Assessing Changes in Surgical Site Infections and Antibiotic Use among Caesarean Section and Herniorrhaphy Patients at a Regional Hospital in Sierra Leone Following Operational Research in 2021

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Study Setting

2.2.1. General Setting

2.2.2. Specific Setting

2.3. Dissemination Details and Recommendations of the First Study

2.4. Study Population and Period

2.5. Data Variables

2.6. Data Collection

2.7. Data Validation and Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Dissemination Details of the First Study

3.2. Recommendations of the First Study

3.3. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Study Patients

3.4. Clinical Characteristics of the Study Patients

3.5. Surgical Site Infections

3.6. Type of Surgical Procedure to the Type of Surgery

3.7. Timing and Type of Antibiotics Administered

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Protocol for Surgical Site Infection Surveillance with a Focus on Settings with Limited Resources. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/protocol-for-surgical-site-infection-surveillance-with-a-focus-on-settings-with-limited-resources (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- The Second Global Patient Safety Challenge: Safe Surgery Saves Lives. Available online: https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/70080 (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Global Guidelines for the Prevention of Surgical Site Infection, 2nd Ed. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/global-guidelines-for-the-prevention-of-surgical-site-infection-2nd-ed (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Ngaroua; Ngah, J.E.; Bénet, T.; Djibrilla, Y. [Incidence of surgical site infections in sub-Saharan Africa: Systematic review and meta-analysis]. Pan Afr. Med. J. 2016, 24, 171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chu, K.; Maine, R.; Trelles, M. Cesarean Section Surgical Site Infections in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Multi-Country Study from Medecins Sans Frontieres. World J. Surg. 2015, 39, 350–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Gennaro, F.; Marotta, C.; Pisani, L.; Veronese, N.; Pisani, V.; Lippolis, V.; Pellizer, G.; Pizzol, D.; Tognon, F.; Bavaro, D.F.; et al. Maternal Caesarean Section Infection (MACSI) in Sierra Leone: A Case–Control Study. Epidemiol. Infect. 2020, 148, e40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carshon-Marsh, R.; Squire, J.S.; Kamara, K.N.; Sargsyan, A.; Delamou, A.; Camara, B.S.; Manzi, M.; Guth, J.A.; Khogali, M.A.; Reid, A.; et al. Incidence of Surgical Site Infection and Use of Antibiotics among Patients Who Underwent Caesarean Section and Herniorrhaphy at a Regional Referral Hospital, Sierra Leone. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 4048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakoh, S.; Yi, L.; Sevalie, S.; Guo, X.; Adekanmbi, O.; Smalle, I.O.; Williams, N.; Barrie, U.; Koroma, C.; Zhao, Y.; et al. Incidence and Risk Factors of Surgical Site Infections and Related Antibiotic Resistance in Freetown, Sierra Leone: A Prospective Cohort Study. Antimicrob. Resist. Infect. Control 2022, 11, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakoh, S.; Kanu, J.S.; Conteh, S.K.; Russell, J.B.W.; Sevalie, S.; Williams, C.E.E.; Barrie, U.; Kabia, A.K.; Conteh, F.; Jalloh, M.B.; et al. High Levels of Surgical Antibiotic Prophylaxis: Implications for Hospital-Based Antibiotic Stewardship in Sierra Leone. Antimicrob. Steward Healthc. Epidemiol. 2022, 2, e111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Global Action Plan on Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241509763 (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Sierra Leone: National Strategic Plan for Combating Antimicrobial Resistance. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/sierra-leone-national-strategic-plan-for-combating-antimicrobial-resistance (accessed on 20 June 2023).

- Orelio, C.C.; Hessen, C.; Sanchez-Manuel, F.J.; Aufenacker, T.J.; Scholten, R.J. Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Prevention of Postoperative Wound Infection in Adults Undergoing Open Elective Inguinal or Femoral Hernia Repair. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2020, 2020, CD003769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Team, W.E.R. Ebola Virus Disease in West Africa—The First 9 Months of the Epidemic and Forward Projections. N. Engl. J. Med. 2014, 371, 1481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sierra Leone National Infection Prevention and Control Guidelines_2022. Available online: https://www.afro.who.int/countries/sierra-leone/publication/sierra-leone-national-infection-prevention-and-control-guidelines-2022 (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- Koroma, Z.; Moses, F.; Delamou, A.; Hann, K.; Ali, E.; Kitutu, F.E.; Namugambe, J.S.; Harding, D.; Hermans, V.; Takarinda, K.; et al. High Levels of Antibiotic Resistance Patterns in Two Referral Hospitals during the Post-Ebola Era in Free-Town, Sierra Leone: 2017–2019. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2021, 6, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistic Sierra Leone Stats SL-2021 DIGITAL MID-TERM CENSUS PROVISIONAL RESULTS. Available online: https://www.statistics.sl/index.php/2021-digital-mid-term-census-provisional-results.html (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- WHO Country Cooperation Strategy at a Glance: Sierra Leone. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/WHO-CCU-18.02-SierraLeone (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- World Bank Open Data. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org (accessed on 5 June 2023).

- Statistic Sierra Leone Stats SL-GDP. Available online: https://www.statistics.sl/index.php/gdp.html (accessed on 5 June 2023).

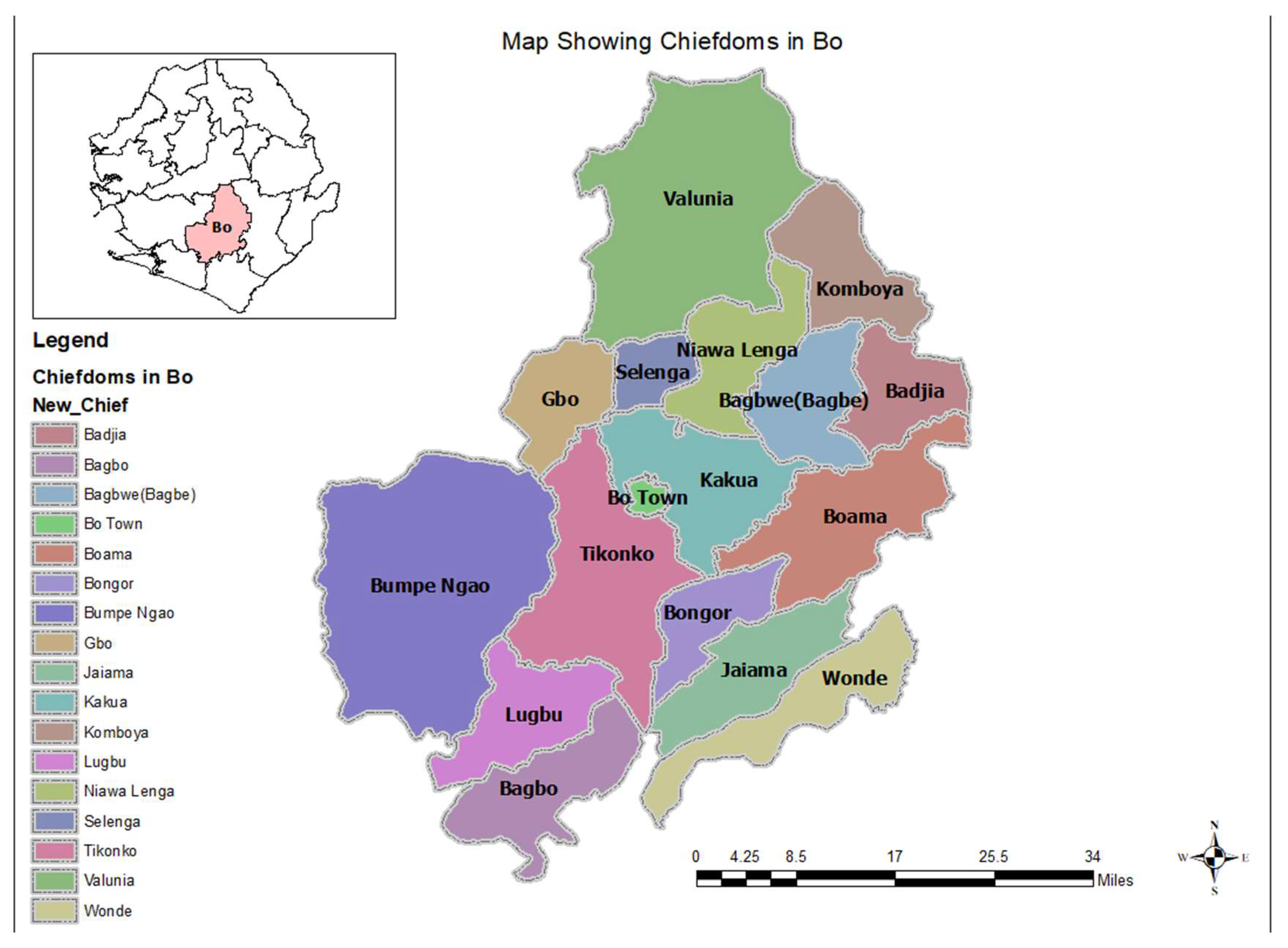

- Reproduce Map of Bo Showing Its Chiefdoms. Available online: https://mail.google.com/mail/u/0/#inbox/FMfcgzGtwMcKCvGnqwNSbVQCJPDnsHQh?projector=1&messagePartId=0.1 (accessed on 26 July 2023).

- Delamou, A.; Camara, B.S.; Sidibé, S.; Camara, A.; Dioubaté, N.; Ayadi, A.M.E.; Tayler-Smith, K.; Beavogui, A.H.; Baldé, M.D.; Zachariah, R. Trends of and Factors Associated with Cesarean Section Related Surgical Site Infections in Guinea. J. Public. Health Afr. 2019, 10, 818. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakoh, S.; Bawoh, M.; Lewis, H.; Jalloh, I.; Thomas, C.; Barlatt, S.; Jalloh, A.; Deen, G.F.; Russell, J.B.W.; Kabba, M.S.; et al. Establishing an Antimicrobial Stewardship Program in Sierra Leone: A Report of the Experience of a Low-Income Country in West Africa. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Jonge, S.W.; Boldingh, Q.J.J.; Solomkin, J.S.; Dellinger, E.P.; Egger, M.; Salanti, G.; Allegranzi, B.; Boermeester, M.A. Effect of Postoperative Continuation of Antibiotic Prophylaxis on the Incidence of Surgical Site Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2020, 20, 1182–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lakoh, S.; John-Cole, V.; Luke, R.D.C.; Bell, N.; Russell, J.B.W.; Mustapha, A.; Barrie, U.; Abiri, O.T.; Coker, J.M.; Kamara, M.N.; et al. Antibiotic Use and Consumption in Freetown, Sierra Leone: A Baseline Report of Prescription Stewardship in Outpatient Clinics of Three Tertiary Hospitals. IJID Reg. 2023, 7, 43–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Antibiotics Portal. Available online: https://aware.essentialmeds.org/resistance (accessed on 6 June 2023).

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P. STROBE Initiative The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) Statement: Guidelines for Reporting Observational Studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.M.V.; Shewade, H.D.; Tripathy, J.P.; Guillerm, N.; Tayler-Smith, K.; Berger, S.D.; Bissell, K.; Reid, A.J.; Zachariah, R.; Harries, A.D. Does Research through Structured Operational Research and Training (SORT IT) Courses Impact Policy and Practice? Public Health Action 2016, 6, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Objective | Variables | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| Objective 1 | Target of dissemination | Previous principal investigator and hospital records |

| Describe the dissemination activities, decisions, and actions taken to reduce the SSIs and the overuse of antibiotics on the maternity and surgical wards of the * BGH following an operational research study (** SORT IT), led by *** TDR and partners, published in March 2022 | Date of dissemination | |

| Place of dissemination | ||

| Mode of dissemination | ||

| Action taken | ||

| Date of action | ||

| Place of action | ||

| Objective 2 | Age in years | Wound dressing book, individual patient medical records |

| To compare the demographic and clinical characteristics between the two study time periods for **** CS and herniorrhaphy patients | Sex (M, F) | |

| Residence | ||

| Referral case or not (cases referred from the ***** PHUs and other hospitals or clinics) | ||

| Marital status | ||

| Co-morbidity | ||

| Date of surgery | ||

| Diagnosis/indication for surgery | ||

| Type of surgical procedure | ||

| Whether elective or emergency surgery | ||

| The American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) score | ||

| Timing/time of day of operation | ||

| Duration of the operation | ||

| Surgical wound classification (four classes from clean to infected wound) | ||

| Date of admission | ||

| Date of discharge | ||

| Objective 3 | Surgical site infection present: Yes or no | Theatre registers, wound dressing book, individual patient medical records, theatre/anesthetist notes |

| On the maternity and surgical wards of the Bo Government Hospital and between two time periods (2021 and 2023): | Type of surgical procedure: Caesarean section or herniorrhaphy | |

| a. To compare the incidence of surgical site infections in CS and herniorrhaphy patients | ||

| b. To compare the type and proportion of antibiotics used among patients. | Antibiotics given: Yes or no | |

| c. To compare the timing of antibiotics used for CSs and herniorrhaphies. | If antibiotics given: Is it pre- or postoperatively | |

| Ampicillin given: Yes or no | ||

| Gentamycin given: Yes or no | ||

| Metronidazole given: Yes or no | ||

| Ceftriaxone given: Yes or no | ||

| Amoxicillin given: Yes or no | ||

| Other antibiotics given: Yes or no |

| Mode of Delivery * | To Whom | Where | When |

|---|---|---|---|

| Presentation Published article Social media | Leadership of the MoHS SL | Office of the Chief Medical Officer | April 2022, The CMO is co-author of this article |

| Presentation Handout/summary brief Published article | Bo Government Hospital management committee | IPC Hall, BGH | May 2022 |

| Presentation Handout/summary brief Published article | Leadership of the National AMR multi-sectorial committee | National SORT IT Dissemination Meeting | May 2022 |

| Clinical meetings Hospital WhatsApp forum | BGH clinicians | IPC Hall, BGH | May 2022 |

| Recommendation | ** Status of Action | Details of Action |

|---|---|---|

| Hospital antimicrobial stewardship program | Not implemented | At the hospital level, no antimicrobial stewardship program was established. However, at the national level, there were plans to establish hospital-based antimicrobial stewardship programs. |

| Educate surgeons, obstetricians and surgical * CHOs on WHO antibiotic treatment guidelines | Not implemented | No training on the WHO antibiotic treatment guidelines was provided to surgeons, obstetricians or surgical community health officers. |

| Monitor and report on antibiotic use | Not implemented | No monitoring or reporting on antibiotic use was performed. |

| Improve hospital IPC | Partially implemented | Hospital IPC focal points and link personnel conducted daily IPC monitoring and weekly hand hygiene audits. However, the hospital hand sanitizer and liquid soap manufacturing unit was not functional from November 2022, resulting in shortages of supplies. |

| Improve the hospital’s records and information system | Fully implemented | Child Health and Mortality Prevention Surveillance (CHAMPS) team supported the Bo Government Hospital management in renovating a records room where hard-copy medical files were properly kept. |

| Review and update the national antibiotic treatment guidelines | Partially implemented | At the national level, funding was sourced, concept notes developed, approval given, and timelines set (second quarter of 2024) for the review of the national standard treatment guidelines and essential medicines list for the inclusion of the *** AWARe classification of antibiotics. |

| Work with the lab directorate to strengthen laboratory services for specimen culture and sensitivity tests | Partially implemented | Further efforts were made by the laboratory directorate to fast track the restructuring of the three piloted laboratories for specimen culture and sensitivity testing. |

| Characteristics | 2021 | 2023 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | * % | n | * % | |

| Total | 681 | 100 | 777 | 100 |

| Gender | ||||

| Female | 599 | 88 | 619 | 79.7 |

| Male | 82 | 12 | 158 | 20.3 |

| Age | ||||

| <15 | 1 | 0.15 | 0 | 0 |

| 15–44 | 642 | 94.5 | 687 | 88.4 |

| 45–64 | 26 | 3.8 | 72 | 9.3 |

| ≥65 | 10 | 1.5 | 18 | 2.3 |

| Residence | ||||

| Urban | 393 | 57.7 | 546 | 70.3 |

| Rural | 285 | 41.8 | 231 | 29.7 |

| Referred from peripheral health units | ||||

| Yes | 212 | 31.1 | 207 | 26.6 |

| No | 445 | 65.4 | 570 | 73.4 |

| Not recorded | 24 | 3.52 | 0 | 0 |

| Clinical Characteristics | 2021 | 2023 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | * % | n | * % | |

| Co-morbidity | ||||

| Hypertension | 33 | 4.8 | 101 | 12.9 |

| Pre-eclampsia | 41 | 6.02 | 57 | 7.3 |

| Diabetes mellitus (DM) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Smoking | 2 | 0.3 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Alcoholism | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.8 |

| ** Other | 2 | 0.3 | 59 | 7.5 |

| Timing of surgery | ||||

| Morning | 181 | 26.6 | 132 | 17.0 |

| Afternoon | 274 | 40.2 | 378 | 48.6 |

| Evening | 166 | 24.4 | 123 | 15.8 |

| Night | 60 | 8.8 | 129 | 16.6 |

| Not recorded | 0 | 0 | 15 | 1.9 |

| Duration of hospital stay | ||||

| Less than 1 week | 552 | 89.9 | 649 | 83.5 |

| 1 week | 33 | 5.4 | 42 | 5.4 |

| 2 weeks | 4 | 0.6 | 70 | 9.0 |

| 3 weeks | 4 | 0.6 | 7 | 0.9 |

| 4 weeks | 1 | 0.2 | 3 | 0.4 |

| 5 weeks or more | 20 | 3.3 | 5 | 0.6 |

| Not recorded | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0.1 |

| Duration of surgery | ||||

| 1 to 30 min | 165 | 24.2 | 154 | 20.2 |

| 31 to 60 min | 404 | 59.3 | 482 | 63.2 |

| 61 to 90 min | 94 | 13.8 | 116 | 15.2 |

| 91 to 120 min | 10 | 1.5 | 9 | 1.2 |

| >120 min | 7 | 1.0 | 0 | 0 |

| Not recorded | 1 | 0.1 | 0 | 0 |

| Surgeries | 2021 | 2023 | ** p Value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | SSI | * % | n | SSI | * % | ||

| Total | 681 | 46 | 6.7 | 777 | 22 | 2.8 | <0.001 |

| Caesarian section | 599 | 45 | 7.5 | 596 | 15 | 2.5 | <0.001 |

| Herniorrhaphy | 82 | 1 | 1.2 | 181 | 7 | 3.9 | 0.24 |

| Type of Surgical Procedure | Type of Surgery | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caesarean Section | Herniorrhaphy | |||||||||

| 2021 | 2023 | ** p-Value | 2021 | 2023 | ** p Value | |||||

| n | * % | n | * % | n | * % | n | * % | |||

| Elective | 58 | 9.7 | 95 | 15.9 | 0.0012 | 41 | 50.0 | 165 | 91.2 | <0.001 |

| Emergency | 541 | 90.3 | 470 | 78.9 | <0.001 | 41 | 50.0 | 16 | 8.8 | <0.001 |

| Not Recorded | 0 | 0 | 31 | 5.2 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ||

| Total | 599 | 100 | 596 | 100 | 82 | 100 | 181 | 100 | ||

| Choice and Timing of Antibiotics | Type of Surgical Procedure | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Caesarean Section | Herniorrhaphy | |||||||||

| 2021 | 2023 | ** p-Value | 2021 | 2023 | ** p-Value | |||||

| n | * % | n | * % | n | * % | n | * % | |||

| Patients | 599 | 596 | 82 | 181 | ||||||

| Antibiotics | ||||||||||

| Ampicillin | 549 | 92 | 502 | 84.2 | <0.001 | 57 | 70 | 22 | 12.2 | <0.001 |

| Gentamycin | 158 | 26 | 276 | 46.3 | <0.001 | 3 | 4 | 8 | 4.4 | 0.97 |

| Metronidazole | 389 | 65 | 595 | 99 | <0.001 | 75 | 92 | 181 | 100 | <0.001 |

| Ceftriaxone | 121 | 20 | 310 | 52 | <0.001 | 32 | 39 | 174 | 96.1 | <0.001 |

| Amoxicillin | 552 | 92 | 297 | 49.8 | <0.001 | 42 | 51 | 14 | 7.7 | <0.001 |

| Other antibiotics | 33 | 6 | 45 | 7.6 | 0.15 | 15 | 18 | 147 | 81.2 | <0.001 |

| Timing of antibiotics | ||||||||||

| Preoperative only antibiotic | 88 | 14.7 | 2 | 0.3 | <0.001 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Postoperative only antibiotic | 94 | 15.7 | 5 | 0.8 | <0.001 | 24 | 29.3 | 0 | 0 | - |

| Both pre and postoperative antibiotics | 417 | 69.6 | 589 | 98.8 | <0.001 | 58 | 70.7 | 181 | 100 | <0.001 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Kpagoi, S.S.T.K.; Kamara, K.N.; Carshon-Marsh, R.; Delamou, A.; Manzi, M.; Kamara, R.Z.; Moiwo, M.M.; Kamara, M.; Koroma, Z.; Lakoh, S.; et al. Assessing Changes in Surgical Site Infections and Antibiotic Use among Caesarean Section and Herniorrhaphy Patients at a Regional Hospital in Sierra Leone Following Operational Research in 2021. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2023, 8, 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8080385

Kpagoi SSTK, Kamara KN, Carshon-Marsh R, Delamou A, Manzi M, Kamara RZ, Moiwo MM, Kamara M, Koroma Z, Lakoh S, et al. Assessing Changes in Surgical Site Infections and Antibiotic Use among Caesarean Section and Herniorrhaphy Patients at a Regional Hospital in Sierra Leone Following Operational Research in 2021. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease. 2023; 8(8):385. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8080385

Chicago/Turabian StyleKpagoi, Satta Sylvia Theresa Kumba, Kadijatu Nabie Kamara, Ronald Carshon-Marsh, Alexandre Delamou, Marcel Manzi, Rugiatu Z. Kamara, Matilda Mattu Moiwo, Matilda Kamara, Zikan Koroma, Sulaiman Lakoh, and et al. 2023. "Assessing Changes in Surgical Site Infections and Antibiotic Use among Caesarean Section and Herniorrhaphy Patients at a Regional Hospital in Sierra Leone Following Operational Research in 2021" Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease 8, no. 8: 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8080385

APA StyleKpagoi, S. S. T. K., Kamara, K. N., Carshon-Marsh, R., Delamou, A., Manzi, M., Kamara, R. Z., Moiwo, M. M., Kamara, M., Koroma, Z., Lakoh, S., Fofanah, B. D., Kamara, I. F., Kanu, A. B. J., Kenneh, S., Kanu, J. S., Margao, S., & Kamau, E. M. (2023). Assessing Changes in Surgical Site Infections and Antibiotic Use among Caesarean Section and Herniorrhaphy Patients at a Regional Hospital in Sierra Leone Following Operational Research in 2021. Tropical Medicine and Infectious Disease, 8(8), 385. https://doi.org/10.3390/tropicalmed8080385