2. Changes in Pages: Historical and Critical Notes

The systematic study of wordless books is a relatively recent field [

8] and the theoretical references of the subject investigated, dealing with children’s literature, necessarily belong to a range of disciplines—pedagogy, narratology, iconography, philosophy, literary criticism and art critic. According to the method used by the Bologna school, which refers to the teachings of Antonio Faeti, pictures in children’s books must always be considered in relation to the whole visual and artistic culture, with their apparatus of metaphors, references, filiations and respective grammars. A student of the philosopher Luciano Anceschi, who devoted many reflection about the poetical views of authors in literature as their ways to depict the worlds, Faeti since his pioneering essay

Guardare le figure [

9] has always addressed to the production of children’s images and illustrations the attention of those who think that

looking at pictures it is in the experience where the ability to see is built; in illustration picture’s makers offer hospitality for children meaning in this way that they are part of an active cultural community which aims to exercise critical

ways of seeing and that children belong and are part of the collective imagination from very early childhood on. In this sense, asking which children’s poetics and poetics of the world are chosen by the authors of children’s visual and literary works means asking about the ways in wich construction of our view of the world grow up from childhood on.

In children’s publishing, there is an implicit—and at times explicit—editorial position, which refers to one or more ideal recipients who are willing to “sit together” and look and read together. This is the typical dual audience of the picture book, as stated by Sandra Beckett in her essay

Crossover Picturebooks in which, in 2012, the researcher dedicated also a whole chapter to wordless books, reconstructing some historically relevant moments and reviewing some classics [

10].

In Italy, thanks to pioneers such as Bruno Munari and Iela and Enzo Mari, wordless books for children were designed first and foremost by distinguished visual designers interested in children’s visual perception and the experimentation of book shapes. Among the pioneering examples of excellence in this book genre, we could mention in fact the illegible books by Bruno Munari [

11] (

Figure 1) and picture books which narrate natural cycles with few colours and rigorous forms such as

La mela e la farfalla (

Figure 2) by Iela and Enzo Mari [

12] still reprinted today.

The international historical perspective, i.e., that of Sandra Beckett or the Korean scholar Jiwone Lee [

13], refers to these Italian experiences as concerning the roots of the modern art of wordless books.

Broadening our view, we may suggest many possible genealogies for placing the visual narrations of books on a timeline. In this sense, the contemporary wordless children’s book is simply one of the lively and continually changing heirs of the many “silent” narrations by images which have always characterised man’s expression through figures, starting from the cave paintings in Lascaux to Trajan’s Column and the pictorial cycles of Giotto and Paolo Uccello (Ducal Palace, Urbino), to the

Biblia Pauperum ([

8], p. 79) which talked to both illiterate and literate readers through contaminations with other languages as pantomime, the history of chronophotography, photography, cinematography, silent movies and even music, crossing the evolution of the book from

codex to

volumen and finally to printed books, and the evolution of the silent novel of the Thirties and cartoons like Lynd Ward’s

Novel in woodcuts. In the constant dialogue with visual design, children illustrations have always belonged to a coherent, cohesive universe, since their own grammars and the possibility of telling stories made of signs and shapes are as understandable and disorienting as the world itself.

The genealogies of the silent book therefore continuously refer to the book form and the child recipient and place different dictions and visions related to poetical themes and concepts such as silence, complicity, metamorphosis, wonder, silence and movement.

Among these, works which are very different in shape, recipients and contents have a special place: above all the ancestor book can be considered 1677’s

Mutus Liber ([

8] p. 84), a silent alchemic manual on the Great Game whose pictures contains the instructions for the steps needed for transformation, legible and understandable only by the initiated. Addressing only the community with the interpretative skills required to read the pictures and organise them in such a way as to identify the precious indications for performing the steps in the Great Game. Worldess books are always addressing to a community that share common visual alphabets and collaborate to build this international and collective sharing of images and imagination.

In this regard, here is a terminological note: the expression

silent book has been used only in the last decade and in Italy for the first time; then it spread to the international community and today used alongside the more pragmatic one

wordless book. This has been possible also thanks to a more embellished and rhetoric linguistic vocation of Italians during the Silent Book Project for Lampedusa ([

8] p. 43) promoted by the Italian branch of IBBY (International Board on Books for Young People), the major international non-profit organisation which promotes reading, and other international occasions. The allusion to silence can indeed be found in very many critical works dedicated to this type of picture book. The perceptive possibilities of seeing demand a type of concentration strictly linked to the exercise of the art of silence and observation, as in monasteries’ traditions and meditation. Silence is not only a pedagogical possibility offered by this kind of narration, which breaks the chain of too many words of scholastic habits and reviews the educational hierarchies by facing with a text which does not necessarily need to be said by a literate reader in words in a loud voice but rather seen and read with the eyes and retold in new words for every reader. In pedagogical terms, it turns the traditional roles of reading upside down: the adult is no longer the first reader, the initiated side that knows the written sign and acts as a go-between, at times with a rather hurried approach, dulled by normative obsession or cognitive control, and loses the plot, while children are the dynamic readers of pictures, as John Amos Comenius underlined in the mid-17th century [

13]. Silence is also one of the favourite poetic themes of silent narrations in itself, underlining an aesthetic intention and a clear aesthetic education. Silence in wordless books also means listening to other languages, those of signs, colors, visual sequences and shapes also, in a time that slows down and in that space of solitude where multiple narrations are possible.

In contemporary wordless books therefore meetings of new levels of narrative take place beyond words, through natural and fantastic metamorphosis and dreamlike spaces where imaginative and interior meanings are built and so invite to be discussed and considered.

Wordless books often tell stories about the very capacity of pictures to offer narrations crossing space and time, rich in that we call “visual culture”.

Flotsam (

Figure 3) by american three times Caldecott award winning David Wiesner [

14], one of the masterpieces of this genre, is an authentic programmatic and metatextual manifesto.

The underwater camera found by the lead character, a boy, is a device which declares not only the extraordinary power of cultural images and their circulation in space and time, but also confirms children’s belonging to the visual universe of the collective imagination, that reservoir of interior and archetypical, cultural, natural, artistic and dreamlike visions in which our lives are immersed and from which our dreams, hopes and future narrations take shape. It is interesting to note how this is inline with the 1989 UN Convention on the Rights of the Child in articles 13 and 31 (The Convention on the Rights of the Child, approved by the UN on 20 November 1989, can be downloaded from the website of the Italian Ombudsman for Children and Adolescence:

www.garanteinfanzia.org.) an aesthetic right to “seek, receive and impart information and ideas of all kinds, regardless of frontiers, either orally, in writing or in print, in the form of art, or through any other media of the child’s choice” and to have access to the greatest variety of high-quality artistic and cultural production.

Alongside the exercise of poetics and the aesthetic encounter are wonder and marvel: the sea in

Flotsam is full of giant squids, lost objects and mermaids; an infinite sea like that of stories, literature and art, alternately suggesting familiarity and disorientation, moving towards knowledge and change; a sea of images evoking and containing worlds; a silent sea that animates, reawakens and narrates through pure vision without words. Also wonder leaves us wordless, as we read in the following passage by Silvano Petrosino ([

15] p. 107):

Wonder does not wait for the spoken word, the explicit formulation (sound, graphics, or other forms) of the words, to be a word… The silence which always accompanies wonder…is not at all the expression of mutism, but rather the place of clamour, the condition of a continuous being questioned and answering, of being called on to answer… The time of wonder is not the momentary silence of glitter, the idolatrous suspension before what terrifies me, but it is a time of words in which this glitter animates-me-and-I-animate-it as a question.

Disorientation, wonder and marvel are aesthetical and existential conditions frequented by the silence of wordless books right from the very beginning. They are linked to the quality of humorism in one of the first books of this type, the work of the extraordinary Swiss-born French illustrator, Théophile Alexandre Steinlen who, in a short libretto of only pictures entitled

The sad story of Bazouge [

16] (

Figure 4): places on the page a crow drinking from the glasses left on a sumptuously laid table after a meal. Page after page, the crow drinks and changes expressions: it is only his increasingly hallucinated stare and an uncertain posture in Steinlen’s drawings that tell us what is changing in its mood. The crow drinks more and more, at the end of the libretto it is totally drunk and falls to the ground. The trick lies in turning the pages and following the author’s visual capacity of observation, imagination and illustration, picturing the eye of the crow slowing down, moving away, moving back in, focusing—just like in the cinematic strategies—on what he is intent on, inviting the reader to look at the same thing. The silence of this sequence creates a very strong complicity between the author and the reader, and an humoristic irresistible effect, because the author of a wordless book looks confidently towards the reader’s ability to read images, he does not take them by hand but shows only what he wants them to look at and to fill with meanings and emotions.

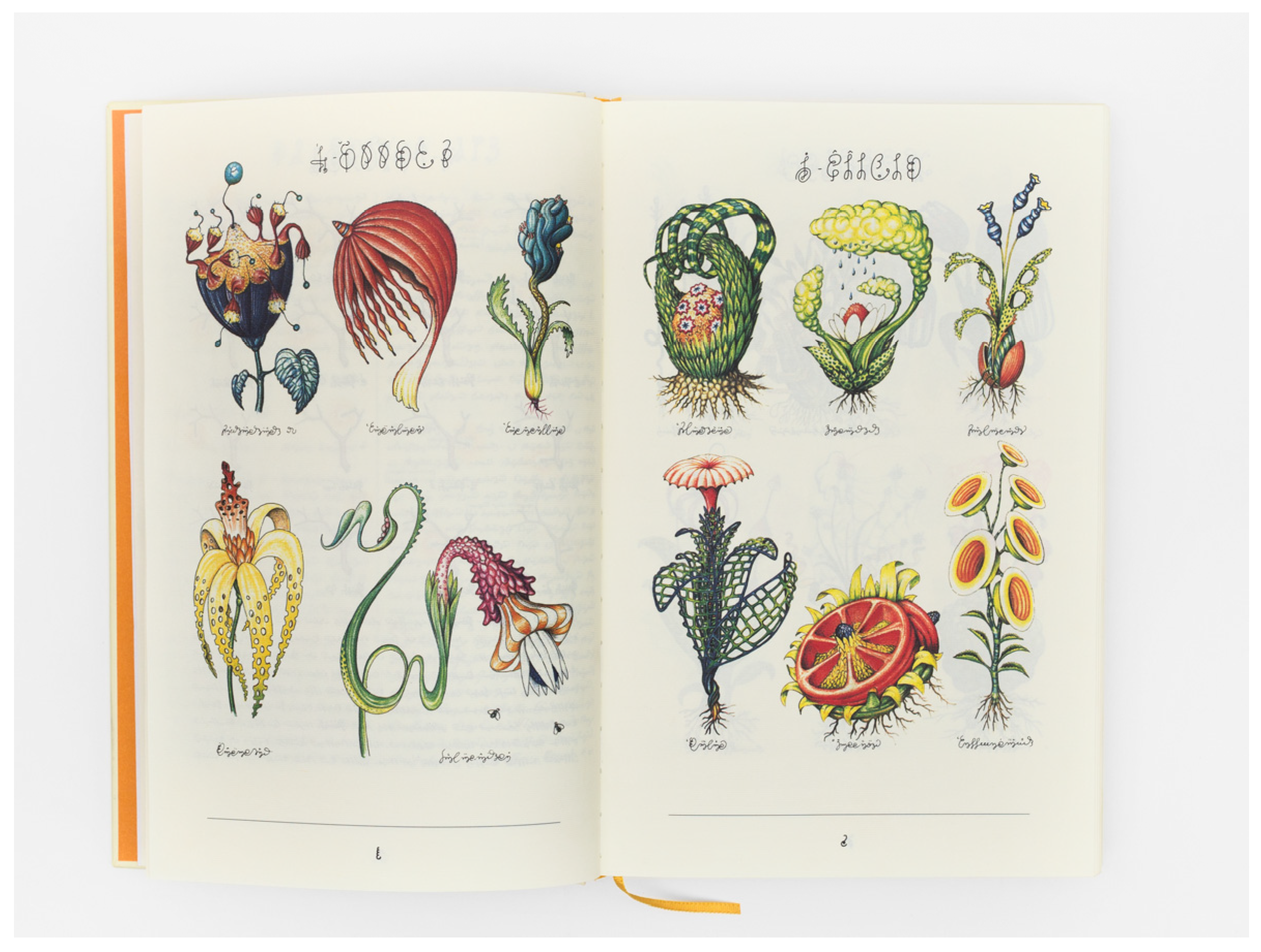

Another mandatory historical reference, yet so eccentric and unclassifiable as to be a book not designed explicitly for children and printed by Italian publisher, designer and art collector, Franco Maria Ricci:

Codex Seraphinianus [

17] (

Figure 5) first published in 1981, is a visionary and mysterious work created by the Italian designer Luigi Serafini, characterised by astonishing metamorphic figures in an imaginary world and an asemic text impossible to decipher.

Like forgotten ancestors, who continuously return to show themselves in the physiognomies and memories of their heirs, also artists as Edward Muybridge [

18] and other precursors of the cinema, using chronophotography pursuing the aim of creating the moving world in pictures, impressed their recognizable signs and poetics in the grammars of the wordless book. The visual complex research into how to render time and movement, shared by different visual languages and form of art, combined with the poetics of the missing and empty spaces as a form of voluntary reticence being retold by visual sequences are elements that find the ideal space for expression in wordless picture books.

Thus the silent books on the contemporary international bookshelf tell of a girl playing with a wave (

L’onda, by S. Lee [

19]), the transformations of the world in a dream (

Free Fall, by D. Wiesner [

20]), journeys chasing signs and colours (

Journey, by A. Baker [

21]), migration challenging habitual signs and geographies

The Arrival, by S. Tan [

2]). They tell of unknown alphabets, knowledge of the metamorphosis of nature, the possibility to suspend verbal language to recover perception through other senses, the need to communicate beyond the boundaries of the word, diversity, the belonging of the mandala and the page symbolically to the cosmic universe, the belonging of those who are different, who have just arrived, whether migrant or child, to the collective imagination, and the right of this belonging and the occupancy of the world of signs and shapes.

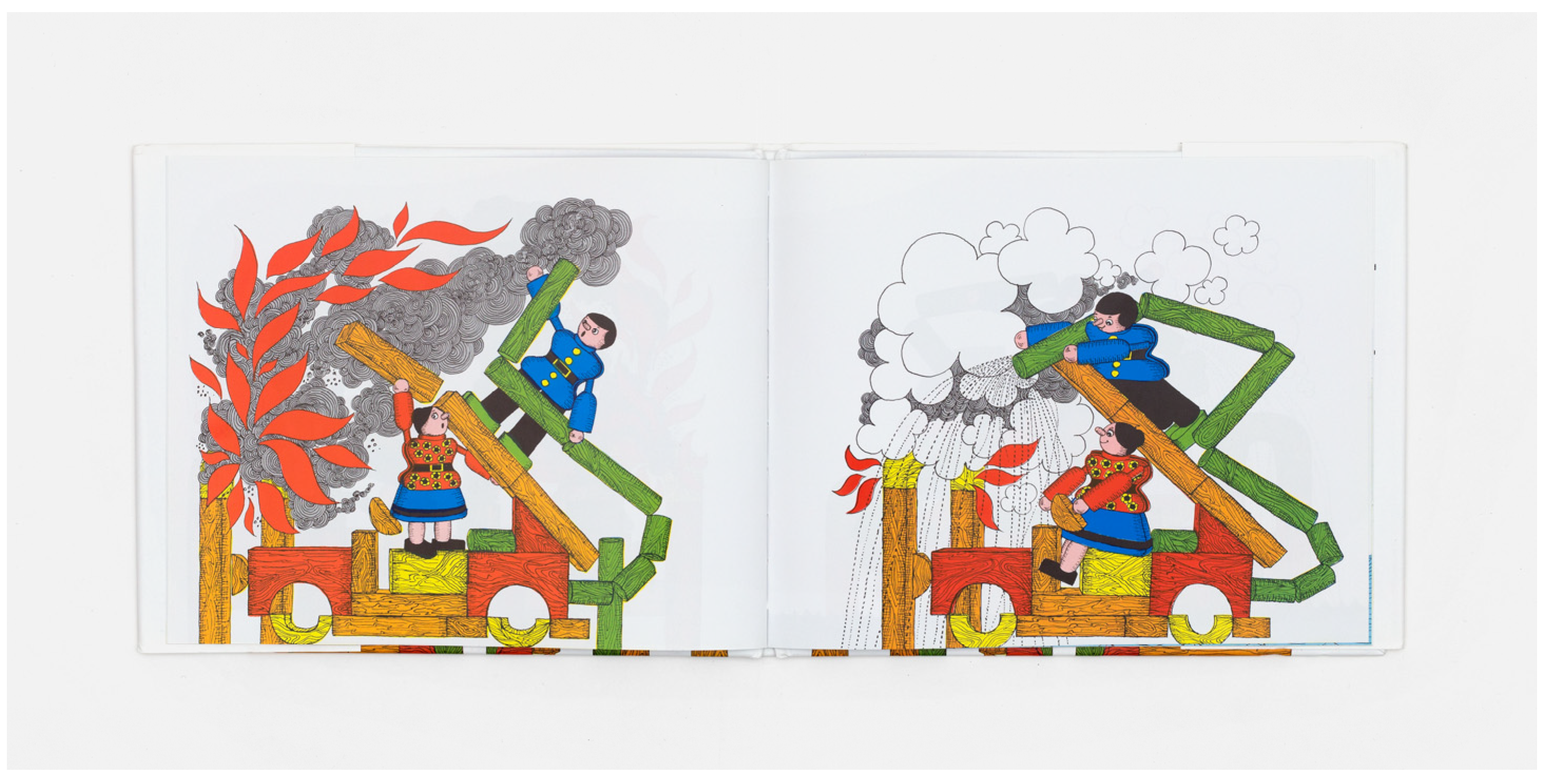

They tell of the world in continuous movement and metamorphosis, in Iela Mari’s books and in the Pat Hutchin’s picture book

Changes,

Changes (

Figure 6) [

22], published at the same time as David Bowie’s song of the same name, and in the dreamlike, surreal transformations we find in all David Wiesner’s worldess picture books.

A more specifically narratological and pedagogical review of the silent book’s poetics, in other words a review of the visions of the world that authors give in their narrations by images, reveals surprising repetitions. Metamorphosis, a great and universal literary theme, is often at the centre of a narration which thrives on sequences of pictures and relationships between forms and which regards childhood, that season of change

par excellence, even though man is always evolving and is never really

adultus [

23] (etymologically, completed).

Lacking, as a clues structured text or a poetical reticence or the space between moments and transformations phases, as the interest in what is invisibile, as indeed in all written literature, as demonstrated in Nicola Gardini’s critical essay

Lacuna [

24] is also illustrated literature in pictures and visual narrative. The reader ventures through the pages and has to fill the signs with meaning, just as he fills the spaces between the words. Educators clearly fear this having to trust the author and his visual language, it is an exercise of faith which is not unrewarded, in the case of masterpieces of this genre. The thread of sense, or nonsense, leads the reader to turn back the pages to check theories, to jump in surprise at sudden revealing of meanings, or even laugh, or change his mind, when the page confirms or even upturns a previously interpreted theory. Thus the silent book teaches that literature is a place of shortcomings, a place of completions and suspensions, meetings with the imaginations of others, a possibility for the knowledge of man and his constitutional incompleteness. Thus the silent book invites adults, educators and readers to exercise lateral thinking and abandon normative certainty, reassessing the value of open questions and “big” thoughts [

25] to the detriment of the need to continuously evaluate and measure the utilitarian acquisition of skills.

There are many surprises in the educational field when we experience reading wordless books: at the end of the Italian research

Visual Journey (already quoted above) in the international project focusing on the reading Tan’s

The Arrival [

2] (

Figure 7) with immigrant children, more than one of the children involved, in a semi-structured interview, said that he had “learned Italian”, even though this was not one of the objectives we set as researchers. During other interviews with the teachers, it was noticed that this was only one of the clearest facts reported after the experience, which lasted for a few weeks, of the collective reading as the other issues were decisive, including a greater motivation of children towards discovery not only of other books but also of dialogue with the class group, and peers, as well as a much greater self-esteem and trust in self-expression.

The story of a man who migrates to an unknown country, told only through pictures, in a programmatically disorienting symbolic and iconographic complexity had, together with the collective reading method, dilated the space of the book through open questions and mutual listening. In that silence, in the complicity of reading, visions, exchanges, stories and readings were produced and built a community of readers, through the exercise of the negotiation of meaning and co-construction, active citizenship was also exercised. The relationship among the readers and the urgency of sharing their own aesthetic experience were the drive for linguistic expression that was stronger than any form of teaching. The poetics of disorientation, of the metamorphosis and of the lacking are close to the sensitivity of children who continuously wonder about signs, clues or changing forms. Children, like artists, travellers and migrants, continuously experience disorientation, metamorphosis and suspension. They look at the very small, the detail, the minuscule, the insect, even the invisible with the same urgency as the very large, the immeasurable extent of the stars or time.

In the same way, silent books are part of this broad spectrum of poetic measures, sharing with Western and Eastern philosophy the interest for the very small and the very great. According with this perspective the picturebook is itself a

mandala, i.e., a coherent community of signs and shapes, continuously referring to the world beyond its frame. The theme includes not only art and spirituality but also science, as can be read in the magnificent book by US biologist David George Haskell, who observed and described the same portion of old-growth forest telling of the thousands of ecological relations taking place in the environment [

26]. Image is mediator and mirror, window and summary of the world. The very small is also childhood itself, the everyday moment, the hidden detail to be found in every page. The very great is the circularity of natural metamorphosis, the continuum of every story that can be repeated infinitely, like the very story of the circulation of pictures and stories. The silent book confirms children’s right to be informed and involved in this broadness of thought, vision and ecology of the mind [

27], which is cultural, spiritual and aesthetic. Finally, the silent book invites us to see.

Wordless books or silent books are books which are usually composed of sequences that do not have the fast rhythm of the cartoon, but which offer a rarefied visual story, where the scene changes with every turn of the page, bringing metamorphosis and movements which are understandable even in early childhood and which constitute the very first possible discovery of the book-device. They are visual devices and artefacts that are far from simple, they attract and absorb visual designers who experiment the visual perception of children, the synthesis of shapes, the challenge of the synthetic narration of universal topics.

Therefore wordless books require the learning of alphabets to be understood, they require the knowledge of visual grammars, the habit of exercising the eye and the meeting with art, and do not possess—we refer to narrative silent books—millions of possible interpretations but rather precise paths of meaning set forth by the author, often on several levels, which the reader must follow, using—often openly declared—clues, in the several readings required of this type of book, a synthetic and yet complex form of poetics, just like poetry.

The metatextual discourse between image and imagination is also expressed in the large quantity of references and citations picturebook authors disseminate in their works: internal references and references to traditional paintings, cinema, the history of photography.

The silent book is thus in a borderland, it makes the geography of the visible understandable and accessible to the very young providing a discourse that is readable in itself, beyond the very boundaries of languages, history, signs and forms. The border, the solitude, the silence and the experience of the limit and the crossing of it in the identity making process, as the meaning of empty space, the white color and lacking are other recurrent poetic themes represented in contemporary wordless books. The corean internationally acclaimed wordless picture book’s author Suzy Lee devoted an essay to her art and called the illustrated volume

The Border Trilogy (

Figure 8) [

28] where she proposes critic commenting about her wordless books Trilogy that includes

L’onda (

Figure 9 [

19]),

Ombra [

29] and

Mirror [

30].

Figure. 8 Lee S. (2012), La trilogia del limite, Corraini, Mantua.

Lee writes about the white space of the page being an expressive choice and the limite between the two spreads a narrative element, capable of representing in images the relationship with the unknown, the unseen, the impredictable, so the possibility of experiencing wonder and surprise of discovery.