Abstract

This paper is part of the disciplinary framework of drawing. The forms of symbolic representation of Naples are explored, with particular attention being given to the construction of the visual image on an urban scale. The theme of the image represented here lies in the risks of the uncritical use of the image and, above all, of technological innovation when it only affects visual communication operations through the vacant mediatic use of the architectural envelope. The consideration between the aim of the image content and the risk of its (as well as the structure’s) spectacularization is the ethical goal of this paper. Firstly, the experiences of street art recently carried out in cities, which, renewed in the aesthetic language, have produced significant images aimed at the recovery of abandoned buildings and/or the socio-cultural renewal of degraded suburbs) are discussed. Secondly, the two project proposals in the field of graphic design, aimed at regenerating the historical and/or social roles of specific urban contexts and building visual images capable of building identity and belonging to the community are also described.

1. Introduction

This paper is part of the disciplinary framework of drawing. It explores the forms of symbolic representation of Naples, with particular attention being given to the construction of the visual image on an urban scale. The theme of the image represented here lies in the risks of the uncritical use of the image and, above all, of technological innovation when it only affects visual communication operations through the vacant mediatic use of the architectural envelope. The consideration between the aim of the image content and the risk of its (as well as the structure’s) spectacularization is the ethical goal of this paper. First, the experiences of street art recently carried out in cities, which, renewed in the aesthetic language, have produced significant images aimed at the recovery of abandoned buildings and/or the socio-cultural renewal of degraded suburbs) are discussed. Second, two project proposals in the field of graphic design, aimed at regenerating the historical and/or social roles of specific urban contexts and building visual images capable of building identity and belonging to the community are also described.

2. Naples, City of Numerous Images

Naples has always been imaged and represented through the use of multiple languages as well as various forms of communication and technology. Primitive history interpreted it with the mythical image of the siren Parthenope, who, drowned by her unrequited love of Ulysses, was carried by the sea currents between the cliffs of Megaride. Found by fishermen, she was revered as a goddess. The myth tells of how the siren’s body dissolved and transformed into the morphology of the city, known since then as “Parthenopean” (Figure 1a).

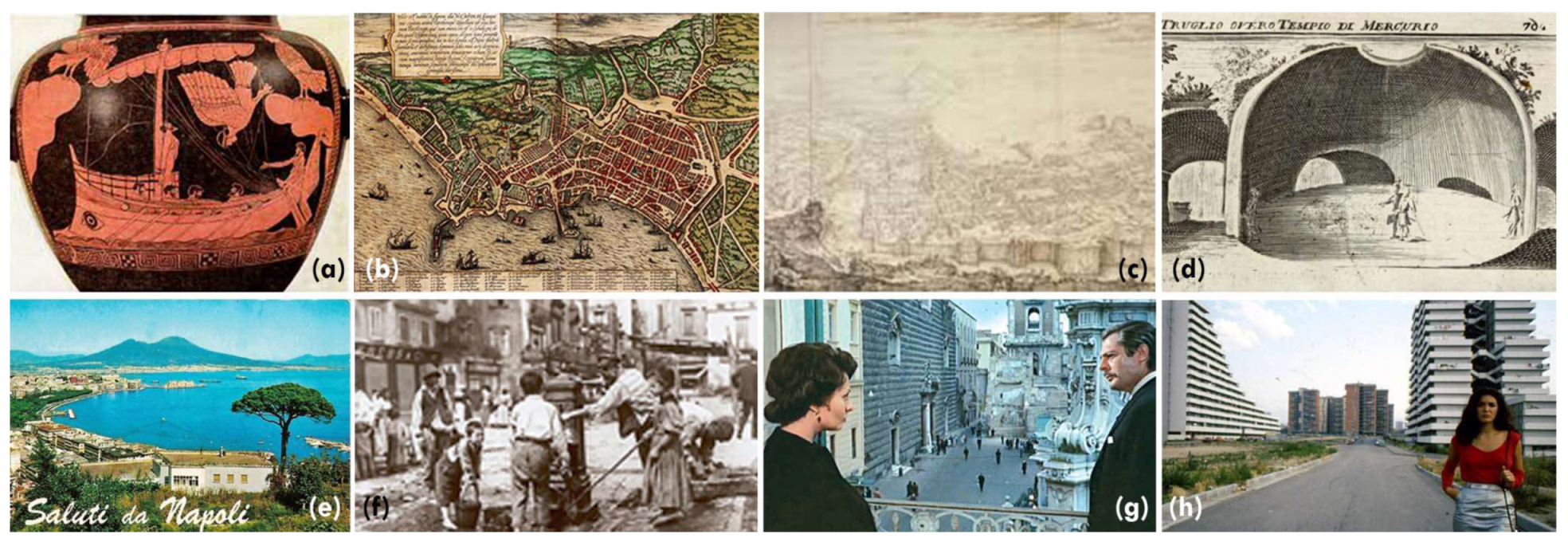

Figure 1.

(a–h) Naples, city of numerous images: mythological, vedutistic, touristic, social, emotional.

A sea town with an ancient history, natural beauties and artefacts, as well as multiethnic cultures, Naples is one of the few Italian cities in the late sixteenth century North-European Atlanti di Città. The image is surrounded by the sea, with it representing the extraordinary beauty of the natural places as well as the important architecture of a city with a history spanning over two thousand years. The view is geometrically constructed with only scientific knowledge. It is not visible from any real point of view. It is, therefore, a mental image. A graphic rendering that fascinated noblilty and the wealthy bourgeois, collectors of views of unattainable places, of which the contexts are imaginative (Figure 1b).

This iconographic model was replicated over the centuries, even when the city was transformed. Conversely, the unique models offered unpublished images. In addition to the traditional frontal view of the sea of Naples, there were lateral views as well as from the north looking out to the sea, which, if related to each other, stimulate the imagination (Figure 1c). The eighteenth-century trend of the Grand Tour, along with the creation of the guided visit of the city and surrounding areas (such as the Flegrean area, a highly sought after archeological destination by foreigners) introduced urban and/or architectural scale views. The visual image changed dramatically and simulated the representation of places perceived to be fit for humans. Thus, what the eye sees is closer to that of the painter than that of the cartographer (Figure 1d).

With the advent of photography, there was the proliferation of panoramas that, as in pictorial vedutismo, created the most famous postcard image in the world of Naples: a landscape of extraordinary beauty and harmony between the built and nature, which for a long time would represent the city in the collective imagery (Figure 1e). The versatility of photographic technology made it possible to develop new ways of looking at the city. The Alinari brothers realised a fascinating photographic heritage of Naples in which the architectures are the scene of a varied social landscape. Technological objectivity questioned the previous images. Cities and portraits were no longer wonderful to imagine, but a reality almost at the limit of decency. Buildings and roads were mute witnesses to a Naples that was significantly different from the beautiful tourist postcards. The images rather crudely showed the real social situation (Figure 1f).

Cinematography revolutionized all the previous image recording devices, with it producing real-life visual narrative shapes as well as a greater manipulation of emotions. It is worth mentioning two cult scenes from Neapolitan cinema: the fixed shot of the open window on Piazza del Gesù Nuovo, where the façade of the church of the same name, the bell tower of Santa Chiara and the spire of the Immaculate are the silent backdrop to the touching dialogue between Sofia Loren and Marcello Mastroianni in Matrimonio all’italiana (1964, directed by Vittorio De Sica) (Figure 1g) and the moving image of a young Marina Suma in Le occasioni di Rosa (1981, directed by Salvatore Piscicelli), while crossing one of the most critical popular neighbourhoods of the city, Scampia, where the powerful and impressive Vele are the backdrop, denouncing the violence endured by the inhabitants when the architecture becomes nothing more than a dormitory (Figure 1h).

3. The Domain of the Visual Appearance

The IT revolution is one of the main causes of the extensive modification process, with it having involved contemporary culture in the incredible development of the visual image. Gombrich stated in 1982: “We live in a visual age. From the morning to the evening, we are bombarded with images [...]. And in the evening, to relax, we sit in front of the television, the new window on the world, to observe a flicker of images [...]. Illustrated books, postcards and slides accumulate in our homes as travel souvenirs, along with private family memories. No wonder, then, if anyone has said that we are at the threshold of a new historical era in which the image will be in the written word. In the light of this statement, it is of the utmost importance to clarify the potential of the image with respect to other forms of communication, to ask what can and what cannot be done better than written or spoken language” [1] (p. 155).

In comparing the effects of oral and visual narratives, Orazio in Ars poetica stated that “the spirit is stimulated more slowly by the ear than by the eye” [1] (p. 158). In support of this, recent scientific studies on animal behaviour (including those of the ethologist Konrad Lorenz [2]) show that, for survival, animals (which includes humans) are genetically programmed to better react to visual signals, so much so that Rudolf Arnheim in his studies of visual perception stated that “movement is the strongest visual appeal of attention” [3] (p. 303) since motion equates to a change in environmental conditions, to the approaching of a danger or a desirable prey. Without resorting to other sources, this is sufficient to justify the choice of technology increasingly oriented to a visual, fixed or mobile visual communication as the privileged medium. Based on technological innovation and as highlighted by Gombrich, the Internet can now be considered the new window on the world, with it producing a bombardment of discontinual spatial and temporal images (no longer on paper or television), which accumulates in immaterial homes (smartphones, computers, social networks, etc.).

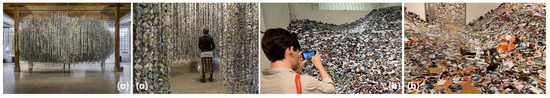

Recent art installations, Roberto Pellegrinuzzi’s Mémoires (2015) and 24 h in Photos by Eric Kessels (2013), denounce this accumulation. In the first, 275,000 photographs of daily life (compulsively taken by the author based on the obsolescence of the digital camera) were assembled in the form of a cloud in which to dive into. The photographs represented the metaphor of the large number of images accumulated in our brain like a cloud storage system (Figure 2a). In the second, thousands of 10 × 15 cm prints of images uploaded to Flickr in a 24-h period filled a room to the ceiling, making the intangible tangible (digital photographs of emotions and memories). Thus, demonstrating how in contemporary society, the moment of intangible sharing on the social network of experiences is more important than the moment itself (Figure 2b).

Figure 2.

(a) Mémoires by Roberto Pellegrinuzzi; (b) 24 Hours in Photos by Eric Kessels.

In the era of video projection technology and multimedia communication, the city has also become a new window on the world, an urban-scale image transmitter. Invoking the futuristic atmosphere of the film Blade Runner, or the Tokyo or Shanghai neighbourhoods (which create a globalized image-driven world), referring to Peter Zennaro in Architettura senza [4], in this climate, contemporary architecture is increasingly focused on the ephemeral and epidermic dimension of the technologically communicative building, with the risk (according to some) that in the future its theoretical foundations may become marginal until they are dematerialized since they are subjected to an idea of post-metrology consumption and simulation. The focus is on the interaction between architecture and visual communication for the restoration of urban landscapes whose physical limits include media events in which the artistic dimension is increasingly present. Technology is innovating and influencing architecture by reducing physicality and durability in favour of the surface and the ephemeral.

Artistic languages are also geared toward new communication tools, with video having activated a continuous creative process, merging multiple forms while also integrating figurative art, literature, music, dance, theatre and cinema. At the same time, the advertising market has also realized the communication skills of video as well as the Internet of things through the widespread use of video screens and graphical interfaces. Technology is intimately modifying the modus vivendi of society, both its public and private spaces, with WJ Mitchell [5] having stated that the home has now assumed a new meaning: no longer sheltering in an architectural space but connecting our nervous system to electronic systems, which are in close proximity. However, in this massive visual communication scenario, it is true that the objective criticisms are, for example, the need for large amounts of energy to support the information society. In this sense, as Galimberti said, “without the technical doctrine man would not survive” [6] (p. 715), solutions to this and other more ethical issues could be non-technological but suggested by the investigative thinking of art, which has always raised the real questions. It is in this cultural climate of uncertain thinking that street art or urban art comes to Naples and realises new images that, adapting to the architecture as well as the city, promote new identities, opportunities and desire for social redemption.

4. Neapolitan Street Art as an Image of Public Art

Street art is a form of creative expression that has recently become more widespread, with different attitudes and impacts depending on the contexts where it can be found [7,8]. In Italy, it has established itself above all in the suburban neighbourhoods of the major metropolitan cities with significant social and, sometimes, economic impacts. In this perspective, this paper analyzes what is currently happening in several Neapolitan neighbourhoods. Thanks to the initiatives of a number of associations, several public residential building complexes, that are suffering from both physical and social degradation, are re-capturing identities thanks to the powerful social charge of the murals that are not only on the buildings but also in the underground Linea metropolitana 1. The line runs from Piazza Garibaldi to Piscinola-Scampia, along which there are the five ‘Stations of Art’ that have inaugurated a new philosophy of conceiving railway architecture, combining visual art with architecture, while also proposing the stations as an opportunity for urban regeneration. In these five stations, the names of the artists are significant and consistent with the financial resources allocated, however, on the outskirts of the so-called ‘Viaduct Stations’, there are spontaneous events sponsored by the current municipal administration. Art becomes the instrument of socialization and the assertion of human rights in respect of cultural, physical and environmental diversity.

World-class and national street artists have recently been involved in social projects in Naples. The Neapolitan artist Roxy in the Box is well-known throughout the city for using narrative stencils that feature famous art characters (Chatting, in the Quartieri Spagnoli) and star system (Vascio Art, in the streets of the historic centre) to activate sharing and reciprocity processes with the inhabitants of the popular neighbourhoods. Roxy’s language is popular with blazing colours, real-life human figures and Neapolitan scenes. From PoPolari to PoPolani is the motto of Vascio Art. The art project makes use of the Dolce & Gabbana media event that was held in Naples (2017) and along the street level flats portrays the stylists (sitting and eating melon, drinking beer) and the actresses as models: Bellucci is coming out of a flat with a rubbish bag; Campbell is sweeping an alleyway; Kidman is riding a Vespa; Loren and Madonna are selling sweets; Rossellini is a shopkeeper (Figure 3a).

Figure 3.

(a) Vascio Art by Roxy in the Box; (b) The Cardillo of Scampia by S. Jung and P. & H. Schweizer.

In 2009, Simon Jung and Paul & Hanno Schweizer painted, with spray cans, a giant cardillo in Scampia (a peripheral and popular neighbourhood), which has almost disappeared. The artists realised The Cardillo of Scampia project with the inhabitants of the area. The bird is depicted free and in flight with its wings open. This is the opposite of the real and illegal image of the cardillo in a cage, a victim of local poaching. The bird was drawn in anamorphosis on several balconies and walls of the flats of one of the Vele, sadly known as a place were illegal drugs were sold. Consciously, the Vela that was chosen can be seen from the square in Scampia and Mammut, the cultural centre for the young children and adolescents of the neighbourhood. The image that represented the project shows three boys riding the bird (sitting on the parapet) in the symbolic act of heading towards new destinations (Figure 3b).

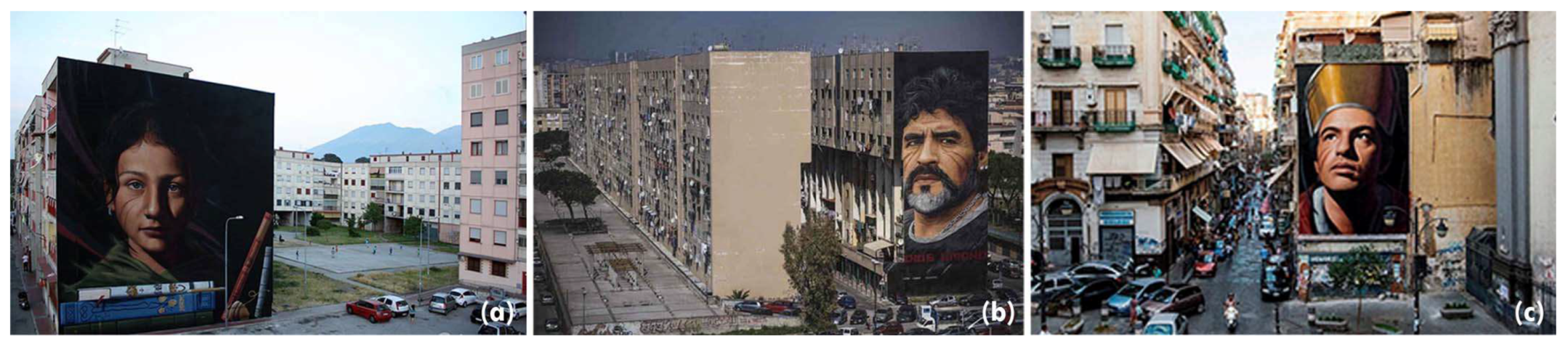

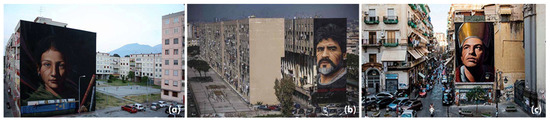

In the peripheral neighbourhood of Ponticelli, on the front of a 20-m social housing building, there is the mural by Jorit Agoch entitled Ael, Tutt’egual song’e criature, inspired by the song by Avitabile (Figure 4a). Painted during the last Giornata Internazionale dei Rom, Sinti e Caminanti to raise awareness about ethnic-religious integration, it depicts the face of a dark skinned young Rom girl (Ael) with the beauty of a sixteenth-century portrait, looking into the eyes of those who she observes. On the lower edge, there are the symbols of integration between culture and tradition (books, pencil, spinning top); on her face, there are two signs that represent both the signature of the artist as well as the symbol of equality between different ethnicities.

Figure 4.

Jorit Agoch: (a) Ael, Tutt’egual song’e criature; (b) Dios umano; (c) San Gennaro.

Agoch painted a more impressive portrait in the nearby San Giovanni neighbourhood: the contemporary Neapolitan legend, Diego Armando Maradona (Figure 4b). At the bottom of the mural, there are the words Dios umano; on his cheeks, there are the usual two signs that the player defined as the symbol of belonging to “one single human tribe”. With the aim of redeveloping the neighbourhood, the artistic project at Ponticelli was promoted by INWARD, Osservatorio sulla creatività urbana (supported by the Rotary Club, National Anti-Discrimination Office, Ceres); while the project in San Giovanni was funded by private organisations as well as the municipal office for logistic and organizational support.

In the centre of the city, Agoch painted another evocative mural, in reference to the icon of the patron saint of the city, San Gennaro (Figure 4c). Located at the entrance of the popular Forcella neighbourhood in Via Duomo, a few steps from the Cathedral, the San Gennaro Treasury Chapel and the crypt with the relics of the saint, with a symbol of the Bishop San Gennaro (the yellow miter), the face has a lay inspiration. In an interview, Agoch stated that the face was that of his friend, a young worker in the neighbourhood called Gennaro [9]. On the other hand, others recognize the image as Nunzio Giuliano, a member of a drug trafficking clan in Forcella, who left the clan and was killed for speaking against the Camorra [10].

In the degraded neighbourhood of Materdei, drawn on the back of a building in Salita San Raffaele, there is a 15-m high mural, representing the myth of the mermaid Parthenope. The work, the gift of the sophisticated street artist Francisco Bosoletti, was realized with the approval of the local residents to support the initiative Materdei. Per R_esistere ci vuole pure la bellezza. The highly refined picture represents a fine-looking, proud, thoughtful woman, who is half-fish and half-bird, wrapped in leaves and feathers (Figure 5a).

Figure 5.

Francisco Bosoletti: (a) Parthenope; (b) La donna del giardino; (c) Le ombre di Napoli.

Bosoletti signed another two works in Materdei for the Il Giardino Liberato project. Residents of the neighbourhood, having occupied and cleaned up the garden of the former convent of the Teresian Sisters, transformed it into a cultural centre. The symbol of spontaneous change is represented by two beautiful images: La donna del giardino, on the wooden doors of the exterior of the convent, depicts a face hidden by the leaves in the act of showing itself (Figure 5b); Le ombre di Napoli, in the former convent, depicts a female face as a metaphor of a city that is indifferent both to its beauty (expressed in the green leaves that gently cover it), as well as a pair of black hands threatening to grab hold of it (Figure 5c).

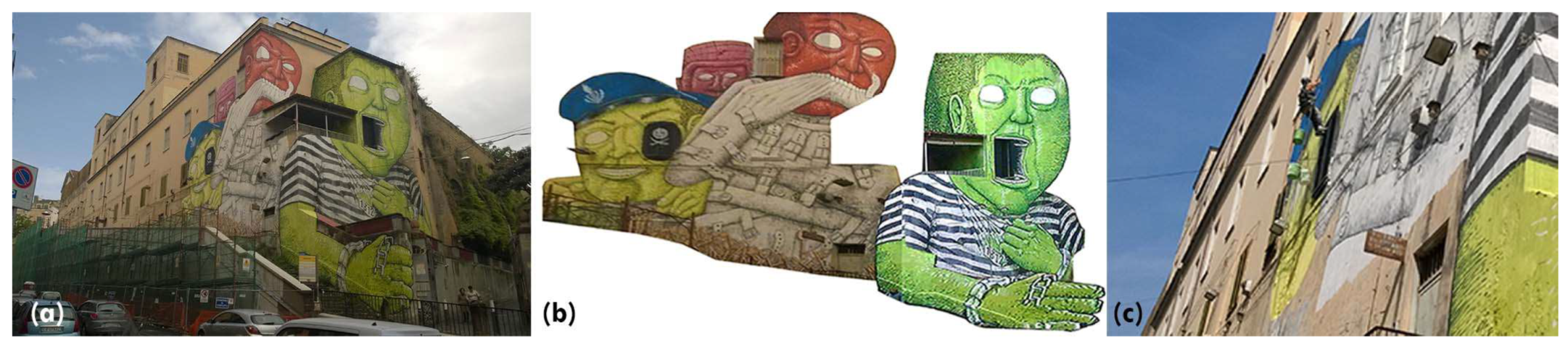

In Materdei, another urban work of art for the spontaneous re-acclimatization of abandoned sites is signed by Blu on the walls of what was origanlly the monastery of Sant’Eframo Nuovo, transformed into a prison mental asylum and since 2015, a city space managed by the association Ex OPG Occupato Je so’ pazzo. Like Il Giardino liberato project, since 2016, theEX OPG Occupato has been recognized by the local adminstartion as a common assest for the socio-cultural services of the neighbourhood. The name Je so’ pazzo refers to the stories of those who lived here segregated, undergoing therapeutic treatments at the limit of human rights. Blu, one of the top 10 street artists in the world whose works appear on the walls of the main metropolitan suburbs, represented this with an angry image that recounts of enclosure, containment and liberation (Figure 6a).

Figure 6.

Blu: (a) Murales on Ex OPG Occupato Je so’ pazz; (b) drawing unfolded by Vincenzo Cirillo; (c) Blu.

The scene consists of human figures (two prisoners and a prison guard) with empty and disturbing eyes, that cover the two orthogonal fronts of the building. The projections are at different heights and there are two windows that in the drawing become an open mouth and a blindfolded eye. The first prisoner, with acid green coloured skin, is on the short side of the building and is the main attraction of the mural for those coming from the crossroads at the entrance of Via Imbriani. With his eyes and mouth wide open, the prisoner is pulling at his striped prison shirt and has broken the chains on his wrists. On his shirt, there is a number: 1312, acab, all cops are bastards. The second prisoner has red skin and is drawn on both sides, wearing a dreadful straitjacket, that he is biting at. The prison guard, green, is on the long side of the building and is represented by a blue cap and a pirate patch over one eye, with a sarcastic grin while holding a piece of wire with the cell keys on it. Behind him there is a fuscia coloured human figure.

For the realization of this mural, Blu used tempera paints and hung from the roof of the building while wearing a moving harness (Figure 6c). The work, at present still incomplete, will continue along the entire front of the building. Although still unfinished, Blu’s mural has an overwhelming impact due to the strategic position on the road, the graphical synthesis and expressive power in documenting prison mental asylums, along with the clever geometric control of prospective construction on multiple wall surfaces and at different levels.

Regarding the prospective construction of the mural, a graphic operation was performed to ‘unfold’ the image onto a single plane, where the drawing is made up of several parts located on several orthogonal surfaces. Based on the architectural surveying of the planimetric and altimetric outlines of the foreheads of the Ex OPG, it confirms a highly creative imagination on the part of the artist in adapting parts of the narrative to space elements and architectural components, such as the aforementioned windows as well as the roof and the wall with the neighbouring residential park. At the same time, the comparison between the unfolded drawing and the one on display highlights the ability of Blu to dominate the configuration of the prospective scene. Blu has expertly managed not only the material execution of a large sized mural, but also the control of the proportions and the continuity of the signs. The final perceptual effect gives parts of a single image, located on separate planes, as three-dimensionally continuous to form the head, chest and arm of the green prisoner as well as the head and sleeve of the straitjacket of the red priosner (Figure 6b).

The examples show how the concept of street art has changed [11]. Neighbourhood and/or local administration initiatives continue to promote these projects, with it no longer being considered as defacing walls but rather as a form of decoration to promote the sense of belonging to peripheral and degraded places, activating forms of redevelopment, while aslo stimulating cultural tourism. The artistic language of the mural has therefore changed: from a violent and abstract sign in search of a new narrative aesthetic that, without denying the ideological matrix of social denunciation, proposes the image of beauty in places where there would be none. In addition, these images are not open to the physical environment but adapt to architectures and roadside visuals to favour a conceptual synthesis between the memory of the places and new looks over the city.

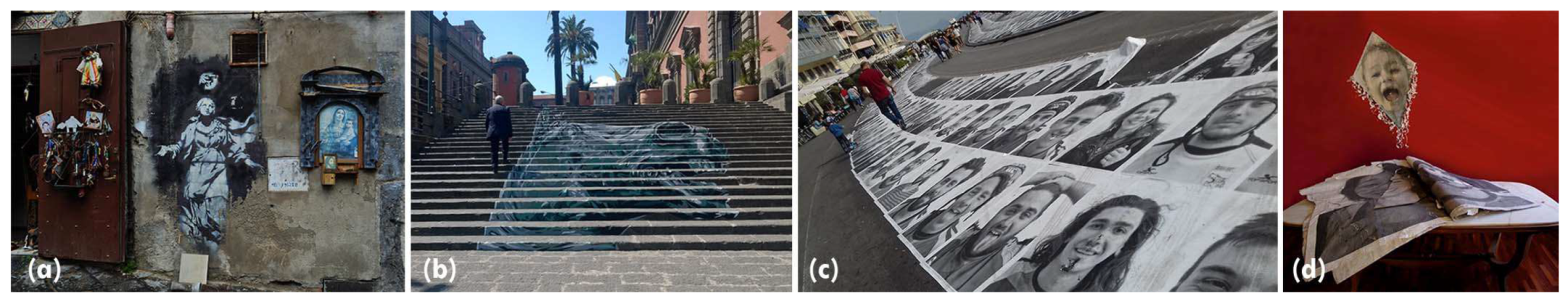

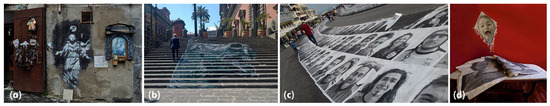

Paradoxically, the increasing presence in urban communities and world-wide success has led street art to the major auction houses: commissioned by art collectors to steal the mobile works of art, such as those of Bansky, which are torn from the walls. Even in Naples, the stencil made by Bansky has been the subject of unusual attention. For years in Piazza dei Gerolomini between votive altars and street level flats, it is an image of Sant’Agnese’s between tradition and topicality: eyes looking towards the sky, with a gun at her head (Figure 7a). Upon a restaurant recently opening next to the stencil, the image has been put under a glass case with notice that reads: “Bansksy’s work, guarded by the Pizzeria del Presidente and Agostino o’ Pazzo”. It is protected, not because of the social meaning of the image but rather due to it being a consumer attraction [12].

Figure 7.

(a) Bansky; (b) David Diavù Vecchiato; (c) JR Artist; (d) Rita Esposito & Daniele Galdiero.

The growing interest in street art has also extended to the organization of media events. For the presentation of Donatello’s horse’s head at the National Archaeological Museum of Naples (April 2017), the organisers invited David Diavù Vecchiato, who painted in anamorphisis on the steps leading to the museum entrance, a horse’s head (Figure 7b). Similarly, at the first edition of the Festival Sky Arte (May 2017), the French artist JR participated with a street art photography work entitled INSIDE OUT. Napoli: il Rinascimento parte da qui. Realised in the artist’s usual style, the project photographed the faces of 3000 Neapolitans who, “putting their faces”, participated in supporting a message of belonging to a community: “Naples is a world. Naples is a mental state. Naples is an attitude. Naples is the place where it is possible to witness vivacity, along with the cultural and social contradictions of the city. The Neapolitan faces strongly support the fact that the cultural renaissance can only start from here” [13].

Printed in a large format, the images covered the promenade of Via Partenope, which from above appeared as a sinuous line formed by countless black and white photographs (Figure 7c). The enthusiasm was varied: there were those who looked for their own proud image of belonging to the community and took a selfie; those who photographed the photographs; those who walked on them; those who were reluctant to do so. Among them, there were the Neapolitan architects-artists Rita Esposito and Daniele Galdiero who, after the event, collected the torn and dirty images. With the pieces, they created a collage of unreal faces, realised a book Vedi Napoli e poi … vola! and participated in the Biennial of the Book of Artists (Naples, Castel dell’Ovo, August 2017, organised by Giovanna Donnarumma and Gennaro Ippolito). After browsing the fragmented images of the virtual Neapolitan faces, a kite made from the whole face of a young smiling girl flies away from the book. For Esposito and Galdiero, “Man does not want [...] to be bundled, glued, put on the floor and walked on, torn [...] even when his image is a symbol, a piece among other pieces, an icon among icons, a multiethnic and multicultural unicum, Man does not stand for it, and flies!” [14] (Figure 7d).

5. Urban Identity and Graphic Design for Visual Communication

In relation to the relationship between technological innovation, media communication, urban context, identity, social affiliation and the role of street art as an opportunity to redevelop the city through images drawn on roads, walls and other visible surfaces, two meta-projects have been carried out in the field of graphic design.

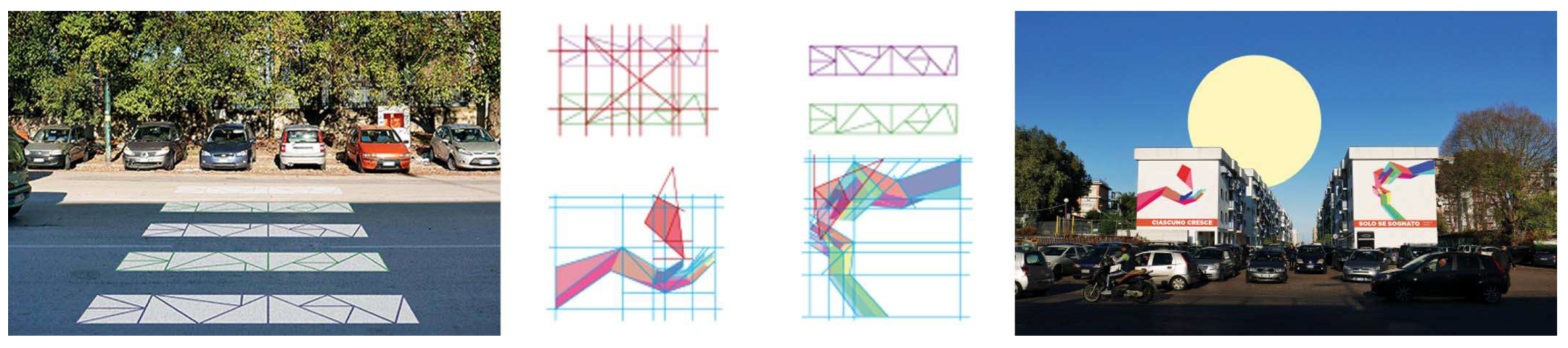

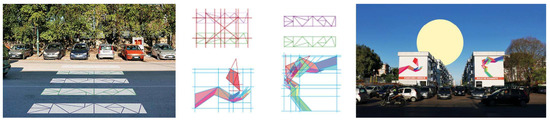

Ciascuno cresce solo se sognato is the title of the proposal consisting of video-graphic installations for the urban regeneration of the aforementioned Scampia neighbourhood. Considering the objectives of the next Memorandum of Understanding between the Municipalities and Universities (under the scientific coordination of the author), the proposal is integrated with active association projects to redevelop the Chiaiano underground station. The idea is the concept of public art and interactive processes involving architects, designers, artists, residents, administrators, politicians, financiers, construction companies, associations, institutions, as well as private investors. The project is based on a site-specific study, with the idea that it is a unique space in the context that is created around it. The aim is to represent through images the values of collective belonging by integrating identity, environment and sustainability. The social dimension of the project is based on the will of the local community to redeem Scampia and the Vele from its collective negative image. The project idea starts at the exit of the Scampia-Piscinola underground station on Via Zuccarini and traces out a route that crosses Via Gobetti, the Vele and arrives in Piazza Papa Giovanni Paolo II, incorporating street art works throughout the territory. The graphic installations consist of a visibility intervention of the urban furnishing elements for aesthetic, functional and social purposes.

The functional aspect comes from observing the context. The Scampia-Piscinola station is a connection node with Naples Central Station and the Northeast Naples underground line that goes to the provinces of Naples and Caserta. In the small area in front of the exit of the station, there is a significant flow of vehicles (with the unnecessary transit and/or parking of those waiting for the arrival of the passengers) and pedestrians (with it being dangerous to cross the road to reach the bus stops). A temporary parking area for motor vehicles and a visual reconnaissance for pedestrian crossings and road signs have been planned. The video-graphic installation becomes an identity portal for the rebirth of the neighbourhood, with the projections being on the facades of the two buildings in Via Gobetti. The images, also produced by known and emerging street artists, will give information on upcoming cultural, artistic, social and productive activities in the neighbourhood when leaving the underground station. This visual communication is part of the municipal plan, which plans to make the remaining Vela (after demolishing the others) an attraction for the whole city.

The meta project will be carried out by the young designer Sara Auricchio, who for the inaugural event has thought of a graphic solution inspired by contemporary street artists (Roadsworth, Christo Guelov, Clet Abraham), which have a strong visual impact on road signs (signs and pedestrian crossings) to draw the attention of pedestrians and drivers. Auricchio's graphic style is geometric and colourful, in continuity with what the street artists and associations have already realised on the exterior of the Scampia-Piscinola underground station. The proposal includes asphalt adhesives (so as not to break the highway code) and removable posters for graphic images placed on the buildings pending the feasibility plan for the technical video installation project. The graphic image created by Auricchio is inspired by a stencil, now discoloured, (already placed by the associations on a Vela as a symbol of rebirth), with a quote by Danilo Dolci, Ciascuno cresce solo se pensato. Auricchio accompanies the quote with a drawing of hands that share an object, entrusting the representation of a gestural expression (nonverbal communication form), evoking an act of solidarity (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Scampia, Ciascuno cresce solo se sognato (graphic design by Sara Auricchio).

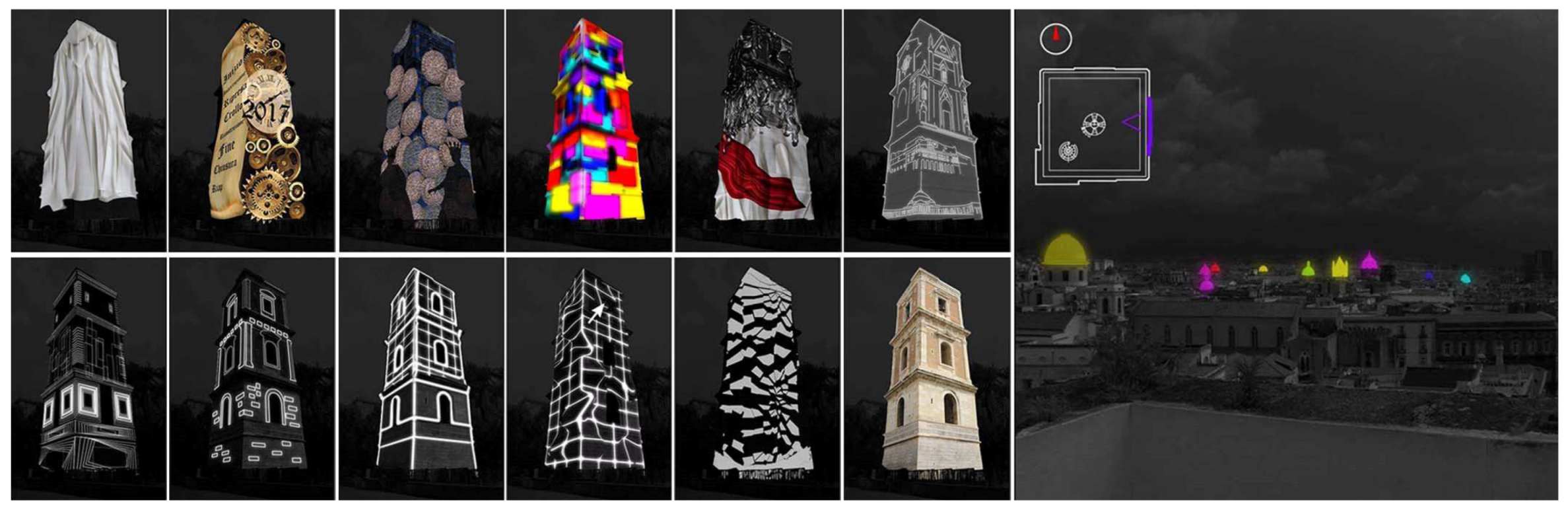

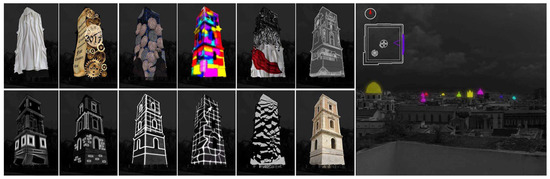

Il suono della luce is the title of a visual identity and video-mapping project for the urban regeneration of the monumental bell tower of the monastery of Santa Chiara. Built by Roberto d’Angiò in the first half of the 13th century, the bell tower has collapsed, been demolished and remodelled into its present configuration, in which: the marble basement and inscriptions in large Gothic letters date from the thirteenth century; while the next three floors are baroque. The bell tower is an important Neapolitan monument. The barycentric position in the historic centre and its remarkable height make it an extraordinarily panoramic point and an attractor with a significant symbolic value of historical memory. A physical architecture able to assert itself as a “magnetic place”, an image of sociality and collective identity [15]. Based on this, there is a currently project that has been proposed to a commission for public funding to refurbish the bell tower and make the roof terrace accessible, thus returning it to the city and using it for cultural tourism events. It was presented by a local association, organisations, institutions as well as private investors. The video-mapping and visual identity meta-project (under the scientific co-ordination of the author) is respectively the signature of the young designers Paola Ferrara and Valentina Mozzillo.

The video-mapping intervention critically resumes the themes of contemporary architecture as the media surface and the risk of a reduction in the physical identity of the building to the benefit of the increasingly ephemeral skin. This doubt, due to the “increasingly communicative and dynamic architectural surfaces in which the envelope, from the static boundary between the architecture and the environment, seems to become an interactive membrane responsible for the sole exchange of energy and information” [16] (p. IV) was assumed as the aim of the meta-project to make the bell tower (architecture), and not the video projection (technology), the protagonist of the event. Technology is therefore a medium through which the bell tower can renew its urban role for the community and city.

The video installation proposal includes three interventions: on the exterior facades; on the three inner floors; on the roof. Paola Ferrara developed an idea for the inaugural event that includes a mapped video projection on the bell tower surfaces, transforming them into screens with dynamic and changing images that, projected into 2D, are perceived as three-dimensional. Il suono della luce alludes to bright images emitted by the bell tower which, like a lighthouse, spreads light in place of the traditional bell chimes. The goal is to “illuminate” the bell tower, returning it to the city with its identity value through the projecting of distinct animated images on three themes: chi sono (the historical origins); come sono fatto (the architectural configuration); dove vivo (the urban relationships). There are further interactive video projections with distinct content for the three height levels on the walls and arches inside the bell tower to return it to the city as a virtual museum and/or exhibition facility for events and exhibitions. There are two possible solutions to access the roof terrace: by day, visitors can enjoy the extraordinary 360° view of the city and, by virtue of real-time use of virtual reality, extend it to those who for many reasons cannot go up to the roof terrace (access to the various levels is only possible through a spiral staircase from one of the cantons); at night, the bell tower turns into a lighthouse that emits beams of light to illuminate other nodal points of the city, for example the domes. This luminous network will be suitably designed to be captured by high observation points such as Castel Sant’Elmo, the Reggio di Capodimonte, the Astronomical Observatory, extending the identity event from the architectural to the urban scale (Figure 9).

Figure 9.

Santa Chiara bell tower, Il suono della luce (graphic design by Paola Ferrara).

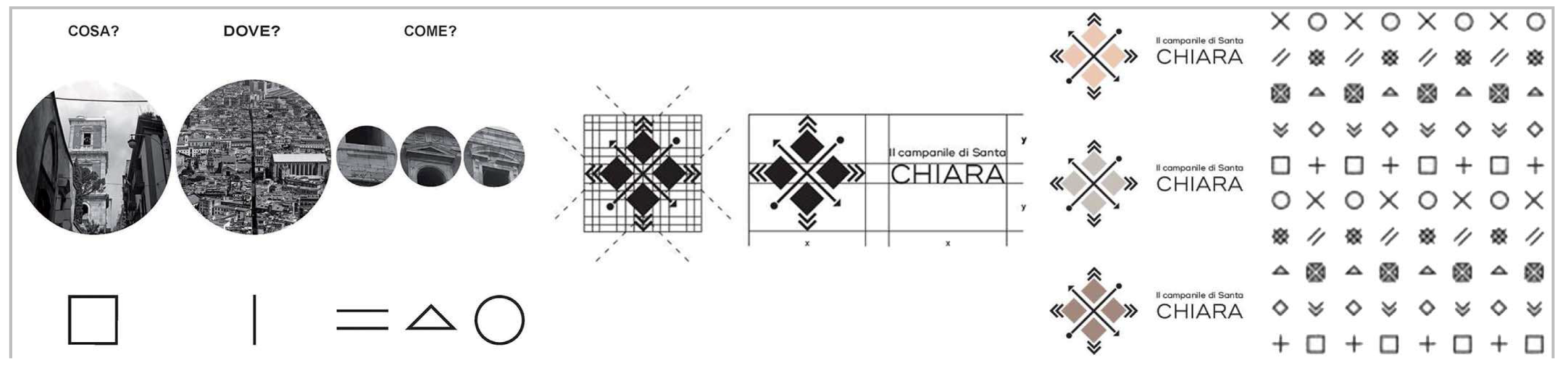

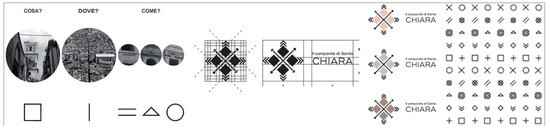

For the regeneration of the Santa Chiara bell tower, a visual identity system with the identification of an image that represents it as a cultural site was also considered. Inspired by contemporary city branding experiences, Valentina Mozzillo realised a visual identity system made up of symbols derived from existing or inspired forms of history, capable of existing independently or forming a pattern. The system originated from three connotative questions about the bell tower: what we are talking about? where is it? what is it like?. These questions are followed by the identification of minimal and modular graphic signs: a square for the shape of the bell tower; a vertical segment for Via Spaccanapoli, onto which the bell tower looks; two parallel segments, a triangle and a circle, for the architectural decorative elements.

The design of the brand comes from the conceptual sum of these signs. The lettering is Ridley Grotesk Demo and Arial, fonts without grace that recall the rectangular shapes of the bell tower. The colours used are pink, grey and taupe (obtained from the colours of the inscription) in addition to black and white. The graphic signs are composed to form a decorative pattern to be used as the background of illustrations. It consists of ten regularly horizontally and/or vertically repeated marks. Based on this system, various graphic products for events, institutional material, tourism and merchandising, as well as a short video that describes the geometric-configurational genesis of the brand and the compositional reasons were designed (Figure 10).

Figure 10.

Santa Chiara bell tower, visual identity system (graphic design by Valentina Mozzillo).

6. Conclusions

The examples presented draw attention to the critical role of the drawing as a visual image, “an extension of the mind, with the task of making” the mind “operational” [17] (p. 22). The visual image is a conatiner of meaning that is totally free from technological innovation, both in relation to the development of new expressive potentials, as well as for the conditioning and cultural implications it involves in relation to the relationship between reality and representation [18,19,20]. The digital dimension and new media have widely and variedly changed everyday life, society, culture, with constant challenges to habits, the use of the body and mental operations. Presi nella rete is the title of an interesting work by Raffaele Simone, where the author considers the risks of being constantly connected to a “media sphere”, which replaces material reality and whose developments and results produced in the mind are not yet fully clear [21]. Architecture is not alien to this new historical context as well as to the overwhelming development of new digital technologies. A series of recent artistic and design projects draw attention to: the building enevlope; the relationship between design, architectural culture and the digital world; the construction of the meaning of the visual image [22].

Street art and multimedia architectural installations are contemporary forms of expression that allow for the construction of visual images on an urban scale. The examples presented and described for Naples are testimony to the determined will to attribute meaning to images in relation to the different specificities of the physical and socio-cultural contexts of architecture and the environment. Murals and stencils are transforming city buildings and streets into communal assests, making peripheral and/or degraded neighbourhoods a multifaceted resource. This current phenomenon is generating a new image of urban landscape and, at the same time, opening up the debate on the opportunity to preserve these temporary images. These themes were discussed on 26 October 2016, at the University of Tuscia, during the study day entitled Arte sui muri della città. Street art e urban art: questioni aperte that, in addition to examining the functions and meanings of these symbolic images, drew attention to the possible musealisation of these open-air testimonies [23]. It is still unknown how this debate will develop. It could intersect with what has been going on for years on the ability of museum structures (traditionally conceived) to transfer culture to visitors. Information and communication technologies are playing a significant role on this issue, although they are not critical of the potential for their correct use. The concept of the museum has been significantly transformed: from a physical container to a new sensitive identity, capable of offering experiences of multisensory fruition. The digital dimension is renewing and increasing the way of knowledge and dissemination with a constant interaction between visitor and work of art, along with the simultaneous involvement of multiple dimensions (corporeal, emotional, cognitive, social). In this sense, the relationship between the museum and the works of art is changing since the museum itself is transforming into a work of art to be enjoyed. New ways of conceiving space and paths involve visitors in a continuous dialogue according to a temporary condition of works of art and displays as cultural policy increasingly focuses on exhibitions and temporary events [24,25,26].

The design proposals presented here are also based on these assumptions. In both cases, multimedia architectural displays have been designed based on the specific historical and social identity features of the site. The tangible and intangible spaces (involved and/or designed) take on the dimension of a museum, so to speak ‘ephemeral’, which communicates to visitors (residents and/or visitors) temporary events but with roots intimately linked to the environment and to the architecture. The specificity of the site, along with the socio-cultural goals are the real protagonists of the events, while multimedia digital images and technologies are modelled, like a costume, onto these tangible and inadmissible identities. Not surprisingly, the cultural portal of Scampia is proposed on the facades of the two buildings that look over the underground exit, a link between the the city and several surrounding provinces. Unintentionally, the digital video-mapping event projected onto the Santa Chiara bell tower concludes with the reproduction of its real image. The final aim is therefore common: to examine the look that makes the image symbolic and integrates it with the architecture and the city. For this purpose, inventive design is a “thinking code” predisposed to develop visual imagery [27] (pp. 76–80).

Acknowledgments

Ringrazio l’architetto Vincenzo Cirillo per la redazione del disegno (Figure 6b).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest

References

- Gombrich, E.H. L’immagine visiva come forma di comunicazione. In L’immagine e L’occhio, Altri Studi Sulla Psicologia Della Rappresentazione Pittorica; Giulio Einaudi Editore: Torino, Italy, 1985; pp. 155–185. ISBN 88-06-58073-6. [Google Scholar]

- Lorenz, K. Evoluzione e Modificazione del Comportamento; Universale Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, Italy, 1971; ISBN 978-88-339-0293-7. [Google Scholar]

- Arnheim, R. Arte e Percezione Visiva, 3nd ed.; Feltrinelli: Milano, Italy, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Zennaro, P. Architettura Senza. Micro Esegesi Della Riduzione Negli Edifici Contemporanei; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2009; ISBN 978-88-568-0614-4. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, W.J. La Città del Bits. Spazi, Luoghi e Autostrade Informatiche; Mondadori Electa: Milano, Italy, 1997; ISBN 978-88-435-6023-3. [Google Scholar]

- Galimberti, U. Psiche e Techne: L’uomo Nell’età Della Tecnica; Feltrinelli: Milano, Italy, 2002; ISBN 978-88-078-1704-5. [Google Scholar]

- Fekner, J.; Schacter, R. The World Atlas of Street Art and Graffiti; NewSouth Publishing: Sydney, Australia, 2013; ISBN 978-17-422-3377-2. [Google Scholar]

- Powers, S. A Love Letter to the City; Princeton Architectural Press: New York, NY, USA, 2014; ISBN 978-16-168-9208-1. [Google Scholar]

- Il San Gennaro Operaio di Jorit per Far Rinascere Forcella. Available online: http://napoli.repubblica.it/cronaca/2015/09/16/news/il_san_gennaro_operaio_di_jorit_per_far_rinascere_forcella-122978158/ (accessed on 15 August 2017).

- Il murale di San Gennaro a Forcella Somiglia a Nunzio Giuliano. Available online: http://corrieredelmezzogiorno.corriere.it/napoli/cronaca/15_settembre_14/murale-san-gennaro-forcella-somiglia-nunzio-giuliano-ma-operaio-quartiere-d7e61bf6-5aca-11e5-af54-c122b65fd5c8.shtml (accessed on 15 August 2017).

- Ciotta, E. Street Art: La Rivoluzione Nelle Strade; Bepress: Lecce, Italy, 2011; ISBN 978-88-9613-023-0. [Google Scholar]

- Napoli, Graffiti Perduti: Un Giorno Saranno Restaurati Come Gli Affreschi? Available online: http://corrieredelmezzogiorno.corriere.it/napoli/notizie/arte_e_cultura/2014/6-marzo-2014/da-banksy-zemi-pignon-graffiti-perduti-napoli-2224174188244.shtml (accessed on 1 August 2017).

- INSIDE OUT | Napoli: Il Rinascimento Parte da Qui. Available online: http://www.insideoutproject.net/en/group-actions/italy-naples (accessed on 31 August 2017).

- Biennale del Libro d’Artista. Available online: http://www.biennaledellibrodartista.org/ (accessed on 10 September 2017).

- Torres, M. Luoghi Magnetici. Spazi Pubblici Nella Città Moderna e Contemporanea; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2009; ISBN 978-88-464-1715-2. [Google Scholar]

- Gasparini, K. Design in Superficie: Tecnologie Dell’involucro Architettonico Mediatico; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2009; ISBN 978-88-568-0567-3. [Google Scholar]

- De Rubertis, R. Il Disegno DELL’ARCHITETTURA; La Nuova Italia Scientifica: Roma, Italy, 1994; ISBN 88-430-0272-4. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado, T. Reale e Virtuale; Feltrinelli: Milano, Italy, 1994; ISBN 978-88-070-8110-1. [Google Scholar]

- Negroponte, N. Essere Digitali; Sperling & Kupfer: Milano, Italy, 2004; ISBN 978-88-827-4724-4. [Google Scholar]

- Zerlenga, O. Dalla Grafica All’infografica: Nuove Frontiere Della Rappresentazione nel Progetto di Prodotto e di Comunicazione; Claudio Grenzi Editore: Foggia, Italy, 2007; ISBN 978-88-8431-247-1. [Google Scholar]

- Simone, R. Presi Nella Rete: La mente ai Tempi del Web; Garzanti: Milano, Italy, 2012; ISBN 978-88-116-0108-1. [Google Scholar]

- Sacchi, L.; Unali, M. Architettura e Cultura Digitale; Skira: Milano, Italy, 2003; ISBN 978-88-849-1408-8. [Google Scholar]

- Mania, P.; Petrilli, R.; Cristallini, E. Arte Sui Muri Della Città. Street art e Urban Art: Questioni Aperte; Round Robin: Roma, Italy, 2017; ISBN 978-88-987-1585-5. [Google Scholar]

- Antinucci, F. Comunicare Nel Museo; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 2014; ISBN 978-88-581-1468-1. [Google Scholar]

- Martini, B. Il Museo Sensibile: Le Tecnologie ICT al Servizio Della Trasmissione Della Conoscenza; Franco Angeli: Milano, Italy, 2016; ISBN 978-88-917-2676-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pezzini, I. Semiotica Dei Nuovi Musei; Laterza: Roma-Bari, Italy, 2011; ISBN 978-88-420-9545-3. [Google Scholar]

- Cervellini, F. Il Disegno Come Luogo del Progetto; Aracne: Roma, Italy, 2016; ISBN 978-88-548-9460-0. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).