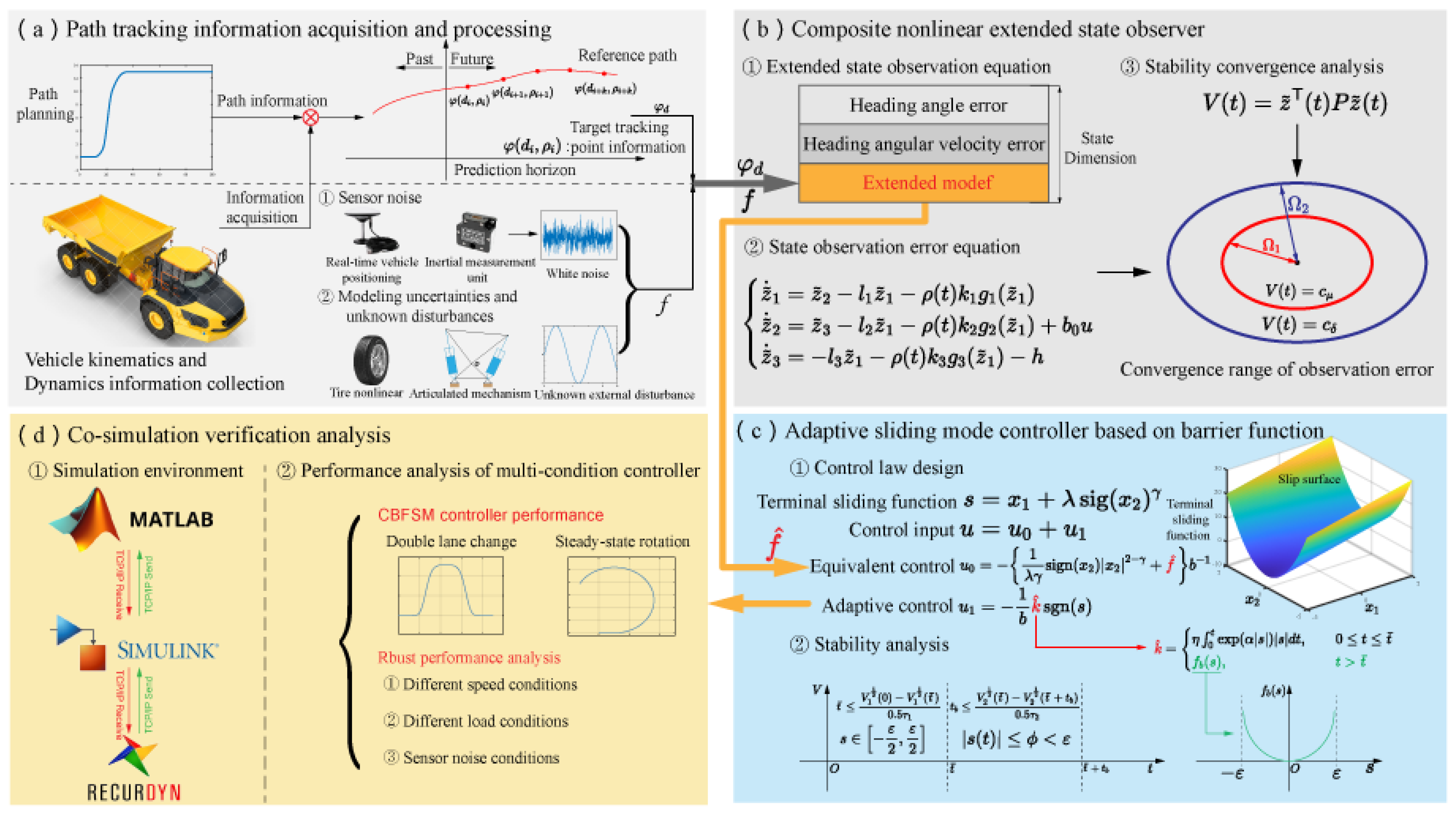

A Composite Barrier Function Sliding Mode Control Method Based on an Extended State Observer for the Path Tracking of Unmanned Articulated Vehicles

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Modeling of Mathematical Model and Path Tracking Error Model

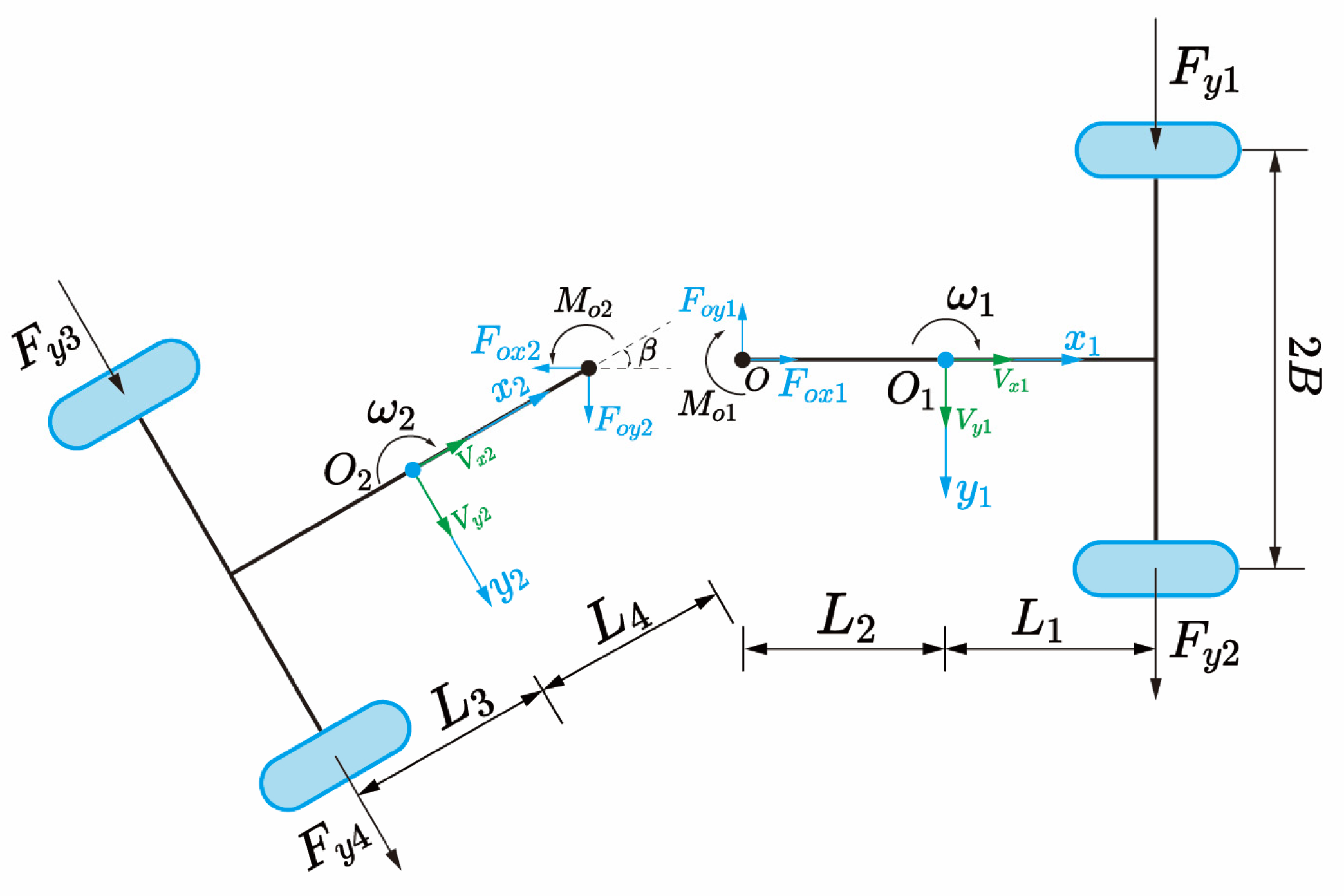

2.1. Nonlinear Kinematics and Dynamics Model of Unmanned Articulated Vehicle

2.1.1. Modeling of Kinematics for Unmanned Articulated Vehicle

2.1.2. Nonlinear Dynamic Model of Unmanned Articulated Vehicle

- The front and rear vehicle bodies are rigid bodies, ignoring the influence of force on the deformation of the vehicle body.

- The centroids of the front and rear vehicle bodies are located on the longitudinal center axis, and the vehicle is symmetrical about the longitudinal center axis.

- The influences of tire camber angle and aligning torque on the dynamic characteristics of the wheel are ignored.

- Air resistance is ignored, and the road surface is flat.

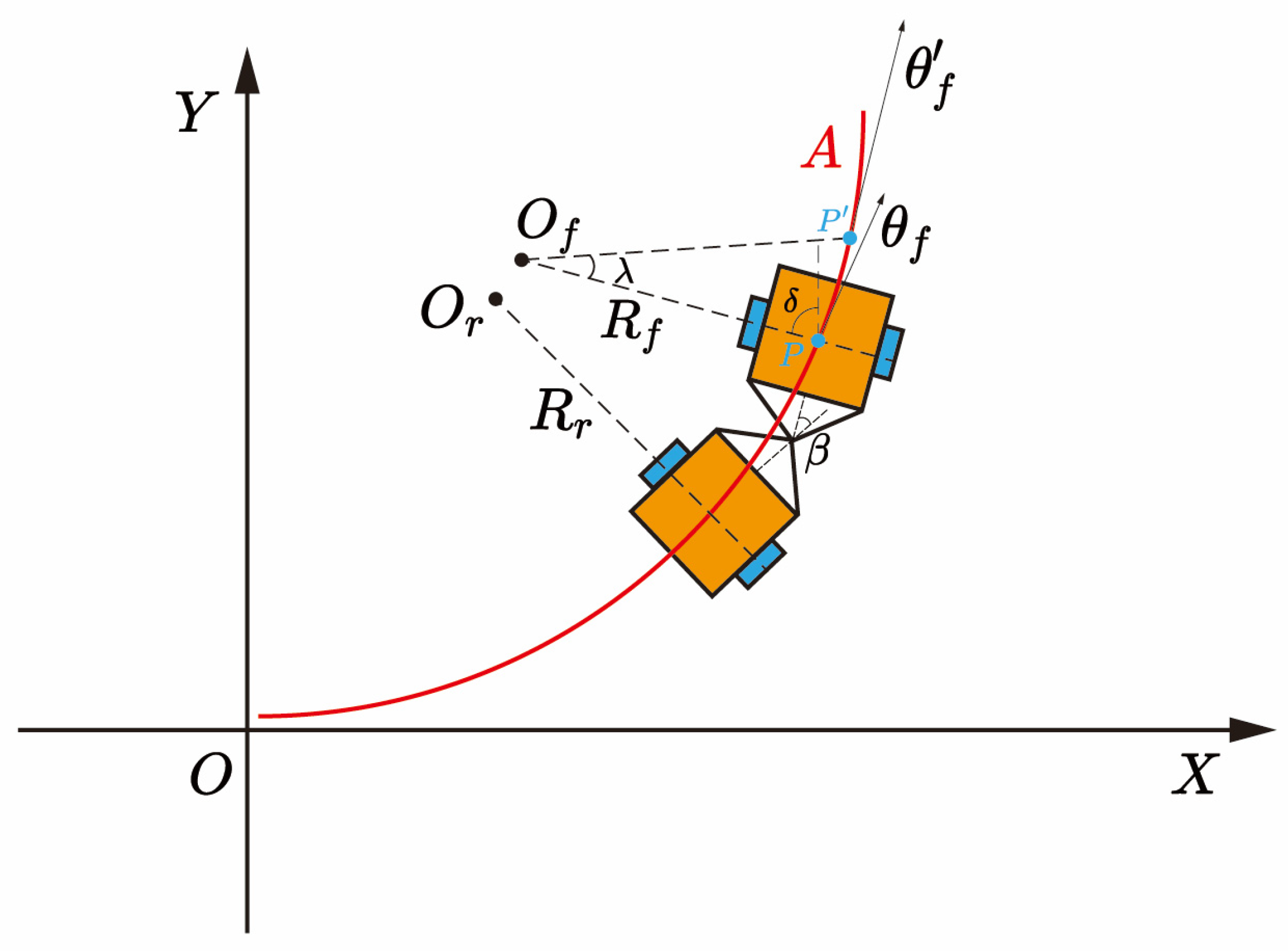

2.2. Path Tracking Error Model

2.2.1. Path Tracking Expected Heading Angle

2.2.2. Comprehensive Expected Heading Angle in Prediction Horizon

3. Composite Barrier Function Sliding Mode Control Based on an Extended State Observer

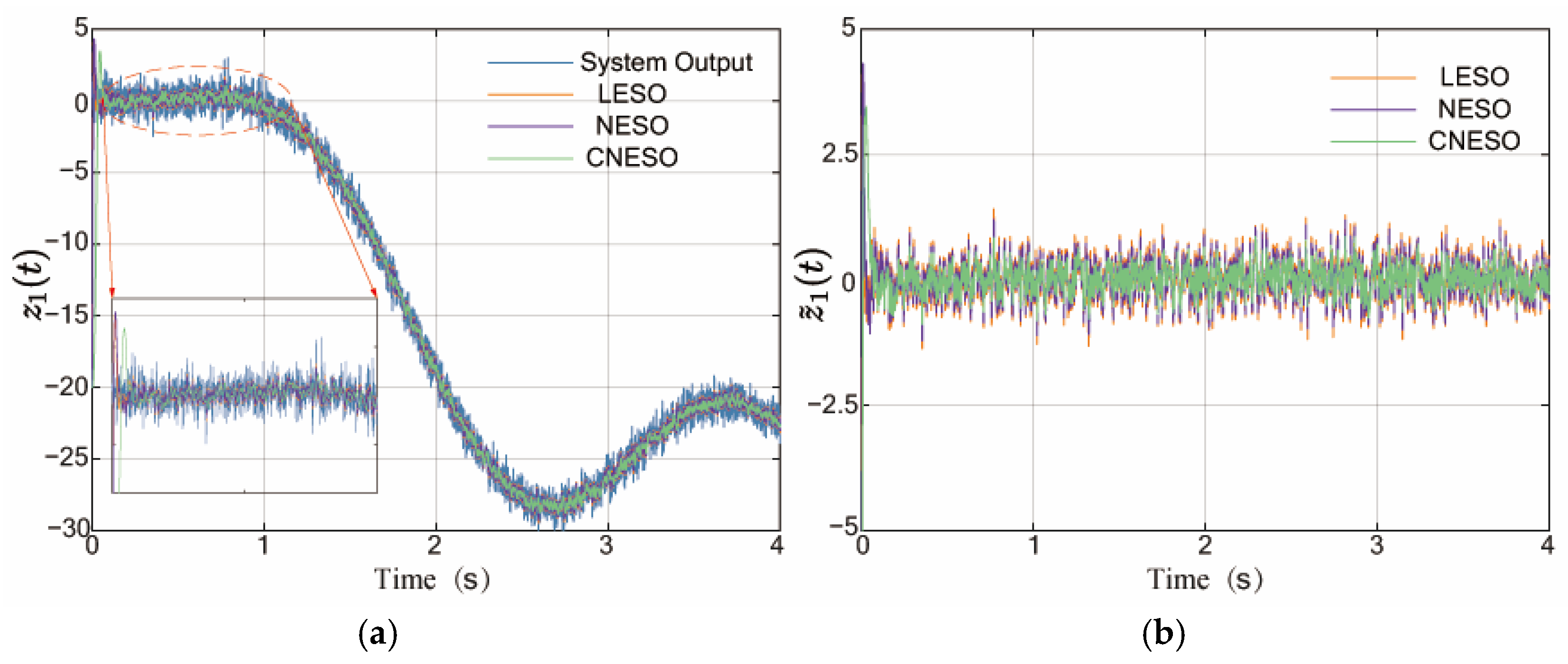

3.1. Design and Performance Analysis of Composite Nonlinear Extended State Observer

3.1.1. Design of Disturbance Observer

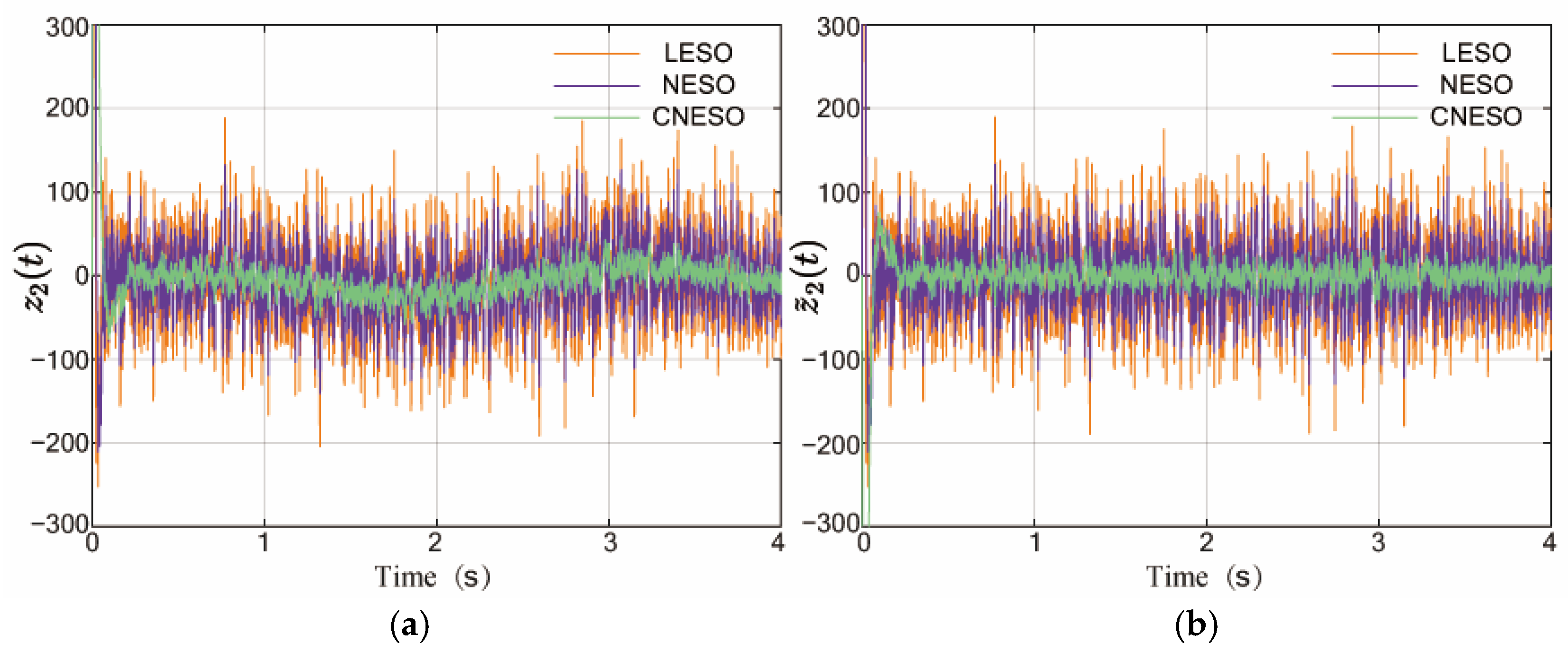

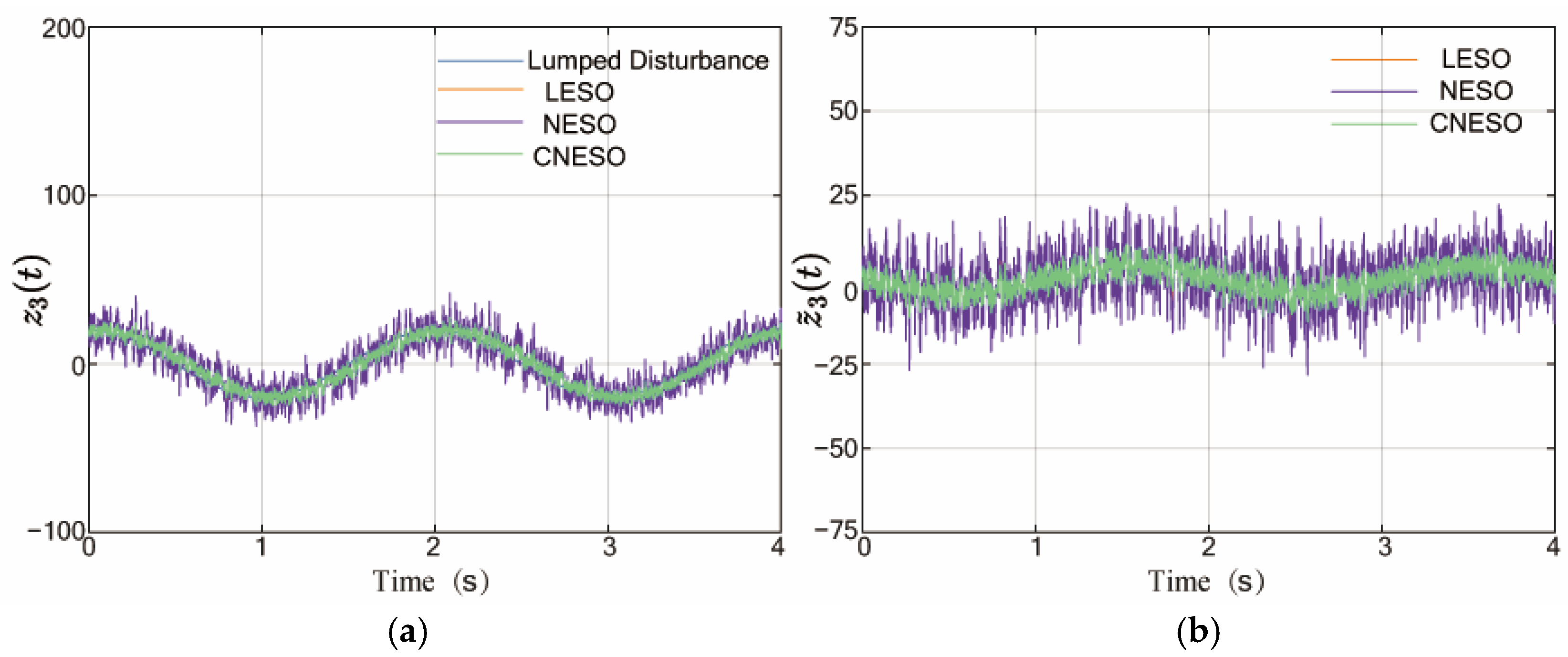

3.1.2. Analysis of Simulation Performance

3.2. Design of Adaptive Sliding Mode Controller Based on Barrier Function

3.3. Verification Analysis of Joint Simulation

3.3.1. Comparative Analysis of CBFSMC Controller Performance

- Working condition of double lane change

- 2.

- Work condition of steady-state rotation

3.3.2. Robust Performance Analysis of CBFSMC Controller

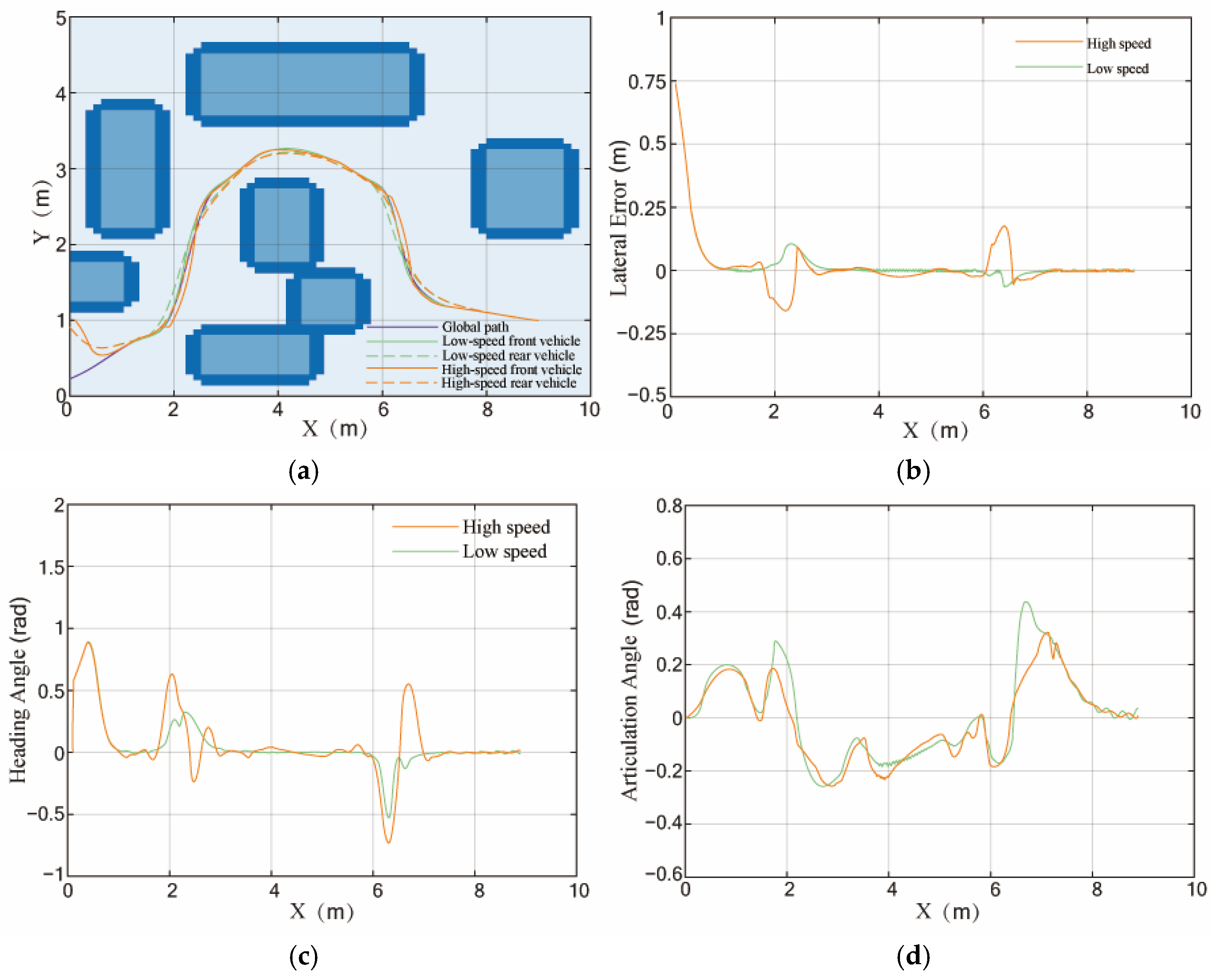

- Work condition of different speeds

- 2.

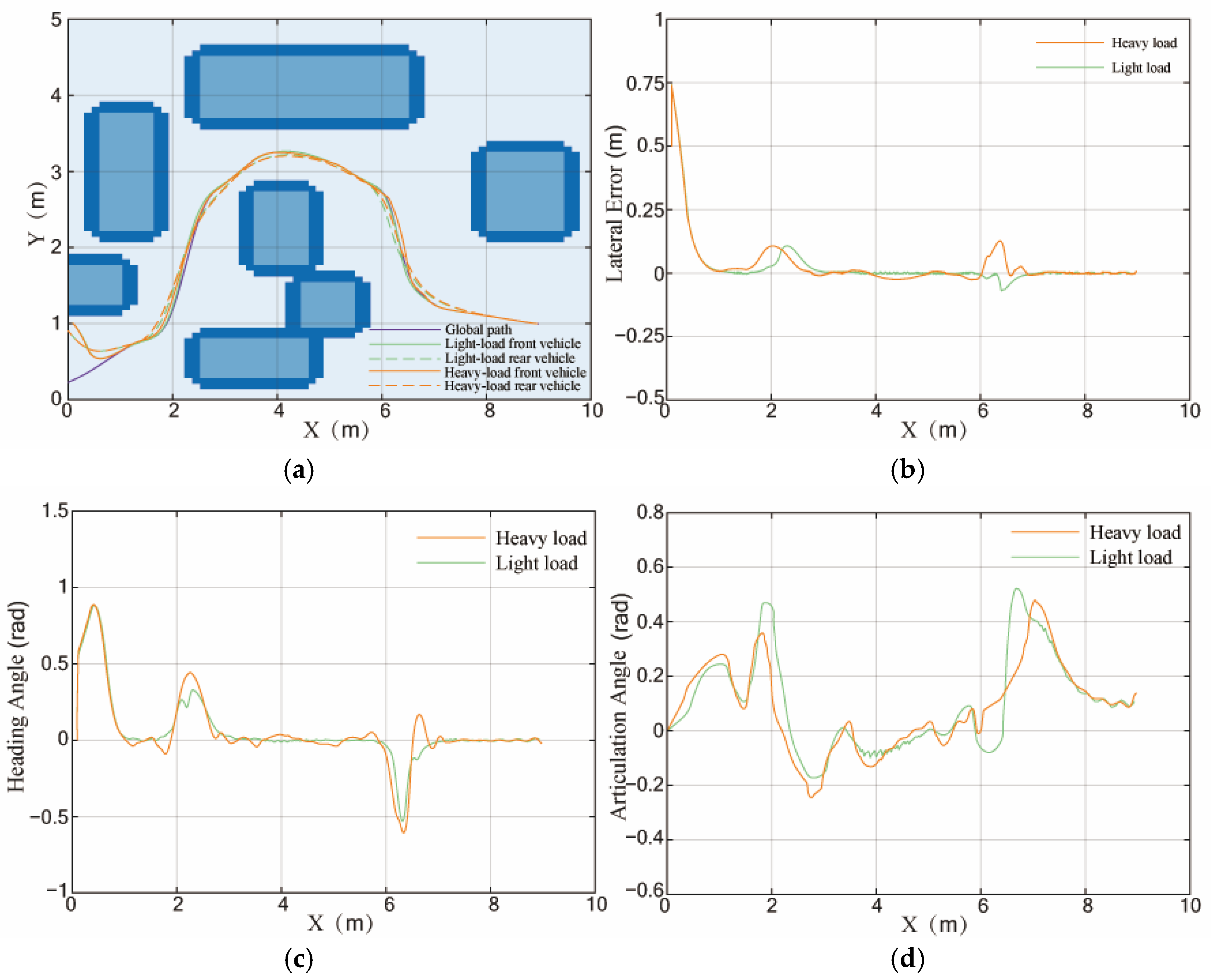

- Work condition of different loads

- 3.

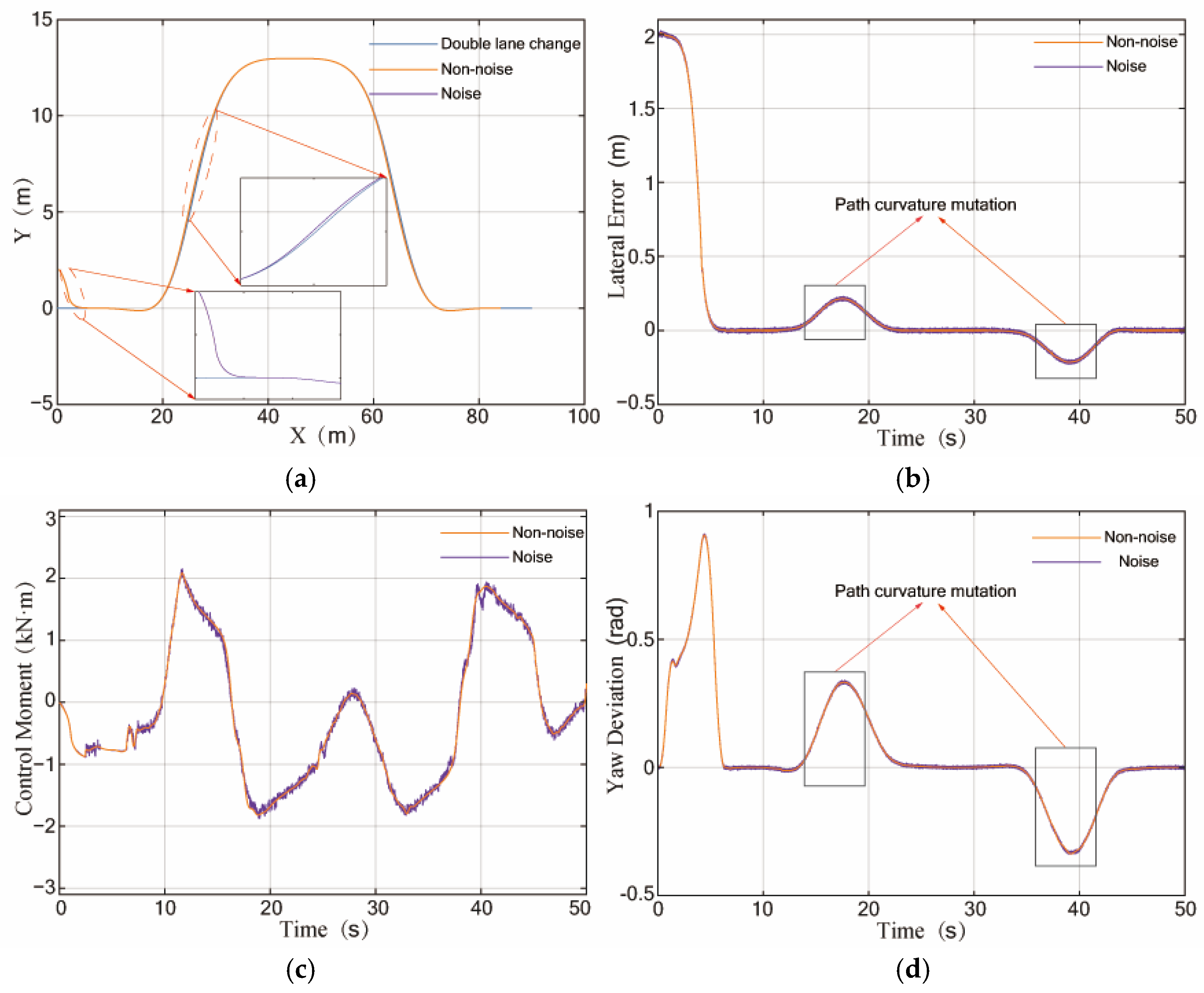

- Work condition of sensor noise

4. Experimental Validation

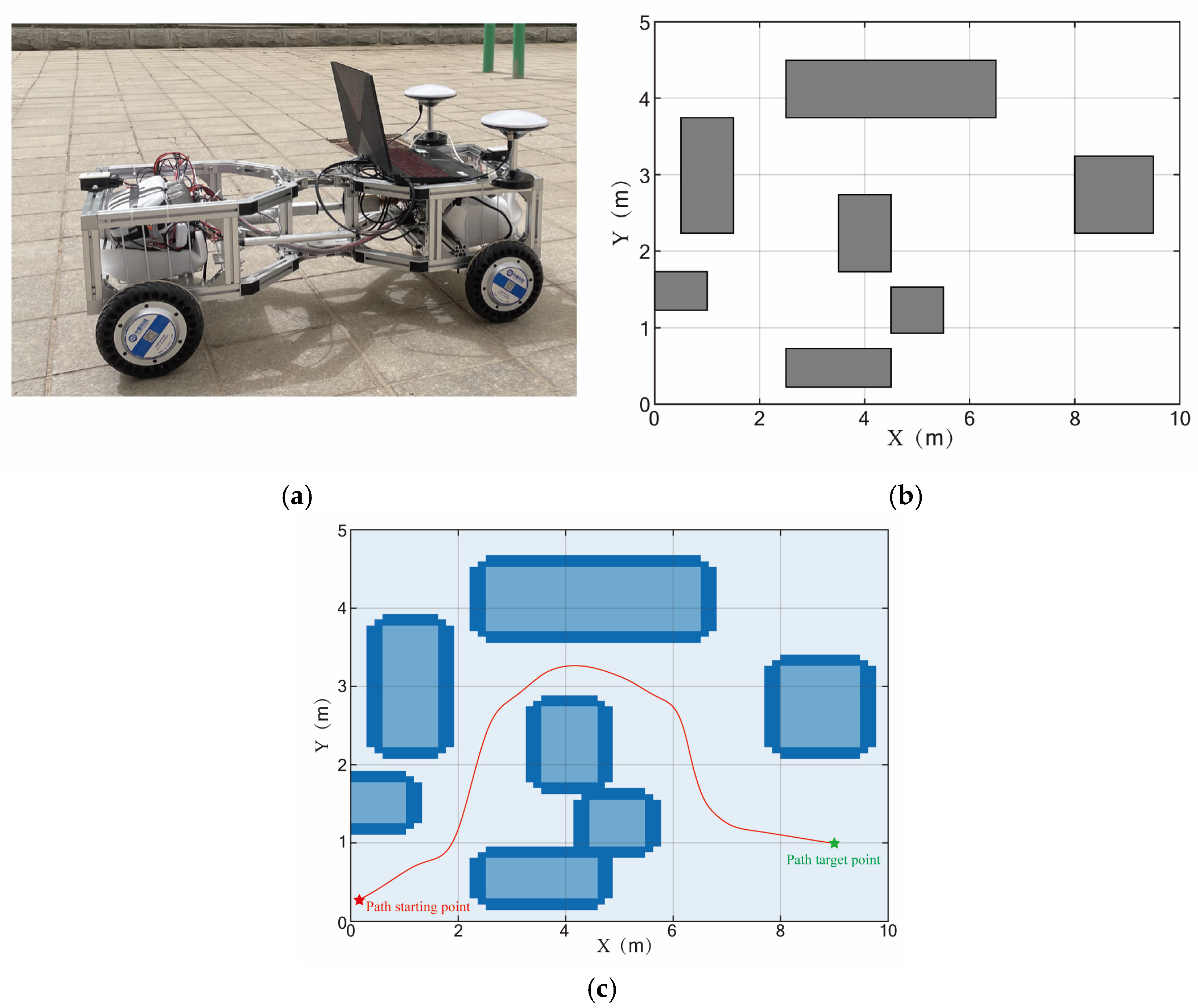

4.1. Introduction to Prototype Platform of Unmanned Articulated Vehicle

4.2. Experimental Verification of Path Tracking Method

4.2.1. Path Tracking Test Under Different Speed Conditions

4.2.2. Path Tracking Tests Under Different Load Conditions

5. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

| Coordinates of the midpoint of the front axles | |

| Coordinates of the midpoint of the rear axles | |

| Speed of the center of mass of the front vehicles | |

| Speed of the center of mass of the rear vehicles | |

| Distance from the hinge point to the midpoint of the front axles | |

| Distance from the hinge point to the midpoint of the rear axles | |

| Hinge angle | |

| Steering radius of the front vehicle bodies | |

| Steering radius of the rear vehicle bodies | |

| O | Hinge point of the front and rear vehicle bodies |

| Centroid positions of the front vehicle bodies | |

| Centroid positions of the rear vehicle bodies | |

| Body coordinate system of the front vehicle body | |

| Body coordinate system of the rear vehicle body | |

| Lateral velocities of the front and rear vehicle bodies | |

| Longitudinal velocities of the front and rear vehicle bodies | |

| Yaw angular velocity of the front and rear vehicle bodies | |

| Longitudinal force of four wheels | |

| Lateral force of the four wheels | |

| Steering torque of the articulated steering system to the front vehicle bodies | |

| Steering torque of the articulated steering system to the rear vehicle bodies | |

| Longitudinal forces of the articulated points of the front and rear vehicle bodies to the front and rear vehicle bodies | |

| Lateral forces of the articulated points of the front and rear vehicle bodies to the front and rear vehicle bodies | |

| 2B | Width of the front and rear vehicle bodies |

| Distances from the center of mass of the front and rear vehicle bodies to the tires and hinge points ( = 1, 2, 3, 4) | |

| β | Folding angle between the front and rear vehicle bodies |

| Yaw rate of the front vehicle bodies | |

| Yaw rate of the rear vehicle bodies | |

| Mass of the front vehicle bodies | |

| Mass of the rear vehicle bodies | |

| Moment of inertia of the front and rear vehicle bodies around | |

| Moment of inertia of the front and rear vehicle bodies around | |

| Tire cornering stiffness | |

| Tire cornering angle during vehicle | |

| R | Tracking reference path |

| P | Centroid of the articulated vehicle front body |

| Predicted vehicle position | |

| M | Orthogonal projection of P to the reference path |

| α | Vehicle’s sideslip angle |

| Horizontal axes in the Serret–Frenet coordinate system | |

| Vertical axes in the Serret–Frenet coordinate system | |

| M | Origin |

| Distance between M and P | |

| Reference heading angle at the reference point M | |

| s | Arc length between M and a point on R |

| c(s) | Curvature of the M point on the reference path R |

| Steering centers of front vehicle bodies | |

| Steering centers of rear vehicle bodies | |

| Heading angles of front vehicle bodies | |

| Heading angles of rear vehicle bodies | |

| Time interval in prediction horizon | |

| Steering angular velocity of front body moving from point P to point P′ | |

| δ | Deviation between heading angle at next moment and current moment |

| Comprehensive weight | |

| Path tracking control target | |

| y | Represents system output |

| Control input of system, | |

| Unmodeled dynamics of system and external disturbances | |

| f | Total lumped disturbance of the entire system |

| ω(t) | White noise |

| Estimation error | |

| The estimates of ( = 1, 2, 3) | |

| Observer gain of ( = 1, 2, 3) | |

| s | Sliding variable |

| Equivalent control term | |

| Adaptive control term | |

| Adaptive control gain to be designed | |

| c | Region boundary of final convergence of tracking error |

| Sampling interval | |

| r | Adjustable parameter |

Abbreviations

| PID | Proportional integral derivative |

| PSO-LQR | Particle swarm optimization linear quadratic regulator |

| MPC | Model predictive control |

| ROS | Robot operating system |

| DOF | Degree of freedom |

| CNESO | Composite nonlinear extended state observer |

| ESO | Extended state observer |

| CBFSMC | Composite barrier function sliding mode controller |

| BF | Barrier function |

| LESO | Linear extended state observer |

| NESO | Nonlinear extended state observer |

| NTSM | Nonsingular terminal sliding mode |

| ADRC | Active disturbance rejection control |

| IMU | Inertial measurement unit |

| SNR | Signal-to-noise ratio |

| CAN | Controller area network |

| RTK | Real-time kinematic |

Appendix A

- If , by substituting Equation (34) into Equation (35), the following can be obtained:

- 2.

- If , substituting Equation (34) into Equation (31) gives the following:

- When the adaptive law in Equation (38) is applied within the time interval .

- 2.

- When the adaptive law in Equation (38) is applied within the time interval .

References

- Hung, N.; Rego, F.; Quintas, J.; Cruz, J.; Jacinto, M.; Souto, D.; Potes, A.; Sebastiao, L.; Pascoal, A. A review of path following control strategies for autonomous robotic vehicles: Theory, simulations, and experiments. J. Field Robot. 2023, 40, 747–779. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, X. Research on Path Planning and Path Tracking Control Methods for Articulated Wheeled Operating Vehicles. Master’s Thesis, Jilin University, Changchun, China, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Liao, K.; Liou, J.; Hidayat, M.; Wen, H.-T.; Wu, H.-Y. Detection and Analysis of Aircraft Composite Material Structures Using UAV. Inventions 2024, 9, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, Q.; Gao, L.; Xie, H.; Dou, F. Analysis of the Dynamic Modeling Method of Articulated Vehicles. J. Eng. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2017, 10, 18–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazooki, A.; Rakheja, S.; Cao, D. A three-dimensional model of an articulated frame-steer vehicle for coupled ride and handling dynamic analyses. Int. J. Veh. Perform. 2014, 1, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, L.; Jin, C.; Liu, Y.; Ma, F.; Feng, Z. Hybrid Model-Based Analysis of Underground Articulated Vehicles Steering Characteristics. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 5274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dudziński, P.; Skurjat, A. Impact of Hydraulic System Stiffness on Its Energy Losses and Its Efficiency in Positioning Mechanical Systems. Energies 2022, 15, 294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Chen, H. MPC-based path tracking with PID speed control for autonomous vehicles. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 892, 012034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, Y.; Wen, X.; Zhang, G.; Ma, Q.; Cheng, S.; Qi, J.; Xu, L.; Chen, L. An optimal goal point determination algorithm for automatic navigation of agricultural machinery: Improving the tracking accuracy of the Pure Pursuit algorithm. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2022, 194, 106760. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Gao, F.; Zhao, F. Research on Path Planning and Tracking Control of Autonomous Vehicles Based on Improved RRT* and PSO-LQR. Processes 2023, 11, 1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, T.; Zhao, R. LQR-MPC-Based Trajectory-Tracking Controller of Autonomous Vehicle Subject to Coupling Effects and Driving State Uncertainties. Sensors 2022, 22, 5556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, N.; Zhang, W.; Yang, J. Integrated Path Tracking Controller of Underground Articulated Vehicle Based on Nonlinear Model Predictive Control. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 5340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Cheng, J.; Hu, H.; Shao, G.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, Q. A Novel Fuzzy Logic Switched MPC for Efficient Path Tracking of Articulated Steering Vehicles. Robotics 2024, 13, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.; Gu, X.; Zhang, K.; Li, X.; Wang, J. PSO-Based Variable Parameter Linear Quadratic Regulator for Articulated Vehicles Snaking Oscillation Yaw Motion Control. Actuators 2022, 11, 337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piyabongkarn, D.; Rajamani, R.; Grogg, J.A.; Lew, J.Y. Development and Experimental Evaluation of a Slip Angle Estimator for Vehicle Stability Control. IEEE Trans. Control Syst. Technol. 2009, 17, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doumiati, M.; Victorino, A.C.; Charara, A.; Lechner, D. Onboard Real-Time Estimation of Vehicle Lateral Tire–Road Forces and Sideslip Angle. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2011, 16, 601–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, S.; Peng, H. Design, Analysis, and Experiments of Preview Path Tracking Control for Autonomous Vehicles. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2020, 21, 48–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, J. From PID to Active Disturbance Rejection Control. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2009, 56, 900–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, B.; Lee, T.; Peng, K.; Venkataramanan, V. Composite nonlinear feedback control for linear systems with input saturation: Theory and an application. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control 2003, 48, 427–439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.Q.; Gaol, L.; Gao, Z. On stability analysis of active disturbance rejection control for nonlinear time-varying platns with unknown dynamics. In Proceedings of the 2007 46th IEEE Conference on Decision and Control, New Orleans, LA, USA, 12–14 December 2007; pp. 3501–3506. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, Z.; Zheng, J.; Man, Z.; Wang, H. Adaptive fast non-singular terminal sliding mode control for a vehicle steer-by-wire system. IET Control Theory Appl. 2017, 11, 1245–1254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, J.; Wang, H.; Man, Z.; Jin, J.; Fu, M. Robust Motion Control of a Linear Motor Positioner Using Fast Nonsingular Terminal Sliding Mode. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2015, 20, 1743–1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallaha, C.J.; Saad, M.; Kanaan, H.Y.; Al-Haddad, K. Sliding-Mode Robot Control With Exponential Reaching Law. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2011, 58, 600–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Wang, L.; Zhang, J.; Li, F. Path Following Control of Autonomous Ground Vehicle Based on Nonsingular Terminal Sliding Mode and Active Disturbance Rejection Control. IEEE Trans. Veh. Technol. 2019, 68, 6379–6390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Xie, H.; Zheng, J.; Man, Z.; He, D. Path-following control of Mecanum-wheels omnidirectional mobile robots using nonsingular terminal sliding mode. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2021, 147, 107128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Xu, G. A Novel Non-Singular Terminal Sliding Mode Trajectory Tracking Control for Robotic Manipulators. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2021, 68, 391–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Ortiz, D.; Chairez, I.; Poznyak, A. Non-singular terminal sliding-mode control for a manipulator robot using a barrier Lyapunov function. ISA Trans. 2022, 121, 268–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kang, N.; Han, Y.; Guan, T.; Wang, S. Improved ADRC-Based Autonomous Vehicle Path-Tracking Control Study Considering Lateral Stability. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 4660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, Y.; Pu, F.; Li, S.; Gao, Y. Lateral Path Tracking Control of Autonomous Land Vehicle Based on ADRC and Differential Flatness. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 3091–3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Observer | The Value of the Parameter | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNESO | ||||

| LESO | ||||

| NESO | ||||

| Observation Status | Observer | Average Error | Maximum Error | Root Mean Square Error |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LESO | 0.649 | 1.414 | 0.806 | |

| NESO | 0.619 | 1.214 | 0.787 | |

| CNESO | 0.567 | 0.888 | 0.763 | |

| LESO | 43.228 | 189.302 | 54.006 | |

| NESO | 30.791 | 133.372 | 38.528 | |

| CNESO | 9.239 | 38.672 | 11.554 | |

| LESO | 4.826 | 21.614 | 6.027 | |

| NESO | 6.196 | 28.170 | 7.764 | |

| CNESO | 3.273 | 12.527 | 3.970 |

| Controller | The Value of the Parameter | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CBFSMC | ||||

| NTSM | ||||

| ADRC | ||||

| Controller | Convergence Time (s) | Average Error (m) | Steady-State Maximum Error (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADRC | 9.53 | 0.313 | 0.652 |

| NTSM | 6.38 | 0.322 | 0.692 |

| CBFSMC | 5.58 | 0.202 | 0.215 |

| Controller | Convergence Time (s) | Average Error (m) | Steady-State Maximum Error (m) |

|---|---|---|---|

| ADRC | 9.26 | 0.317 | 0.052 |

| NTSM | 7.73 | 0.324 | 0.067 |

| CBFSMC | 5.57 | 0.261 | 0.011 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zhang, K.; Gu, X.; Wang, N.; Cao, J.; Wang, J.; Zhang, S.; Li, X. A Composite Barrier Function Sliding Mode Control Method Based on an Extended State Observer for the Path Tracking of Unmanned Articulated Vehicles. Drones 2025, 9, 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9030182

Zhang K, Gu X, Wang N, Cao J, Wang J, Zhang S, Li X. A Composite Barrier Function Sliding Mode Control Method Based on an Extended State Observer for the Path Tracking of Unmanned Articulated Vehicles. Drones. 2025; 9(3):182. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9030182

Chicago/Turabian StyleZhang, Kanghua, Xiaochao Gu, Nan Wang, Jialu Cao, Jixin Wang, Shaokai Zhang, and Xiang Li. 2025. "A Composite Barrier Function Sliding Mode Control Method Based on an Extended State Observer for the Path Tracking of Unmanned Articulated Vehicles" Drones 9, no. 3: 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9030182

APA StyleZhang, K., Gu, X., Wang, N., Cao, J., Wang, J., Zhang, S., & Li, X. (2025). A Composite Barrier Function Sliding Mode Control Method Based on an Extended State Observer for the Path Tracking of Unmanned Articulated Vehicles. Drones, 9(3), 182. https://doi.org/10.3390/drones9030182