Images for Deconstructing the Complexity and Images for Constructing the Collective Imagination in the Case of the Alpine Landscape. A Selected Overview †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

- the circular panoramas of mountain peaks, based on vertical projections—starting from the very first drawn by Hans Konrad Escher von der Linth in 1792 [11,12]—with the toponymic detection of the peaks, now resumed by applications of Augmented Reality for Mountain Peak Detection in images from mobile devices [13];

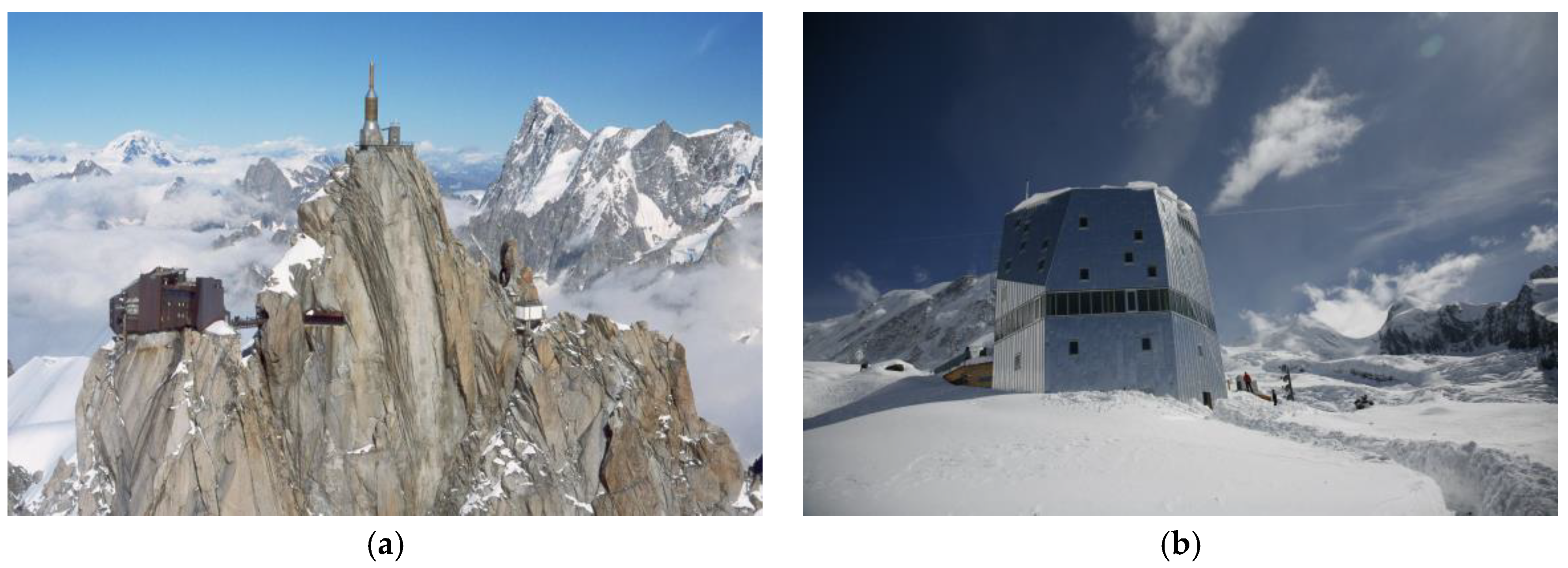

- the images of romantic taste, that, according to the aesthetic category of sublime, are characterized by the artificial accentuation of dizzying features such as height, slopes, depths, born in the romantic period but still frequently used in cinematography and video games with the creation of fantastic digital settings;

- the picturesque images of alpine buildings and villages, based on the complementary contrast procedure between natural and artificial characters [2], procedure that is commonly used also nowadays in the creation of advertising pictures for the promotion of mountain resorts.

- These modes were extensively used even in the XX century, even in hybrid forms, such the production of deformed panoramic views for the promotion of ski resorts [14].

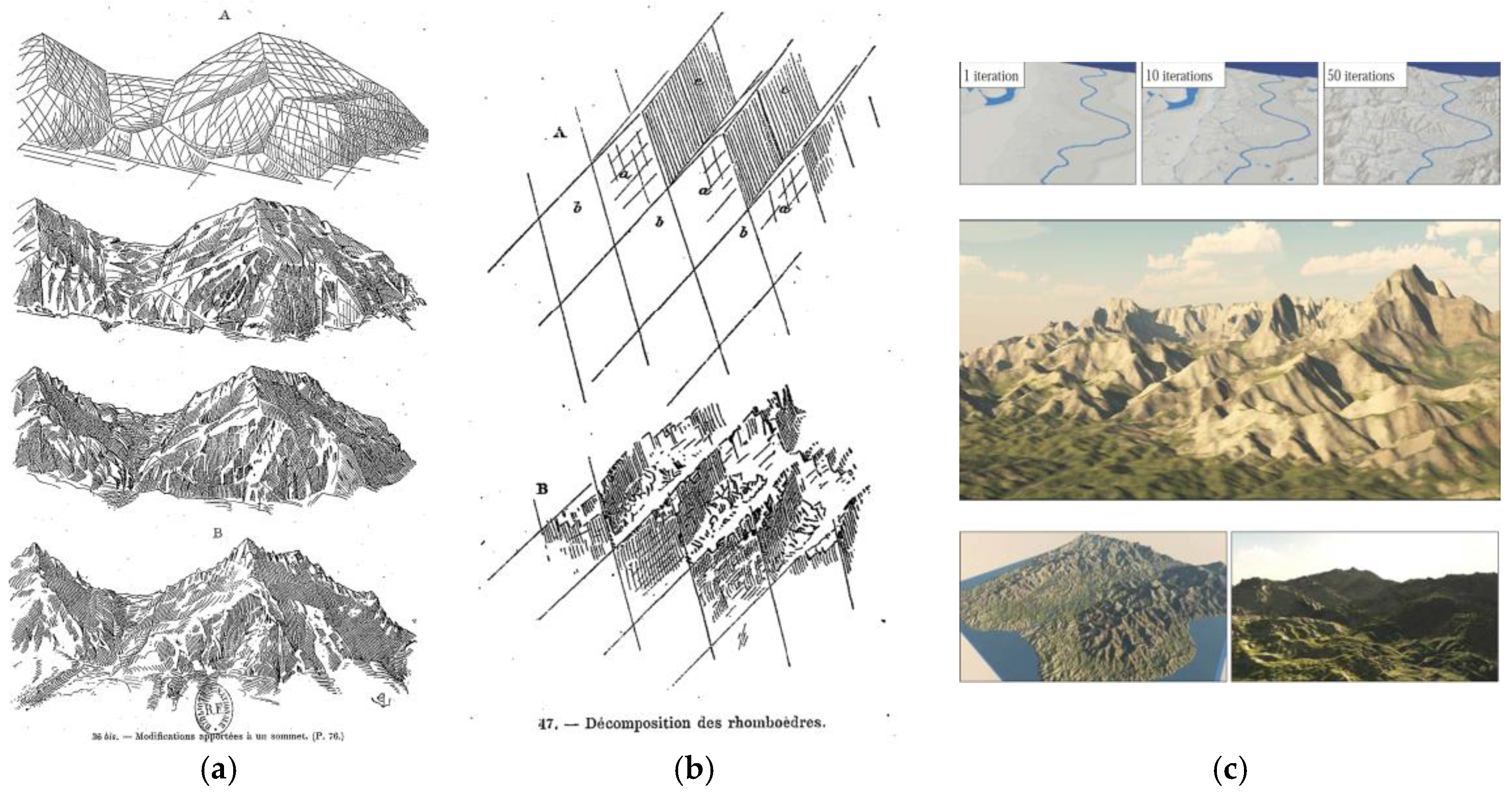

2. Deconstruction and Representation of Alpine Orography

2.1. Alpine Cartography

- XVI century—phase of representation of the main passes: the mountains are of no interest, and they are not represented in the maps; the maps individuate only the main Alpine passes and only occasionally the roads;

- XVII century—phase of detection of roads and the main mountains: as a general rule the main mountains are named, but the depiction is only symbolic.

- XVIII century—phase of the survey of the territory: the first triangulated surveys are limited to the planes and the most accessible hills, while some regional mapping campaigns generated small scale mountain maps, mainly for military purposes. Although the graphics of these abstract landscape representations seemed rather clumsy, the accuracy of the geometric positions of topographic objects was nevertheless in the range of decameters to kilometers [15];

- XIX century—phase of the systematic recognition of the Alps: the first triangulated survey of the Alps dates from 1821. The triangulation using new theodolites allowed to survey and map average-sized European countries at medium scales without major distortions and was the base for some great national mapping projects. In this context the entire Swiss Alps were measured and drawn in the Swiss National map—also known as “Dufour map”—at the scale of 1:100,000; that map set the standard in terms of representation of mountainous features for more than 100 years (was only replaced in the 1960s). At the end of the century remains few zones to be surveyed (that will be completely represented with the advent of aerial photogrammetry at the beginning of the XX century);

- first half of XX century—phase of systematic topographic mapping at bigger scale: in the first half of the 20th century, among new and more precise geodetic instruments and methods, the systematic recording and compilation of terrestrial and aerial images was a revolutionary improvement for updating topographic mountain maps. Changes of the man-made infrastructure or glacier movements could be detected easily, and represented in more precise maps (the European countries of the Alpine region have uniform map series with complementary scales, e.g., 1:100,000, 1:50,000 and 1:25,000).

- end of XX century, until now—phase of digital mountain cartography: In the second half of the 20th century, mountain cartography was fundamentally influenced by two other developments: the success of computerization and the broad availability of remote sensing images. This new, digital infrastructure supports a broad scope of new cartographic representations. Improved computer technologies and changed habits of map users now lead towards the integration of multimedia technologies and interactivity in order to provide theme-specific and user-centred presentations. With web-interface 3D terrain models, such as Google Earth or the interactive Atlas of Switzerland, the user can choose the preferred data layers and will add own topographic or textual layers. The desired section of the landscape, the view settings, and finally the output format can be deliberately chosen. Using such tools, the map user creates his own personalised representations, which can, e.g., be individually used for mountain hikes or as a planning instrument.

2.2. Panoramic Views

3. Construction of the Collective Imagination of the Alps

Deformation and Perception. Sublime Images

4. A Conclusion: Imaginative and Physical Construction of the Alpine Environment

- vastness: in the second half on 20th century there was a process of progressive and aggressive enlargement of the main ski resorts [3]; the panoramic images tend to highlight the sense of vastness of the resort deforming the terrain in order to improve the dimensions of the lift-accessed areas in comparison to natural terrain (Figure 5);

- beauty: the panoramic images tend to improve the impression of height and verticality of the most prominent surrounding peaks, deform the terrain in order to depict the most notable natural features (lakes, landmarks, ski-line) and depict an exaggerate snow cover;

- dreams: the marketing promote the stereotyped image of a resort with consistent snow coverage and no obstacles; this is a stereotype that have some consequences in the reality: excavation and transportation of big masses of soil to remove natural obstacles, creation of artificial water reservoirs and plants for the production of artificial snow, etc.

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Garimoldi, G. L’immagine contesa. L’iconografia alpina fra belle arti e fotografia. In Le Cattedrali Della Terra. La Rappresentazione Delle Alpi in Italia e in Europa 1848–1918, 1st ed.; Scherini, L., Ed.; Electa: Milano, Italy, 2000; pp. 118–124. [Google Scholar]

- De Rossi, A. La costruzione delle Alpi. Immagini e Scenari del Pittoresco Alpino (1773–1914), 1st ed.; Donzelli: Rome, Italy, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- De Rossi, A. La costruzione delle Alpi. Il Novecento e il Modernismo Alpino (1917–2017), 1st ed.; Donzelli: Rome, Italy, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Aliprandi, L.; Aliprandi, G. Le Grandi Alpi nella Cartografia 1482–1885. Volume I. Storia della Cartografia Alpina; Priuli & Verlucca: Ivrea, Italy, 2005; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Audisio, A. (Ed.) Immagini e Immaginario Della Montagna. 1740–1840; Museo Nazionale della Montagna: Torino, Italy, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, H.A. The Sciences of the Artificial, 3rd ed.; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Viollet-le-Duc, E.-E. Le Massif du Mont-Blanc, Etude sur sa Constitution Geodesique et Géologique, sur ses Transformations et sur l’état Ancien et Moderne de ses Glaciers; J. Baudry: Paris, France, 1876. [Google Scholar]

- Smelik, R.; de Kraker, K.; Groenewegen, S.; Tutenel, T.; Bidarra, R. A Survey of procedural methods for terrain modelling. In Proceedings of the CASA Workshop on 3D Advanced Media in Gaming and Simulation (3AMIGAS), Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 16 June 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cordonnier, G.; Braun, J.; Cani, M.P.; Benes, B.; Galin, É.; Peytavie, A.; Guérin, É. Large Scale Terrain Generation from Tectonic Uplift and Fluvial Erosion. Comput. Graph. Forum 2016, 35, 165–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batzing, W. Le Alpi. Una Regione Unica al Centro Dell’europa; Bollati Boringhieri: Torino, Italy, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Bordini, S. Storia del Panorama. La Visione Totale Nella Pittura del XIX Secolo; Officina Edizioni: Roma, Italy, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Brandenberger, R.; Smith, H.A.; Solar, G. Die ersten Panoramen der Alpen. Zeichnungen, Ansichten, Panoramen und Karten. The First Panoramas of the Alps. Drawings, Views, Panoramas and Maps. Hans Conrad Escher von·der Linth; Brandenberger, R., Ed.; Baeschlin: Glarus, Switzerland, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Fedorov, R.; Frajberg, D.; Fraternali, P. A Framework for Outdoor Mobile Augmented Reality and Its Application to Mountain Peak Detection. In Augmented Reality, Virtual Reality, and Computer Graphics. AVR 2016. Lecture Notes in Computer Science; De Paolis, L., Mongelli, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Basel, Switzerland, 2016; Volume 9768, pp. 281–301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tait, A. Mountain Ski Maps of North America: A Preliminary Survey and Analysis of Style. Cartogr. Perspect. 2010, 67, 5–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haberling, C.; Hurni, L. Mountain cartography: Revival of a classic domain. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2002, 57, 134–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maps of Switzerland, Swiss Confederation. Available online: https://map.geo.admin.ch (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- De Saussure, H.B. Voyages dans les Alpes, Précédés d’un Essai sur L’histoire Naturelle des Environs de Genève; Samuel Fauche: Neuchatel, Switzerland, 1779; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Anker, V. Dal viandante romantico alla folla dei panorami: Frontiere e ibridazioni nella rappresentazione dello spazio alpestre. In Le Cattedrali della Terra. La Rappresentazione delle Alpi in Italia e in Europa 1848–1918; 1st ed.; Scherini, L., Ed.; Electa: Milano, Italy, 2000; pp. 26–30. [Google Scholar]

- PeakFinder. Available online: https://www.peakfinder.org (accessed on 18 September 2017).

- Atlas of Switzerland. Available online: http://www.atlasderschweiz.ch (accessed on 18 September 2017).

- Franco, C.; Maumi, C. The construction of a territory in the Alps. Infrastructure for mass tourism. Techne—J. Technol. Archit. Environ. 2016, 172–179. Available online: http://www.fupress.net/index.php/techne/article/view/18418/17124 (accessed on 20 September 2017). [CrossRef]

- Burke, E. A Philosophical Inquiry into the Origin of our Ideas of the Sublime and the Beautiful; R. and J. Dodsley: London, UK, 1756. [Google Scholar]

- Ginsborg, H. Kant’s Aesthetics and Teleology. In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy; Fall 2014 Edition; Zalta, E.N., Ed.; Available online: https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2014/entries/kant-aesthetics/ (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- Nicolson, M.H. Mountain Gloom and Mountain Glory. The Development of the Aesthetic of the Infinite; W. W Norton: New York, NY, USA, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Hauptman, W. La Suisse Sublime vue par !es Peintres Voyageurs. 1770–1914; Electa: Milano, Italy, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Scaramellini, G. Il «pittoresco» e il «sublime» nella natura e nel paesaggio. Scrittura e iconografia nel viaggio romantico nelle Alpi. In Geofilosofia; Baldino, M., Bonesio, L., Resta, C., Eds.; Lyasis: Sondrio, Italy, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, C. The Landscapes of the Sublime 1700–1830. Classic Ground; Palgrave Macmillan: Basingstoke, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Tremblet, A. The Mountain Sublime of Philip James de Loutherbourg and Joseph Mallord William Turner, Journal of Alpine Research | Revue de géographie alpine (Online), 2016, 104-2, Online since 24 September 2016, connection on 12 December 2016. Available online: http://rga.revues.org/3395 (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- Le Cattedrali della Terra. La Rappresentazione delle Alpi in Italia e in Europa 1848–1918, 1st ed.; Scherini, L. (Ed.) Electa: Milano, Italy, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Compton, E.T. Der Cimon della Pala in den Dolomiten, 1896, via Wikimedia Commons. Available online: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File%3AEdward_Theodore_Compton_Der_Cimon_della_Pala_in_den_Dolomiten_1896.jpg (accessed on 20 September 2017).

- Bratkova, M.; Shirley, P.; Thompson, W.B. Artistic rendering of mountainous terrain. ACM Trans. Graph. 2009, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balzarini, R.; Dalmasso, A.; Murat, M. A study on mental representations for realistic visualization. The particular case of ski trail mapping. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2015, 40, 495–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, T. A View from on High: Heinrich Berann’s Panoramas and Landscape Visualization Techniques for the U.S. National Park Service. Cartogr. Perspect. 2000, 38–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skimaps. Available online: https://skimap.org/ (accessed on 18 September 2017).

- Deng, H.; Zhang, L.; Ma, J.; Kang, Z. Interactive panoramic map-like views for 3D mountain navigation. Comput. Geosci. 2011, 37, 1816–1824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenny, H.; Jenny, B.; Cartwright, W.E.; Hurni, L. Interactive Local Terrain Deformation Inspired by Hand-painted Panoramas. Cartogr. J. 2011, 48, 11–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2017 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Piumatti, P. Images for Deconstructing the Complexity and Images for Constructing the Collective Imagination in the Case of the Alpine Landscape. A Selected Overview. Proceedings 2017, 1, 957. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090957

Piumatti P. Images for Deconstructing the Complexity and Images for Constructing the Collective Imagination in the Case of the Alpine Landscape. A Selected Overview. Proceedings. 2017; 1(9):957. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090957

Chicago/Turabian StylePiumatti, Paolo. 2017. "Images for Deconstructing the Complexity and Images for Constructing the Collective Imagination in the Case of the Alpine Landscape. A Selected Overview" Proceedings 1, no. 9: 957. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090957

APA StylePiumatti, P. (2017). Images for Deconstructing the Complexity and Images for Constructing the Collective Imagination in the Case of the Alpine Landscape. A Selected Overview. Proceedings, 1(9), 957. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings1090957