1. Introduction

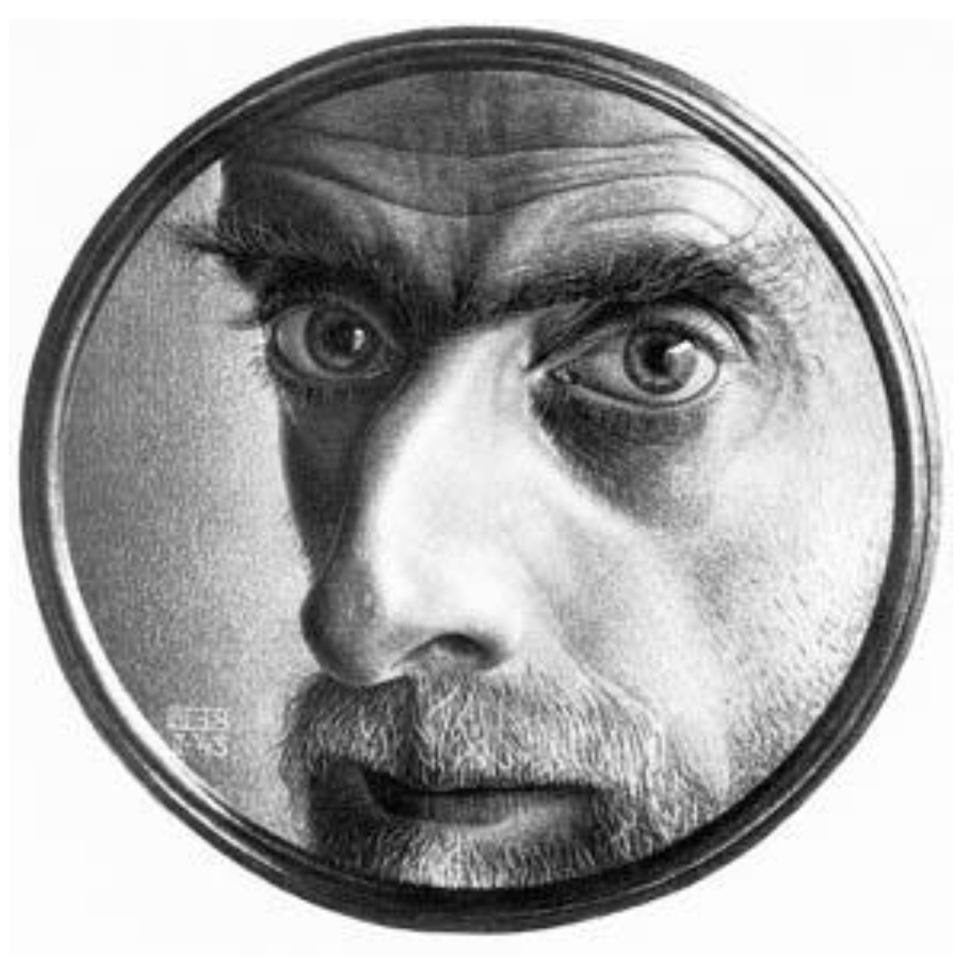

Few draftsmen, among the graphic artists of the twentieth century, may appear as distant as Maurits Cornelis Escher (

Figure 1) and Saul Steinberg (

Figure 2). Steinberg has built his own career as a humorist, developing, since years of collaboration with the Milanese magazine

Il Bertoldo, to the mature works on

New Yorker’s pages, a caustic, fulminant, sometimes even moving spirit. Escher, devoted to a lonely and coherent search work on certain precise themes—from the regular division of the plane to the anamorphosis–, was perceived as “the absurd draftsmen”, appreciated by mathematicians and crystallographers for the precision with which, by applying complex geometric principles, has managed to shape the images that are often described paradoxically and imaginatively. If Steinberg with a few strokes represents a varied humanity on which his glossy, compassionate and penetrating look is laid, Escher barely fills his fantastic spaces with rigid, impersonal, distant figures. If Steinberg’s drawings look fresh, extemporary, and light, Escher’s work, finely defined in a technical sense, seems to be supported—and sometimes burdened—by some kind of expressive solemnity.

In addition to some similar biographical paths, especially during the first part of their life, - both of them had settled in Italy where they could devote themselves to the design of the cities and where they had been otherwise victims of the intrusiveness of the Fascist regime [

1,

2,

3]—although in all likelihood they have never met in person; however, there are some strong, non-superficial affinities between the two authors to which it is worth devoting. While investigating different subjects with very different modes, techniques and spirit, the attitude towards the fundamental themes of representation is similar.

2. Hands and Stairs

The bizarre coincidence has already been pointed out [

4,

5,

6,

7], that a Steinberg drawing (

Figure 3) [

8], placed at the margins of a page of his volume

The Passport (1954), clearly recalls an Escher lithography (

Figure 4),

Drawing Hands (1948). Escher himself, in an interview [

9], was amazed by this correspondence. In both images, two hands hold a stylus. Each hand draws the other and it just seems that they act at the same time. The two images are then frozen in a sort of circular paradox: each hand is together ‘cause’ and ‘effect’, object of drawing and active subject. There is no beginning or end in the action that is represented; the observer is involved in a narration of time free from the common categories: the perpetual development of the action represented makes it impossible to see a beginning and a fulfillment.

However, apart from the content of the representation, the similarities leave room for the profound differences between the two works. Escher’s image is a lithography, a complex print obtained by elaborating wisely the density of the pencils on the lithographic stone. At the end of the 1940s, Escher had already achieved a remarkable ability to control this complex graphic technique and had been able to give his prints a remarkable softness, reaching often persuasive effects of likelihood. Steinberg proceeded in the opposite direction. While caressing the idea of dedicating himself to painting, he was making his stroke more and more dry and synthetic, sometimes reaching full parts of the drawing, and alluding to shapes, objects, elements that were just evoked on the sheet. These two different graphic languages translate the opposing attitudes of the two authors immediately clear to the observer. Where Escher’s work astonishes and disorientes, Steinberg’s drawings promptly communicate a sense of empathy, often arousing a smile.

Even so, moving on so different registers, as has been said, the research of the two artists since the first years of activity, for some substantial aspects, seems to proceed in the same direction. Steinberg, since the early publications in the mid-forties [

10], had characterized his research by animating pages with human figures that, holding a pen or pencil, traced the same lines as describing their silhouette, with clocks that disappear with the passing of hours from the motion of the hands, with absurd road signs in which the form opposes the contents of the message. Escher, on his own, at the beginning of the 1950s had drawn worlds where physical laws apply simultaneously in different (sometimes even opposing) ways, in which the figures and backgrounds swap their roles inverting unpredictably, explored imaginary places governed by extravagant space reality, describing them in a seemingly coherent way.

Among the other direct similarities between the works of the two authors, one stands out among the drawing of a paradoxical stair (of closed annular form) in which, depending on the direction of travel, you are going up or down. If the stair of Escher (

Klimmen en Dalen, 1960) (

Figure 5) uses an optical illusion to firmly construct the visual paradox, Steinberg’s one (

Figure 6) [

11] shows an impossible structure to be physically but coherently from the formal point of view, in which downhill and climb alternate.

3. Common Topics

It would be interesting to study the unbounded corpus of the works of Escher and Steinberg in the search for punctual correspondences and analogies between the images, but unfortunately this task goes beyond the scope of these notes. Rather than pointing at the direct similarities between pairs of works, in these pages, more modestly—far from believing that the authors have inspired each other or that their works have common references—it will be better be shown how, inside of the two different researches, there are some amazing affinities on certain themes about representation that probably arise from the same concern about the relationship between reality and its description that permeated part of Western thought in the twentieth century. During their career, each of them deepened—first by building, then refining their own language—similar themes that deal with the very way of conceiving the representation and the production of images.

Both, for example, have dealt with the theme of metamorphosis. Escher explores it in his own work—made on narrow paper strips a few feet long to suggest a diachronic-oriented image reading, as if it were a text—simple elements, usually squares, subjected to continuous variation of the shape, altered in an almost imperceptible manner at every single passage (

Figure 7). In this way he manages to build a stripe in which insects, birds, cubes, urban landscapes continually blend into intermittent, hybrid, difficult to interpret patterns, whose shape quickly crises our ability to give precise meaning to the figures.

Steinberg, too, in dealing with the same theme, draws on his vivid description of situations and human vicissitudes on a markedly elongated size sheet, suggesting also an orderly and oriented image reading. His story (

Figure 8) takes place around a continuous horizontal line that, depending on the elements that are being approached, turns from time to time in horizon, rope to stretch the linen, edge of a table, rail bridge, limit of a ceiling, separation between marine waters and the atmosphere, forcing the observer to continually update his reading of the signs and showing, in this case, the fragile precariousness of our interpretative categories.

One of Escher’s dearer themes is the relationship between the figures and the background within the same image. Ever since his second trip to Spain in 1935, he was deeply hit by the Alhambra mosaic tassels that portray abstract geometric designs in which a similar shape can tap the floor with contrasting color elements. After carefully studying these figures he devoted great passion to a study on the regular division of the plane and produced hundreds of drawings in which animals, human figures, abstract shapes perfectly fit on the plane (

Figure 9) [

12]. Many of these works became basic materials for more complex works such as

Day and Night (

Figure 10), where not only two flocks of ducks flying in different directions fit into perfection but at the bottom of the image the forms of birds changes in the form of fields in the background.

Steinberg, on the other hand, faces the same theme by focusing his attention on the contour line between the different elements, as can be seen in the drawing representing the dancing couple (

Figure 11) or in the one with a man sitting in armchair (

Figure 12), both published on

The Passport. In drawing the contour between things, sometimes even with a closed line, Steinberg does not isolate the figures, some of which lie on the line between the completeness of the description and belong to the indistinct field of the white background. In this way the shape of the leg belongs to the same pattern as the pillow that makes it the background, the body is described by the lines that define the armchair and the face can be composed of features that ‘float’ on the sheet field.

Another common theme for the two authors—immanent at the same statute of graphic representation—is that of ambiguity between two and three-dimensional elements. Escher has often made drawings, representing images where the content was of two-dimensional nature. In a color lithograph (

Reptiles, 1943), a flat floor tile is depicted with images of small saurians that, coming out of the sheet and acquiring three-dimensional solidity, make a round of some objects on a table before returning to compose the mosaic on the sheet (

Figure 13). Likewise, in

Three Spheres of 1945, ambiguously represents a solid sphere and two other images of the same sphere that are the perspective representation of two-dimensional elements. In a rather different way, Steinberg has populated social gathering places, such as a living room during a party, with bizarre human figures that are basically flat, with no thickness, consisting of purely two-dimensional silhouettes (

Figure 14).

Similarly, Escher and Steinberg deal with the theme of the ambiguous relationship between the space of the picture displayed in an art gallery and the very space of the exhibition, in other words the relationship that can be established between what is inside and outside of the picture. Escher builds an image of an exhibition of his works with a child viewer seen from behind (

Print Gallery, 1956,

Figure 15). Among the exhibited works, however, there is a picture representing the same art gallery that in this way becomes, in a kind of circular loop, the contents of the picture and container of the same. Steinberg with different tools represents the same ambiguity by showing spectators so focused to admire the paintings to become part of, finding themselves at the same time inside and outside the work, in the container space, and in the works contained therein (

Figure 16). The study of other themes—such as that of reflection and mirror—would show other correspondence between the work of two authors.

4. Magritte

The fact that Escher and Steinberg—the one primarily admired by science-loving men and scientists, the other essentially as a cartoonist–had not–and yet do not–have a clear place in the world of contemporary art, kept the two authors away from sharp forms of identification of their works within the artistic currents of the twentieth century. Most of them were ignored by art historians who would probably have difficulty referring to some specific “current”. Although it is certainly more prudent to leave this state unaltered, trying not to suggest rigid reference patterns, it might be useful to couple some of their works to some of the themes developed within the surrealist movement, especially Magritte [

13].

Steinberg—it must be emphasized—often formulated apodictic judgments against surrealism and some of its exponents. In 1945 he wrote to Aldo Buzzi: “Ho visto una mostra di Dalì oggi. È un pirata furbo che truffa i compratori e se lo meritano” [

2] (p. 20) or about the possibility of filming photographs of drawings: “La difficoltà è di evitare di cadere nel surrealismo” [

2] (p. 36). Always reflecting with Buzzi in 1975 about some books, he writes: “Leggo in questi giorni il libro della Elsa Morante buono delle volte, anche uno del tedesco Böll, buono al principio, illegibile dopo cento pagine per la trappola del surrealismo in cui cascano questi Europei che hanno perso qualche anno di evoluzione sotto il fascismo” [

2] (p. 88), or about some films: “Visto

Apocalypse Now peccato, sprecato. Il surrealismo è un’influenza orribile” [

2] (p. 109).

The tenor of judgments radically changes when he speaks of René Magritte and his work: “Certe sue cose mi piacevano, ma in genere pensavo che lavorava troppo di pittura per spiegare una barzelletta. Ma questo era il suo vero talento, o meglio la sua vera scoperta di milite fedele del surrealismo: lavorare con la stessa meticolosità e passione che gli amanuensi impiegavano nel miniare i codici” [

3] (p. 48). Still, Steinberg had a work by Magritte that represents a double portrait of André Breton, whom he himself describes in a careful and affectionate way.

Escher liked Magritte too, for whom he had a real passion, and the mathematician Bruno Ernst, a friend and biographer, used Magritte’s work in a proper and effective manner to frame some of the themes proposed by Escher [

14].

Magritte, le saboteur tranquille, probably more than being, as Steinberg said, a “faithful militant” of surrealism, shows in his painting a clear and awkward glimpse of the reality that surrounds him, leaving no room for dreamlike appearance—rather sublimated in a detached attitude that has direct descents from the metaphysical atmospheres explored by De Chirico, his great inspirer—or for the unconscious drives expressed through the use of automatic writing (and painting).

Magritte often represents pictures in which a painting overlaps with the image of the real world, confusing with it and revealing itself as a representation only through the aid of small traces, such as the appearance of the edge of the chiseled canvas on the chassis (

Figure 17). Magritte in this way multiplies the game of reflections between reality and its representation: the painting in the picture that spreads the representation of the landscape is itself a representation. Situations of this kind, besides making the idea of representation more complex, contribute to questioning the solidity of reality. Similarly to what happens in Escher’s work, Magritte’s use of a sophisticated technique that supports the effect of likelihood contributes to determining the giddiness that may arise, for example from observing a solid and solid tree described in detail (

Voix du sang, 1961) in the trunk of which two doors open, one of which contains a sphere while the other one contains an entire building, showing a vacuum inside the trunk that crises, contradicting it, the idea of solidity that the image has aroused and subverting every dimensional value (

Figure 18). The paradox, in other words, is played in accentuating the credibility of the image and its contemporary absurdity, between its plausible and unbelievable being together. The picture describes an acceptable, coherent form that, in spite of the first impression, cannot be transposed into the world of phenomenal reality, of physicality. Something very similar to Steinberg’s synthetic designs that represent stylized human figures that, holding a pen in their hand, trace their contours in the air. Like the

Drawing Hands, these images directly represent an impossible situation, that the simplicity of graphic language—(although it may seem paradoxical) like the elaborate pictorial technique of Magritte or the amazing technical expertise in the lithography of Escher—aims to disguise.

Magritte has also developed in his works the game of ambiguity between the figure and the background. In 1928

Les Jours Gigantesques, for example, is the contour of the female figure that ‘cuts’ the boundaries of the male figure as well (

Figure 19). Both bodies, however, are placed on a gray field. In this way the two figures appear fused, without either of them clearly recognizable as background. Even more in the framework of 1965

Le blanc seign (

Figure 20), Magritte in representing a woman on horseback among the trees, fragmented the figure by superimposing to it not only the shape of nearby trees but sometimes the one of the furthest trunks and in one case also a free space which would have optically remained in the background. In this work, figures and background seem to alternate without any spatial logic and exploration of the picture traps the observer in a world characterized by the semblance of reality but physically inconsistent.

5. Conclusions

It could be easily pursued in the search for similarities between the work of Escher and Steinberg and the work of Magritte, and it could also be shown how the pleasure of astonishing the observer by representing impossible situations, still using a plausibility semblance, other than a solid tradition, the one that uses the topos of the ‘world on the contrary’, which dates back to ancient times, develops widely in the Middle Ages and lasts until the end of the nineteenth century. The taste for the paradox that was based on the overthrow of consolidated roles - for example rabbits that shoot at hunters, men who ride horse carriages - probably after the wide spread of Carroll’s novels since the twentieth century has left to a more subtle way of disturbing the observer or ripping off a smile, crippling the trustworthy relationship – “testimony”, if wanted - between reality and representation to insinuate a general suspicion of the solidity of everyday reality. Representation, in our common experience, is usually used to describe the reality with which it has a relationship, so to speak, of ‘conditioned specularity’. Likewise, it can describe an altered form, one part, can represent an obvious overturn, conceived to disturb us and make us suspect in our everyday reality. Representative forms of this kind - such as those experienced by Escher and Steinberg - mislead us: our confidence in the relationship between representation and our world is crushed. But it is so deeply rooted in us that even in the face of the absurdity of the image we have before, if it is realized in a just convincing way rather than rendering it as absurdity, we can easily imagine the existence of impossible worlds or end even to subtly doubt the solidity of our reality.

Douglas Hofstadter [

15] in the late 1970s described in an original way the conceptual affinities that link Escher’s work to the sense of the first Gödel’s incompleteness theorem, according to which it is possible to construct a syntactically correct proposition that cannot be neither demonstrated nor refuted within the same system. In the field of graphic representation, the internal coherence of an image, as Steinberg and Escher demonstrate—as well as Magritte—cannot in any way be a guarantee of its truthfulness or of the fact that it can establish a functional biunique relationship with identifiable aspects of reality. In spite of their mutual technical, formal and general mood, their graphic narrative, Escher and Steinberg show that they were both pervaded by the same anxieties and the same spirit that in the twentieth century, in addition to the truths derived from formal logic, crush the solidity of other representation systems. Even through the astonishment aroused by Escher’s work or Steinberg’s tasty humor, this awareness has crossed the cultural milieus of the last century.