Abstract

The information really useful to humans must be the trinity of its three components, the form termed syntactic information, the meaning termed semantic information, and the utility termed pragmatic information. But the theory of information set up by Shannon in 1948 is a statistical theory of syntactic information. Thus, the trinity of information theories needs be established as urgently as possible. Such a theory of semantic information will be presented in the paper and it will also be proved that it is the semantic information that is the unique representative of the trinity. This is why the title of the paper is set to “a theory of semantic information” without mentioning the pragmatic information.

1. Introduction

Information has been recognized as one of the major resources that humans could effectively utilize for raising their standards of living in the age of information. The establishment of the theory of information has thus become one of the most urgent demands from the society.

It is well known that the really useful information for humans should be the trinity of its syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic information, so as for the users of the information able to know the form, the meaning, and the utility of the information and thus know how to use it.

Claude E. Shannon published a paper in 1948 in BSTJ titled with “A Mathematical Theory of Communication” [1] that successfully deals with such issues as the calculation of information amount produced by the source of communication system, the calculation of the information capacity of the channel, the coding and decoding for matching the source and the channel, etc., making the great contributions to communication theory. Considering that all the issues are related to information to some extent, the theory was later renamed as Information Theory.

In the case of communication engineering, however, only the form factor of signals (the carrier of syntactic information) needs to consider and nothing to do with both the semantic and pragmatic information. Hence, Shannon theory of information is indeed a statistical theory of syntactic information only, not an entire theory of information at all. This leads the fact that the theories of semantic and pragmatic information get more and more concerns.

In addition to Shannon theory of information, there have also been Combinatory Information Theory and Algorithm Information Theory in academic literate [2,3,4]. But both of them are kinds of theory of syntactic information too and have not considered the theories of semantic and pragmatic information. So we will not mention them any more in the paper.

2. A Brief Review of the Classical Theory of Semantic Information

The earliest effort in attempting the theory of semantic information was made by R. Carnap and Y. Bar-Hillel. The framework of the theory that they proposed in 1950s [5] can very briefly be described as follows, which can also be found from the references [6,7].

First, they defined an ideal language model that contains n (a finite positive number) nouns and k (another finite positive number) adjectives as well as 1 verb “have, or be”. If “a” is a noun and “P” is an adjective, and then “Pa” is read as “a has the property P” or “a is P”. The model has 5 connects:

- ~ (Not): “~Pa” means “a is not P”;

- ∨ (Or): “Pa∨Qb” means “a is P or b is Q”;

- ∧ (and): “Pa∧Qb” means “a is P and b is Q”;

- → (if … then): implication

- ≡ (if and only if): equivalence

Based on the model above, it can produce a number of sentences which may true (Pa∨~Pa, for example), or false (Pa∧~Pa, for instance), or infinitive (Pa, for example) in logic. The amount of semantic information contained in a legal word i is thus defined as a function of the number of sentences in the ideal model of language that the word i can imply. The more the number of sentences that a word can imply in the model of language, the larger the amount of semantic information the word has.

More specifically, a concept called “state descriptor Z” is defined as the conjunction of one noun and one adjective (positive, or negative, but not both). As result, there are kn possible such conjunctions and 2kn possible state descriptions.

Another concept called “range” is set up as follows: The range for a sentence i is defined as a set of the state descriptors in which the sentence i is valid and is denoted by R(i). Further, a measurement function m(Z) is introduced with the following constraints:

- (1)

- For each Z, there is 0 ≤ m(Z) ≤ 1,

- (2)

- For all kn state descriptors, there is ∑m(Z) = 1,

- (3)

- For any non-false sentence i, its m(i) is the sum of all m(Z) within R(i).

The amount of semantic information that sentence i contains is defined as

I (i) = −log2 m(i)

It can be seen from the brief review of the classic theory of semantic information that the concept and measurement here are very much similar to that of Shannon theory of syntactic information. In fact, various kinds of the classic theory of semantic information existed have made most efforts in quantitative measurement of semantic information. Moreover, the basic idea for semantic information measurement of any sentence in classic theory is dependent on the number of sentences in the language model that can be excluded by the sentence.

There are, at least, two demerits existed in the classic theory of semantic information. One is the ideal model of language that is much too far from the natural language in reality and is completely unrealistic model of language. The other demerit is that the theory concerns only with the quantitative measure of the semantic information and yet has no concerns with the essence of semantic information, the meaning factor.

It is very important to point out the major difference between the theories of syntactic and semantic information. The theory of syntactic information needs to take serious concern with the numeric measurement of syntactic information because of the fact that the engineers of communication systems must be able to calculate the precise amount of communication resources consumed, such as the bandwidth of communication channel, the energy of transmission, etc. On the other hand, nevertheless, the most nucleus concern in the theory of semantic information is the meaning contained in the information. This is because of the fact that the users of semantic information should be able to understand the meaning factor of that information so as to be able to effectively use the information for solving problems.

Most of the researchers of classic theory of semantic information had not realized the radical difference between these two kinds of theories pointed out above. The researchers involving in the semantic information studies in later time [8,9,10,11] also did not mention the difference.

3. Fundamental Concepts Related to Semantic Information

The ‘root concepts’ of semantic information are the concept of information and that of semantics. Therefore, it is necessary to make clear the concept of information and that of semantics as well as the relationship between them before doing other things.

3.1. Classic Concepts on Semantics and Information

The classic concept of semantics can be found from the studies on semiotics. Saussure, Peirce, and Morris, among many others, are the major contributors to semiotics.

Saussure proposed a dualistic notion of signs, relating the signifier as the form of the word or phrase uttered, to the signified as the mental concept [12]. Peirce pointed out that a sign is something that stands to somebody for something in some respect or capacity. He considered further that the science of semiotics has three branches: pure grammar, logic proper, and pure rhetoric [13]. More clearly, Morris defined semiotics as grouping the triad syntax, semantics, and pragmatics where syntax studies the interrelation of the signs, without regard to meaning, semantics studies the relation between the signs and the objects to which they apply, and pragmatics studies the relation between the sign system and its user [14].

It is recognized from semiotics that the terms of syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic have been used for expressing the formal features, the meaning, and the utility of the signs with respect to the user of the signs. Interestingly, the three terms form a comprehension for the signs. But semiotics did not give analysis on the mutual relations among the three, as we will do later.

On the other hand, there have been many works concerning the concept of information in history. The most representative ones include the followings:

- --

- N. Wiener announced that [15] information is information, neither matter, nor energy.

- --

- C. Shannon considers that [2] information is what can be used to remove uncertainty.

- --

- G. Bateson [16]: Information is the difference that makes difference.

- --

- V. Bertalanffy wrote that [17] information is a measure of system’s complexity.

More works in this area can be found from the reference [18]. As can be seen, the concept of information is still open. We will have more discussions on the concept in next sub-section.

3.2. Concepts Related to Semantic Information in View of Ecosystem

It is easy to see that the concept of semantic information not only has roots but also has its ecological system. Therefore, the understanding of the concept of semantic information must strictly rely on the understanding of its root concepts and its ecological system. Through the investigation of its root and ecological system, all the constraints that the concept of semantic information should observe could be clear.

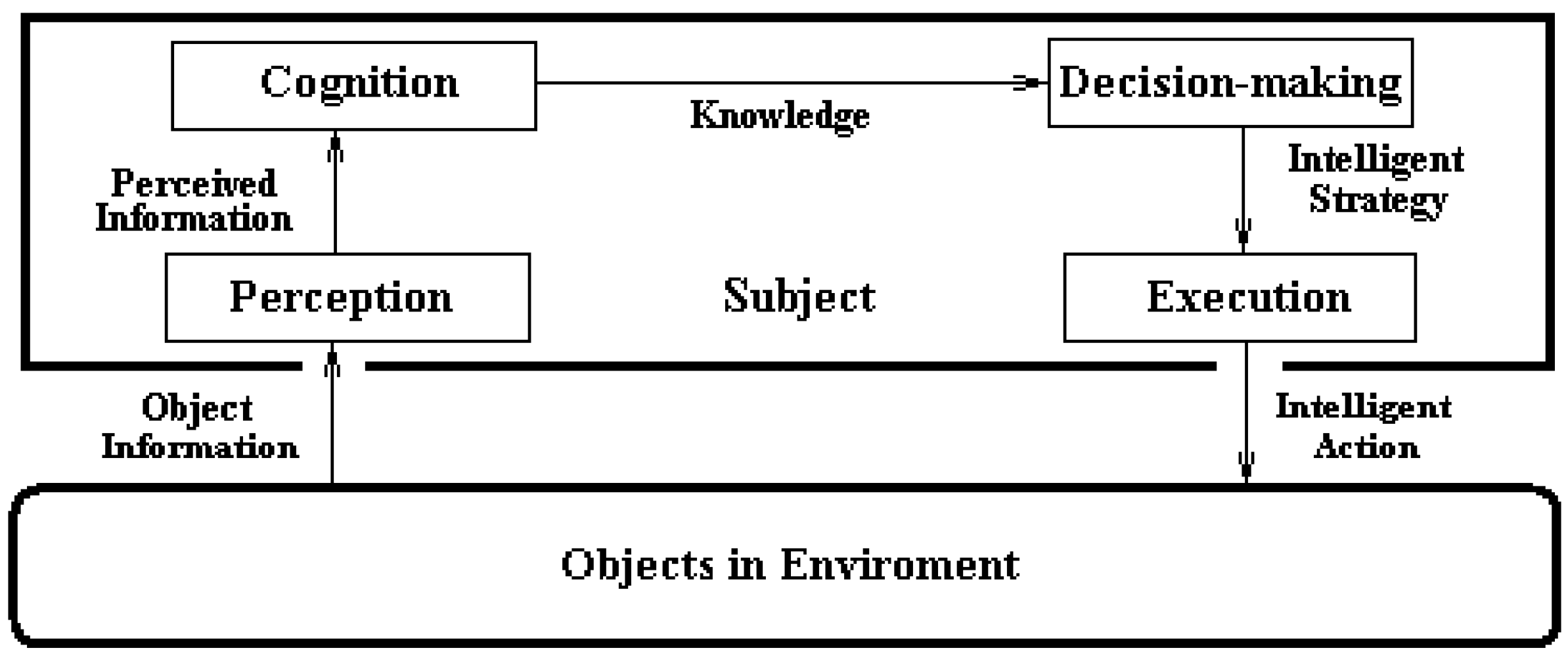

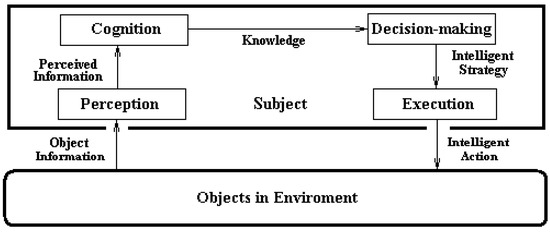

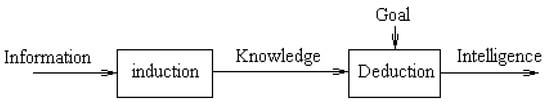

What is the ecological system that semantic information belongs to? As is stated above, the root concept of semantic information is that of information while the ecological system of information is the full process of information-knowledge-intelligence conversion [19], which is shown in Figure 1.

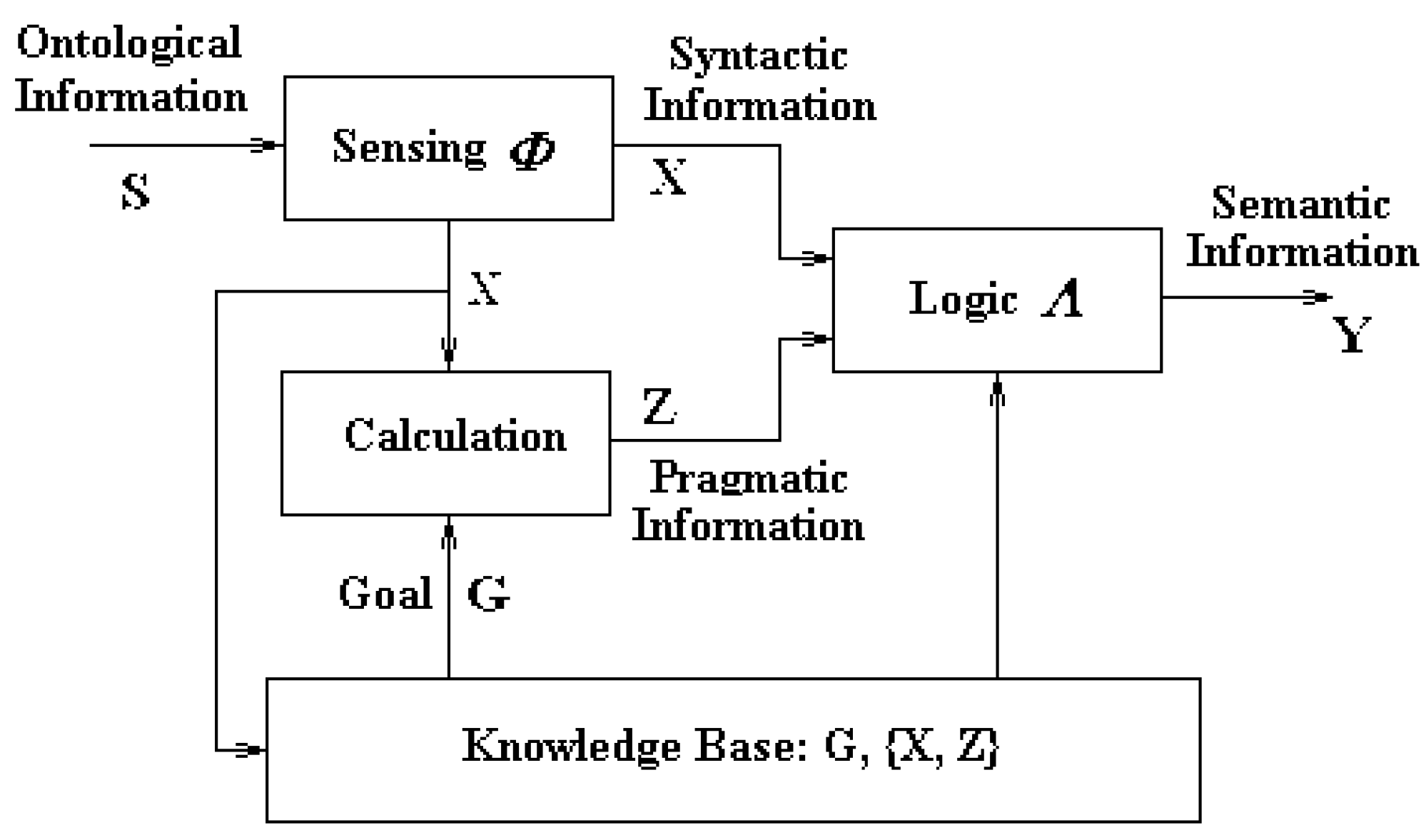

Figure 1.

Model of Information Ecosystem.

In the model of Figure 1, the part at the bottom stands for the object in environment that presents the object information while the part on the top stands for the subject interacting with the object through the following processes: the object information is conversed to perceived one (perception), and the latter is conversed to knowledge (cognition), and further conversed to intelligent strategy (decision-making), and finally conversed to intelligent action (execution) that is applied on the object, forming the basic process of information ecosystem.

The most basic rule the theory of semantic information should observe is that the theory of semantic information must be able to meet with the constraints, or the requirements, imposed from the ecological process of information described above.

It is worth of pointing out that, among all kinds of object information, only those participating in the process of subject-object interaction (see Figure 1) will be regarded as meaningful and will therefore be carefully studied. Others having not entered into the subject-object interaction will, naturally and thus reasonably, be neglected by the subject. In other words, the model of information ecosystem shown in Figure 1 is typical, necessary, and sufficient.

It is indicated from the model in Figure 1 that the most significant value that information could provide to humans (and human society) is not merely information itself, but even more its ecological products, the knowledge and intelligence. This is because of the fact that information itself is phenomenon about something that can tell “what it is” while knowledge is the essence about some things that can tell “why it is so” and the intelligence is the strategy for dealing with something that can tell “how to do it”.

So, it is not wise in any cases if one concerns only with information itself without paying attentions to knowledge and intelligence. In other words, one who studies information should not stop at the level of information but should continue to do the study with the view of ecological process of information. This is an important understanding for information studies.

Now let us start to have a specific investigation on all the concepts related to the one of semantic information along with the line of ecological system of information shown in Figure 1.

Definition 1 (Object Information/Ontological Information).

The object information concerning an object is defined as “the set of states at which the object may stay and the pattern with which the states vary” presented by the object itself.

The term “ontological information” is also adopted for “object information” because this information is only determined by the object and has nothing to do with the subject. The two names, object information and ontological information, are mutually equivalent but the term of “object information” will more frequently be used in the paper.

Referring back to Definition 1, the argument of object information can briefly be expressed as the “states-pattern”. For example, given an object whose possible set of states is X and the pattern with which the states vary is P, the corresponding object information can briefly be represented as {X, P}.

Definition 2 (Perceived Information/Epistemological Information).

The perceived information a subject possesses about an object, which is also termed as epistemological information, is defined as the trinity of the form (named the syntactic information), the meaning (the semantic information), and the utility (the pragmatic information), all of which are perceived by the subject from the object information.

The term “epistemological information” is adopted because of the fact that this information is determined not only by the factors of object (the “states-pattern”), but also by the factors of the subject (the subject’s knowledge and goal).

It is very clear by comparing Definitions 1 and 2 that the object information is the real source coming from the real world while the perceived information is the product of the object information via subject’s perception. As result, the perceived information should contain more abundant intensions than the object information does.

Note that the concept of “semantic information” has been defined in Definition 2, which is the meaning the subject perceived from the object information. Note that the term of semantic information here is well matched with that of semantics in semiotics.

Definition 3 (Comprehensive Information).

The trinity of syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic information is named comprehensive one.

So, the concept of “perceived information”, or of “epistemological information”, declares that it has three components: syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic information whereas the trinity of the three is specially named the “comprehensive information”.

Noted that although the concepts of syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic have been defined in semiotics, the mutual relationship among them has never been studied. As we can see later, the mutual relationship among them is the most important issues in information studies.

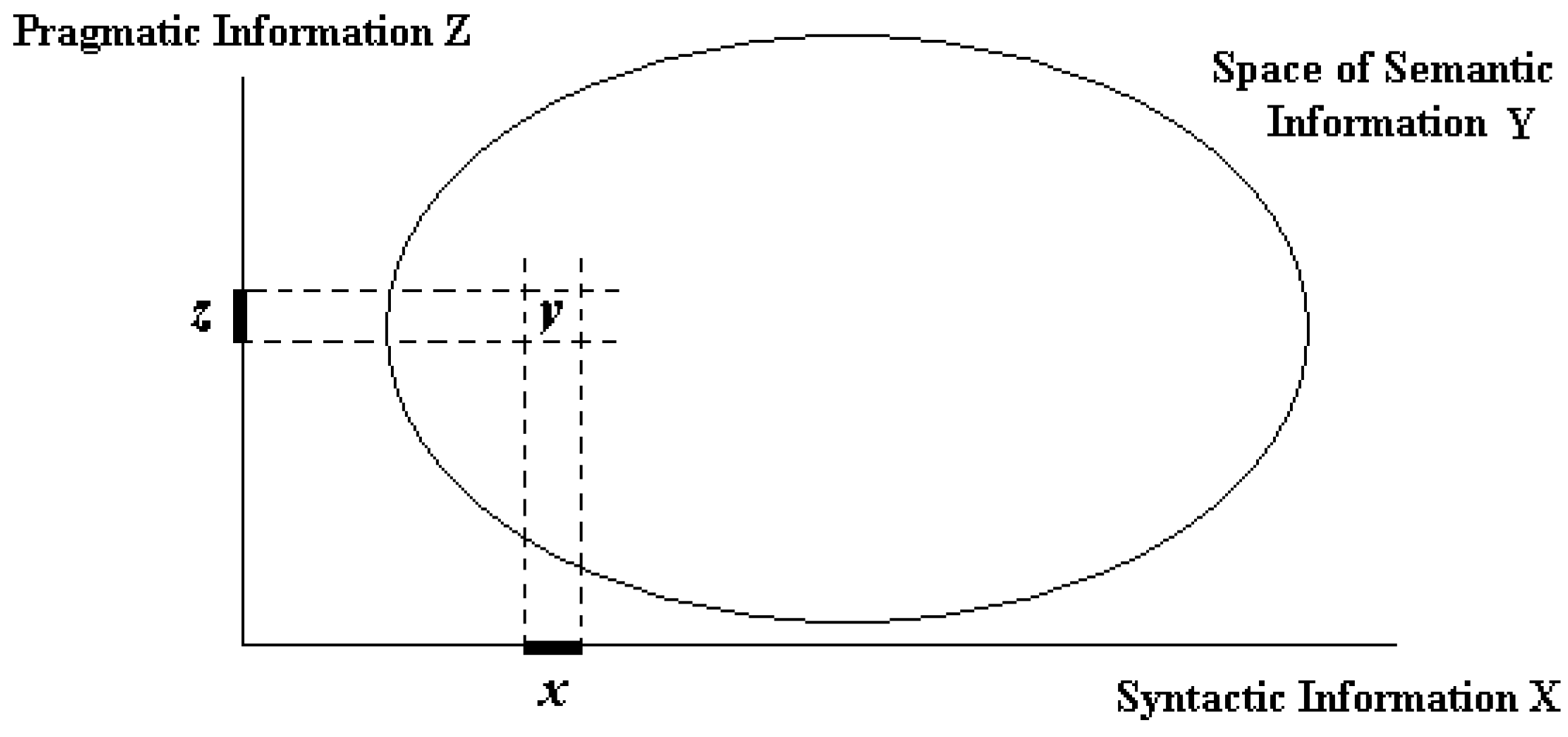

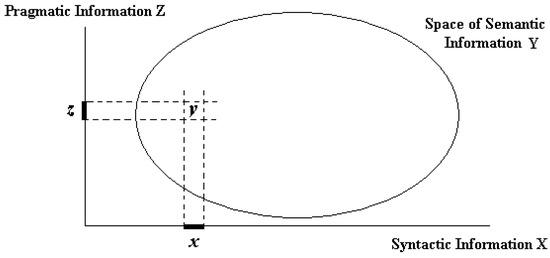

Definition 4 (Mutual Relation among Syntactic, Semantic, and Pragmatic Information).

The syntactic information is specific in nature and can directly be produced through subject’s sensing function while the pragmatic information is also specific in nature and can directly be produced through subject’s experiencing. However, the semantic information is abstract in nature and thus cannot be produced via subject’s sensing organs and experiencing directly. The semantic information can only be produced based on both syntactic and pragmatic information just produced already, that is, by mapping the joint of syntactic and pragmatic information into the semantic information space and then naming it.

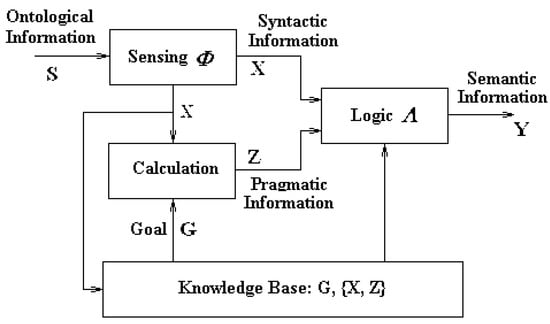

Further, the mutual relationship of the semantic information to the syntactic and pragmatic information can be expressed in Figure 2. Note that this will be explained more clearly via Figure 2 in Section 4.1.

Figure 2.

Relation of semantic information to syntactic and Pragmatic information.

It is concluded from the discussions above that the semantic information can serve as the legal representative of the perceived information. This is why the semantic information possesses the highest importance compared with the syntactic and pragmatic information.

Compared with all definitions and discussions given above, we can conclude:

- (1)

- The object/ontological information defined in Definition 1, the “states-pattern presented by object”, is neither matter nor energy and is thus in agreement with Wiener’s statement. However, the Definition 1 is more standardized than the statement.

- (2)

- The concept of perceived/epistemological information defined in Definition 2 is just what can be used to remove the uncertainties concerning the “states-pattern”. It is easy to see that the concept of information in Shannon theory is the statistically syntactic information, only one component of the perceived information. So, the Definition 2 is more reasonable and more complete than Shannon’s understanding is.

- (3)

- As for the Bateson’s statement, it is pointed out that the most fundamental “difference” among objects is their own “states-pattern” presented by the objects. Hence, the Definition 1 and Bateson’s statement is equivalent to each other. But Definition 1 is more regular.

- (4)

- Bertalanffy regarded information as “complexity of system”, in fact the complexity of a system is just the complexity of its “states-pattern” presented.

All in all, the Definitions 1 and 2 enjoy the advantages of more regular, more standardized, more reasonable, more universal, and more scientific compared with the statements given by Wiener, Shannon, Bateson, Bertalaffy, and others. So, we would like to use the Definitions 1 and 2 for defining object/ontological information and perceived/epistemological information.

Up to the present, the concept of semantic information has been well defined. According to the view of information ecology, however, the discussion on fundamental concepts cannot be stop here. It is necessary to investigate how the later processes of information ecology (see Figure 1) may exert influence and impose constraints on semantic information.

Definition 5 (Knowledge).

Knowledge that subjects have possessed in their minds concerning certain class of events is defined as the “set of states at which the class of events may stay and the common rule with which the states vary” that have been summed up from a sufficiently large set of samples of perceived information related to the class of events.

For brevity, knowledge can be described by using the phrase of “states-rule” just as perceived information is described by using the phrase of “states-pattern”.

Since knowledge is the products abstracted from perceived information, knowledge also has its own three components: formal, content, and value knowledge respectively corresponding to syntactic information, semantic information, and pragmatic information. Similar to the case of perceived information, the content knowledge can serve as the legal representative of the entire knowledge. It is obvious that semantic information plays a fundamental role in the studies of knowledge theory.

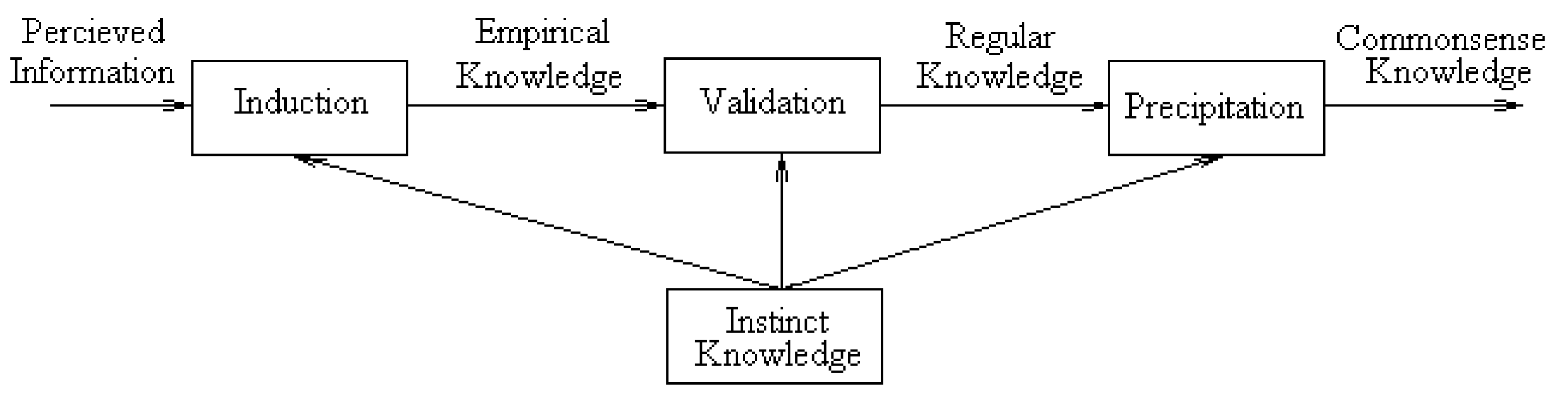

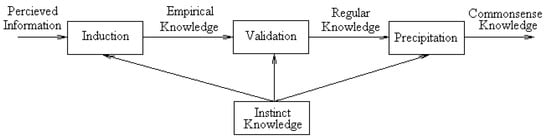

It is necessary to note that knowledge itself forms an ecological process: from the perceived information to the empirical knowledge via the process of induction, and then to the regular knowledge via the process of validation, and further to the commonsense knowledge via the process of precipitation, all based on the instinct knowledge. This is shown in Figure 3 and is called the internal chain of knowledge ecology.

Figure 3.

Internal Chain of Knowledge Ecology.

It is easy to understand that the empirical knowledge is the knowledge in under-matured status, the regular knowledge is the one in the normal-matured status, and the commonsense knowledge is the one in the over-matured status. As is well accepted, from the under-matured status to the normal-matured status and further to the over-matured status, this is a typical ecological process.

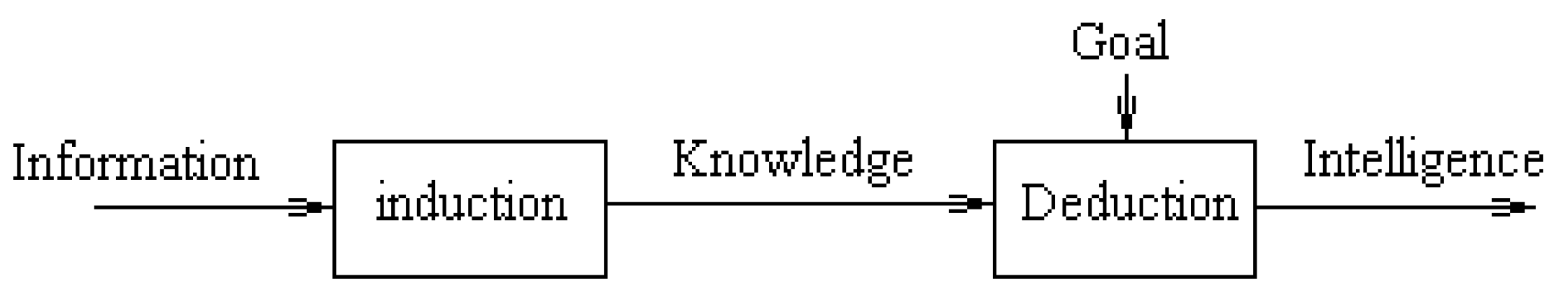

On the other hand, there is an external chain of knowledge ecology that is from (perceived) information to knowledge via inductive operations and then from (perceived information and) knowledge to intelligence via deductive operations under the guidance of the system’s goal as is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

External Chain of Knowledge Ecology.

The internal chain and external chain of knowledge ecology, as well as the definition of semantic information (which is the representative of perceived information), are of great significance in the studies of artificial intelligence that will be seen in later stage of the paper.

Definition 6 (Human Wisdom).

Human wisdom is the special ability only for humans. It is the ability for humans to discover, to define, and to solve the problem faced in environment by using his knowledge and his goal for better life. When the old problem is solved, the new problem will be discovered, defined and solved. By virtual of this ability, the living standards for human kinds and the human ability itself are continuously improved and strengthened [20].

It is clear from the Definition 6 that human wisdom is consisted of two interactive parts: (1) the ability to discover and to define the problem that must be solved for better living, which is termed as the implicit wisdom; and (2) the ability to solve the problem that has been defined by implicit wisdom, which is named as the explicit wisdom.

The ability of implicit wisdom is supported by such mysterious factors as the subject’s goal for better living, the subject’s knowledge for problem solving, subject’s intuition, imagination, inspiration, and aesthetics, and the like whereas the ability of explicit wisdom is supported by such kinds of operational ability as information acquiring, information processing, information understanding, reasoning, and execution. Because of the difference between the implicit and the explicit wisdom, it is possible to understand and simulate the explicit wisdom on machines while extremely difficult, if not impossible, to understand and simulate the implicit wisdom on machines.

Definition 7 (Human Intelligence).

The human explicit wisdom is particularly named as human intelligence that is obviously the subset of human wisdom.

Definition 8 (Artificial Intelligence).

The man-designed intelligence in machines inspired from human intelligence (explicit human wisdom) is named as artificial intelligence that is evidently relies on the knowledge and therefore heavily relies on semantic information.

It is easy to know that there is very closed links between artificial intelligence and human wisdom (see the Definitions 6–8) on one hand and there is also great difference between them on the other hand. As for the working performance like working speed, working precision, and strength of working load, etc., artificial intelligence may be much superior than human wisdom. However, as for the creative power is concerned, artificial intelligence can never compete with human wisdom because of the fact that machines are not living beings, they do not have their own goals for living, and thus do not have the ability to discover and to define the problems for solving.

Till now we could have the following conclusions drawn from the discussions carried above:

- (1)

- Semantic information is the result of mapping the joint of syntactic and pragmatic information into the space of semantic information and naming.

- (2)

- Semantic information is the legal representative of perceived/comprehensive information.

- (3)

- Semantic information plays very important role in knowledge and intelligence research.

4. Nucleus of Semantic Information Theory

As the necessary foundation of semantic information theory, the concepts related to semantic information have been thoroughly analyzed in Section 3. In the following section of the paper, the generative theory, the representation and measurement theory, and the applications of semantic information will all be discussed successively [20].

4.1. Semantic Information Genesis

Referring back to Definition 2, we realize that syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic information are three components of the perceived information, which is perceived by the subject from the object information related. So, object information is the real source of semantic information.

Looking back to Definition 4, we understand that, different from the syntactic and pragmatic information that both of them are specific in nature and thus can directly be produced via subject’s sensing functions or experiencing function whereas semantic information is abstract in nature and thus cannot directly be produced via subject’s sensing and experiencing functions. Semantic information is a concept produced by subject’s abstract function.

Based on the Definitions 2 and 4, the model for semantic information generation process can then be implemented as follows (see Figure 4 below).

First, let the object information be denoted by S while syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic information by X, Y, and Z respectively. And then we assume that there is a comprehensive knowledge base (representing the subject’s memory system) that has already stored a great set of pairwise knowledge: {Xn, Zn}, n = 1, 2, …, N, where N is a very large positive integer number. In word expression, this means that the n-th syntactic information has the n-th pragmatic information associated with it. In other words, the subject has had abundance of a priori knowledge: what kind of syntactic information will have what kind of pragmatic information. Xn and Zn, n = 1, 2, …, N, are one-to-one correspondingly.

The specific process for generating Y from S can be described in the following steps as is shown in Figure 5 below.

Figure 5.

Model for Semantic Information Generation.

- step 1

- Generating X from S via Sensing Function

- Mathematically, this is the mapping function from S to X.

- This function can be realized via sensing organs for humans.

- It can also be implemented via sensor systems for machine.

- step 2-1

- Generating Z from X via Retrieval Operation

- Using X, the just produced syntactic information in step 1, as the key word to search the set {Xn, Zn} in knowledge base for finding the Xn that is matched with X. If such an Xn is found, the Zn corresponding to Xn in {Xn, Zn} is accepted as the pragmatic information Z.

- This operation can be realized via recalling/memorizing function for humans. It can also be implemented via information retrieval system for machine.

- step 2-2

- Generating Z from X via Calculation Function

- If the Xn matching with X cannot be found from {Xn, Zn}, this means that the system is facing a new object never seen before. In this case, the pragmatic information can be obtained via calculating the correlation between X and G, the system’s goal:Z ~ Cor. (X, G)

- This function can be performed via utility evaluation for humans.

- It can also be implemented via calculation for machine.

- step 3

- Generating Y from X and Z via Mapping and Naming

- Map (X, Z) into the space of semantic information and name the result:Y = λ (X, Z)

- This function can be performed via abstract and naming for humans.

- It can also be implemented via mapping and naming for machine.

It is evident that both the model in Figure 5 and the steps 1–3 clearly describe the principle and the processes for semantic information (with the accompanied syntactic as well as pragmatic information) generation from the object (ontological) information via the system’s functions of mapping, retrieving (recalling), calculation (evaluation) and mapping and naming. All of the functions are theoretically valid while technically effective and feasible.

The Equation (2) can also be expressed as

where X, Y, and Z stand respectively for the spaces of syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic information and λ the operations of mapping and naming.

y = λ (x, z), x∈X, y∈Y, z∈Z,

The correctness of Equation (2), or Equation (3), can also be illustrated by a number of practical examples in reality.

Suppose a piece of syntactic information (the letter sequence) is given, the corresponding semantic information (y = meaning of the letter sequence) will then depend only on z, the pragmatic information associated according to Equation (3). For instance, given that x = apple, then y will be different, depending on different z:

- If {x = apple, z = nutritious}, then y = fruit.

- If {x = apple, z = useful for information processing}, then y = i-pad computer.

- If {x = apple, z = information processor in pocket}, then y = i-phone.

The model in Figure 5 and the Equations (2) and (3) have identified that the concept of semantic information stated in Definition 2 and the mutual interrelationship among syntactic, semantic, and pragmatic information described in Definitions 4 are appropriate and legitimate. It is also identified that semantic information so defined can practically be generated either by human subjects, or by intelligent systems.

From now on, we use semantic information to represent the comprehensive/epistemological information, or perceived information.

4.2. The Representation and Measurement of Semantic Information

As is emphasized above that, different from Shannon theory of information (as a statistically syntactic information theory) where the measurement of information is the most concerned issue, here in the case of semantic information theory the most concerned issue is generally not its quantitative measurement but is its qualitative assessment—its ability to understand the meaning of the information and the ability in logic reasoning based on the meaning. The quantitative measurement is in the second place in semantic information theory.

Yet, no matter for quantitative measurement or for qualitative assessment, the representation of semantic information is a common need and an unavoidable foundation. Hence, the first issue before any others we need to discuss is the one of semantic information representation.

4.2.1. Representation of Semantic Information

Suppose we have a piece of semantic information y∈Y, which may be a word, a phrase or a sentence, even a paragraph of voice, or video, it can be represented by an N-dimensional vector, where N is a finite and positive integer:

y = {yn|n = 1, 2, …, N},

If N = 1, y is the semantic information with a single element and is named atomic semantic information, the minimum unit of semantic information which can be judged as true or false, meaning that whether the corresponding syntactic information xn is really associated with the pragmatic information zn? If N > 1, y is named the composite semantic information.

For atomic semantic information yn, it can be expressed by using the following parameters: its logic meaning yn and its logic truth tn, where yn can be defined by Equation (3) while tn can be defined by

0 ≤ tn ≤ 1, n = 1, 2, …, N

It is clear that the parameter is a kind of fuzzy quantity [21]:

1, true

tn = {a∈(0, 1), fuzzy

0, false

Thus, for atomic semantic information yn, n = 1, 2, …, N, the comprehensive expression is

where, yn is determined by Equation (3) and tn by Equations (2) and (3).

(yn; tn), n = 1, 2, …, N

For N-dimensional semantic information vector y, its truth vector is expressed as

t = {tn| n = 1, 2, …, N}

Correspondingly, its comprehensive expression is

{yn, tn| n = 1, …, N}

4.2.2. Measurement of Semantic Information

Generally speaking, the quantitative measurement of semantic information is not as important issue as that in syntactic information theory. So this sub-section is treated in appendix.

5. Concluding Remarks

The most fundamental purpose for humans to acquire information is to utilize information for solving the problems they are facing. For this purpose, to understand the meaning of the information (semantic information), to evaluate the real value of the information (pragmatic information), and thus to create the strategy for solving the problem are absolutely necessary. However, the unique theory established so far is the mathematical theory of communication by Shannon in 1948, which is a statistical theory of syntactic information and has nothing to do with the theory of semantic and pragmatic information.

Having believed the truth that it should not be acceptable for humans to live in such a world that it has only form factors while has no meaning and no value factors, the author of the paper have made efforts to analyze the difficulties and setbacks that former researchers have encountered, and to investigate the methodologies suitable for information studies and then discovered the new one, which can be termed “methodology of ecological evolution in information discipline”, or more briefly, the methodology of information ecology.

Based on the methodology of information ecology, the concepts related to information and semantic information have been re-examined, the definitions of object information and perceived information have been re-clarified, the interrelationship among the syntactic, semantic and pragmatic information and the principle of genesis of semantic information have been discovered, the representation and measurement of semantic information have been set up, and the important applications of semantic information in the fields of knowledge expression and organizing (knowledge base architecture), learning, understanding, cognition, and strategy creation have been re-explored, and the framework of semantic information theory has been formulated.

On the other hand, there are still some open issues existed. One is the better approach to the quantitative measurement of semantic information. The other is the logic theory needed for supporting the inference based on semantic information. The current theory of mathematic logic is not sufficient and the new and more powerful theory of logic, universal logic and the dialectic logic for instance, are eagerly expected.

Acknowledgments

The studies on semantic information theory presented here have gained the financial support from the China National Natural Science Foundation. The author would like to express his sincere thanks to this foundation.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Note on the Measurement of Semantic Information

In some cases people may concern such kind of problems as how many amount of semantic information is provided, or which one provides more amount of semantic information between two pieces of semantic information?

Evidently, the amount of a piece of semantic information would be closely related to its logic truth. For example, given an atomic semantic information yn, the semantic information amount it provides would be minimum if tn = 0 whereas be maximum if tn = 1. The parameter tn is a fuzzy quantity as was pointed out above. According to [18], the normalized amount of the atomic semantic information can be calculated by

I(yn) = log22 + [tnlog2(tn) + (1 − tn)log(1 − tn)]

In which

is assumed. The unit of semantic information amount is also “bit”. It is easy to calculate from Equation (7) that I(yn) = 1, if tn = 1; I(yn) = −1, if tn = 0; I(yn) = 0, if tn = 1/2; I(yn) > 0, if 1/2 < tn < 1; I(yn) < 0, if 0 < tn < 1/2.

0log20 = 0

For N-dimensional semantic information vector y, we generally have

where f is a complex function whose form depends on the specific logic relation among the atomic semantic information yn.

I(y) = f{I(yn), n = 1, 2, …, N}

In one extreme case where the logic relation among the N pieces of atomic semantic information yn in y is independent to each other, we have

I(y) = ∑I(yn)

In another case where N pieces atomic semantic information yn are strictly related to each other, we will have

I(y) = ∏I(yn)

The Equations (7)–(10) are acceptable but not necessary optimal though.

References

- Shannon, C.E. A Mathematical Theory of Communication. BSTJ 1948, 47, 379–423; 632–656. [Google Scholar]

- Kolmogorov, A.N. Three Approaches to the Quantitative Definition of Information. Int. J. Comput. Mach. 1968, 2, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kolmogorov, A.N. Logic Basis for Information Theory and Probability Theory. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 1968, 14, 662–664. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaitin, G.J. Algorithmic Information Theory; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Carnap, R.; Bar-Hillel, Y. Semantic Information. Br. J. Philos. Sci. 1953, 4, 147–157. [Google Scholar]

- Brilluion, A. Science and Information Theory; Academic Press: New York, NY, USA, 1956. [Google Scholar]

- Bar-Hillel, Y. Language and Information; Reading, MA, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Millikan, R.G. Varieties of Meaning; MIT Press: Cambridge, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Stonier, J. Informational Content: A Problem of Definition. J. Philos. 1966, 63, 201–211. [Google Scholar]

- Gottinger, H.W. Qualitative Information and Comparative Informativeness. Kybernetik 1973, 13, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Floridi, L. The Philosophy of Information; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- De Saussure, F. Course in General Linguistics; Ryan, M., Rivkin, J., Eds.; Blackwell Publishers: Oxford, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Peirce, C.S. Collect Papers: Volume V. Pragmatism and Pragmaticism; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1934. [Google Scholar]

- Morris, C.W. Writings on the General Theory of Signs; Mouton: The Hague, The Netherlands, 1971. [Google Scholar]

- Wiener, N. Cybernetics; John-Wiley and Sons: New York, NY, USA, 1948. [Google Scholar]

- Bateson, G. Steps towards an Ecology of Mind; Jason Aronson Inc.: Lanham, MD, USA, 1972. [Google Scholar]

- Bertalanffy, L.V. General System Theory; George Braziller Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong Y, X. Principles of Information Science; Beijing University of Posts and Telecommunications Press: Beijing, China, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.X. Information Conversion: The integrative Theory of Information, Knowledge, and intelligence. Sci. Bull. 2013, 85, 1300–1306. [Google Scholar]

- Zhong, Y.X. Principles of Advanced Artificial Intelligence; Science Press: Beijing, China, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zadeh, L.A. Fuzzy Sets Theory. Inf. Control 1965, 8, 338–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).