1. Introduction

As an architect I believe fundamental a constant work on images. Today the images archive has become an essential instrument to work. However in an archive the images are statics, motionless, not producing new meanings, steady in their time. Working on images through the technique of montage means bringing them to life, capable of producing new and different meanings. This text want to define some operational rules through which images become an instrument to think about the architectural project. The project come to life and develop through a dialogue with our memory, the image are part of it. I choose the annotation form, collage on images taken from my archive, to determine a starting point in order to define the project form. Reference and practice are foundamental to build our vision of the world, Ettore Sottsass [

1] affirmed that in order to draw architecture other origins, information and catalogues are necessary to obtain ideas and models. That’s why every day, from my personal storage, I try to compose a catalogue of ideas to assemble from time to time, they are notes, possibilities which I called annotations by images.

Annotations are abstract forms, figure without background, used to assimilate the real. They create an imaginary useful for undoing freedom of image. The imagination creates semiotic links not matching the existent combinatory of image registered on a daily base.

In its Morphologie. City Metaphors [

2] Oswald Mathias Ungers propose a way of thinking and projecting through metaphors and analogy produced through images, showing the idea that throughout figures that later recompose from time to time on a project.

This school of thought and reflection go along with every architect work. To store images goes in parallel with creating images, which are slowly transformed on something else, or once compared define working models linked to specific themes.

The model is an intellectual structure setting targets for our creative activities, just like the design of model-buildings, model-cities, model-communities, and other model conditions supposedly are setting directions for subsequent actions [

3].

Images are the focal point of our culture, it’s very important to read again the words of the German architect. His thesis oppose the functionalism of the period when it was written. To O.M. Ungers theory is one of the many ways of seeing and knowing the world. Theory to interpret reality, to confer other meanings, to signs and consequently architecture as an instrument to translate theory.

Concretely O.M. Ungers try to simplify the project building process, for the same reason I believe is extremely important not to consider annotations as a project formal reference but only as circumstances to reflect on specific themes, instrument of thought.

Images so conceived become models not describing but underlining resolute conceptual decisions on a specific themes. Giving indications, creating the conditions to reflect, places to debate. The observer become content’s producer through his reflections. The structure, the form, the space, the necessity to use the architectonic shape as an expressive one, are secondary compared to the collected themes.

Montage is used as an instrument to take note on ideas, produce narrative strategy through simple operations: multiplying signs, scale exchange, reversals, grafts, superimposing, erasing. Necessary operations to pose relative questions on a project that can be applied on architecture.

The annotations are the first instrument through which we can put some order on a personal storage. The storage is generated by an affection on signs, a fragment, a space, an image striking us more than another, we store it, therefore to images we combine texts, quotes taken from books being its integral part.

Annotations put one next to the other make an interpretative Atlas of my reality. Taking notes is a project process and a practice I try to develop in a methodological key. It’s true that in this way I have the possibility to re-organize fragments of reality to build my Atlas.

To build an Atlas on a definition given by Aby Warburg [

4], who employ photos to build a cognitive process: cut out, reproductions are used to organize a tale, then the chart produced are fixed through a photo reproduction which determine an accurate place of the fragments, montages create sequence to be interpreted. To build an Atlas on that way is a research experience to construct new meanings. Notes to me can build a narration, retracing themes deal with projecting, during my architectural activity.

Today all this seems obvious, but I’m convinced that precisely because we are surrounded by many images it’s even more important to find a way of thinking through images, putting in place a cataloguing and organized process both physical and mental of this huge cultural asset, slowly replacing reality. Reestablishing a position inside a cognitive process first of all means to acknowledge on image a different quality. The serial has conveyed to this annotations a narrative shape much near to the drawing practice than maybe today can be once more used as an instrument to create a new language freeing the thought mechanism from the past trap of what we have already thought.

A precise order doesn’t exist, the same image refer to stories and different projects and can be employed in different way. In this process the observer becomes producer of contents. This kind of assembling operation refuse completely any formal value and attribute a different meaning from the original to the new images produced.

2. Materials and Methods

We live in an era in which looking has become the most widespread form of perception. The world seems to be filtered through images of all kinds. Reality almost vanishes, and we are shaped to its collective representation. Even the channels of memory are increasingly linked to repeated images rather than rcollections. Images are an obligatory point of contact between human beings and the real. Never before, as in recent decades, have seeing and looking so fully coincided with knowing.

To know the world, then, and to understand ourselves as we inhabit it on an everyday basis, first of all as observers. Action and its restitution in the visible field are irremediably the way through which we relate to each other.

The images with which we come into contact in every moment of the day are the direct visual project of what we hold inside ourselves, fragments of our memory, thoughts that very often influence our way of making architecture, more than actual experience.

There is no reality without image. There is no image without subject. And every subject is forced into this continuous confrontation.

The risk at this point is that these images may reduce our perceptive capacities. This is why we need to construct a method of comparison and thought connected with the images themselves.

There can be no result of a cognitive process that does not also and at the same time link back to the very process that generated it. Images are the product of different techniques. Those that interest me are manipulated images, used to produce new meanings, images that have undergone a transformation by means of montage. It is only after this type of appropriation that images take on subjective meaning, and only in this way is it possible to get beyond the objectual character of vision. Only in this way can perception cease to be exclusively a process of an archival order, without any interpretation. Montages can be of different types. They act on the image as object or on a set of images selected and positioned according to an order established by the viewer. Therefore they construct a sequence that is repeated inside my archive. The archive is organized in the form of a blog [

5] or on social networks.

Montage, then, as an ordering principle of the reality that surrounds us. Photography is an image without a code. Though it is clear that certain codes influence its interpretation, they do not consider the photograph to be a copy of the real, but rather an emanation of the real past: a kind of magic, not an art. Asking whether photography is analogical or encoded is not a way to find a good criterion for analysis. What is important is that the photograph should have documentary force, and that the documentary character of photography not be based on the object, but on the time. From a phenomenological viewpoint, in photography the power of authentication surpasses the power of representation.

The realists, of whom I am one and of whom I was already one when I asserted that the photograph was an image without a code—even if, obviously, certain codes do inflect our reading of it—the realists do not take the photograph for a “copy” of reality, but for an emanation of past reality: a magic, not an art. To ask whether a photograph is analogical or coded is not a good means of analysis. The important thing is that the photograph possesses an evidential force, and that its testimony bears not on the object but on time. From a phenomenological viewpoint, in the photograph, the power of authentication exceeds the power of representation.

Montages

An example of montage to which I often refer is the one theorized first by Aby Warburg [

6] and then by Georges Didi-Huberman [

7], who both transformed the use of images into a tool of research.

Through these two figures I have constructed my analytical and interpretative path through not only the world of art.

Didi-Huberman seems to be primarily interested in the interpretation and use of images, rather than their ontological status as pure, simple forms of the real. Who looks and how are more important than the object to be observed, in short. This type of montage is done by seeking the material singularity of the visual document, inserting it in the same time inside a play of relations capable of producing a true cognitive shock. The archive (the image as pure object, a datum linked to its iconic meaning) and the montage (the placement of that datum inside a dialectical system) are the two essential poles for looking at the contemporary world.

A discursive practice focused on the presence of the gap, the interruption, on continuous découpage and rémontage, an accumulation of “symptoms” more than of “data,” of unexpected motifs, utterly transversal relations reconfigured each time inside a procedure without ever having a solution of closure, the montage seems to be the only critical-visual device to obtain a type of non-standard truth. Working on discontinuities, on the structural breakdown of that image-concept short circuit any visual practice always runs the risk of carrying with it (behind every image the danger always lurks of the automatic comment, the stereotype, the immediate and prepackaged term), montage becomes a true form of plunder and renewed raiment of the gaze.

If the image as such, as we read in Devant le temps [

8] in 2000, is not the imitation of things, but the interval made visible, the fracture line between things, then the gaze too is interval, line of fracture. If the images does not spring from an orderly continuum of causes and effects, but is a dialectical vision composed of past and present in eternal collision, a sudden shock in which to be able to grasp the lacerating discontinuity of time, then the gaze too, the critical gaze, seems to make shock, “collision,” dialectical friction the elements of its vision, the load-bearing members of its very structure.

There is no single reading, as there is no single possible sequence of images. Every eye can be critical in the face of history literally opening up to a non-standard dimension of vision (and discourse).

3. Discussion

In my work montage takes on great importance because it is the operative tool, the medium, through which to interpret the personal archive, constructing the annotations that form an interpretative Atlas of the real.

I see montage as a principle of order, rather than a technique of assembly.

Montage is a principle capable of putting heterogeneous orders of reality into relation with one another, a principle that produces knowledge, precisely as theorized by Aby Warburg with the construction of his Mnemosyne Atlas Montage can be used to establish relationships among a series of fragments belonging to our memory or extracted from reality to be combined and to define images to use as a model for interpretation.

Interpreting a model is what Walter Benjamin [

9], in his essay On the Mimetic Faculty, defines as reading what has never been written, before all languages, in the entrails, the stars or dances.

Thus considered, montage is a device capable of organizing images, combining them. Perhaps it would be clearer to define this logic as an operation of deconstruction of some of the images that define the reality that surrounds us in different temporal zones, a disassembly that conceals inside it the necessity of a reassembly of different times. Also the time (of the image), in fact, takes on a fundamental role in this way of operating. The time of an image has a dual meaning: that of the moment in which it is selected, and that of the moment in which it becomes part of the archive (the exact moment in which it becomes memory) to be projected towards another time, that of the moment in which these annotations take form.

The contrast between temporalities creates a new one that does not belong to the present, but neither to the past. In his Images in Spite of All Didi-Huberman [

10] emphasizes that the knowledge that happens through montage implies that the value of this knowledge cannot be guaranteed by a single image. The images (or fragments of them) thus selected have meaning only if they are juxtaposed with other images.

The comparison and overlapping of images by means of the montage create other images, the annotations, that become part of a personal atlas and reappear in the precise moment in which a new use for them seems to be evident.

Montage grants us the possibility of rejecting the rigidly pre-set form—freedom from routine, giving us the dynamic faculty of assuming any form. Speaking of montage, one cannot help but make reference to S.M. Ejsenstein [

11]. For the Russian director, montage is not a thought composed of pieces in succession, but a thought that arises from the clash of pieces independent of each other, as in Japanese writing where the meaning springs from the juxtaposition of ideograms combined to produce the meaning.

Two overlaid images, even when of different origin, produce an illusion, a disorientation. Everything comes from the non-correspondence between the first image imprinted on paper and in the memory of those who recognize it, and the second image, initially conceived as a foreign body: the conflict between the two generates sensations, disorientation, curiosity, but also clearly defines concepts on which to then construct projects, in a second phase or phases.

Eisenstein reaches the point of specifying precisely this: the montage emerges from conflict and collision. The montage is always conflict, conflict between fragments, a style of writing and a method of investigation aimed at clarifying, in his case, the identity of cinema and its position in the universal history of art forms. As in Warburg, Didi-Huberman and Benjamin, it is the encounter with the temporality of the image and of the instruments that convey it that forces history to develop new ways of reconstructing and displaying its formative processes. Montage seen not as a form of artistic composition but as a tool of research to orient ourselves in the chaos of the history of forms.

Premises also found in what Eisenstein himself calls intellectual montage, a montage capable of becoming a form of thought and knowledge, manifested not so much in a linear arrangement of images oriented towards the creation of a narrative continuity, as in the exploration of the productive force of conflict, of the collision between heterogeneous pieces: montage is not a thought composed of pieces that follow each other in order, but a thought that originates in the collision between two independent pieces.

3.1. Rules for the Construction of an Image

Montage is the ordering principle that helps me to construct annotations.

These annotations have to be hospitable, they have to encourage viewing and establish a relationship with the observer. It is important to establish a visual dialogue between the space one wants to represent, the idea that attempts to give it form and the context one tries to construct as the background. An ability to recreate a measurable space, a precise geometric structure, must be demonstrated. Which does not form but structures the space.

3.1.1. Places

Once the space and the meaning to be attributed to the image have been suggested, it is necessary to underline the evocative power of the fragment that has been used in such a way as to grant architecture the power to create a precise identity for the place, identified through the iconic meaning of the building, what I call the construction of an imaginary place.

Otherwise, it could be a hybrid place created through grafts of pieces of real buildings, or parts of buildings that have simply been imagined.

That’s why is important to choose the image to begin using them as an introduction to the transformation. What I see in this image is a project which does not exist yet or better take the shape from the existent transformation.

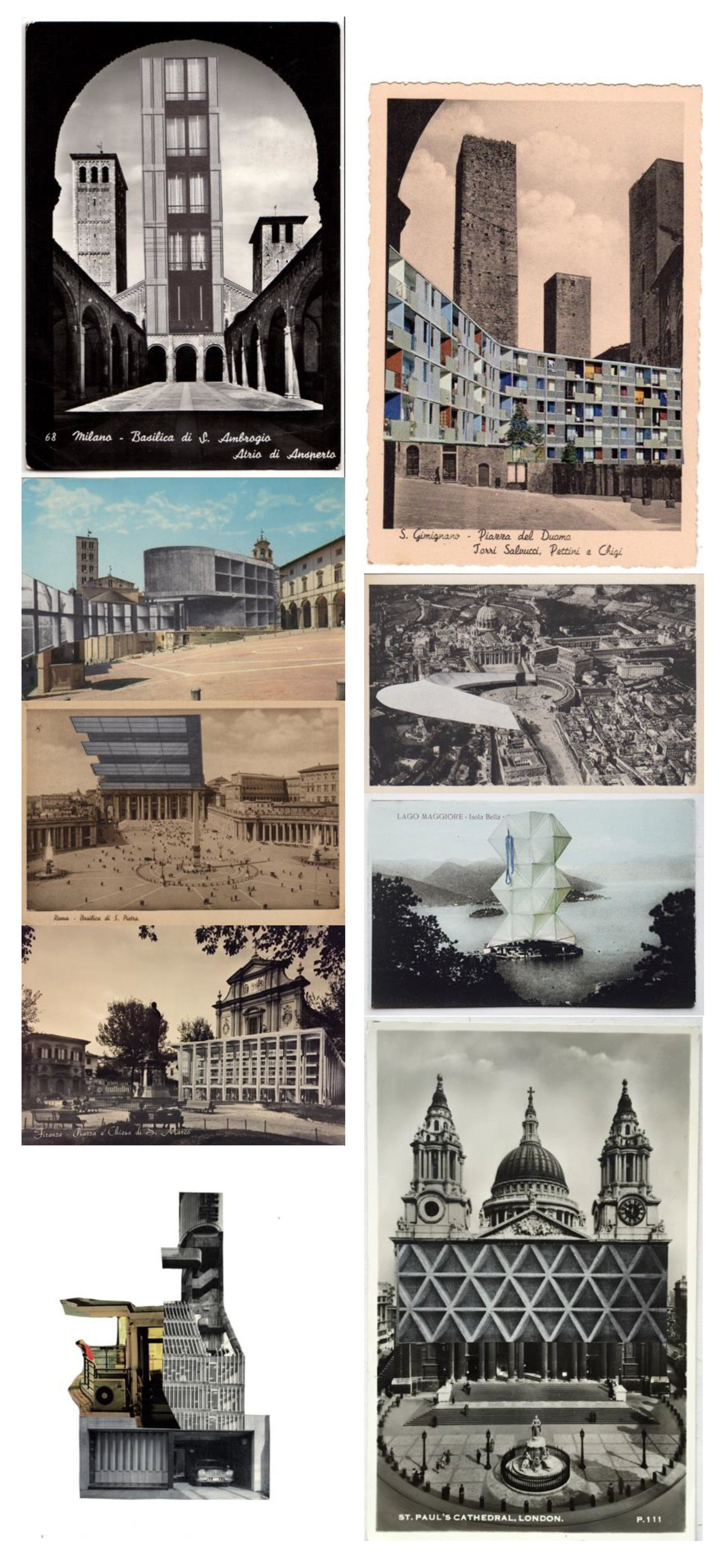

Then once the image chosen, it could be a photo (representing an urban site), an architectural sediment in my memory, a post card, (

Figure 1) I proceed with the re-elaboration as a shape of the image explanation.

The images chosen are other area of imagination which contain real places, amplifying some, refusing others. They are not only part of my memory but also part of the collective one.

After I choose the image I search for single fragments cut and stored during sometime recording my daily activity on projects, material shapes, objects. Images and fragments start to get in contact within them through accurate choices. One of this is the anachronism.

The anachronism it’s a chronological mistake because is situated in an historical period where event and phenomena happened in another era. This intrusion of an era into another offer the possibility to reduce the distance between objects and different spaces, fragments and codified images take on a new meaning, the images loose their status of monumental body and of documental sources (it’s not by mistake that I have chosen postcards).

A way to imagine together time and images not as different interpretative palimpsest but as a combined one, the image become the center point to reflect about time.

It’s natural to ask oneself what time we look at when we are in front of an image?

A plural time, a collage out of sync temporality as Didi Huberman assert when he says that image has often more memory and future of the one looking at it.

3.1.2. Times

How to evoke time or, more precisely, how to play with past time by bringing it into the present. The image can create, structure and confuse times.

An image is normally a single frame. There are nevertheless many works that show different narrative episodes simultaneously.

Image is a relationship with the past, an attempt to read again the common memory creating a new constellations of sense. The collective memory filtered through the individual one can offer a fabric of dialectical images, shaping a relation with the past based on the principle of quotes. In this way it can be extrapolate from a context and something can be reused. Quoting is a passive way of taking something but, in the same time, an active way to deduce from its context an element giving to it a new life.

The image is a form of unattended and flashing contraction, it has an effect of intensification and in this way establish the fundamental process through which we can refer to the past.

What Benjamin propose in this sense, is a way to turn to the past through images able to trigger a mechanism of thought useful to the project. The past reactivate through a dialectical image and in the same time its destroyed and transformed. Destroyed mean taking away from the past its irreversible condition, of something inexorably accomplished, necessary, continous. Destroying the past as it was: then the past become in the present a possibility for our future.

The images so produced are not an arrival point, are moreover a starting point containing the project guidelines to be developed through the planning instruments.Now it has to appear clearly a fundamental point concerning the link between memory and image, the last can be stereotyped, recurring, always the same and can on the opposite be creative, producing a new sense coming. Quoting its only apparently a passive way of taking something back, but in the same time, an active way to pull out an element from its context, giving to it a new life in an unpublished constellation of sense.

3.1.3. Spaces

So it is not so much the image that results from montage that interests me, as the space between the images, which I consider the true space for mental utilization.

This space is the place in which the certainty of what I see runs up against the doubt about what I seem to see or to have glimpsed, if only for an instant. It is from this space that the images should be observed, to manage to assign them a meaning. This device activates spaces of comprehension, creates a physical and mental place, simultaneously visible and invisible.

In my way of operating I try to carry out simple operations, derived from the practice of collage, updated in a dialogue between analog and digital.

Many montages, in fact, are done by hand and then digitally reproduced. In the moment in which they are reproduced a catalogue is also defined of pieces, to use again and again in time.

But the most important moment is the one that attempts to assign a three-dimensional character to the digital image through printing on overlaid panes of glass.

Thanks to the overlay of the panes, the fragments regain their singularity and determine the necessary passage from loss of meaning to acquisition of new meaning.

In my way of working, I am attracted by certain operations that characterize the form of the collage, but at the same time can be a mode of construction of the architectural project.

The digital images come from the overlaying of planes. The printing on glass maintains this layering and the image loses its iconic value, becoming a device capable of producing variations. Thus the image is never finished and always awaiting something; the meaning changes depending on the side from which it is observed. The machine (the device) does not produce the image but coincides with it, becoming a sort of screen capable of creating a visual system to continuously interpret. The eye of the subject perceives one layer instead of another, making the viewing dynamic.

This device is a fragile system that is not able to rearrange itself in a single thing, because the unity no longer exists, the forms of representation no longer have a single meaning. The layers play on a dialectical level and the meanings emerge in the space that exists between the planes.

In short, for an instant that could last a lifetime, you are faced with an invented, “defigured” image, whose force lies in what it comes from… a latent energy, of lines and expanses, touches and points, something like a pattern removed from the action in progress, but which is then its power.

Raymond Bellour in his L’Entre-Images [

8] aptly explains this path that is not based on the construction of the image but on the reading of the meanings hidden between images, when he says that through the invention of a new image, that in part releases itself in its photographic transparency to make room for other materials, a new physicalness is introduced. The work on disassembly and montage is precisely this—to manage to create a physicalness of the object-image that, through its defiguration, opens a prefiguration.

The between images is space that is still new enough to be considered an enigma, but already structured enough to be able to be circumscribed… a reality of the world that no matter how virtual and abstract it may be, is a reality of image as a possible world.

Montage is always conflict, and as such it is a realization in images of dialectic, a dialectic that is always open and never destined to be definitively resolved in a synthesis.

4. Conclusions

The term “form” has taken part of the architectural discourse in such a pervasive way that nowadays we can’t really talk about architecture without having to bump into it. Along with the development of the philosophical thought, the word Form has inherited different meanings. In my opinion, the form has to be found in the action of looking at something and not in the thing itself. Moreover, it is as powerful as our mind is capable of recognizing the possibility of reinvention of the images around us.

Both as Professor and Architect, I consider important to teach how to look and how to build the form of objects and spaces that surround us. It is necessary to learn how to select fragments through which we can digest our own ideas to finally give shape to the space. Form is nothing more than a device of our though and, as such, it can’t have a specific exhistence prior to the thought itself.

The thought arises and developes around a single image; this image transforms inheriting certain meanings and assumes infinite combinations. All through the transformation, the form adjusts continuously untill reaching a moment where the idea takes over all the rest.

I am interested in the exact moment when such accumulation becomes formless. That formless very dear to Bataille, who carries on producing material with a rythmic operation in which forms vanish and stand out again, now exhuberant, excessive. It proliferates, hence generating, through explosion, torn apart, open forms.

The formless, as a matter of fact, is the collision of forms, their contingent and non substantial condition: when we use this term we intend it as an adjective and not as a substantive. It is a structure of undetermined form, capable of infinite combinations. Therefore, an image procuces infinite images that beome conceptual models upon which we base our projects.

At this point, I find relevant to introduce the dialogue established between images, the origin and the manipulated image, outcome of a vortex, in the significance of dialettic image that Benjamin attributes to it. Such vortex image is not the imitation of things but rather a fracture cut between them.