1. Introduction

In Palermo, in May of 1946, in an urban context strongly altered by the bombings of the last global conflict, the Fiera del Mediterraneo, a small district on the northern outskirts of the city, was created with the great ambition of becoming a central hub for exchanges between Sicily and the countries of the Mediterranean.

This idea arose from the legacy of the great 19th-century expositions, although the Fiera del Mediterraneo was presented as a modern fair, determined to tackle and develop the complex theme of the commercialization of artisanal products and of the new economy industries addressing the Mediterranean area.

Sicily has always been the ideal bridge between Europe and the shores of the Mediterranean. The desire to assume a privileged position in the network of commercial trade is evidenced by other fairs of the past and, above all, by the splendid Palermo National Exhibition of 1891.

While analyzing the theme of the relationship between modern architecture and the places of commercial production, there emerges in this context the elusive theme of the role of the graphics and the decoration of stands and exhibitions for the purposes of visual communication.

A basic historical link is outlined showing the value of the modern urban scene that knowingly uses all the tools of visual communication in order to function as a visual machine comprising architecture and scenography.

2. The Places of Commercial Production in Contemporary Times

The

Fiera Campionaria trade fair, in the post-war period, is the place where the setup takes shape according to a mechanism aimed at the commercialization of industrial products. An evident and obscure place that allows ample reflections on the idea of architecture, of the city within the city, of the urban landscape, through the mediated channel of representation. The setup must be able to assemble, and often quickly disassemble, a form of visual representation; in this case, to make the object to be exhibited more perceptible, visible, evident (

Figure 1).

The fair becomes the modern market for products, a place for promoting merchandise, undifferentiated stands, and contamination of typologies sharing the need to be known by a guided public, according to a targeted promotional marketing action. With the industrial revolution, a new idea of production is realized, new buildings and specific places are created which, as well as welcoming new products, are also capable of revealing the industry’s innovative aspects. From Paxton to Eiffel (to name only the best known), the protagonists of the last century have given life to the modern concept of exhibition tied to a new idea of ephemeral. Temporariness, substitutability, provisionality become the new references of architectural modernity nourished by the concept of the reproducibility and seriality of industrial production.

3. Industrial Production and the New Idea of the Beautiful

Considered primarily as a service, the fairgrounds of Palermo becomes the place with which (and on which) to construct a ‘reading’ of Sicilian and Mediterranean productivity, a text in which art and architecture occupy a real role in social life.

Obviously the artefacts of industrial production to be displayed in the exhibition cannot be correlated with either art or architecture, they involve both dimensions because the exhibition method must, through the organization of the spaces and the composition of the materials to be exhibited, provide a pleasant, and in any case, attractive representation. Hence, the Italian word

mostra (exhibition, show) which derives from the Latin word

monstrum: a prodigious, factual or remarkable phenomenon [

1].

Fair exhibitions, in the course of the history of the last century, evolved according to increasingly innovative schemes. Starting from ornamental and illustrative models anchored to the classical tradition of museums, there was a gradual passage toward the search for a pleasant setting for products, intended for a public that can thus identify itself with an interesting place, according to a ritualistic representative form, able to ennoble the ceremonial of the goods displayed (

Figure 2).

The widespread use of draperies, velvets and pompous furnishings, which were seen in the earliest set-ups of international expositions, still denoted a quantitative interest in the goods displayed, without a clear distinction between types of products, in a traditionally furnished environment.

As fairs passed from being general international expositions, to trade fairs, they acquired a specificity of representation benefiting the relationship between exhibited object and exhibition space; the design, in visual and volumetric terms, of the architectural structures allowed an organicity that entered naturally in the updated debate of the artistic avant-garde [

2].

Paul Valéry wrote in The Conquest of Ubiquity (1928): “Our fine arts were developed, their types and uses were established, in times very different from the present, by men whose power of action upon things was insignificant in comparison with ours. But the amazing growth of our techniques, the adaptability and precision they have attained, the ideas and habits they are creating, make it a certainty that profound changes are impending in the ancient craft of the Beautiful. In all the arts there is a physical component which cannot be considered or treated as it used to be, which cannot remain unaffected by our modern knowledge and power. In the last twenty years neither matter nor space nor time has been what it was from time immemorial. We must expect innovations to transform the entire technique of the arts thereby affecting artistic invention itself and perhaps even bringing about an amazing change in our very notion of art.” [

3].

The artist traces, with the utmost rigor, the process of transformation of modern art, introducing the values of temporality and perishability that are proper to industrial structures (

Figure 3).

The history of the industrial process is largely based on perishable material, subject to corrosion, recycling and the same structures conceived for temporary functions, to accommodate specific technological equipment, have a long service life and a much longer obsolescence than common constructions and traditional architecture.

Paul Valéry also praised the new aesthetics of industrial structures, of lines that enhance function and give architecture an essentially mechanical content.

This represented a way out of the neoclassical, International and kitsch styles, and the results achieved in this field by architecture have shown that, despite the first disorientation brought about by the new construction systems, it is still possible to reconcile the necessary with the beautiful, logic with art.

4. Industrial Culture and Classification of Exhibition Spaces

The need to guide the public originates from an increasingly widespread “industrial culture” that has a need to overcome general formulas in order to proceed towards the specific identification of the products. At the same time, the growth of historicism and scientism opens the door to the system of classifications, so that the different categories can be clearly identified. Daniel Lerner states: “

The first test of scientific knowledge is that it must be public and not private, explicit and not “secret,” available in a common fund for use by all who can learn. This test has a sociological derivation as well as a methodological consequence.” [

4].

Lerner induces us to think about the distinction between quality and quantity that animates the debate on modernity. The mechanistic and quantitative universe of 19th-century science, though surpassed in the following era, has in any case left deep traces in contemporary thought.

Modern synthesis seeks to remodel, for a more profitable use, two components of knowledge that can no longer be effectively kept in dialectical opposition. This synthesis is even more evident in the display of trade products.

However, the growing development of technology and science has finally made it clear that “culture” is also industrial culture; indeed, it can be said that this is the culture of today's world, that factories and production sites of all kinds are containers of science, technology, entrepreneurial ability, intellectual and manual competencies, where an immense effort is made which grinds up and transforms man's life and his society (

Figure 4).

Trade fairs are concerned with making this productive process manifest, indicating a path, differentiating categories, by making a selective reduction in the quantities, for a greater quality of information [

5].

Thus, the pavilions were created, according to the idea of a specific identification of the products to be displayed: architectural images that act as relais for the product they host.

The Palermo fairgrounds, from the moment of its foundation to the present day, has been characterized by innovative stand and expositive structures such as the Mechanics, Electricity, Chemistry and Radio Engineering pavilions. It also hosts a small area for foreign countries, as well as the “Furniture and Furnishings”, “Liquors and Perfumes”, “Building and Construction”, ” Food” pavilions, and so on, recycling, adding and replacing structures with other structures, bearing witness to ever-changing industrial cycles in search of a constant updating of the exhibition space.

The approach that results for permanent and transitory structures tends to take into account the accord between thought and language, between artefact and environment, which become so reciprocally assimilated to the point of accepting to speak a common language.

The fair’s architectural components are designed in relation to the exhibit space according to product constants. These develop and accentuate relationships of mimesis and allusion (as for rationalist-style pavilions), but also of illusion and reinvention (as for those in the foreign countries’ area); in an architectural repertoire between the ancient and the contemporary, placing the accent more on classic annotations or, at other times, more on modernist comparisons (

Figure 5).

5. The City of Images

Especially in reference to the years of the so-called “economic boom”, we talk about a consumer society, fueled by an often-uncontrolled culture of images, but the relationship between architecture and image has deep roots [

6]. In 1907, in the founding manifest of the Deutscher Werkbund, the German Association of Craftsmen supported the necessary mediation and convergence of three activities:

Kunst,

Industrie,

Handel (Art, Industry and Commerce). Art related to propaganda for industry brings us back to the previously analyzed value of quality, proposing the ideal, pure visibility of the quality product against the dangerous anonymity of quantity (linked, above all, to industrial scale reproducibility) [

7]. Artistic innovation offers its contribution to technological innovation and the encounter between industrial representation and industrial product is one of the most innovative teaching programs of the Bauhaus school of applied arts, where, in addition, the industrial product has known a formal revival, fundamental for modern design.

The advertised industrial product enters into the culture of the urban image by making use not only of architecture, but also painting, decoration and the minor arts. Light and colour combine thanks to signs, signals, posters so as to alter, mask and overlap architectural structures, generating a process of dematerialization of reality. Representation of the metropolitan urban landscape tends toward the image of the fair, while the urban scene recreated in the fair seeks to use architecture in harmony with advertising images and advertising in general, structuring ephemeral landscapes capable of nourishing the urban mimesis (

Figure 6) [

8].

Cinema, from Fritz Lang to Fellini; literature, from Calvino to Pennac; music, from symphonic to rock, confront the urban scene and its contaminations, so much so that Bob Dylan described in Tarantula (1970):

“Advertising signs that con you

Into thinking you’re the one

That can do what’s never been done

That can win what’s never been won

Meantime life outside goes on

All around you.”

While Gillo Dorfles wrote in 1964: “All the multiform images that surround us, giving us warnings, precepts, flattery (the images of road signs, movie posters, political posters, illuminated signs, etc.), actually constitute a new iconographic panorama for our times, but they also represent the new mythical gods who constantly watch over and assist us, when they do not seduce and hypnotize us. (...) My conviction is that there is much to be learned and to be gained from the presence amidst us of these “New Icons”; so much so that by relying on them, we can achieve a balanced restructuring of our civilization.” [

10].

6. Representation, Information, Propaganda

When, more than 70 years ago, the Fiera del Mediterraneo inaugurated its program for the promotion of trade and communication, this was related to the user through what can now be termed an “archeology of the image” of industrial products.

In the archives of the organization we find the origins and history of the representation of the products of its trade fairs and the first elements of its corporate image.

A revaluation of those materials allows us to investigate and reflect on these representations, to attempt an interpretation on thematic lines, thus retracing the significant moments in which the product-image accompanied the product exhibited, with particular attention to the formation of the visual message’s composition [

11].

Borrowings and contaminations represent the evolutionary supporting structure of the graphic communication of industrial products, where the experiences of the figurative avant-gardes and the legacies of the academies converge, until graphic exhibition objects become a large independent laboratory of visual languages (

Figure 7).

The different aspects of graphic design and visual communication, intended for such a large audience as that of a fair, must be disseminated through several different channels of mass communication such as publications, television, cinema or the streets, considered a primary exhibition space. The fundamental principle governing the process of graphic communication is that derived from the mathematical theory of information, which states that communication is always between a subject who conveys a message and a subject to whom the message is conveyed. In this case, the graphic image plays a primary and diffusive communicative role: at the service of a social objective, of publishing, and also in the more ordinary field of advertising billboards [

12].

At the beginning of the 1970s, in the years defined as those of the Italian Artistic Metamorphosis, graphic art also appropriated the third dimension, becoming architecture itself: from the configurations of prospective views, to the ‘skin’ of buildings which thus became a means of communication for propaganda messages, to ephemeral set-ups using impressive three-dimensional structures for the most important product sectors [

12].

Here was an answer to the attentions of the productive and consumerist world for packaging, gadgets, advertising objects. The metamorphosis of the 1960s and 1970s can be understood as a small, modern renaissance: seen in architectural design, in interior design, in environmental art.

In Italy this is also evident in Guttuso’s figurative painting as well as in Burri’s material-based pictorial art; and again in the neorealist cinema of Visconti and Rossellini, in the search for an urban identity through the use of the colours and the signs of mural paintings, following the phenomenon, marked by an evident Anglo-Saxon influence, of supergraphics.

It is a matter of pointing out the subtle connection that marks architecture and its formatting, compositional code and visual code, in a field where the culture of design takes the form of a culture of images [

13].

7. Synthetic, Astonishing Language

The increasing interest of the public and the press for international exhibitions and trade fairs since the end of the 19th century has encouraged the creation of a graphics for specialized magazines for that becomes an informational support for companies’ exhibitions (

Figure 8).

Especially for the most experienced companies, the exhibition of products in the fair develops as a synthesis of industrial culture, according to an ideal projection of an expanding company and of the relationship with the user.

The designer-stand assembler is thus entrusted with the task of expressing this message in a synthetic way, enriching it at the same time with experimental research goals, which are also measured by the resulting effect on the customer.

One of the major European industries at the beginning of the 20th century, AEG, began collaborating with architect Peter Behrens in 1908 and the results were revolutionary enough to mark a foundation step for the encounter between industry and user.

The visual effect of the individual artefacts was such that they themselves could take on the capacity of dialogue with the public in an exhibition space.

For what regards exhibitions, this is the case of the “Regina” trade fair stand realized in 1924 by Herbert Bayer, a professor at Walter Gropius’s Bauhaus School of Applied Arts, in which experiments with integrated communication techniques were carried out: film projection systems, soundtracks, lights and kaleidoscopes. And then Le Corbusier with his

Pavillon de

l'Esprit Nouveau; Marcello Nizzoli with the Chemistry Pavilion at the 16th

Fiera di Milano in 1935 for Montecatini. And finally, the entirely Italian case of the collaboration between Egidio Bonfante and Adriano Olivetti, the artist and the entrepreneur, in a very high-profile dialogue for an avant-garde production of products supported by coordinated images [

11].

8. A Manifesto for the Mediterranean

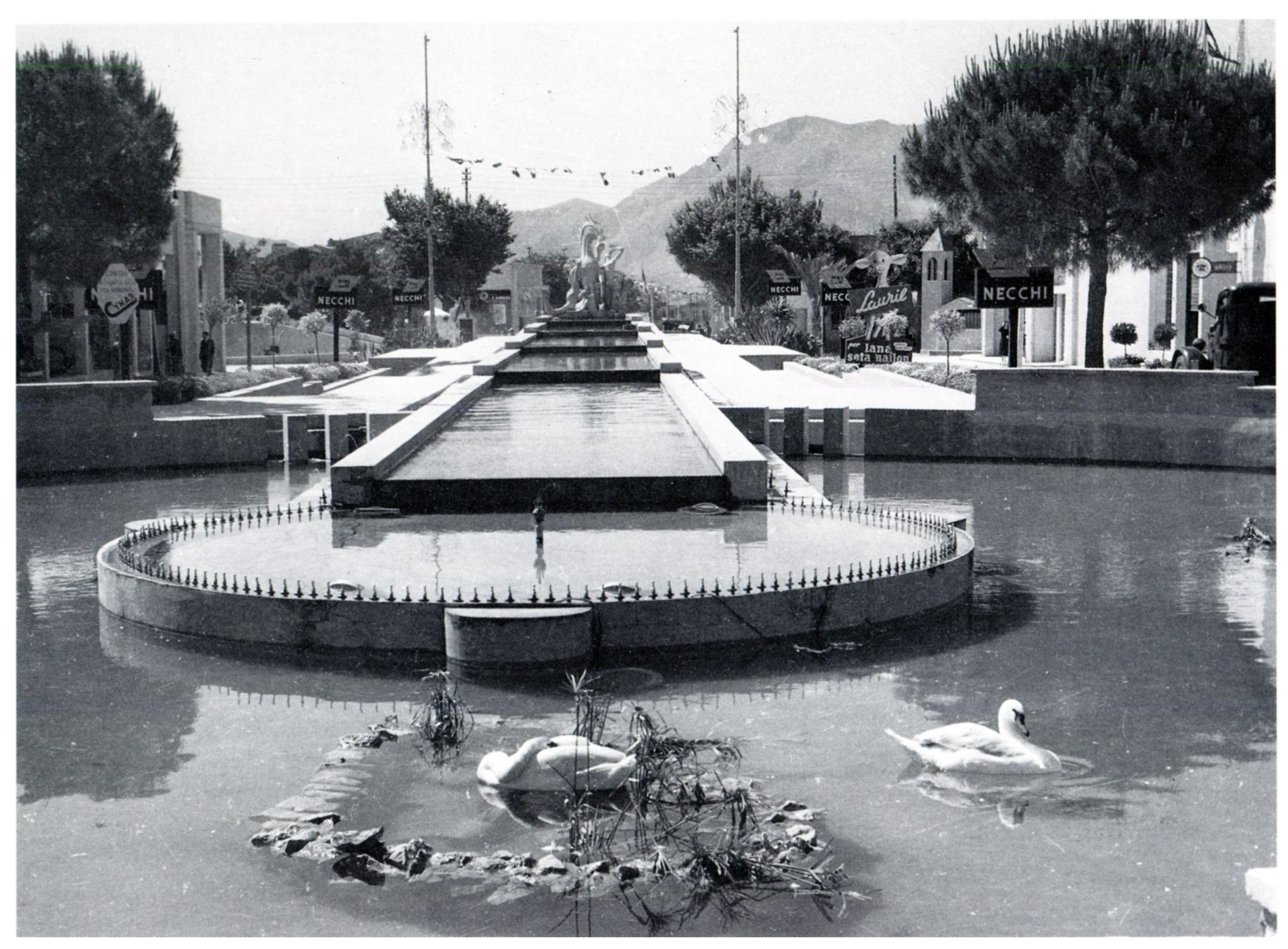

The architecture of the

Fiera del Mediterraneo in Palermo, in its original layout, stripped of its signs and stands, takes on a formal dignity recognizable for its style and context. The compositional aspects of the pavilions are constantly measured in terms of tradition, regionalism and rationalism, sometimes insisting more on one or another aspect, since the first purpose of a fair lies particularly in the communication of its own image. Visual communication calls for strong signals and the fair incarnates the sense of an image laboratory through the representation of its pavilions, its decorative elements, and of all the structures that characterize the district (

Figure 9).

In the first project and in the expansions realized up to the 1970s, the Fair alternates references to traditional Mediterranean figures and rationalistic and organic architectural styles, for a fair conceived as a visual machine consisting of concrete spaces and ephemeral apparatuses [

11].

It lends itself to an analysis focusing on its dual image: one, “external” because urban, territorial, Mediterranean, and another, “internal,” unfolding amidst the boulevards, the pavilions and exhibits on display. For both images there was a project, a set-up.

In the years of post-war reconstruction, the Fiera del Mediterraneo represented a great hope for Palermo. The city, still ravaged by the bombings of World War II, had not had time for a significant recovery with an architectural and urban revival.

So when in October 1946, just after the end of the war, the fairgrounds was inaugurated, it almost seemed that the venture of an economic-commercial and architectural revival could quickly invest even the entire city. But unfortunately this was not the case.

The fair was, however, the site of dreams and hopes, even simple and naïve ones, for all those who looked to the world of professions and innovations.

Everything was exhibited in spaces which were simple, yet studied with considerable care in the articulation of voids and volumes by architect Paolo Caruso. He had the responsibility of managing the project coordination of the whole district in the decentralized Piano delle Falde quarter, on the edge of a Palermo blackened by bombs. Other architects, such as Cardella and Epifanio realized important works, and the scenography of the furnishings for the boulevards and the entrances was carried out by the artists Sparacino, Amorelli, Bottari, Oliveri, Carnesi and Marzilla.

The fairgrounds’ layout represents a visual machine comprising architecture and scenography according to the conditions imposed by the reality of the moment. For this reason it can be said that the experimentation adopted in the design of the

Fiera del Mediterraneo represented an interesting laboratory for modern production in Palermo (

Figure 10 and

Figure 11).

The fair, until the 1990s, was a place much loved by the Palermitans. Their attendance, dictated by regular fixed appointments, had entered into the habits of several generations. A microcity of the ephemeral called on to showcase its very opposite, that is, industry and handicrafts, the most concrete of anything offered by international and local production at the time. In an archive—no longer in use—an extensive photographic repertoire created by the most acclaimed professionals in the city was kept, in which not only the stages of growth and modification of the constituent parts of the district were documented, but also the origins and the evolution of the brands of many local, national and international products, protagonists in the history of the post-war period and the accompanying economic boom.

The fair today has remained a victim of its own ephemeral nature. Exhibition standards have changed, strengthened by stringent regulations not respected in the now-obsolete structures. Today, those architectural works that survive demolition are mostly denatured by superfetations and intensive adaptation interventions that have, in fact, substantially altered their former image.

In fact, this is a case of industrial archaeology in search of a difficult-to-recover identity. But this place can also be seen as an opportunity, not only for looking back to a still recent past that can help us to better understand our own reality, but also for finding a way to rediscover its meaning.