Predicting Health Care Costs Using Evidence Regression †

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Related Work

2.1. Health Care Cost Prediction

2.2. Interpretability

2.3. Dempster Shafer Theory

3. Data and Problem Description

- Demographics: Patient gender and age.

- Patients attributes: General information about patients such as height, weight, body fat, and waist measurement.

- Health checks: Results from health check exams a patient had undergone. Japanese workers undergo these exams annually by law. A code indexes each exam, and the result is also included. Some examples are creatinine levels and blood pressure. There are 28 different types of exams, and the date when they were collected is also included.

- Diagnosis: Diagnosis for a patient illness registered by date and identified by their ICD-10 codes [43].

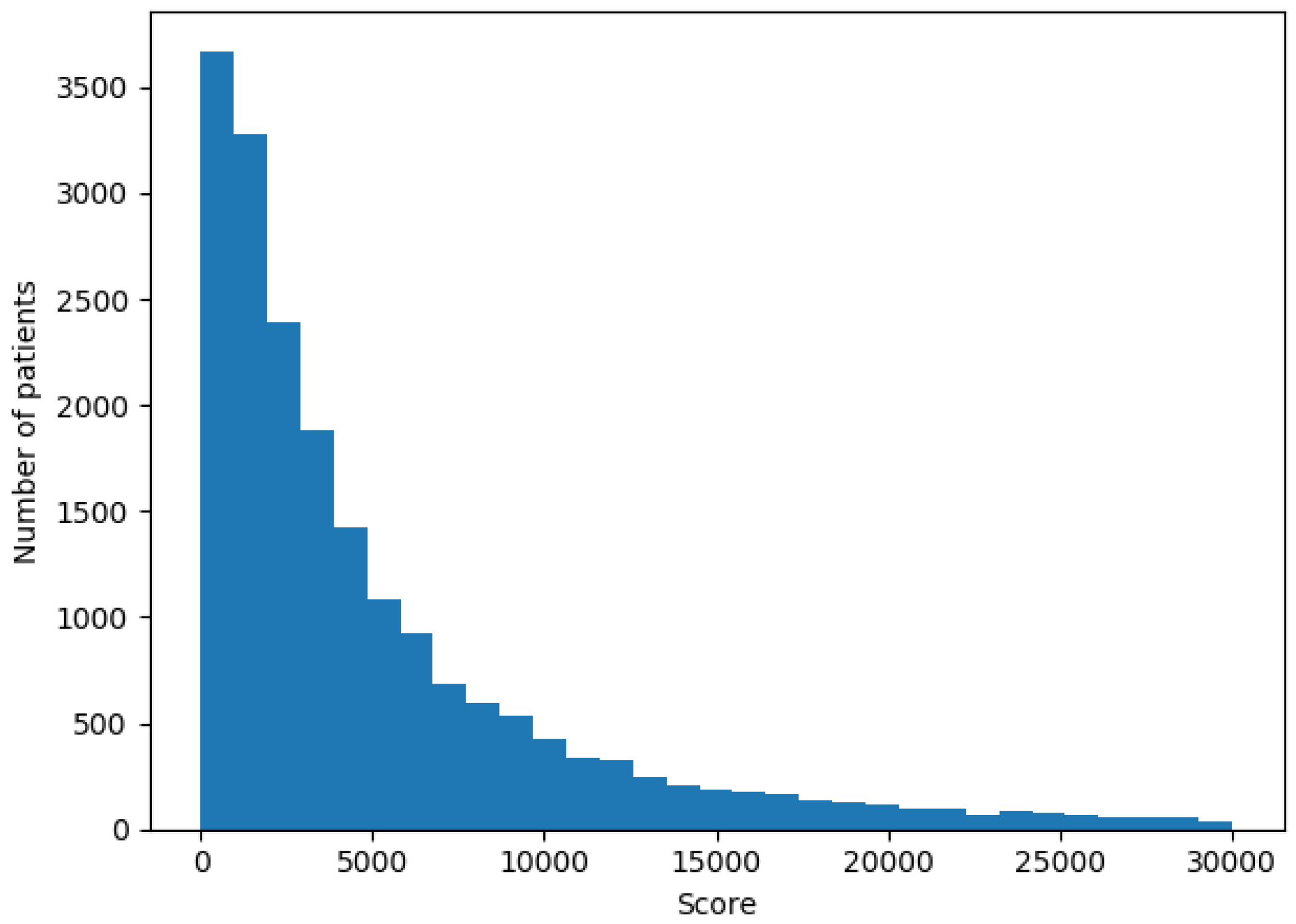

- Billing information: Each patient had a score registered for each visit or stay in the hospital. This score translates directly to the cost of a patient bill and this is the value we wanted to predict for the next year.

4. Proposed Model

4.1. Model Implementation

4.2. Training Phase

4.3. Computing Time Optimization

4.4. Interpretability

5. Experiments and Results

6. Discussion and Conclusions

References

- World Health Organization. Public Spending on Health: A Closer Look at Global Trends; Technical report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018.

- Yoo, I.; Alafaireet, P.; Marinov, M.; Pena-Hernandez, K.; Gopidi, R.; Chang, J.F.; Hua, L. Data mining in healthcare and biomedicine: A survey of the literature. J. Med. Syst. 2012, 36, 2431–2448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilger, M.; Manning, W.G. Measuring overfitting in nonlinear models: A new method and an application to health expenditures. Health Econ. 2015, 24, 75–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diehr, P.; Yanez, D.; Ash, A.; Hornbrook, M.; Lin, D. Methods for analyzing health care utilization and costs. Ann. Rev. Public Health 1999, 20, 125–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kronick, R.; Gilmer, T.; Dreyfus, T.; Ganiats, T. CDPS-Medicare: The Chronic Illness and Disability Payment System Modified to Predict Expenditures for Medicare Beneficiaries; Final Report to CMS. 2002. Available online: http://www.hpm.umn.edu/ambul_db/db/pdflibrary/dbfile_91049.pdf (accessed on 24 June 2002).

- Morid, M.A.; Kawamoto, K.; Ault, T.; Dorius, J.; Abdelrahman, S. Supervised Learning Methods for Predicting Healthcare Costs: Systematic Literature Review and Empirical Evaluation. AMIA Ann. Symp. Proc. 2017, 2017, 1312. [Google Scholar]

- Petit-Renaud, S.; Denœux, T. Nonparametric regression analysis of uncertain and imprecise data using belief functions. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2004, 35, 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, A.M. Models for Health Care; University of York, Centre for Health Economics: York, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Mihaylova, B.; Briggs, A.; O’Hagan, A.; Thompson, S.G. Review of statistical methods for analysing healthcare resources and costs. Health Econ. 2011, 20, 897–916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blough, D.K.; Madden, C.W.; Hornbrook, M.C. Modeling risk using generalized linear models. J. Health Econ. 1999, 18, 153–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leung, S.F.; Yu, S. On the choice between sample selection and two-part models. J. Econometr. 1996, 72, 197–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marshall, A.H.; Shaw, B.; McClean, S.I. Estimating the costs for a group of geriatric patients using the Coxian phase-type distribution. Stat. Med. 2007, 26, 2716–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.M.; Kang, J.O.; Suh, Y.M. Comparison of hospital charge prediction models for colorectal cancer patients: neural network vs. decision tree models. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2004, 19, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsimas, D.; Bjarnadóttir, M.V.; Kane, M.A.; Kryder, J.C.; Pandey, R.; Vempala, S.; Wang, G. Algorithmic prediction of health-care costs. Oper. Res. 2008, 56, 1382–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frees, E.W.; Jin, X.; Lin, X. Actuarial applications of multivariate two-part regression models. Ann. Actuar. Sci. 2013, 7, 258–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sushmita, S.; Newman, S.; Marquardt, J.; Ram, P.; Prasad, V.; Cock, M.D.; Teredesai, A. Population cost prediction on public healthcare datasets. In Proceedings of the 5th International Conference on Digital Health 2015, Florence, Italy, 18–20 May 2015; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 87–94. [Google Scholar]

- Duncan, I.; Loginov, M.; Ludkovski, M. Testing alternative regression frameworks for predictive modeling of health care costs. N. Am. Actuar. J. 2016, 20, 65–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elith, J.; Leathwick, J.R.; Hastie, T. A working guide to boosted regression trees. J. Anim. Ecol. 2008, 77, 802–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sutton, C.D. Classification and regression trees, bagging, and boosting. Handb. Stat. 2005, 24, 303–329. [Google Scholar]

- Zurada, J.M. Introduction to Artificial Neural Systems; West Publishing Company: St. Paul, MN, USA, 1992; Volume 8. [Google Scholar]

- Breiman, L. Classification and Regression Trees; Routledge: London, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, Z.C. The mythos of model interpretability. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.03490. [Google Scholar]

- Caruana, R.; Lou, Y.; Gehrke, J.; Koch, P.; Sturm, M.; Elhadad, N. Intelligible models for healthcare: Predicting pneumonia risk and hospital 30-day readmission. In Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Sydney, Australia, 10–15 August 2015; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1721–1730. [Google Scholar]

- Ustun, B.; Rudin, C. Supersparse linear integer models for optimized medical scoring systems. Mach. Learn. 2016, 102, 349–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattekari, S.A.; Parveen, A. Prediction system for heart disease using Naïve Bayes. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Math. Sci. 2012, 3, 290–294. [Google Scholar]

- Montbriand, M.J. Decision tree model describing alternate health care choices made by oncology patients. Cancer Nurs. 1995, 18, 104–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fonarow, G.C.; Adams, K.F.; Abraham, W.T.; Yancy, C.W.; Boscardin, W.J.; ADHERE Scientific Advisory Committee, Study Group, and Investigators. Risk stratification for in-hospital mortality in acutely decompensated heart failure: Classification and regression tree analysis. Jama 2005, 293, 572–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maseleno, A.; Hasan, M.M. Skin diseases expert system using Dempster-Shafer theory. Int. J. Int. Syst. Appl. 2012, 4, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Peñafiel, S.; Baloian, N.; Pino, J.A.; Quinteros, J.; Riquelme, Á.; Sanson, H.; Teoh, D. Associating risks of getting strokes with data from health checkup records using Dempster-Shafer Theory. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 20th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT), Gang’weondo, Korea, 11–14 February 2018; pp. 239–246. [Google Scholar]

- Shrikumar, A.; Greenside, P.; Kundaje, A. Learning important features through propagating activation differences. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1704.02685. [Google Scholar]

- Zeiler, M.D.; Fergus, R. Visualizing and understanding convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Zurich, Switzerland, 6–12 September 2014; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; pp. 818–833. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Model-agnostic interpretability of machine learning. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.05386. [Google Scholar]

- Craven, M.; Shavlik, J.W. Extracting tree-structured representations of trained networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Denver, CO, USA, 27 November–2 December 1996; pp. 24–30. [Google Scholar]

- Baehrens, D.; Schroeter, T.; Harmeling, S.; Kawanabe, M.; Hansen, K.; MÞller, K.R. How to explain individual classification decisions. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2010, 11, 1803–1831. [Google Scholar]

- Kononenko, I. An efficient explanation of individual classifications using game theory. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2010, 11, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Krause, J.; Perer, A.; Ng, K. Interacting with predictions: Visual inspection of black-box machine learning models. In Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, CA, USA, 7–12 May 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 5686–5697. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, J.; Troyanskaya, O.G. Predicting effects of noncoding variants with deep learning–based sequence model. Nat. Methods 2015, 12, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Why should i trust you?: Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mmining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 1135–1144. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer, G. A Mathematical Theory of Evidence; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1976; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Shafer, G. Dempster’s rule of combination. Int. J. Approx. Reason. 2016, 79, 26–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niu, G.; Yang, B.S. Dempster–Shafer regression for multi-step-ahead time-series prediction towards data-driven machinery prognosis. Mechan. Syst. Signal Process. 2009, 23, 740–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraldi, P.; Di Maio, F.; Al-Dahidi, S.; Zio, E.; Mangili, F. Prediction of industrial equipment remaining useful life by fuzzy similarity and belief function theory. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 83, 226–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Hhealth: ICF; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2001.

- Denoeux, T. A k-nearest neighbor classification rule based on Dempster-Shafer theory. IEEE Trans. Syst. Man Cybern. 1995, 25, 804–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smets, P. What is Dempster-Shafer’s model. In Advances in the Dempster-Shafer Theory of Evidence; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1994; pp. 5–34. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, J.; Douze, M.; Jégou, H. Billion-scale similarity search with GPUs. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lantz, B. Machine Learning with R; Packt Publishing Ltd.: Birmingham, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

| Statistics | Value |

|---|---|

| Total number of patients | 25,464 |

| Mean score for costs | 10,649 |

| Mean age | 47.09 |

| % Male | 48.59 |

| % Female | 51.41 |

| Variable Number | Description |

|---|---|

| 1–2 | Demographics |

| 3–30 | Health checkup results |

| 31–51 | ICD-10 Diagnosis groups |

| 52 | Previous score |

| 53 | Actual score |

| Age | Gender | BMI | Children | Smoker | True Score | Predicted Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 41 | Male | 32.2 | 2 | No | 6836 | 7555 |

| Rule | Weight |

|---|---|

| 31.7640 < BMI < 32.9670 | 0.48 |

| gender = 0.0 | 0.48 |

| smoker = 0.0 | 0.48 |

| children = 2.0 | 0.48 |

| 40.3107 < age < 41.3560 | 0.22 |

| Model | MAE | MAPE | |

|---|---|---|---|

| IEVREG | 7638 | 0.77 | 0.44 |

| GB | 7966 | 0.80 | 0.40 |

| ANN | 8023 | 0.81 | 0.35 |

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Panay, B.; Baloian, N.; Pino, J.A.; Peñafiel, S.; Sanson, H.; Bersano, N. Predicting Health Care Costs Using Evidence Regression. Proceedings 2019, 31, 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2019031074

Panay B, Baloian N, Pino JA, Peñafiel S, Sanson H, Bersano N. Predicting Health Care Costs Using Evidence Regression. Proceedings. 2019; 31(1):74. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2019031074

Chicago/Turabian StylePanay, Belisario, Nelson Baloian, José A. Pino, Sergio Peñafiel, Horacio Sanson, and Nicolas Bersano. 2019. "Predicting Health Care Costs Using Evidence Regression" Proceedings 31, no. 1: 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2019031074

APA StylePanay, B., Baloian, N., Pino, J. A., Peñafiel, S., Sanson, H., & Bersano, N. (2019). Predicting Health Care Costs Using Evidence Regression. Proceedings, 31(1), 74. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2019031074