Three Hundred and Sixty Degree Real-Time Monitoring of 3-D Printing Using Computer Analysis of Two Camera Views

Abstract

:1. Introduction

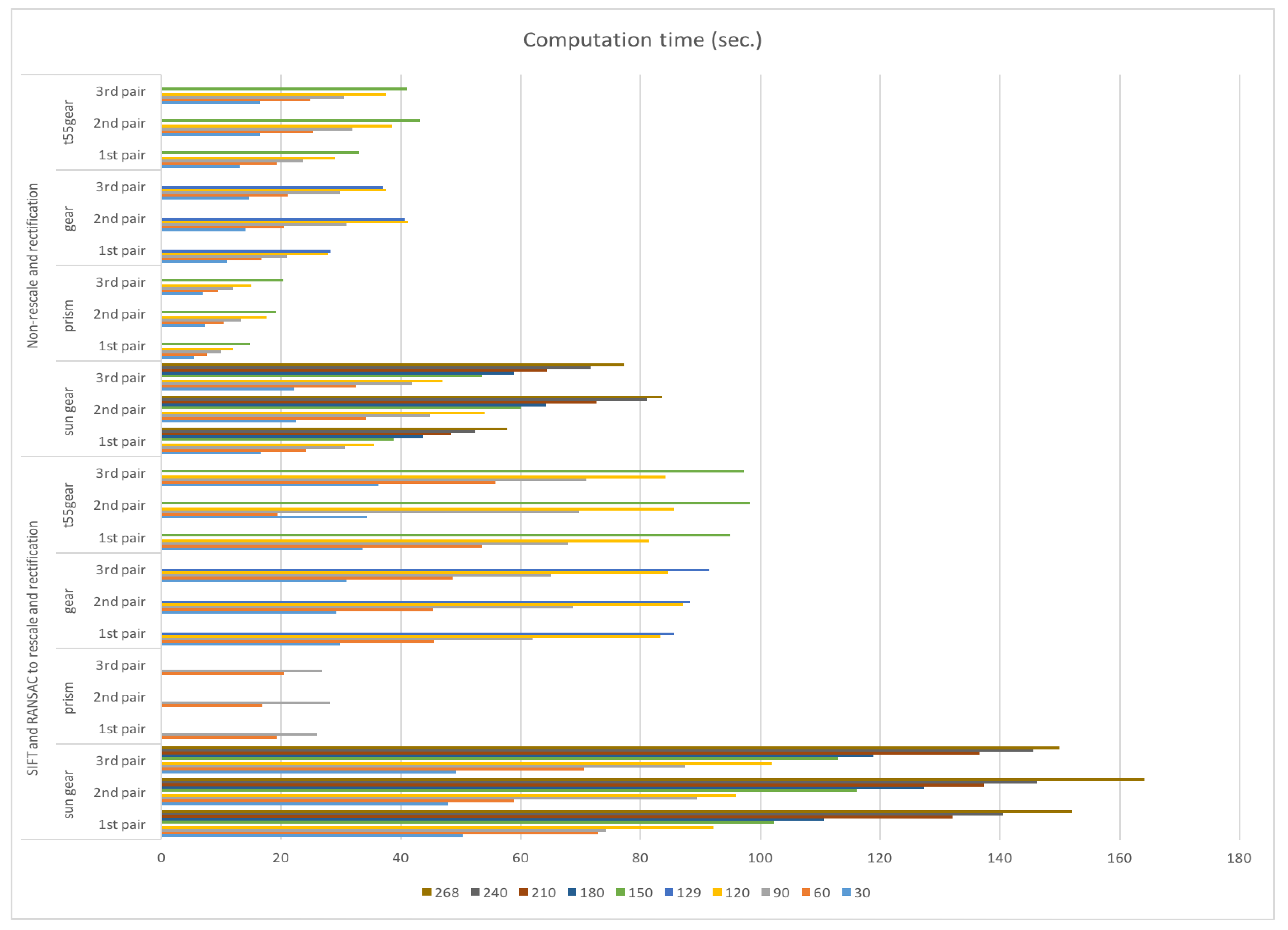

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Experimental Equipment

2.2. Theory

2.2.1. Calculating Webcam Pixel Size and Focal Length

2.2.2. Computer Vision Error Detection

2.3. Experiments

2.3.1. Image Pre-Processing

SIFT and RANSAC to Rescale and Rectification

With Non-Rescale and Rectification

2.3.2. Error Detection

Horizontal Magnitude

Horizontal and Vertical Magnitude

2.4. Validation

3. Results

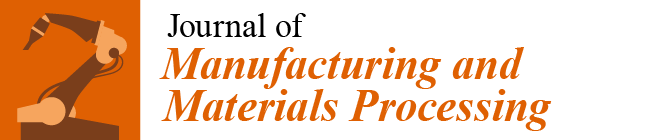

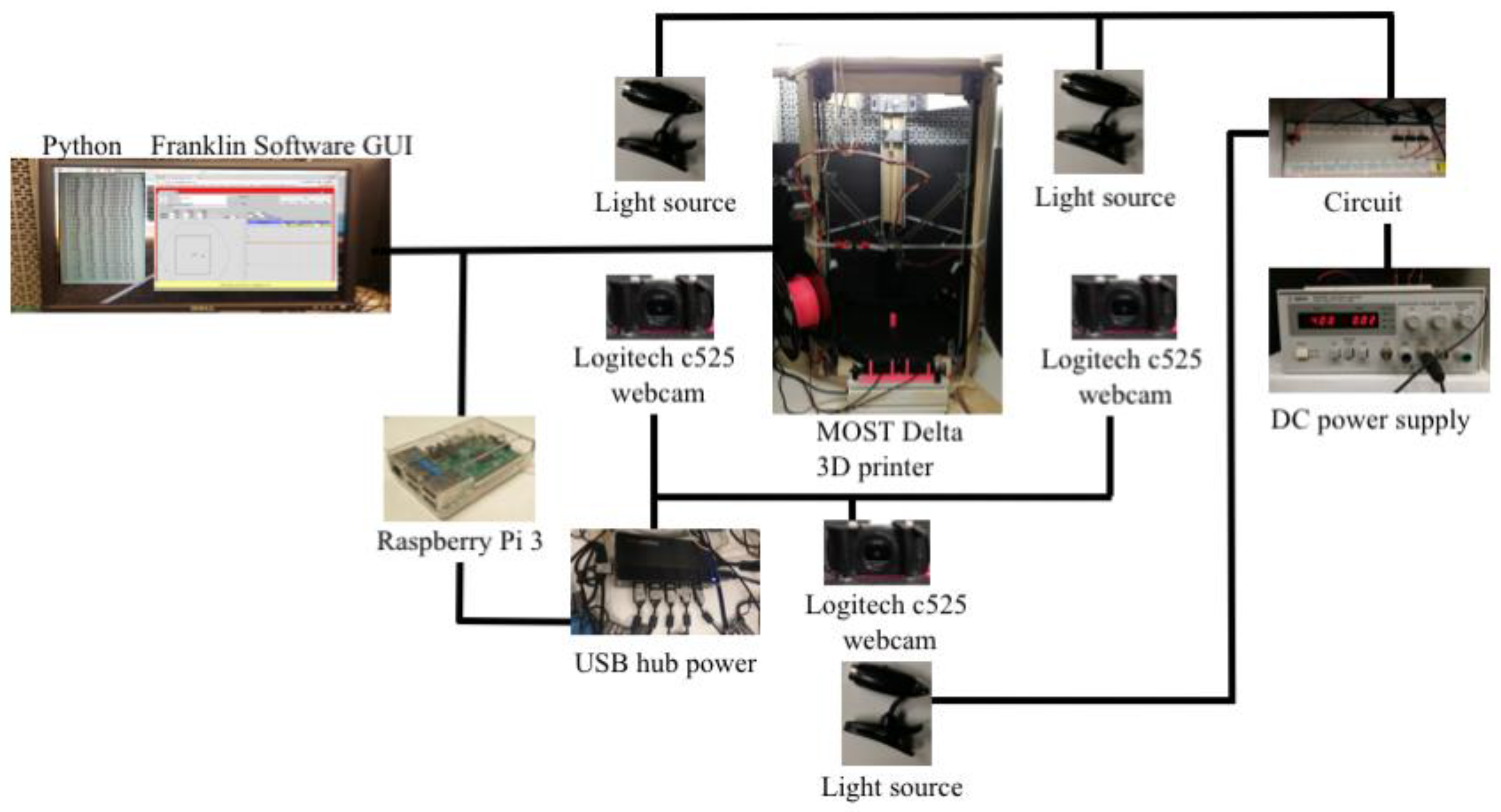

3.1. Image Pre-Processing

3.1.1. SIFT and RANSAC to Rescale and Rectification

Normal Printing State

Failure Printing State

3.1.2. With Non-Rescale and Rectification

Normal Printing State

Failure Printing State

3.2. Error Detection

3.2.1. Horizontal Magnitude

3.2.2. Horizontal and Vertical Magnitude

Normal Printing State

Failure Printing State

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Author Contributions

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

References

- Wohlers, T. Wohlers Report 2016; Wohlers Associates, Inc.: Fort Collins, CO, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Sells, E.; Smith, Z.; Bailard, S.; Bowyer, A.; Olliver, V. RepRap: The Replicating Rapid Prototyper: Maximizing Customizability by Breeding the Means of Production. In Handbook of Research in Mass Customization and Personalization: Strategies and Concepts; Piller, F.T., Tseng, M.M., Eds.; World Scientific: Singapore, 2010; Volume 1, pp. 568–580. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, R.; Haufe, P.; Sells, E.; Iravani, P.; Olliver, V.; Palmer, C.; Bowyer, A. RepRap—The replicating rapid prototyper. Robotica 2011, 29, 177–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bowyer, A. 3D Printing and Humanity’s First Imperfect Replicator. 3D Print. Addit. Manuf. 2014, 1, 4–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibb, A.; Abadie, S. Building Open Source Hardware: DIY Manufacturing for Hackers and Makers; Addison Wesley: Boston, MA, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, E. The cathedral and the bazaar. Knowl. Technol. Policy 1999, 12, 23–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Make. 3D Printer Shootout News, Reviews and More|Make: DIY Projects and Ideas for Makers [WWW Document]. 2017. Available online: http://makezine.com/tag/3d-printer-shootout/ (accessed on 11 April 2017).

- Wittbrodt, B.T.; Glover, A.G.; Laureto, J.; Anzalone, G.C.; Oppliger, D.; Irwin, J.L.; Pearce, J.M. Life-cycle economic analysis of distributed manufacturing with open-source 3-D printers. Mech. Tron. 2013, 23, 713–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, E.E.; Pearce, J. Emergence of Home Manufacturing in the Developed World: Return on Investment for Open-Source 3-D Printers. Technologies 2017, 5, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, I.; Bourell, D.; Gibson, I. Additive manufacturing: Rapid prototyping comes of age. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2012, 18, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, I.; Rosen, D.; Stucker, B. Additive Manufacturing Technologies: 3D Printing, Rapid Prototyping, and Direct Digital Manufacturing; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Kentzer, J.; Koch, B.; Thiim, M.; Jones, R.W.; Villumsen, E. An open source hardware-based mechatronics project: The replicating rapid 3-D printer. In Proceedings of the 4th International Conference on Mechatronics (ICOM), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 17–19 May 2011; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gwamuri, J.; Wittbrodt, B.T.; Anzalone, N.C.; Pearce, J.M. Reversing the trend of large scale and centralization in manufacturing: The case of distributed manufacturing of customizable 3-D-printable self-adjustable glasses. Chall. Sustain. 2014, 2, 30–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, J.L.; Oppliger, D.E.; Pearce, J.M.; Anzalone, G. Evaluation of RepRap 3D Printer Work-shops in K-12 STEM. In Proceedings of the 122nd ASEE Conference, Seattle, WA, USA, 14–17 June 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez-Gomez, J.; Valero-Gomez, A.; Prieto-Moreno, A.; Abderrahim, M. A New Open Source 3D-Printable Mobile Robotic Platform for Education. In Advances in Autonomous Mini Robots; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 49–62. [Google Scholar]

- Schelly, C.; Anzalone, G.; Wijnen, B.; Pearce, J.M. Open-source 3-D printing technologies for education: Bringing additive manufacturing to the classroom. J. Vis. Lang. Comput. 2015, 28, 226–237. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M.; Blair, C.M.; Laciak, K.J.; Andrews, R.; Nosrat, A.; Zelenika-Zovko, I. 3-D printing of open source appropriate technologies for self-directed sustainable development. J. Sustain. Dev. 2010, 3, 17–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, S. After the factory [Manufacturing renewal]. Eng. Technol. 2010, 5, 51–61. [Google Scholar]

- Pearce, J.M. Applications of open source 3-D printing on small farms. Organ. Farming 2015, 1, 19–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pearce, J.M. Building Research Equipment with Free, Open-Source Hardware. Science 2012, 337, 1301–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, J.M. Open-Source Lab: How to Build Your Own Hardware and Reduce Research Costs; Elsevier: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Baden, T.; Chagas, A.M.; Gage, G.J.; Marzullo, T.C.; Prieto-Godino, L.L.; Euler, T. Correction: Open labware: 3-D printing your own lab equipment. PLoS Biol. 2015, 13, e1002175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coakley, M.; Hurt, D.E. 3D Printing in the Laboratory. J. Lab. Autom. 2016, 21, 489–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- O’Neill, P.F.; Ben Azouz, A.; Vázquez, M.; Liu, J.; Marczak, S.; Slouka, Z.; Chang, H.C.; Diamond, D.; Brabazon, D. Advances in three-dimensional rapid prototyping of microfluidic devices for biological applications. Biomicrofluidics 2014, 8, 52112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pearce, J.M.; Anzalone, N.C.; Heldt, C.L. Open-Source Wax RepRap 3-D Printer for Rapid Prototyping Paper-Based Microfluidics. J. Lab. Autom. 2016, 21, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rimock, M. An Introduction to the Intellectual Property Law Implications of 3D Printing. Can. J. Law Technol. 2015, 13, 1–32. [Google Scholar]

- Laplume, A.; Anzalone, G.C.; Pearce, J.M. Open-source, self-replicating 3-D printer factory for small-business manufacturing. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 85, 633–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tech, R.P.G.; Ferdinand, J.-P.; Dopfer, M. Open Source Hardware Startups and Their Communities; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 129–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troxler, P.; van Woensel, C. How Will Society Adopt 3D Printing; T.M.C. Asser Press: Den Haag, The Netherlands, 2016; pp. 183–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleszczynski, S.; zur Jacobsmühlen, J.; Sehrt, J.T.; Witt, G. Error detection in laser beam melting systems by high resolution imaging. In Proceedings of the Solid Freeform Fabrication Symposium, Austin, TX, USA, 6–8 August 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Kleszczynski, S.; zur Jacobsmühlen, J.; Reinarz, B.; Sehrt, J.T.; Witt, G.; Merhof, D. Improving process stability of laser beam melting systems. In Proceedings of the Frauenhofer Direct Digital Manufacturing Conference, Berlin, Germany, 12–13 March 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Zur Jacobsmuhlen, J.; Kleszczynski, S.; Witt, G.; Merhof, D. Robustness analysis of imaging sys-tem for inspection of laser beam melting systems. In Proceedings of the 2014 IEEE Emerging Technology and Factory Automation (ETFA), Barcelona, Spain, 16–19 September 2014; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Concept Laser. Metal Additive Manufacturing Machines. 2016. Available online: http://www.conceptlaserinc.com/ (accessed on 10 November 2016).

- Faes, M.; Abbeloos, W.; Vogeler, F.; Valkenaers, H.; Coppens, K.; Goedemé, T.; Ferraris, E. Process Monitoring of Extrusion Based 3D Printing via Laser Scanning. Comput. Vis. Pattern Recognit. 2014, 6, 363–367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Volpato, N.; Aguiomar Foggiatto, J.; Coradini Schwarz, D. The influence of support base on FDM accuracy in Z. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2014, 20, 182–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Wang, Y.; Yu, Z. In situ monitoring of FDM machine condition via acoustic emission. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2016, 84, 1483–1495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atli, A.V.; Urhan, O.; Ertürk, S.; Sönmez, M. A computer vision-based fast approach to drilling tool condition monitoring. J. Eng. Manuf. 2006, 220, 1409–1415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradley, C.; Wong, Y.S. Surface texture indicators of tool wear—A machine vision approach. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2001, 17, 435–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bradski, G.; Kaehler, A. Learning OpenCV: Computer Vision with the OpenCV Library; O’Reilly Media, Inc.: Sebastopol, CA, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Edinbarough, I.; Balderas, R.; Bose, S. A vision and robot based on-line inspection monitoring system for electronic manufacturing. Comput. Ind. 2005, 56, 986–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golnabi, H.; Asadpour, A. Design and application of industrial machine vision systems. Robot. Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2007, 23, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, S.; Zhang, X.; Zhang, L.; Wan, Y.; Yuan, J.; Zhang, L. Application of computer vision in tool condition monitoring. J. Zhejiang Univ. Technol. 2002, 30, 143–148. [Google Scholar]

- Kerr, D.; Pengilley, J.; Garwood, R. Assessment and visualization of machine tool wear using computer vision. Int. J. Adv. Manuf. Technol. 2006, 28, 781–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klancnik, S.; Ficko, J.; Pahole, I. Computer Vision-Based Approach to End Mill Tool Monitoring. Int. J. Simul. Model. 2015, 14, 571–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzetta, M. A new flexible high-resolution vision sensor for tool condition monitoring. J. Mater. Process. Technol. 2001, 119, 73–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Li, Y.F.; Wang, Q.L.; Xu, D.; Tan, M. Measurement and defect detection of the weld bead based on online vision inspection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2010, 59, 1841–1849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, T.; Wiegers, L. Reliable tool wear monitoring by optimized image and illumination control in machine vision. Measurement 2000, 28, 209–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.H.; Hong, G.S.; Wong, Y.S.; Zhu, K.P. Sensor fusion for online tool condition monitoring in milling. Int. J. Prod. Res. 2007, 45, 5095–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurd, S.; Camp, C.; White, J. Quality Assurance in Additive Manufacturing through Mobile Computing; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 203–220. [Google Scholar]

- Baumann, F.; Roller, D. Vision based error detection for 3D printing processes. MATEC Web Conf. 2016, 59, 06003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straub, J. Initial work on the characterization of additive manufacturing (3D printing) using soft-ware image analysis. Machines 2015, 3, 55–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenCV. OpenCV library 2016. Available online: http://opencv.org/ (accessed on 10 November 2016).

- Python. Welcome to Python.org 2016. Available online: https://www.python.org/ (accessed on 10 November 2016).

- Raspberry, P. Teach, Learn, and Make with Raspberry Pi 2016. Available online: https://www.raspberrypi.org/ (accessed on 3 December 2016).

- Microsoft. Learn to Develop with Microsoft Developer Network|MSDN 2016. Available online: https://msdn.microsoft.com/en-us/default.aspx (accessed on 13 November 2016).

- Gewirtz, D. Adding a Raspberry Pi case and a camera to your LulzBot Mini—Watch Video Online—Watch Latest Ultra HD 4K Videos Online 2016. Available online: http://www.zdnet.com/article/3d-printing-hands-on-adding-a-case-and-a-camera-to-the-raspberry-pi-and-lulzbot-mini/ (accessed on 30 November 2016).

- Printer3D. Free IP Camera Monitoring for 3D printer with old webcam usb in 5min—3D Printers English French & FAQ Wanhao Duplicator D6 Monoprice Maker Ultimate & D4, D5, Duplicator 7. 2017. Available online: http://www.printer3d.one/en/forums/topic/free-ip-camera-monitoring-for-3d-printer-with-old-webcam-usb-in-5min/ (accessed on 18 March 2017).

- Carmelito. Controlling and Monitoring your 3D printer with...|element14|MusicTech 2016. Available online: https://www.element14.com/community/community/design-challenges/musictech/blog/2016/03/16/controlling-your-3d-printer-with-beaglebone-and-octoprint (accessed on 18 March 2017).

- Simon, J. Monitoring Your 3D Prints|3D Universe 2017. Available online: https://3duniverse.org/2014/01/06/monitoring-your-3d-prints/ (accessed on 18 March 2017).

- Ken, V. Logitech C170 webcam mount for daVinci 3D Printer by KenVersus—Thingiverse. 2015. Available online: http://www.thingiverse.com/thing:747105 (accessed on 18 March 2017).

- Lowe, D.G. Object recognition from local scale-invariant features. In Proceedings of the Seventh IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Washington, DC, USA, 20–25 September 1999; Volume 2, pp. 1150–1157. [Google Scholar]

- Fischler, M.A.; Bolles, R.C. Random sample consensus: A paradigm for model fitting with applications to image analysis and automated cartography. Commun. ACM 1981, 24, 381–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nuchitprasitchai, S.; Roggemann, M.C.; Havens, T.C. Algorithm for Reconstructing Three Dimensional Images from Overlapping Two Dimensional Intensity Measurements with Relaxed Camera Positioning Requirements to reconstruct 3D image. IJMER 2016, 6, 69–81. [Google Scholar]

- Anzalone, G.C.; Wijnen, B.; Pearce, J.M. Multi-material additive and subtractive prosumer digital fabrication with a free and open-source convertible delta RepRap 3-D printer. Rapid Prototyp. J. 2015, 21, 506–519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzalone, G.; Wijnen, B.; Pearce, J.M. Delta Build Overview: MOST—Appropedia: The sustainability wiki 2016. Available online: http://www.appropedia.org/Delta_Build_Overview:MOST (accessed on 13 June 2016).

- Rostock. RepRapWiki 2016. Available online: http://reprap.org/wiki/Rostock (accessed on 5 November 2016).

- Nuchitprasitchai, S.; Roggemann, M.; Pearce, J. Factors Effecting Real Time Optical Monitoring of Fused Filament 3-D Printing. Prog. Addit. Manuf. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OpenCV. Camera Calibration and 3D Reconstruction—OpenCV 2.4.13.2 documentation. 2016. Available online: http://docs.opencv.org/2.4/modules/calib3d/doc/camera_calibration_and_3d_reconstruction.html#stereobm (accessed on 3 December 2016).

- Dollar Tree, Inc. Floral Supplies, Party Supplies, Cleaning Supplies. 2016. Available online: https://www.dollartree.com/ (accessed on 3 December 2016).

- Thing-O-Fun. Exploded Planetary Gear Set by Thing-O-Fun—Thingiverse. 2012. Available online: http://www.thingiverse.com/thing:18291 (accessed on 3 December 2016).

- Jetty. Paper Crimper by jetty—Thingiverse. 2012. Available online: http://www.thingiverse.com/thing:17634 (accessed on 3 December 2016).

- Droffarts. Parametric pulley—lots of tooth profiles by droftarts—Thingiverse. Available online: http://www.thingiverse.com/thing:16627 (accessed on 12 March 2017).

- Nuchitprasitchai, S. 3-D models. 2017. Available online: https://osf.io/utp6g/ (accessed on 5 April 2017).

- Wijnen, B.; Anzalone, G.C.; Haselhuhn, A.S.; Sanders, P.G.; Pearce, J.M. Free and open-source control software for 3-D motion and processing. J. Open Res. Softw. 2016, 4, e2. [Google Scholar]

- MathWorks. Pricing and Licensing—MATLAB & Simulink. 2016. Available online: https://www.mathworks.com/pricing-licensing.html?intendeduse=comm (accessed on 8 December 2016).

- Nuchitprasitchai, S. Rod alarm—Appropedia: The sustainability wiki. 2016. Available online: http://www.appropedia.org/Rod_alarm (accessed on 20 March 2017).

- Barker, B. Thrown Rod Halt Mod—Appropedia: The sustainability wiki. Available online: http://www.appropedia.org/Thrown_Rod_Halt_Mod (accessed on 20 March 2017).

- Mahan, T. Raspberry Pi Control and Wireless Interface—Appropedia: The sustainability wiki. 2016. Available online: http://www.appropedia.org/Raspberry_Pi_Control_and_Wireless_Interface (accessed on 20 March 2017).

- Nuchitprasitchai, S.; Roggemann, M.; Pearce, J. An Open Source Algorithm for Reconstruction 3-D images for Low-cost, Reliable Real-time Monitoring of FFF-based 3-D Printing. 2017; submitted. [Google Scholar]

- Abidrahmank. OpenCV2-Python-Tutorials. 2014. Available online: https://github.com/abidrahmank/OpenCV2-Python-Tutorials/ (accessed on 30 March 2017).

© 2017 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Nuchitprasitchai, S.; Roggemann, M.C.; Pearce, J.M. Three Hundred and Sixty Degree Real-Time Monitoring of 3-D Printing Using Computer Analysis of Two Camera Views. J. Manuf. Mater. Process. 2017, 1, 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp1010002

Nuchitprasitchai S, Roggemann MC, Pearce JM. Three Hundred and Sixty Degree Real-Time Monitoring of 3-D Printing Using Computer Analysis of Two Camera Views. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing. 2017; 1(1):2. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp1010002

Chicago/Turabian StyleNuchitprasitchai, Siranee, Michael C. Roggemann, and Joshua M. Pearce. 2017. "Three Hundred and Sixty Degree Real-Time Monitoring of 3-D Printing Using Computer Analysis of Two Camera Views" Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing 1, no. 1: 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp1010002

APA StyleNuchitprasitchai, S., Roggemann, M. C., & Pearce, J. M. (2017). Three Hundred and Sixty Degree Real-Time Monitoring of 3-D Printing Using Computer Analysis of Two Camera Views. Journal of Manufacturing and Materials Processing, 1(1), 2. https://doi.org/10.3390/jmmp1010002