it could be possible to start using sensors that automatize the monitoring process on sample parts of the lines.

- A formal inspection for the suspension system should be carried out. This recommendation starts from the missed correspondence of components for the train 6Z31 involved in the event, as maintained by DB Schenker. This should be a regulated action in the charge of the train company.

- The inspection of suspension shall be part of a formalized information exchange process. The results of inspections as carried out by the train companies should be validated by the Network Rail PWRAMG.

- Train operations should be shared between the train operating company and Network Rail to ensure the smooth and effective management of the maintenance plan.This recommendation emerges from the need to properly schedule time-based maintenance interventions for the train owned by a company and for Network rail to establish properly the time scale of each intervention.

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Underwood, P.; Waterson, P. Systems thinking, the Swiss Cheese Model and accident analysis: A comparative systemic analysis of the Grayrigg train derailment using the ATSB, AcciMap and STAMP models. Accid. Anal. Prev. 2014, 68, 75–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bugalia, N.; Maemura, Y.; Ozawa, K. Organizational and institutional factors affecting high-speed rail safety in Japan. Saf. Sci. 2020, 128, 104762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paltrinieri, N.; Bonvicini, S.; Spadoni, G.; Cozzani, V. Cost-Benefit Analysis of Passive Fire Protections in Road LPG Transportation. Risk Anal. 2012, 32, 200–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriarca, R.; Falegnami, A.; Costantino, F.; Di Gravio, G.; De Nicola, A.; Villani, M.L. WAx: An integrated conceptual framework for the analysis of cyber-socio-technical systems. Saf. Sci. 2021, 136, 105142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Righi, A.W.; Saurin, T.A. Complex socio-technical systems: Characterization and management guidelines. Appl. Ergon. 2015, 50, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leveson, N. Engineering a Safer World: Systems Thinking Applied to Safety; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2011; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Ibrion, M.; Paltrinieri, N.; Nejad, A.R. Learning from failures: Accidents of marine structures on Norwegian continental shelf over 40 years time period. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 111, 104487. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Carvalho, P.V.R. The use of Functional Resonance Analysis Method (FRAM) in a mid-air collision to understand some characteristics of the air traffic management system resilience. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2011, 96, 1482–1498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveson, N. A new accident model for engineering safer systems. Saf. Sci. 2004, 42, 237–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Rasmussen, J. Risk management in a dynamic society: A modeling problem. Saf. Sci. 1997, 27, 183–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmussen, J.; Svedung, I. Proactive Risk Management in a Dynamic Society; Swedish Rescue Services Agency: Karlstad, Sweden, 2000; Volume 1, ISBN 9172530847. [Google Scholar]

- Li, W.; Zhang, L.; Liang, W. An Accident Causation Analysis and Taxonomy (ACAT) model of complex industrial system from both system safety and control theory perspectives. Saf. Sci. 2017, 92, 94–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveson, N. CAST handbook: How to Learn More from Incidents and Accidents. 2018, Volume 1, p. 188. Available online: http://sunnyday.mit.edu/CAST-Handbook.pdf (accessed on 20 February 2022).

- Leveson, N.; Daouk, M.; Dulac, N.; Marais, K. Applying STAMP in Accident Analysis. 2003, pp. 1–26. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/102905 (accessed on 25 February 2022).

- Li, F.; Wang, W.; Xu, J.; Dubljevic, S.; Khan, F.; Yi, J. A CAST-based causal analysis of the catastrophic underground pipeline gas explosion in Taiwan. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2020, 108, 104343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altabbakh, H.; AlKazimi, M.A.; Murray, S.; Grantham, K. STAMP—Holistic system safety approach or just another risk model? J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2014, 32, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriarca, R.; Chatzimichailidou, M.; Karanikas, N.; Di Gravio, G. The past and present of System-Theoretic Accident Model And Processes (STAMP) and its associated techniques: A scoping review. Saf. Sci. 2022, 146, 105566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, W.; Dubljevic, S.; Khan, F.; Xu, J.; Yi, J. Analysis on accident-causing factors of urban buried gas pipeline network by combining DEMATEL, ISM and BN methods. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2019, 61, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, D.; Wang, Y.; Meng, Y.; Zhang, Z. An Improved Data Anomaly Detection Method Based on Isolation Forest. In Proceedings of the 2017 10th International Symposium on Computational Intelligence and Design (ISCID), Hangzhou, China, 9–10 December 2017; pp. 287–291. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, L.; Liang, W.; Zhang, L.; Zhang, H.; Lu, Z.; Shan, J. A comprehensive risk evaluation method for natural gas pipelines by combining a risk matrix with a bow-tie model. J. Nat. Gas Sci. Eng. 2015, 25, 124–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaban, A.; Abdelwahed, A.; Di Gravio, G.; Afefy, I.H.; Patriarca, R. A systems-theoretic hazard analysis for safety-critical medical gas pipeline and oxygen supply systems. J. Loss Prev. Process Ind. 2022, 77, 104782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patriarca, R.; Ramos, M.; Paltrinieri, N.; Massaiu, S.; Costantino, F.; Di Gravio, G.; Boring, R.L. Human reliability analysis: Exploring the intellectual structure of a research field. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2020, 203, 107102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rong, H.; Tian, J. STAMP-based HRA considering causality within a sociotechnical system: A case of minuteman III missile accident. Hum. Factors 2015, 57, 375–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reason, J. Human Error; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1990; ISBN 9780521306690. [Google Scholar]

- Lower, M.; Magott, J.; Skorupski, J. A System-Theoretic Accident Model and Process with Human Factors Analysis and Classification System taxonomy. Saf. Sci. 2018, 110, 393–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robertson, J.; Kothakonda, A. CAST Analysis of the International Space Station EVA 23 Suit Water Intrusion Mishap. In Proceedings of the International Astronautical Congress, Bremen, Germany, 1–5 October 2018. IAC-18-45324. [Google Scholar]

- Virdin, J.; Vegh, T.; Jouffray, J.-B.; Blasiak, R.; Mason, S.; Österblom, H.; Vermeer, D.; Wachtmeister, H.; Werner, N. The Ocean 100: Transnational Corporations in the Ocean Economy. Sci. Adv. 2021, 7, 8041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrion, M.; Paltrinieri, N.; Nejad, A.R. Learning from failures in cruise ship industry: The blackout of Viking Sky in Hustadvika, Norway. Eng. Fail. Anal. 2021, 125, 105355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Kim, H.; Liu, Y.; Lundteigen, M.A. Combining system-theoretic process analysis and availability assessment: A subsea case study. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part O J. Risk Reliab. 2019, 233, 520–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stringfellow, M.V.; Dierks, M.M.; Pysessor, A. Accident Analysis and Hazard Analysis for Human and Organizational Factors; Massachusetts Institute of Technology: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Mogles, N.; Padget, J.; Bosse, T. Systemic approaches to incident analysis in aviation: Comparison of STAMP, agent-based modelling and institutions. Saf. Sci. 2018, 108, 59–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leveson, N.; Samost, A.; Dekker, S.; Finkelstein, S.; Raman, J. A Systems Approach to Analyzing and Preventing Hospital Adverse Events. J. Patient Saf. 2016, 16, 162–167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Nazir, S.; Øvergård, K.I. A STAMP-based causal analysis of the Korean Sewol ferry accident. Saf. Sci. 2016, 83, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Düzgün, H.S.; Leveson, N. Analysis of soma mine disaster using causal analysis based on systems theory (CAST). Saf. Sci. 2018, 110, 37–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrion, M.; Paltrinieri, N.; Nejad, A.R. Learning from non-failure of Onagawa nuclear power station: An accident investigation over its life cycle. Results Eng. 2020, 8, 100185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, A.; Mclean, S.; Dallat, C.; Walker, G.H.; Waterson, P.; Stanton, N.A.; Salmon, P.M. Systems thinking-based risk assessment methods applied to sports performance: A comparison of STPA, EAST-BL, and Net-HARMS in the context of elite women’s road cycling. Appl. Ergon. 2021, 91, 103297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sultana, S.; Andersen, B.S.; Haugen, S. Identifying safety indicators for safety performance measurement using a system engineering approach. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2019, 128, 107–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, D.P.; Hirata, C.; Nadjm-Tehrani, S. A STAMP-based ontology approach to support safety and security analyses. J. Inf. Secur. Appl. 2019, 47, 302–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salmon, P.M.; Cornelissen, M.; Trotter, M.J. Systems-based accident analysis methods: A comparison of Accimap, HFACS, and STAMP. Saf. Sci. 2012, 50, 1158–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ando, T.; Wang, B.; Hisazumi, K.; Kong, W.; Fukuda, A.; Michiura, Y.; Sakemi, K.; Matsumoto, M. Verification model translation method toward behavior model for CAST. In Proceedings of the 2018 5th International Conference on Dependable Systems and Their Applications, DSA 2018, Dalian, China, 22–23 September 2018; Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc.: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2018; pp. 142–147. [Google Scholar]

- RIAB. Rail Accident Report, Derailment at Bordesley Junction, Birmingham 26 August 2011; Rail Accident Investigation Branch: Derby, UK, 2012.

- Hamim, O.F.; Hasanat-E-Rabbi, S.; Debnath, M.; Hoque, M.S.; McIlroy, R.C.; Plant, K.L.; Stanton, N.A. Taking a mixed-methods approach to collision investigation: AcciMap, STAMP-CAST and PCM. Appl. Ergon. 2022, 100, 103650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landi, R.G.; Montedo, U.B.; Lahoz, C.H.N. Using systems theory for additional risk detection in boiler explosions in Brazil. Saf. Sci. 2022, 152, 105761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, M.; Hong, L.; Yu, M.H.; Fei, Q. STAMP-based analysis on the railway accident and accident spreading: Taking the China-Jiaoji railway accident for example. Saf. Sci. 2010, 48, 544–555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, T.; Zhong, D.; Zhong, H. A STAMP Analysis on the China-Yongwen Railway Accident; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; Volume 7612. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, J.H.; Wu, B. A STAMP-based Causal Analysis of the Beiyou25 Grounding Accident. In Proceedings of the Prognostics and System Health Management Conference, Qingdao, China, 25–27 October 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Simone, F.; Patriarca, R. A simulation-driven cyber resilience assessment for water treatment plants. In Proceedings of the 32nd European Safety and Reliability Conference, Dublin, Ireland, 28 August–1 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Patriarca, R.; Simone, F.; Di Gravio, G. Modelling cyber resilience in a water treatment and distribution system. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2022, 226, 108653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leerapan, B.; Teekasap, P.; Urwannachotima, N.; Jaichuen, W.; Chiangchaisakulthai, K.; Udomaksorn, K.; Meeyai, A.; Noree, T.; Sawaengdee, K. System dynamics modelling of health workforce planning to address future challenges of Thailand’s Universal Health Coverage. Hum. Resour. Health 2021, 19, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Landucci, G.; Paltrinieri, N. A methodology for frequency tailorization dedicated to the Oil & Gas sector. Process Saf. Environ. Prot. 2016, 104, 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Zarei, E.; Khan, F.; Yazdi, M. A dynamic risk model to analyze hydrogen infrastructure. Int. J. Hydrogen Energy 2020, 46, 4626–4643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Organization | Roles and Responsibilities |

|---|---|

| Cabinet Minister (1) | S/he manages the guidelines creating legislation to give a general rule for the management of safety and risk in the railway system |

| Department of Transport | It works with other agencies and partners to support the transport network providing policy, guidance, and funding to local authorities |

| Rail Accident Investigation Branch (2) (RAIB) | It works with the other agencies to investigate accidents in order to improve railway safety and inform the industry and the public |

| Office of Rail and Road (3) (ORR) | It regulates the rail industry’s health and safety performance, holds Network Rail and other rail infrastructure networks to account and makes sure that the rail industry is competitive and fair |

| Network Rail Management Infrastructure | It manages and regulates the processes to guarantee the operation of the railway systems |

| Private Wagon Registration Agreement Management Group (4) (PWRAMG) | It works to manage the guidelines and control the staff related with the system |

| Wabtec Rail Limited (5) | It works to provide maintenance of the trains and its components |

| DB Schenker | It operates and contracts the staff of the trains |

| Lafarge Aggregates Ltd. | The owners of the trains which operate on the United Kingdom (UK) railway system |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nakhal Akel, A.J.; Di Gravio, G.; Fedele, L.; Patriarca, R. Learning from Incidents in Socio-Technical Systems: A Systems-Theoretic Analysis in the Railway Sector. Infrastructures 2022, 7, 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures7070090

Nakhal Akel AJ, Di Gravio G, Fedele L, Patriarca R. Learning from Incidents in Socio-Technical Systems: A Systems-Theoretic Analysis in the Railway Sector. Infrastructures. 2022; 7(7):90. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures7070090

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakhal Akel, Antonio Javier, Giulio Di Gravio, Lorenzo Fedele, and Riccardo Patriarca. 2022. "Learning from Incidents in Socio-Technical Systems: A Systems-Theoretic Analysis in the Railway Sector" Infrastructures 7, no. 7: 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures7070090

APA StyleNakhal Akel, A. J., Di Gravio, G., Fedele, L., & Patriarca, R. (2022). Learning from Incidents in Socio-Technical Systems: A Systems-Theoretic Analysis in the Railway Sector. Infrastructures, 7(7), 90. https://doi.org/10.3390/infrastructures7070090