Long COVID Neuropsychological Deficits after Severe, Moderate, or Mild Infection

Abstract

:1. Introduction

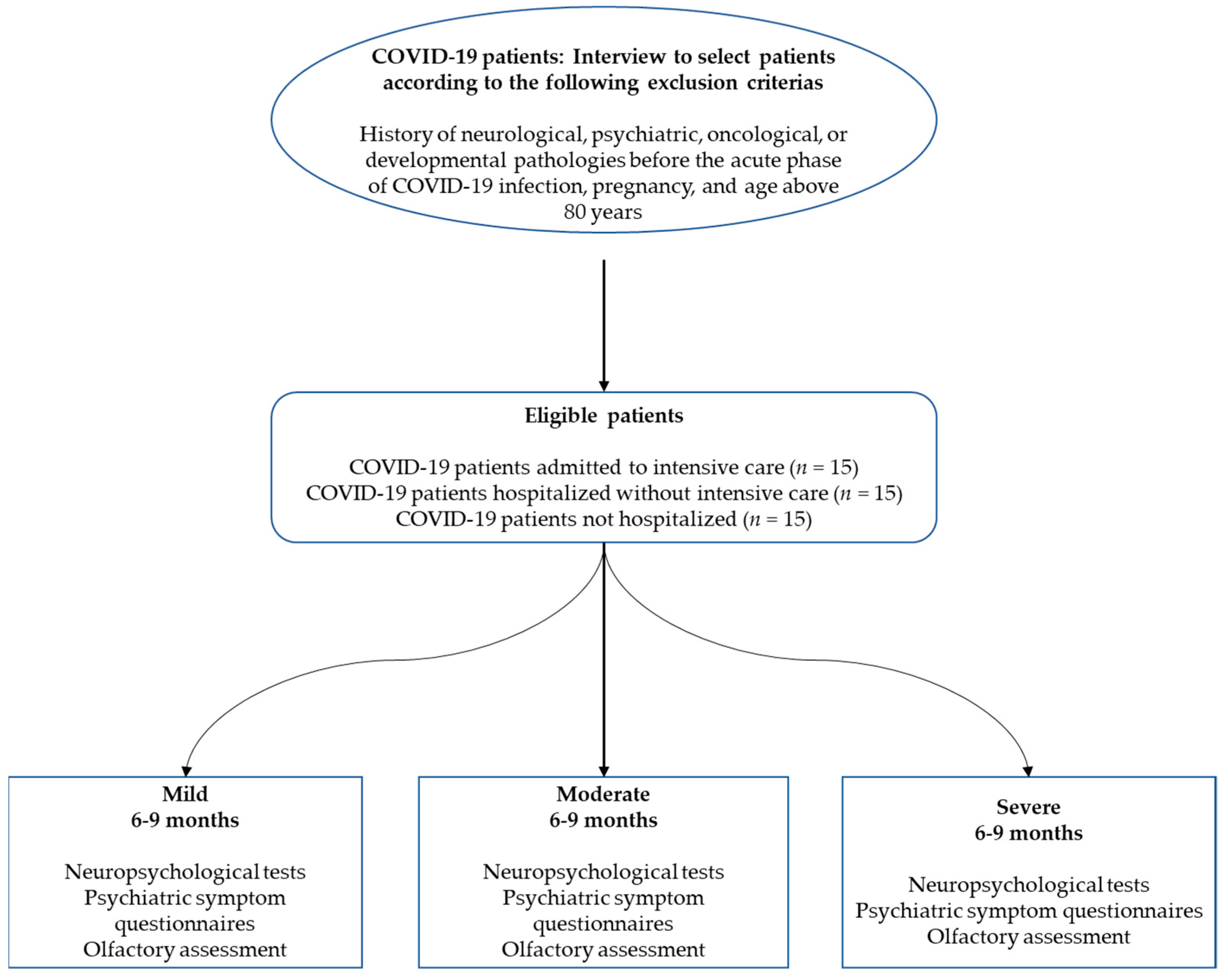

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants

2.2. General Procedure and Ethics

2.3. Neuropsychological Assessment

2.4. Other Clinical Outcomes

2.5. Statistical Analyses

2.5.1. Prevalence of Neuropsychological Deficits and Psychiatric Symptoms (Objective 1)

2.5.2. Neuropsychological Deficits as a Function of Disease Severity (Objective 2)

2.5.3. Relationships between Neuropsychological Deficits, Psychiatric Symptoms, and Other Secondary Variables (Objective 3)

3. Results

3.1. Neuropsychological, Psychiatric, and Olfactory Profiles 6–9 Months Post-Infection

| Mild (No Hospitalization) n = 15 | Moderate (Conventional Hospitalization) n = 15 | Severe (ICU Hospitalization) n = 15 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Function | Prevalence under P5 (mean%) | Prevalence under P16 (mean%) | Prevalence under P5 (mean%) | Prevalence under P16 (mean%) | Prevalence under P5 (mean%) | Prevalence under P16 (mean%) |

| Memory | ||||||

| Verbal episodic memory (/5) | 1.34 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 13.26 | 8.00 | 17.33 |

| Visuospatial episodic memory (/4) | 1.67 | 3.34 | 15.00 | 20.00 | 1.67 | 5.00 |

| Verbal short-term memory (/1) | 0.00 | 6.67 | 6.67 | 33.33 | 6.67 | 6.67 |

| Visuospatial short-term memory (/1) | 0.00 | 6.67 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Executive functions | ||||||

| Inhibition (/3) | 15.56 | 22.22 | 11.90 | 23.81 | 13.33 | 28.89 |

| Verbal Working memory (/1) | 6.67 | 6.67 | 0.00 | 13.33 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| Visuospatial working memory (/3) | 6.67 | 13.34 | 4.45 | 11.11 | 6.82 | 13.33 |

| Mental flexibility (/6) | 3.33 | 7.78 | 14.44 | 18.89 | 11.11 | 18.89 |

| Verbal fluency (/2) | 6.67 | 26.67 | 13.33 | 53.33 | 6.67 | 26.67 |

| Incompatibility (/4) | 0.00 | 13.33 | 5.00 | 21.67 | 6.67 | 10.00 |

| Interhemispheric transfer (/2) | 10.00 | 20.00 | 6.67 | 30.00 | 6.67 | 26.67 |

| Attentional functions | ||||||

| Phasic alertness (/5) | 10.67 | 18.67 | 0.00 | 20.00 | 1.33 | 14.67 |

| Sustained attention (/2) | 10.00 | 16.67 | 26.93 | 34.62 | 7.69 | 11.54 |

| Divided attention (/4) | 8.34 | 21.67 | 6.67 | 16.67 | 8.33 | 21.67 |

| Instrumental functions | ||||||

| Language (/5) | 4.00 | 9.34 | 5.33 | 8.00 | 6.67 | 16.00 |

| Ideomotor praxis (/3) | 4.44 | - | 0.00 | - | 2.22 | - |

| Object perception (/2) | 10.00 | - | 20.00 | - | 0.00 | - |

| Spatial perception (/2) | 0.00 | - | 13.33 | - | 3.33 | - |

| Logical reasoning (/2) | 3.33 | 10.00 | 10.00 | 13.33 | 0.00 | 6.67 |

| Anosognosia for memory | 0.00 | - | 40.00 | - | 40.00 | - |

| Anosognosia-Executive functions-Inhibition | 20.00 | - | 26.67 | - | 53.33 | - |

| Anosognosia-Executive functions-Flexibility | 20.00 | - | 33.33 | - | 33.33 | - |

| Anosognosia-Executive functions-Working memory | 6.67 | - | 6.67 | - | 0.00 | - |

| Cognitive complaints | 6.67 | - | 13.33 | - | 0 | - |

| Psychiatric Symptoms | Mild (No Hospitalization) n = 15 | Moderate (Conventional Hospitalization) n = 15 | Severe (ICU Hospitalization) n = 15 | Kruskal–Wallis p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Depression (BDI-II) (prevalence) | Minor = 46.67% | Minor = 66.67% | Minor = 80% | 0.009 |

| Mild = 20% | Mild = 20% | Mild = 20% | ||

| Moderate = 33.33% | Moderate = 13.33% | Moderate = 0% | ||

| Severe = 0% | Severe = 0% | Severe = 0% | ||

| State anxiety (STAI-state) (prevalence) | Very low = 26.67% | Very low = 60% | Very low = 86.67% | 0.002 |

| Low = 33.33% | Low = 6.67% | Low = 6.67% | ||

| Moderate = 13.33% | Moderate = 20% | Moderate = 6.67% | ||

| High = 26.67% | High = 13.33% | High = 0% | ||

| Very high = 0% | Very high = 0% | Very high = 0% | ||

| Trait anxiety (STAI-trait) (prevalence) | Very low = 46.67% | Very low = 73.33% | Very low = 60% | 0.100 |

| Low = 26.67% | Low = 0% | Low = 33.33% | ||

| Moderate = 13.33% | Moderate = 20% | Moderate = 6.67% | ||

| High = 13.33% | High = 6.67% | High = 0% | ||

| Very high = 0% | Very high = 0% | Very high = 0% | ||

| Mania (Goldberg Inventory) (prevalence) | Probably absent = 26.67% | Probably absent = 13.33% | Probably absent = 20% | 0.909 |

| Hypomania = 26.67% | Hypomania = 26.67% | Hypomania = 46.67% | ||

| Close to mania = 20% | Close to mania = 20% | Close to mania = 6.67% | ||

| Moderate = 26.67% | Moderate = 40% | Moderate = 26.67% | ||

| Ordinary to severe = 0% | Ordinary to severe = 0% | Ordinary to severe = 0% | ||

| Severe = 0% | Severe = 0% | Severe = 0% | ||

| Apathy (AMI-total) (prevalence) | Absent = 86.67% | Absent = 93.33% | Absent = 73.33% | 0.602 |

| Moderate = 13.33% | Moderate = 6.67% | Moderate = 26.67% | ||

| High = 0% | High = 0% | High = 0% | ||

| Behavioral apathy (AMI-behavioral) (prevalence) | Absent = 100% | Absent = 100% | Absent = 93.33% | 0.211 |

| Moderate = 0% | Moderate = 0% | Moderate = 6.67% | ||

| High = 0% | High = 0% | High = 0% | ||

| Social apathy (AMI-social) (prevalence) | Absent = 93.33% | Absent = 86.67% | Absent = 73.33% | 0.940 |

| Moderate = 6.67% | Moderate = 6.67% | Moderate = 26.67% | ||

| High = 0% | High = 6.67% | High = 0% | ||

| Emotional apathy (AMI-emotional) (prevalence) | Absent = 73.33% | Absent = 60% | Absent = 40% | 0.029 |

| Moderate = 26.67% | Moderate = 40% | Moderate = 33.33% | ||

| High = 0% | High = 0% | High = 26.67% | ||

| Posttraumatic stress disorder (PCL-5) (prevalence) | Absent = 86.67% | Absent = 86.67% | Absent = 93.33% | 0.054 |

| Present = 13.33% | Present = 13.33% | Present = 6.67% | ||

| Stress (PSS-14) Mean (±SD) | 26.13 (±9.53) | 19.6 (±7.47) | 14.93 (±9.42) | 0.023 |

| Dissociative disorder (DES) Mean (±SD) | 7.68 (±11.89) | 10.45 (±9.23) | 3.98 (±3.03) | 0.140 |

| Emotional contagion (ECS) Mean (±SD) | 41.40 (±7.20) | 44.6 (±4.22) | 36.13 (±8.38) | 0.002 |

| Emotion regulation (ERQ) Mean (±SD) | 41.6 (±7.39) | 44.2 (±8.33) | 39.80 (±11.77) | 0.416 |

| Somnolence (Epworth) (prevalence) | Pathological = 40.00% | Pathological = 53.33% | Pathological = 26.67% | 0.036 |

| Insomnia (ISI) (prevalence) | Absent = 20% | Absent = 46.67% | Absent = 60% | 0.040 |

| Mild = 40% | Mild = 40% | Mild = 26.67% | ||

| Moderate = 40% | Moderate = 13.33% | Moderate = 13.33% | ||

| Severe = 0% | Severe = 0% | Severe = 0% | ||

| Fatigue (EMIF-SEP) (prevalence) | Present = 13.33% | Present = 20% | Present = 6.67% | 0.088 |

| Sniff test (anosmia) Mean (±SD) | 13.07 (±1.44) | 11.53 (±2.13) | 11.47 (±2.90) | 0.067 |

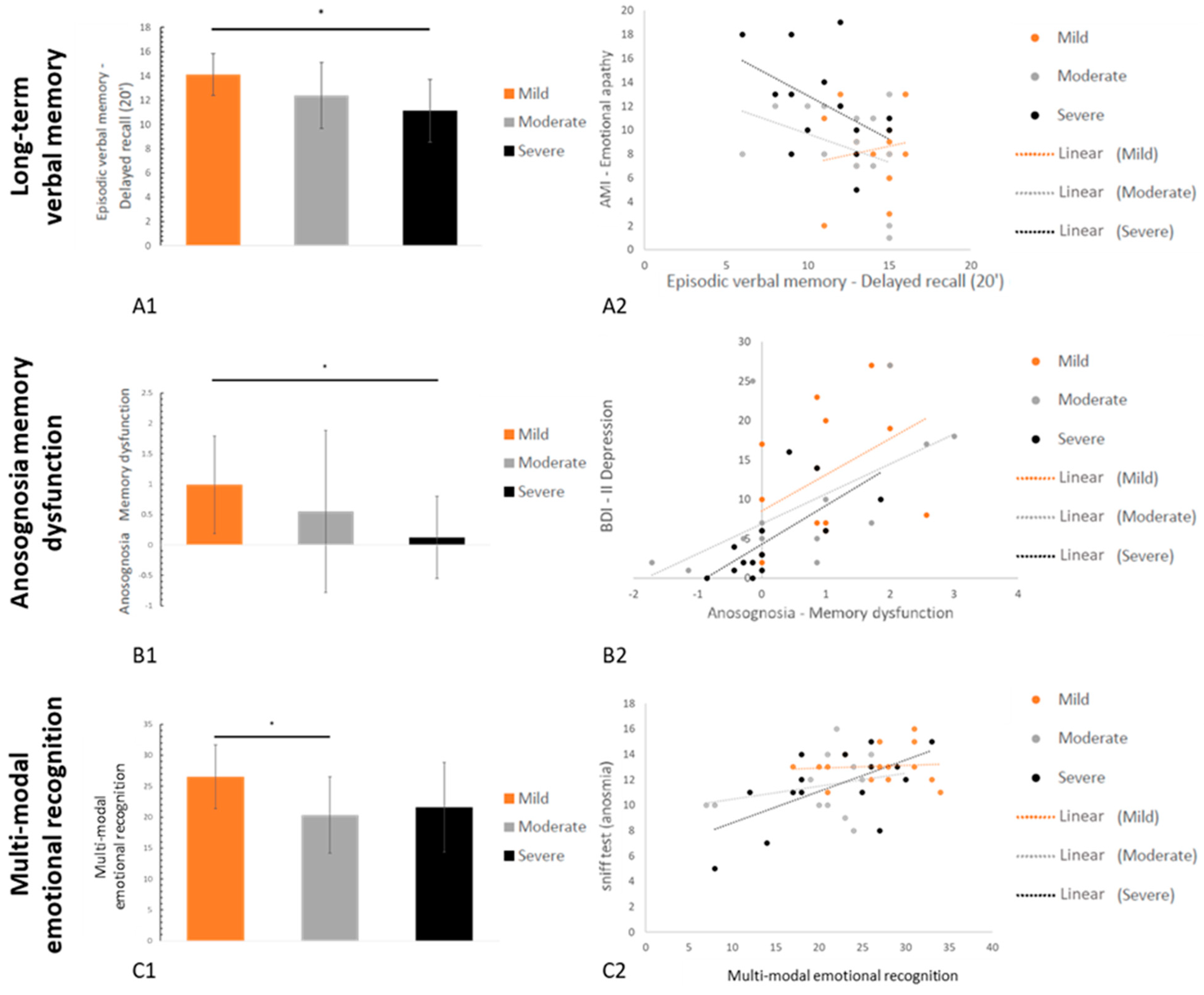

3.2. Neuropsychological and Psychiatric Symptoms as a Function of Disease Severity

3.2.1. Neuropsychological Data

3.2.2. Psychiatric Data

3.2.3. Fatigue and Quality of Life

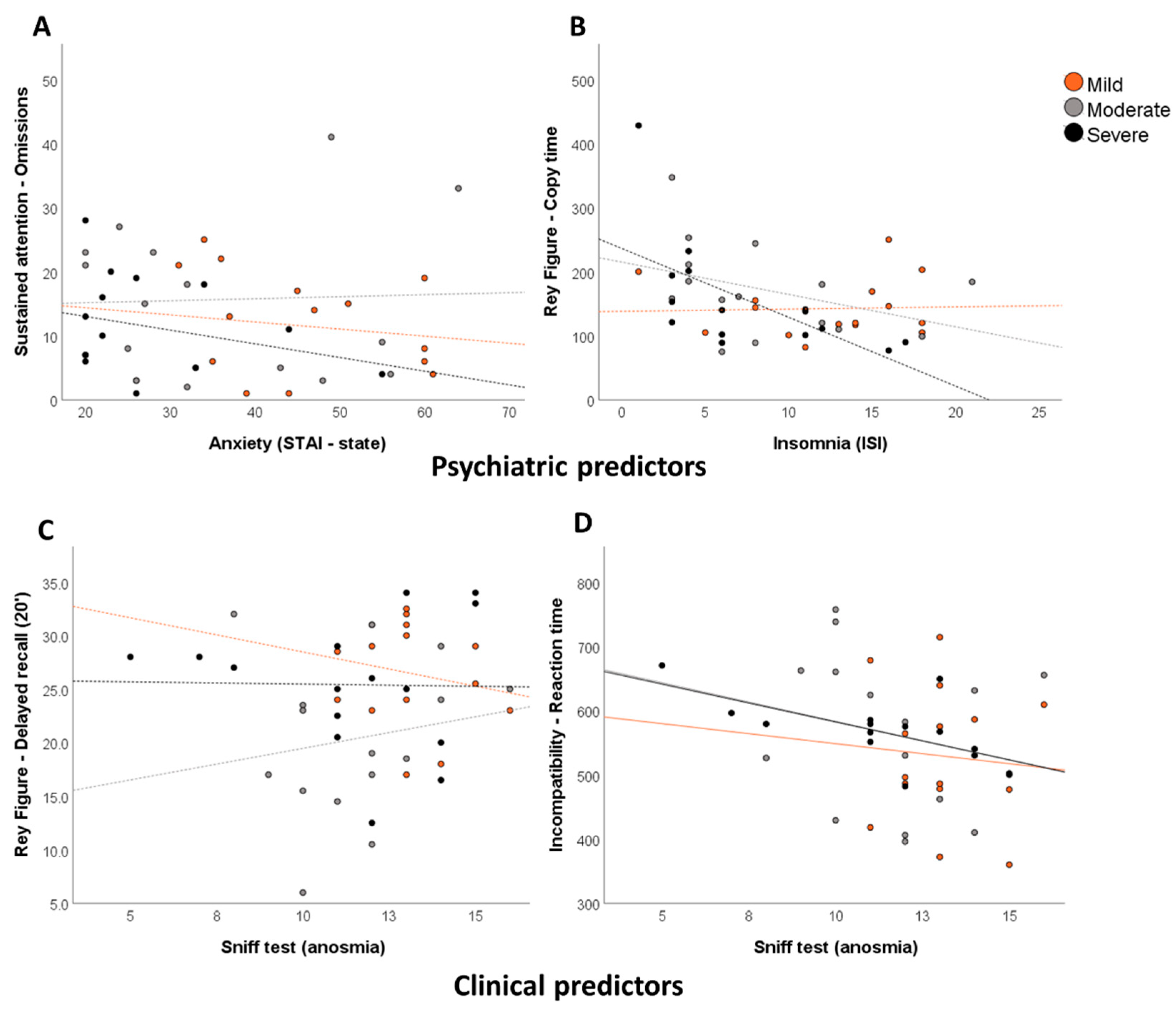

3.3. Relationships between Neuropsychological Deficits, Psychiatric Symptoms, and Other Secondary Variables

| Regressor | R2 | p Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Memory Functions | ||||

| Verbal episodic memory | Grober & Buschke (RL/RI 16)-Immediate recall | ns | ns | ns |

| Grober & Buschke (RL/RI 16)-Delayed free recall | AMI–Emotional apathy | 0.45 | 0.006 | |

| Epworth-Sleepiness | 0.20 | 0.022 | ||

| ERQ–Emotion regulation | 0.13 | 0.034 | ||

| ECS–Emotional contagion | 0.08 | 0.034 | ||

| Grober & Buschke (RL/RI 16)-Delayed total recall | AMI–Emotional apathy | 0.34 | 0.022 | |

| Epworth-Sleepiness | 0.22 | 0.031 | ||

| AMI–Social apathy | 0.15 | 0.034 | ||

| Visuospatial episodic memory | Rey Figure-Copy time | ISI-Insomnia | 0.46 | 0.005 |

| ERQ–Emotion regulation | 0.18 | 0.035 | ||

| Rey Figure-Score | ns | ns | ns | |

| Rey Figure-Immediate recall (3’) | ns | ns | ns | |

| Rey Figure-Delayed recall (20’) | ISI–Insomnia | 0.30 | 0.034 | |

| Days of hospitalization | 0.22 | 0.039 | ||

| Sniff test (anosmia) | 0.21 | 0.013 | ||

| Verbal short-term memory | MEM III-Spans | ns | ns | ns |

| Visuospatial short-term memory | WAIS IV-Spans | DES–Dissociation | 0.30 | 0.035 |

| Executive functions | ||||

| Inhibition | Stroop (GREFEX)-Interference-Time | ns | ns | ns |

| Stroop (GREFEX)-Interference-Errors | AMI–Total apathy | 0.37 | 0.015 | |

| ERQ–Emotion regulation | 0.21 | 0.030 | ||

| Stroop (GREFEX)-Interference/Naming-Score | ns | ns | ns | |

| Working memory | MEM III–Verbal working memory | AMI–Behavioral apathy | 0.33 | 0.026 |

| WAIS IV-Visuospatial working memory | STAI-T Anxiety | 0.39 | 0.013 | |

| Diabetes | 0.25 | 0.014 | ||

| STAI-S Anxiety | 0.13 | 0.03 | ||

| TAP-Working memory item omissions | AMI–Emotional apathy | 0.30 | 0.035 | |

| TAP-Working memory false alarms | Diabetes | 0.47 | 0.005 | |

| Mania–Goldberg Inventory | 0.16 | 0.044 | ||

| Mental flexibility | TMT A (GREFEX)-Time | ns | ns | ns |

| TMT A (GREFEX)-Errors | ns | ns | ns | |

| TMT B (GREFEX)-Time | ns | ns | ns | |

| TMT B (GREFEX)-Errors | AMI–Total apathy | 0.41 | 0.010 | |

| ERQ–Emotion regulation | 0.14 | 0.024 | ||

| Gender | 0.13 | 0.025 | ||

| TMT B (GREFEX)-Perseverations | STAI-T Anxiety | 0.55 | 0.002 | |

| BDI-II-Depression | 0.16 | 0.026 | ||

| ISI–Insomnia | 0.20 | <0.001 | ||

| TMT B-A (GREFEX)-Score | ns | ns | ns | |

| Verbal fluency (GREFEX)-Literal (2’) | ns | ns | ns | |

| Verbal fluency (GREFEX)-Categorical fluency (2’) | DES–Dissociation | 0.28 | 0.047 | |

| Incompatibility | TAP-Compatibility-Reaction time | AMI–Social apathy | 0.50 | 0.003 |

| TAP-Compatibility-False alarms | ns | ns | ns | |

| TAP-Incompatibility-Reaction Time | Sniff test (anosmia) | 0.28 | 0.043 | |

| DES–Dissociation | 0.25 | 0.026 | ||

| ERQ–Emotion regulation | 0.13 | 0.028 | ||

| Epworth-Sleepiness | 0.10 | 0.017 | ||

| TAP-Incompatibility-False alarms | Sniff test (anosmia) | 0.27 | 0.045 | |

| TAP-Incompatibility-Visual field score | Days of hospitalization | 0.39 | 0.013 | |

| Diabetes | 0.23 | 0.007 | ||

| STAI-T Anxiety | 0.08 | 0.041 | ||

| PCL-5 Posttraumatic stress disorder | 0.06 | 0.041 | ||

| TAP-Incompatibility task-Hands score | AMI–Social apathy | 0.44 | 0.008 | |

| TAP-Incompatibility task-Visual fields * Hands score | ISI–Insomnia | 0.33 | 0.025 | |

| STAI-T Anxiety | 0.24 | 0.025 | ||

| BDI-II-Depression | 0.18 | 0.019 | ||

| Attentional functions | ||||

| Phasic alertness | TAP-Without warning sound-Reaction time | Gender | 0.35 | 0.019 |

| TAP-Without warning sound-SD of reaction time | AMI–Social apathy | 0.64 | <0.001 | |

| Diabetes | 0.11 | 0.041 | ||

| Sniff test (anosmia) | 0.10 | 0.023 | ||

| TAP-With warning sound-Reaction time | DES–Dissociation | 0.30 | 0.033 | |

| TAP-With warning sound-SD of reaction time | ns | ns | ns | |

| TAP-Alertness index | Gender | 0.28 | 0.041 | |

| Sustained attention | TAP-Items Omissions | STAI-Trait Anxiety | 0.46 | 0.005 |

| TAP-False alarm | ns | ns | ns | |

| Divided attention | TAP-Audio condition-Reaction time | DES–Dissociation | 0.41 | 0.010 |

| AMI–Behavioral apathy | 0.27 | 0.008 | ||

| TAP-Visual condition-Reaction time | Days of hospitalization | 0.38 | 0.014 | |

| Sniff test (anosmia) | 0.27 | 0.009 | ||

| ISI-Insomnia | 0.23 | <0.001 | ||

| AMI–Emotional apathy | 0.05 | 0.016 | ||

| TAP-Total omissions | ns | ns | ns | |

| TAP-Total false alarms | AMI–Emotional apathy | 0.32 | 0.029 | |

| Epworth-Sleepiness | 0.28 | 0.015 | ||

| AMI–Social apathy | 0.16 | 0.023 | ||

| Instrumental functions | ||||

| Language | BECLA-Semantic image matching | ns | ns | ns |

| BECLA-Semantic word matching | ns | ns | ns | |

| BECLA-Object and action image naming | ECS–Emotional contagion | 0.38 | 0.014 | |

| STAI-State Anxiety | 0.29 | 0.007 | ||

| AMI–Emotional apathy | 0.10 | 0.014 | ||

| ISI-Insomnia | 0.08 | 0.012 | ||

| BECLA-Word repetition | NV | NV | NV | |

| BECLA-Nonword repetition | ns | ns | ns | |

| Ideomotor praxis | Symbolic gestures | ERQ–Emotion regulation | 0.35 | 0.019 |

| AMI–Behavioral apathy | 0.33 | 0.004 | ||

| Action pantomimes | BDI-II-Depression | 0.51 | 0.003 | |

| Meaningless gestures | AMI–Total apathy | 0.30 | 0.033 | |

| AMI–Social apathy | 0.18 | 0.035 | ||

| Object perception | VOSP-Fragmented letters | AMI–Total apathy | 0.26 | 0.029 |

| VOSP-Object decision | ns | ns | ns | |

| Spatial perception | VOSP-Number localization | ns | ns | ns |

| VOSP-Cubic counting | Mania–Goldberg Inventory | 0.27 | 0.047 | |

| PSS-14-Stress | 0.24 | 0.034 | ||

| Logical reasoning | WAIS IV-Puzzle | Diabetes | 0.34 | 0.021 |

| WAIS IV-Matrix | DES–Dissociation | 0.28 | 0.041 | |

| Gender | 0.40 | 0.002 | ||

| Emotion recognition | GERT | ERQ–Emotion regulation | 0.33 | 0.023 |

| AMI–Emotional apathy | 0.28 | 0.011 | ||

| AMI–Behavioral apathy | 0.16 | 0.004 | ||

| Sniff test (anosmia) | 0.06 | 0.008 | ||

| AMI–Social apathy | 0.02 | 0.027 | ||

| Anosognosia | Memory dysfunctions | BDI-II-Depression | 0.62 | <0.001 |

| ISI-Insomnia | 0.12 | 0.038 | ||

| AMI–Behavioral apathy | 0.09 | 0.040 | ||

| Epworth-Sleepiness | 0.05 | 0.033 | ||

| Executive functions-Inhibition | AMI–Total apathy | 0.40 | 0.011 | |

| Executive functions-Flexibility | AMI–Behavioral score | 0.28 | 0.043 | |

| Executive functions–Working memory | Epworth-Sleepiness | 0.38 | 0.015 | |

| Sniff test (anosmia) | 0.25 | 0.015 | ||

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Rogers, J.P.; Chesney, E.; Oliver, D.; Pollak, T.A.; McGuire, P.; Fusar-Poli, P.; Zandi, M.S.; Lewis, G.; David, A.S. Psychiatric and neuropsychiatric presentations associated with severe coronavirus infections: A systematic review and meta-analysis with comparison to the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 611–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mao, L.; Jin, H.; Wang, M.; Hu, Y.; Chen, S.; He, Q.; Chang, J.; Hong, C.; Zhou, Y.; Wang, D. Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 683–690. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Wendelken, L.A.; Valcour, V. Impact of HIV and aging on neuropsychological function. J. Neurovirol. 2012, 18, 256–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Piras, M.R.; Magnano, I.; Canu, E.D.G.; Paulus, K.S.; Satta, W.M.; Soddu, A.; Conti, M.; Achene, A.; Solinas, G.; Aiello, I. Longitudinal study of cognitive dysfunction in multiple sclerosis: Neuropsychological, neuroradiological, and neurophysiological findings. J. Neurol. Neurosurg. Psychiatry 2003, 74, 878–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- van Sonderen, A.; Thijs, R.D.; Coenders, E.C.; Jiskoot, L.C.; Sanchez, E.; De Bruijn, M.A.; van Coevorden-Hameete, M.H.; Wirtz, P.W.; Schreurs, M.W.; Smitt, P.A.S. Anti-LGI1 encephalitis: Clinical syndrome and long-term follow-up. Neurology 2016, 87, 1449–1456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merkler, A.E.; Parikh, N.S.; Mir, S.; Gupta, A.; Kamel, H.; Lin, E.; Lantos, J.; Schenck, E.J.; Goyal, P.; Bruce, S.S. Risk of ischemic stroke in patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) vs patients with influenza. JAMA Neurol. 2020, 77, 1366–1372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nannoni, S.; de Groot, R.; Bell, S.; Markus, H.S. Stroke in COVID-19: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int. J. Stroke 2020, 16, 137–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oxley, T.J.; Mocco, J.; Majidi, S.; Kellner, C.P.; Shoirah, H.; Singh, I.P.; De Leacy, R.A.; Shigematsu, T.; Ladner, T.R.; Yaeger, K.A. Large-vessel stroke as a presenting feature of COVID-19 in the young. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, e60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Maria, A.; Varese, P.; Dentone, C.; Barisione, E.; Bassetti, M. High prevalence of olfactory and taste disorder during SARS-CoV-2 infection in outpatients. J. Med. Virol. 2020, 92, 2310–2311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, J.-M.; Lee, S.J. Olfactory and gustatory dysfunction in a COVID-19 patient with ankylosing spondylitis treated with etanercept: Case report. J. Korean Med. Sci. 2020, 35, e201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brann, D.H.; Tsukahara, T.; Weinreb, C.; Lipovsek, M.; Van den Berge, K.; Gong, B.; Chance, R.; Macaulay, I.C.; Chou, H.-J.; Fletcher, R.B. Non-neuronal expression of SARS-CoV-2 entry genes in the olfactory system suggests mechanisms underlying COVID-19-associated anosmia. Sci. Adv. 2020, 6, eabc5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fodoulian, L.; Tuberosa, J.; Rossier, D.; Boillat, M.; Kan, C.; Pauli, V.; Egervari, K.; Lobrinus, J.A.; Landis, B.N.; Carleton, A. SARS-CoV-2 receptors and entry genes are expressed in the human olfactory neuroepithelium and brain. Iscience 2020, 23, 101839. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Butowt, R.; Bilinska, K. SARS-CoV-2: Olfaction, brain infection, and the urgent need for clinical samples allowing earlier virus detection. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 1200–1203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Vaira, L.A.; Hopkins, C.; Sandison, A.; Manca, A.; Machouchas, N.; Turilli, D.; Lechien, J.; Barillari, M.; Salzano, G.; Cossu, A. Olfactory epithelium histopathological findings in long-term coronavirus disease 2019 related anosmia. J. Laryngol. Otol. 2020, 134, 1123–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Doty, R.L. The olfactory vector hypothesis of neurodegenerative disease: Is it viable? Ann. Neurol. Off. J. Am. Neurol. Assoc. Child Neurol. Soc. 2008, 63, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Landis, B.N.; Vodicka, J.; Hummel, T. Olfactory dysfunction following herpetic meningoencephalitis. J. Neurol. 2010, 257, 439–443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kandemirli, S.G.; Altundag, A.; Yildirim, D.; Sanli, D.E.T.; Saatci, O. Olfactory Bulb MRI and paranasal sinus CT findings in persistent COVID-19 anosmia. Acad. Radiol. 2021, 28, 28–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meinhardt, J.; Radke, J.; Dittmayer, C.; Franz, J.; Thomas, C.; Mothes, R.; Laue, M.; Schneider, J.; Brünink, S.; Greuel, S. Olfactory transmucosal SARS-CoV-2 invasion as a port of central nervous system entry in individuals with COVID-19. Nat. Neurosci. 2021, 24, 168–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedj, E.; Million, M.; Dudouet, P.; Tissot-Dupont, H.; Bregeon, F.; Cammilleri, S.; Raoult, D. 18F-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in post-SARS-CoV-2 infection: Substrate for persistent/delayed disorders? Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2020, 48, 592–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guedj, E.; Campion, J.; Dudouet, P.; Kaphan, E.; Bregeon, F.; Tissot-Dupont, H.; Guis, S.; Barthelemy, F.; Habert, P.; Ceccaldi, M. 18F-FDG brain PET hypometabolism in patients with long COVID. Eur. J. Nucl. Med. Mol. Imaging 2021, 48, 2823–2833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almeria, M.; Cejudo, J.; Sotoca, J.; Deus, J.; Krupinski, J. Cognitive profile following COVID-19 infection: Clinical predictors leading to neuropsychological impairment. Brain Behav. Immun.-Health 2020, 9, 100163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jaywant, A.; Vanderlind, W.M.; Alexopoulos, G.S.; Fridman, C.B.; Perlis, R.H.; Gunning, F.M. Frequency and profile of objective cognitive deficits in hospitalized patients recovering from COVID-19. Neuropsychopharmacology 2021, 46, 2235–2240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hampshire, A.; Trender, W.; Chamberlain, S.R.; Jolly, A.E.; Grant, J.E.; Patrick, F.; Mazibuko, N.; Williams, S.C.R.; Barnby, J.M.; Hellyer, P.; et al. Cognitive deficits in people who have recovered from COVID-19. EClinicalMedicine 2021, 39, 101044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.; Lu, S.; Chen, J.; Wei, N.; Wang, D.; Lyu, H.; Shi, C.; Hu, S. The landscape of cognitive function in recovered COVID-19 patients. J. Psychiatr. Res. 2020, 129, 98–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Woo, M.S.; Malsy, J.; Pöttgen, J.; Seddiq Zai, S.; Ufer, F.; Hadjilaou, A.; Schmiedel, S.; Addo, M.M.; Gerloff, C.; Heesen, C. Frequent neurocognitive deficits after recovery from mild COVID-19. Brain Commun. 2020, 2, fcaa205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bäuerle, A.; Teufel, M.; Musche, V.; Weismüller, B.; Kohler, H.; Hetkamp, M.; Dörrie, N.; Schweda, A.; Skoda, E.-M. Increased generalized anxiety, depression and distress during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study in Germany. J. Public Health 2020, 42, 672–678. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Röhr, S.; Müller, F.; Jung, F.; Apfelbacher, C.; Seidler, A.; Riedel-Heller, S.G. Psychosocial impact of quarantine measures during serious coronavirus outbreaks: A rapid review. Psychiatr. Prax. 2020, 47, 179–189. [Google Scholar]

- Salari, N.; Hosseinian-Far, A.; Jalali, R.; Vaisi-Raygani, A.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Mohammadi, M.; Rasoulpoor, S.; Khaledi-Paveh, B. Prevalence of stress, anxiety, depression among the general population during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Glob. Health 2020, 16, 28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Pan, R.; Wan, X.; Tan, Y.; Xu, L.; Ho, C.S.; Ho, R.C. Immediate psychological responses and associated factors during the initial stage of the 2019 coronavirus disease (COVID-19) epidemic among the general population in China. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 1729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mazza, M.G.; De Lorenzo, R.; Conte, C.; Poletti, S.; Vai, B.; Bollettini, I.; Melloni, E.M.T.; Furlan, R.; Ciceri, F.; Rovere-Querini, P. Anxiety and depression in COVID-19 survivors: Role of inflammatory and clinical predictors. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 89, 594–600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kohler, O.; Krogh, J.; Mors, O.; Eriksen Benros, M. Inflammation in depression and the potential for anti-inflammatory treatment. Curr. Neuropharmacol. 2016, 14, 732–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Varatharaj, A.; Thomas, N.; Ellul, M.A.; Davies, N.W.; Pollak, T.A.; Tenorio, E.L.; Sultan, M.; Easton, A.; Breen, G.; Zandi, M. Neurological and neuropsychiatric complications of COVID-19 in 153 patients: A UK-wide surveillance study. Lancet Psychiatry 2020, 7, 875–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Troyer, E.A.; Kohn, J.N.; Hong, S. Are we facing a crashing wave of neuropsychiatric sequelae of COVID-19? Neuropsychiatric symptoms and potential immunologic mechanisms. Brain Behav. Immun. 2020, 87, 34–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baig, A.M.; Khaleeq, A.; Ali, U.; Syeda, H. Evidence of the COVID-19 virus targeting the CNS: Tissue distribution, host–virus interaction, and proposed neurotropic mechanisms. ACS Chem. Neurosci. 2020, 11, 995–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Soudry, Y.; Lemogne, C.; Malinvaud, D.; Consoli, S.-M.; Bonfils, P. Olfactory system and emotion: Common substrates. Eur. Ann. Otorhinolaryngol. Head Neck Dis. 2011, 128, 18–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Regina, J.; Papadimitriou-Olivgeris, M.; Burger, R.; Le Pogam, M.-A.; Niemi, T.; Filippidis, P.; Tschopp, J.; Desgranges, F.; Viala, B.; Kampouri, E. Epidemiology, risk factors and clinical course of SARS-CoV-2 infected patients in a Swiss university hospital: An observational retrospective study. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0240781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, E.L. Parametric versus nonparametrics: Two alternative methodologies. In Selected Works of EL Lehmann; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2012; pp. 437–445. [Google Scholar]

- Cascella, M.; Di Napoli, R.; Carbone, D.; Cuomo, G.F.; Bimonte, S.; Muzio, M.R. Chemotherapy-related cognitive impairment: Mechanisms, clinical features and research perspectives. Recenti Progress. Med. 2018, 109, 523–530. [Google Scholar]

- Miyake, A.; Friedman, N.P.; Emerson, M.J.; Witzki, A.H.; Howerter, A.; Wager, T.D. The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cogn. Psychol. 2000, 41, 49–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Roussel, M.; Godefroy, O. La batterie GREFEX: Données normatives. In Fonctions Exécutives et Pathologies Neurologiques et Psychiatriques, 1st ed.; de Boeck Superieur: Ottignies, Belgium, 2008; pp. 231–252. [Google Scholar]

- Drozdick, L.W.; Raiford, S.E.; Wahlstrom, D.; Weiss, L.G. The Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale—Fourth Edition and the Wechsler Memory Scale—Fourth Edition. In Contemporary Intellectual Assessment: Theories, Tests, and Issues; Flanagan, D.P., McDonough, E.M., Eds.; The Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kessels, R.P.; Van Zandvoort, M.J.; Postma, A.; Kappelle, L.J.; De Haan, E.H. The Corsi block-tapping task: Standardization and normative data. Appl. Neuropsychol. 2000, 7, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, P.; Fimm, B. Test for Attentional Performance (TAP), Version 2.1, Operating Manual; PsyTest: Herzogenrath, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Grober, E.; Buschke, H. Genuine memory deficits in dementia. Dev. Neuropsychol. 1987, 3, 13–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van der Linden, M.; Coyette, F.; Poitrenaud, J.; Kalafat, M.; Calacis, F.; Wyns, C.; Adam, S. L’épreuve de rappel libre/rappel indicé à 16 items (RL/RI-16). In L’évaluation des Troubles de la Mémoire: Présentation de Quatre Tests de Mémoire Épisodique (Avec Leur Étalonnage); Van der Liden, M., Adam, S., Agniel, A., Baisset Mouly, C., et al., Eds.; Solal: Marseille, France, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Meyers, J.E.; Meyers, K.R. Rey Complex Figure Test and Recognition Trial Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources: Lutz, FL, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Macoir, J.; Gauthier, C.; Jean, C.; Potvin, O. BECLA, a new assessment battery for acquired deficits of language: Normative data from Quebec-French healthy younger and older adults. J. Neurol. Sci. 2016, 361, 220–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahieux-Laurent, F.; Fabre, C.; Galbrun, E.; Dubrulle, A.; Moroni, C.; Sud, G.; Groupe de réflexion sur les praxies du CMRR Île-de-France Sud. Validation d’une batterie brève d’évaluation des praxies gestuelles pour consultation Mémoire. Évaluation chez 419 témoins, 127 patients atteints de troubles cognitifs légers et 320 patients atteints d’une démence. Rev. Neurol. 2009, 165, 560–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrington, E.K.; James, M. The Visual Object and Space Perception Battery; Thames Valley Test Company: Bury St. Edmunds, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler, D. Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (WAIS–IV), 4th ed.; NCS Pearson: San Antonio, TX, USA, 2008; Volume 22, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel, K.; Grandjean, D.; Scherer, K.R. Introducing the Geneva emotion recognition test: An example of Rasch-based test development. Psychol. Assess. 2014, 26, 666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Thomas-Antérion, C.; Ribas, C.; Honoré-Masson, S.; Million, J.; Laurent, B. Evaluation de la plainte cognitive de patients Alzheimer, de sujets MCI, anxiodépressifs et de témoins avec le QPC (Questionnaire de Plainte Cognitive). Neurol. Psychiatr. Gériatrie 2004, 4, 30–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, R.M.; Gioia, G.A.; Isquith, P.K. BRIEF-A: Behavior Rating Inventory of Executive Function—Adult Version; Mapi Research Trust: Lyin, France, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Leicht, H.; Berwig, M.; Gertz, H.-J. Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease: The role of impairment levels in assessment of insight across domains. J. Int. Neuropsychol. Soc. 2010, 16, 463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosen, H.J.; Alcantar, O.; Rothlind, J.; Sturm, V.; Kramer, J.H.; Weiner, M.; Miller, B.L. Neuroanatomical correlates of cognitive self-appraisal in neurodegenerative disease. Neuroimage 2010, 49, 3358–3364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Tondelli, M.; Barbarulo, A.M.; Vinceti, G.; Vincenzi, C.; Chiari, A.; Nichelli, P.F.; Zamboni, G. Neural correlates of Anosognosia in Alzheimer’s disease and mild cognitive impairment: A multi-method assessment. Front. Behav. Neurosci. 2018, 12, 100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Harrison, A.G.; Beal, A.L.; Armstrong, I.T. Predictive value of performance validity testing and symptom validity testing in psychoeducational assessment. Appl. Neuropsychol. 2021; Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar]

- Abeare, K.; Razvi, P.; Sirianni, C.D.; Giromini, L.; Holcomb, M.; Cutler, L.; Kuzmenka, P.; Erdodi, L.A. Introducing alternative validity cutoffs to improve the detection of non-credible symptom report on the BRIEF. Psychol. Inj. Law 2021, 14, 2–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, A.T.; Steer, R.A.; Brown, G.K. Manual for the Beck Depression Inventory-II; Psychological Corporation: San Antonio, TX, USA, 1996; Volume 1, p. 82. [Google Scholar]

- Spielberger, C.D.; Gorsuch, R.L.; Lushene, R.; Vagg, P.R.; Jacobs, G.A. Manuel de L’inventaire D’anxiété État-Trait Forme Y (STAI-Y); Editions du Centre de Psychologie Appliquée: Paris, France, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Ang, Y.-S.; Lockwood, P.; Apps, M.A.; Muhammed, K.; Husain, M. Distinct subtypes of apathy revealed by the apathy motivation index. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0169938. [Google Scholar]

- Ashbaugh, A.R.; Houle-Johnson, S.; Herbert, C.; El-Hage, W.; Brunet, A. Psychometric validation of the English and French versions of the Posttraumatic Stress Disorder Checklist for DSM-5 (PCL-5). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, I.K. Questions & Answers about Depression and Its Treatment: A Consultation with a Leading Psychiatrist; Charles Press Pub: Prague, Czech Republic, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Carlson, E.B.; Putnam, F.W. Dissociative experiences scale. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1986, 4, 174. [Google Scholar]

- Lesage, F.-X.; Berjot, S.; Deschamps, F. Psychometric properties of the French versions of the Perceived Stress Scale. Int. J. Occup. Med. Environ. Health 2012, 25, 178–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gross, J.; John, O. Emotion regulation questionnaire. NeuroImage 2003, 48, 9. [Google Scholar]

- Doherty, R.W. The emotional contagion scale: A measure of individual differences. J. Nonverbal Behav. 1997, 21, 131–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Debouverie, M.; Pittion-Vouyovitch, S.; Louis, S.; Guillemin, F. Validity of a French version of the fatigue impact scale in multiple sclerosis. Mult. Scler. J. 2007, 13, 1026–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morin, C.M. Insomnia: Psychological Assessment and Management; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Johns, M.W. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The Epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep 1991, 14, 540–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kobal, G.; Klimek, L.; Wolfensberger, M.; Gudziol, H.; Temmel, A.; Owen, C.; Seeber, H.; Pauli, E.; Hummel, T. Multicenter investigation of 1036 subjects using a standardized method for the assessment of olfactory function combining tests of odor identification, odor discrimination, and olfactory thresholds. Eur. Arch. Oto-Rhino-Laryngol. 2000, 257, 205–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bousquet, J.; Bullinger, M.; Fayol, C.; Marquis, P.; Valentin, B.; Burtin, B. Assessment of quality of life in patients with perennial allergic rhinitis with the French version of the SF-36 Health Status Questionnaire. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 1994, 94, 182–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frei, A.; Balzer, C.; Gysi, F.; Leros, J.; Plohmann, A.; Steiger, G. Kriterien zur Bestimmung des Schweregrades einer neuropsychologischen Störung sowie Zuordnungen zur Funktions-und Arbeitsfähigkeit. Z. Für Neuropsychol. 2016, 27, 107–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heaton, R.K.; Grant, I.; Matthews, C.G. Comprehensive Norms for an Expanded Halstead-Reitan Battery: Demographic Corrections, Research Findings, and Clinical Applications; Psychological Assessment Resources: Lutz, FL, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, Y.; Wu, J.; Chen, T.; Li, J.; Zhang, G.; Wu, D.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, N.; Cai, A.; Ning, Q. Long-term microstructure and cerebral blood flow changes in patients recovered from COVID-19 without neurological manifestations. J. Clin. Investig. 2021, 131, e147329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Husain, M.; Roiser, J.P. Neuroscience of apathy and anhedonia: A transdiagnostic approach. Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 2018, 19, 470–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCrimmon, R.J.; Ryan, C.M.; Frier, B.M. Diabetes and cognitive dysfunction. Lancet 2012, 379, 2291–2299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spagnolo, P.A.; Manson, J.E.; Joffe, H. Sex and Gender Differences in Health: What the COVID-19 Pandemic Can Teach Us; American College of Physicians: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Schlegel, K.; von Gugelberg, H.M.; Makowski, L.M.; Gubler, D.A.; Troche, S.J. Emotion Recognition Ability as a Predictor of Well-Being During the COVID-19 Pandemic. Soc. Psychol. Personal. Sci. 2021, 12, 1380–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iadecola, C.; Anrather, J.; Kamel, H. Effects of COVID-19 on the nervous system. Cell 2020, 183, 16–27.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fajnzylber, J.; Regan, J.; Coxen, K.; Corry, H.; Wong, C.; Rosenthal, A.; Worrall, D.; Giguel, F.; Piechocka-Trocha, A.; Atyeo, C. SARS-CoV-2 viral load is associated with increased disease severity and mortality. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magleby, R.; Westblade, L.F.; Trzebucki, A.; Simon, M.S.; Rajan, M.; Park, J.; Goyal, P.; Safford, M.M.; Satlin, M.J. Impact of SARS-CoV-2 viral load on risk of intubation and mortality among hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2020, 73, e4197–e4205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heck, D.H.; Kozma, R.; Kay, L.M. The rhythm of memory: How breathing shapes memory function. J. Neurophysiol. 2019, 122, 563–571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lane, R.D. Neural substrates of implicit and explicit emotional processes: A unifying framework for psychosomatic medicine. Psychosom. Med. 2008, 70, 214–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Mild (No Hospitalization) n = 15 | Moderate (Conventional Hospitalization) n = 15 | Severe (ICU Hospitalization) n = 15 | p Value b | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age in years (mean ± SD) (range) | 53.33 (±8.93) (39–65) | 55.87 (±11.45) (38–74) | 61.80 (±10.42) (44–78) | ns |

| Education level in years [level 1 to 3] a (mean ± SD) | 2.67 (±0.49) | 2.53 (±0.74) | 2.40 (±0.63) | ns |

| Gender (F/M) | 8/7 | 9/6 | 2/13 | 0.021 |

| Number of day’s post-discharge (mean ± SD) and (range) | 247.33 (±19.61) (216–282) | 226.53 (±24.85) (195–273) | 236.00 (±20.30) (195–270) | ns |

| Days of hospitalization (mean ± SD) | - | 9.27 (±9.52) | 37.40 (±30.50) | - |

| Diabetes | 0/15 | 2/15 | 5/15 | 0.041 |

| Smoking | 2/15 | 0/15 | 1/15 | ns |

| History of respiratory disorders | 3/15 | 3/15 | 5/15 | ns |

| History of cardiovascular disorders | 3/15 | 2/15 | 4/15 | ns |

| History of neurological disorders | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 | - |

| History of psychiatric disorders | 1/15 | 0/15 | 1/15 | ns |

| History of cancer | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 | - |

| History of severe immunosuppression | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 | - |

| History of developmental disorders | 0/15 | 0/15 | 0/15 | - |

| Chronic renal failure | 0/15 | 0/15 | 2/15 | ns |

| Sleep apnea syndrome | 1/15 | 1/15 | 3/15 | ns |

| Quality-of-Life Domains (SF-36) + | Mild (No Hospitalization) (n = 15) Mean (±SD) | Moderate (Conventional Hospitalization) (n = 15) Mean (±SD) | Severe (ICU Hospitalization) (n = 15) Mean (±SD) | Kruskal–Wallis p Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Overall health | 62.67 (±16.89) | 59.33 (±27.31) | 66.00 (±24.14) | 0.808 |

| Physical function | 80.00 (±17.22) | 82.33 (±19.44) | 77.33 (±24.41) | 0.806 |

| Physical role | 58.33 (±30.86) | 53.33 (±43.16) | 71.67 (±36.43) | 0.353 |

| Emotional role | 64.45 (±36.67) | 73.34 (±36.08) | 80.00 (±37.38) | 0.314 |

| Social function | 57.50 (±23.05) | 66.67 (±31.93) | 85.00 (±18.42) ** | 0.011 |

| Physical pain | 57.83 (±20.81) | 72.00 (±29.40) | 71.83 (±25.61) | 0.153 |

| Emotional well-being | 58.13 (±17.75) | 61.33 (±24.96) | 79.2 (±17.90) **’’ | 0.010 |

| Vitality score | 38.66 (±16.20) | 49.00 (±27.14) | 56.00 (±14.17) ** | 0.039 |

| Health modification | 30.00 (±16.90) | 35.00 (±24.64) | 43.33 (±17.59) | 0.143 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Voruz, P.; Allali, G.; Benzakour, L.; Nuber-Champier, A.; Thomasson, M.; Jacot de Alcântara, I.; Pierce, J.; Lalive, P.H.; Lövblad, K.-O.; Braillard, O.; et al. Long COVID Neuropsychological Deficits after Severe, Moderate, or Mild Infection. Clin. Transl. Neurosci. 2022, 6, 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ctn6020009

Voruz P, Allali G, Benzakour L, Nuber-Champier A, Thomasson M, Jacot de Alcântara I, Pierce J, Lalive PH, Lövblad K-O, Braillard O, et al. Long COVID Neuropsychological Deficits after Severe, Moderate, or Mild Infection. Clinical and Translational Neuroscience. 2022; 6(2):9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ctn6020009

Chicago/Turabian StyleVoruz, Philippe, Gilles Allali, Lamyae Benzakour, Anthony Nuber-Champier, Marine Thomasson, Isabele Jacot de Alcântara, Jordan Pierce, Patrice H. Lalive, Karl-Olof Lövblad, Olivia Braillard, and et al. 2022. "Long COVID Neuropsychological Deficits after Severe, Moderate, or Mild Infection" Clinical and Translational Neuroscience 6, no. 2: 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ctn6020009

APA StyleVoruz, P., Allali, G., Benzakour, L., Nuber-Champier, A., Thomasson, M., Jacot de Alcântara, I., Pierce, J., Lalive, P. H., Lövblad, K.-O., Braillard, O., Coen, M., Serratrice, J., Pugin, J., Ptak, R., Guessous, I., Landis, B. N., Assal, F., & Péron, J. A. (2022). Long COVID Neuropsychological Deficits after Severe, Moderate, or Mild Infection. Clinical and Translational Neuroscience, 6(2), 9. https://doi.org/10.3390/ctn6020009