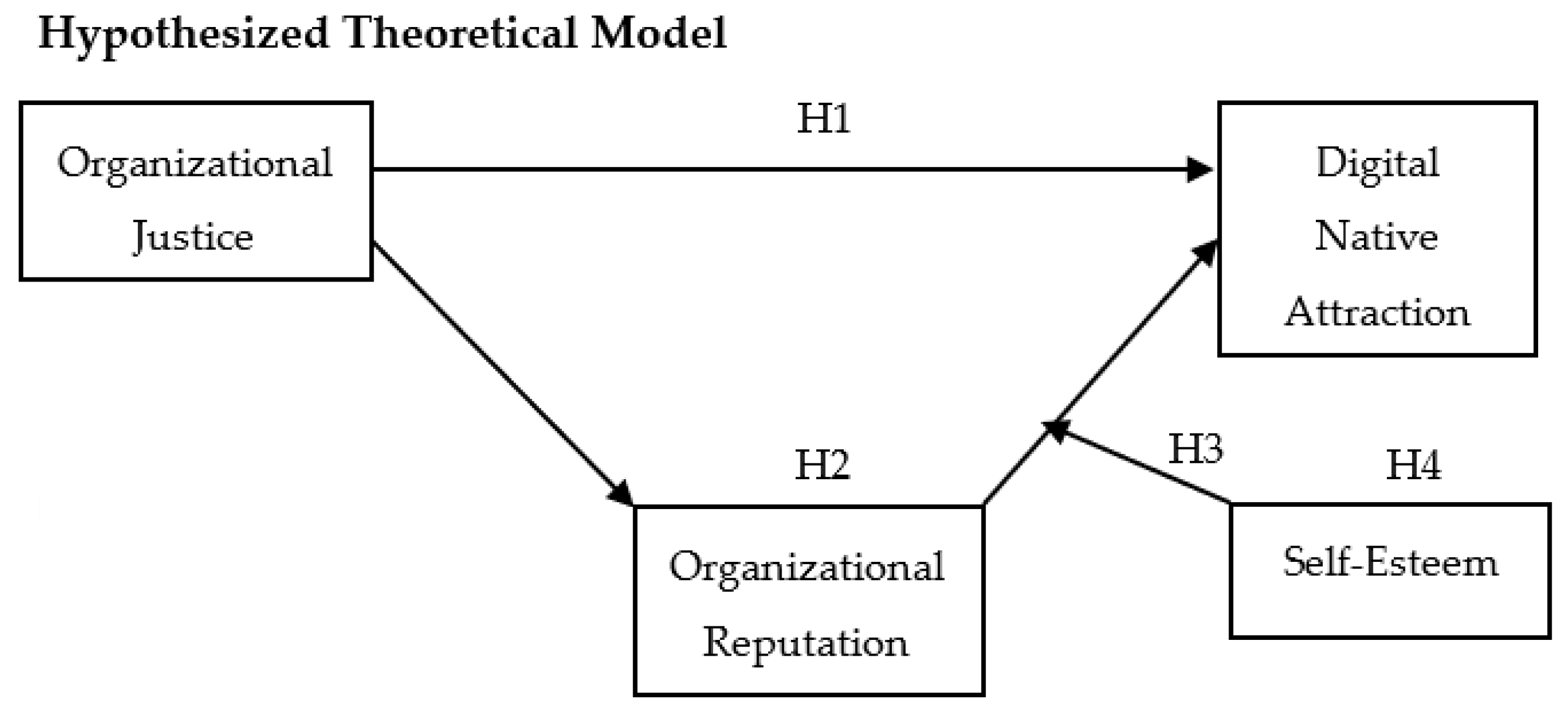

The Organizational Justice and Organizational Reputation Attracting Digital Natives with High Self-Esteem †

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

2.1. Digital Natives Attraction Related to Organizational Justice

2.2. The Role of Organizational Reputation in Attaracting Digital Native

2.3. Self-Esteem and Digital Native Attraction

3. Methodology

3.1. Design and Procedure

3.2. Measures

4. Data Analysis and Result

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Colbert, A.; Yee, N.; George, G. The digital workforce and the workplace of the future. Acad. Manag. J. 2016, 59, 731–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mesquita, A.; Oliveira, L.; Sequeira, A. The Future of the Digital Workforce: Current and Future Challenges for Executive and Administrative Assistants. In World Conference on Information Systems and Technologies; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Lipscomb, S.T.; Chandler, K.D.; Abshire, C.; Jaramillo, J.; Kothari, B. Early childhood teachers’ self-efficacy and professional support predict work engagement. Early Child. Educ. J. 2022, 50, 675–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prensky, M. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants Part 2: Do They Really Think Differently? Horizon 2001, 9, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoghbi-Manrique-de-Lara, P.; Aguiar-Quintana, T.; Suárez-Acosta, M.A. A justice framework for understanding how guests react to hotel employee (mis)treatment. Tour. Manag. 2013, 36, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulik, C.T.; Pepper, M.B.; Shapiro, D.L.; Cregan, C. The electronic water cooler: Insiders and outsiders talk about organizational justice on the internet. Communic. Res. 2012, 39, 565–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beersma, B.; Van Kleef, G.A. Why people gossip: An empirical analysis of social motives, antecedents, and consequences. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 2640–2670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mynewshub. Factors Undergraduate Choose Employment; Mynewshub: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Graham, M.E.; Cable, D.M. Consideration of the incomplete block design for policy-capturing research. Organ. Res. Methods 2001, 4, 26–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Cable, D.M. Firm reputation and applicant pool characteristics. J. Organ. Behav. 2003, 24, 733–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D.M.; Turban, D.B. The value of organizational reputation in the recruitment context: A brand-equity perspective. J. Appl. Soc. Psycol. 2003, 33, 2244–2266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cable, D.M.; Turban, D.B. Establishing the dimensions, sources and value of job seekers’ employer knowledge during recruitment. In Research in Personnel and Human Resources Management; Emerald Group Publishing Limited: Bingley, UK, 2001; Volume 20, pp. 115–163. [Google Scholar]

- Turban, D.B.; Keon, T.L. Organizational attractiveness—An interactionist perspective. J. Appl. Psychol. 1993, 78, 184–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lievens, F.; Slaughter, J.E. Employer image and employer branding: What we know and what we need to know. Annu. Rev. Organ. Psychol. Organ. Behav. 2016, 3, 407–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Chapman, D.S.; Uggerslev, K.L.; Carroll, S.A.; Piasentin, K.A.; Jones, D.A. Applicant attraction to organizations and job choice: A meta-analytic review of the correlates of recruiting outcomes. J. Appl. Psychol. 2005, 90, 928–944. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhart, K.H.; Ziegert, J.C. Why are individuals attracted to organizations? J. Manag. 2005, 31, 901–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rau, B.L.; Hyland, M.A.M. Role conflict and flexible work arrangements: The effects on appll6icant attraction. Pers. Psychol. 2002, 55, 111–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Highhouse, S.; Lievens, F.; Sinar, E.F. Measuring attraction to organizations. Educ. Psychol. Meas. 2003, 63, 986–1001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiman-smith, L.; Bauer, T.N.; Cable, D.M. Are you attracted? Do you intend to pursue? A recruiting policy-capturing study. J. Bus. Psychol. 2001, 16, 219–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ong, L. Employer branding and its influence on potential job applicants. Aust. J. Basic Appl. Sci. 2011, 5, 1088–1092. [Google Scholar]

- Uggerslev, K.L.; Fassina, N.E.; Kraichy, D. Recruiting through the stages: A meta-analytic test of predictors of applicant attraction at different stages of the recruiting process. Pers. Psychol. 2012, 65, 597–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crawshaw, J.R.; Cropanzano, R.; Bell, C.M.; Nadisic, T. Organizational justice: New insights from behavioural ethics. Hum. Relat. 2013, 66, 885–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skarlicki, D.P.; O’Reilly, J.; Kulik, C.T. Third-party reactions to employee (mis)treatment: A justice perspective. In The Oxford Handbook of Justice in the Workplace, 1st ed.; Cropanzano, R.S., Ambrose, M.L., Eds.; Elsevier Ltd.: London, UK, 2015; Volume 26, pp. 183–229. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Gowan, M.A. Corporate social responsibility, applicants’ individual traits, and organizational attraction: A person-organization fit perspective. J. Bus. Psychol. 2012, 27, 345–362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, C.A.; Karl, K.A.; Brey, E.T. Role of workplace romance policies and procedures on job pursuit intentions. J. Manag. Psychol. 2012, 27, 237–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, R.J.; Payne, S.C.; Taylor, A.B. Applicant attraction to flexible work arrangements: Separating the influence of flextime and flexplace. J. Occup. Organ. Psychol. 2015, 88, 726–749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Greening, D.W. Corporate social performance and organizational attractiveness to prospective employees. Acad. Manag. J. 1997, 40, 658–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lis, B. The relevance of corporate social responsibility for a sustainable human resource management: An analysis of organizational attractiveness as a determinant in employees’ selection of a (potential) employer. Manag. Rev. 2012, 23, 279–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Anderson, M.H.; Haar, J.M.; Gibb, J.L. Personality trait inferences about organizations and organizational attraction: An organizational-level analysis based on a multi-cultural sample. J. Manag. Organ. 2010, 16, 140–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rindova, V.P.; Williamson, I.O.; Petkova, A.P.; Sever, J.M. Being good or beeing known: An empirical examination of the acendents, and consequences of organizational reputation. Acad. Manag. J. 2005, 48, 1033–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Williamson, I.O.; King, J.E.; Lepak, D.; Sarma, A. Firm reputation, recruitment web sites, and attracting applicants. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2010, 49, 669–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duarte, A.P.; Gomes, D.R.; das Neves, J.G. Tell me your socially responsible practices, I will tell you how attractive for recruitment you are the impact of perceived CSR on organizational attractiveness. Tékhne 2014, 12, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, D.A.; Willness, C.R.; Madey, S. Why are job seekers attracted by corporate social performance? Experimental and field tests of three signal-based mechanisms. Acad. Manag. J. 2014, 57, 383–404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turban, D.B.; Forret, M.L.; Hendrickson, C.L. Applicant attraction to firms: Influences of organization reputation, job and organizational attributes, and recruiter behaviors. J. Vocat. Behav. 1998, 44, 24–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Behrend, T.S.; Baker, B.A.; Thompson, L.F. Effects of pro-environmental recruiting messages: The role of organizational reputation. J. Bus. Psychol. 2009, 24, 341–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baum, M.; Kabst, R. The effectiveness of recruitment advertisements and recruitment websites: Indirect and interactive effects on applicant attraction. Hum. Resour. Manag. 2014, 53, 353–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shrout, P.E.; Bolger, N. Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychol. Methods 2002, 7, 422–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mackinnon, D.P.; Krull, J.L.; Lockwood, C.M. Equivalence of the Mediation, Confounding and Suppression Effect. Prev. Sci. 2000, 1, 173–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Edwards, J.R.; Lambert, L.S. Methods for integrating moderation and mediation: A general analytical framework using moderated path analysis. Psychol. Methods 2007, 12, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Banks, G.C.; Kepes, S.; Joshi, M.; Seers, A. Social identity and applicant attraction: Exploring the role of multiple levels of self. J. Organ. Behav. 2015, 37, 326–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glavas, A.; Godwin, L.N. Is the perception of ‘goodness’ good enough? Exploring the relationship between perceived corporate social responsibility and employee organizational identification. J. Bus. Ethics 2013, 114, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brooks, M.E.; Highhouse, S.; Russell, S.S.; Mohr, D.C. Familiarity, ambivalence, and firm reputation: Is corporate fame a double-edged sword? J. Appl. Psychol. 2003, 88, 904–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falkenreck, C. Reputation Transfer to Enter New B-to-B Markets: Measuring and Modelling Approaches, 1st ed.; Springer Science & Business Media: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Waight, P.; Chow, J. Employer Branding in Australia: A content analysis of recruitment advertising in the mining and higher education industries. In Proceedings of the 23rd ANZAM Conference 2009: Sustainable Management and Marketing, Melbourne, Australia, 1–4 December 2009; Promaco Conventions Pty Ltd.: Bateman, WA, Australia, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social the moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Highhouse, S.; Thornbury, E.E.; Little, I.S. Social-identity functions of attraction to organizations. Organ. Behav. Hum. Decis. Process 2007, 103, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenberg, M. Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, Society and the Adoslescent Self-Image; University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA; New York, NY, USA, 1965. [Google Scholar]

- Pierce, J.L.; Gardner, D.G. Self-esteem within the work and organizational context: A review of the organization-based self-esteem literature. J. Manag. 2004, 30, 591–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brockner, J. Self-Esteem at Work; Lexington Books: Lexington, MA, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J.D. Self-esteem and clarity of the self-concept. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1990, 59, 538–549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ashforth, B.E.; Mael, F. Social identity theory and the organization. J. Bus. Ethics 1989, 14, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutton, J.E.; Dukerich, J.M.; Harquail, C.V. Organizational images and member identification. Adm. Sci. Q. 1994, 39, 239–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- ManpowerGroup. Talent Shortage; ManpowerGroup: Milwaukee, WI, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Lievens, F.; Highhouse, S. The relation of instrumental and symbolic attributes to a company’s attractiveness as an employer. Pers. Psychol. 2003, 56, 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. SPSS and SAS procedures for estimating indirect effects in simple mediation models. Behav. Res. Methods Instrum. Comput. 2004, 36, 717–731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Preacher, K.J.; Hayes, A.F. Asymptotic and resampling strategies for assessing and comparing indirect effects in multiple mediator models. Behav. Res. Methods 2008, 40, 879–891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aiken, L.S.; West, S.G. Multiple Regression: Testing and Interpreting Interactions; Sage: Newbury Park, CA, USA, 1996. [Google Scholar]

| Equation | T Statistics | Std Error | LL | UL | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ai | 36.1031 ** | 0.0267 | 0.9105 | 1.0155 | H2 Supported |

| bi | −2.8804 ** | 0.0830 | −0.4024 | −0.0758 | |

| c’ | 9.4173 ** | 0.0918 | 0.6839 | 1.0451 | H1 Supported |

| b2i | 6.7312 ** | 0.0443 | 0.2108 | 0.3849 | |

| b3i | −2.1962 * | 0.0479 | −0.1995 | −0.0110 | H3 Supported |

| Self-Esteem | Effect | BootSE | BootLLCI | BootULCI | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indirect Effect | Low | −0.1572 | 0.0901 | −0.3289 | −0.0246 | |

| Medium | −0.2302 | 0.0839 | −0.3943 | −0.0600 | ||

| High | −0.3033 | 0.0863 | −0.4718 | −0.1324 | ||

| Mediated Moderation | −0.1013 | 0.0377 | −0.1816 | −0.0311 | H4 not Supported |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bustaman, H.A.; Taha, A.Z.B.; Nor, M.N.B.M.; Aslam, M.Z.; Yousif, M.M.M. The Organizational Justice and Organizational Reputation Attracting Digital Natives with High Self-Esteem. Proceedings 2022, 82, 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2022082112

Bustaman HA, Taha AZB, Nor MNBM, Aslam MZ, Yousif MMM. The Organizational Justice and Organizational Reputation Attracting Digital Natives with High Self-Esteem. Proceedings. 2022; 82(1):112. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2022082112

Chicago/Turabian StyleBustaman, Hasnun Anip, Azni Zarina Binti Taha, Mohammad Nazri Bin Mohd Nor, Muhammad Zia Aslam, and Mohammed Mustafa Mohammed Yousif. 2022. "The Organizational Justice and Organizational Reputation Attracting Digital Natives with High Self-Esteem" Proceedings 82, no. 1: 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2022082112

APA StyleBustaman, H. A., Taha, A. Z. B., Nor, M. N. B. M., Aslam, M. Z., & Yousif, M. M. M. (2022). The Organizational Justice and Organizational Reputation Attracting Digital Natives with High Self-Esteem. Proceedings, 82(1), 112. https://doi.org/10.3390/proceedings2022082112